CHAPTER NINE

OCTOBER 10-18, 1864

The resounding victory of October 9, 1864, was further proof to Phil Sheridan that the Rebels were finished. In his mind, he had whipped the Confederates at Third Winchester and Fisher’s Hill. Now, he had soundly defeated the cavalry at Tom’s Brook. Taken together with the thorough dismantling and destruction of the agricultural infrastructure, Sheridan believed that the campaign was effectively over—an opinion he’d come to back when his army encamped around Harrisonburg some two weeks ago. Two days after Tom’s Brook, he had written to Grant of his thorough “cleaning out of the stock, forage, wheat, provisions, etc. in the Valley.”

That is why, as he marched north from Strasburg on October 10, Sheridan ordered the VI Corps toward Front Royal while the rest of the army went into camp along Cedar Creek, just south of Middletown. It was Little Phil’s intention that the VI Corps return to the front at Richmond and Petersburg.

When this intelligence reached Early, the Confederate commander moved to counteract this possibility. Lee’s army, ensconced around Richmond and Petersburg, already faced overwhelming numbers. The return of the VI Corps would only add to the disparity. Early had figured out “what [Sheridan] intends doing” and laid out to Lee the options he had before him.

Early didn’t wait for a response, though, and on October 12, the Confederate army began its march down the Valley.

“This is a time of great trial,” wrote Maj. Gen. Stephen Ramseur to a family member, assuring the relative “we are all called on to show that we are made of the true metal.” Early would put that “true metal” to the test shortly.

The Hupp’s Hill Civil War Park offers a museum with exhibits that encompass the actions in the Valley in 1864 (above). Visitors can explore the property through walking trails that follow Civil War entrenchments (bellow). (CM)

Most of the army went into camp around Woodstock on the night of October 12. By the next day, Early’s army had approached the vicinity of Fisher’s Hill, the scene of their reversal the previous month. The next morning, October 13, the Army of the Valley suddenly appeared at Hupp’s Hill, just south of Cedar Creek. Confederate artillery soon maneuvered into place, and the artillerists went through the procedures of ramming in a welcome message to their Union counterparts. The first shells arched through the sky and into the camp of the XIX Corps, scattering the blue-coated soldiers in every direction. In response, the Yankees sent the brigades of Col. George Wells and Col. Thomas Harris across the stream to investigate.

During the ensuing fight, the two sides slugged away at each other. Finally, the Confederates brought up reinforcements and managed to drive the Yankees back to their encampment.

Both sides had little to show for the skirmish, save for the loss of two brigade commanders. The wound sustained by Confederate Col. James Connor resulted in the amputation of a leg. Union Col. George D. Wells did not fare as well. He died from a chest wound. Ultimately, Early withdrew back to his old position at Fisher’s Hill.

The skirmish was enough for Sheridan to countermarch the VI Corps to Middletown. Still, the Federal commander felt that the campaign and the part his army had played were over. Unfortunately for Sheridan, Grant did not agree. He continued to prod Sheridan to commence operations against the Virginia Central and Orange and Alexandria railroads in central Virginia. A three-day cavalry expedition did little to satisfy the commanding general.

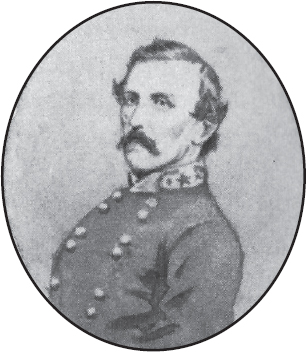

Brig. Gen. James Conner was wounded at Hupp’s Hill. (WRHS)

* * *

The day after Hupp’s Hill, Sheridan received a telegram from Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. The secretary wanted to weigh in on the matter of future operations and wanted to speak to Sheridan first before consulting the general in chief. On the night of October 15, Sheridan began the trip to Washington, leaving his army in the hands of Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright. When Sheridan consented to a meeting in Washington with the top brass of the Union war effort, he was content that Confederates posed no offensive threat to his army.

The Confederates, however, declined to be quite so accommodating.

As if he needed any urging from Lee, Early was putting the initial plans in motion for an attack. He set on a flanking movement as the most likely to succeed. Lee believed that if Early could use his entire army “it [victory] can be accomplished.” That was all the direction the ever-aggressive Early needed to advance his plans.

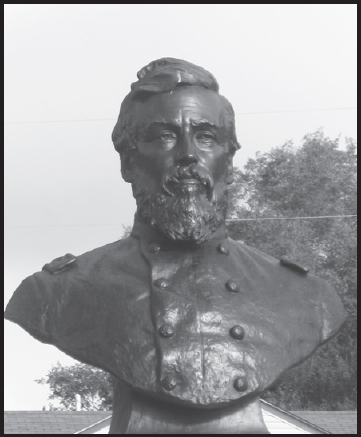

Col. George D. Wells, brevetted brigadier general, was mortally wounded during the action at Hupp’s Hill on October 13,1864. His bust sits atop a monument in the Winchester National Cemetery. (DD/PG)

On October 17, Early directed Maj. Gen. John Gordon; Brig. Gen. Clement Evans, who commanded a brigade under Gordon; and Jedediah Hotchkiss, the army’s topographical engineer, to conduct a thorough examination of Sheridan’s lines. Suffering from arthritis, Early was unable to scale the steep summit of Massanutten Mountain, known as the “Three Sisters.”

The village of Middletown. Sheridan’s army encamped in the surrounding area after the battle of Tom’s Brook. (WRHS)

Gordon and Hotchkiss undertook a reconnaissance mission atop Massanutten Mountain to scope out Federal positions. (WRHS)

Ever one for drama, Gordon wrote later that their view of the Union lines “was an inspiring panorama.” What was visible to Gordon was “not only the general outlines of Sheridan’s breastworks, but every parapet where his heavy guns were mounted, and every piece of artillery.” Furthermore, Gordon boasted that he could see “distinctly the three colors of trimmings on the jackets respectively of infantry, artillery, and cavalry, and locate each, while the number of flags gave a basis for estimating approximately the forces we were to contend with.” This opportunity, reminisced Gordon, “required … no transcendent military genius to decide” on the course of action the Confederates could take.

A view of Massanutten Mountain from the rear of the Union lines at Cedar Creek (DD/PG)

Hotchkiss went to work doing what he did best, making a map of the Union positions and the topography. As the trio returned that night, they hammered out a plan, and Hotchkiss left to report the findings to Early.

* * *

The next day, Early was approached by another of his division commanders, Brig. Gen. John Pegram, who had devised a plan of his own. Hotchkiss was present when Pegram outlined his thoughts, and the cartographer proceeded to report what his party had perceived and strategized the night before. Early was noncommittal and sent out a request to his subordinates to report to headquarters and discuss future operations.

The four other infantry division commanders—Gordon, Ramseur, Kershaw, and Wharton—joined Pegram in answer to Early’s summons. Also in attendance were Thomas Rosser and artillery chief Col. Thomas Carter.

The meeting convened around 2 p.m. Gordon did most of the talking. The plan he and Hotchkiss outlined was a flanking movement by the Second Corps around the Union left. This maneuver would be followed by a determined frontal assault by the rest of the army.

A question arose concerning the viability of marching an entire corps across the north face of Massanutten Mountain and across the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, which flowed along the base of the prominence. Gordon, who was as persistent as they came when he had his mind made up, insisted that a route could be found and that the enemy would believe the feat impracticable, thus ensuring the chance of a surprise assault. In the end, Gordon swayed the officers present, including Early, by stating he would accept full responsibility if the plan backfired. He would take 6,200 men of the Second Corps on a sweeping flank attack around the Union left—exactly the kind of maneuver these former men of Stonewall Jackson’s were accustomed to.

The Georgian’s plan won out and orders were issued to the different commands. Working in concert with the Second Corps’ assignment, Kershaw’s division would head to Bowman’s Ford along Cedar Creek and cross there. Wharton and the artillery would be guided by the Valley Pike to Hupp’s Hill; when he saw or heard that Gordon and Kershaw engaged, he was to pass down the Valley Pike and push to Middletown. Rosser’s cavalry would cross Cedar Creek at Cupp’s Mill Ford and initiate the engagement by taking on their Union counterparts. Other cavalry under Col. William Payne, who was also present at the headquarters meeting, would lead Gordon’s advance, surprising any Union pickets along the way before making a dash toward Belle Grove, an impressive country home that was known to be the headquarters of Sheridan. Gordon’s plan had Payne’s Confederate cavalry making an attempt at capturing the Union commander.

All units were ordered to be in position by 5:00 a.m. In the words of Evans, who had been part of the triumvirate that ascended Massanutten Mountain on October 17, the chance presented to the Confederates held the possibility to “utterly rout them.” That was the dream of Early and Gordon.