fourteen

Prisons Enter the Twentieth Century

By the end of the nineteenth century, the prison system had undergone enormous changes. Gaolers no longer lived off fees extracted from their prisoners. The hulks had long gone and transportation had ended. Unproductive labour such as the tread-wheel had been abolished. Some well-known prisons had disappeared – the Marshalsea closed in 1842, Millbank was demolished in 1890 and Newgate was to go the same way in 1902. New prisons, still in use today, had taken their place, including Parkhurst (opened in 1838), Pentonville (1842), Dartmoor (1850), Wandsworth (1851), Holloway (1852), Brixton (1853) and Wormwood Scrubs (1883). In 1818 there had been 338 prisons in England and Wales.212 By 1900, only sixty-one prisons remained – fifty-six local and five convict – although the total capacity remained virtually unchanged at around 24,000 inmates. 213

Despite this dramatic reduction in prison establishments, the number of those serving prison sentences had actually risen. In 1818, about 107,030 persons had been put in prison, while in the year up to March 1901, 148,600 were sent by the ordinary courts to local prisons, with a further 12,576 imprisoned as debtors. In the same period, convict prisons received 797 new inmates, and 785 convicts were placed in local prisons. However, the rise in prison sentences was much smaller than the growth in the overall population (from 11.8 million in 1818 to 32.6 million in 1900). Most of those in local prisons were now serving very short sentences – an average of thirty-six days, with many being inside for two weeks or less. Very few sentences were longer than three months. 214

Some of those most affected by the changes in the penal system were young offenders. In addition to the existing reformatories and industrial schools for those under 16, the Gladstone Committee had proposed that a special institution be set up to deal with offenders aged from 16 to 21. An experimental scheme was set up at Bedford in 1899, and then extended in 1901 using part of the convict prison at Borstal in Kent. The young inmates were kept apart from the adult prisoners and given a routine which included physical exercise, school lessons, work training, strict discipline and follow-up supervision after their discharge. The formal adoption of the Borstal system came in the 1908 Prevention of Crime Act. A second borstal institution was established at Feltham in 1910 (in the premises of the former Middlesex Industrial School), and another at Portland in 1921, with one for girls being set up at Aylesbury prison in 1909. Some existing prisons implemented a ‘modified borstal’ system, providing accommodation and treatment for those serving short sentences.

Changes were taking place for other groups too. There were moves to concentrate female prisoners in a small number of dedicated institutions. Holloway became an all-women’s prison in 1902, while outside London prisons such as Liverpool began to develop in this role. Following the 1898 Inebriates Act, a number of special inebriate reformatories were set up for ‘habitual drunkards’ who committed offences while under the influence of alcohol. Some of these were operated by the National Institutions for Inebriates, a charity run by clergyman and former missionary the Rev. Harold Burden, which took over former workhouses for the purpose at Lewes in Sussex and at Guiltcross in Norfolk.

For those convicted of the most serious crimes, such as murder, hanging remained the ultimate sanction until its abolition in 1965. However, the use of the death penalty was already in dramatic decline. Those sentenced to death in 1818 numbered 1,254 of which ninety-seven were actually executed.215 In 1900, only twenty received the death penalty, with around three quarters of those actually facing the hangman. The spectacle of public executions ended in 1868 and now took place behind closed doors. From 1908, the minimum age for execution was raised to 16.

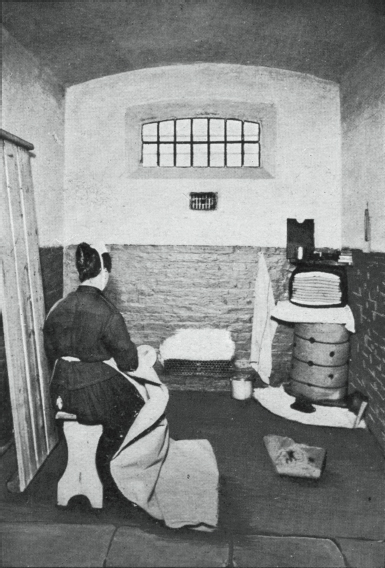

A women’s prison cell at Holloway prison in 1901. The occupant is engaged in sack-making. Her plank bed can be seen standing on end at the left. From 1902, all London’s female prisoners were held at Holloway.

The 1901 scene outside Holloway where relatives or friends wait to meet those being discharged from the prison.

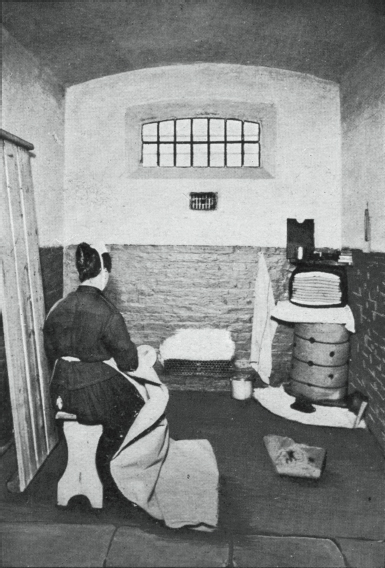

An aerial view of London’s Wormwood Scrubs, opened as a convict prison in 1883 then used as a local prison from 1890. It used a ‘telegraph-pole’ layout, a design which had been popularised in the pavilion plan hospitals of the period promoted by Florence Nightingale. The cell blocks, linked by covered passageways, ran north–south to receive sunlight at each side during the day.

Internally, the Wormwood Scrubs cell blocks resembled the galleried wings of older prisons. This view, from around 1900, shows prisoners returning to their cells for dinner.

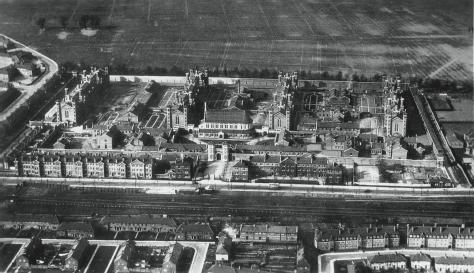

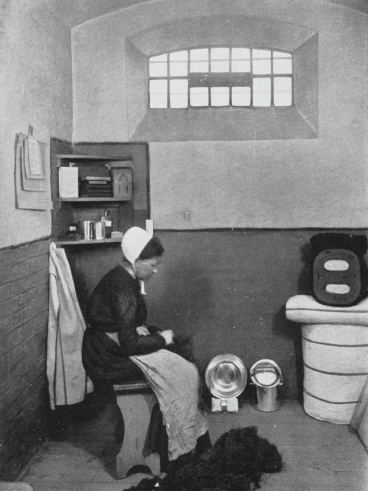

A women’s cell at Wormwood Scrubs in 1896 with bedding stowed away at the right. The corner shelves contain a few books from the prison library. The prisoner is picking oakum – teasing apart old rope into its raw strands.

The ‘babies’ parade’ – female prisoners with their infants taking outdoor exercise at Wormwood Scrubs in 1896. Nurseries for such children were established in a number of prisons in the nineteenth century.

An early version of the ‘Black Maria’ used to carry prisoners to and from gaol. The prisoners were placed in cells at each side of the vehicle and were accompanied during their journey by a constable.

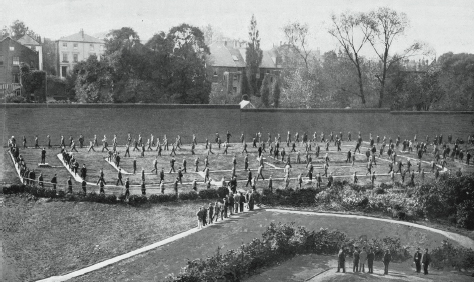

Male prisoners taking a turn around the exercise yard at Holloway in 1901 – their perambulations apparently proving something of a spectator sport. When the prison became women-only in the following year the men were moved to Brixton, originally opened in 1853 as a convict prison, but which had served as a military prison since 1882.

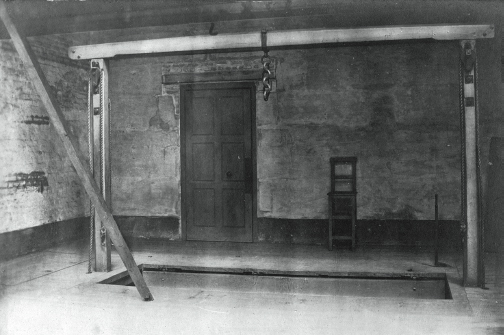

The interior of Newgate’s execution shed. Local prisons could requisition a ten-piece hanging ‘kit’ from Holloway or Pentonville. It comprised a rope, a pinioning apparatus, a cap, a bag holding sand to the weight of the prisoner in his clothes, a piece of chalk, a few feet of copper wire, a six-foot graduated pole, pack-thread just strong enough to support the rope without breaking, a tackle to raise the bag of sand or the body out of the pit, and a chain with a shackle and pin. And, presumably, some instructions.

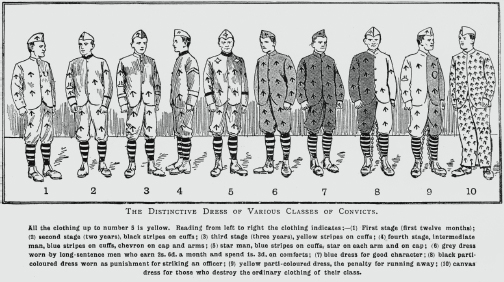

A comparison of the ten different styles of convict uniforms in use in around 1900. The arrow motif was also included in studs on the underside of the men’s boots.

DEVELOPMENTS AFTER 1920

In the first four decades of the twentieth century, the prison population dropped from a daily average of just under 15,000 in 1901 to just over 10,000 immediately prior to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.216 As a result, there was virtually no new prison building.

Things were not standing still inside the prison system, however. Reforms during the 1920s and 1930s began to make prisons much more humane places. From 1921, the ‘convict crop’ haircut was abolished, together with the broad arrows on prison uniforms; transfers between prisons were now in civilian clothes; prisoners could have a shave before attending court; the bars or wires separating inmates from their visitors were removed and replaced by an ordinary table; there were relaxations in the rules preventing talking between prisoners.217 Compulsory chapel attendance was abolished in 1924, and the month-long initial solitary confinement of new prisoners ended in 1931. Other changes in this period included the introduction of educational courses run by voluntary teachers, film shows, lectures, amateur dramatics and radio sets. An earnings scheme introduced in 1933 allowed inmates to buy goods from prison canteens.218

A significant trend in prison accommodation began in 1930 with the opening of a new ‘open’ Borstal at Lowdham Grange, near Nottingham. A group of forty boys marched the 132 miles there from Feltham, initially living in tents and huts while they built their own institution, which lacked the usual walls or barbed wire perimeter. In 1934, the first open prison for adults was established at New Hall Camp, near Wakefield. During the day, inmates at open prisons were able to work in the open air on a farm or outside at local factories. For juvenile offenders, 1932 brought an end to reformatories and industrial schools and their replacement by a single system of approved schools.

Young offenders doing farm work at Lowdham Grange borstal in the 1940s. The borstal was largely self-sufficient in items such as milk, eggs and vegetables.

A major shake-up of the prison system came soon after the Second World War in the shape of the 1948 Criminal Justice Act which, amongst other things, abolished penal servitude, hard labour and whipping. The Act also introduced a new sentence of corrective training for younger offenders and established two new types of institution – the detention centre (providing a ‘short sharp shock’ for first offenders between 14 and 21) and the remand centre (for those awaiting trial or sentence).

At Norwich prison, an experiment began in 1956 where prison warders were encouraged to get to know their prisoners on a more personal level. This was accompanied by a move towards dining in association for all convicted prisoners and an increase in the time spent out of cells at work. The so-called ‘Norwich system’ achieved beneficial results for both staff and inmates and its use was taken up by other local prisons.

THE GROWING PRISON POPULATION

An increase in crime rates in the years following the Second World War eventually resulted in a major programme of new prison construction with Everthorpe, in 1958, being the first new closed prison to be built since Victorian times. Following the publication in 1959 of an influential parliamentary White Paper Penal Practice in a Changing Society, around forty new penal establishments were opened. ‘New Wave’ prisons, such as Blundeston, Coldingley and Long Lartin, employed a novel style of design based on the principle that cells were used only as bedrooms and so omitted built-in WCs or space for eating. Instead of the galleried radial wings of Victorian prisons, the new buildings generally consisted of several T-shaped blocks clustered around a central service building which contained classrooms, library, canteen, kitchens, gymnasium and chapel. 219

After the 1960s, construction of new prisons steadily continued and experiments were made with a wide range of designs. The mid-1980s saw the influence of ‘new generation’ ideas from the USA, where small groups of inmates were housed in small triangular house blocks organised around a central communal area. At the opposite end of the spectrum, new prison buildings at Woolwich, Bicester and Bullingdon saw a return to the use of galleried wings reminiscent of Victorian prisons.220

Many new buildings during this period were for young offenders, supporting the aim of keeping them out of prison. Those receiving sentences of up to six months were to be placed in detention centres, with borstal training for those serving up to three years. Borstals were rebranded as Youth Custody Centres in 1983 then from 1988 became known as Young Offenders Institutions, after merging with the former youth detention centres which were abolished as a separate form of establishment.

As well as the erection of new buildings, there was a programme of refurbishment and reconstruction of old prisons. The most extensive project was at Holloway women’s prison where, between 1970 and 1983, the Victorian buildings were completely replaced at a final cost of £40 million – more than six times the original estimate. The new layout was made up of a number of small separate cell blocks, linked by a corridor, and arranged around a ‘village green’, with communal facilities such as workshops, a swimming pool and chapel. However, its sprawling layout was subsequently criticised as being hard to supervise and control.221

Despite efforts to expand prison accommodation, it struggled to keep up with the growth in the prison population, which rose from just over 20,000 in 1950 to over 83,000 by 2009. Overcrowding was a regular feature of many prisons – in 1981, almost 5,000 prisoners were living three to a cell, in a space originally designed for one. Triple-sharing was abolished in 1994, although this was only achieved by an increase in the numbers of prisoners sharing with one other. Overcrowding has become markedly worse in recent times with prison numbers increasing by 85 per cent since 1993. In 2006, the UK government announced ‘Operation Safeguard’ – a contingency plan for situations where the shortage of prison places becomes acute. Under the scheme, temporary holding cells at police stations are pressed into use as additional prison accommodation. At the end of 2007, the government announced plans for three new 2,500-capacity ‘super-prisons’ as part of measures to create 10,500 new prison places. On 22 February 2008, the accommodation crisis finally reached breaking point when, for the first time ever, the total population exceeded the prison system’s useable operational capacity.222 In April 2009, following widespread criticism of the super-prison proposal, the Home Secretary announced a revised plan to erect five smaller prisons, each with a capacity of 1,500 – about the size of the country’s large existing jail at Wandsworth.