thirteen

The Prison Cookbook

The idea of a cookery book for prison staff had its roots in the report of the committee inquiring into prison dietaries, published in 1878. In addition to its dietary proposals, the report complained that much food was wasted by unskilful cooking. This was particularly said to be true of meat, which prison kitchens often cooked at too high a temperature, turning it into ‘a condensed shrunken mass of little or no nutritive value’. The use of a thermometer had been suggested as a remedy for this problem.

To try and improve culinary skills, the committee recommended ‘the advisability of forwarding instructions on this important subject to each prison, or of passing the prison cooks through a short course of tuition’.208 In the meantime, it offered a brief list of ‘ingredients and instructions’ for various dishes in the revised dietary:

Bread |

To be made with whole meal, which is to consist of all the products of grinding the wheaten grain, with the exception of the coarser bran. |

Soup |

In every pint 4oz clod (or shoulder), cheek, neck, leg, or shin of beef; 4oz split peas; 2oz fresh vegetables; ½oz onions; pepper and salt. |

Suet Pudding |

1½oz mutton suet, 8oz flour, and about 6½oz water to make 1 pound. |

Gruel |

2oz coarse Scotch oatmeal to the pint, with salt. |

Porridge |

3oz coarse Scotch oatmeal to the pint, with salt. |

Stirabout |

Equal parts of Indian meal and oatmeal, with salt. |

Cocoa |

To every pint, ¾oz flaked or Admiralty cocoa. Sweetening: |

Meat liquor, or broth |

The liquor in which the meat is cooked on Mondays and Fridays is to be thickened with ¼oz flour, and flavoured with ¼oz onions to each ration, with pepper and salt to taste. |

THE MANUAL OF COOKING AND BAKING

The call for a prison recipe book was reiterated by the Departmental Committee conducting the 1898 dietary review. The report also expressed disapproval of the existing method of issuing cooking instructions on loose sheets. Instead, it proposed that a ‘manual of cooking’ similar to that issued for military cooks should be placed in the hands of cooks in the prison service. The result was the Manual of Cooking & Baking for the Use of Prison Officers – published in 1902 and printed at Parkhurst prison.

The Manual, reproduced in its entirety as part of this book, was much more than a list of recipes. It encouraged its readers to understand the scientific principles that underpinned successful food preparation, and to adopt a methodical approach, without which the results would often be ‘unsatisfactory and disappointing’. It thus contained chapters on: the chemistry of food; basic kitchen practice; guidance on the inspection, selection and storage of ingredients; the basics of cooking; prison diets; hospital diets; and – being a prison cookbook – an extensive section on the principles and practice of bread-making. Despite its ‘scientific’ approach, a modern reader will often be surprised by some of the directions, particularly for the cooking times of various items, for example porridge (‘for at least half an hour’), cabbage (‘40 to 45 minutes’), carrots (‘one hour when old’) and cornflour sauce (‘fifteen minutes’). Tea was to be brewed for ‘about 10 minutes’. On the subject of hospital food, the Manual had a fairly liberal interpretation of the official dietary and included recipes for dishes such as veal broth, chicken balls, fishcakes and stewed figs.

Coincidentally, the Manual appeared the year after a similar though unconnected work was published for use by workhouses. 209 Comparison of the two shows how much attitudes towards the workhouse had changed, with inmates there now receiving dishes such as meat pasties, sea pie or hotch-potch stew, with roley-poley pudding, golden pudding or seed cake to follow.

A similar broadening of the prison diet took several decades to materialise. A second edition of the prisons’ Manual appeared in 1935 when, thanks to the work of the 1925 Departmental Committee on Diets, items such as Irish stew, hot pot, shepherd’s pie and treacle pudding had joined the menu.

THE GUIDE FOR COOK AND BAKER OFFICERS

A more comprehensive overhaul of the Manual resulted in the 1949 Guide for Cook and Baker Officers, itself updated in 1958. By this time, the contents of the Guide looked little different from a typical domestic cookery book of the day, except that the quantities specified in its recipes were to serve 100. The making of cocoa, for example, required 4lb 11oz of cocoa, 7 pints milk and 12 gallons water – the cocoa to be boiled in the water for one hour.

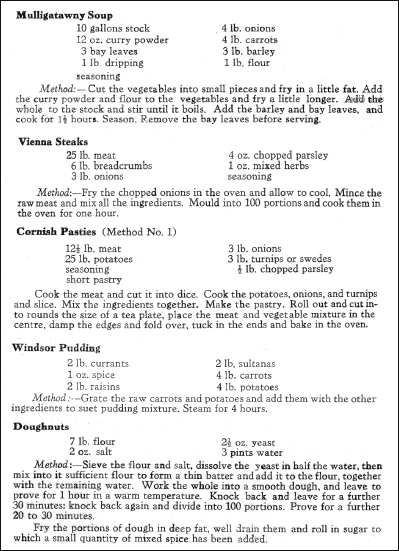

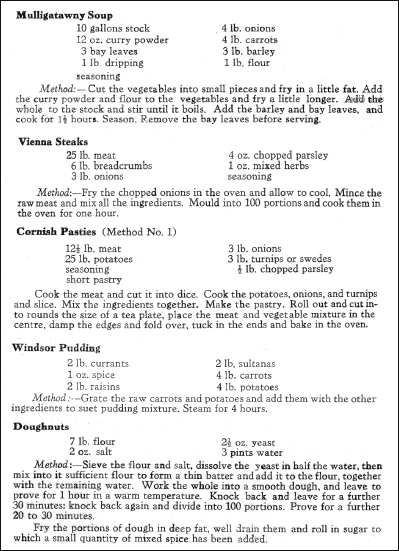

Amongst the innovations was a section on herbs and spices, such as the use of bay leaves for flavouring stews, pickles, prunes and soused herrings; carraway seeds for flavouring cakes and buns; fennel for flavouring sauces – usually served with fish; and mace for minced meat or fish dishes. Potatoes still featured prominently in the Guide, with ten suggested ways of serving them (boiled, baked, fatless roast, croquettes, au gratin, steamed, jacket, mashed, savoury and sauté). Porridge recipes were limited to a mere three – for fine, medium and coarse oatmeal. The range of other dishes had grown enormously and included items such as mulligatawny soup, baked herrings, cottage pie, Cornish pasties, toad in the hole, Vienna steaks, roast pork and stuffing, Windsor pudding, apple turnovers, gingerbread, chocolate sauce and doughnuts.

A selection of the much wider range of recipes on offer in the Guide for Cook and Baker Officers, first issued in 1949.

TRAINING

As well as the production of a cookery book, the 1898 Departmental Committee called for the systematic training of all prison cooks, bakers and millers, and for those involved in the inspection of food supplies. By the time the committee’s report was published, a training scheme had already been set up by the Prison Commissioners. Training courses for prison cooks and bakers were introduced in 1898 as part of a wider initiative to set up ‘training schools’ to be given to all newly appointed prison personnel, including warders, hospital attendants, and clerical staff. The first school of cookery was held at Wormwood Scrubs prison under the supervision of the inspecting and examining chef from the National School of Cookery.210 Following the training courses, it was noted that reports had been received ‘from all quarters as to the improvement that has taken place in the quality of the prison cooking’.211