CHAPTER TWO

SUMMER 1864

Philip H. Sheridan was not physically impressive. Standing at 5’5”, many of his peers towered above him. President Lincoln, an astute observer with a flair for description, called him a “brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such arms that if his ankles itch he can scratch them without stooping.” Sheridan’s contemporaries also remembered his oddly shaped head. Perhaps to hide this feature, Sheridan more often than not wore his hat at an angle.

Yet inside this small frame, there burned a fiery ambition that was fueled by a hair-trigger temper and a strong will to succeed, no matter what the cost. “You will find him big enough for the purpose before we get through with him,” Grant once said of him.

Sheridan was 33 years old when he was selected to command the Army of the Shenandoah. It was for this reason, age, that President Lincoln and Secretary Stanton were hesitant to approve his appointment.

Their new army commander grew up in the hamlet of Somerset, Ohio, in the eastern part of the state. In 1848, he was appointed to West Point. Suspended for a year for an altercation with a fellow cadet, Sheridan finally graduated in the Class of 1853. His antebellum service was monotonous, and promotions were slow. By the fall of 1861, when he headed east to participate in the War of Rebellion, he had risen to the rank of captain.

Promoted to brigadier general in September 1862, “Little Phil” led an infantry division at Perryville, Stones River, and Chickamauga. For his actions at Stones River, Sheridan was promoted to major general. In November 1863, Sheridan led the assault on Missionary Ridge that broke the siege of Chattanooga. These actions did not go unnoticed by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. The following March, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and made general in chief of the Federal armies. Coming to Virginia to direct operations, Grant brought Little Phil with him and gave him command of the cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac.

This assignment did not fit well. Sheridan botched the opening maneuvers of the spring campaign when he failed to cover the army’s right flank—a failure that ultimately led to the two-day bloodbath in the Wilderness. After the battle, he failed to secure the army’s route to Spotsylvania Court House. This debacle completely soured his relationship with the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade.

Sheridan spearheaded the assault to take Missionary Ridge and break the Siege of Chattanooga in November 1863. (LOC)

On May 8, a meeting between the two quickly escalated into a fiery verbal confrontation. Surprisingly, this did not result in Sheridan’s censure. Instead, Grant sent Sheridan with his entire corps southward to engage the Confederate cavalry. Although Sheridan could count the May 11 battle of Yellow Tavern and the death of Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart as a victory, the day following the engagement, he was nearly surrounded and trapped outside Richmond. In June, Sheridan and two of his divisions were stopped by Stuart’s successor, Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton, during a raid on the Virginia Central Railroad at Trevilian Station.

The Trevilian Station battlefield, where Sheridan’s cavalry was turned back during a raid in June 1864. (DD)

In short, Virginia had not been kind to Phil Sheridan. His shortcomings were apparent. Any misgivings about his abilities on the part of other officers within the army may have been kept private so as not to offend the temperamental Sheridan or the proud general in chief Grant.

Grant probably also understood that, due to the catastrophe on the march to Spotsylvania, Sheridan could not work with Meade. It may not have been due to Sheridan’s past successes, then, but rather his recent failures, that Grant recommended him to command the Army of the Shenandoah.

When Sheridan assumed his new command, he had more than 40,000 men in all three branches to put in the field against Jubal Early. His men came from a range of states, including Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, West Virginia, and Iowa. The foundation of the army was the battle-tested VI Corps from the Army of the Potomac, led by Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright.

Wright relied on the combined experience of division commanders David A. Russell, George W. Getty, and James B. Ricketts—all of them brigadiers. Russell had begun the conflict as a colonel and rose through the ranks. Getty had held various posts during the early years of the war and was wounded at the Wilderness. Ricketts had been fighting for the Union cause since First Manassas. The backbone of the corps was a brigade from Getty’s division. Made up of six regiments from Vermont, these men were some of the best-disciplined and hardest fighting men the North had to offer.

Sheridan could also call upon the XIX Corps from the Army of the Gulf, commanded by Maj. Gen. William Emory. Like Wright, Emory also had two veteran division commanders, Brig. Gen. William Dwight and Brig. Gen. Cuvier Grover. Both had seen service in Virginia earlier in the war, and Dwight had been wounded at the battle of Williamsburg, in May 1862.

Upon arriving in the Valley, Sheridan also inherited the Army of West Virginia. As its name implied, this unit consisted mainly of men from the newly formed state. It was commanded by one of Sheridan’s roommates at West Point, Maj. Gen. George Crook. Colonels Isaac Duval and Joseph Thoburn led the divisions. Both were experienced fighters.

VI Corps commander Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright (LOC)

Twelve batteries of artillery supported the Army of the Shenandoah. Directing the guns attached to the Army of West Virginia was Capt. Henry DuPont. DuPont had graduated first in the West Point Class of May 1861 just after the war began. At New Market, DuPont had distinguished himself by using his batteries to cover the retreat of the Union army.

Three divisions of cavalry were assigned to the army, led by Bvt. Maj. Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert. Brigadier Generals William W. Averell, Wesley Merritt, and James Wilson commanded these divisions. Averell had fought at Hartwood Church, Kelly’s Ford, and Droop Mountain. Merritt’s solid service with the U.S. Regulars had earned him a general’s star on the eve of the battle of Gettysburg. Wilson, like his army commander, had come to the eastern army in the spring of 1864.

Although the VI Corps formed its nucleus, the army’s greatest asset was the cavalry. The role of the Union cavalry had changed drastically since the war began. By the autumn of 1864, these troopers had transitioned from scouts and escorts to a mounted strike force. The horse was no longer a means of transportation—it was a source of mobility used to move armed men from point to point. Many in the ranks were armed with the repeating seven-shot Spencer carbine and were augmented by batteries of horse artillery. These factors made Sheridan’s troopers more than capable of contending with their gray counterparts. It also put them on a superior plain when confronted by enemy infantry.

Sheridan (standing, center) surrounded by members of his staff: Henry Davies, Wes Merritt, James Wilson, Al Torbert and David Gregg (LOC)

That enemy army was commanded by the colorful “Old Jube.” Along with the moniker “My Bad Old Man,” Early had two of the most fitting nicknames given to any leader outside of “Stonewall” in the Confederate military. Both of his nicknames were well-deserved. He had a short temper, was not immune to using an array of swear words, and was a fearless combat leader. Part of his cantankerous temper can be traced to suffering from severe arthritis. General Robert E. Lee was credited with giving Early the second of his two monikers, “My Bad Old Man,” as Early was the only officer with the nerve to curse in the presence of the Southern leader. Lee purportedly overlooked Early’s profanity because the “Bad Old Man” fought so well.

The irascible Early was born on November 3, 1816, in Franklin County to a wealthy and well-connected Virginia family. He attended academies at both Danville and Lynchburg in preparation for his entry into West Point in 1833.

Early’s counterattack at Prospect Hill during the battle of Fredericksburg helped to stabilize the Confederate line during the battle. (DD/PG)

While attending the academy, an argument with future Confederate Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead escalated to the point that Early had a plate smashed over his head. Armistead resigned instead of facing the chance of dismissal. Early continued on, and upon graduation in 1837, he fought in the Seminole War before resigning in 1838.

After his resignation, Early studied law and began a practice in Rocky Mount, Virginia. He would return to the army in January 1847 as a major in command of Virginia volunteers during the Mexican-American War.

When Virginia seceded, Early entered Confederate service, receiving the rank of colonel of the 24th Virginia Infantry, which he led at the battle of First Manassas. He received his brigadier general commission shortly thereafter due to the role he and his regiment played in this first major battle.

Early was wounded at the battle of Williamsburg, but after his recuperation, he participated in every engagement of the Army of Northern Virginia. He earned promotion to the rank of major general in January 1863 and to lieutenant general in May 1864. When Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell was ordered to oversee the defenses of Richmond in May 1864, Early succeeded him as commander of the Second Corps.

By September 1864, Early’s Army of the Valley numbered approximately 13,000 men. The infantry and artillery accounted for 9,000 while the cavalry comprised the rest. Confederate veteran G. H. Baskett gave the following description of a typical Confederate soldier:

A face browned by exposure and heavily bearded … begrimed with dust and sweat, marked here and there with the darker stains of powder … a frame tough and sinewy, and trained by hardship to surprising powers of endurance. Above this an old wool hat, worn, and weather beaten … over a soiled shirt, which is unbuttoned and buttonless at the collar, is a ragged gray jacket that does not reach the hips, with sleeves inches too short. Below this trousers of a non-descript color, without form and almost void, are held in place by a leather belt to which is attached the cartridge box … and the bayonet scabbard … dirty socks-disappear in a pair of badly used and curiously contorted shoes.

For a large number of the Virginians in Early’s command, the return to the Shenandoah Valley was a homecoming. Most had fought in the Valley campaign of 1862. More than half of the Virginia regiments were recruited entirely or in part from the Valley region. These men could be counted on to go above and beyond because they were truly defending “home and hearth.”

The soldiers had trust in Old Jube. An artillerist pronounced Early as “without a superior in the Army of Northern Virginia” on the eve of the campaign. A Georgia private probably spoke for countless others when he wrote, “Expect a glorious victory for us—the ‘Old Guard.’ God be with the right.”

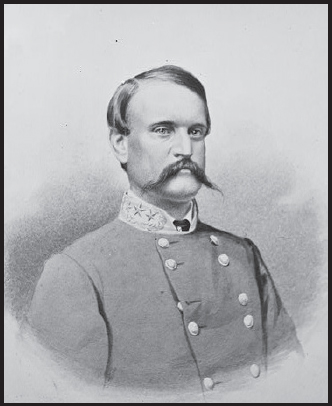

Maj. Gen. John C. Breckenridge (LOC)

Leading the “Old Guard” were some of the best commanders in the Confederate service. Major General John C. Breckinridge, a former vice president of the United States, commanded one corps. His divisions were headed by Maj. Gen. John Gordon and Brig. Gen. Gabriel C. Wharton. Wharton had escaped from Fort Donelson in February 1862 and had seen extensive service in the Valley and western Virginia. One of the notable brigades in Wharton’s division was commanded by Col. George S. Patton, grandfather of Gen. George S. Patton of World War II fame.

Gordon was the only division commander in the Army of the Valley who had not attended a military college prior to the war. Besides a brigade of Georgians, his division consisted of the consolidated remnants of the old “Stonewall Brigade” and “Louisiana Tigers.” To balance his force after Lynchburg, Early had temporarily assigned Gordon’s division to Breckinridge’s command. Later, in the middle of September, Breckinridge would be transferred to organize Confederate forces in southwestern Virginia and Gordon would return to the Second Corps.

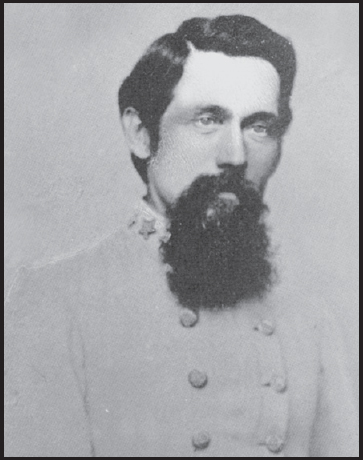

Maj. Gen. John Brown Gordon (LOC)

Along with Gordon, Early could rely on two other experienced division commanders in the Second Corps, Maj. Gens. Robert E. Rodes and Stephen D. Ramseur. The former was promoted to the rank after Chancellorsville and performed well at Spotsylvania Court House. Coincidentally, Ramseur had been wounded at both battles.

The artillery supporting the army consisted of five battalions and was commanded initially by Brig. Gen. Armistead L. Long. Attached to the army were 4,500 to 5,000 cavalry commanded by Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee. A nephew of Gen. Robert E. Lee, Fitz was a protégé of the late Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart.

Brig. Gen. Gabriel C. Wharton (LOC)

On these men, Early would lean in the hopes of recapturing past glory.

Harper’s Ferry National Historical Park maintains the 1860s charm of the village. Located at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers and home to a prewar arsenal, Harper’s Ferry proved strategically important but tactically impossible to hold. As a result, it changed hands multiple times during the war. (CM)