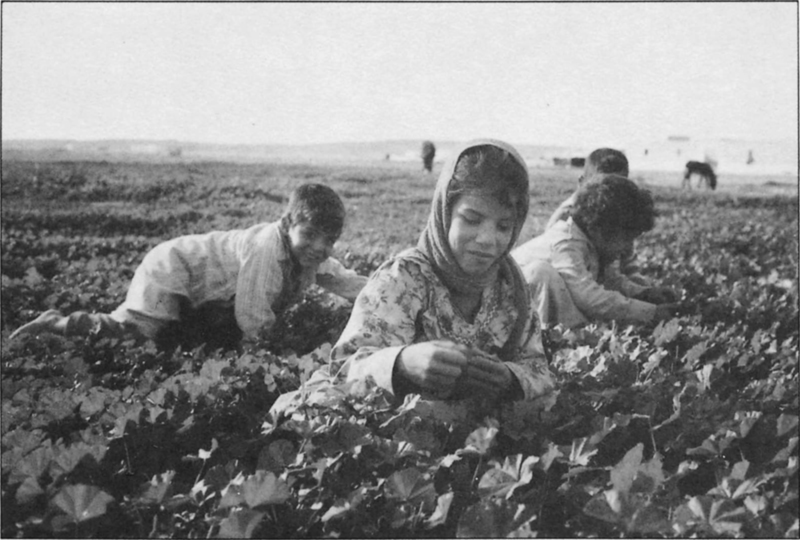

Children gathering khubbēza, a wild edible green

The moral discourse of honor and modesty is the means by which Awlad ʿAli rationalize the social hierarchy and inequities in the freedom of individuals to make choices about their lives and to influence others. Nowhere is this clearer than in Bedouin gender ideology. In Bedouin thought, the network of values associated with autonomy that I have called honor is generally associated with masculinity, as earlier descriptions of the “real man” suggested; modesty (ḥasham) is associated with femininity. Bedouins would not deny that some women can achieve more honor, in the strict sense of the term, than some men or that some men or categories of men (dependents such as young and lowly men) are more deferential than some women (older women and women from important families). Nevertheless, in the abstract, maleness is associated with autonomy and femaleness with dependency. This association corresponds to and reinforces the realities of both the Bedouin social system, with its basis in agnatic bonds, and the Bedouin economic system, in which senior men control resources and provide for others and women are the quintessential dependents.1 Because Awlad ʿAli couch hierarchy in the language of moral worth, the association implies that men’s precedence is due to their moral superiority.

The Bedouin valuation of masculinity over femininity is reflected in myriad sayings, institutions, rituals, and symbols, just as it is tempered by others. Although there are important sociological reasons for devaluing females, as Bedouins articulate in explaining their preference for sons over daughters, this devaluation is generally justified by reference to their moral inferiority. In Awlad ʿAli ideology, the primary source of this moral inferiority is the association of femininity with reproduction, which, although positive in itself, is tainted by its concomitants: menstruation and sexuality.

This identification of women with both menstruation and sexuality is thought to preclude them, in different ways, from achieving the moral virtue of those who uphold the honor code. It also determines the path they must take to gain respectability, the path of modesty. In this chapter I will show why chastity or sexual modesty, as an aspect of the social deference of ḥasham, is essential to a woman’s honor. I argue that the denial of sexuality that is the mark of ḥasham is a symbolic means of communicating deference to those in the hierarchy who more closely represent the cultural ideals and the social system itself. This denial is necessary because the greatest threat to the social system and to the authority of those preferred by this system is sexuality itself.

One of the ways Bedouins express the value of males over females is their avowed preference for sons. Both men and women say things like, “Men gather women together [marry wives] to have sons. Daughters are worthless.” Pregnancies are thought to differ depending on whether a boy or a girl is being carried. If a woman is fat and swollen, feels heavy, and sleeps a lot, people predict she will give birth to a girl; a woman carrying a boy is said to be light, remaining so throughout the term of pregnancy, and she sleeps little, especially in the last month.

People greet the birth of a boy with more enthusiasm than that of a girl. In describing her activities as a midwife, one old woman proudly told of the happy time she delivered two boys in one day. She explained:

To give birth to boys is better. Everyone present rejoices. They run to tell the father that he has a son. If it is a girl, everyone is upset: those who delivered her, those in attendance. They don’t go to tell the men. No one eats dinner. Even the tent goes into mourning. When it is a boy, the tent is happy, the father is happy, the uncles are happy, and the mother—I can’t tell you how happy she is!

When women visit a new mother, they enter ululating and eagerly offer their congratulations if she has delivered a son. If she has given birth to a girl, they offer the phrase “Thank God for your safety [al-ḥamdullāh ʿale slāmtik].” People generally greet the birth of a girl with the philosophical statement, “Whatever God brings is good.” One father, hearing that his wife had delivered a daughter (her fifth daughter, out of seven children), commented, “It’s all the same.” But his fifteen-year-old daughter was less neutral; she responded to the news with the disparaging rhyme “A little girl, may she have cramps [bnayya, aʿṭīhā layya],” for which the older women immediately rebuked her, saying, “Shame on you, girls are nice!” People acknowledge that the death of a male infant is more disturbing than the death of a female, although both elicit reactions of sadness mingled with resignation to the will of God.

Yet the stated preference for boys is not reflected in the way boys and girls are treated in their early years or in the affection their mothers, fathers, and others show them as infants and toddlers. Although people believe that boys should be breast-fed longer than girls, as we saw in the last chapter this is a function not of preference for boys but of ideas about the relationship between indulgence in childhood and the development of fearlessness. In fact, weaning depends largely on idiosyncratic factors and circumstance, and its timing varies considerably from family to family, and even within a family, regardless of gender.

There is good sociological reason to prefer sons. The tribal system is organized around the principles of patrilineality and agnatic solidarity and is based on relationships between men. However important affines and cognatic kin are economically, socially, and affectively, tribal segments can only grow through the addition of males. Strength is measured in numbers of men. It is therefore not surprising that men unequivocally prefer sons.

Because the tribal system is so male-oriented, the interests of men and women do not always coincide. Women’s attitudes toward sons and daughters are more complex and ambivalent than men’s, a fact the Bedouins recognize. They say, “A girl is in her mother’s interest, and a boy in his father’s [il-binit fī maṣlaḥit umhā wil-wad fī maṣlaḥit būh].” The preference for sons in any particular family is tempered by a desire for daughters who will help with the household work. Even if a household of girls is pitiful, people recognize the practical difficulties of managing a household of men and boys. The ideal, then, is to have many sons and a few daughters. Mothers and daughters are close and interdependent, spending a great deal of time together. Mothers rely on their daughters for help with work, for companionship, and, later in life, for care, and most relationships between mother and daughter are emotionally close.

Yet, on the whole, women share their husbands’ preference for sons because of the way social and economic life is organized. Sons are a woman’s social security. She is initially happy to give birth to sons because this secures her position in her marital community and with her husband. Later, once the sons inherit from their fathers, she depends on them for support (Bedouin women, like women in our own society, tend to outlive their husbands). In the case of divorce, a woman often lives in the household of an adult son (if she has one), gaining a position of some independence and power, his wife or wives performing services for her, and his children living near her.

The heart of the problem with girls, as far as their mothers are concerned, is that because residence is virilocal and descent patrilineal, unless they marry patrilateral parallel cousins, daughters leave their natal groups and their mothers, and their children belong to another tribe. One woman explained, “A daughter will leave, she’ll marry and abandon you. She won’t even get news of you. But if you are fortunate, a son will support you and look after you when you are old. Girls may be more tender [ḥanūn], but they leave. That is, unless they marry within the camp.”

A daughter who marries outside the camp can only come to visit when her husband or his kin allow it, and she can rarely be spared from her own household for any length of time. The social distance between her children and her natal group varies, depending on numerous factors, but, despite fondness for maternal relatives, the jural and political distance cannot be surmounted. An old woman’s statement about a daughter who had married into another group living nearby confirms the importance of this factor. She explained that she preferred her daughter to all of her sons (prosperous, respected men in whose camp she lived as a matriarch) because the daughter came to visit and cared for her when she was ill, whereas her sons didn’t even ask after her (an exaggeration). Nevertheless, she preferred her sons’ children to her daughter’s because the latter “belong to someone else.”

Although the tribal system organized around patrilineal descent and inheritance and virilocal residence by definition slights females, preventing them from attaining the social statuses open to men and peripheralizing them in the patriline, it does give them a place, however temporary, with their brothers in the tribe and lineage. No one denies that women can have the nobility (aṣl) of genealogy or even that they can pass a bit of it on to their children (Abou-Zeid 1966, 257). In Bedouin thought, women’s secondary status is based on a kind of moral inferiority defined by the standards of the honor code by which individuals are measured.

Male and female are symbolically opposed in Bedouin thought. Above all, females are defined by their association with reproduction, not so much in its social aspect of motherhood, but in its natural aspects of menstruation, procreation, and sexuality. These natural qualities are symbolically highlighted in the colors of female dress, especially in the ubiquitous red belt, whereas male dress communicates men’s more cultural (and religious) qualities. Women’s association with nature is seen as a handicap to their ability to attain the same level of moral worth as men. Women’s lack of independence from nature compromises them vis-à-vis one of the crucial virtues of honor, the self-mastery associated with ʿagl (social sense or reason).

Beliefs about women’s moral inferiority in terms of other honor-linked values besides self-mastery also abound. Most of the statements I heard about these beliefs were asserted by men; women rarely volunteered them, although they also rarely contested them. For example, men are said to be stronger and more fearless than women. Women are said to fear the dark and not to be able to “take much” (mā yitḥammalūsh). Men’s talk is said to be full, whereas women’s is empty or ignorant. Some say that whenever two women talk, the Devil is there between them. Most important, men are said to be more honest and straightforward. One man illustrated this point with this version of the Fall from Grace:

God created Eve from Adam’s bent lower rib. That is why women are always twisted. They never talk straight.In the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve had everything. One day the Devil was playing a flute [zummāra], and Adam and Eve listened. He stopped playing and said to Eve, “Eat these tasty fruit (off the tree that God had forbidden to them), or I won’t play for you anymore.” Wanting to hear the music, she agreed. They had thought the reason they were forbidden to eat the fruit was that it was poisonous, but when Adam saw that Eve did not fall ill or die when she ate it, he went ahead and ate too. As he was swallowing, he thought better of it and the fruit stuck in his throat. This is why men have Adam’s apples.When God saw that Adam and Eve had disobeyed him, He banished them to earth. Eve landed in the west, and Adam in the east. They began looking for each other, she traveling eastward, and he westward. The halfway point was Mt. ʿArafat (near Mecca). Eve arrived there first. When she saw Adam coming, she immediately sat down and acted as if she had been there all along. When he approached her, they greeted each other and embraced. Eve turned away and tried to pull out of the embrace. She did not let on that she had been as anxious to find him as he had been to find her. To this day women are like that. They always try to pull away and pretend they don’t care.2

These signs of moral inferiority are not exclusively female, however. Everyone recognizes that men can also be dishonest, ignorant, cowardly, and so forth. If that were not the case, these values would hardly provide the standards by which moral worth could be assessed and hierarchy justified.

It is the association with nature that is special to females, the source of both their positive and negative value. Bedouins do not devalue all that is natural and related to reproduction. For instance, as reproducers, women are responsible for giving birth to the children that are so desired and adored. Everyone wants children, and men want as many as they can have and support. Women, overworked, fatigued, and not in the best health, want fewer merely because they cannot cope with the work involved in bringing them into the world and caring for them. Yet if they have trouble conceiving or carrying pregnancies to term, they turn to ritual specialists, folk healers, or doctors for help. Fertile women are valued, admired, and envied. Barren women face a sad life, certain that their husbands will, at the least, take second wives.

The association of females with fertility extends from their role as reproducers to ideas about general plenty. A saying that often came up in response to news of the birth of a girl was “A year of girls is a year of bounty” (sanat banāt sanat khēr)—that is, baby girls bring good pasture, so milk and butter are plentiful; in a year of boys there is no rain, no pasture, and no milk.

Girls are linked symbolically to rain (necessary for both the pasture and the barley crop on which livelihood depends) in a more explicit way through rituals that were performed formerly in times of drought. Awlad ʿAli have a calendar of seasons based on the movement of constellations through the winter sky, which they rely on to time barley planting and to predict the lushness of spring pastures in the desert, both of which depend on the amount and timing of rainfall. Rain is essential in the period known as jōza, which occurs around mid-December. In the past, when there was no rain during this month the children performed a ritual to bring rain. Central to the ritual was a doll called the zirrāfa, fashioned by lashing together a bread shovel (used in bread baking) and a weaving shuttle, both items associated with female activities. The doll was clothed in a red dress, a red belt, and a silk kerchief, “like a virgin.”3

Women’s relationship to certain life-cycle rituals also reflects their symbolic association with fertility. Women are more closely linked to life, and men to death. Not only do men slaughter animals, but they also exchange sacrificial sheep at ceremonies, including funerals. Women do not slaughter, and although they attend all ceremonies, they do not bring gifts or make exchanges at funerals. Following childbirth, however, women pay visits to new mothers and bring them gifts, whereas men do not visit or, as a rule, give gifts to new mothers. At all other ceremonies, both men and women attend and have parallel, if separate, gift exchanges.

The possession of a womb for fertility carries with it other positive moral qualities. In the following folktale, told to me by an old woman during a discussion of the relative value of boys and girls, the difference in moral nature between a compassionate and loving daughter and an abusive and heartless son is rooted in their physiological differences.

There once was a woman with nine daughters. When she became pregnant again she prayed for a boy and made an oath to give up one of her daughters as an offering if she were granted a son. She did give birth to a boy. When they moved camp, riding off on their camels, she left behind one daughter.Soon a man came by on a horse and found the girl tied up. He asked her story, untied her, took her with him, and cared for her.Meanwhile, the boy grew up and took a wife. His wife demanded that he make his mother a servant. He did this, and the old mother was forced to do all the household work for her daughter-in-law [a reversal of proper relations between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law].One day they decided to move camp. They loaded up the camels and traveled and traveled. The old mother had to walk, driving the sheep. She got tired and was eventually left behind. Lost, she wandered and wandered until she came upon a camp. The people in the camp called to her and invited her in. They asked her story. She told them she had not always been a servant and recounted her tale. When the people in the camp heard this story they went running to tell one of the women. It turned out that she was the old woman’s daughter who had been abandoned as a child. She came, questioned the old woman, and, once convinced that it was really her mother, embraced and kissed her, took her to her tent, washed her clothes for her, fed her, and cared well for her.By and by, the son came looking for his mother. He rode up to the camp and asked people, “Haven’t you seen an old servant wandering around?” The woman who (unknown to him) was his sister invited him into her tent. She demanded that a ram be brought and slaughtered in his honor. She then asked him, “Where is the riḥm [womb] of the ram?” The brother looked at her in surprise answering, “A ram has no riḥm, didn’t you know?”She then revealed her identity and told him her story. She refused to let him take his mother back and scolded him for having so mistreated her.

The moral of the story turns on the double meaning of the triliteral root raḥama, from which the word riḥm (womb), as well as a word meaning pity, compassion, or mercy, is derived. Thus the story links wombs (femaleness) with compassion and caring. The old woman who told me the story added this commentary:

You see, the male has no womb. He has nothing but a little penis, just like this finger of mine [laughingly wiggling her finger in a contemptuous gesture]. The male has no compassion. But the female is tender and compassionate [idh-dhakar mā yirḥamsh, l-anthā tḥinn wtirḥam]. It is the daughter who will care for her mother, not the son.

From this story and the old woman’s comment, it is clear that despite the avowed preference for boys in Bedouin culture and society, certain positive values are associated with females, particularly in their relationships to other women, especially their mothers. The contrast between the son’s abuse of his mother and the daughter’s care and forgiveness is striking, and it is tied to a difference in their nature, for females possess wombs.

The positive value accorded females through their association with fertility is countered by the negative value of fertility’s partners, menstruation and sexuality. Each of these two factors impedes women’s abilities to realize the ideals of honor in a different way. Menstruation compromises women’s virtue by undermining their piety. As a natural force over which they have no control, it also represents inescapable weakness, and lack of self-control or independence. Sexuality, as I will show, threatens the whole male-oriented social order. Insofar as women are more closely associated with sexuality through their reproductive capacities, they represent not the embodiment of that social order, as do the mature men at the top of the hierarchy, but its antithesis. And because honor is attained through embodying the cultural ideals, in this sphere, too, women are morally inferior.

Piety is an aspect of morality that women cannot easily attain because of their “natural” pollution through menstruation. One version of the Fall from Grace relates how Eve had not menstruated in the Garden of Eden but only began to bleed when she hit the ground in her fall. Women’s monthly menstruation commemorates the fall into earthly sin, or at least to that which is not godly. Although there are five pillars of Islamic faith and practice (declaration of faith in the unity of God and Muhammad’s prophecy, prayer, alms, the pilgrimage to Mecca, and the Ramadan fast), prayer is the duty that defines piety most vividly on a daily basis. Women are handicapped because menstruation is considered polluting. A menstruating woman cannot pray.4 In fact, the polite Bedouin term for menstruation is “that which forbids prayer” (ḥirmān iṣ-ṣalā). Islamic convention stipulates that a menstruating woman may not enter a mosque or touch holy objects, the Koran in particular. Furthermore, her fasts do not count, which means that she must make up at some other time during the year the days of the Ramadan fast that she misses. Bedouin women exaggerate the uncleanliness of menstruation by abstaining from bathing or even hair combing while menstruating. The bath that marks the end of the flow is also a ritual ablution; after this bath, a woman may resume prayers, not to mention sexual intercourse. In contrast, men face no “natural” restrictions on the performance of their religious duties. Most Bedouin men (at least in the community in which I lived) try to pray five times a day, both showing their piety and assuring their continual purity in the ritual ablutions that precede each prayer.

The uncleanliness associated with menstruation is not restricted to the days when a woman is actually menstruating; rather, it taints all females from the onset of menarche until menopause, and even after. Men are symbolically associated with purity, the right (the sacred), and the color white.5 Men tend to sit on the right side of the tent, and women on the left. When asked why, people simply explain that men are “preferred” (afdׅhal), a term with religious connotations. White is, along with green, one of the colors of Islam, and pilgrims to Mecca wear unseamed white cloth. The quintessential item of Awlad ʿAli men’s clothing is the jard, a white woolen blanket worn over the robes and knotted at one shoulder like a toga. Women are associated with uncleanliness, the left, and the colors red and black (whose symbolic significance will be discussed in the next section). They never wear white. Even when women go on the pilgrimage to Mecca, they prefer not to don white pilgrim’s garb, but would rather retain their traditional black headcloth, if not also a black full-length dress, and their red belts, the essential pair in women’s dress.

The religious basis of the purity/impurity distinction and the intensity of feelings on this subject were vividly exposed when I unthinkingly threw an item of women’s clothing into a washtub of men’s clothes. The women gasped and rushed to remove the item, scolding me for mixing men’s and women’s clothing. They told me that women were unclean and that their clothes and children’s clothes were washed separately from those of men and of postmenopausal women, whose clothing (other than underwear) could be washed with men’s. By way of explanation, they merely said, “Men pray.” The implication was that men were pure and religious, as are postmenopausal women, who, for the most part, also pray regularly. Young women in their reproductive years tend not to pray so regularly, often excusing themselves on grounds that, thanks to their many children, they are too messy and too harried to take the time to perform the proper ablutions in preparation for prayer. Yet even if they wished, they could not pray regularly because of menstruation.

The religious and ritual distinction between males and females is also evident in the ban on women slaughtering animals. All animals must be ritually killed according to Islamic rules: the person must face Mecca and slit the throat quickly in one stroke while pronouncing allāhu akbar (God is great). According to Bedouin custom, only men may slaughter, a restriction that often creates inconveniences for people. A common sight in the camp was that of girls running frantically from household to household carrying rabbits by the ears or chickens by the feet in search of a man to slaughter the animals their mothers wished to cook. The ritual impurity of females is apparent in solving the problem of who may slaughter in the complete absence of men. I was told that when no man can be found, a postmenopausal woman is permitted to sacrifice the animal, but only if she places the knife in the hand of a circumcised boy. She grasps his hand in hers as she actually slits the neck, but it is the boy who must utter the religious formula. The unequivocal purity of maleness per se is clear: even a nonpraying boy is considered more pure than a praying, nonmenstruating woman.

A more serious source of female moral inferiority is sexuality, with which women are intimately associated through their reproductive functions. Pregnancy is itself incontrovertible evidence of sexual activity with no equivalent among men, and fertility activated by sexuality is what defines younger women as females. Indeed, since fertility calls attention to their sexuality, women downplay it;6 they even try to keep pregnancies secret for as long as possible, disguising the size of their bellies with their wide belts. Childbirth, although positive in that it produces the children so prized in Bedouin society, is considered polluting. Some men will not even eat food cooked by a new mother. The ambivalence about reproduction is reflected in the mixed attitudes toward women who have just given birth. A new mother, described as closer to God because her prayers are more readily answered, is also identified with the unclean menstruating woman: she is sexually taboo (for forty days after giving birth), is discouraged from bathing, and may not perform her prayers until she ceases bleeding.

Why would the association with reproduction, and especially the sexuality necessary to it, contribute to the moral inferiority of women? The answer has two parts, corresponding to two values in the Bedouin honor complex that sets the standards for moral worth. The first value concerns the individual’s relationship to his or her natural passions and functions; specifically, it is the value of independence and self-mastery. Sexuality and reproduction, like menstruation, are negatively valued as “natural” events over which females have little control, thereby providing the avenue through which others come to control them. As such they diminish women’s capacities to attain the cultural ideal of self-mastery. Men want children to perpetuate lineages, and women are the vehicles; their value as reproducers leads men to want to control them. Through sexuality and pregnancy, women lose control over their own bodies. Paradoxically, the children, who later secure a woman’s position, initially make her more dependent on her husband, thus increasing his control: she is tied to him by her children, whom she would lose if she left through divorce or her own choice. Even in her daily life she has less freedom to travel and visit or merely to control her own schedule.

The association of lack of independence with women’s sexuality and reproduction is obvious from the instances in which Bedouins characterize particular women as either masculine (mtdhakkara) or like men (kēf ir-rājil). The former are older, postmenopausal women who, having ceased menstruating, are no longer reproductive and are less sexually active (usually being divorced, “left,” or widowed), more pious, and less controlled by others. The women described as being like men are women without men. One divorcée who refused to consider remarriage was teased about being like a man. Another woman whose husband had “left” her (had ceased sleeping with her but had not officially divorced her) told me she was “living like a man.” A slightly older woman who had divorced quite young and never remarried was often referred to as masculine. These women had two basic things in common: they were not under marital control, and they were not reproducing. Because the Bedouins for the most part do not have any systematic or reliable form of birth control, only for men and postmenopausal women can sexuality be divorced from reproduction, hence concealed.

The second value of the honor complex that women’s association with sexuality prevents them from embodying is conformity to the ideals of the social order inherent in the concept of ʿagl (social sense). We have seen that mature men are expected to conform to and uphold—in fact embody—the social order and its ideals to justify their positions at the top of the hierarchy. But sexuality, as I will show, is a threat to the social order. It follows, then, that greater ʿagl implies distance from sexuality and that females, being closely tied to sexuality, have less of the honor that accrues from greater ʿagl.

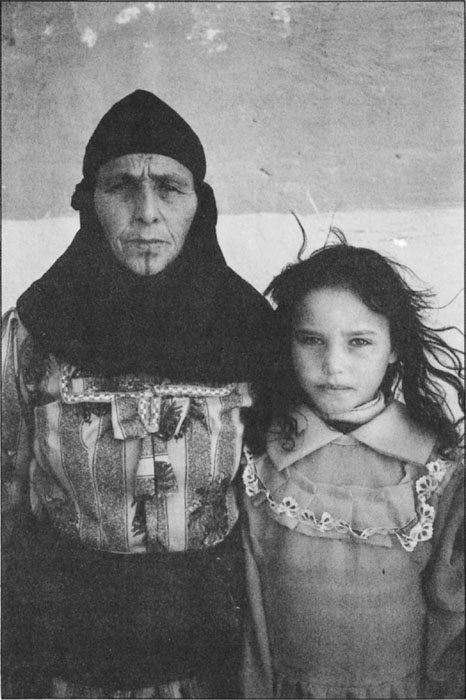

Gender symbolism, in particular the symbolism of the two distinctive items of women’s clothing, the red belt and the black veil, illuminates Awlad ʿAli ideas about the female association with sexuality. For women, sexual knowledge and activity go with marriage, and the transition from virgin to woman is radical. The positive value of fertility, discussed above in the context of rain rituals and the symbolic associations with plenty, is tied explicitly to virgins and not to adult, married women, for whom its unambiguous character is lost. The transition is dramatically marked by a change in a girl’s clothing.7 In traditional weddings, the bride is completely covered by a man’s white toga (jard) from the minute she is brought from her father’s house until the defloration, which usually takes place in the early afternoon of the wedding day. From then on she begins to wear married women’s clothing, which consists of two critical pieces: the black headcloth that doubles as a veil and the red woolen belt. These represent Bedouin womanhood. People often said to me, “Wear a veil and a belt and you’ll be a real Bedouin woman [tgannaʿī wtḥazzamī wtigbī bduwiyya].”

The red belt that every married woman wears symbolizes her fertility and association with the creation of life. Red, as we saw in the symbolism of the rain ritual, is associated with femaleness and fertility. It is the color of weddings and circumcisions, both ceremonies that celebrate sexuality and fertility. On both occasions a large red blanket is draped on the tent or even on the automobile carrying the bride to her groom’s home. Belts are also linked to fertility; the onset of menarche is followed by the gradual transition to wearing some kind of belt, usually only a colorful kerchief until marriage, when the red belt is required. To go without a belt is considered highly indecent or shameful. When I first arrived in the field, I wore blouses and full-length skirts. The adolescent girls criticized me for not wearing a belt, although the skirts had waistbands. I began to wear a kerchief around my waist and everyone was pleased.

When questioned about the meaning of women’s belts, one man explained that young girls did not need to wear them because “they don’t know anything,” the implication being about sexuality. Then, somewhat embarrassed, he explained that for an adult woman to go without a belt signaled that she was “ready for anything,” again implying sexuality. In fact, the only time women remove their belts is when they sleep with their husbands, so the association is not spurious. Most women defended the belts as customary and condemned women who did not wear them (the Egyptians, for example) as shameless, but they also explained that they needed to wear them because they had to work hard and might strain their backs if they did not wear belts. Even this argument provides indirect support for the association of belts with fertility and reproductive capacity, since menstruation is also sometimes called “the back” and is thought to originate in that part of the body, just as children are said to come from “the back.”

Consideration of colors other than red for belts confirms this interpretation. One day I tied a black kerchief around my waist and was immediately reprimanded. When I asked why, one woman responded that it was forbidden (ḥarām) to wear dark colors around one’s waist because it showed a refusal to be grateful for “the life God brings.” A woman in mourning for a close relative substitutes a white cloth for the red belt. Although I was unable to get an explanation for the white belt’s meaning, it may represent the loss of interest in life, since the end of mourning and a woman’s return to ordinary life and concern with the living are marked by resuming the red belt; those in mourning also stop using henna (which dyes hair red) and refrain from dyeing wool for weaving (red being the dominant dye color). Whether white in this context has associations with purity, religion, and masculinity I do not know.

The red belt cannot be worn if the black veil is not also worn. In the towns, where Bedouins have been influenced by Egyptian fashions, many women dispense with the red belt, but they usually retain the black headcover. Everywhere in the Muslim world the head is covered as a sign of modesty. Bedouin men also cover their heads, and they consider those who do not brazen and lacking in religion. Bedouin women’s headcovers double as veils. They do not wear stiff masks, as in the Persian Gulf area, or permanent veils covering nose and mouth, as in Morocco. Rather, their not-quite-opaque black headcloth is draped and knotted in such a way that it can be lifted to cover the whole face, dropped to reveal it, or draped in intermediate ways depending on the status of the person with whom the woman is interacting. The complex rules and social meaning of veiling will be explored in the final section of this chapter.

Black is a color with numerous connotations, most of which are negative. Black is often opposed to white, the color of religion and purity. In Bedouin expressions describing human character, for instance, well-meaning, sincere, and nonmalicious people are “white-hearted,” and those who act in bad faith or with malicious intent are “black-hearted.” Social respectability translates into a white face, as when people assert that they have nothing to be ashamed of or to hide. However, someone who has been shamed or whose reputation has been besmirched is said to have had his or her face blackened. Veils literally blacken the face; thus, they symbolize shame, particularly sexual shame.

The veil is not the only article of women’s clothing that is black. In the past, women wore black overdresses when they traveled long distances or paid formal social calls. Older women still wear these dresses, but many younger women have abandoned the practice. Nevertheless, all women still wear a black shawl, called a milāya (an item of Egyptian peasant and baladi dress), whenever they make formal visits. One clue to the meaning of the black overdress and shawl, and ultimately the black veil, can be found in the comment of a woman as she watched her young, lower-status neighbor set off to a wedding in the village nearby. The young neighbor was wearing a black overdress made of translucent rather than opaque cloth. The older woman noted that many considered these new overdresses unrespectable and provocative, and their wearers shameless.

This association of black with shame is confirmed in a rich folktale of mother-son incest a woman related one evening to an audience of women and children. The moral of the story places the origins of women’s black veils in their antistructural sexuality. But the tale also carries messages about the complex relationship between women, sexuality, and morality. In the version below, the asides and comments of the woman telling the story are in parentheses.

Once there was a barren woman who asked a traveling holyman [fgīh] for some medicine to make her fertile. He gave her something that looked like eggs and instructed her to cook them but not to eat them until the next morning. She cooked them, then left to fetch water. While she was gone, her husband returned, peeked in the pot, found the “eggs,” and ate them.When she came home and saw the empty pot, she was alarmed. “Oh no!” she said, “now you’ll get pregnant.” Her husband didn’t believe her but later realized that he was pregnant. Time passed. Then one day he felt labor pains. He came to his wife and asked her what to do. She replied, “Go out and squat behind that bush and deliver the baby. If it’s a boy, bring it home. If it’s a girl, just leave her there.” He went and pushed and pushed, hanging onto the bush until he gave birth. He took off as fast as he could.A bird came along and carried away the baby girl. He put her in a nest high up in a tree and brought her food every day. She grew up to be the most beautiful girl imaginable. No one surpassed her in beauty.Now, under this tree was a spring. Muḥammad būh Sulṭān, living in a castle not far from there, had a beautiful horse which he sent out with a slave to be watered there. But when they approached the spring, the horse reared and refused to drink. Muḥammad būh Sulṭān was furious when they returned, shouting, “What do you mean she wouldn’t drink?” So he beheaded the slave. The next day, he sent out another slave to water the horse. The same thing happened. So the third day, he decided to go himself. When they approached the spring, again the horse reared, but as it did, he caught a glimpse of the girl’s reflection in the pool and immediately fell in love with her.He went to an old woman and told her he wanted the girl. She said she could help him, but he must bring her a small tent, a ram, a cooking pot, and a grindstone. He did. She went with this stuff and started pitching the tent under the tree in which the girl lived. She set about doing everything wrong, trying to pitch the tent upside down and putting the poles on the outside. The girl called down, “Grandmother, not like that. You’ve got it upside down!” The old lady responded, “Oh please, come down and help me. Show me how.” But the girl refused. Finally the old woman managed to pitch the tent.Then she started sacrificing the ram, taking the knife to its leg. The girl called down, “No, Grandmother, that’s not how you sacrifice a ram. You slit its neck.” The old woman said, “Oh please, child, come down and show me how to do it.” The girl refused.Next the old woman built a fire and put the pot on it, bottom side up. The girl called down, “Oh, Grandmother, that’s not how you cook. Put the pot right side up.” The old lady said, “Please come down and show me how.” The girl again refused. Then the old lady took the ram without killing it and tried to cram it whole into the pot. Again the girl called down, “Grandmother, that’s not how you cook meat.” The old lady again begged her to come down, but she refused.After getting the ram into the pot, she set about grinding some wheat. Instead of putting the wheat on a cloth, she put it directly on the ground and started grinding. The girl called down, “No, no, Grandmother, it is forbidden [ḥarām] to put God’s blessing [niʿmat rabnā] on the ground. Lay down a burlap sack or something first.” The old lady ignored her. The girl climbed down, took the wheat, and placed it on a sack.Now Muḥammad būh Sulṭān had hidden himself nearby, and when the girl stooped over he jumped out and grabbed her, put her on his horse, and took off. She cried and screamed all the way, “Damn you, Grandmother! Damn you, Grandmother!” She did not stop screaming until they got to the castle. Then he talked to the girl. He said, “Please live with me. If you want me as a father, I’ll be that. If you want me as a brother, I’ll be that. If you want me as a husband, I’ll be that.” She married him. (She knew what was in her best interest!)The only other person in the castle was his mother, an old woman. Now, Muḥammad būh Sulṭān decided to make the holy pilgrimage to Mecca. Before he left, he gave his mother and wife a ram, saying, “If one of you dies, the other will slaughter this ram over her. If my mother dies, bury her in the courtyard.” Then he went to his wife and told her, “For my sake, do anything my mother asks of you, even if she asks you to take out your own eyes.” (She had gorgeous eyes.) Then he set off.Immediately, the mother-in-law started picking on the girl. She asked her to take out her eyes and the girl agreed. The old lady, with these beautiful new eyes, threw the girl out of the castle. Now blind, the girl left. She walked and walked until she encountered a “magaṣṣ”8 being chased by a large snake. He begged her to hide him from the snake, promising that she could have anything she wished if she would help him. So she hid him in an empty grain bin. When the snake was gone, he came out and thanked her. Then he asked what she wished for. She asked for a castle twice as big as her old one, a new pair of eyes, and an orchard full of every conceivable fruit tree. He granted her these wishes, and they lived together in the castle.When Muḥammad būh Sulṭān returned from the pilgrimage, the woman he found started weeping. “We slaughtered the ram over your poor old mother,” she said. Indeed, he found a grave in the courtyard. But he found his wife quite changed. “Why is your skin so tough? Why has your body aged so?” he asked. She replied, “You’ve been gone a long time.” So they lived for a while as man and wife. (Muḥammad and his mother.)Then one day, the woman announced that she was pregnant. (A lie, she was too old to conceive.) She said she had a pregnancy craving [tawaḥḥamat] for some grapes. So Muḥammad sent a slave to the castle that had sprung up in his absence to ask for some grapes. The slave went off to the castle and said to the mistress who greeted him, “The wife of Muḥammad būh Sulṭān has a craving for some grapes, won’t you give us some?” The woman answered, “What a lie! That’s not his wife; that’s his mother!” She told the magaṣṣ to cut out the slave’s tongue so he wouldn’t talk. The slave came back empty-handed with his tongue cut out. Muḥammad was furious. The next day he sent another slave, who also returned with his tongue cut.Finally, he decided to go himself. When he got there he said, “Don’t you have any grapes for the wife of Muḥammad būh Sulṭān? She has a pregnancy craving.” He heard the woman respond, “What a lie, that’s not his wife; that’s his mother.” He was shocked and asked, “What do you mean?” Just as the magaṣṣ was about to cut out his tongue the woman recognized her husband and stopped him. She related what had happened in his absence: how his mother had taken her eyes, thrown her out, and buried the ram whole in the courtyard.Muḥammad returned to his castle and demanded that his “wife” dig up his mother’s grave. She tried to dissuade him, pleading, “No, no. Why do you want to see her?” He insisted, and when they dug it up he found the ram. Furious, he threw his mother into the fire. [The listeners, mostly young girls, were shocked. The woman telling the story commented, “That’s what she deserved!”] Then he brought his true wife back to live with him.

Although this tale is so rich and complex that it could be analyzed on many levels, I will note only a few points. By linking women’s black veils to the shameful act of incest, it supports the association of females with a negatively valued sexuality. It is telling that women are associated not just with the ordinary sexuality of marriage, but also with an illegitimate sexuality that violates social and religious norms. Mother-son incest threatens the primacy of bonds between men and the control of fathers over the marriages of sons—the foundations of the Bedouin social order. In this tale, there is no father, only a mother. Furthermore, the old woman’s sexual desire is not redeemed by a potential contribution to procreation, as she is postmenopausal and infertile. Thus, the black veil of shame is closely tied to a sexuality stripped of its positive association with fertility and out of the control of senior men. I will return to this point in the next section.

By presenting two types of women, the tale carries even more important messages about female moral worth. From the discussion of gender thus far, it might seem that Bedouins perceive women’s moral inferiority to men as absolute, associating women, on the one hand, with “nature,” symbolized in the balanced pairing of the red belt of fertility with the black veil of sexuality, and men, on the other hand, with white, the color of religion, that which is most “cultural.”9 But the tale clearly distinguishes between good and bad females, opposing the evil old mother driven by sexuality and the beautiful, virtuous woman.

Through its depiction of a good woman, this tale indicates that female moral worth is variable and hints at the ways women can counteract their moral inferiority. First of all, the good woman is the most male woman, symbolized by the father giving birth to her. In social life, the equivalent might be a woman who maintains close ties to male kin. Second, she is pious, which identifies her with a critical source of moral virtue. The young woman’s good character is demonstrated by her inability to let the old woman commit the sacrilege of letting wheat touch the ground. Third, she is respectful, obeying both her husband and his mother to the point of giving up her eyes. Finally, she is chaste, claiming not to want a man and protesting violently when forcefully abducted. In short, through proper action, in particular through ḥasham, a woman can at least partially overcome the inferiority that is hers through her “natural” functions. To understand why this is so, the place of sexuality in the Bedouin system must be explored.

The roots of sexuality’s negative value in Bedouin thought lie primarily in the social order. Where common descent and consanguinity provide the primary, and only legitimate, basis for binding people together, the sexual bond is a threat in that it unites individuals outside of this conceptual framework of social relations. This interpretation conflicts with Mernissi’s (1975); she locates Moroccan society’s negative valuation of sexuality in the religious order, arguing that Islamic doctrine and belief associate women with chaos (fitna) and enjoin men to avoid women lest they succumb to female seductions instead of directing their energy toward God and the social order. I argue, rather, that this negative attitude toward sexuality is identified with religion only because piety constitutes one of the standards of moral worth in a Muslim society. Insofar as Islamic belief and practice represent the highest ideals of Bedouin society, identification of the prevailing social system and status quo with Islam is inevitable—it accords the society legitimacy. But religious ideals are then confused with social ideals, and personal honor comes to depend on conformity to both.

There is a religious basis for the belief that sexual intercourse is polluting. For example, it is forbidden to pray or to enter a mosque in the unclean state following intercourse. Yet to counter this pollution men and women need do no more than observe certain restrictions and perform simple purificatory acts. Awlad ʿAli explain that intercourse must be followed immediately by bathing to minimize the chance of encountering anyone while still “unclean”; they add that care must be taken to avoid spilling the bath water anywhere people are likely to walk. The soap used in these baths should be kept away from children or those who pray. To appear before children in the clothes worn during intercourse is believed to cause them eye problems.10 Furthermore, Bedouins said it was forbidden (ḥarām) to go with one’s pollution (wasākha) to places such as gardens where there was food or any sort of “God’s bounty” (niʿma).

But, as Mernissi (1975, 1–2) points out, Islam recognizes sexuality as a relatively positive fact of life, a strong motivating force that must find a legitimate outlet. She notes that no antipathy between spirituality or religiosity and carnality, no split between mind and body, exists in Islam as in Christianity. Men and women are enjoined to marry; not even members of the clergy are expected to be celibate. The Bedouins share these beliefs, and most Bedouin men and women marry. Within marriage, both men and women have rights to sexual satisfaction, and long-term refusal or inability to provide sexual services by either husband or wife is considered sufficient grounds for divorce.

Thus, Islam, in symbolizing the highest good in all Muslim societies, including the Awlad ʿAli, and in codifying aspects of sexuality and sexual behavior as threatening, contributes to the negative view of sexuality. However, the source of the force and tenacity of this attitude lies not in Islamic ideology, but in the tribal social-structural model, based on the priority of relationships of consanguinity and organized in terms of patrilineal descent. Sexuality, even in its socially legitimate and religiously sanctioned guise of marriage, although necessary for the reproduction of society and the perpetuation of lineages, does not rest easily within this framework. Only patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage fits this model, which is why it is the preferred and culturally ideal marriage form in much of the Middle East. Frequently practiced by Awlad ʿAli, patrilineal parallel-cousin marriage is legally sanctioned in the institution of “the claim to the daughter of the paternal uncle” (mask bint il-ʿamm), and it carries a positive affective tone.11 This form is ideal because it follows the patrilineal principle, subsuming the marital bond under the prior and more legitimate bond of kinship.12

Sexuality, together with the bonds it establishes between individuals, is not just a conceptual threat to the conceptual system that orders social relations, but a threat to the solidarity of the agnatic kin group itself. This threat, particularly to the extended patrilocal residential group, is often noted in the literature on similarly organized societies, from traditional China (Wolf 1972) to Zinacantan (Collier 1974). Collier (1974, 92) notes that in systems where resources are held jointly, the interests of in-marrying women are bound to be different from those of the men they marry and at cross-purposes with those of senior agnates, whose concern is the preservation of lineage unity. In-marrying women’s loyalties are to their children, not to their husband’s kin group. They may pressure to split the joint households of adult brothers in order to increase access both to resources and to the power accruing to the person at the top of the domestic hierarchy in an independent household. However, it should be noted that wives do not necessarily initiate moves to fission; often they serve merely as excuses or scapegoats for younger brothers wishing to escape their elder brothers’ authority and to seek independence, in contradiction to the explicit ideology of the solidarity of patrikin (Denich 1974, 256).

At marriage, men, too, develop competing interests, but to a lesser degree than women. Their children are part of their lineage, so any interest in them is consonant with lineage interests. But, as Riesman notes for the patrilineal Fulani, the sexual bond leads to the dispersal of the agnatic group.

The sexual bond, the bond that must not be evoked by uttering the partner’s name, detaches a man from his agnatic group by uniting him with his wife. And the more fertile this bond is, the more the man approaches true independence with respect to this group. . . . As a result, to the extent that women in their huts symbolize legitimate sexuality, hence the right to progeny, they are in fact a necessary cause of the dispersal of men. (Riesman 1977, 58)

Sexuality and marriage also threaten the authority and control of elder agnates, who represent the interests of the agnatic group. The Bedouins recognize the competing nature of sexual bonds and kinship bonds, as the following popular wedding ditties, referring to the groom on his wedding night, indicate.13

When he shuts the door behind himhe forgets the father who raised himkēf yrud il-bāb warāhyansā būh illī rabbāhHe reached your arms stretched on the pillowforgot his father, and then his grandfatherṭāl dhrāʿak ʿal l-imkhaddayansā būh wyansā jaddu

This challenge to the hierarchical relationship between providers and dependents, or elders and juniors, is at the heart of Bedouin attitudes about sexuality. When a woman leaves her kin’s residential sphere at marriage, their control over her must thenceforth be shared with her husband and his kin. When she bears children, her attachment to her husband’s group grows, competing with her loyalty to her own natal group, despite her continued membership in her own patrilineage and tribe. For a young man, as Peters (1965, 129–31) points out in reference to the Cyrenaican Bedouins, marriage undermines the exclusive authority of senior agnates by giving him a domain of authority of his own, however minuscule. Senior agnates, for their part, studiously ignore junior agnates’ weddings, subconsciously recognizing the threat such weddings pose to their authority. Similarly, among the Awlad ʿAli the groom’s father and elder paternal uncles are never among the men firing rifles to celebrate the engagement or marriage of a son or nephew, and the father never joins the group that fetches the bride. Needless to say, sexuality outside of marriage (rare indeed) intensifies the challenge to the control of senior agnates over their dependents.

The more closely individuals identify with the interests of the patricentered system, the more they perceive the threat to the system as a threat to their own authority. This even holds true in the relations between men and women. Sexual desire is an internal force that is difficult to master, thus representing a potent challenge to one of the keystones of honor, self-control. Succumbing to sexual desire, or merely to romantic love, can lead individuals to disregard social convention and social obligations intimately implicated in the honor-linked values, marking the failure of ʿagl—as we saw in the cases of men called idiots or donkeys. Sexuality can lead to dependency, which is inimical to the highest honor-linked value, independence. Men can forfeit their positions of responsibility as independent providers by coming to depend on women to gratify their sexual desire. Women, not to mention others, lose respect for such men, and may use this dependence to their own advantage, thus reversing accepted hierarchical relations between men and women.

At every point, the threat to the solidarity of the agnatic group and to the authority and control of its elders is counteracted by social and ideological strategies. Patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage is the logical strategy for defusing the threat of the sexual bond in this social system. In this case, the sexual bond does not violate the basic principles of the social order simply because the couple is already bound by relations of identity and closeness through their bond as kin. And since the term for patrilateral cousin extends beyond actual first cousins to include any patrikin of the same generation—hence, any members of the same tribe, as defined at various levels of segmentation—the range of marriages that need not be construed as challenges to the social system is quite broad. Also, the preference for endogamous marriages assures that many Bedouin women will be of the same lineage or tribal segment as their husband and his kin; these wives are not the “worms within the apple of a patrilocal domestic group,” as Collier (1974, 92) so graphically puts it, but individuals who share interests with their community of marriage.

The priority of the bonds of kinship over those of marriage are asserted and enforced in other ways. Bedouin women retain their tribal affiliation, their contact with their own patrikin, particularly brothers and fathers, and their reliance on their own kin for moral, economic, and social support. Rarely cut off from their own kin, they are never utterly dependent on their husbands, and, having alternative paths to support and respect, they rely less on a strategy of binding sons to themselves for security than do women in other patricentered systems, such as the Chinese (Wolf 1972). Their loyalties remain with their patrikin as well; thus, a woman’s kinsmen may demand that she leave her husband if they fight with him or with any member of his lineage.

The control of senior agnates over the choice of marriage partners is another means of limiting the threat marriage poses to the system. Families arrange marriages for young people. Love matches are actively discouraged, and thwarted when discovered. In much of the Middle East, the explicit ideology—that men arrange marriages—is contradicted by the influence women exert over marriage choices. Among Awlad ʿAli, although there was a great deal of variation in who arranged marriages, men seemed to take the lead in higher-status tribes and lineages, whereas women had more say in families of less importance or wealth. In any case, men certainly conducted the official ceremonial marriage and bride-price negotiations. Taking the decision out of the hands of the two people to be married bolsters the authority of the kin group over individuals and over the couple as a unit.

The predominance of kinship bonds is further reinforced by downplaying the married couple’s separateness and independence. The marital bond itself is not sanctified; it is dissoluble and not exclusive (at least for men). Divorce is common and fairly easy to obtain:14 of the fifty-three adults in the fourteen households that constituted the camp I lived in, eighteen, or approximately one-third, had been divorced at least once, five more than once. Divorce carries no stigma; divorced women easily remarry and command almost the same bride-prices as virgin brides. Polygyny is condoned, if relished less by women than men.

Even in terms of residence and economic power, the conjugal unit is barely allowed to exist in its early years. Most new couples live in extended households in which the patriarch controls resources. The new husband rarely has financial independence but works jointly with his brothers. The young bride receives gifts such as clothing not from her husband but from her father-in-law, who brings gifts to all the women in the household—his wives, daughters-in-law, daughters, sisters, or whoever happens to be living with him. In the past, except in very difficult circumstances, a new couple had a tent of their own, to which the bride was brought on her wedding day. It was pitched in front of the camp (traditionally a row of tents), and after the honeymoon week the rest of the camp moved forward to join the new tent. Nowadays, brides are brought to rooms that have been added on to the groom’s father’s house. In neither case was the conjugal household considered separate, for resources were not split and the new couple had no resources of its own.

On the level of ideology, every attempt is made to minimize the significance of the marital relationship and to mask its nature as a sexual bond between man and woman. Marriage is spoken of as a bond between groups, families, lineages, or tribes; stress is on the creation of affines (ansāb). The Bedouins never refer to marriage by the usual Arabic terms jawāz or zawāj, whose direct reference to pairing or coupling, hence private sexuality, they find crude and overly explicit. They prefer the euphemism bani il-bēt (“setting up a tent or household” or “building a house”), which simultaneously suggests the establishment of a household and the building of a lineage. This expression deflects attention from the significance of marriage as that which joins a man and woman and stresses its significance as that which establishes and contributes to the growth of kin groups.

The modesty code is the final strategy for undermining the bond of sexuality. If the threat to the social system can be experienced as a threat to individual respectability, then the social order will be reproduced by the actions of individuals in their everyday lives. This is precisely what happens with Awlad ʿAli. To achieve virtue, those most disadvantaged by the social system must suppress in themselves that which threatens the social system, especially in front of those who represent and who have most to gain in the system.

The modesty code minimizes the threat sexuality poses to the social system by tying virtue or moral standing to its denial. To overcome the moral devaluation entailed by less self-mastery and control over one’s own body and by closer association with that which threatens the social system, people must distance themselves from sexuality and their reproductive functions. For Awlad ʿAli, closeness to the “natural” force of sexuality provides an axis along which moral worth may be readily gauged. The more women are able to deny their sexuality, the more honorable they are.

This association is clear in ḥasham, the sine qua non of virtuous womanhood. To describe a woman as someone who taḥashshams,15 referring both to the emotion that motivates sexual propriety and to the acts that mark it, is the highest compliment. Women so described are those who act chastely, denying any sexual interests and avoiding men who are not kin. The modest woman admits no interest in men, makes no attempt to attract them through behavior or dress, and covers up any indication of a sexual or romantic attachment (even in her marriage). The woman who does not is called a “slut” (qḥaba) or a “whore” (sharmūṭa).

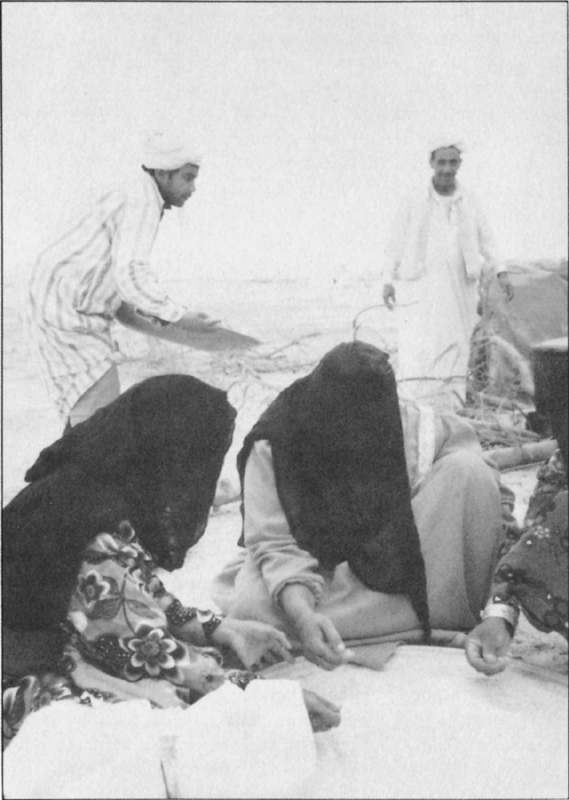

The surest way not to attract men’s attention is to avoid them. Although the exigencies of the division of labor and the nature of women’s work make seclusion impractical for Awlad ʿAli, women avoid men in other ways. The woman who taḥashshams does not let herself be seen by men unless it is absolutely unavoidable or unless, as with certain categories of men (described below), it is unnecessary to avoid them. She does not go to market and does not appear when guests or strangers visit her household. If contact is unavoidable, she veils. In addition, she acts and dresses so as not to draw attention to her beauty. Makeup is frowned on (except kuḥl), and her cherished long braids and gold earrings must be covered with the headcover (ṭarḥa). The modesty of Bedouin women’s dress has already been remarked. But everyone recognizes that modest dress and even veiling are no guarantee of modesty. Older women complained that younger women were not as modest as they had been: younger women’s veils were of thinner material, and worse, they raised their heads and talked to men through the veils—in short, they did not act correctly. As noted in the last chapter, the behavioral correlates of modesty are a variety of self-effacing and formal acts, including refraining from talking, eating, and laughing. To act immodestly in any of these ways in the company of men is interpreted as shameless flirtation. I was once taken to task by the adolescent girls in my household for having flirted with some men I was interviewing. Their evidence was that I had been animated, letting my face and eyes become too expressive.

Good women deny interest in sexual matters and deny their own sexuality. An important goal of the socialization process is to teach girls to do this. One little girl who laughed at the enormous size of a donkey’s genitals was reprimanded by her older sister, “Let’s have no quḥub [whorishness]!” Another girl confided in her uncle’s new wife, “To tell you the truth, I don’t even know what this love is. I hear about it in songs and hear about this one giving her necklace and that one her ring, but I don’t know what they are feeling.” The older woman responded approvingly, “That’s my girl.” Adolescents are criticized for any indication that they wish to marry. If they get carried away singing and clapping at a wedding or hover as the defloration is taking place, their mothers taunt them, “What are you so interested in? Are you looking forward to your own wedding day?”

Much socialization takes the form of humorous teasing, as in the following incident I witnessed. Western-style negligees, quite common in urban areas, had just begun to be peddled in the desert areas. Two adolescent girls, generally intrigued with urban accoutrements, were enthralled and purchased frilly nightgowns for their trousseaus. Their grandmothers were outraged, and one demanded that her granddaughter bring her the negligee as she sat with a group of women. She showed it to the visitors, asking if it was not the most shameless thing they had ever seen, and then she pulled the sheer, lime-green nightgown over her bulky dress and danced provocatively around the room. When she threatened to go outside to show it to the men, the women wailed with laughter and dragged her away from the doorway. The other grandmother then proposed taking a match to the negligees. Finally the chastised girls were told to try to return them to the peddler.

The girl who taḥashshams cries when she hears that someone has come to ask for her hand. The good bride screams when the groom comes near her and tries to fight him off. She is admired for her unwillingness to talk to the groom or answer any of his questions, as reported by the young men who listen outside the window on the wedding night.

Even married women must deny any interest in their husbands, much less other men. One young woman reported that her older cousin had pinched her between the legs when she caught her peeking at an attractive man through the side of the tent. People accuse a woman of lacking ḥasham if she indicates that she desires her husband sexually, especially when she reaches middle age or has grown sons. Stories of older women who get pregnant meet with mild signs of disapproval despite the admiration for fecundity. One woman in our camp caused quite a stir when she made her older children sleep with their grandmother to indicate her availability to her estranged husband; after he returned she was radiant and even joked that she should be given bridal gifts (see Ṣafiyya’s story in chapter 7). An angry woman will insult another by referring to the size of her genitals (the presumption being that the larger the genitals the more voracious the desire).

Modest women mask sexual or romantic attachments. Women rarely use their husbands’ names but refer to them simply as “that one” (hadhāk) or, if they are affectionate, “the old man” (shāyib) or “the master of my house” (ṣāḥib bētī). At least in front of others, they are formal and distant with their husbands, showing no public affection and acting terribly embarrassed if it is shown toward them. Although quick to admit the ubiquity of jealousy, the Bedouins do not respect a woman who lets on that she resents a co-wife whom the husband prefers or spends more time with. They consider such resentment an indication of excessive desire or interest in the husband. To maintain reputation, most women couch objections to co-wives or dissatisfaction with polygynous husbands in material terms, complaining about inequalities in the distribution of material rather than emotional favors.

The importance of the denial of sexuality to women’s modesty is clear from this discussion of the good woman. But why is the denial of sexuality more crucial to women’s virtue than to men’s? In its ordinary aspect, as deference for providers and social superiors, ḥasham is an avenue to honor that is equally crucial for the essentially dependent female as for those males who are dependent for whatever reason and duration. Yet in its other aspect, as sexual shame and modesty, it is more essential to women than to men. As we saw earlier, men’s honor also rests on their mastery of “natural” passions and functions, including sexuality; but because men are less organically linked to sexuality, they are correspondingly less pressed to deny it. The primary forces men must master in themselves are fear, pain, hunger, and dependency. Thus, only insofar as sexuality leads to dependency must men deny it, and they can do so by condemning and avoiding its representatives, women. Women are more closely associated with the sexuality that threatens the whole male-oriented social order through their reproductive activities and their inability to conceal sexuality because of pregnancy. This close association means that they represent not the embodiment of that order, as do the mature men at the top of the hierarchy, but its antithesis. It is therefore more incumbent on women to deny their sexuality in order to assert their morality.

It is important to note, however, that the devaluation and denial of sexuality implied by ḥasham are not equally necessary to women’s honor in all social contexts. Ḥasham is critical in public and in situations where women interact with hierarchical superiors or strangers. The situational character of ḥasham is marked by the preposition it takes—min, “from.” People do not expect women to act modestly or to experience shame about their sexuality in interactions with peers and close associates. In same-sex groups of women who are close kin, age-mates, or familiar for other reasons, conversations are often bawdy, and Bedouin girls and women do not seem priggish or delicate. Many interactions between women and certain categories of men—nephews in particular—are also extremely relaxed and intimate; as long as a woman is chaste and acts modestly with other men, her allusions to sexual interests meet only with bemused tolerance. For example, a lively and funny woman who had left her husband temporarily to stay with her mother (suffering because her only son was in prison) joked, “I’ve been five months away from ‘the old man,’ not a taste! I left him to another woman. The least they [her mother’s household] could do is give me a little tip.” Her cousin, relating this incident to her friends back home, laughed and commented affectionately, “She has no shame [mā taḥashshamsh]!” This was not a condemnation.

In public women avoid their husbands, but in private they may be affectionate and familiar. The woman with whom I lived claimed that she had no objection to eating with her husband but refused to do so when other women were around. She looked very embarrassed when her husband tried to put his head in her lap while I was sitting with them, even though I had lived with them for over a year and knew them both quite well. The formality and distance between husbands and wives is exacerbated when men, particularly elder men, are present, but even in front of younger men or children men mask affection for and interest in their wives. People say that a man’s children won’t taḥashsham from him if they witness his affection for their mother; attachment to women is interpreted as dependency, which compromises a man’s right to control and receive the respect of his dependents.

The situational character of sexual modesty is the clue to its meaning. In the last chapter I showed that Awlad ʿAli conceptualize ḥasham as both the shame of lesser moral worthiness (the emotion of embarrassment/shame/shyness) and voluntary deference for those of greater moral worth who have control over one (expressed in acts of modesty). Thus, it is relevant only to specific social contexts—interactions with superiors. I now argue further that sexual modesty in Bedouin society is tied to the same specific contexts and can best be understood as an aspect of deference. (This interpretation allows sense to be made of the otherwise inexplicable patterns of Awlad ʿAli women’s veiling, as I will show in the next section.) Because men of honor, those responsible for dependents, embody the values of the system and also represent it and bear responsibility for upholding it, sexuality is a challenge not only to the system but to these men’s positions as well. To express sexuality is therefore an act of defiance, and to deny it an act of deference.

By showing sexual modesty before these representatives of the male system, those lower in the honor-based hierarchy express their respect for the social system. When I asked one man why women taḥashsham, he replied, “From respect [iḥtirām] for their tribe [lineage], their husband, and themselves.” Unable themselves to identify with the system through the embodiment of its highest values, women, as well as young and poor men, defer to those who do, thereby gaining for themselves the honor garnered by those with ʿagl, the social sense to conform to the social system. Not surprisingly, the woman who taḥashshams is also described as ʿāgla.

This association of sexual modesty with respect for the more responsible is reflected in the way the Bedouins conceive of virtuous women. The ideal woman who taḥashshams is called “the daughter of a man” (bint ir-rājil). When I asked girls why a young bride cries when someone comes to ask for her hand, they answered, “So everyone will know her father is a man and that he raised her.” On the question of premarital sex or elopement, the most egregious violations of the modesty code, the same connections are asserted. Whenever I questioned women about the motivations of girls who engaged in premarital sex or eloped, they explained, “They are sluts who don’t care about their fathers and aren’t afraid of their kinsmen.” As we saw in the last chapter, deference and fear are extremely close conceptually and are often used interchangeably in Bedouin utterances.

This analysis of the relationship between sexual modesty and deference for those more responsible allows us to reinterpret a phenomenon that has long puzzled observers of Arab social relations: the dishonor brought on kin by a woman’s sexual misconduct. In part, this sharing of dishonor can be attributed to the identification with kin described in chapter 2. But shared social identity does not explain why kinsmen are more dishonored than the woman herself or why killing her wipes out the shame. If we understand women’s chastity as an aspect of deference, however, we can see how Bedouins interpret infractions as acts of insubordination and insolence. Because men’s positions in the hierarchy are validated by the voluntary deference shown them by their dependents, withdrawal of this respect challenges men’s authority and undermines their positions. In the eyes of others, a dependent’s rebellion dishonors the superior by throwing into question his moral worth, the very basis of his authority. Thus, a woman’s refusal to taḥashsham (deny her sexuality) destabilizes the position of the man responsible for her. To reclaim it, he must reassert his moral superiority by declaring her actions immoral and must show his capacity to control her, best expressed in the ultimate form of violence.16

The greater dishonor of adultery for the woman’s kin than for her husband can also be understood in these terms. If sexual immodesty is an affront to those who depend on a woman for validation of their authority, then those most responsible for her would be most dishonored. Her husband’s authority over her is always limited by the primary authority of her kin in a system so thoroughly patrilineal that women, even after marriage, retain their ties to, identification with, and dependence on patrikin. As Meeker (1976) points out in a brilliant discussion of honor in the Middle East, Arabs contrast in this respect with the Black Sea Turks, among whom the husband gains full authority for his wife at marriage; he is thus correspondingly more dishonored by her infidelities and bears the responsibility for her punishment.

The best test of the validity of this interpretation of ḥasham—that denial of sexuality is equated with deference—is its power to explain the pattern of women’s veiling. Bedouins consider veiling synonymous with ḥasham, or at least a fairly accurate index of it. Symbolizing sexual shame as it hides it, veiling constitutes the most visible act of modest deference. When the new bride quoted in the last chapter asked her young friends, “Who taḥashshams from whom in the community?” she got a list of the men for whom particular women veiled.

Veiling is both voluntary and situational. Awlad ʿAli view it as an act undertaken by women to express their virtue in encounters with particular categories of men. They certainly do not perceive it as forced on women by men. If anyone besides the woman herself has responsibility for enforcing the veil’s proper use, it is other women; they guide novices (brides) along, teasing young women for veiling for men who don’t deserve their deference and criticizing them for failing to veil for men who do.

Although Anderson (1982, 403) correctly notes that “veiling refers actions to a paradigm of comportment in general rather than to chastity in particular,” he overstates the case in his effort to combat prevailing misconceptions about its exclusively sexual motivation (see Antoun 1968; Mernissi 1975; Dwyer 1978).17 Veiling communicates deference, but its vocabulary is that of sexuality or chastity. The folktale of mother-son incest recounted earlier makes that point, as does the fact that Bedouin women do not veil for other women no matter how identified with the lineage and social system they are. The most compelling piece of evidence is the timing of veiling in the life cycle. Girls start veiling only at marriage, when they become sexually active, and women gradually abandon the practice as they pass menopause. When I asked one close woman friend why virgins did not veil, she laughed, made the obscene gesture of coitus, and asked, “Hasn’t a man entered the married woman? She taḥashshams.” Exceptions to proper veiling prove the rule. When I asked a widow in early middle age why she did not veil, she answered, “I’m not buying or selling [the reference being to marriage and sexuality].” Those women described earlier as “like men” or “living like men” also veil less often than women living with husbands, confirming this interpretation of the meaning of veiling as that which covers sexual shame.