California! It was a continent away, but I talked the matter over with Terri, and we hit on a scheme to get me there for next to nothing—precisely my capital holdings. We were active members of YPSL, and the organization was having its annual conference in Chicago. We could get elected as delegates and get a lift that far with whichever other delegate had a car. From there, Gary Craig, a political accomplice from Seattle, planned to get one of those “Triple-A Drive-away” deals, where you got paid gas and expenses for driving somebody’s car from point A to point B, point B in this case being San Francisco. I would join him for that leg of the journey, then Gary would proceed north to Seattle and I south, by hook or by crook, to Hermosa Beach.

I remember almost nothing of the drive to Chicago. There were six of us in a VW Beetle, and I recall dreaming wistfully of the roomy semi cabs and sleek bourgeois bombs I had traveled in when I made that same trip hitchhiking. Hitching cross-country in winter, however, was out of the question; people literally froze to death on the road out there in the wide-open spaces.

The conference was the usual stew of bellow-and-drang and clumsy Machiavellianism to be found wherever young ideologues gather. I loved that stuff, and had a fine time. We stayed at a comrade’s apartment, which Terri later described as having “polka-dot wallpaper that moved”—even as a cockroach connoisseur and veteran of countless East Side crash pads, I had to admit it was pretty impressive. Two other things that I remember: I heard Howlin’ Wolf for the first time, and Gary and I acquired a passenger, A.K. Trevelyan, age twelve, known forever after (by me) as “Red Chief.”

I do not recollect exactly how we got A.K. for a road buddy, but he was the son and heir of an old friend who was sending him to spend some time with his mother in the Bay Area. I did not envy the poor woman. Red Chief had the intellect of an Einstein and the temperament of a pissed-off wolverine.

The arrangement Gary had with Triple-A gave us only four days to get the car to San Francisco. That meant doing about five hundred miles a day, a solid pace but not unreasonable if the roads were clear. Gas money and a small per diem were thrown in, which made a big difference since Gary and I had only about a hundred bucks between us. A.K. had some bread, as well, but he categorically refused to tell us how much.

We left Chicago early in the morning to get as much daylight driving as possible. Gary had to do all of it—I did not have a license, then or ever. The weather got right down to business as soon as we got into Iowa: a regular “blue norther,” snow so thick you had to squint to see your windshield wipers, shrieking winds, the works. There was not another car in sight. We crawled along at 20 miles an hour, losing the road from time to time since the terrain was flat as a pancake and there were no tire tracks to follow. When this would happen, I would get out of the car with a tire iron, poke a hole in the snow, and if I hit dirt we would back up and repeat the procedure until I struck pavement. Clearly, this was not a good system for getting to Omaha by early evening. “Gary,” I said, “if this keeps up, we’ll be lucky if we can reach the next town. We’d better find ourselves a motel and hole up until this blows over.”

“We can’t afford it,” he said. “We only have enough money for three nights of motel.”

“It’s warm in Nevada,” I said. (I was thinking of Las Vegas, not Reno, which was where we were headed, and which gets as cold as the ninth circle.) “When we get there, we can sleep one night in the car. Or else,” I continued, “we could always stay right where we are until they dig us out, sometime in April. That wouldn’t cost a cent.”

Red Chief was in favor of pushing on. He was having the time of his life. Gary was having no fun at all, but he kept driving until somewhere west of Iowa City, at which point my fatuous reasoning, with a strong assist from the blizzard, prevailed. Next morning, bright and early, we were back on the road. In the brilliant sunlight, the world was a vast, flat, blinding snow-field from horizon to horizon. The roads had been sanded, though, and we could do fifty or better—Gary was a superb driver.

The car was a Chevy Impala, which was a pretty hot little number, and we were just waiting to get some dry road under us so we could really boogie. We stopped somewhere around Omaha, but only for gas and a bite to eat. I was beginning what would become a lifelong fascination with “real American chow.” Heretofore, my idea of a Lucullan feast was the kasha varnishkes with mushroom gravy at the Garden Cafeteria on East Broadway, lo mein at Sam Wo’s, or the arroz con pollo the Spanish anarchists used to dish up at their loft on Broadway and 12th. Chicken fried steak? You’ve got to be kidding. Country ham with biscuits and redeye gravy? Hush puppies? Give me a break. Mostly it was awful, but I gradually realized the problem was not the dishes themselves but the fact that the hash slingers in those truck stops were unbelievably lousy cooks. I have since had chicken fried steaks that could stand toe-to-toe with the best filetto di manzo I have ever eaten in Italy.

Whatever may have been wrong with the food, they gave you plenty of it and it was cheap. Gary was a westerner and knew from this stuff, and curiosity led me to experiment. A.K. made faces at it and stuck to BLTs. He was also beginning to develop a parody of a midwestern accent that dripped venom. He would try it out on everybody we talked to, and I was sure it was only a question of time before some no-neck behemoth took offense and killed all three of us on the spot. He especially loved to say “You betcha!” which he seemed to think was the most hilarious thing he had ever heard in his life. We were getting some pretty funny looks.

Our beards did not help a whole lot. The culture wars of the sixties had not yet begun, but the battle lines were forming and one of the great, burning issues was to be “the beard.” You could see it coming—“Hey feller, what’s that growing on your chin? Spinach? Hee, hee, hee.” You smiled politely and disengaged as quickly as possible.

The road opened up in Nebraska; snowbanks six feet high along the shoulders, but the blacktop was clear and dry. Gary was determined to make up lost time, and dropped the hammer. Seventy-five, eighty miles an hour—we were really rolling. Just after dark, we hit a patch of black ice that was slick as greased glass. The car pinwheeled, executing two or three complete spins while we watched helplessly. Somehow Gary managed to get some control, and miraculously brought us to a stop almost gently, against a snowdrift on the side of the road. A quick check of body parts turned up nothing broken, but we were firmly wedged into that snow bank, with our front end three feet deep and nothing but ice under our rear wheels. Gary tried his best, but could not move the damn thing an inch.

So there we sat. Every now and then we would hear a car approaching, and we would pile out, flagging wildly. A couple of guys actually stopped, but lacking tow chains there was nothing they could do. Salvation finally appeared in the form of a local farmer in a pickup with studded tires. “You boys’ve got yourselves in a pickle, fer sher!”

“Yew betcha!” said Red Chief.

Our Good Sam matter-of-factly produced a tow chain, and quick as it takes to tell, we were on dry land again. Time pressure was weighing heavily on us now, so we had to turn down his offer of supper and beds for the night, and directly were tooling down the road again, doing eighty-five. (Incidentally, further research has confirmed that if you must have a disaster, have it happen in the Midwest. Whatever their cultural quirks, those folks can be really nice.)

Night driving in that part of the world is an entirely different thing from what I was used to. Back east there is always some kind of man-made light: a house with a colicky baby, a neon sign, the horizon glow of a distant town, something. But here, out beyond the power lines, especially when the sky is overcast, there is a surreal quality, an isolation that at once numbs the mind and fills it with a vague sense of apprehension.

We raced across the Nebraska plains, preceded by our little cowcatcher of light, in a kind of hypnotic trance. Occasionally, the lights of an oncoming truck would appear, brights clicking on, off, on, off: “Cop ahead,” “Shitty coffee up the line,” or just “Hello, are you alive?” Truckers’ signals. I used to be able to read them, but they have pretty much died out now that all the drivers have radios, and I have long since forgotten.

Maybe we were too spaced-out to notice, or maybe the son of a bitch just materialized like a phantom trooper in a Stephen King novel, but the next thing we knew we were being pulled over by Dudley Do-right. The usual routine: high-powered flashlight in the eyes; license, registration; “Do you know how fast you were going?” The fine, he informed us, was based on the number of miles per hour over the speed limit the culprit was clocked at, and since we had been caught red-handed doing 600 miles per hour, we owed the people of Ignominee County $60. At least that was the gist of it. Then he produced a new wrinkle: since court was closed for the night, we could either go with him into town and wait—in jail, naturally—until it convened, which would be two full days since tomorrow was Saturday, or we could waive the hearing and pay the fine on the spot. Just to guarantee that there was no hanky-panky involved, he would watch while we placed the cash in an envelope, addressed it appropriately, and dropped it into a mail slot at the courthouse. This had all the earmarks of a well-oiled scam, but what could we do? We drove into town with him close behind and stopped in front of City Hall, where with the cop watching, A.K. dug an envelope out of his Boy Scout knapsack and I stuffed the sixty bucks (almost all we had) into it, addressed it, and dispatched it as ordered. A galling and nerve-wracking experience.

Over shitty coffee in an all-night truck stop up the line, we reviewed our position. Gary and I had about $30 between us, there was another $30 or so of gas money from Triple-A, and that was it. Red Chief had some money, but still refused to say how much, and announced that he would pool it with us “over my dead body.” (To myself I muttered, “Ah yes, the scenic route.”) It was a dilemma: we were pressed for time, and if we proceeded legally and sedately at the speed limit, it would take us forever to get out of Nebraska; but if we continued tearing up the pea patch, we ran the risk of having the same rip-off pulled on us again, and that would leave us too broke to continue, sedately or otherwise.

“I say, give ’em the old ‘bait and switch,’” said A.K. with a conspiratorial smirk.

“The old what and which?”

“Here,” he said, “let me show you.” He delved into his knapsack and fished out a box of stationery, did a bit of scrawling on a sheet of letter paper, and before folding it into an envelope, let us take a look. It read, “Deed to the Brooklyn Bridge”—I think he even signed it, “Peter Minuit.” He addressed the envelope to “Town Clowns—Fishfart, Neb.,” and handed it to me. “If we get stopped again and they try that same routine on us, all you have to do is switch envelopes at the last minute.”

“Oh, is that all? And what’s the cop supposed to be doing while I’m prestidigitating? The last one was watching me like a hawk.”

“Don’t worry,” he said. “I’ll think of something.” How a twelve-year-old could come up with a scheme so devious and baroque filled my heart with wonder, but he explained: “Oh, I got it out of a kid’s book.” It is the only time I have heard the Newgate Calendar described as a “kid’s book.”

In any case, what were the odds on getting popped the same way twice in one night? Lightning doesn’t strike etc., etc. Well, just ask any lightning rod about that old saw. Sure enough, not far from the Wyoming line, it happened again. It was still dark. Different cop, but exactly the same routine. As we drove, hangdog, into town, Red Chief said, “When you get out of the car, leave the door open. I’ll divert him.” What the hell was he going to do, throw a brick at the guy? He giggled, and would say no more.

As I trudged, scared shitless, toward the municipal building, one envelope in my hand, the other in my pocket, I suddenly heard a piercing yell: “Hey! Shut that door, I’m freezing to death back here!” The kid had lungs of steel, and I don’t know about that cop, but it sure diverted the hell out of me. I was so startled that I almost botched the substitution, but the thing came off without a hitch. We laughed hysterically all the way to Wyoming.

I guess we must have stopped for gas and even had some breakfast, but other than that we drove straight on through the night. We were rolling merrily along, some fifteen miles east of Cheyenne on a sunny Saturday morning, when we blew a gasket. The Chevy was still ambulatory, but just barely. Gary howled obscenities as we limped down the road at five or ten miles an hour, looking for an open repair shop. At that speed, it took us a while to get into town, where we finally spotted one. “Yep,” the fellow agreed that it was a head gasket. “Nope,” he couldn’t fix it today. The garage closed at noon on Saturday, and it was almost eleven o’clock. The best he could do would be to have it ready early on Monday. Gary explained that Triple-A would be footing the bill, and showed him some papers that seemed to satisfy him. We walked the rest of the way into the center of town.

“First,” said Gary, “we get a cheap room. Then a call to Triple-A for some money, and then some sleep.” The sleep part sounded especially good. We had been going for at least 24 hours and were walking around in a cocoon of daze.

Cheyenne was the state capital, but first and foremost it was a cow town. Ranch hands, who worked half days on Saturday, crowded the sidewalks looking for ways to spend their week’s pay. The atmosphere was festive, although almost nobody was drunk yet.

So we’re walking along, taking it all in, when up steps the Marlboro Man and says (I swear to God), “You boys new in town?” With one hand he flipped open a wallet and flashed a badge, and with the other he produced a cannon that looked to me like Big Bertha. We were so surprised, and so zonked with fatigue, that we could only stand and stare: was this joker for real? All too real, as it turned out. In seconds he had Gary and me handcuffed together, and A.K. cuffed to his left wrist. “I think we’d better go down to the station and have a little talk.” He kept Gary and me in front of him, with A.K. at his side, and he kept that damned bazooka pointed right at us all the time. That hombre didn’t take no chances.

It must have been quite a sight: there we were at high noon, being marched at gunpoint down the main street of Cheyenne, Wyoming, by Wyatt Earp. The locals were enjoying it immensely. They gasped with delight and craned their necks, probably looking for the movie cameras. Nor did they remain silent onlookers: “Hey Bud, looks like you finally caught up with the Dalton boys! Hee, hee, hee.” I must confess, the carnival atmosphere was lost on me at the time, but Red Chief got right into the spirit. He kept looking up at our grim-faced captor and asking, “Air yew the fastest gun in Cheyenne, Shairroff?” I could tell this was going over real big.

At the cop shop, they separated us and grilled us one at a time, with no hint of what the hell it was they were after. Over and over: “What’s your name? Where do you come from? What are you doing here?” and “Who’s the kid?” I kept explaining to them: “His father is a friend of mine. We’re giving him a lift to his mother’s place in San Francisco.” I had his pop’s number with me, and they let me try calling him. No answer.

After the third round of questioning, everybody was getting pretty exasperated, and they started to slap me around a little, on general principles, just to let me know they weren’t too happy with the way things were going. It was looking like things could get very nasty indeed. They let me try the phone again, and—Praise God!—A.K.’s father was home. “Bert,” I said, “we’ve got a bit of a problem here.” I ran down the story for him, and one of the cops got on the line. After some palaver he hung up and said, “We’ve got to check on this. Wait here.” I had a lot of choice. Twenty minutes later he was back: “OK, you can go. Your friends are waiting outside.”

“Just like that?” I said. “Wait a minute. What was this all about?”

He looked a little embarrassed. “We kind of thought you two might have kidnapped the boy.”

I started to laugh. “Why didn’t you ask him?”

“We did,” he answered, “but he wouldn’t tell us a thing.”

“But his I.D. must have checked out.”

“Yeah, it did, but it said he was from New York, and he talked like a shit kicker from Iowa. Now get out of here. It’s coming on Saturday night, and we’re gonna need all the jail cells we’ve got.”

Out on the street, I confronted the little swine: “Why didn’t you just tell them the truth?” I screamed.

All of a sudden he was Humphrey Bogart: “I don’t talk to cops.”

Post mortem in a ratty railroad hotel. Dave: “They hit me a couple of times—nothing serious.”

Gary: “That big bastard with the Stetson kicked me in the shins with those pointy-toed cowboy boots.” He raised his pants leg, and displayed a bruise that was beginning to look like a Turner sunset.

A.K.: “Yeah, they brought me a cold cheeseburger.”

Killing the weekend on a shoestring was no problem at all: We slept. Cheap eats were easy to come by, as well. I continued my culinary research with a substance called “son-of-a-bitch stew” (“S.O.B. Stew” on the lunchroom’s “Daily Specials” blackboard), made from beef unmentionables and seasoned with nasty little bird’s-eye chilies. Good, though.

Monday morning, refinanced by Triple-A by way of Western Union, we picked up the car and were tooling down Route 80 singing—what else?—“Goodbye, Old Paint, I’m Leavin’ Cheyenne.”

That stretch of highway across the high plains of Wyoming can be a traveler’s graveyard in the winter, but this trip it was like a superfast conveyor belt. Gary had previous experience with the route, though, and wanted to get over into Utah and the Great Basin before the shit hit the fan, which at this time of year was almost inevitable. Hitchhikers were few and far between—hell, people were in short supply, period—so when we saw a guy standing on the road with his thumb out, I was usually inclined to give the poor soul a lift. Gary, on the other hand, was really in the slot now and did not want to stop for anything. But this time was different: “Gary!” I yelled, “Stop the car! That guy has a beard!!” He hit the brakes, and it was a lucky thing the road was dry—we must have been doing ninety. We backed up for what seemed like ten miles, and met the guy partway as he trotted to meet us.

Now, the beard factor had been an ongoing irritant in our dealings with the natives since we had left Chicago. Almost every stop we made, there would be comments about our facial hair, and once or twice, only our hasty departure had averted mayhem. Cops seemed especially hostile; both of the times we had been stopped in Nebraska, we had to grin and bear it while Ol’ Smokey trotted out his nimble wit at our expense, and remarks dropped at the station house in Cheyenne suggested pretty strongly that we would not have been collared had we been clean shaven. So it was a question of solidarity. There was no way we were going to leave that poor bastard out there to face the tender mercies of the aborigines.

As it turned out, the poor bastard was an aborigine, and an honest-to-God cowboy to boot. Andrew (“not Andy, goddammit”) could rope (“some”), ride (“pretty good”), and bulldog the kiyoodles (“huh?”) with the best of them. But mostly he wanted to get the hell out of Wyoming. The problem was his beard. He was not trying to make any kind of statement, but had grown it on a whim, and when it came in full, he kind of liked the way it looked—understandable, as it was a fine specimen of what I believe is called a “scup,” full around the edges, with no mustache, as worn by Horace Greeley and Abraham Lincoln. Indeed, Andrew was a handsome specimen entirely. Of medium height, and older than us (about thirty), with his battered Stetson and slightly weather-beaten look, he was the very image of that film director’s dream, “The Last American Cowboy”—and he knew it.

Apparently the scheme had been percolating in his mind for a while, and the beard had finally kicked off a hegira to the coast to get into the movies. His buddies on the ranch where he worked were giving him no peace, calling him “Abe” (in reference to Lincoln, I suppose, but with anti-Semitic undertones), and perfect strangers were always trying to start fights.

“Yeah, tell us about it.”

“So I figured, if I’m gonna look like an extra in Shane, I might as well get paid for it.” I had heard tell of Will Geer’s theater in Topanga Canyon, where Woody Guthrie used to crash and where, according to the grapevine, Jack Elliott was currently holing up, so I passed the word along; maybe a connection with the film colony could be made from there. He liked the sound of that. Comfortably ensconced with a bunch of fellow outcasts, he settled into the backseat with A.K. and began teaching him “real cowboy songs.” As I recall, one of them went:

I am an old cow-puncher; I punch them cows real hard.

I’ve got me a cow-punching bag at home in my back yard.

It’s all made out of leather; it’s real cowhide of course.

When I get tired of punching cows, I go and punch a horse.

Our virtuous deed did not go unrewarded: Andrew had a driver’s license and was only too happy to spell Gary at the wheel. Of course, the insurance on the car would not cover him as a driver, but the clock was still ticking and money was still mighty scarce. Gary proposed that he and Andrew take turns, eight hours on and eight off, driving and sleeping, all the way to San Fran. I thought this really sucked the big one; the idea of sitting in that car for eighteen hours—give or take a couple—made me sick with dread. For a change, A.K. agreed with me. He wanted to have a look at Salt Lake City and do some “real gambling” in Reno. “OK,” Gary told him, “you pick up the motel bills. Besides,” he added spitefully, “they’re not gonna let you gamble in Reno; you’re only a kid.” That actually shut him up for a while. (Red Chief had never been Mr. Popularity with us, and after the “High Noon in Cheyenne” caper, Gary and I tacitly agreed that the more sequestered we kept the kid, the safer we all would be. Personally, if there had been room I would have stowed the little rodent in the trunk.)

With Red Chief silenced—there was no way he would agree to pay the motel—I was outvoted. I glumly resigned myself to an eternity of cramps and claustrophobia and let the matter drop.

West toward the Utah line, Route 80 rises with the terrain into the Wasatch Range—not exactly the Himalayas, but formidable enough—and very scenic, weather permitting. Weather did not permit. As soon as we began to climb, the snow began to fall, and with predictable synchronicity, the higher we climbed, the harder it fell. I am not sure how it happened—maybe the interstate had not yet been completed through the mountains, or maybe some half-wit (probably me, since I was the expedition’s navigator) spotted a shortcut on the road map—but the next thing we knew, we were on a narrow two-lane road in the middle of the mountains, up to our asses in snow. Those were seven or eight of the hairiest, scariest hours I have ever lived through. No question of finding a nice motel and waiting out the storm; there was nothing out there but mountains and chasms with five-hundred-foot drops, and that pathetically narrow road, snaking and hair-pinning around them. We were doing fifteen miles an hour. Once in a rare while, some idiot would actually pass us, raising the tension in the car even higher. Some stretches of that route could not have had more than a few inches of clearance, but the trucks went barreling on through. Did those lunatics want to die? No one had spoken for hours, and I was on the point of screaming, or praying, or just gibbering like an idiot, when the road finally leveled and straightened, the snow tapered off and stopped, and we were out of it.

We slept that night in a motel, and did not even try to make A.K. foot the bill.

Salt Lake City I recall only as an oblong blur. (Rosalie Sorrels, who was living there before she took to the road as a folksinger, assures me that this is a fairly accurate description.) We zipped across the Bonneville Flats and the Great Salt Desert, on over into Nevada, where, mirabile dictu, there was no speed limit.

Gary had been living for this moment. Our handy-dandy road atlas had a chart listing the speed limits of the various states. Next to Nevada it said only “Reasonable and proper.” It was cold out there, and there was snow off the road, but the asphalt itself was straight, flat, and bone-dry. “Hoo boy, lets boogie!” And boogie we did. That Impala was a sweet little item, and Gary put his foot through the floor and got her up to 120. “Gary,” I said, the voice of sweet reason and propriety, “don’t you think a hundred will do?” He grumbled a little, but moderation prevailed and we scooted on past Elko at a stately 100 miles per hour. Splat! A lump of reddish-gray goop appeared on the windshield. “What the fuck was that?” Gary yelled.

“It’s a bird,” said Andrew.

“Yeah sure. It’s a plane, it’s Superman.”

“No, really,” Andrew explained. “The road gets hot from the sun and they stand on it to get warm.”

Sure enough, there were flocks of them now. At our approach, they would take off, but we were moving too fast for all of them to get out of the way. Splat! Splat! It was getting hard to see the road. “Fuck ’em,” Gary grunted through clenched teeth. “We’ve gotta make time! When it gets too bad, we’ll scrape ’em off.” Splat.

“We” turned out to be me. Gary was the driver; Andrew was a guest of sorts; and Red Chief refused, point blank: “Oh no you don’t! Slow down, and you’ll stop hitting them. I’m in no hurry.” So from time to time we would pull over to the side of the road, and I would trundle out, ice scraper in hand, to peel ten pounds of bird porridge off the windshield. Everybody else in the car seemed to think this a perfect division of labor. Be that as it may, we were in Reno in five hours.

In Reno, a mere five more hours short of San Francisco and blessed surcease, the word came down: Route 80 over the Donner Pass was closed to vehicles without tire chains. This was the last straw. We were just about broke again, since the unscheduled stop in Salt Lake had used up our motel money. We could just barely afford some gas and a bite to eat, and that was it. Of course, Gary could phone Triple-A again and ask them to wire us the money to buy a set of chains—it was certainly a legitimate expense—but the money would not get to us until tomorrow, and in the meantime where would we sleep? Gary and I looked pointedly at Red Chief, who we knew still had some cash reserves. “We can sleep in the car,” he quoted, with a big evil smile. “It’s warm in Nevada.” I did not kill him.

I suppose I should admit that, while A.K. was something of a skinflint, he was no freeloader. When a collective expenditure was necessary, he ponied up like a mensch. If worst had come to worst, he would probably have shelled out for a cheap room in a squalid motor court—I think. But at least to my sleep-deprived mind, it seemed as if there was another way out. “Guys,” I said, “we have nothing to lose. Here we are, in the gambling capital of the United States, with twenty bucks between us. Let’s see if we can parlay that into some kind of grubstake for the rest of the trip.” Not my sharpest reasoning perhaps, but to a bunch of young louts of the male persuasion it seemed the soul of judiciousness.

Reno in those days was even more of a stockman’s town than it is now. Cattle kings and cowboys—Andrew knew the town well—Indians off the nearby reservation, Basque sheepherders, and at this time of year, very few tourists. There was no “strip.” The casinos were all downtown. If you did not care for your luck in one joint, you just walked across the street. We chose Harold’s, mostly because I had heard of them: they used to circulate matchbooks all over the country with a cartoon of a naked guy in a high hat, walking around in a barrel. The caption read: “I was there.” On the basis of my acknowledged (by me) blackjack expertise, I was to be custodian of the treasury. Amazingly, the cards ran well. Betting no more than a buck at a time (all small bets were in silver dollars), it took me less than an hour to amass forty dollars in winnings. Time to redistribute. We divvied up the money, and Gary and Andrew went off to find their own tables. Red Chief stuck by my elbow, offering advice. By now he was calling me “Doc,” and refused to budge an inch. Betting such small amounts, it takes a long time to make any kind of money, but the cards still liked me and I persisted. Then a voice hissed in my ear: “Stand on sixteen, Doc. The dealer’s gonna bust.” I stood. The dealer busted. I had not won enough yet to see us on our way, but I was getting close, and A.K. was driving me nuts. I handed him a couple of silver dollars. “Here, kid,” I said nastily. “Go get yourself an ice cream cone.” He made a face at me and took off. Ten minutes later, while I was sweating over a possible five-card Charlie, he reappeared. “Here,” he said, displaying a hat full of silver dollars. “There’s more in my pockets. Let’s get out of here, this place bores the shit out of me.”

We rounded up our coconspirators, one of whom had also come out a winner, turned our clinkers into bills at the cashiers cage (except for A.K., who liked his hat full of silver), and went our way rejoicing. As we were leaving, I stuck my hand into my pocket and discovered a last silver dollar I had overlooked. What the hell; I dropped it into a slot machine by the door, and hit a goddamn jackpot. Not of Red Chief proportions, mind you, with bells and whistles, but another forty bucks or so. We were rich! Let the good times roll!

Now we could afford tire chains, food, gas, and a cheap room in a squalid motor court. We proceeded to do all of the above. We gorged ourselves festively that night in the dining room of a Basque boardinghouse. All you could eat for five bucks a head, and they kept our water glasses—A.K.’s included—filled with some of the most awful sour wine I have ever tasted. What the hell did we know from wine? We loved it. And so, merrily, to bed.

Next morning, somewhat subdued (oh God, that wine . . .) but with skid chains duly in place, we proceeded up and over Donner Pass, through the Sierras and some of the most spectacular scenery in the country. There was plenty of snow on the ground, but the day was glorious and the road was fine. Our morale was improving. Coming down into the foothills, someone said happily, “Open the windows, it’s stifling in here.” I did so, and received a blast of warm, moist, and vegetal Pacific air that was pure bliss. An hour later we spotted our first palm tree.

Early Days in Queens:

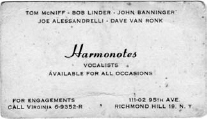

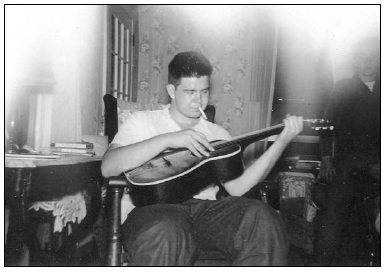

My mother and me, the Harmonotes’ business card, and portrait of an incipient juvenile delinquent with guitar. (All photos not otherwise credited are from the collection of Andrea Vuocolo Van Ronk.)

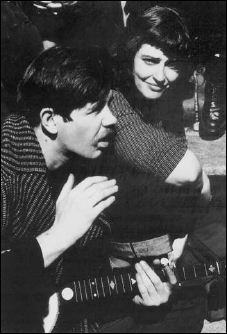

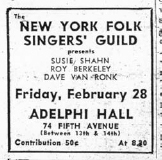

The 1950s: Jamming with Bob Yellin and Roy Berkeley in the Folklore Center; with Lee Hoffman in Washington Square (note the banjo); a Folksingers’ Guild ad; and the Bosses Songbook; Paul Clayton in his pith helmet; my card; warring personae: the hipster bluesman and the academic folksinger. (All photos: Photosound Associates: J. Katz, A. Rennert, and R. Sullivan.)

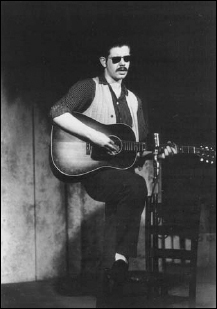

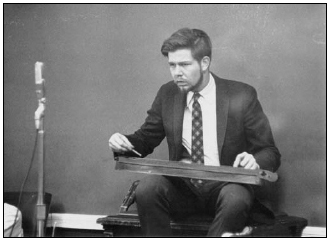

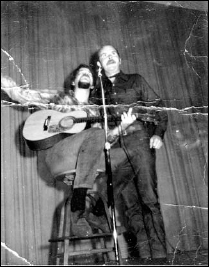

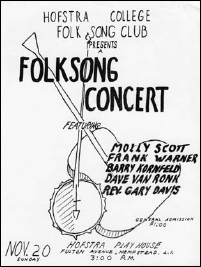

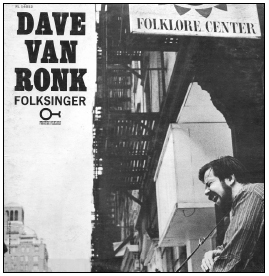

The Folk Scare Begins: The Reverend Gary Davis, with fans including Happy and Jane Traum (behind unknown bass), Dick Weissman, unknown, and John Gibbon with guitar (photo: Photosound Associates); me and Tom Paxton onstage at the Commons; a typical college concert poster; the blues workshop at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival, with John Hammond Jr., Mississippi John Hurt, Clarence Cooper, me, Sonny Terry, and John Lee Hooker (photo: Dustin S. Pease); the cover of the Folksinger album, in front of the Folklore Center on MacDougal Street.

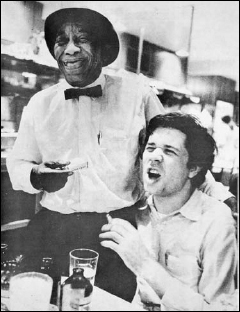

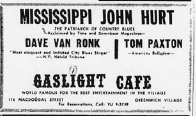

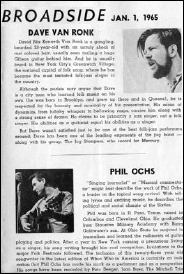

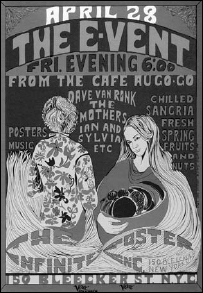

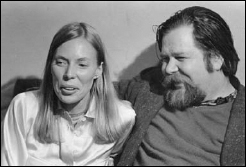

Glory Days: The Gaslight Café (photo: Don Paulsen); John Hurt and Patrick Sky in the Kettle of Fish (photo: Bob Campbell, courtesy of Patrick Sky); a Gaslight ad and the program for a Civil Rights concert; The Ragtime Jug Stompers at Newport, with Bob Brill, Barry Kornfeld, me, Artie Rose, and Sam Charters (photo: Ann Charters); a classic example of sixties psychedelia; with Joni Mitchell.

Times A-Changing: On the street with Suze Rotolo, Terri Thal/Van Ronk, and Bob Dylan (photo: Jim Marshall); going electric with The Hudson Dusters: Phil Namanworth, Dave Woods, Rick Henderson, and Ed Gregory.