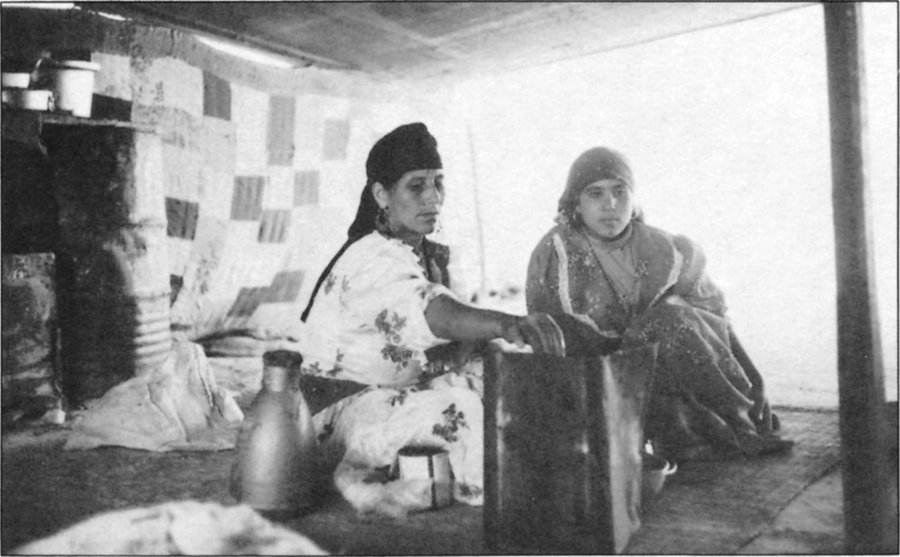

Woman and her niece making tea on a kerosene burner with a windbreak made of an old olive oil tin

Poetry is not, of course, the only medium in which Awlad ʿAli express sentiment and make statements about their experiences in personal life; they also do so in ordinary language and plain behavior. Yet, as suggested in the introduction, individuals use poetry in their everyday lives in a striking way: to express special sentiments, sentiments radically different from those they express about the same situations using nonpoetic language. Thus, each mode of expression can be considered a distinct discourse on personal life. Discourse here refers not simply to linguistic form, as in the distinction between formalized and everyday speech acts.1 Rather, I use the term more in the sense that Foucault (1972, 1980) uses it, to mean a set of statements, verbal and nonverbal, bound by rules and characterized by regularities, that both constructs and is patterned by social and personal reality.2

This use of the term discourse as a shorthand for a complex of statements made by numerous people in different social contexts is justified by the existence of a pattern in the sentiments expressed in the two media. People often turn to poetry when faced with personal difficulties, but the constellations of sentiments they communicate in response to these difficulties in their poems and in their ordinary verbal and nonverbal statements overlap very little. The discourse of ordinary life for those confronted with loss, poor treatment, or neglect (among the most frequent elicitors of poetry) is one of hostility, bitterness, and anger; in matters of lost love, which will be explored in the next chapter, the discourse is one of militant indifference and denial of concern. Poetry, on the contrary, is a discourse of vulnerability, expressing sentiments of devastating sadness, self-pity, and a sense of betrayal, or, in cases of love, a discourse of attachment and deep feeling.

Before analyzing the intriguing incongruities between the two discourses, I want to lay out the contours of the poetic and mundane discourses by presenting a few cases that illustrate the pattern of individual responses to loss and show how widely the two discourses ramify in social life. It will become clear that the mundane discourse is explicable by reference to the ideology of honor and modesty, whose logic has already been uncovered; the sentiments people express in ordinary life are informed by and consonant with the ideals of this moral code. (Explication of the poetic discourse will be the subject of the final chapter.)

A case of rejected love illustrates the pattern of dual responses and introduces the tension between the honor code’s ideals and emotional entailments and those of poetry. In chapter 3 (see p. 94) I presented the case of Rashīd, the man whose bride ran away. His inability to mask his dejection from his close kin had seriously jeopardized his right to respect. But outsiders and even many in the camp who knew him less well were unaware of these signs of his attachment to her, and hence of his dependency and weakness. What they saw was another response, supported and encouraged by his kinsmen and friends.

Almost immediately after the woman fled, Rashīd looked for someone to blame. In the community, the question on everyone’s lips was “Who ruined her [man kharrabhā]?” meaning something like, Who made her unhappy or poisoned her thoughts? Rashīd, along with his brother, undertook an intensive investigation of the events preceding her departure. When they had eliminated the possibility of some woman or child in the household having upset her, they began to consider sorcery as an explanation. Rashīd was convinced that his senior wife must have been responsible. A visit to the local holyman (fgīh) to divine the reason behind the bride’s act confirmed this suspicion, and the hushed accusation sped through the community. In the face of opposition from many of the camp’s women, Rashīd persisted in blaming his first wife, angrily refusing to talk to her or visit her and sleeping alone in the men’s guest room.

Rashīd’s kinsmen, who viewed this as a family, not a personal, crisis, also reacted with anger. Although some suspected the senior wife and shunned her, others directed their anger at the bride. They took her flight as an insult to the lineage, and many echoed the sentiments of Rashīd’s paternal first cousin, who defiantly sang a traditional wedding song to the effect that there were many more women where that one had come from. The men blustered, “If she doesn’t want us, she can just have her divorce, and we won’t even ask for the bride-price back.”

After some negotiation and pressure from her family, the bride agreed to return. A day or so later, I was talking privately with Rashīd. I asked him how he felt and he answered with a statement about how everything was all right because “the woman” knew that she had done something wrong. I then asked disingenuously if he ever recited poetry. He looked embarrassed, because I had mentioned something that was not appropriate in conversations between men and women, but offered the following poems on the assumption that I would not realize their significance.

Cooking with a liquid of tearsat a funeral done for the beloved . . .blūlhum ghēr dmūʿil-khāṭr ʿazā dār fil-ʿalam . . .Her bad deeds were wrongs that hurtyet I won’t repay them, still dear the beloved . . . 3ʿazīz lil-kfā mā hānsayyāthā khaṭā wājʿātnī . . .

Any doubts I harbored about whether these poems expressed his personal sentiments regarding the situation were put to rest a few days later. It was evening, and Rashīd sat with his returned wife. He asked me to join them, requesting that I bring my notebook, and he instructed me to read them “the talk of the other day.” I realized he was referring to the poems he had recited for me. As I read them aloud, he seemed embarrassed and acted almost as if he had never heard them before. He looked blank when I asked him to explain them. The next day his wife confided that these poems were about her. He had used this indirect means to communicate his sentiments to her.

The poems revealed sentiments of grief and pain caused by the loss, a far cry from the anger and the wish to attribute blame that his public accusations of sorcery had communicated. When I shared these poems with some of my women confidantes, they were touched. Yet these were the same women who had condemned Rashīd as foolish or unmanly when he had earlier betrayed sadness over his bride’s departure and expressed his desire to have her back. Their differing attitudes toward statements made in poetry and those in ordinary interaction suggest that poetic revelations are judged by different criteria than are nonpoetic expressions.

The same dual pattern characterized the responses of Mabrūka, Rashīd’s senior wife, to the events of this marriage. When she first got wind of the sorcery allegations, she responded angrily and threatened to return to her kinsmen and demand a divorce. She also made bitter jokes about her “magic,” where she obtained it, and how powerful it was. For instance, when she sent a special pot of food to one of the other women in her co-wife’s household, she sent it with a message warning them to beware—the food might have “something” in it, a reference to magical potions. But two poems she later recited referred to this incident in a different way. The first indicated how wronged she felt by the accusation. The second conveyed her sense of isolation and loneliness in the community, as visiting is both essential to maintenance of social relationships and viewed as one of life’s great pleasures.

They slandered me then found me innocentnow the guilt must fall on them . . .ithimū khāṭrī bagwālṭalaʿ barā wdhnūb ādkadhū . . .I could not make my visiting roundsthe married man’s house was full of suspicion . . . 4ʿalēh mā gdirt njūltammat birībtu bēt il-ghanī . . .

A clearer illustration of the dual patterning of the expression of sentiment was her early reaction to the news of the marriage. Mabrūka’s immediate response was to blame her brother-in-law for the decision, suspecting him of having encouraged his brother to take a second wife so the lineage could have more children. Although she had been close to his wife for fifteen years, she stopped visiting her household and refused to help her with the major project of sewing a tent, even though all the other women in the community contributed their labor. When presented with the customary wedding gifts due the first wife, she threw them on the ground and refused to accept them until her sister-in-law begged her to.

She justified her anger by the blame she placed on her brother-in-law, some material injustices, and violations of conventions in the handling of the marriage. For example, she refused to accept her wedding gifts because they were not identical to those given to the bride—a bone of contention was a pair of Western-style sandals the bride had received, whereas Mabrūka had not been offered any shoes. She refused to attend the wedding because the new bride was not going to be brought into her household but would be set up in a house with her husband’s brother and his wives—not customary procedure, as she pointed out to everyone. When I asked how she felt about the wedding, she remarked on these injustices and claimed that she was only angry because things were not being done correctly.

Shortly before the marriage took place, I was sitting with her and a group of her daughters and nieces, when, with an initial prompt from me, she began to recite poems, one after another. These indicated a rather different set of responses to the event and another emotional tone. The following sample, only a few of a long string, represents a range of sentiments she expressed that day. In the first poem, she described the sensation of being overwhelmed not just by anger but by “despair” (yās), the sentiment of extreme despondency that figures heavily in ghinnāwas:

Held fast by despair and ragethe vastness of my soul is cramped . . . 5msāk yās wghēẓbarāḥ khāṭrī dׅhayyigibhun . . .

Another poem expressed her sense of abandonment through metaphors of nature:

Long shriveled from despairare the roots that fed my soul . . .shjirat khāṭrī min il-yāszamān mōta ʿurūghā . . .

In another she appealed to her absent husband for some consideration in response to all she had given him. This poem used imagery of ships and harbors, which I could not carry into the translation:

I took upon myself your lovekindly make me a place to rest . . .shaḥanit khāṭrī bghalākbifdׅhūlak marāsī dīrlī . . .

Related to this theme was another poem suggesting she was being neglected in her suffering by someone who had the power to cure her. Her husband could have relieved her by paying attention to her and trying to please her.

They left me to sufferwise ones, they had but withheld the cure . . .tarākū ʿalē mashkāyʿaggāl lū bghaw dāy māsakun . . .

These early poetic responses to the prospect of her husband’s second marriage expressed not so much the anger and blame evidenced in the rejection of her wedding gifts and in her constant threats to leave as misery and vulnerability. Toward the end her poems took a different turn, providing commentary on her angry behavior:

She raised her pricesclosed her door and refused to provision them . . .ʿallat sʿārhā ʿan-nāsgfilat bābhā mā mayyarat . . .

and finally:

Better had they calmed mebut since they opposed me I opposed them . . .lū kān hāwadūnī khērmin ḥāsh ʿānadū ʿānadithum . . .

Anger and blame are such common responses that people act carefully to avoid any possibility of being blamed. The fear of being blamed for “ruining” the bride again, or for making anything else go wrong in the marriage, led to a great unwillingness on the part of many community members to visit the household she lived in. The same type of fear underlay the absence of another woman’s maternal kin from her husband’s marriage to a second wife. They thought it likely their kinswoman would opt for a divorce, since she had only been married a year and was young, beautiful, and childless, hence highly marriageable. If she left, however, they would most likely be blamed for putting the idea into her head. Attributing blame when hurt is a response learned early in life: when young children come crying to their mothers, they are more likely to be asked, “Who did it?” than “What’s the matter?”

There is one alternative to anger in cases of loss other than death, namely, a show of indifference or defensive denial of concern. This behavior is particularly characteristic in matters of love (see chapter 7), but it also applies in the most trivial of loss situations. For example, Awlad ʿAli consider long thick hair one of women’s most treasured assets and a mark of beauty. Its loss would thus be significant. Someone observing a woman combing her hair might remark that she was losing a great deal of it, a common enough occurrence given women’s generally poor health. She would probably respond with the phrase “in shāllah mā yrawwiḥ,” literally “God willing it won’t return,” but in idiomatic translation, “Good riddance” or “May it never come back.” The same phrase greets a child who disobeys or who defiantly refuses to come when called. People also speak of misplaced objects and memories of past pleasures in the same way.

A show of indifference can be a sign of stoic acceptance of a situation over which an individual has little control. Separations represent the type of loss to which stoic acceptance is the rule. The poems of separation, however, were among the most numerous and poignant people sang, expressing the sentiments of sadness and longing and, through metaphors of illness, the effects of the loss. A few examples suggest the range. The following one implies that the natural world mirrors the dark inner state of the person left behind:

cloud cover, no stars and no moon . . .laylat frāg ʿazīzghṭāṭ lā njūm wlā gmar . . .

Another describes through metaphors drawn from physiological experience the painful effects of separation. Blindness comes from excessive weeping.

Separation from intimates is hardfrāg ish-shgīg ṣaʿībil-galb ṣāf wil-ʿēn ghāwnanat . . .

A third alludes directly to the effort to be stoic in partings:

Strong-willed in the send-offthe self did not cry until they parted . . .shdīd ʿazm fit-taṣmīlil-ʿagl mā bkā nīn fārgū . . .

A more defensive denial of concern can be the response to rejections or slights, as one woman’s visit to her natal community illustrates. Migdim was a woman in her sixties, the favorite paternal aunt of the core agnates of my community. The old woman often came to visit; she would stay a week or two or as long as she could be persuaded, spending a few days in each of the core households to divide her time among her many nieces and nephews. One night she came to stay in the household I was living in, where her niece Gaṭīfa, married to her nephew, the Haj, and another nephew and his wife lived. Gaṭīfa, always solicitous and happy to see Migdim, invited her to sleep in her room, since her husband was away. But just as they were bedding down for the night, the Haj returned unexpectedly from his trip. Feeling uncomfortable ejecting him from his room and wife, the old woman insisted she would move. I offered her my room, which was next to the room of her other nephew and his wife of several months. I stayed behind to speak with the Haj, and Migdim and her grandnieces went to my room, where the other man’s wife offered them the use of her blankets and pillows. But then her husband returned and complained about the missing blankets; he was also irritated because the children would be in his section of the house. So Migdim moved again, this time to an empty room where she spent an uncomfortable night with practically no bedding.

The next day, Migdim was unusually silent. She said nothing about her trials of the night before. But then she recited some poems that showed how she felt about the disgraceful mistreatment she had received at her young nephew’s hands. These poems convey surprise and pain at his inconsiderate behavior.

I never figured you’d dowrongs like these, oh they hurt . . .mā niḥisbūk tdīrsayyāt kēf hādhēn yaṣʿabū . . .Forced by drought in the landto seek refuge among peoples of twisted tongues . . .rmāna jdab l-awṭānʿalē nās ʿāwja lghāthum . . . 6

She explained the last poem to me. In search of pasture, people had to go to a new area where they found alien tribes whose language they could not comprehend, “people who weren’t people.” She was referring to her expulsion of that evening and the incomprehensibility of her nephew’s disrespectful and inhospitable behavior. By drawing attention to it in ordinary social interaction, she would have admitted her humiliation. Instead, she had appeared to ignore it or not to care, a strategy that, given the code of honor, had the same effect of saving face as fighting back in anger would have had. She confessed how wounded she felt only in her poems.

Death is the ultimate loss. As with other losses, Awlad ʿAli individuals respond to bereavement differently in ordinary public behavior and in the formulaic medium of poetry. But in bereavement, individuals also express their sentiments through a ritualized funeral lament called “crying” (bkā) that is structurally equivalent and technically similar to poetry. Significantly, this form is a vehicle for the same sorts of sentiments poetry carries, for reasons that will become clear in the final chapter.

The following three cases convey the typical cultural patterning of reactions to death and suggest the cultural terms in which death is interpreted by Awlad ʿAli. In everyday language and behavior, people react to death with anger and blame, sentiments closely associated with the impulse to avenge deaths, mirrored in and buttressed by the institutionalized complex of feuding described in detail by Peters (1951, 1967). However, in poetry and in “crying,” the same angry individuals communicate sorrow and the devastating effects of the loss on their personal well-being.

The first case concerns a family’s response to the fairly sudden illness and death of a girl of about seventeen. Although a physician pronounced the cause of death as cancer, the family accused the man who had frightened her by firing his rifle into the air while she was grazing some goats nearby of having caused her death. It was after that incident, her family claimed, that she had sickened. Their angry dispute with this man wore on for months until it was finally brought to a tribal court, where the girl’s family demanded blood indemnity, the traditional recompense for a killing within a tribal segment (see Peters 1967).

Yet at her funeral, and for over a month after, her death was met with much “crying,” the quintessential act of ritual mourning. At the news of a death, Awlad ʿAli women begin a stylized high-pitched, wordless wailing (ʿayāṭ). Then they “cry.” “Crying” involves much more than weeping; it is a chanted lament in which the bereaved women and those who have come to console them express their grief. Beginning with a phrase whose English equivalent is “woe is me,” the bereaved bewail their loss in “crying.” Those consoling the bereaved bewail the loss of a deceased person dear to them, usually a father or mother. Like the singing of poems, the chant takes the form of a short verse of two parts, the words repeated in a set order following a single melodic pattern. The special pitch and quavering of the voice, more exaggerated than in singing, along with the weeping and sobbing that often accompany it, make this heart-rending. The Bedouins do not equate “crying” and singing, but they recognize the resemblance when questioned. The two are structurally equivalent, both being expressions of sadness that draw attention to the mourner’s sorrow and bereavement.

Generally, men do not “cry,” although they sometimes weep silently; in this case, however, even the girl’s brother was said to have “cried,” attesting to her family’s uncontrollable grief. As a rule, men offering condolences greet the bereaved with a somber embrace out of which others must pull them. Men counsel the bereaved relatives to “pull yourself together” (shidd ḥēlak) and console them with pious references to God’s will and goodness. The only exception to men’s general avoidance of “crying” is the ritual lamenting undertaken by descendants of local saints at the annual festivals at the tombs of the saints or holymen. Men of the saintly lineage sing “poems” of their forefather in a quavering voice as they move from tent to tent, blessing those who have come to pay their respects and cursing those who cross them. People describe this singing as “crying” over the saint.

Another case, this time the death of an old woman, also provoked a heated response among her kin. Shortly after returning to her husband’s camp following an extended visit with her kin, the old woman died suddenly in the middle of the night. Her paternal relatives rushed to the camp, where they wailed and “cried” for two days, consoled her daughters, and were consoled for their loss.

The mourners returned to their own community angry, furious that her husband had behaved rudely to them and blaming him for her death. Some were convinced that the shock of hearing the news that he planned to marry another wife had brought on her death; others insinuated that the man had actually strangled her. The most vivid description of the old woman’s death was recounted by one of her nieces, a dramatic storyteller. In animated tones, she described how she had arrived in the aunt’s camp to find that her aunt’s body lay where she had fallen, the legs exposed and the face barely covered by her veil. No one had prepared her in proper Muslim fashion, placing drops of water in her mouth and tying her jaw shut. Throwing herself on the floor of the tent and letting her tongue hang out and saliva drool from the side of her mouth, the niece mimicked the awful state in which she had found her aunt. She recounted how she had scolded the people there, “What is the matter with you? Haven’t you ever seen a corpse before? At least you could treat her as decent human beings would. You could have covered her, shown her a little respect!” She then told how she had assisted the women in preparing the corpse for burial and how she had ordered her kin to provide a decent shroud to replace the inferior one the husband’s kin had provided. She personally was absolutely convinced that her favorite aunt had been strangled and that the husband was the culprit.

The senior agnate (and informal leader) of her paternal kin’s community had been traveling when the news of the old woman’s death arrived. By the time he returned, everyone else had already come back from the funeral. Informed of the death, he interviewed the men and women who had attended about what they had witnessed. At their descriptions, he kept exclaiming, “Damn him!” and muttering, “We’ll make him swear the oath!” He was referring to the ultimate recourse in determining guilt, the swearing of an oath at a saint’s tomb by the accused and his kin. But when he went to question the old woman’s daughters and other witnesses in the husband’s camp, he determined that there had been no trouble between her and her husband and was satisfied that she had died of natural causes. The furor subsided, and people began to concede that she might have died of a broken heart caused by the recent death of her only son. Nonetheless, the initial reaction had been one of angry accusation, balanced by the mournful “crying” of the funeral.

The third case is the most telling. This reaction to a homicide shows explicitly how the manifest anger and desire for revenge on the part of the murdered man’s kin are counterbalanced by the terrible sense of suffering revealed not just in “crying” but also in singing or reciting poetry.7 This case differs from the other two in that there was genuine cause for anger and someone who deserved blame. The killing of the youngest adult man in the group of agnatic kinsmen who constituted the core of the community had occurred seven years before my arrival. He had died from wounds inflicted by a couple of men from another tribe, who had provoked a fight in retaliation for an earlier beating he had dealt a kinsman of theirs. The event was described to me in vivid detail numerous times by various members of the group. The initial reaction to the news of the fight was always described in the same way: everyone, women and children included, rushed toward the hostile group’s camp, throwing rocks and wailing. The young man was still breathing when they found him. The men took him to the hospital in Alexandria, where he died a few days later. By all descriptions, the grief and ritualized mourning that followed were extraordinary and prolonged.

There was not only grief, but also a great deal of anger, directed at the family of those responsible and at others as well. For example, two subsections of the murdered man’s tribe officially split over this incident, because one group urged a peaceful reconciliation and the acceptance of blood indemnity three years after the killing, whereas the other recognized that the offended party was entitled to revenge. Hostility still flared up between these groups on various pretexts during my stay. Meanwhile, the murderers’ group had escaped to Libya, where the victim’s group tried to track them and had even made one unsuccessful attempt to avenge the murder. After the attempt, the avenging group let themselves be persuaded to undergo the reconciliation procedures, and they declared their forgiveness publicly. But this was only a tactic to flush out the offending subsection; they were biding their time, hoping the other group would let down its guard and give them the opportunity to take their revenge. People cursed whenever the name of the offending group was mentioned.

The poems the close relatives of the murdered man sang revealed another set of sentiments besides anger and the desire for revenge. All suggested the suffering the death had caused. Three themes characterized the poems: sleeplessness, associated in traditional Bedouin poetry with weeping and sorrow; illness, in folk psychology a consequence of any negative emotions; and “despair,” the word connoting apathy, hopeless misery, or extreme sadness.

The first poems I heard about the death were two by the elder paternal cousin of the victim. The first suggested restless search, perhaps for the object of revenge (and thus some anger); the second evoked only sad memories that intruded.

no happy sleep is his . . .yṭūla ḥdūd mnāhwlā bāt fī nawm hanī . . .Caught by a memory unawaresbrought tears in the hour of pleasure . . .khṭūra ʿalēh ghaflātbakkā l-ʿēn fī wān iṭ-ṭarab . . .

The victim’s mother recited a poem that alluded to her inability to forget and the sleeplessness her memories and grief brought:

Dear ones deprive me of sleepjust as I drift off, they come to mind . . .in-nawm ḥarramō ʿizāzin jānā yjūnā fawwalu . . .

Metaphors of illness abound in the poems of various other kinsmen and kinswomen. Yet the poems of men and women seem to differ. Another paternal first cousin echoed his brother’s sentiments, likening his suffering to a wasting disease from which he cannot recover until the death is avenged (the bones being those of the object of revenge).

wanted bones, repayment would release him . . .ydׅhāmar tgūl silīlṭalīb ʿaẓm fī dēn salak . . .

The victim’s sister sang a poem referring to the ill health resulting from the loss:

You left me, oh loved one,unsteady, stunted, and unhealthy . . .khallēt yā ʿazīz il-ʿēntmūj lā nimā lā ʿāfya . . .

The victim’s widow recited several poems late one night. Her closest friends were surprised, saying they had never heard her recite poetry before. These were two of her poems:

Ill and full of despairshow me what medicine could cure this malady . . .illī marīdׅh fīh yāsātwarrūnī duwā dāhā asmu . . .Drowning in despairthe eye says, oh my destiny in love . . .il-ʿēn ghārga fil-yāstgūl yā naṣībī fil-ghalā . . .

The despair to which she referred also appeared in the poems of a close kinswoman:

brought by despair and no other . . .il-ʿagl fīhā ʿadhāb shdīdmin l-yās wlā ghēr yā ʿalam . . .Forgotten not a single dayjust a patient mastering of despair . . .il-ʿagl mā nsīhum yōmṣabrā mghēr dālī yāshum . . .

These poems give voice to the anguish and pain the death caused, in the form of such symptoms as physical suffering, crying, disrupted sleep, brooding, and a sense of the presence of the dead, as well as apathy and despair.8 In contrast to the ordinary discourse, they barely speak of anger and vengeance.

The sentiments expressed in ordinary public interaction are, I would argue, those appropriate to what could be called a discourse of honor, their consistency attributable to the fact that they are generated within the context of the dominant ideology described in the first half of this book. In chapter 3 the virtues of a person of honor were outlined as those related to autonomy. The ideal person among Awlad ʿAli is the “real man,” the apogee of control who manifests his independence in his freedom from control by others and his strength or potency in his unwillingness to submit to others. He commands respect because of his high degree of self-control, physical and emotional. These ideal characteristics are valued by all, although differentially realized, and realizable, by individuals and social categories in Bedouin society. Except in direct interchanges with superiors, where deference is more highly valued, even women are expected to act in terms of these honor-linked ideals.

Only certain sentiments would be appropriate to self-presentation in terms of these ideals. Because weakness and pusillanimity are anathema, individuals strive to assert their independence and strength through resistance to coercion or through aggressive responses to loss. The prime sentiment of resistance is anger, which is focused into blame of others. An alternate strategy for asserting honor is defensive denial of concern, hence of the very existence of an attack. As Bourdieu (1979, 108) notes, “non-response can also express the refusal to riposte; the recipient of the offence refuses to see it as an offence and by his disdain . . . he causes it to rebound on its author, who is thereby dishonoured.” In the examples, this response arose only in cases of offenses by social inferiors, as with Migdim, or, as we shall see, in love. Like outward-directed defenses against the imposition of the will of others on the self, the third alternative of stoicism is consonant with the ideals of honor. To admit that one is wounded or deeply affected by the loss of others is to admit a lack of autonomy and self-control, a dependency through vulnerability. These are the attributes of the weak, of the young, the poor, and the female. Thus, by responding to loss with anger and blame or with a denial of concern, individuals both live in terms of the honor code and dramatize their claims to the respect accruing to the honorable.

In a similar way, the ideology of honor provides the guiding concepts behind responses to that most radical of loss situations—death—at least in routine social interactions and communications in the nonpoetic modes. It seems reasonable to assume that a concern with autonomy and pride would predispose individuals to interpret situations of loss as personal affronts or attacks. Resistance is the honorable response to an attack, and anger is the sentiment, whether perceived as motivation or concomitant, compatible with resistance. By responding with anger to the pain of loss, people assert their strength and potency—their refusal to succumb passively to the impositions of others. Blaming others is an aggressive act that focuses anger.

Psychological and cross-cultural studies of bereavement report affective and behavioral responses to death ranging from sadness to hostility (Marris 1974; Rosenblatt, Walsh, and Jackson 1976). Although the Bedouin poetic or ritualized discourse rarely carries bellicose threats or sentiments of anger, the expression of these themes in ordinary discourse suggests that Awlad ʿAli express the range of sentiments associated with bereavement and loss, but in a culturally specific, culturally regulated, and nonhaphazard way. LeVine (1982b) argues that individuals in particular cultures selectively interpret death in the idiom of the dominant themes of interpersonal relations. Huntington and Metcalf (1979, 43) argue that “cultural difference works on the universal human emotional material. . . . The range of acceptable emotions and the constellation of sentiments appropriate to the situations of death are tied up with the unique institutions and concepts of each society.” The Bedouin response provides support for these anthropological positions on the cultural construction of the sentiments associated with death, with one modification: different cultural forms may carry different sets of sentiments.

The same people who so energetically present themselves as invulnerable and assertive in loss situations, who dramatically disavow the experiences of helplessness, vulnerability, or passivity that would compromise their images of being strong and independent, portray themselves differently through their poems. In their poems and in the ritualized “crying” of mourning, they express sentiments of sadness and confess feelings of devastation: tears and ailments signal the impact of the losses; constant references to “despair” betray a sense of helplessness. In Awlad ʿAli terms, helpless passivity in the face of assaults is the mark of impotence, and vulnerability to the pain inflicted by loss suggests attachments that, in the language of honor, translate as dependency and weakness. The discourse of poetry and ritualized mourning is one of vulnerability, weakness, and dependency.

Why the Bedouins can express through poetry the sentiments of weakness that violate the code of honor, why listeners apply a different set of standards regarding conformity to the societal ideals to presentations in this medium, and what the significance of having two contradictory discourses is, are questions that will be taken up in the final chapter. To be able to consider them, however, another dimension of the use of ghinnāwas in social life must be explored. In the next chapter, I look at the relationship between poetry and love.