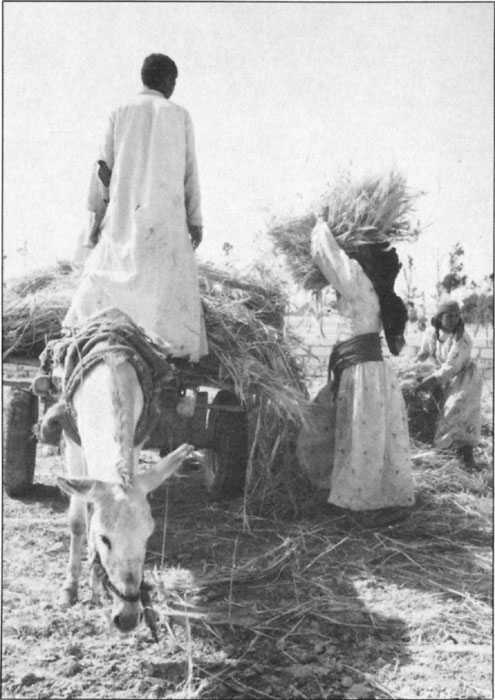

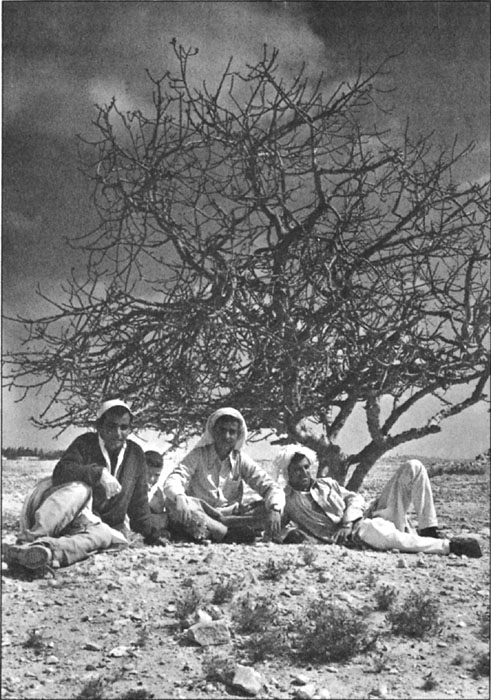

A client family harvesting barley

“Blood,” the central concept in the definition of both Bedouin cultural identity and individual identity is, as I argued in the last chapter, seen as closely tied to moral nature. And Awlad ʿAli believe that morality is what most distinguishes them from and makes them superior to other peoples. At the heart of their moral system are the values of honor and modesty. What these values are and how they shape individual actions, interpretations of others’ actions, and even the life of sentiment must be explored.

This system of morality is especially important to understand because it is the basis for the hierarchical social divisions that exist in the Bedouin social system. Although this social system is often touted as highly egalitarian, and is indeed more egalitarian than many, the realities of power differences are inescapable, especially within the family and lineage. What is intriguing is how, through several ideological means, Awlad ʿAli reconcile their basic value of equality with the hierarchical system by which they live. First, they view as ultimately moral the bases of greater status, control over resources, and such control as people can exercise over others. Individuals must achieve social status by living up to the cultural ideals entailed by the code of honor, in which the supreme value is autonomy. The weak and dependent, who cannot realize many of the ideals of the honor code, can still achieve respect and honor through an alternative code, the modesty code. Second, Awlad ʿAli mediate the contradiction between the ideals of equality and the realities of hierarchy by considering relations of inequality not antagonistic but complementary. They invest independence with responsibility and a set of obligations and dependency with the dignity of choice.

Autonomy or freedom is the standard by which status is measured and social hierarchy determined. It is the consistent element shaping the Bedouin ideology of social life, in which equality is nothing other than equality of autonomy—that is, equality of freedom from domination by or dependency on others. This principle is clear in Bedouin political organization, the segmentary lineage model. Although anthropologists disagree about many other aspects of this system, there is consensus that the system has as its central feature the maximization of unit autonomy (Eickelman 1981; Lancaster 1981; Meeker 1979). Each tribal segment is theoretically equal to every other through opposition. No leader is given authority over the whole confederation of tribal segments, and there are no offices or titles, although there is informal leadership at various levels of segmentation. The value of political autonomy to Awlad ʿAli is even borne out by their continuing resistance, described in chapter 2, to the imposition of state authority, first by the colonial powers and later by the Egyptian government.

The relationship between autonomy and hierarchy is manifested in the broadest social division in the Western Desert, between the Saʿādi tribes, the true Awlad ʿAli, and their traditional client tribes, the Mrābṭīn. The Saʿādi are known as the “free” (ḥurr) tribes, and the word mrābiṭ means “tied”—in this case, tied by obligations of clientage. In the past the Mrābṭīn paid tribute to their Awlad ʿAli patrons, had no tribal territorial rights, and depended on their patrons for the right to use land, wells, and pastures. Although the Mrābṭīn are now independent, able to own land, and no longer paying tribute, the distinction of freedom remains a source of social differentiation because of the moral implications of their ancestry.

Despite the rhetoric regarding the jural equivalence and equality of agnates, tremendous inequalities of status and authority exist within the lineage or tribe as well. These amount to differences in degree of autonomy and are linked, like the distinction between the Saʿādi and Mrābṭīn, to control of resources. The primary distinction is between elders and juniors, involving primarily a differential authority to make decisions. Lineage elders control resources such as tribally owned wells and land. (Livestock is individually owned and is a separate matter.) Senior men make decisions and arrange marriages for junior men. In fact, this relationship is modeled on the extended family, where the father and his brothers (paternal uncles) have authority over sons and nephews. By extension, all older men, as important figures in their own lineages, are deferred to by younger men, who are less important. Junior members serve senior men and sit quietly on the fringes, listening but rarely speaking at gatherings.

Within the family itself, the inequality of patriarch and dependents—in the nuclear family, the man and his wife and children (who are known collectively as his washūn)—is similarly an inequality in relative independence. The family, as I will discuss in the next section, is the prototype of hierarchical relationships. The patriarch controls resources; his dependents are weaker, younger, and control no resources independently. But other relationships within the family are also unequal, for instance that between older and younger siblings, older siblings having precedence. The relationship of inequality between the sexes is usually a function of the familial relationships obtaining between them. Fathers have authority over daughters, as over sons. Older brothers have authority over younger sisters, although, as children, older sisters care for younger brothers and can order them around.

Familial relationships alone do not determine relationships of inequality between the sexes, however. Women are always dependents, as the most common term of reference for women, wliyya (under the protection), indicates. The hierarchical relationship between male and female in general is somewhat independent of particular roles (see chapter 4). For example, advantages of age and responsibility for younger siblings are erased in the case of older sisters and younger brothers. As adults, even younger brothers are responsible for their older sisters and have authority over them. Similarly, the relationship between mother and son, in which initially the mother is all-powerful, controlling access to food and other resources and having the authority to tell sons what to do, equalizes with time. Husband and wife, although both adults and ideally from tribes and lineages of equal standing, are also never equal. There may be severe limits on the husband’s ability to impose his will on his wife, yet she remains dependent and subordinate.

Among Awlad ʿAli, the fundamental contradiction between the ideals of independence and autonomy and the realities of unequal status is mediated by a conceptual device: all relations of inequality are conceived in the idiom of relations of inequality within the family. Since an idiom functions to suggest a possibly obscure relationship through analogy to a well-known relationship, this analogy with the family rhetorically or metaphorically transfers the qualities believed to inhere in family relations to those between persons outside the family.1

The familial idiom downplays the potential conflict in relations of inequality by suggesting something other than simple domination versus subordination. It replaces opposition with complementarity, with the forceful notions of unity and identity, emphasizing the bonds between family members: love and identity. Even more important, the familial idiom suggests that the powerful have obligations and responsibilities to protect and care for the weak. The weaker members, epitomized by the helpless infant, and by extension all children, are dependent on the strong. This responsibility of the strong is, in the familial idiom, motivated not only by a sense of duty but also by concern and affection. Thus, inherent in the division between weak and strong is a unity of affection and mutual concern. The key terms of this rationale legitimizing inequality are dependency and responsibility, embedded within a moral order.

Two specific family relationships provide the models for this metaphorical extension: father/son and elder brother/younger brother. In the case of the relationship between the Saʿādis and the Mrābṭīn, the model is that of brotherhood. Each Mrābiṭ tribe was tied to a particular Saʿādi tribe or segment in a relationship of khuwwa (brotherhood). In return for paying tribute to his Saʿādi “brother,” the Mrābiṭ was entitled to his protection. Because only Saʿādis bore arms or fought, this arrangement allowed the Mrābṭīn to go about their business as herders and farmers without fear of harassment by other tribes. Saʿādi tribal patrons were also responsible for representing their Mrābiṭ clients in disputes. By likening the relationship to that of brothers, the exploitative connotations of Saʿādi dominance were de-emphasized and the protectiveness and mutuality of the relationship highlighted. At the same time, this model suggests the fixed relations between the two groups. Just as with elder and younger brothers, there can never be any reversal of the hierarchical relationship between the two through succession.

The father/son family relationship provides the model for other relations of inequality, including that between lineage elders and juniors and that between patrons and clients. Lineage elders are all known by one of two terms for “father’s brother,” unless they are of the next older generation, in which case they are referred to as “grandfather” (jadd). The linguistic distinction sometimes made in the case of elders is between actual father’s brother (sīd) and other paternal relatives (ʿamm). Like fathers, although to a lesser degree, these people are responsible for providing their descendants with access to lineage resources and the wherewithal to marry. Lineage juniors contribute their labor, as this maintains and increases the patrimony which they will some day inherit. Like sons, lineage juniors will eventually succeed their elders and rise to positions of responsibility.

Although client tribes are no longer bound to free tribes, in the Western Desert individuals or households still attach themselves to wealthy patron families as clients. Patron/client relations, which are like family relations in many ways, share elements of both the father/son and elder brother/younger brother relationships. Like father and son, the patron is responsible for his clients who in turn are dependent on him for the basic necessities of life and provide him with both political support and labor. Yet, like brothers, clients cannot succeed their patrons, despite an increasing involvement in the economic and social affairs of the patron family through which they derive their financial support and in which they share, to the extent that they are able, through partnerships.

The individual client, often a younger man of a poor lineage who has no resources, may be accompanied by his dependents or, more often, he marries and establishes a family once he has become a client. His wife, although primarily in charge of running his household, also performs some services for the women of the patron’s household, and she too is considered a client. The men usually herd sheep for the patron and do odd jobs as required, including building houses and corrals, planting and harvesting barley, and so forth. They stand by their patrons as dependents and supporters in political confrontations. They appear at every large gathering and, along with the sons and nephews, serve guests. Adult male clients take responsibility for greeting guests and watching the patron’s house and may even sleep in the men’s guest room when their patrons are absent.

Patrons provide a means of support for clients, giving them a house, a room in a house, or sometimes a tent; money for food; clothing at special occasions; and usually the means (bridewealth) to marry. They often enter into partnerships with their clients, for example, providing sheep for the clients to care for, receiving in return a fraction of the herd. Alternatively, a patron might buy one or two cows, which the client cares for and feeds, and get in exchange the milk as well as part of the profit when the cows are sold.

A distinctive moral quality of reciprocal obligation and affection characterizes these relationships of inequality, whether within the family or merely conceptualized in the familial idiom. Thus, Bedouins assert, these are relations not of domination and subordination but of protection and dependency. The analogy with families also suggests that the differential control over property and people is not arbitrary or the result of force but is based on the greater competence and abilities of adults and the “natural” dependency of the helpless child who needs care. This construct, of course, masks the arbitrary control over resources that allows one group to be autonomous and forces the other into a position of dependency, creating a differentiation that the Bedouins then use to validate their various social statuses.

Those who would have social precedence have more than just a responsibility to care for dependents. In Bedouin ideology, the tension between the ideals of equality and independence on the one hand and the reality of status differentials on the other is mediated through the notion that authority derives neither from the use of force nor from ascribed position, but from moral worthiness. Hierarchy is legitimated through beliefs about the disparate possession of certain virtues or moral attributes. Furthermore, Bedouins act as though authority must be earned. Because authority is achieved, it can also be lost. This is where the analogy to kinship breaks down. In the family, the roles of provider and dependent and the prerogatives and duties associated with each are more or less fixed or ascribed; certainly the positions of family members are unchangeable. But in social life at large there is more flexibility and room for achievement.

Individuals must earn the respect on which their positions rest through the embodiment of their society’s moral ideals. Although the regularities of status distinction expressed in principles of the precedence of genealogy, greater age and wealth, and gender might seem to contradict any notion of achievement, Awlad ʿAli view these principles as being generally associated with, and hence rough indices of, the moral virtues described below. Insofar as persons demonstrate these virtues, they are entitled to the respect that validates, if not establishes, the social precedence and authority generally associated with these principles. But, as I will illustrate, the principles themselves are not sufficient to determine status. In other words, greater age or wealth, better genealogy or ancestry, or even gender does not necessarily guarantee greater authority or social precedence.

The ideals or moral virtues of Bedouin society together constitute what I refer to as the Bedouin code of honor. The honor code is, despite (or perhaps because of) the tremendous amount of anthropological attention devoted to it in studies of both Christian and Muslim circum-Mediterranean cultures, strangely difficult to define.2 Friedrich (1977, 284) provides the most attractive way of thinking about it: “Honor is a code for both interpretation and action: in other words, with both cognitive and pragmatic components.” In its first aspect it is “a system of symbols, values, and definitions in terms of which phenomena are conceptualized and interpreted.” In the second, honor guides and motivates acts “organized in terms of categories, rules, and processes that are, to a significant degree, specific to a given culture. . . . ” Friedrich then goes on to outline the structure of Iliadic honor as a “network” of propositions about honor and “honor-linked values” that he considers specific to Homeric Greek culture.

The values of the Bedouin honor complex are not those of the Iliad, nor those of the complex as found in Spain, Sicily, Algeria, or any other Mediterranean society. The critical term in the Awlad ʿAli honor code is aṣl (ancestry/origin/nobility), a term expressive of a range of ideas. As I discussed in chapter 2, it is the basis for the proud differentiation of Bedouin from non-Bedouin. Drawing on the genealogical notion of roots, or the pure and illustrious bloodline, it also implies the moral character believed to be passed on through this line. Thus aṣl is the primary metaphor for virtue or honor.

What is the Awlad ʿAli network of honor-linked values? And how do these values legitimate greater social standing? First, there are the values of generosity, honesty, sincerity, loyalty to friends, and keeping one’s word, all implied in the term usually translated as honor (sharaf). Even more important, however, is the complex of values associated with independence. Being free (ḥurr) implies several qualities, including the strength to stand alone and freedom from domination. This freedom with regard to other people is won through tough assertiveness, fearlessness, and pride, whereas with regard to needs and passions, it is won through self-control. Failings or weaknesses in any of these areas disqualify one for positions of responsibility and respect and put one in a position of dependency or vulnerability to domination by others.

Applied in numerous contexts to distinguish both individual Bedouins and families and lineages, the qualities associated with aṣl are apparent in the way the differences between Saʿādis and Mrābṭīn are characterized. Technically, only the Saʿādi tribes are known as the Awlad ʿAli, or sons of ʿAli. Their ability to trace their genealogical connection to a single eponymous ancestor is a matter of pride, as is the corresponding ability to find a relationship of kinship between any two individuals, lineages, segments, or tribes. By contrast, the Mrābṭīn are considered an unrelated conglomeration of tribes with no overarching genealogical unity. This absence of genealogy implies lesser moral worth.3 Saʿādis describe Mrābṭīn as lacking in the virtues of honor, such as generosity (Mrābṭīn are said to be stingy), ability to fight and resolve disputes, and efficaciousness in the world (Mrābṭīn are described as “all talk,” or as “a pot that boils and boils”). In fact, even Mrābṭīn view themselves as inferior to the Saʿādi. One Mrābiṭ explained to me, “We are weak, humble. It is not a matter of money, because some Mrābṭīn are wealthy. But a Siʿdāwi [sing.] has ‘standing,’ pride, boldness, and goodness. He has a ‘face in front of people’ [respect, reputation].”

Sometimes Mrābiṭ individuals are recognized as noble, as displaying the moral qualities associated with aṣl; but people explained that in such cases, if one probed, one always discovered the existence of some Saʿādi blood in the family line—a Saʿādi maternal uncle or grandfather, perhaps—which indicates how closely the Bedouins associate blood and character.

The ideals of Bedouin manhood highlight the importance of freedom to aṣl. One man explained, “A real man stands alone and fears nothing. He is like a falcon [shahīn]. A falcon flies alone. If there are two in the same territory, one must kill the other.” Freedom and fearlessness are coupled in another word for falcon, “free bird” (ṭēr ḥurr). The courage of the warrior ethic applies not just to matters of war or fighting, as described in the contrast between Bedouin and Egyptian and between Saʿādi and Mrābiṭ, but to the interactions of everyday life. The “real man” is not afraid of being alone at night, despite the risk of confrontation with wild animals and spirits (ʿafārīt) in the open desert where there are no lights and few humans. Fear of anyone or anything implies that it has control over one.

A powerful person is described in terms of gadr (power), from the root meaning capability or ability. Capability as such is realized in a number of arenas and has much to do with confrontation with others. Gadr is the particular ability to resist others through equal or greater strength; it depends both on personal courage and assertiveness and on wealth, since generosity and hospitality are means of making others dependent. The quality of challenge and the competition for dominance involved in gadr come out clearly in an amusing incident I witnessed. An older man was sitting with his younger brother. His youngest daughter, a charming and much-loved toddler, wandered in and went to cuddle with her father. Her uncle teased her, threatening to kill her (using the same word used to talk about slaughtering sheep). Her father coached her to throw back the challenge, asking rhetorically, “Yagdar?” which implied both “Is he capable?” and “Does he dare?” This interchange was repeated several times as the little girl, standing close to her father for support, challenged her uncle with emphatic No’s every time he threatened.

Related to such strength are qualities of toughness. Admired men were often described as difficult (waʿr) or tough (jabbār). Large in stature and physically strong, such men assert their will. Women claim, for instance, that “real men” control all their dependents and beat their wives when the wives do stupid things. One woman, whose daughter was about to marry one of the most respected men in the camp, said, “My daughter wants a man whose eyes are open—not someone nice. Girls want someone who will drive them crazy. My daughter doesn’t want to be with someone she can push around, so she can come and go as she pleases. No, she wants someone who will order her around.”

Although her remarks about women’s desires must be taken with a grain of salt, since they were intended to show me (and presumably all the people to whom I would convey her words) what a wonderful and compliant bride her daughter would make, they nevertheless indicate what she believed men wanted to hear about themselves. In general, women share the men’s idealization of the assertive person and the view that such people are the source of order in the community and household. However, there are limits on how much a man should assert his will. Men and women always condemn the excesses of a harsh or volatile husband, and women privately appreciate a certain amount of kindness in a man.

The correspondence between these qualities of assertiveness and the quality of potency, as described by Bourdieu (1979) of a Kabyle man of honor, are striking.4 Bourdieu sees the “rules of honour” as those of the logic of challenge and riposte, in which a challenge both validates an individual’s honor by recognizing him as worth challenging and serves as a “provocation to reply” (Bourdieu 1979, 106). Inability to reply and counter the challenge results in a loss of honor. As he notes, “Evil lies in pusillanimity, in suffering the offence without demanding amends” (Bourdieu 1979, 113). In both the Awlad ʿAli and the Kabyle codes, men of honor share a general orientation toward assertiveness and efficacy.

The final element in the Bedouin network of honor-linked values is self-mastery, one aspect of which is physical stoicism. Bedouins think physical pain and discomfort should be borne without complaint.5 When a youth from our community underwent a serious operation in Cairo, I visited him in the hospital. His non-Bedouin roommates, all of whom had undergone the same operation, remarked on the fact that he had not complained once, whereas they had suffered terribly, moaning and complaining to all who would listen. The young man’s father turned to me with pride, glad that his son had confirmed the Bedouin ideal in practice. It may well be that people disapproved of my continual complaints about my flea bites for the same reason. They always told me to try to be tougher.

The stoic acceptance of emotional pain is another aspect of self-mastery. To weep is a sign of weakness, so men of aṣl do not cry, regardless of the intensity of their grief. In describing his reaction to the death of a favorite aunt, one young man said, “Men don’t cry. I got a terrible headache because the death was so hard on me [ṣaʿbat ʿalayy].” Mastery of needs for and passions toward others—the true sources of that dependency so antithetical to honor—seems to be related to the development of ʿagl, a complex concept, fundamental in most Muslim cultures, from Morocco to Afghanistan,6 that can be glossed as reason or social sense. It is said that angels have only ʿagl, whereas Adam was a combination of ʿagl and passion, or carnal appetite (shahwa). Animals are at the other extreme from angels, having no ʿagl.

Children are born with almost no ʿagl but develop it in the process of maturing,7 as is clear in the Awlad ʿAli description of the four stages in the male life cycle. First is childhood, a time of no responsibility when a boy merely gratifies his needs and plays. On reaching majority (sinn ir-rushd), when fasting and praying begin in earnest and a man becomes responsible for blood-payments of his tribe, he begins the years of youth (shabāb). The Bedouins have mixed feelings about this period, which lasts until about age forty. These are the great years of love and life; yet because he is governed by his passions, a man is considered flawed in religious and social terms. At forty, however, he begins to be “wise” or “reasonable” (ʿāgil). He is said to know right from wrong and to be complete. The last stage, old age (shēkhūkha), can be merely a continuation of the period of being ʿāgil, unless senility sets in. ʿAgl, then, is an aspect of maturity.

The value of self-control, or the possession of ʿagl, is especially apparent in the political realm. The most respected men in the Western Desert are those called on to mediate disputes. The person who does not anger easily, who is even-tempered and patient, dispassionate and fair, is “asked for in tribal hearings” (maṭlūb fil-miʿād). Mediators are usually drawn from the ranks of the leaders of the smallest sociopolitical units, the byūt or residential sections, and referred to by the term ʿawāgil, the plural of the adjectival form of ʿagl.8 Reason and age are embedded in this title, since most section leaders are the most senior men in a group of agnates.

Only the insane and the dim-witted do not develop ʿagl over time; like children, they have no social sense, showing no self-control in eating, drinking, defecating, or sometimes in the satisfaction of sexual needs. Although they are tolerated in Bedouin society and are not outcasts, both are disqualified from participating as equal members of society. They remain dependents all their lives, usually under the care of kin. Because their lack of ʿagl or social sense prevents them from conforming to the society’s rules and cultural ideals, they are without honor.

The relationship between certain ascribed characteristics or principles on which hierarchy might appear to be based (such as age, wealth, and gender) and the actual statuses of individuals can now be fleshed out. It is not age per se that entitles one to authority over others or to higher social standing, as the positions of idiots and the insane demonstrates. Age tends to go with increasing self-mastery as well as responsibility for others. Age also brings increasing freedom from those on whom one depends or who have authority over one, because as time passes they die. Wealth provides the means for gadr (power) in that it allows a person to be generous, to host lavishly, to reciprocate all gifts (hence, to meet all challenges), and finally, to support many dependents. A wealthy man can support more wives, more children, and more clients, thus increasing the number of people over whom he has authority or who owe him deference. Gender affects the extent to which an individual can control property and people and, consequently, the degree to which he or she can embody the ideals of independence.

If individuals fail to embody the honor-linked values just outlined, they lose the standing appropriate to their age, level of wealth, gender, or even genealogical precedence (in the case of Saʿādis, for instance, or people from illustrious lineages). Specifically, they lose the respect on which their authority is based. Acts of cowardice, inability to stand up to opponents, failure to reciprocate gifts, succumbing to pain, miserliness—all are dishonorable and lead to a loss of respect. Inability to control desire for women is particularly threatening to a man’s honor. Conversely, exemplary behavior on the part of any individual, of whatever age, level of wealth, or gender, is recognized and rewarded with respect.

The following actual cases illustrate effectively how failure to demonstrate the virtues of honor can result in a loss of social standing. The first concerns Zarība, a distinguished-looking old man in his sixties who had been one of the most respected and wealthy men in the area. He had inherited a large herd from his father, but over the course of ten years he had begun to squander his wealth. People said he was attracted to and bought for his family any useless new thing that appeared in the markets. He acted inappropriately in other contexts as well. For instance, one day he appeared at the house of an old woman he had known since his youth, complaining that his clothes were dirty and begging her to wash them for him. She agreed, but wondered what he was to wear in the meantime. He suggested that he would wear one of her dresses. The one she happened to pick out was fairly translucent. He kept laughing and commenting on how his genitals were showing. People interpreted his bizarre and unseemly behavior as a sign that he had lost his mind. Most important, however, he began to chase women, selling his property, including sheep, to buy gifts to attract these women and convince them to marry him. Especially because of his desire for these women, he became the laughingstock of the area.

Zarība’s case illustrates the priority of honorable behavior over ascribed positions based either on age or wealth. He violated the code of honor by failing to control his passions; he chased women and was shameless in that he made obscene comments. By being irresponsible toward his family, and thus not fulfilling his role as provider, he violated the pact assuring that the dominant provide for the weak. Although older than most of the men with whom he associated, he no longer received their respect.

The man who needs women is called either a fool (habal) or a donkey (ḥmār), both epithets alluding to an absence of ʿagl. The bestial insult is applied to the man who seems not in control of his sexual appetites. Men who took many wives, whether wealthy (as was one man reputed to have married thirty-two women during his lifetime) or poor (as was another who took whatever money came his way to pay the bride-price for another wife, even though he could not feed or clothe the ones he had) were often called donkeys. The term was also applied to adulterers and men who frequented prostitutes. These men were described as bitāʿ ṣabāya, literally, belonging to women. Depending on the consequences of their acts they were either denounced or merely ridiculed. Disapproval was severe when the men neglected their familial responsibilities, failing to provide adequately for their dependents. When it did not jeopardize the welfare of dependents, the same behavior merely exposed the men to ridicule. Behind their backs, women described such men’s interests in obscene gestures and bawdy jokes; they considered them fools for being driven by sexual desire.

Greater contempt is reserved for the man who, not simply a slave to his passions, compromises his independence by admitting dependence on a particular woman. This sign of weakness permits the proper power relations between the sexes to be reversed. One old woman told me, “When a man is really something [manly], he pays no heed to women.” “A man who listens to his wife when she tells him what to do is a fool,” said a young woman. Another old woman explained, “Anyone who follows a woman is not a man. He is good for nothing.” Many agreed, adding, “If a man is a fool, a woman rides him like a donkey.” If the women feel this way, the men feel all the more strongly about it.

A man forfeits control and loses honor either through a general lack of assertiveness vis-à-vis women—almost a personality defect—or through an excessive attachment to one woman, culminating in a fear of losing or alienating her. The unassertive man is described as flabby, flaccid, or nice—a most pathetic character. One such man was criticized for not daring to scold his wife and for being afraid to demand his meals when he came home. He always called his daughters if he wanted anything because his wife wouldn’t budge. She visited around the camp all day, and he never questioned her.

Even if not flabby as a personality—in fact upholding most of the values of the honor code—a man can seem foolish, and hence be dishonored, if he becomes overly attached to a woman. The flavor of kin reactions to the violations of the ideals of independence can best be imparted through describing the events surrounding one such violation.

Rashīd, a man in his early forties from an important family, took a second wife fifteen or twenty years his junior. For the first two weeks after his wedding, Rashīd spent every night with his new bride, who had been placed in a household separate from that of his first wife, the mother of his six children. Although it is customary to spend the first week exclusively with the new bride, he did seem to be delaying the start of the proper rotation schedule. Even when he finally returned to spending nights with his first wife, he did not carry through with the expected alternation of nights but spent most nights with the new bride. People in the community began to criticize him mildly, commenting that his children were beginning to miss him.

One day, after a growing unhappiness (unknown to all but the women who shared her household), his bride suddenly ran away, seeking refuge in the house of some neighbors belonging to a saintly tribe. The other woman in her household, Rashīd’s paternal first cousin and his elder brother’s wife, spotted her just as she reached the neighbor’s house. She ran to inform Rashīd, who began to pursue his bride but then stopped, presumably realizing the utter impropriety of such a move. Instead he asked his cousin to go talk to her, to try to persuade her to return. With tremendous embarrassment she went, entering a house she had never visited (violating social convention), and was refused by the bride.

Rashīd then set off in his truck to his bride’s brother’s house, some twenty kilometers away, to inform her family. (She was under the guardianship of her brother, since her father had divorced her mother, remarried, and moved to a separate household two hundred kilometers away.) Her mother and brother immediately came to get her and took her home with them. Rashīd spent the night alone. People in the household reported that he did not sleep; he moped around.

Rashīd’s elder brother, the family spokesman and its most respected member, was informed of these events the next day when he returned from a trip. He consulted at length with Rashīd’s other brothers and cousins in the camp. These men all thought it best that Rashīd divorce her for insulting them: she had compromised Rashīd’s pride, which reflected on them as kinsmen; they wanted to turn the tables and make her family look bad. They preferred to leave the bride at her home and, as an insult, not even demand the return of the bridewealth, to which they would have been entitled because she wished the divorce. But Rashīd wanted her back, so a few days later his elder brother went to negotiate the bride’s return, furious for having to endure the humiliation of begging.

He was not the only angry one. One of Rashīd’s cousins later commented, “Rashīd is an idiot. You don’t go chasing a woman when she leaves!” Had he beaten her or given her some cause, that would have been better. Rashīd’s mother, an outspoken old woman, ranted, “He’s an idiot [habal]. I never heard of such a fool. The woman goes and throws herself at the Mrābṭīn.9 If you are a man you don’t go after her, for God’s sake. Idiot! I’ve never seen such a thing. What you do is leave the girl there—don’t even tell her family she has run away. Let them hear in the marketplace that their daughter is at the house of strangers. [This would constitute a scandal, not only because people would be talking about their kinswoman in public but also because suspicions would arise about her chastity.] He’s no man!” The other men in the family were unanimous in their criticism of Rashīd’s wish to take her back—one was so disturbed that he avoided the household for several months after the bride did return. Even Rashīd’s cousin, in whom he had confided and who was more sympathetic, commented as she watched him soon after the bride’s return, “He’s an idiot. He can hardly believe she’s back. He’s so happy.” She had earlier scolded Rashīd’s nephew for looking forlorn and sympathizing with his uncle, saying, “You get upset over a woman? Don’t ever get upset over a woman. Thank God we have men and money. There are lots of women. You can always get another.” She followed this with a song to the same effect:

Money we have aplentyif she leaves, we’ll get someone else . . .il-māl ʿindinā mayjūdin rāḥat njībū ghērhā . . .

For a few weeks after the bride’s return, Rashīd did not visit his first wife. Men and women in the community began to comment again. However, most of them did not know that the bride had discovered an amulet under her bed, which Rashīd had finally confessed to placing there, to prevent her from leaving again. A few members of the household were privy to this extraordinarily well-kept secret, but they were so embarrassed (for Rashīd’s sake) about his dependence that they did not want anyone to know.

The public disapprobation that followed from this man’s failure to realize the ideals of tough, assertive independence resulted in the community’s loss of respect. By relinquishing control over his feelings, he allowed himself to be controlled by another person. His attachment to his bride was interpreted as a weakness of character: his mother, brothers, and cousins criticized him as lacking in ʿagl, and even the children, his nephews and nieces, all told me that they no longer feared him. Through this episode Rashīd lost the status appropriate to his age, that of the man of honor who is master of himself and others—a status that he had until then held.

These cases illustrate how important acting in terms of the moral virtues of the honor code is for achieving or legitimizing a higher place in the social hierarchy. Persons in such positions have a greater responsibility to uphold the cultural ideals, and it is their embodiment of the ideals that justifies their responsibility for, and control over, others. It is perhaps ironic that greater control entails more stringent requirements of conformity, rather than license to break the social rules, but this seems to be characteristic of what Bourdieu calls “elementary forms of domination.” He notes of the Kabyle that “the ‘great’ are those who can least afford to take liberties with the official norms, and that the price to be paid for their outstanding value is outstanding conformity to the values of the group” (1977, 193). Bourdieu links moral virtue to power, writing that “the system is such that the dominant agents have a vested interest in virtue; . . . they must have the ‘virtues’ of their power because the only basis of their power is ‘virtue’” (1977, 194).

Where individuals value their independence and believe in equality, those who exercise authority over others enjoy a precarious status. In Bedouin society, social precedence or power depends not on force but on demonstration of the moral virtues that win respect from others. Persons in positions of power are said to have social standing (gīma), which is recognized by the respect paid them. To win the respect of others, in particular dependents, such persons must adhere to the ideals of honor, provide for and protect their dependents, and be fair, taking no undue advantage of their positions. They must assert their authority gingerly lest it so compromise their dependents’ autonomy that it provoke rebellion and be exposed as a sham.

Because those in authority are expected to treat their dependents, even children, with some respect, they must draw as little attention as possible to the inequality of their relationships. Euphemisms that obscure the nature of such relationships abound. For example, Saʿādi individuals do not like to call Mrābiṭ associates Mrābṭīn in their presence. My host corrected me once when I referred to his shepherds by the technical word for shepherd, saying, “We prefer to call them ‘people of the sheep’ [hal il-ghanam]. It sounds nicer.” The use of fictive kin terms serves the same function of masking relations of inequality, as for example in the case of patrons and clients.

Those in authority are also expected to respect their dependents’ dignity by minimizing open assertion of their power over them. Because the provider’s position requires dependents, he risks losing his power base if he alienates them. When a superior publicly orders, insults, or beats a dependent, he invites the rebellion that would undermine his position. Such moments are fraught with tension, as the dependent might feel the need to respond to a public humiliation to preserve his dignity or honor. Indeed, refusal to comply with an unreasonable order, or an order given in a compromising way, reflects well on the dependent and undercuts the authority of the person who gave it.

Tyranny is never tolerated for long. Most dependents wield sanctions that check the power of their providers. Anyone can appeal to a mediator to intervene on his or her behalf, and more radical solutions are open to all but young children. Clients can simply leave an unreasonable patron and attach themselves to a new one. Young men can always escape the tyranny of a father or paternal uncle by leaving to join maternal relatives or, if they have them, affines, or even to become clients to some other family. For the last twenty years or so, young men could go to Libya to find work.

Younger brothers commonly get out from under difficult elder brothers by splitting off from them, demanding their share of the patrimony and setting up separate households. The dynamic is clear in the case of the four brothers who constituted the core of the camp in which I lived. Two had split off and lived in separate households. Another two still shared property, herds, and expenses. While I was there, tensions began to develop. Although the elder brother was more important in the community at large, and the younger brother was slightly irresponsible and less intelligent, for the most part they worked various enterprises jointly and without friction. The younger brother deferred to his older brother and usually executed his decisions.

But one day the tensions surfaced. The elder brother came home at midday in a bad mood only to find that no one had prepared him lunch. He went to one of his wives and scolded her for not having prepared any lunch, asserting that his children had complained that they were hungry. He accused her of trying to starve his children and threatened to beat her. His younger brother tried to intervene, but the elder brother then turned on him, calling him names. Accusing him of being lazy (because he had failed to follow through on a promise involving care of the sheep that day), he then asked why the younger brother let his wife get away with sitting in her room when there was plenty of work to be done around the household. Then he went off toward his other wife carrying a big stick and yelling.

The younger brother was furious and set off to get their mother. The matriarch, accompanied by another of her sons, arrived and conferred at length with the quarreling men. The younger son wished to split off from his elder brother’s household; the other brother scolded him for being so sensitive about a few words, reminding him that this was his elder brother, from whom even a beating should not matter. His mother disapproved of splitting up the households. Eventually everyone calmed down. But it is likely that a few more incidents such as that will eventually lead the younger brother to demand a separate household.

Even a woman can resist a tyrannical husband by leaving for her natal home “angry” (mughtāẓa). This is the approved response to abuse, and it forces the husband or his representatives to face the scolding of the woman’s kin and, sometimes, to appease her with gifts. Women have less recourse against tyrannical fathers or guardians, but various informal means to resist the imposition of unwanted decisions do exist. As a last resort there is always suicide, and I heard of a number of both young men and women who committed suicide in desperate resistance to their fathers’ decisions, especially regarding marriage. One old woman’s tale illustrates the extent to which force can be resisted, even by women. Nāfla reminisced:

My first marriage was to my paternal cousin [ibn ʿamm]. He was from the same camp. One day the men came over to our tent. I saw the tent full of men and wondered why. I heard they were coming to ask for my hand [yukhulṭū fiyya]. I went and stood at the edge of the tent and called out, “If you’re planning to do anything, stop. I don’t want it.” Well, they went ahead anyway, and every day I would cry and say that I did not want to marry him. I was young, perhaps fourteen. When they began drumming and singing, everyone assured me that it was in celebration of another cousin’s wedding, so I sang and danced along with them. This went on for days. Then on the day of the wedding my aunt and another relative caught me in the tent and suddenly closed it and took out the washbasin. They wanted to bathe me. I screamed. I screamed and screamed; every time they held a pitcher of water to wash me with, I knocked it out of their hands.His relatives came with camels and dragged me into the litter and took me to his tent. I screamed and screamed when he came into the tent in the afternoon [for the defloration]. Then at night, I hid among the blankets. Look as they might, they couldn’t find me. My father was furious. After a few days he insisted I had to stay in my tent with my husband. As soon as he left, I ran off and hid behind the tent in which the groom’s sister stayed. I made her promise not to tell anyone I was there and slept there.But they made me go back. That night, my father stood guard nearby with his gun. Every time I started to leave the tent, he would take a puff on his cigarette so I could see that he was still there. Finally I rolled myself up in the straw mat. When the groom came, he looked and looked but could not find me.Finally I went back to my family’s household. I pretended to be possessed. I tensed my body, rolled my eyes, and everyone rushed around, brought me incense and prayed for me. They brought the healer [or holyman, fgīh], who blamed the unwanted marriage. Then they decided that perhaps I was too young and that I should not be forced to return to my husband. I came out of my seizure, and they were so grateful that they forced my husband’s family to grant a divorce. My family returned the bride-price, and I stayed at home.

Nāfla could not oppose her father’s decision directly, but she was nevertheless able to resist his will through indirect means. Like other options for resistance by dependents unfairly treated, abused, or humiliated publicly, her rebellion served as a check on her father’s and, perhaps more important, her paternal uncle’s power.

Supernatural sanctions, which seem to be associated with the weak and with dependents, provide the final check on abuse of authority. Supernatural retribution is believed to follow when the saintly lineages of Mrābṭīn are mistreated, their curses causing death or the downfall of the offender’s lineage. In one Bedouin tale, when a woman denied food to two young girls, she fell ill, and blood appeared on food she cooked—a punishment for mistreating the helpless. Possession, as Nāfla’s tale illustrates, may also be a form of resistance. It seemed that many of the possession cases I heard about were linked to abusive treatment such as wife beating, but unlike Nāfla’s they were not faked.

All these sanctions serve to check the abuse of power by eminent persons who have the resources to be autonomous and to control those who are dependent on them. At the same time, moreover, figures of authority are vulnerable to their dependents because their positions rest on the respect these people are willing to give them.

Most analyses of honor take the perspective of those at the top of the hierarchy who are able to realize the social ideals. Yet it is important to ask how those at the bottom resolve the contradiction between their acceptance of these ideals and their own limited position, which rarely allows them to realize the ideals themselves. The tensions between Bedouin cultural ideals for the individual and the realities of hierarchy are most acute for these people. As Bedouins, they share with their superiors a high regard for autonomy and equality, the values of honor. Individuals of lower status, especially young persons and women, may have aṣl, or noble origins, through their tribal affiliations or merely as Bedouins, in contrast to Egyptians. But as dependents, the extent to which they can realize the ideals of behavior that validate aṣl is limited. Their lack of control over resources handicaps them with regard to the generosity and ability to provide that lie at the heart of power (gadr). By definition, their independence and capacity to stand alone are minimal, and they can assert their wills only in highly circumscribed social situations. Moreover, opposition to those who provide for them and have authority over them is only successful when their superiors’ decisions are clearly unreasonable or their treatment of dependents disrespectful.

One way those at the bottom resolve the contradiction between their positions and the system’s ideals is by appearing to defer to those in authority voluntarily. This situation is merely the obverse of the point made earlier, that a person in authority must earn respect through moral worthiness: the free consent of dependents is essential to the superior’s legitimacy. What is voluntary is by nature free and is thus also a sign of independence. Voluntary deference is therefore the honorable mode of dependency.

The value placed on voluntary submission can be judged from various situations. One young man, in recounting the events that led to his dropping out of school, highlighted the importance of the concept of voluntary submission to the discipline of school. He described how one day his schoolteacher called him and his cousin to the office and threatened to beat them for disrupting a class. The young man responded, “Don’t you dare hit us. You can’t. We are here studying of our own free will. We are not peasants. We have men behind us. You’ll see what will happen if you lay a hand on us.”

He did not return to school for the rest of the year. During the summer, when his older brothers saw the teacher in the local market they threw rocks at him and escaped. This is an extreme example, complicated by the fact that the teacher was an Egyptian and thus, in this young Bedouin’s mind, an inferior sort lacking all the moral virtues, hence with no right to impose his authority. The young man’s outburst implied that whereas perhaps peasants might put up with such treatment, Bedouins would not.

Women are always dependents to some degree. Bedouin ideology holds that they are to be “ruled” by men and should be obedient. Yet, again, as Bedouins with tribal affiliations, they can have aṣl. As with other dependents—for instance, young men—women’s submission is personally demeaning and worthless to their superiors unless perceived as freely given. On several occasions women and girls contrasted Bedouin women with Egyptian or peasant women in terms of the latter’s docility in the face of coercion. For example, in describing a new bride from a peasant area, people said, “She’s from the east. Look, she works so hard, serves her mother-in-law without a word, deals with all that filth and those children [her husband’s father’s]—an Arab [Bedouin] girl would never put up with that. She would refuse.” At the same time, they criticized the husband’s family for wanting a girl of such lowly origins, insinuating that the groom’s mother had only wanted a servant who would not give any trouble.

People pity a woman who seems to obey her husband because she has no choice, either because she comes from an extremely poor family or because she has no male kin who would or could support her if she wished to leave her husband. But they also regard such a woman with some contempt, describing her not only as calm or docile (hādya) but also as pathetic (ghalbāna) and poor (rāgdat rīḥ, literally, “sleeping in the breeze”).

Those who are coerced into obeying are scorned, but those who voluntarily defer are honorable. To understand the nature, meaning, and implications of voluntary deference we must explore the concept of ḥasham. Perhaps one of the most complex concepts in Bedouin culture, it lies at the heart of ideas of the individual in society. Rarely did a day pass without one form or another of this word arising spontaneously in conversation, yet the meaning seemed to shift depending on the context. In the leading dictionary of modern standard Arabic, various words formed from the triliteral root ḥashama are translated by a cluster of words including modesty, shame, and shyness. In its broadest sense, it means propriety. It is dangerous to accept any one of these terms, however, lest we prematurely assume that we understand what the Awlad ʿAli mean.10 As Paul Riesman (1977, 136) points out, regarding a similar concept among the Fulani of Upper Volta, “the existence of a convenient term for a complex entity risks creating the false impression that in knowing the term we know the entity which it designates.”

In any case, dictionary searches to determine cultural meanings are of questionable validity. The controversy provoked by Antoun’s (1968) reliance on dictionary definitions in his classic article on Arab women’s modesty is instructive. Ḥasham is in fact one of the key words on which he bases his analysis. He writes, “Ḥishma refers to bashfulness or self-restraint and iḥtishām to modesty or respect, both related to the triliteral root form that means to cause to blush.” Thus far the definition suffers only from vagueness. He then adds, “But another form of the same root maḥāshim means pudenda. Many Quranic references to modesty and chastity are literally references to the protection of female genitalia” (Antoun 1968, 679). These definitions constitute part of his evidence for interpreting women’s modesty as tied exclusively to sexuality.

Abu-Zahra’s (1970) reply to Antoun’s article is multi-faceted. One part of her criticism focuses on his reliance on lexigraphic explorations of “museum words” either unknown to the “illiterate villagers” he discusses or whose referent varies across Arabic dialects (Abu-Zahra 1970, 1081). Consulting the most definitive Arabic dictionary herself, she turns up no mention of pudenda as a meaning of the word maḥāshim. Furthermore, she cites very different meanings for the words in both Tunisian and Egyptian spoken Arabic. In attempting to understand how the concept of ḥasham informs Awlad ʿAli society, then, the word’s meaning should be sought not in obscure dictionaries of classical Arabic but in everyday usage.

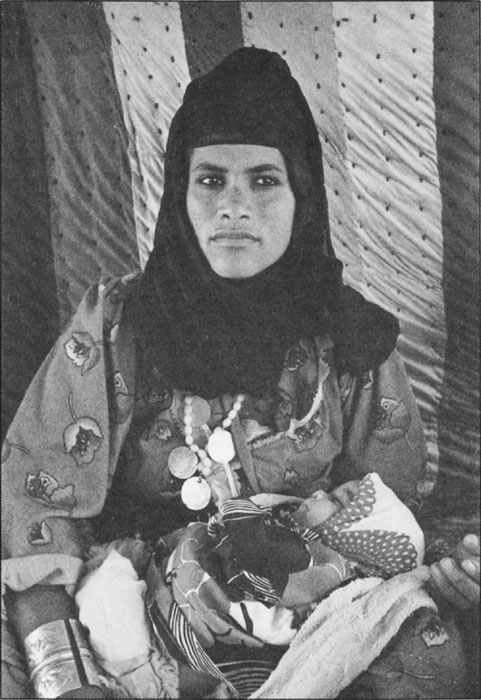

In daily parlance, words from the root ḥashama are used in various grammatical forms, each having a slightly different sense. The two poles of meaning around which usage clusters are those referring to an internal state and those referring to a way of acting; thus, ḥasham involves both feelings of shame in the company of the more powerful and the acts of deference that arise from these feelings. In the first instance, ḥasham is conceptualized as an involuntary experience (we might even call it an emotion); in the second, as a voluntary set of behaviors conforming to the “code of modesty.” The experience is one of discomfort, linked to feelings of shyness, embarrassment, or shame, and the acts are those of the modesty code, a language of formal self-restraint and effacement. The cultural repertoire of such behaviors includes the most extreme and visible acts of veiling and dressing modestly (covering hair, arms, legs, and the outlines of the body) as well as more personal gestures such as downcast eyes, humble but formal posture, and restraint in eating, smoking, talking, laughing, and joking.

Ḥasham is closely tied to the concept of ʿagl, the social sense and self-control of honorable persons. Just as the possession of ʿagl enables persons to control their needs and passions in recognition of the ideals of honor, so it also allows them to perceive the social order and their place within it. Children, who are said not to have much ʿagl, must be taught to taḥashsham (v.); the primary goal of socialization is to teach them to understand social contexts and to act appropriately within them—which means knowing when to taḥashsham. Mothers often scold their children with the imperative, which can be translated as “behave yourself” or “act right” and which implies, “have some shame.”11 The dual connotations of appropriate ways of feeling and voluntary behavior control are apparent here.

The concepts of ḥasham and ʿagl are closely wedded in notions of the ideal woman. The woman who is ʿāgla (reasonable, characterized by ʿagl) is well-behaved; she acts properly in social life, highly attuned to her relative position in all interactions. There is also a spillover into general comportment, which should conform to the behavior appropriate to modesty. People say of a woman who is ʿāgla that she knows when to speak and when to listen. This description draws attention to the fact that she is deferential, since in Bedouin society the superior speaks and the inferior listens. A leader or important person is one said to have the “word” (kilma). The ideal woman is described as having a soft voice (ḥissha wāṭī), not a “long tongue.”

The negative case of the woman who lacks ʿagl or does not taḥashsham can take one of two forms: she can be described either as willful (gāwya) or as slutty (qḥaba). The second aspect refers specifically to sexuality, which will be considered in the next chapter, where I argue that conformity to sexual norms is merely an aspect of deference to those who more closely represent the social ideals. The first, gāwya—from the root qwy, to be strong or powerful—clearly pertains to hierarchical relations. The Bedouins use this particular adjectival form in reference only to females. It means something like “overly strong” and suggests excessive assertiveness. The negative connotations of this sort of assertiveness derive from its inappropriateness for those in positions of dependency or social inferiority. For example, the word is applied to a woman or girl who is contrary or argumentative with her elders, who refuses to do what she is told, talks back, or does things without permission. Grown women who refuse requests or disobey husbands or in-laws are also labeled willful and are perceived as lacking in ḥasham. Those who “talk too much” invite disciplinary action.

Bedouins attribute such disrespectful behavior to improper upbringing, specifically overindulgent treatment. Although mothers threaten and discipline boys as much as girls, they say that girls should be treated with less indulgence lest they become willful, and boys should not be disciplined as much lest they become fearful. Boys should also be indulged, presumably so they will gain a sense of power, rather than weakness, in interactions with others. Women rationalize their belief that boys should be breast-fed longer than girls through these ideas. One old woman said, “The more willful the boy, the better.”

The different beliefs about the value of assertiveness for boys and girls correspond to their future positions in the hierarchy. Even though ḥasham really applies only to specific social situations involving persons of unequal status, women are so often in such positions that they must be trained to be modest in general demeanor—to be deferential, soft-spoken, obedient, and cooperative—or at least to be more sensitive to the social contexts in which modesty would be appropriate. Girls will grow up to be dependents, perhaps exchanging their positions as daughters for those as wives. At best, women, as matriarchs, can come to control some property and have influence over those men, usually sons, on whom they must depend to negotiate business and deal with the world of non-kin. Boys will nearly always grow up to become providers, if not for large groups of dependents, then at least for their own wives and children, and thus will not need to defer to many.

And yet there seems to be some ambivalence in Bedouin attitudes toward women’s willfulness. Whereas to say that a woman taḥashshams is always a compliment, to say that a woman is willful is not necessarily an insult. Women tend to view willful girls with some awe, and not a small amount of respect, even if as socializers they must scold them continually to keep them in line. Knowing the tremendous value placed on modesty, I was surprised when some older women, discussing the camp’s adolescent girls, agreed that the only ones worth anything were the three most assertive—they were the liveliest and brightest, although they certainly gave their mothers trouble. But one of these girls’ mothers said with some pride that she had been willful, just like her daughter, when she was young.

In fact, women are admired for many of the same qualities as men in Bedouin society. As Bedouins and people with aṣl, they are expected to express most of the same honor-linked virtues that legitimate the authority of their providers. The difference is that they can only express these virtues in contexts of social equality—that is, when they do not taḥashsham—when the ideals guiding their behavior are those of boldness and strength, not passivity. For example, a woman is expected to be energetic (ḥurra), industrious, enterprising, and tough (in both the physical and the emotional sense). Women do heavy work, putting up tents, gathering firewood, and getting water, and laziness is severely criticized. Intelligence, demonstrated in verbal skill in storytelling and singing, is also valued. Cleverness or enterprise, another sign of intelligence, is shown through success in business ventures, such as small-scale chicken and rabbit raising or sewing and weaving. The active capabilities of women are even celebrated in the ideals of feminine beauty. For Awlad ʿAli, who abhor slenderness, weakness, or sickliness in women as much as in men, the beautiful woman shines with the rosy glow of good health (ḥamra) and has a robust figure (mʿanigra).

Women who want to be respected must display, in addition to assertiveness, the moral virtues of generosity and honesty. The good woman (wliyya zēn) does right by her guests; she does her “duty” (ṣāḥbit wājib). The greatest offense is stinginess. Unwillingness to share personal belongings or the attempt to amass material goods at the expense of co-wives or other women in the household is frowned upon. In this context, women’s possessions do not include valuable property but rather small items such as bars of soap, perfume, cloves, and henna. No one is expected to share the personal wealth received at marriage or later, such as gold jewelry and clothing. Women in charge of household resources—primarily food—are expected to be generous with them and are criticized for failures to offer special foods to other members of the community. I heard bitter stories about how particular women had hidden pots of food from women passing by; the most vividly recalled incidents involved inhospitality to pregnant women. Some of these stories were fifteen years old and had not faded with the passing of time.

It should be clear from this digression into the expectations regarding women’s conformity to the cultural ideals that dependents, including women, strive for honor in the traditional sense. They share with their providers the same ideals for self-image and social reputation, which they try to follow in their everyday lives. Yet the situations in which they can realize these ideals, in particular those of independence and assertiveness, are circumscribed. Just as through defiance dependents can expose the authority of their providers as a sham, so can the more powerful expose their dependents for what they are—lacking in the key values of independence and ability to stand up in a confrontation.

It is perhaps this realization of vulnerability to humiliation that provokes feelings of ḥasham (shame, shyness, or embarrassment) in the presence of those higher in the hierarchy. It is rare to hear of someone who is shy or ashamed in general. Most often, the preposition from is used with the verb, to suggest that persons are “ashamed from” (or, in more idiomatic English, in front of) particular others. This interpretation is supported by the fact that two other words are used almost interchangeably with the phrase “he is ashamed/shy in front of”: “he is afraid of” (ykhāf min) and “he respects” (yiḥtaram).

Although we cannot know the subjective experience of shame, which seems to range from a basic lack of ease to extreme discomfort, we can deduce some of its qualities from several incidents. Once when I visited a strange household I felt dizzy and sick to my stomach, probably from the strain. When I described my symptoms to the people with whom I lived, they all nodded knowingly, saying I had been mitḥashma (adj.). Although I heard about other cases as severe, more common was a muted experience of shyness that individuals were anxious to escape as soon as possible.

Awlad ʿAli conceive of relative weakness or vulnerability in the idiom of exposure, the corollary being that protection involves nonexposure. The ideal form of nonexposure is avoidance, but when encounters must take place, the next best thing is cloaking or masking. Ḥasham, then, in its manifestation as emotional discomfort or shame, is that which motivates avoidance of the more powerful, and in its manifestation as the acts of modesty prompted by these feelings, it is the protective self-masking that occurs when exposure to the more powerful is unavoidable.

The categories of persons from whom a young man might taḥashsham are his father and male agnates of his father’s generation, together with men of the same generations from lineages of equal status to his own, and his older brothers, especially if they have succeeded the father in controlling the patrimony. Clients taḥashsham from their patrons and from anyone of the same status as their patrons. Women taḥashsham from some older women, especially their older affines, and from most older men, both kin and affines. They do not, however, taḥashsham from men who are clients, no matter how old, especially if they have known them for a long time. The general rule is that persons taḥashsham from those who deserve respect—those responsible for them and/or those who display the virtues of honor.

The idiom of exposure may have its roots in the way the life cycle is viewed. Because children are born helpless, the ultimate dependents, they are not only utterly vulnerable but also totally exposed to their powerful caretakers, who see them naked, defecating, eating, drinking. They have no self-control. As they grow and develop self-control and social sense, however, they become less dependent and have some choice in whether to obey their caretakers. They are also less exposed; they wear clothing, defecate in private, and are able to have secrets.

People feel embarrassed in front of their elders not just because the latter control resources and currently have authority, but also because the elders may have known them in an earlier state of extreme weakness and exposure. By the same token, individuals do not feel fear or shame in front of anyone they have seen exposed or vulnerable. Women never taḥashsham from younger men even if they depend on them and know that they control more resources, or from their husband’s or kinsmen’s clients—possibly because they have seen these men exposed or at least dominated by fathers, patrons, or whomever. Their common weakness vis-à-vis the more powerful unites these categories of dependents in relative equality, despite gender and social differences.

The cultural salience of the link between exposure and vulnerability or weakness is confirmed by the explanatory paradigms that Bedouins use to interpret illness and misfortune. The “evil eye,” magic, and possession—the three most common sources of illness and misfortune—all work through the victim’s exposure to more powerful forces. Holymen (fgīh) tend to diagnose illnesses as caused by being “looked at” (manẓūr). Magic works through the victim’s exposure to a charm or amulet, or merely to water in which a charm was soaked. Bedouins even believe that a new mother’s milk can dry up if she is exposed to the gold coins (frajallāt) on another woman’s necklace. Serious illnesses are usually caused by solitary encounters in deserted places with jinn (spirits), which, if they get too close, can “ride” the person and possess him or her. The experience of such encounters is always described in terms of fear. Fright also causes other illnesses, such as hepatitis, whose symptoms of yellowness are believed to be caused by the rise of bile accompanying a frightened gasp.

Safety in encounters with powerful forces, supernatural or social, is enhanced by avoiding encounters in the first place or by placing barriers between oneself and the force. The most popular protection against the evil eye, the jinn, and magic is an amulet, one or more pieces of paper on which a holyman has written Koranic verses or, more frequently, scribbles that people mistake for the verses. The word Awlad ʿAli use for amulet is ḥjāb, meaning a protection, cover, or veil; elsewhere in the Arab world the word refers specifically to women’s veils.

Likewise, to protect oneself from more powerful people one must taḥashsham, in the sense of acting modestly. That this involves cloaking or masking is apparent from the range of behaviors that Bedouins consider signs of modesty. First, there is dressing modestly, which for women includes veiling the face, a literal cloaking. Also masked are the “natural” needs and passions; so to taḥashsham from someone involves neither eating nor drinking in front of him or her, nor smoking (or, in Arabic, “drinking”) cigarettes. One also assumes a rigid posture and does not speak or look the superior in the eyes. These acts imply formality on the one hand and self-effacement on the other, both means of masking one’s nature, of not exposing oneself to the other.

Complete avoidance is the best protection; there is no danger of exposure if there is no interaction. Not just individuals but whole categories of unequals avoid each other. Sexual segregation and, to a lesser extent, generational segregation characterize the everyday social world of the Awlad ʿAli, and they are justified in terms of the ḥasham felt by those lower in the hierarchy. Thus, the Bedouins do not attribute the separation of the women and the young from the adult male world to the men’s wish to exclude the others; rather, they understand it as the response of the weak to their discomfort in the presence of the more powerful. The response of women when adult men intrude into their world certainly attests to the validity of this interpretation. Upon a respected adult man’s entrance, the only sounds are the rustlings of posture and clothing being adjusted and of wide-eyed children moving closer together, and then a hush falls on a roomful of garrulous women and boisterous children. The mood changes. Even well-born young men fall silent and seem uncomfortable in the presence of their older agnates; they do not laugh or joke but sit quietly, listening and ready to serve. Not surprisingly, they too prefer the world of their peers, of adult clients, or even of the women, their mothers, aunts, and grandmothers. By minimizing contact between those of unequal status, segregation limits the time the weak must spend feeling uncomfortable and acting with such restraint.12

Inequality is thus expressed as social distance, which is marked by ḥasham’s formality, effacement, and, ultimately, avoidance. Social intimacy, as between equals and among kin, is expressed in terms both of the absence of ḥasham and of the willingness to share everything, to expose oneself. These assumptions underlie the ritualized exchanges between hostess and formal guest. Whenever guests indicate they have finished eating, they are reprimanded by their hostesses: “What? Is that all you’re eating? What’s the matter with you? Are you mitḥashma?” The guest always responds, “Of course I’m not mitḥashma.” The rhetorical purpose of this exchange is to suggest that theirs should be a relationship of intimacy and equality, not inequality and social distance.

Ḥasham indexes hierarchical relationships. It is so accurate that when a young woman married into our community, some of the first questions she asked her husband’s young kinswomen concerned who taḥashshams from whom. This was her way of finding out about the status hierarchy in the community, information necessary for her own appropriate social responses. In their answers, the young women used smoking as a sign of ḥasham in relations between men, and veiling in relations between men and women.

What is all this protection for? What do the weak fear? These questions are difficult to answer, but I would suggest that at the bottom of ḥasham lies the fear that an encounter with someone more powerful will show one to be controlled—a state contrary to the ideals of autonomy and equality. Perhaps the fear or discomfort is due to the precariousness of self-image and of image in others’ eyes. Since women and, even more so, young men and clients share the cultural ideals of honor and measure themselves in its terms, masking and avoidance may be protection against being exposed as falling short of these ideals, which anyone who is not independent inevitably must.

Ḥasham is not thought of as a passive protection; it is conceived as arising spontaneously from the individual, and it cannot be coerced or imposed by the strong. People are held responsible for acting modestly. Whether ḥasham is a response to feelings of weakness and fears of exposure or just the modest acts that protect a person in such situations matters little: even if no feelings of vulnerability toward particular individuals are involved, by acting modestly a person shows at least some recognition of his or her relative position in the hierarchy, as well as respect, if not for the individuals with more authority, then for the system that gives those persons their authority. It is not compliance, but a form of self-control, and it preempts the need for a show of strength by the powerful—a show that would reveal the subordinate’s weakness. Initiated by the dependent, ḥasham is a voluntary act, a sign of independence, and as such, it is part of the honor code, applying to the dignified way of being weak and dependent in a society that values strength and autonomy. This strategy for the honor of the weak thus reinforces the hierarchy by fusing virtue with deference.