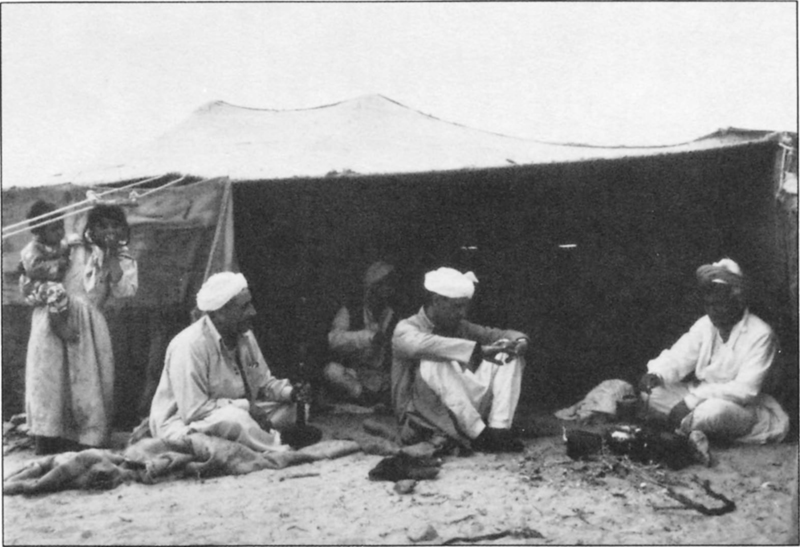

Kinsmen preparing tea in a desert camp

This world full of people whose lives I came to share was not at all what I had envisioned. Several romantic images had informed my subconscious expectations. Knowing that Awlad ʿAli inhabited a coastal strip along the northern edge of the Libyan Desert,1 I had imagined tents along a white-sand beach, the turquoise Mediterranean glimmering in the background. In my mind glowed a vivid passage from Justine, the first volume of Lawrence Durrell’s “Alexandria Quartet”:

We had tea together and then, on a sudden impulse took our bathing things and drove out through the rusty slag-heaps of Mex towards the sand-beaches off Bourg El Arab, glittering in the mauve-lemon light of the fast-fading afternoon. Here the open sea boomed upon the carpets of fresh sand the colour of oxidized mercury; its deep melodious percussion was the background to such conversation as we had. We walked ankle deep in the spurge of those shallow dimpled pools, choked here and there with sponges torn up by the roots and flung ashore. We passed no one on the road I remember save a gaunt Bedouin youth carrying on his head a wire crate full of wild birds caught with lime-twigs. Dazed quail. (1957, 34)

I discovered, however, that despite its proximity, the sea played little part in the Bedouins’ lives, and what appreciation of natural beauty they expressed was for the desert where, until sedentarization, their winter migrations had taken them. The members of my community all spoke with nostalgia about the inland desert, “up country” (fōg), although they had last migrated seven years before I arrived. They described the flora and fauna, the grasses so delectable to the gazelle, the umbellifer that whets the appetite, the herb that, boiled with tea, cures sundry maladies, the wild hares that must be hunted at night, and the game birds that suddenly take flight from deep within a shrub. They praised the good “dry” foods of desert life2 and disparaged as unhealthy the fresh vegetable stews that are now an important part of their diet. They recalled with pleasure the milk products, so plentiful in springtime when rains have created desert pastures,3 and savored memories of the taste of milk given by ewes who have fed on aromatic wormwood (shīḥ).

And yet, despite their appreciation of the desert’s natural gifts, the Bedouins think of the territory in which they live primarily in terms of the people and groups who inhabit it. Theirs is an intensely social world in which people’s activities and relationships are riveting, and solitude so abhorred that no one sleeps alone; those who spend time alone are thought to be vulnerable to attack by the evil spirits (ʿafārīt) who thrive wherever there are no people.

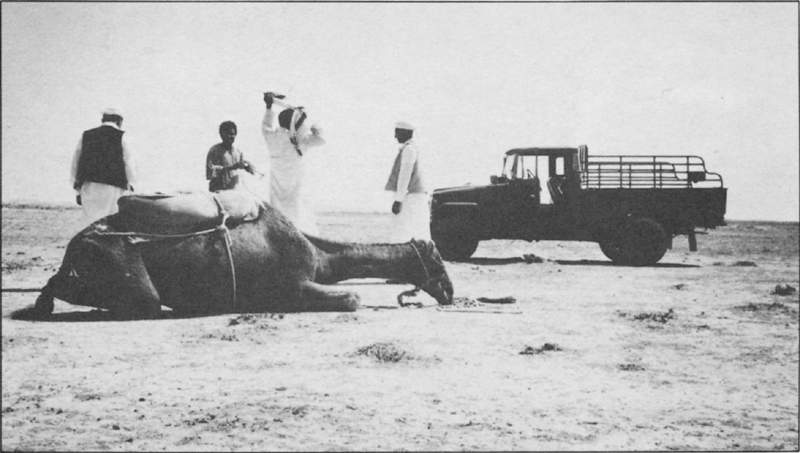

I had also expected tent-dwelling pastoral nomads who lived quietly with their herds but found instead that these same people who touted the joys of the desert lived in houses (even if they continued to pitch their tents next to them and spent most of their days in the tents), wore shiny wristwatches and plastic shoes, listened to radios and cassette players, and traveled in Toyota pickup trucks.4 Unlike me, they did not regard these as alarming signs that they were losing their identity as a cultural group, that they were no longer Bedouins, because they define themselves not primarily by a way of life, however much they value pastoral nomadism and the rigors of the desert, but by some key principles of social organization: genealogy and a tribal order based on the closeness of agnates (paternal relatives) and tied to a code of morality, that of honor and modesty. Their social universe is ordered by these ideological principles, which define individuals’ identities and the quality of their relationships to others. These principles are gathered up in Awlad ʿAli notions of “blood” (dam), a multi-faceted concept with dense meanings and tremendous cultural force, two aspects of which will be explored below.

Blood both links people to the past and binds them in the present. As a link to the past, through genealogy, blood is essential to the definition of cultural identity. Nobility of origin or ancestry (aṣl) is a point of great concern to Awlad ʿAli. The clans or tribes known as Awlad ʿAli migrated into Egypt from Libya. Most accounts concur in viewing them, like the other Saʿādi tribes of Cyrenaica, as descendants of the Beni Suleim and Beni Hilal, the Arab invaders from the Najd who swept through North Africa during the eleventh century. Some sources put their migration into Egypt at the end of the seventeenth century, although others favor the end of the eighteenth.5 Along with the Mrābṭīn, other ambiguously related tribal groups with whom they share the Western Desert, they have remained marginal to the agrarian society of the Nile Valley, the economic and demographic core of Egypt.6 By all estimates, the Bedouins of the Western Desert constitute far less than 1 percent of the total population of Egypt, a percentage that has probably been decreasing over the past century.7

The fortunes of Awlad ʿAli have always been tied to more than rainfall and the state of pasture, despite the fact that their traditional economy was based primarily on herds of camels, sheep, and goats, supplemented by rain-fed cereal cultivation in the littoral and some trade. Their movements and livelihood were determined not only by internal competition with other tribal groups who shared their way of life but also by external political and economic events affecting Libya and Egypt. They have been in contact with Europeans, Libyans, and Egyptians through trade, smuggling, and invasions, both peaceful and violent. Yet, despite centuries of contact with other groups and the efforts of successive central authorities in the Nile Valley—from Mohammad ʿAli through the British to Nasser and the current regime—to control and later to assimilate them, the Awlad ʿAli Bedouins maintain a distinct cultural identity.

In the nineteenth century, the free movement of Awlad ʿAli, their control over caravan routes, and their lack of respect for the law were a bane to Mohammad ʿAli. Finally, in exchange for their help in patrolling the borders, quelling internal rebellions, and assisting in foreign campaigns, he rewarded them with usufruct rights to the land in the Western Desert and with exemption from taxation and military conscription. By the time the British governed, the Awlad ʿAli were still far from subjugated or settled, although many had been induced to take up agriculture by the high value of cash crops, and the beginnings of competition from the railroad had loosened their hold on trade and driven them to concentrate on sheep rather than camels.8 The British, insecure about the nomads’ close ties to Libya and their smuggling activities, periodically and unsuccessfully sought to revoke their privileges to carry firearms and to claim exemption from military conscription. During World War II the Bedouins suffered the loss of herds, wells, and possessions when the battles between the British and Germans were fought on their soil.9

Only after the revolution and Nasser’s rise to power in 1952 did government goals shift from political control to assimilation. The motives underlying the government’s interest in integrating the Bedouins into the Egyptian polity, economy, and national culture were both ideological and material. As the anthropologist Ahmed Abou-Zeid explained in 1959, “Rightly or wrongly, it is generally assumed in Egypt that nomadism and semi-nomadism represent a phase of deterioration which is no longer compatible with the actualities of modern life and therefore should be abolished” (1959, 553). The government initiated projects to settle the nomads: it reclaimed land for agriculture; subsidized olive, fig, and almond orchards; subsidized fodder through the cooperatives; and made laws giving individuals who built a house the right to keep the land on which it was erected. The government also worked to improve pasture and herds, to encourage local industries, and to provide medical and educational services. In concert with Bedouin initiatives, primarily in commercial ventures, these projects radically altered the basic economy and work patterns of the Awlad ʿAli and contributed to sedentarization.10 Nevertheless, Abou-Zeid’s sanguine prediction about what impact government development projects would have on Awlad ʿAli rings hollow some twenty-five years later:

The crowning achievement of these projects will be the reduction of the cultural and social contrast which exists at present between the Western Desert, with its nomadic and semi-nomadic inhabitants, and the rest of the country. This contrast is manifested in the different patterns of social relationships, the different values and modes of thought, and the different structure prevailing in the desert and the Nile Valley. (1959, 558)

Despite many changes in Awlad ʿAli society and economy, the goal of assimilation has not been achieved. On the contrary, much of the Bedouin identity and sense of self is articulated through distinction from or in opposition to non-Bedouins, be they flūḥ (peasants), maṣriyyīn (Egyptians, Cairenes), or naṣāra (Christians).11 There are signs of integration into the state: most Bedouin men are aware of events in the world political arena, some hold opinions on the relative merits of the superpowers, and most have some knowledge of Egypt’s internal political situation as well as its international involvements. But their passions are aroused only by tribal affairs—intra-Bedouin disputes, reconciliations, alliances, and hostilities. They may hear Egyptian programs on the radio, but their excitement is reserved for one program called “Iskandariyya-Maṭrūḥ” (Alexandria-Matruh). Once a week young and old, men and women, crowd around small radios and listen with rapt attention and visible enjoyment to this program, which features traditional Bedouin songs, poems, and greetings for various parties, all identified by name and tribal affiliation.

The Bedouins’ sense of collective identity is crystallized in opposition to the Egyptians or peasants, who are lumped together as “the people of the Nile Valley” (hal wādi n-nīl). In the Bedouins’ view, the differences extend beyond the linguistic and sartorial to the fundamentals of origin, defined by genealogy, social organization, modes of interpersonal interaction, and a sort of moral nature.12 How accurate the Bedouins’ characterization of the Egyptians might be is not at issue. For Awlad ʿAli, the Egyptians with whom they share a country defined by political borders they consider arbitrary constitute a vivid “other,” providing a convenient foil for self-definition; by looking at how the Bedouins distinguish themselves from the Egyptians, we can isolate the nodes of Bedouin identity.

Blood, in the sense of genealogy, is the basis of Awlad ʿAli identity. No matter where or how they live, those who can link themselves genealogically to any of the tribes of the Western Desert are ʿarab (Arabs), not Egyptians.13 Awlad ʿAli more frequently refer to themselves as ʿarab than as badū (Bedouins). As in many cultures, the word they use to designate themselves also connotes the general term people—for instance anyone returning from a visit to kin is queried, “How are your Arabs?” But the term has a more specific meaning when used to distinguish the Bedouins from their Egyptian neighbors. In that context, it implies the Bedouin claim to origins in the Arabian Peninsula and to genealogical links to the pure Arab tribes who were the first followers of the Prophet Muhammad. It also suggests their affinity to all the Arabic-speaking Muslims of the Middle East and North Africa who, because of common origin, they presume to be just like themselves.

Blood is the authenticator of origin or pedigree and as such is critical to Bedouin identity and their differentiation from Egyptians, who are said to lack roots or nobility of origin (aṣl or mabdā). Some Bedouins stated this idea by characterizing the Egyptians as mixed-blooded or impure; others attributed to the Egyptians Pharaonic origins, as the following story told to me by one Bedouin man suggests:

When Moses escaped from Egypt, the Pharaoh and all of the real men, the warriors, set off after him. They left behind only the women, children, and servants/slaves [khadama]. These were the weak men who washed women’s feet and cared for the children. When Moses crossed the Red Sea, the Pharaoh’s men drowned chasing him. This left only the servants. They are the grandfathers [ancestors] of the Egyptians. That is why they are like that now. The men are women and the women are men. He carries the children and does not take a seat until he sees that she has.

The centrality of blood, in the sense of a bloodline, pedigree, or link to illustrious forebears, is apparent from these remarks. Underlying this concern is the belief that a person’s nature and worth are closely tied to the worthiness of his or her stock. By crediting the Egyptians with no line to the past or, more insulting, a line to an inferior, pre-Islamic past of servitude, this man was making a statement about their present worthlessness. The ignominy of origin is a metaphor for present shortcomings.

Nobility of origin is believed to confer moral qualities and character. Bedouins value a constellation of qualities that could be captured by the umbrella phrase “the honor code.” Although the entailments of this code will be detailed in the next two chapters, a few of the Bedouins’ criticisms of Egyptians will introduce the themes. Men variously described Egyptians as lacking in moral excellence (fadׅhīla), honor (sharaf), sincerity and honesty (ṣadag), and generosity (kurama), at the same time claiming these as Bedouin traits. One example they gave of Egyptians’ lack of honor was their insistence on using contracts in transactions—for the Arab, they explained, a person’s word is sufficient.

The most highly prized Arab virtue is generosity, expressed primarily through the hospitality for which they are renowned. As one Bedouin man put it, “We like to do [our duty to guests], not have done to.” To honor guests, ideally a sheep is slaughtered. If this is not feasible, a smaller animal may be substituted. Failing that, at least some food must be put out. No guest or even passerby can leave without being invited to drink tea. Of the Egyptians one man said, “It is rare for them to invite you to their homes. You are lucky if they invite you for a cup of coffee or tea, and that after you have invited them to your home, slaughtered a sheep for them, and given them everything it was in your power to give.” Some Bedouins also accuse the Egyptians of being opportunistic, of not knowing the meaning of friendship.

Fearlessness and courage are qualities considered natural in Bedouin men and women as concomitants of their nobility of origin. Although the days of tribal warfare are over, Bedouin men maintain the values of warriors, carrying arms and resorting to violence if challenged or insulted. Women support these values. All describe Egyptians as easily frightened and cowardly and lacking in the belligerence that, as we shall see, is so important in the ideology of honor.

Perhaps even more indicative of aṣl are moral qualities associated with relations between men and women. The Egyptians’ lax enforcement of sexual segregation and the intimacy husbands and wives display in public are interpreted as signs of Egyptian men’s weakness and the women’s immorality. (The connection between these will be elucidated in the following two chapters.) The pivotal role of sexual segregation in Awlad ʿAli definitions of their own culture was brought home to me on a visit to a settled Bedouin family living in Bhēra, an agricultural province. Genealogically Awlad ʿAli, this family of landowners lived on a large and productive agricultural estate, they dressed in that peculiar mix of peasant and urban garb common to the rural elite, and they spoke an Egyptian rather than a Libyan dialect. When I challenged them, the women adamantly defended their Arab identity. One argued, “We are not like the peasants. Their women go out and talk to men. We never leave the house, we don’t drink tea with men, and we don’t greet the guests.”

That the Bedouins attribute the ease of social intercourse between men and women and men’s show of affection toward women to men’s weakness is clear in the story of the Pharaonic origins of the Egyptians recounted above. The point was made that the servants left behind were those who “washed women’s feet and cared for the children.” To this day, the man who told me that story said, Egyptian men were weak and doted on their wives. The antiquity of this view of Egyptians is attested to by Lord Cromer’s comment in 1908 that “the Bedouins despise the fellaheen [peasants], whom they consider an unmanly race” (1908, 198). Many Bedouin men and women echoed this man’s sentiments:

Among the Arabs the man rules the woman, not like the Egyptians whose women can come and go as they please. When an Egyptian family goes out, the man carries the baby and the wife walks in front of him. Among the Arabs, a woman must get permission to go visiting. Among the Arabs, if there are guests in the home, a wife can come to greet them only if they are kinsmen. She does not stay in the room. If they are nonkin, she does not enter at all.

Further evidence of the reversal of proper power relations is the alleged public affection Egyptian husbands show their wives. Stories of men cooking for bedridden wives, bringing them flowers, or doing them other favors provoked strong reactions in Bedouin women and men alike. The women’s disapproval was tempered by an occasional wistful comment such as “the Egyptians spoil their women—they love their wives,” but Bedouin men were less equivocal. They considered such behavior simply unmanly and a testament to female rule (which is not to deny that many of them felt affection for their wives and treated them with respect).

The other side of the coin to men’s weakness is women’s immodesty. Once two women giving me advice about what to do when I got married earnestly confided, “You should not let the groom have sex with you on the first night.” I argued that we knew for a fact that a certain bridal couple had consummated their marriage the first night. They countered, “Oh, she is a peasant. They don’t care. They have no shame [mā yitḥashshamūsh].”14 They laughed uproariously as they recalled another peasant woman who had announced to her women guests the morning after her wedding that her husband had made love to her twice, and added, “She had no shame at all!” Bedouin brides vehemently deny that sexual intercourse has taken place, even when it is obvious to all that it has. One woman put it this way:

The Egyptians are not like us. They have no shame. Why, the So-and-So’s [an Egyptian family we knew] have a photograph from their wedding hanging on the wall in their living room where everyone can see it. In it, he has his arm around her. And they sit together and call each other pet names. An Arab woman would be embarrassed/modest [taḥashsham] in front of an older brother, her mother-in-law, people.

Many of the ideas the Bedouins have about Egyptians are based on hearsay and the imposition of their own cultural interpretations on reported behavior. Very few of those living in the desert have much opportunity to see Egyptians at home. But, as the following incident shows, when they do have such opportunities, their ideas are confirmed. During the holidays celebrating the Prophet’s birthday, an Egyptian army officer, a friend and business partner of the Haj, decided to bring his family for a weekend visit to the Western Desert, and they spent a day and a night with us before going on to a beach resort. Their visit occasioned a great deal of commotion, including the purchase and preparation of special foods, a massive cleanup, and the household’s rearrangement to vacate rooms for their comfortable accommodation. The visit strained everyone’s nerves and energy, but it provided an intriguing close-up look at the Egyptians.

Everyone knew about the Egyptians’ lax sex segregation, so they were not surprised that the women and girls ate with the men and spent time as a group in the men’s guest room. However, the evening’s events were unexpected. After dinner, the man, his wife, their daughters, and his wife’s sister all retired to their rooms, only to emerge in nightclothes and bathrobes and go to the men’s guest room, where they sat chatting with their host and his brothers. This immodesty of dress sent shock waves through the community. Next came the scandalized realization that husband and wife intended to sleep in the same room. Although Bedouin husbands and wives sleep together under normal circumstances, they would not do so when visiting; each would sleep with members of his or her own sex. In fact, it is considered rude for a host or hostess not to sleep with his or her guests. The public admission of active sexuality implied by the couple’s wish to sleep together was considered the height of immodesty. Yet everyone was polite, the values of friendship and hospitality outweighing the deeply offended sense of propriety. Perhaps more important, the Bedouins excused their guests’ behavior because they recognized that the Egyptians were another sort of people, whose lack of pedigree made it difficult (although not impossible) for them to behave with honor.

The concept of blood is central to Bedouin identity in a second sense: through its ideological primacy in the present, as a means of determining social place and the links between people. Above all, Awlad ʿAli conceive of themselves in terms of tribes, notoriously ambiguous segmented units defined by consanguinity or ties to a common patrilineal ancestor.15

This tribal social organization is another point on which the Awlad ʿAli proudly differentiate themselves from their Egyptian neighbors, whom they disparage as a “people” (shaʿb)—meaning that the Egyptians are not organized tribally, do not know their roots, and identify with a geographic area or, worse, with a national government. The importance of blood in social identity is apparent in the identification of Bedouins by family, lineage, and tribe. One of the first questions asked a newcomer is “Where are you from?” The answer to this question is not a geographical area (that would be the response to another question, “Where is your homeland [wuṭn]?”) but rather a tribal affiliation. Because Awlad ʿAli apply the term tribe (gabīla) to many levels of organization, people belong to numerous named tribes simultaneously.16 The tribe a person chooses to identify with at any given moment depends largely on the rhetorical statement the speaker wishes to make about his or her relationship to the inquirer. To assert unity and closeness, a person will point to the shared level of tribal affiliation (a common ancestor), establishing himself or herself as a paternal kinsperson of the appropriate generation.

The tribal terms in which Bedouins conceive of social bonds lend a distinctive cast to their social life. Most of the anthropological literature on Bedouins has focused on how kinship provides an idiom for political relations. I am less concerned with whether the Bedouins really organize politically in terms of segmentary lineages (Peters 1967) or with how the theory of segmentary opposition, the genealogical ordering of political life, and kinship and affinity relate to Bedouin economy and ecology (Peters 1960, 1965, 1967, 1980; Behnke 1980) or even to the historical problem of uncertain political relations (Meeker 1979) than with how kinship ideology shapes individual identity and the perceptions and management of everyday social relations. This is not to deny either the importance of kinship as the language of socio-political organization or the dialectic between the political and interpersonal spheres, as later arguments will show. It is merely to shift the focus to kinship as the idiom for Awlad ʿAli feelings about, and actions toward, persons in their social world, in order to show how deeply this ideology penetrates everyday life and sentiment.17

The social world of the Awlad ʿAli is bifurcated into kin versus strangers/outsiders (garīb versus gharīb), a distinction that shapes both sentiment and behavior. Bedouin kinship ideology is based on two fundamental propositions. First, all those related by blood share a substance that identifies them, in both senses of the word: giving each person a social identity and causing individuals to identify with everyone else who shares the same blood. Agnates share blood and flesh (dam wlḥam), although the fact that a relationship through maternal ascendants is characterized as one of dmāya (the diminutive of “blood”) suggests that the Bedouins do recognize distant maternal links as a weak form of kinship. Second, because of this identification with each other, individuals who share blood feel close.

The term for kinship is garāba, from the root meaning “to be close.” The Bedouin vision of social relations is dominated by this ideology of natural, positive, and unbreakable bonds of blood between consanguines, particularly agnates, including putative or distant agnates, those related through common patrilineal descent as manifested by a shared eponymous ancestor. Tribal bonds, or relations between paternal kin, are called ʿaṣabiyya, which one man expressively characterized as “son-of-a-bitch bonds you can never break.”18 The Bedouins look down on the Egyptians, alleging that they know no one but their immediate kin.

Agnation has indisputable ideological priority in kin reckoning. Descent, inheritance, and tribal sociopolitical organization are conceptualized as patrilineal, extending the strong relationship between father and son (and father and daughter) back in time and outside the immediate family. The significance of agnation is reflected in how rights are distributed among members of a family. For one thing, children take their father’s tribal affiliation, although their mother’s affiliation affects their status (Abou-Zeid 1966, 257). In case of a divorce, the mother has no right to keep her children, although she may temporarily take unweaned children with her and she may set up a separate household with adult sons. The superior claim of agnates to children was expressed in a comment I heard one woman (a paternal first cousin of her husband) make to her co-wife in the midst of a heated argument. She asserted, “Your son is ours, and even if we decide to sacrifice him [like a sheep], you have no right to say a word.” The hyperbole produced by flared passions does not invalidate the essential message—that paternal kin have jural rights to all children born to wives of agnates.

The Bedouins consider this not just a right but also a natural bond based on sentiment, as is clear from the following story I heard about a neighbor of ours. This woman was divorced by her husband after he had brought her to her natal home for a visit and never returned for her. Her young son, considered too young to part from his mother, was with her. After a year, the boy’s paternal grandfather came to the house to take his grandson back. According to reports, he asked his five-year-old grandson, “Would you like to come with me?” Although the boy had never seen him before, he ran to pack a few clothes, put his hand in his grandfather’s, and left with hardly a glance back. His mother was heartbroken. Men who heard the story nodded their heads and did not seem surprised; “Blood” was all they said by way of explanation. Although women, too, perceive social relations and identity primarily in terms of agnation, their experiences lead them to a slightly different position. Many of their closest relationships, to their children and to coresident women in their marital communities, are not those of agnation. Most of the women who heard the story were moved and reacted differently, wondering if the grandfather had used magic (katablu) to lure the boy into abandoning his mother.

Much has been written on the close (if often troubled) relations between men, especially brothers, in patrilineal, patrilocal societies. Yet the position of women and attitudes about the bonds created by marriage give the clearest index of the ideological dominance of agnation in social identity and relationships in Bedouin society. A woman retains her tribal affiliation throughout her life and should side with her own kin in their disputes with her husband’s kin; I heard many stories of women who left for their natal homes, abandoning children, under such conditions. In her marital camp people refer to her by her tribal affiliation, and she may refer to herself as an outsider even after twenty years of marriage.

The extent to which women remain a part of their own patrigroup is clear from the following incident. In one camp, when a paternal aunt of the core agnates died, her nieces and nephews all agreed that it would have been better if she had come to spend her last days with them and died and been buried in her father’s camp. Even after forty years of married life away from the camp, they considered it her true home. Of the five people who washed her corpse, only one was from her husband’s family; the others were her sisters and her brothers’ wives. Although a woman can never be incorporated into her husband’s lineage, if she has adult sons she becomes secure and comfortable in her marital community. Once her husband dies and she becomes head of the household, her close association with her sons makes her seem the core of the agnatic cluster. There are many such matriarchs.

Not only do women derive their identities from their patriline, but they also retain their ties to their kin, even after marriage, for both affective and strategic reasons. A woman remains dependent on the moral, legal, and often economic support of her father, brothers, or other kinsmen. Only they can guarantee her marital rights. A woman cut off from her family is vulnerable to abuse from her husband and society (Mohsen 1967, 157), but a married woman with the backing of her kin is well protected. When mistreated or wronged, she argues that she need not put up with such treatment because “behind me are men.” When angry, she packs a few of her possessions in a bundle and heads off toward her family’s camp. And in case of divorce, she can return home, where she is entitled to support. But because she is identified with her kin, her behavior affects their honor and reputation, just as theirs affects hers. Her kin, not her husband, are ultimately responsible for her and are entitled to sanction all her wrongdoings, including adultery.

Although strategically useful, these kin ties are conceived of as based on sentiment. The sense of closeness, identification, common interests, and loyalty is expressed in the way women talk about their kin and in their attitudes toward visits home and even toward visits by their kin. Women are preoccupied with news of their kin. They rush home (if their husbands permit) whenever an event is celebrated or mourned: if they hear of an illness, a wedding, a circumcision, a return from the pilgrimage, a release from prison, or a funeral, they visit, and they are dejected and frustrated if for some reason they cannot. When a young wife left our camp “angry” without any apparent reason, some of the men suspected magic, but the women thought it more plausible that she just missed her relatives and wished to see her brother, who had just been released from prison. Her husband had been too busy to take her home for a visit, and she had been crying for days.

Visits home are anticipated with excitement, suffused with warmth, and remembered nostalgically. Women always return from such visits reporting how happy, pampered, and well fed they were. They bring back gifts, dresses, jewelry, soap, perfume, and candies. Their hair is freshly braided and hennaed, smelling sweetly of expensive cloves—kinswomen’s grooming favors. And when a brother or other kinsman visits a woman’s marital home, although sexual segregation may sometimes prevent her from sitting with him, she will certainly offer the choicest provisions and devote herself to the preparations personally, rather than delegating her responsibilities to grown daughters or younger co-wives. The tone of their greetings, however brief, invariably betrays affection.

Marriage presents serious problems for the consistency of an ideological system in which agnation is given priority over any other basis for affiliation. The Awlad ʿAli commitment to this system is expressed in their contempt for the perceived Egyptian propensity to reside in nuclear family units, a shameful sign of the valuation of marital ties over agnatic ones. One man said, “Arabs say that mother, father, and brother are the most dear. Even if an Arab loves his wife more than anything, he cannot let anyone know this. He tries never to let this show.”

The way to resolve this problem of marriage is to fuse it with identity and closeness of shared blood. Patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage may be preferred because it is the only type consistent with Bedouin ideas about the importance of agnation (see chapter 4). As in other parts of the Middle East, this type of marriage is the cultural ideal, although it is only one of many types of marriage practiced. Because of the prevalence of multiple kinship ties between individuals (Peters 1980, 133–34) and because the term paternal cousin extends to all members of a tribe (however widely defined), a range of marriages can be interpreted as conforming to this preferential type and will be justified in terms of this preference even when arranged for other reasons. Thus, even if cousins are more directly related through some maternal link, their relationship will be described in terms of the paternal one.19 The actual frequency of cousin marriages varies depending on a number of circumstances that are too complex to explore here but that have been much debated in the theoretical literature (see Bourdieu 1977, 32–33). The actual incidence in any particular community is, however, less important than the ideological preference. In the community in which I did my fieldwork, the incidence happened to be quite high. Four of the five core household heads had married their paternal first cousins (FBD); of those who took second wives, three married more distant cousins, women from another section of their tribe. In this generation, the eldest daughter and eldest son of two brothers had married, and the brothers planned to marry other sons and daughters to each other in the near future.

What differentiates marriage to paternal kin from other types of marriage, and how are the differences evaluated? For most, the advantages do not have to do with sexual excitement. Indeed, some older men complained that the “marital” (sexual) side of such marriages was limited. As one polygynously married man put it, “My other wives are better with me personally,” although he went on to explain that he nevertheless preferred his cousin-wife, for reasons to be enumerated below. Certain young men complained that the trouble with marrying a cousin was that she was like a sister.20 An unmarried man mused, “You won’t feel like talking and flirting. And she knows everything about you, where you go, who you see.” He implied that she would therefore not be in awe of her husband, reducing the power differential. Girls occasionally voiced a wish to see something new by marrying an outsider, since then they would leave the camp. They did not talk (at least to me) about the sexual aspect of marriage.

The advantages of such marriages are that they presumably build on the prior bonds of paternal kinship to take on the closeness, trust, identification, and loyalty appropriate to such bonds. In polygynous unions, the wife who is a paternal kinswoman is usually better treated than her co-wives. The young man who complained that there was no mystery with a cousin-wife also claimed that he would not beat her as much as he would an outsider. And the older man who confessed the lack of sexual excitement with his cousin-wife considered this wife to be first in his affections and in charge of his household. His other wives had tried in vain to displace his cousin in his affections, something he claimed was impossible because,

after all, she is my father’s brother’s daughter. I know that if I am gone, she will take care of the house, entertain my guests graciously, and protect my property and all of my children. Haven’t you noticed how even though she loves her own children more, she cares for the children of my other wives, even protecting them from their mothers’ harshness? After all, the children are closer to her, they are her kin, her tribe. Also, if something is on my mind, it will be on her mind too. Outsiders don’t care. They don’t care who might enter the house while I am gone, what gets spilled, ruined, or stolen. They don’t care about your name or reputation. But a father’s brother’s daughter cares about you and your things because they are hers.

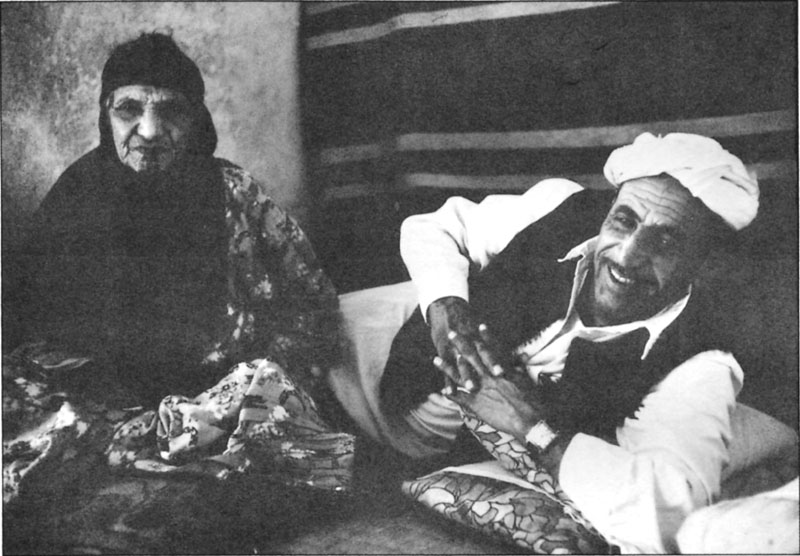

Another man, even though he was no longer sleeping with his postmenopausal wife, treated her as head of the domestic household, entrusted her with all his money and valuables, and took only her with him on important visits. He explained, “I take my father’s brother’s daughter with me when I go to visit outsiders because I trust her.” Nearly all the young children born to his other wives slept with her, ate with her, and spent more time with her than with their own mothers. They called her ḥannī, or grandmother, the person for whom children feel the deepest affection.

Women see innumerable advantages in this marriage arrangement. As wives, they are more secure and powerful if they marry paternal kin because they remain among those whose duty it is to protect them. They are not as dependent on husbands, since their right to support derives from their claim to the common patrimony. They also feel comfortable in the community, living among kinfolk with whom they share interests, loved ones, and often a lifetime of experience. Even if the match does not work out, they need not leave their children. Marriages between coresident cousins are often more affectionate because they build on childhood experiences of closeness, in a society in which relations between unrelated members of the opposite sex are highly circumscribed and often either distant or hostile (see chapter 4).

In contrast, wives who are not patrikin to their husbands are often treated differently from wives who are paternal cousins or, even more, mothers and sisters of the core agnates. In the camp in which I lived, the men tended to overlook or skimp on gifts to these outside women at festive occasions such as weddings when men buy clothing and jewelry for the camp’s women. In defense, the outsider wives tended to form alliances with one another, but this process was not haphazard either: agnation created special bonds even between in-marrying wives. Two women from the same tribe who had married men in my camp spent a great deal of time together, helped each other with work, and supported each other in arguments. If one was angry with a certain person or family, the other would also refuse to speak to them. Thus, whatever the material consequences,21 marrying agnates protects women from having to be vulnerable to people who do not have their interests at heart and keeps them close to sources of support, and it saves men from having to bring into their households women whose primary loyalties and interests lie elsewhere.

As we have seen, consanguinity provides the only culturally approved basis for forming close social relationships in Awlad ʿAli society. However, agnation, although primary, is not the only factor informing social identity and social relationships. Awlad ʿAli individuals unite on a variety of other bases, usually trying to couch these in the idiom of kinship.

Besides agnation, the two most important bonds between individuals are maternal kinship and coresidence (ʿishra). On the surface, these two bases for forming relationships might seem to lie outside the dominant principle of agnation, but the Bedouins do not perceive them so. Using different conceptual means, they reconcile each with the ideology of lineage organization, subordinating both to the principle of paternal kinship.

Their task with regard to maternal bonds is made simpler by the fact that the distinction between maternal and paternal kin is not always clear-cut. Patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage fuses maternal and paternal ties. As Peters (1967, 272) also points out, the density of overlapping ties created by intermarriage within the lineage and by continual exchanges of women between the same two lineages over several generations also clouds the question of whether behavior and sentiment conform to the jural rules. But at least in conversation, and when applying kin terms, the Bedouins tend to give priority to the ties between agnates in cases where multiple connections can be drawn. Thus, in the camp I lived in, the children of the two brothers who had married two sisters who were their paternal first cousins always called their uncles and aunts by the term for paternal, not maternal, uncle and aunt (sīd, ʿamma, not khāl, khāla).

In general, individuals and their maternal kin share bonds of great fondness and a sense of closeness, but maternal descent hardly defines social identity, because it cannot be carried further than one generation, and it does not provide a strong sense of identification with others. The only hints of belief in shared substance are proverbs proclaiming the children’s resemblance to their maternal uncles. The honor of the matriline can touch a woman’s children in refining their status vis-à-vis the children of her co-wives. The factors that reinforce social relationships based on agnation, such as shared jural responsibility, common property, or coresidence, rarely support maternal bonds. But the tie symbolized in the word dmāya (the diminutive of “blood”) carries with it sentiments of loyalty and amity and obligations of reciprocal attendance and gift giving at ritual occasions.

This closeness to maternal kin does not conflict with the principle of agnation. In fact, a careful look at the relationship between a woman’s kin and her children will reveal that the maternal bond derives indirectly from agnation itself. First, because adults, not children, initiate relationships, the bond to a woman’s child is an extension of the bond between the woman herself and her paternal kinfolk. As one man explained, “A woman is always part of her tribe, even when she marries outside of it,” so her kin care about her children because they care about her. They certainly shower affection on both when they come for visits. Indirect evidence of the way Bedouins conceive of such relationships can be found in the kinship terms for nephew and niece, which are built on siblingship: all nephews and nieces, however distant and whatever generation, are called “sister’s son” or “brother’s son” (ibnakhiyyi or ibnakhītī). From the point of view of those who initiate relationships, the bonds to nephews and nieces are consistent with the bonds of agnation, since these are merely the children of paternal kin.

In Bedouin society, relationships between mothers and children are, with few exceptions, extremely close and affectionate throughout life. Based on initial dependency and later concern, the mother-child bond is taken for granted, and it presents the only undisputed and undisguised exception to the rule equating closeness with agnation. Once children are older, after having lived with and come to identify with paternal kin, they feel affection or some sort of link to maternal kin as an extension of their affection for their mothers. If they love their mother, they will love those with whom she identifies and is identified. Thus, from the child’s perspective, maternal kin are neither confused with nor in competition with paternal kin; they are merely thought of as the mother’s agnates. If anything, the competition is between mother and father, as highlighted in the playful questioning of one father who, as his wife sat nearby, tickled his two-year-old daughter and asked over and over, “Whose daughter are you? Are you your father’s daughter or your mother’s?”

The other type of close relationship in Bedouin society is that between nonkin who live together, or, as one man described it, garāba min l-galb (kinship from the heart). By a logical reversal, Awlad ʿAli justify the development of close bonds between individuals who are neither maternal kin nor from the same tribe or who, although from the same tribe, are genealogically distant. Since close genealogical kin ideally live near each other, coresidence and paternal kinship are strongly associated. By a subtle shift, those who live together develop relationships similar to those between paternal kin. In talking about such relationships, Awlad ʿAli tend to stress the link of paternal kinship, however distant—if it exists at all. Where there is no genealogical link, the nature of the relationship is downplayed, and kinlike bonds are created through actions.

The bond of living together or sharing a life is called ʿishra. Although marked by impermanence,22 it suggests the kinlike bonds of enduring sentiments of closeness, as well as a more or less temporary identification and the concomitant obligations of support and unity. The bond is symbolized by the notion of sharing food, which in Bedouin culture (like many others) signifies the absence of enmity. The expression used to describe a relationship based on proximity or a shared life, ʿēsh wmliḥ (cereal and salt), applies to husbands and wives, past and present neighbors, and patron and client families alike.

With sedentarization, the variety and permanence of neighbors has changed. Within the settled hamlets, neighbors become quasi-kin: they visit and assist each other at feasts marking circumcisions, weddings, and funerals and at births and illnesses, and they respect the mourning periods of neighboring families. They stand together politically in confrontations with other groups, especially those living nearby. They also spend a good deal of time together.

Many camps and hamlets, especially the wealthier ones, include a number of families or individuals who have attached themselves to the group, or to particular men, as clients. In the camp I lived in there were five such households, all so closely tied to the core families that I initially mistook them for kin. Some were indeed distant kin, a status that was stressed, but most were not, and their tribal identity was played down except in crisis situations. Yet, like kin, most had spent their whole lives in the community. For example, one family consisted of a young man, his wife and two children, and his old blind father. The old man had been a shepherd to the fathers of the core agnates, as had his father before him. The women and children called the old man by the kinship term for close paternal uncle (sīd), since older people in the community are rarely referred to without a kinship term. The young man was a constant visitor in the core households, entertaining guests when the patrons were absent or assisting in serving meals when they were present, helping with work, and so forth. He played a social role similar to that of the core agnates’ nephews, to whom he was in fact very close.

Another client family had lived with the group for over thirty years. The head of the household had initially joined the camp as a shepherd, and he eventually entered into a partnership with one of his patrons. While I was there, his patron’s brother decided to marry the old man’s attractive young daughter. It was interesting to see how her attitude and those of the other camp women differed from that of a bride who married into the camp from outside at the same time. The outsider bride was uneasy, and people were tense around her. This was not true of the client’s daughter—the bonds of ʿishra already tied her to all the others in the camp. When I remarked on the difference, people explained, “She was born in the camp. There is no strangeness [ghurba]. Everyone is relaxed.”

Merely living together confers rights and obligations comparable to those of kinship, as is evident in the following two examples. A woman who was both sister to the men in the core community and a neighbor (having married a man of a different lineage who lived nearby) was indignant at not having been invited to accompany her kinsmen to her brother’s engagement feast (siyāg) or to the bride’s ritual visit home after the wedding (zawra), where meat is plentiful and the groom’s kinswomen need not work. As part of her appeal for justice, she argued, “I’m their sister! Why, even as a neighbor I should have gone!” Another woman, scolding someone for not assisting her pregnant kinswoman, told of a woman whose neighbor—“not even a relative!”—had baked her bread, brought her water from the well, and even washed her clothes for her.

It is not enough to argue simply that because kin usually live together, those who live together are conceived of as kin. The question is, why does living together create such strong bonds? Because the relationships that develop are upheld not by jural responsibilities but by strong sentiment, I think the key lies in Bedouin attitudes toward “familiarity.” The term mwallif ʿale (to be used to or familiar with) is most often used to describe a child’s feelings of extreme attachment to caretakers other than its mother (usually a grandmother, older sister, or father’s wife), as evidenced by the child’s violent protest when forced to part from the caretaker, miserable crying, and refusal to eat or be comforted. The term was also used in conjunction with the idea of a homeland; people explained that they felt uneasy and “didn’t know how to sit or stay” in territories they were not used to. Thus the idea of attachment to the familiar emerges. Living together makes strangers familiar and hence more like kin, who are automatically familiar by virtue of being family.

Shared blood signifies close social relations only because it, in the Awlad ʿAli conception, identifies kin with one another. Kin share concerns and honor; ideally they also share residence, property, and livelihood.23 They express this sense of commonality through visiting, ritual exchanges, and sharing work, emotional responses, and secrets. In times of trouble their fierce loyalty sometimes leads them to take up arms together and, in the case of homicides, is institutionalized in the corporate responsibility for blood indemnity (diyya).

This strong identification with patrikin manifests itself in several ways. First, in many contexts individuals act as if what touches their kin touches them; an insult to one person is interpreted as an insult to the whole kinship group, just as an insult to a kinsperson is interpreted as an affront to the self. A woman, threatening to leave her husband for slurring her father’s name in the heat of a marital dispute, appealed to anyone who would listen, “Would you stay if anyone said that about your father?” Likewise, one family member’s shameful acts bring dishonor on the rest of the family, just as everyone benefits from the glories of a prominent agnate or patrilineal ancestor. The rationale for both vengeance for homicides and honor killings (in practice extremely rare) is that an affront to one individual or a shameful act by one person affects the whole group, not just the individual.24

Second, people are perceived, at least by outsiders, as nearly interchangeable representatives of their kin groups. When a host honors a guest, the assumption is that he honors the person’s whole kin group, which explains why sheep are sometimes slaughtered for women guests or individuals who are not especially important personally. Members of my adopted family eagerly asked how I was treated whenever I visited people outside our camp, because they took it as an index of the esteem in which they were held. Only one member of an agnatic cluster need actually attend ceremonies of outside groups to fulfill the obligation of the whole group. In arranging marriages, the individuals are less important than the kin groups involved. Men would arrive at our camp and request “one of your girls” in marriage, apparently caring little which one, since they had chosen the family to nāsib (create an affinal relationship with). Some of these men were refused because of grudges against their kin groups. Even close personal ties with the men of our camp, in one case due to maternal kinship, were overshadowed by the suitors’ tribal affiliations and the state of intertribal relations.

People often describe the existence of bonds between people, whether based on paternal or maternal kinship or just a common life, by using the phrase “we go to them and they come to us” (nimshūlhum wyjūnā). This expression conveys nicely the way bonds between individuals are expressed and maintained. “Coming and going” refers to reciprocity in both everyday visiting and ritualized visiting on particular occasions (munāsabāt), usually those marking life crises or transitions. Since these occasions are unofficially ranked in order of importance, failure to attend some is interpreted as a sign that the relationship has been terminated and the bond broken.

The impetus for such visits is identification (the sense that what happens to kin is happening to the self) and the desire to be with those who share one’s feelings. Visits also provide occasions for strengthening identification between those who already have bonds. This is most obvious in the least ritualized visits, those undertaken in times of trouble or illness. During my first two months in the field, my host was mysteriously absent for a stretch. Guests kept appearing at our household, and many stayed. At the time, I did not know enough to realize that this constant flow of visitors was unusual; I merely thought that the Bedouins were indeed very sociable people. When my host returned, there was a celebration, sheep were slaughtered, and guests were plentiful and lively. I later understood that he had been detained for questioning by government authorities; everyone had been worried that he had been arrested, and they had gathered out of concern, to be with those closest to him and thus most affected. After his safe return, well-wishers came by to share their relief. Visits to the ill follow a similar protocol. Failure to visit a person who is ill is taken as an insult and a breach in relations precisely because it is a departure from what would be a “natural” concern for the well-being of those you love.

The worst form of trouble, of course, is death. Not to go to a camp in which a person has died, if you have any link either to that person or to his or her relatives or coresidents, is to sever the tie. I will describe funeral rituals in greater detail in chapter 6, but a brief look at one aspect of women’s mourning behavior will clarify the participatory quality of ritual visits. Women who come to deliver condolences (yʿazzun) approach the house or camp wailing (yʿayṭun), and then each squats before those family members to whom they are closest and “cries” (yatabākun) with them. This ritualized crying is more than simple weeping; it is a heart-rending chant bemoaning the woman’s own loss of her closest deceased family member, usually a father. When I asked about this unusual behavior, one woman explained, “Do you think you cry over the dead person? No, you cry for yourself, for those who have died in your life.” The woman closest to the person whose death is being mourned then answers with a chant in which she bemoans her loss. Women speak of going to “cry with” somebody, suggesting that they perceive it as sharing an experience. What they share is grief, not just by sympathizing, but also by actually reexperiencing, in the company of the person currently grieving, their own grief over the death of a loved one. Not only may such shared emotional experiences enhance the sense of identification that underpins social bonds, but participation in rituals that express sentiments might also generate feelings like those the person directly affected is experiencing, thus creating an identification between people where it did not spontaneously exist. The same process might apply to happy occasions celebrating weddings, circumcisions, return from the pilgrimage to Mecca, or release from prison.

Going and coming is accompanied by the exchange of gifts, animals for slaughter, money, and services.25 I would argue that these exchanges are considered not debts, as Peters (1951, 166–67) maintains, but acknowledgments, in a material idiom, of the existence of bonds. Although gifts and countergifts are essential to social relationships, they do not establish relationships; rather, they reflect their existence and signify their continuation. If gift giving occasionally takes on a burdensome quality, it is because individual experience and contingencies of personality and history can never be fully determined by the cultural ideals of social organization.

Sharing is the common theme that runs through these ways of expressing and maintaining bonds. Visits are prompted by the sense of identification felt with individuals to whom one is close, and they provide occasions for participating in emotionally charged events that increase the basis of what is shared. By giving gifts of both material goods and services people share what they have. As we shall explore in the second half of this book, sharing thoughts and feelings, especially ones that do not conform to the ideals of honor and modesty, is also a significant index of social closeness.

The profound changes that currently affect the Awlad ʿAli interact in complex ways with the ideology of blood outlined above. Kinship is still the dominant ideological principle of social organization, and despite the different look of the land, settlement patterns are marked by continuity. Although clusters of houses and tents like those described in the first chapter are today more common than the traditional scattered encampments of between two and ten tents, both are called by the same name (najiʿ, pl. nawājiʿ) and are seen as similar. The dwellings may be permanent, but the communities, which take the name of the group’s dominant lineage or family, remain socially rather than territorially defined units.

The new economic situation created by the Bedouin involvement in a cash economy—through smuggling, legitimate business, land sales, and agriculture—has radically altered both the volume and distribution of wealth. Because an economy based on herds and simple cereal cultivation depends on rainfall, assets are precarious in a region that averages two to four inches of rain per year and has drought periods every seven years or so. Herds can be wiped out in a season. Rain might or might not fall on a sown plot. Although there have always been rich and poor among the Bedouins, fortunes often reversed unpredictably, and a concentration of wealth in the hands of any one person or family was never secure. Now social stratification has become more marked and fixed: the wealthy have the capital to invest in lucrative ventures and the poor do not.

Perhaps even more important for consolidating social and political power has been the gradual expansion of the types of resources that can be privately owned, which has enabled some people to make others dependent and thus to control them. Whereas formerly, economic, political, and social status were not tied—as status and leadership were based largely on genealogy and achieved reputation, and dependency implied less economic helplessness—today they are becoming increasingly coterminous.

However, disintegration of the tribal system is hardly imminent. Kinship ties still crosscut wealth differentials, and the vertical links of tribal organization overshadow the horizontal links of incipient class formation. Although individual ownership and private control of resources are beginning to undermine the economic bases of the tribal system, the tribe remains ideologically compelling. Ironically, the cooperative societies the government introduced to break down the lineage system instead served to strengthen lineage loyalties, because the new resources made available were distributed following lineage lines by the traditional lineage heads who had assumed leadership in the new system (Bujra 1973, 156).

The new levels of wealth have even allowed the realization of traditional ideals of lineage solidarity unattainable in the traditional economy. For instance, greater access to wealth and opportunity has reduced some of the pressure on lineages to fission, enabling extended families to remain coresident units. Stein notes that in the new situation “the individual members of the extended families have each specialized to certain sources of income which in aggregate guarantees the subsistence and provides social security for the extended family as a whole” (1981, 42). This division of labor has revitalized the ideal of lineage solidarity and the extended family. It may also have lessened pressures to keep up alliances with lineages in other territories, thus involuting the orientation toward agnation. Another ideal that can be more readily realized with the new wealth is large family size—wealthy men marry more wives and can support more children.

The ideals of manly autonomy and tribal independence persist in resistance to government attempts to impose restrictions and curtail the Bedouins’ freedom to live their own lives and run their own affairs. Although after military rule ended in the late 1950s administration of the Western Desert province was outwardly like that of any other, with a few modifications to accommodate tribal organization (Mohsen 1975, 74), in practice the province simply cannot be run the same way. For example, Bedouins vote on the basis of tribal affiliations in electing their representatives to the national parliament. And young men still try to avoid conscription into the Egyptian army by escaping to Libya or into the desert with the herds. Most disputes are settled by customary law. In the case of serious crimes such as homicides, which cannot be kept from the authorities, the judgments of the state courts are not considered valid. Furthermore, since the Bedouins look to achieve a culprit’s quick release so they can settle matters according to customary law, they are often uncooperative in the courts. Wittingly or unwittingly, most people live outside the law, smuggling, crossing closed borders, carrying unlicensed firearms, avoiding conscription, not registering births, not having identity papers, evading taxes, and taking justice into their own hands. Arrests and jailings carry no stigma for the Bedouins; rather, they occasion self-righteous curses of the government agents responsible.

Nevertheless, more subtle processes linked to the persistence of old ideals and values in new circumstances have begun to transform the Bedouins’ everyday existence. Women have been particularly affected. In the camp and household, the worlds of men and women have become more separate. Although sexual segregation seems always to have characterized Bedouin social life to some extent, it has ossified with the move from tents to houses. In the tents, a blanket suspended in the middle of the tent separated male and female domains when men other than close kin were present. The blankets—unlike walls—were both temporary and permeable, allowing the flow of conversation and information. Now, with each room housing one woman and her children, it has become customary to build a separate men’s room (marbūʿa or manẓara) for receiving guests.

The shift from subsistence to market reliance has altered the extent to which men’s traditional control over productive resources allows them to control women. Women may never have owned or even controlled resources, but women were needed to extract a livelihood from them, and men and women contributed complementary skills to the subsistence economy. This balance has been undermined. In the traditional division of labor, men cared for the sheep, sowed and harvested the grain, and engaged in limited trade. Women were responsible for the household, which involved not just cooking and childcare but also grinding grain, milking and processing milk, getting water (often from distant wells), gathering brush for the cooking fires (arduous because of the primitive adze the women use and the long distances they must travel with heavy loads), and weaving tents and blankets. Peters (1965, 137–38) makes much of the interdependence of the men’s and women’s spheres and the rights conferred on women by control over their special tasks in the traditional economy of the Cyrenaican Bedouins. However, as women’s work has become peripheralized, these rights may have diminished. Housing and furnishings are now bought with cash, food requires less processing, water is close by, and much cooking is done with kerosene, available through purchase. Women’s work is confined to an increasingly separate and economically devalued domestic sphere. Women have also become profoundly dependent on men, as subsistence is now based on cash rather than on the exploitation of herds and fields, which required the labor of men and women and entitled both to a livelihood.

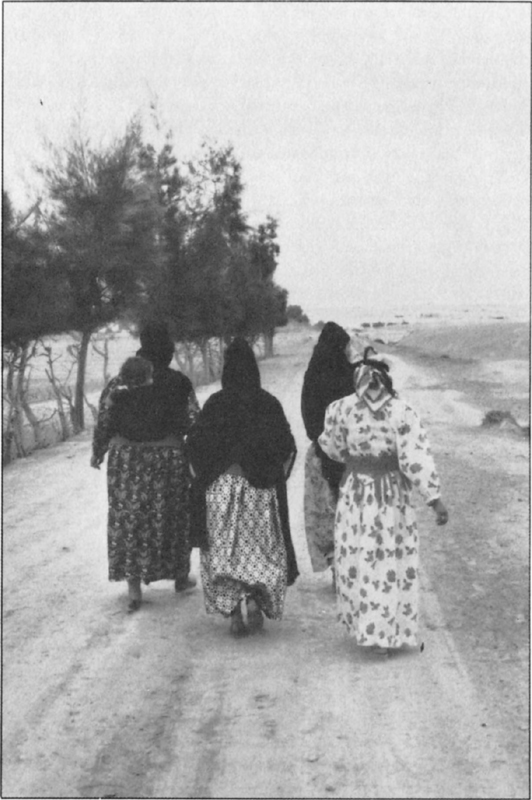

The code of modesty and rules of veiling have a long history, but in the new context of permanent, settled communities they determine to a much greater extent what women do. The likelihood that neighbors will be nonkin or strangers and that they will live in close proximity is greater than it was in the isolated desert camps, where members were usually tied by kinship bonds of one sort or another. In addition, the settlements often have visitors from the wider range of contacts the men develop outside the kin group in the course of their travels and commercial ventures. Because the sexual codes (see chapter 4) require that women avoid male nonkin and strangers, they must now be more vigilant in keeping out of sight, spending more time veiled and confined to the women’s section. This has curbed their freedom of movement.

With sedentarization and new economic options, these codes have restricted women’s social networks and widened the gap between men’s and women’s experiences. Women rarely venture far from their camps except to visit natal kin. Their contacts are limited to kin, husband’s kin, and neighbors. In the past, seasonal migrations brought new neighbors; in settled communities, the set of neighbors tends to become fixed, and opportunities to meet new people and make new friends diminish. In contrast, men have become more oriented to the world outside the camp. Mechanized transport has only increased men’s mobility, and although men still conduct much of their business with kinsmen whom the women also know, they have more contact with outsiders whom the women do not meet. Thus, men and women from the same community live in different social worlds. A household’s men and women now spend less time together, know fewer people in common, and have divergent experiences in daily life. This gap will widen as education becomes more universal, since boys are increasingly enrolled in school but old values keep girls at home.26 Soon men will be literate and women not.

The changes in the relations between men and women and in their relative status and opportunities are neither the result of disaffection with the old system nor an emulation of the mores of imported cultures. They are certainly not the result of government policy. The Bedouins do not experience any jarring sense of discontinuity, although they acknowledge several ways things were different, say, forty years ago. Their sense of continuity may stem from the stability of the underlying principles of their life, which in new contexts created by sedentarization and market economics produce different configurations.

On close inspection, some of the most conspicuous changes prove superficial. Rather than heralding the demise of Bedouin culture and society, they merely demonstrate the Bedouins’ openness to useful innovations and their capacity to absorb new elements into old structures. To take an example, the automobile and pickup truck now popular throughout the Western Desert are status objects in much the same way horses were in the past. Accordingly, the purchase of a new car occasions a sheep sacrifice and a trip to the holyman to get a protective amulet to hang on the rearview mirror. Men are identified by and with their cars. They want to be photographed with them. In young girls’ rhyming ditties, young men are referred to not by name but by the color and make of the cars they drive, as in the following two songs:

Welcome driver of the jeepI’d make you tea with milk if not shamefulyā sawāg ij-jēb tafadׅhdׅhalndīrūlak shāy biḥalīb lū mā ʿēbToyotas when they first appearedbrought life’s light then disappearedTayūtāt awwal mā jaddunjābū nūr l-ʿēn wraddū

Like their animal antecedents, cars are used not just for transport but also for ritual. A bride used to be carried from her natal home to the groom’s home in a litter mounted on a camel, accompanied by men and women riding on horses, donkeys, or whatever could be mustered, all singing, dancing, and firing rifles. Now, although the size of the bridal procession is equally important, its composition has changed; Toyotas, Datsuns, and Peugeots race, the men leaning out of the speeding vehicles firing rifles, the women sitting in the back seats singing traditional songs. Just as the procession used to circle the bridal tent before setting down the new bride, so now the cars careen around the new house or a nearby saint’s tomb.

It is clear that the fundamental organizing principles of social and political life, the ideology and the values, have endured. If the most fashionable weddings are now celebrated with a blaring mīkrōfūn (loudspeaker system) and flashing lights visible for miles against the cloudless night skies, and if the bride is brought in a car with her trousseau following in a pickup truck, weddings are nevertheless held on traditionally auspicious days of the week and celebrated with traditional song and poetry, sheep sacrifices, and feasting. The defloration still takes place in the afternoon, with the proof of virginity triumphantly displayed. Marriages are still linked to the history of marriage alliances between tribal sections, arranged by families, the bride-price negotiated by kinsmen. At marriage the groom does not gain economic independence from his father but brings his wife into the extended household. If women have traded their embroidered leather boots and somber baggy gowns for pink plastic shoes and bright synthetic fabrics, they have not relinquished the black veils they use to demonstrate their modesty and recognize the distance and respect between men and women (see chapter 4).

The most profound changes in the lives of the Awlad ʿAli are a result of new circumstances that have undermined the operation of traditional principles. This is clearest in the towns. The identification of kin with one another is based conceptually on common substance but is intensified by common property and coresidence. Studies of Bedouins who have settled in the city of Marsa Matruh show that residence patterns determined by accident and factors outside their control have significantly weakened the bonds between kin in favor of those between neighbors (ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd 1969, 129). The introduction of education and wage labor may eventually marginalize the pastoral way of life and loosen the hold of the family and tribe as educated Bedouins abandon the life of the desert, the politics of the tribe, and the values of honor and modesty at the center of the Bedouin world. This has not yet come to pass. Although they are becoming settled, the Awlad ʿAli Bedouins are a long way from being peasants. By no means detribalized, they strain under the yoke of political control and prefer to guard what autonomy they have by minimizing dealings with government authorities. In contact with non-Bedouins and the object of numerous government plans, they are still far from being assimilated. As we shall see in the next two chapters, the ideology of honor and modesty so closely associated with nobility of origin has a powerful hold on every Awlad ʿAli individual.