CHAPTER ONE

SUMMER 1864

Jubal Early was a day late.

Washington D.C. was laid out before him and his small army in the late-July sun. Early could even see the dome of the Capitol. It beckoned to him: attack!

But instead of lightly manned fortifications, the parapets around the city were, according to Early, “lined with troops.” The fort to his immediate front, known as Fort Stevens, was bustling with Yankees. His army—which had conducted long marches, a pitched battle two days previously at Monocacy, and then another forced march to Washington—was exhausted.

Prudently, Early called off the assault.

Although unable to capture or seriously threaten the city, Early did take some solace from the attempt. “Major, we haven’t taken Washington, but we scared Abe Lincoln like hell,” he remarked to an officer soon after leaving the outskirts.

President Abraham Lincoln and his general in chief, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, would soon draw up plans to make sure Early or any other Confederates would never scare “Abe Lincoln” and Washington again.

After the Union defeat at New Market in mid-May, Maj. Gen. David Hunter had taken over command of Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley. Hunter promptly moved up the Valley and threatened the vitally important railroad depot of Lynchburg.

This Federal presence forced Gen. Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, to act. Locked in a continuous struggle with Union armies around Richmond, Lee dispatched his most trusted subordinate, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early, to rescue the city. By railroad and by marching, Early and his Second Corps arrived in the nick of time and defeated the Yankees on June 17-18, 1864. The victory sent Hunter scurrying into the mountains and cleared the path for Early to march to the Potomac River.

THE AREA OF OPERATIONS FOR THE AUTUMN SHENANDOAH VALLEY CAMPAIGN OF 1864—Framed by the Allegheny Mountains to the west and the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east, with Massanutten Mountain running down part of its center, the Shenandoah Valley had seen significant action in the spring of 1862. It continued to bedevil the Federal government at the Confederates’ “back door of invasion.” Grant finally addressed the problem after the impotent Confederate run on Washington in late July of 1864.

The Shenandoah Valley not only offered some of the most scenic landscapes in Virginia, it also served a vital role as “the Breadbasket of the Confederacy.” (DD/PG)

At the head of “Stonewall” Jackson’s old command, Early did just that, taking the war from Lynchburg to the gates of Washington.

Understandably, with the presidential election looming in the fall, Lincoln could not let such an invasion happen, especially on the high-profile heels of previous Confederate incursions across the Potomac, which had each set off waves of fear and panic across the North. Coupled with the high casualty figures from Grant’s Overland campaign—the Federal effort to destroy Lee’s army that spring—popular support for the war in the North was beginning to wane. If Lincoln hoped to win reelection, the elimination of the Shenandoah Valley as an invasion route would have to be a top priority.

Known as the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy,” the lush Valley stretched from Lynchburg in the south to Winchester in the north, bracketed by the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and the Alleghany Mountains to the west. Running like a spine through the Valley is Massanutten Mountain. It begins east of Harrisonburg and continues for 71 miles until leveling off south of Middletown. This mountain dissects the larger valley into two smaller valleys: the Shenandoah and Luray.

In June, Maj. Gen. David Hunter was the latest in a string of Federal commanders to come to grief after operating in the Valley. (LOC)

The main thoroughfare through the Shenandoah Valley was the Valley Turnpike. Harrisonburg, Strasburg, New Market, and Middletown sat astride it. Railroad lines also ran into and through the region. The Shenandoah River, the main water source for the Valley, flowed from south to north. Thus, if an individual traveled north from Lynchburg to Winchester, they were going “down the Valley;” people heading south from Winchester were going “up.”

Because of its geography, the Valley made a perfect “back door” for invasion. In 1863, Lee had used the Valley as an avenue of advance, emerging from the mountain ranges in Pennsylvania. The campaign culminated in the battle of Gettysburg, which left more than 50,000 casualties. The extreme loss of life provided the backdrop for President Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.” The president hoped that these men “had not died in vain.”

Now, a year later, Early had reached the doorsteps of Washington using that same route. Only the delaying action at Monocacy, which would eventually become known as “The Battle that Saved Washington,” prevented Early’s Confederates from slipping into the city. This back door of invasion had to be closed.

Unfortunately, after the Southern legions marched away from Washington, the Union response was anything but decisive. One of the issues was the confusing problem of authority. The Federals had departmentalized different regions. Four military departments embracing Washington, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and the Shenandoah Valley needed to be merged into one. These departments had different commanders, and coordination in an orderly manner was difficult to achieve—and so, after threatening Washington, Early slipped back to the Valley unopposed.

After the failed pursuit of the Confederates, Grant had to appoint a new commander who would have authority over all the departments and be responsible for destroying Early’s army.

Under consideration were Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin; former commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan; and the current commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton balked at all three propositions.

McClellan’s name had been floated as a possible ploy to keep him from running against Lincoln for president in the fall. However, his contentious relationship with Lincoln and one-time political ally Stanton almost assured more of the same sorts of problems and delays that had led to McClellan’s removal from command a year and a half earlier. Nor could Lincoln afford the other edge of that sword—on the outside chance that McClellan performed well, it would only bolster Little Mac’s bid for the White House. The next candidate, Franklin, was passed over because of the lackluster record he’d amassed with the Army of the Potomac earlier in the war. Meade, too, was rejected; Lincoln was holding back political forces wishing to have the Army of the Potomac commander replaced, and the president did not want to appear as though he was appeasing the opposition.

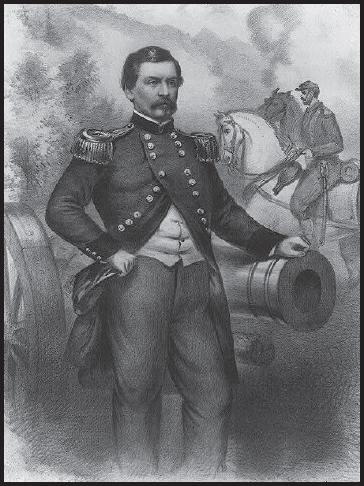

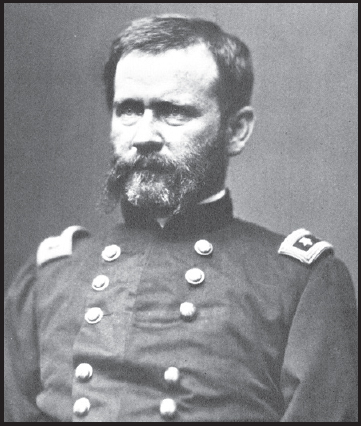

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the former commander of the Army of the Potomac (top), Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, its current commander (below), and Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin (bottom) were among those considered to command the new Union army in the Shenandoah. (LOC)

With his attention focused on the trench warfare around Petersburg, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant needed a subordinate with an aggressive spirit to spearhead operations in the Shenandoah Valley. (LOC)

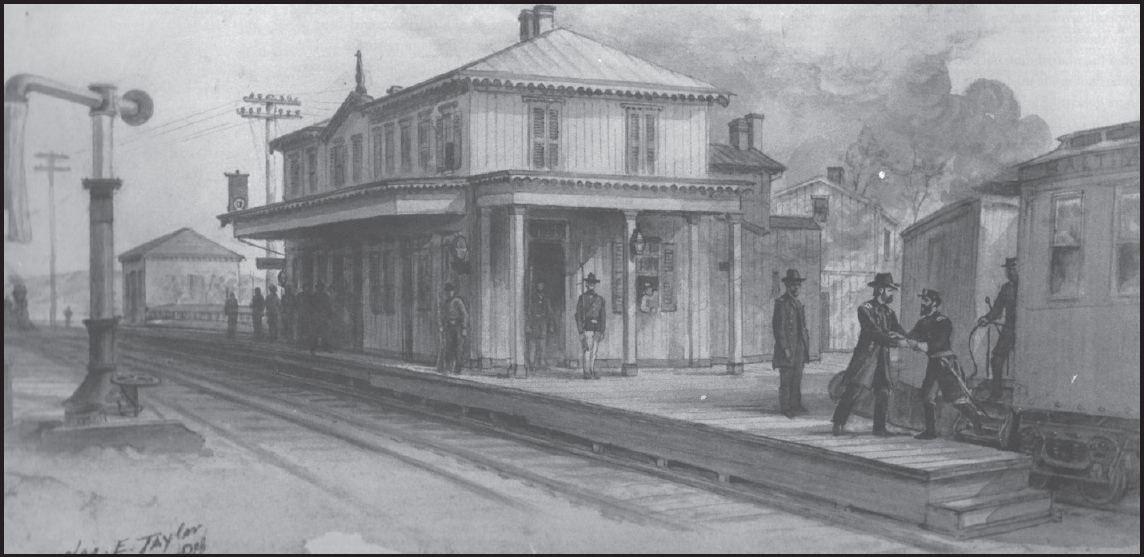

Finally, Grant proposed Meade’s chief of cavalry, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan. Lincoln and Stanton again had their reservations, but time was of the essence, and they acquiesced. On August 6, Grant and Sheridan met outside Frederick, Maryland, at Monocacy Station. There, Grant handed his subordinate written orders for the task ahead. The two men departed in opposite directions; time would tell if they were also starting on diverging destinies.

* * *

The campaign waged in the Shenandoah Valley that year would take on a greater significance than its sister campaign two years earlier. In the spring of 1862, Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas Stonewall Jackson used the geography of the Valley to influence Union strategy in Virginia. Jackson’s victories at Front Royal, Winchester, Cross Keys, and Port Republic managed to keep reinforcements from being sent to Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s Union army advancing on Richmond.

Grant and Sheridan met at the Monocacy rail station outside Frederick, Maryland. (WRHS)

In 1864, the outcome would have an impact on the entire Union war effort itself. With operations there taking place on the eve of the November elections, any adverse outcome in the Valley could influence the Northern populace as they went to the polls to cast their ballot for the next president of the United States. Although Atlanta had fallen in early September, improving Lincoln’s chances for reelection, Virginia still remained a focal point. With Grant and Meade bogged down in front of Richmond and Petersburg, all eyes were on the Valley. A major Union defeat there could counterbalance the gains achieved by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman in Georgia.

This could not have been comforting to Abraham Lincoln or the rest of the Union high command. The Shenandoah Valley was a place where Union hopes had been dashed in the past, and there was nothing to indicate that this time things would be different.

For the Southern cause, the Valley had been a scene of pride and victory. During the summer of 1864, Jubal Early had used the region to threaten Washington. If he could maintain a tight hold on the Shenandoah, the advantages to the South would be numerous. The Confederates could continue to threaten northward, force the detachment of additional Union troops to the region and thus weaken the grip on Richmond and Petersburg, and continue the production of materials and produce essential to the war effort. Stonewall Jackson’s words “If the Valley is lost so is Virginia” could not have been more prophetic two years later.

With a new cast of characters, the Valley would take center stage again in the fall of 1864. The rolling hills and flats between the Alleghenies and the Massanutten would play a crucial role in the coming drama. During this act, the region would witness something yet to be seen in that part of Virginia: the concept of total war. Consequences of defeat would be disastrous to either side. The outcome of the great struggle that had plagued the nation was on the line.

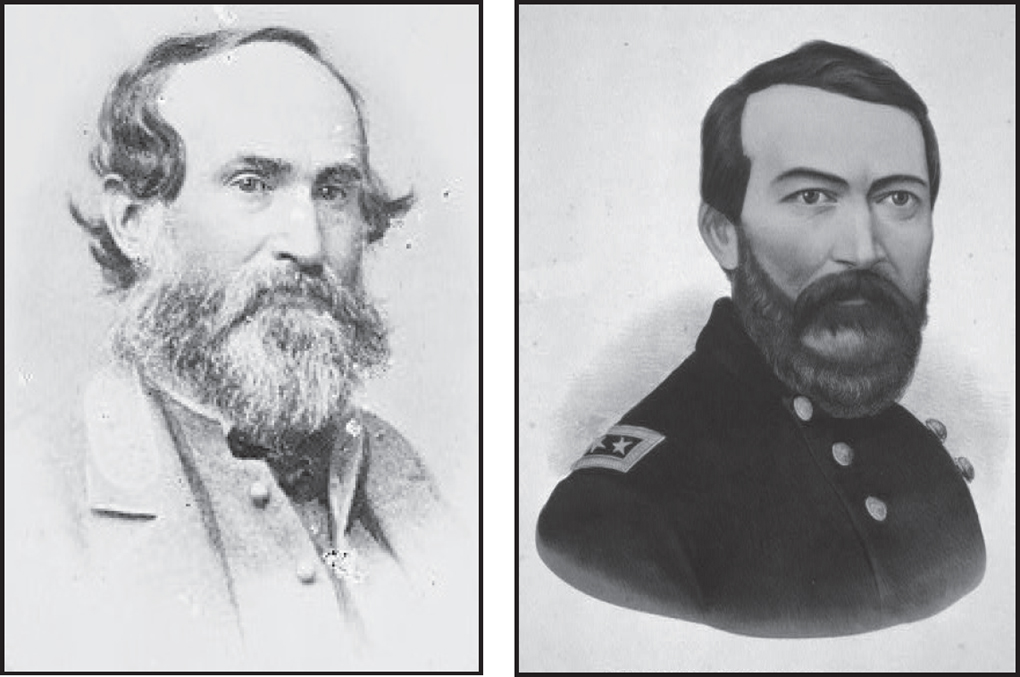

Lt. Gen. Jubal Early, C.S.A. (left) and Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, U.S.A. (right) led the Shenandoah armies that would clash throughout the bloody autumn. (LOC)

As Jubal Early studied Washington’s defenses outside Fort Stevens, President Lincoln stood inside the fort, studying Early’s Confederates. His stovepipe hat made him a noticeable target, and soon Lincoln came under fire—only the second time a sitting president had been fired upon during wartime (Madison, during the War of 1812, was the first). The site, now maintained by the NPS, is near Georgia Avenue at 13th Street and Quackenbos Street NW. (PG)