The last thing my mother sent me was a picture she’d taken of a cuneiform tablet in a small museum in Anatolia. At the top, a loinclothed king or god in profile, perspectiveless, the sun and moon above, and below, columns of tiny scratchings, letters, language leaping from stone. The image was badly lit. She must have stood to the side to move the glare from an overhead bulb to the margin of the tablet. I can picture her looking into the window of her phone, taking a side step, tapping the screen. She wrote, “The work’s going well, though your father still seems to think the problems in refugee camps owe to a lack of decorum and matching eating utensils. We’re sightseeing for two days. Tomorrow off to those big old slabs,” meaning the stelae at Göbekli Tepe, site of the world’s first religious temple, which they never did see. How bluely ironic that this last dashed-off email should have attached to it an image of a language grown from pictorial symbols carved on a hard slab of reality very like the headstones that serve now as their alter-presences. And cuneiform, so beautiful. From drawings in sand to sandstone to granite, Hittite and Sumerian to Semitic symbols to Greek, ox/house/camel/door became aleph, beth, gimel, daleth became alpha, beta, gamma, delta, the signs moving back and forth from yard to shelter, nature to artifice, country to settlement. In their origin alphabetical letters had the breadth to mark both the wild and the cultivated.

The NGO called me in Montreal, first with the news, then with the arrangements. I flew to Halifax to meet the so-called mortal remains, held steady through a small service, and saw them into the ground. When I looked up, suddenly orphaned, I decided to take to the skies.

In time I was living with a petite Londoner in a one-bedroom apartment in La Latina, a neighbourhood in Madrid. We sampled the city cheaply, hitting the discount hours in museums and bars, attaching ourselves to English groups on architecture tours, attending street protests, chanting in bad Spanish. On TV, soap operas confused us and soccer billionaires scored goals and then tore off in some direction as if chased by guard dogs. She worked as a copy editor for a travel magazine. For a few weeks she indulged me in language games, with imposed restrictions. No definite articles over dinner (“Please pass a pepper grinder.”), only one adjective for the weekend (“Then how would you describe me?” I asked. “You are insufficiently friended.”). No one-word utterances. Responding to any question of five words with a rhyme (“Do you like this dress?” “…The hemline’s low. I’d prefer less.”). I reasoned that the games marked us as distinct, kept us quick. Then the challenge of them became limiting, like badly fitted clothes, binding the limbs in mismeasured forms. For a time it seemed we’d never free ourselves, that we’d go mad together. We stopped having sex. And so we called off the games. It took a while to break ourselves of the habit of listening a certain way, for lapses or possibilities. We went silent, hours at a time, and, on the other side of silence, broke up.

Or that isn’t what happened. What happened was she realized she could no longer watch me sit motionless. To her I seemed to move at a great speed while reading or staring out the window at the crowds in the El Rastro flea market. She said, “You sit still the way other people run for their lives.” She thought I’d turned sitting into an act of cowardice, a way of avoiding hard truths. One day the truth was that she had fallen for her Spanish teacher and was moving in with him.

Alone, I cut all expenses. I quit smoking, lived on pasta and butter, but in the end my means ran down. As I left for good with my duffle bag, my landlord, a sad-eyed Italian Spaniard, held open the door and clasped me on the deltoid. “You are real. Real poets do not pay rent.” He’d seen me reading poetry and assumed I wrote the stuff. In truth I am only a failed poet. A failed many things. Bartender, textbook editor, doctoral student, orchestra publicist. I have no talents but reading.

I landed back in Montreal, living in a former professor’s basement. He was the closest thing to family I had left. A memory disorder had forced him into early retirement. Now his old students took turns going with him to medical appointments and grocery stores, looking after him in exchange for a basement room. Most hours of the day he was himself, lucid, funny, the Dominic Easley we all knew. But there were slips and lapses, especially in the evening, after wine. One night as we walked through the residential streets he tried to introduce me to his neighbour, a large woman out inspecting her garden. The neighbour and I understood even before Dominic that he’d lost my name, and as I said who I was, it was he who listened with the greater interest. That night in the basement I had never felt so unknown, even to myself. The feeling wasn’t loneliness but rather two emotions held together, one sadness, a simple word that simply applied, and the other something borrowed from Dominic, a distilled sense of being, of possibility, as if I had entered a state of perpetual, dreadful expectation.

Contained in that dim basement I felt something in approach. Then, out of nowhere, a stranger named August Durant sent me an e-ticket to Rome and an offer of six hundred USD a week to stay with him and conduct what he called “literary-detective work.” He stressed that he wasn’t hiring me as a sexual companion. I would put my one talent in service of solving “a mystery of dimensions unknown” even to him. I was without other prospects. Either I found paid work or I’d become accommodated to the sorry view of myself as destined for still more years of drift and small failures, trying to stay out in front of hard truths. But a detective. Hack gumshoe or houndstooth or hard-boiled? Would I be figuratively armed? Would there be a good story? Would its end be mine?

Words grow out of the world and then back into it, made of the very history they string together. An enduring one comes out of the Old English morðor, the Old Norse morð, and several related variants, meeting the line from the medieval Latin murdrum and the Anglo-French murdre. The word is there very near the origin of stories, right after first light, and now it’s all through every story, even when it doesn’t seem to belong and we imagine we don’t see it.

Durant knew me as the author of an online rant I’d gone so far as to give a title: “The Poet at the End of the World.” There had appeared on the internet a new poetry site called Three Sheets. The anonymous host posted only his or her own poems, most short, some untitled, and yet amid all the traffic noise, the page drew a surprising aggregate of readers, for a poetry site. At first these readers were other poets and academics, who within six weeks built two new sites devoted entirely to the verse of the mystery poet who for a time was called the New Anonymous, or Nanny for short, and to the enigma of his or her identity. Theories sprung up around the names and cities and historical events alluded to in the poems. Something calling itself the Group Against Three Sheets (GRATS) arose to attack Nanny for “a mockery of the provocateur spirit” and to pronounce Three Sheets “insufficiently political in its conception.” Another, the Group Against the Group Against Three Sheets (GRAGRATS), the name and acronym chosen, as its founding manifesto stated, precisely for their absurdity, considered the anonymity central to what came to be called the Project, and defended the poet’s choice to remain unnamed, and even insisted that there be no provisional designations, and so asked that people stop using “Nanny” to mean “the anonymous one” (uncapitalized), a corrective that somehow became widely adopted. (GRAGRATS) chose the symbol @ to designate the poet. The rest of us just called him or her the Poet.

One morning in the Montreal basement I’d taken a stroll past the Sheets-inspired sites, read the latest skirmishes, which usually amused me unintentionally, and came away wanting to throw stones at both sides. In any country, debates among poets are comically vicious, the stakes being so low. Though I’d intended never to add my voice to the babble, I couldn’t stop from saying what no one else would say and posting it on the Sheets Project Meta-Site of Record (SHEPMETSOR). Roughly reduced, my point was that the debates over Three Sheets were being conducted almost entirely by people with no feeling whatsoever for poetry, mostly academics and bad poets, and were these people capable of reading better, they’d see that the Poet was addressing an audience in the habit of filtering out bleatings such as theirs, and that, in fact, the most coherent theme or subtext discernible in the Poet’s work suggested not a communal, consensual, or debatable set of ideas, but rather a soul’s draw toward a single, fixed mystery.

“The mystery itself is unnamed. Is it a lost loved one? a lost god? All we find is an absence. Absence is the most present thing in the poems.” I’d fallen into a conviction and was more or less stabbing the keys. “Most of you are failing the Poet and the poems. As readers, you are thin where you should be thick, and otherwise thick through and through.”

That last line now embarrasses me. I don’t sound like myself, even myself in prose. Dominic chose not to call me on the brattiness of the tone, or the generalization I’d made about academics, though he was a better and more soulful reader than I. He read Durant’s letter of invitation, looked in on Three Sheets, and pointed out that I was entertaining a solicitation from someone unstable or at least very likely in one of the categories of thin readers that I’d attacked.

“If you need the money, though, you can always tell yourself that this Durant must concur with your reading of the Poet, and so taking his money might not be ignoble. And anyway, it’s not just money, it’s Rome!”

It was more than Rome, in the end, but in Rome it began.

The next week I handed over my room and caretaking duties to a former classmate and flew off, anticipating disaster. Dominic had gifted me a few nights in a budget residenza in Trastevere. I had been to Rome once before, with no money, and seen the sights, sipped the coffee at Tazza d’Oro, felt the black cobblestones in the soles of my feet, in my throat, under my eyelids when the last stranger home turned out the light in the room for males in a hostel near Termini Station. I’d been alone then, in my early twenties, and now eight years later was alone again. Being always in silence had left me without a means for any human gesture toward comprehension, and the traffic and murmuring tourists only sharpened for me the silence of the buildings and stones, and cast me, in some faux-Romantic sense, with the dead.

In my small room I consulted my laptop to see what was happening at Three Sheets. There had been no new posts in a week, an unusual but not unprecedented quiet. When the site went still for a time I imagined the Poet entirely unplugged, reading old books, then wandering on a farm or in village streets somewhere temperate. He/she lived in a moderate climate, I deduced, but came from an extreme one, which was why the “runt days” with their “uncentered bubble of light”—winter days, surely—seemed to her/him “a native, wet element.” Only a nonnative would feel a damp cold as “native.” Of course the Poet might have been imagining the damp, or remembering a place where she (let’s say) no longer lived, but the description had appeared in February, with a topical reference to fires then ravaging Australia (“an outback town in cinders”).

Durant’s email notes had been short, not unfriendly but neither giving anything away. Before accepting his offer I’d found him on a faculty page at a private school in California I’d never heard of, Larunda College. The page had no photo and only a brief professional biography. August Durant had studied genetics at Berkeley and the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, and had taught at the University of Michigan for twelve years before moving to Larunda, where, it seemed, he taught very little. He was affiliated with universities in France, Holland, and England. The linked CV gave me a sense of his age—judging from when he finished his graduate work, he’d now be in his early sixties—and listed dozens of publications, the titles of which meant nothing to me except one on the American poets Wallace Stevens and John Ashbery. It was odd that he’d written an academic paper on poetry, and odder still that he’d listed it among all the articles on evolutionary biology and DNA transference on his CV, where it would mean nothing to his professional standing. He must have been proud.

The CV hadn’t been updated in three years. What had he been doing recently? I used Dominic’s access to online academic searches to learn that Durant had coauthored a successful and sizeable research grant on something called “molluscan phylogeny” (I couldn’t remember what phylogeny meant and could have sworn there was a k at the end of mollusc). He’d published a single paper, back in the first months of the grant, but nothing since. A distracted program assistant at the biosciences department told me that Durant was on leave. I said I was considering an application to Larunda, and she offered that Durant’s leave was “indefinite.” He was not available to supervise research. “Is he retired?” I asked. “You can think of him that way,” she said.

Apart from his professional life, there was scant evidence to read of him. Surely he knew even less about me, yet he seemed to have great confidence that I was his man, whether or not I knew it. “You can ask me whatever you like,” he wrote. “The plane ticket would have proven to most that I’m serious. All it really proves is that I have enough money to play my hunch, and anyway, even once you realize I’m serious, you still have to decide if I’m someone you can work for.” He was right, but now that I’d used the ticket, my concern wasn’t that he’d deceived me but that he’d learn I was a less talented reader-detective than he’d imagined. There’s a degree of cowardice or fraudulence in every reader who feels the need, upon closing a book, to open his mouth.

I cleared my throat and dialled his number. The voice that answered, in English, was certainly his—I could tell somehow by the vigorous, uninterrogative “hello.” As we spoke I could picture him, strong, sharp-eyed, square. He sounded like John Huston in Chinatown. The call was brief. We arranged to meet the next afternoon on a patio bar on Piazza Campo de’ Fiori. The presumption that had led him to send me the ticket was there now too, even in his attempt to reassure me.

“Anyone my age and with my way of seeing the world is bound to be a little complicated. You’ll need confidence for this work, James. I like boldness. So tomorrow check out of your hotel and bring your bags with you. You’ll know right away you can trust me, and you’ll like me, if that matters to you, which it does. Then we’ll begin our work.”

After the call I allowed myself to admit further doubts. Not just that my talents were less than he imagined but that the enterprise was absurd. I looked up absurd on my phone. It’s from the Latin absurdus, meaning “dissonant” or “out of tune.” Couldn’t Durant hear the notes? Because he presumed to know me well from a letter I’d posted online, I decided that his judgment was suspect. He was a truster of appearances. No one is transparent, though they may evidently be mostly joyful or not, mostly good or not, and so on. There’s always more to the story. To allow myself one generalization, people who express presumed certainties to strangers are often, at some level, fools.

My doubts made me miss the Londoner, so full of purpose, clear of mind. She’d studied mathematics and told wild tales about string theory to rewrap with fine gold any loose thought I’d strung with poetical catgut. Upon learning from her that forty is the only semiperfect number in English whose letters fall alphabetically, I thought I might say it to myself in times of confusion as a sort of mantric assertion of linear clarity. But then I started seeing it everywhere—it leapt from screen texts and formed in the fragments of sound broken off from the noise of the day—so that “forty” represented for me everything from the number of horses in the last five Grand National races to the percentage of my country’s commissioned soldiers listed as casualties in the First World War to the number of light-years from Earth to the planet 55 Cancri e to the number of days and nights of rain it takes to float an ark. I retain facts pointlessly—the Londoner thought I was “on the spectrum,” I told her the internet was to blame—but now and then, as if of their own accord, the facts try to arrange themselves into meaning. These little flights of free association, these high-lateral cha-chas, as I thought of them, came unbidden like a kind of seizure, and I had no choice but to wait them out. The more duress I felt, the longer they lasted. Maybe they cleansed the carbon buildup in the brain’s exhaust system, but they contained unlikely, surprising linkings, and in their wake I experienced a sudden clarity that could last for several minutes. The clarity didn’t always feel good.

Except for a few flower stalls, the market at Campo de’ Fiori had closed for the day by the time I arrived. The rich light on the buildings was as I remembered it. Durant had told me to look for the most crowded patio at the northwest corner of the piazza, the one the tour books listed. He’d be sitting in the otherwise identical neighbouring patio, likely the sole occupant, and that was, in fact, how I found him. He spotted me first or at least was looking right at me as I approached and picked him out, a man even larger than I’d imagined, standing to greet me, with full, light-brown, combed hair—I wondered if he was one of those late-middle-aged men who are proud of their hair—wearing black plastic old-style glasses over blue-grey eyes. Striking eyes, wolfen. He would know their effect. His clothes were casual, coarse cotton. He was smiling.

“You knew me by the duffle bag,” I said, shaking his considerable hand. We sat.

“And you don’t look Italian, or walk Italian. There’s also a picture of you on the internet. You must know the one.” It was a group photo. The Londoner and I met the other six when we were detained together by Parisian police as part of a mass roundup of climate change protesters at a meeting of big oil executives. We decided to gather again in Amsterdam a month later to join an alternative energy march. That’s where the picture had been taken, before we really got to know each other, which is to say, before the Londoner and I split from the others and moved to Madrid. I never thought anymore of those temporary friends, except the Londoner. I’d chatted with her briefly one Paris afternoon and in all of ten minutes she made a marching activist of me.

Through our first shared drink the conversation with Durant had no shape. I learned in passing that the room I’d have in his nearby apartment had a great street view, that he’d been in Rome for nine weeks and planned to stay several more, that his feet were suffering from a new pair of shoes, that he hoped, when his time in the city was over, never to hear another underpowered motorcycle. I nursed a beer, he a glass of Madeira. There was something more to these preliminary exchanges than simply to put each other at ease. It was understood that we were each gauging the other, each allowing time to find what would serve as an acceptable, reproducible version of ourselves that we could then play at length. I was fully aware that, against my will, I was constructing a persona—one that would not disappoint Durant, that seemed up to the job he’d offered me, but that too seemed authentic for being slightly peculiarized, as in my unwillingness to fill all silences with speech or ask the obvious questions—and that he must have been doing the same, though I couldn’t detect anything in him but a genuine interest in me, in my carry bag, which I’d picked up in Madrid from a Moroccan, and in the city around us. That I couldn’t detect a forced interest meant that he was older and more practised at the art of false presentation, or that he was less self-aware than I hoped, and didn’t know that we are only being true to human nature to fashion outward selves far removed from whoever we are when alone in the dark.

All this travelling I’d done—Paris, Amsterdam, Madrid—what had I learned about myself, he asked. I said I was neither searching for nor escaping anything. I just wanted to know what places were like, at least while I was standing in them. I didn’t say, as I might have, that I’d been unlocated since my parents died in a car accident.

“Your posting argues that the poems at Three Sheets are all directed toward a single, fixed mystery. It suggests you see beauty in the idea of a search. You’re looking for a direction. I have one for you.”

What had I written about a search? My little online piece had tumbled off the top of my head. I’d tangled myself up in Dante, the canto about Ulysses’s last voyage from The Inferno. The old sailor gathers his men and sets off for “the world beyond the sun,” meaning the west, where the sun sets, the unknowable distant point where things end, the day, the light, life itself. Was this the direction Durant had planned for me?

“Why bring me here? Why couldn’t I work for you from Canada?”

“Because the best discoveries are sometimes made when we’re not working, when we’re relaxing, talking about life and love, and I’m paying you for those conversations, too.”

We looked out at the passersby, the rooftop gardens on the buildings across the piazza. Several young Romans sat on the base of the statue of Giordano Bruno. Harmless teenagers, smoking, playing cool, feigning boredom. The light was clean. Durant waited me out. I finally asked him how he became interested in Three Sheets and the Poet.

“I discovered the site in a sidebar. I forget what I was reading online, likely something about Wallace Stevens or Elizabeth Bishop, and a fragment of poetry popped up and caught my eye. And so I looked at the site and the more I read, the more the work got hold of me.”

“The site’s gotten hold of a whole lot of people. Does it bother you that you might be part of a virtual cult?” My ground had been marked out by the online post, but now I stood on it, chin raised. I already knew that Durant liked this image of me.

“Let’s face it, the Poet’s work is at best uneven and pretty elusive. Half of it doesn’t even make sense. My relation to him—he’s a man, let’s agree—is more personal.” He measured my expression, which I tried to keep neutral. “I know how that sounds.”

He said that I could lay claim to “the sharpest post” on SHEPMETSOR. And I had no institutional affiliations that might skew my readings, no publishers to protect, no tenure to win. As far as he could tell from his internet searches, I was a perfect co-reader, and he needed a reader. He said not his life but “the makings” of his life were, as it were, “at stake.” I wondered if he’d introduced “the sharpest post” and “stake” intentionally.

“The Poet’s work has started to feel directed at me. Either I’m lost to delusion, and you might be able to help free me of it, or there really is a connection, and you can confirm that what I’m seeing in the poems is valid.” He took me in unblinking as he spoke, never once looked away. “Of course, you wonder what I’m seeing. And of course I can’t tell you or I’ll have planted the reading in your mind. I can only ask you to tell me what you see, though even this is an interference.”

If he wanted me as a measuring instrument, then already the needle was in the red. Superstitious readers project more meanings onto pages than they find in them. It is possible to see anything in language if you look with a particular slant and intensity like the one he was now levelling at me. Whole interpretive fiefdoms are built upon professors seeing gods in their porridge.

He looked off to the square. A young, hairy-legged couple in shorts had bolted from the neighbouring patio and run out to flag down a dark-skinned man in a blue summer suit. There was surprise and delight all around.

Durant’s hand fell off his glass, as if to make a gesture, but he changed his mind and simply took hold of it again.

“You must have some questions for me,” I said.

“No. But I do ask something of you. If you’re still considering this job.” Before I realized the question had been sprung, I answered, “I am.” Why I said this I still don’t know. If anything, I was inclined at that point not to become involved in the man’s suspect enthusiasms. Maybe I was just intrigued. Or maybe I didn’t want to walk away from the money.

He said that he’d pay my first installment regardless but wouldn’t hire me until he’d seen me read. He meant this literally. He needed to physically see me read a poem and then listen to my response, without aid of commentaries or search engines, and without the time to revise.

“You mean right now?”

“Yes.”

In Dominic’s Contemporary World Poetry graduate course, he’d made the class perform spot readings and then graded our discussions. Among students and his colleagues he was quietly denounced for the practice, but it was in those sessions that I learned to focus, to find meaning and test it, to find a way of seeing and a language for saying what I saw. But sometimes I saw badly, or not at all.

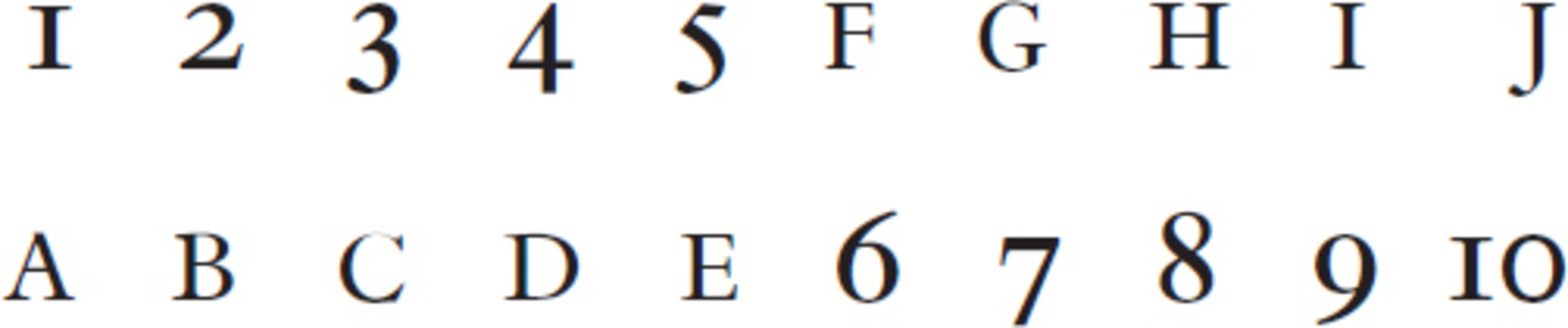

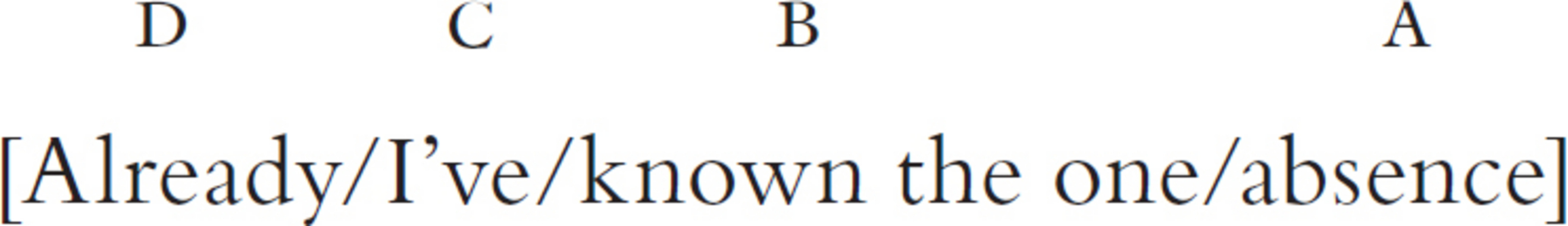

Durant produced a paper from his pants pocket and unfolded it, passed it to me. I recognized the poem, “The Art of Memory.” It had appeared in the late winter on Three Sheets. It hadn’t made much sense to me at the time, and it wasn’t my kind of poem, but I performed the trick I’d learned of faking to myself a silent enthusiasm, which sometimes triggered an actual one, which made me read better. What did I see? A simple rhyme scheme. The speaker addressing an absent lover, a woman who maybe knows something of the sciences (“The world, its laws slipped / into you like light through a lens to a point / of resolve”). He remembers them standing with a guidebook in the shadow of a bronze statue, and she says, “The sun winks and we play blind.” The ending:

Who wrongs

us when the body, its own authority, is undone?

Who made the laws of art that the bronze

of the burned man should be shaped by fire?

We spent our day here burning down, drawn

to drink as if to douse the very pyre

here remembered, then to lose our calendared days,

our lined and numbered cosmos, the entire

thing. You were leaving, and left. I remain.

I read it again, then began. I said I could see why the Poet didn’t often write in fixed forms. Even this loose terza rima wasn’t handled very well. He’d chosen it presumably because the poem was partly about forms (the statue, the body, the poem), and forms breaking down, someone burned at the stake, commemorated in bronze, and the lovers’ bodies no longer answering the laws they once did. The iambic pentameter of the first tercet falters in the second. I talked of the kink in the rhyme scheme.

Durant barely nodded. He was waiting to see if I could reach beyond the undergraduate-level answer I’d offered him. I continued.

“The lover being addressed seems to love science. The speaker has a weaker eye for science, and questions art. There are a few tired conceits at work. Fire as a principle of both destruction and creation, of lovers’ passion, etcetera. There’s an ambiguity in the ‘pyre/here remembered’—is ‘here’ the statue, commemorating a death by fire, or is ‘here’ in fact the poem itself, commemorating their lost passion? The meanings coexist. And we get the full sense of that by noting the title. ‘The Art of Memory’ alludes to the art advanced by the man represented in a bronze statue in the very place he was burned at the stake. Giordano Bruno. The poem is set here, in Campo de’ Fiori.”

When I’d first read the lines, months ago, I wondered whose death? whose statue? But reading them now, the answers were clear, though about Bruno I knew only that he had devised elaborate memory systems, and that because of his heretical theories of astronomy he was publicly executed by the church.

Durant raised his glass to me but the test wasn’t yet completed.

“The lover says, ‘The sun winks and we play blind.’ It’s the line that first caught my attention in that sidebar on my screen. Have you heard the expression before?” he asked.

“No. In context—I’m guessing a bit here, the poem is obscure in places—but it might mean that truth reveals itself but we sometimes ignore it. The idea is that the lovers have had a truth revealed to them that they’ve been ignoring but that one of them is no longer going to ignore. Presumably, given the tired figures, the fire and so on, it’s that their love has lost its passion. It’s dying.”

Even when I hadn’t fully grasped the poem I felt the loss in it. After loved ones die, every last antacid ad is heartbreaking. In the first weeks after I was orphaned I couldn’t read poetry or prose. The Londoner brought me back by leading me to Three Sheets, and because so many of the poems either made no sense or were less than excellent, I deputed them to express my emotions for me in little combustions I could smother with cold, analytical words if they grew too hot. One day in that Montreal basement the fire nearly caught me (the stale fire metaphor clearly has) and it took my online rant to extinguish it.

“The poem’s autobiographical, don’t you think?” he asked.

“We can’t possibly know.”

“He’s writing about his experience. Lost passion, lost love. He was here.”

“We don’t know that. To avoid fallacies, we shouldn’t assume he’s writing about his life. Or at least not literally. It’s the safer assumption.”

“So your training tells you. Mine tells me different.”

Some echo in the comment landed me back with the Londoner in Madrid. We ate dinner at a small wooden table, our money and time running out. I’d wanted to tell her that she was the only woman who’d ever inspired me to poetry or song, inspired me to risk failing. I wanted her in words but couldn’t have her there. It was a way of saying I loved her, though of course I would never admit to speech such a worn term as love, and so I felt both love and my inability to say it either straight or slant. She put her knife down and sipped her wine, close-set eyes, soft breath of a face. Before she took up her knife again I reached across the table and grasped her hand up high, near the wrist, and squeezed it. I meant to communicate my love and protection—her life had left her in need of protection from recurrent bad luck—and she looked at my hand on hers, then up at me. She wanted me to say what it meant, this touch. But I couldn’t say a thing, and let go.

Now I sat looking at Durant’s hands. He held one in the other, pressed a thumb nervously into his palm. The certainty struck me that Durant himself was the Poet. Who else would have taken such an interest in my posted rant? If I had to guess—so easily I stepped into the same trap of biographical conjecture—I’d have said the Poet was male, yes, and at least in his fifties, given the recurrent theme of aging as a kind of decline. And a man alone, often addressing an absent “you” who seemed not at all metaphysical. And Durant himself was a genetic biologist, and so might have known a woman with a scientific eye like the lost lover in the poem. And even an anonymous poet must want to meet one live reader.

He sat up slightly higher.

“There’s a poem by Czesław Miłosz, the Pole,” he said. “He imagines this square here, and then takes us to where he’s writing the poem, Warsaw in 1943, during the first uprising. The ghetto is on fire. Outside the ghetto, couples ride in a carousel and the ashes from the fires drift to them in what he calls ‘dark kites’ and they catch them like ‘petals in midair.’ Miłosz has the authority of the survivor, of witness. The poem, as poem, stands or falls on those petals. But because he sees them with his own eyes, the charred petals are floating before us too, in the very words on the page.” I didn’t know what to say. I had no compulsion to say anything. “Whether a poem is about love or historical atrocity, and whether or not the poet was really there, it has to come from somewhere real. Warsaw, this piazza, or a coil in the heart. I know you understand this.”

I understood less as the day went on. We left the café and through the Renaissance streets I followed him, or trailed him, more precisely, his person and his meaning. He allowed anything to come to his attention, voiced every thought and half thought. He must have been very lonely for someone to talk to as he met the city, a feeling I knew from my first visit there. But always I was on guard. The café meeting had been measured and planned, performed. Was he setting me up for more lessons as he stopped and bought us gelato or as we paused before the facade of a church? “Santa Maria dell’Orazione e Morte.” He pointed with his cone to the terrifying winged skulls on the doorway. “The place is dedicated to the burial of the dead. It inspires mortals to pay their tithes and eat their greens.” An underlying seriousness always there in his voice or expression enabled him to joke without disarming awe, even while ice cream melted onto his hand.

“In case you’re wondering,” he said, “and you are, I’m not the Poet. And the job is still yours if you want it.” He was striding again, looking into the ancient stones passing beneath him. “Don’t decide until I show you the apartment.”

Those first days in Rome now in memory seem painted, the perspectives mastered to a mathematical exactness of light and shadow, the Della Francesca’d faces and fabrics somehow colouring even the sounds, the streets, voices speaking a language I didn’t know. A kind of dark comedy crept into the hours. Words became prime elements, reduced not to sense but the urge to sense, the need to say, the need to share in the act of saying. Or maybe it wasn’t quite like that. Sense came in fragments that combined or didn’t, somewhere between Piero and Mondrian. I felt outside of my own experience, not unpleasantly, even as I was included in company. Durant had been absent for most of my first two days in the apartment, but on the second evening he invited me to dinner. We were seven on the rooftop of the apartment building, I, Durant, and five of his acquaintances from the building. Yves was a Paris-based travel writer on sabbatical with his wife, who was Greek and was never properly introduced but seemed to have once worked as a photographer. Their friends Patrice and Anton, a gay couple, both pilots for Air France, agreed about not much except the strength of their pilots union. The only Italian, Carlo, who owned the building, was about Durant’s age. He resembled, it must be said, Mussolini, with even something of Il Duce’s ridiculous bearing, at least when he thrust forward his chin to offer up the final word on Arab uprisings, the compromised Italian press, or the quality of the Super Tuscan blend. He hosted these rooftop dinners for his tenants every second Wednesday night.

Though I’d just started work—my only instructions were to read Three Sheets “for patterns” and to “profile” the Poet, as if we were out to catch a serial killer—Durant had insisted on paying me in advance for my first two weeks. I’d been poor for months, so sitting there with four hundred euros in my pocket I felt good, trusted, valued, but also misjudged, soon to disappoint. Wanting to impress Durant, wanting to misrepresent myself impressively, made me feel younger than I was, needy and lacking in seriousness.

The talk moved between languages—Italian, English, French—until someone remembered me, who spoke no Italian and spoke French like a camp counsellor played guitar, and shifted them all back to English.

“Explain your joke,” said Anton. He was narrow-featured and tended to burst staccato into conversation and then pay no attention to whoever took up his point.

“I don’t think I can,” I said. “It wasn’t very witty. Do you have summer camps in France?”

“We have camps, yes. I thought you said ‘campos.’ A field. I thought you were insulting the farmers’ way of speaking. Or perhaps just the French. When I visit Italy I often hear these insults.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Then you did intend to insult?”

It would be more accurate to say his features were pinched.

“I’m sorry others insult you,” I said.

“You shouldn’t apologize for others. It leads to confusion and disastrous political ennui.”

Yves was asking Carlo about property for sale in Turkey. Carlo’s son would spend his summer away from university studies renovating a building in some gentrifying neighbourhood on the European side of Istanbul.

“The seller was a nervous man who inherited the address from his mother. He saw risk everywhere,” said Carlo. “The risk of Islamicists, reformists, a police state, a racist-nationalist government. Of the surrounding economies, of earthquakes. Stupidly, he told me of his fears. The price for the building was attractive.”

The word that came to mind was retrench. I wanted to go to bed but I saw Durant glancing at me, gauging. He wanted to see what he’d paid for. And now, Yves’s wife was asking me for my feelings about Canada.

I said I had complicated feelings about it. I found it a highly agreeable country, comparatively strong by most meaningful indices, education, health care, crime and penal stats, collective rights protections, and so on, though it had never resolved or acknowledged its abhorrent treatment, ongoing, of native peoples, despite which, given the general failure of nations in their treatment of native peoples, it was the very global example of multicultural success that other countries, especially the U.S., claimed to be the exceptional, exclusive, or pinnacle—pick your figure of speech—examples of. For a few moments as I spoke the others listened but then drifted into other conversations. Even the Greek woman, with the countenance of a listener, seemed somehow to be listening to her left and right. Though he wasn’t looking at me now, I sensed that only Durant was paying attention. And yet, I said, not really aware that I had these precise opinions, compared to most countries with strong educational systems and a history of at least some leisure class, Canada persisted in a cultural adolescence, with a huge, silent gulf between its artists, few as they were, and their audience, brought on primarily by a vapid cultural commentary. All of this complicated by new technologies and a fracturing of the impulse toward serious attention.

“So your experience escaped shallowness.”

I had no idea what she was talking about. It turned out she was under the impression I’d recently visited Canada.

“I’m Canadian, not American.”

“My mistake,” she said. Then she asked if I’d ever visited the United States and what were my feelings. Then she interrupted my nonanswer and asked again about Canada, its vast regions and overwhelming vistas. I brought it all around—a trick I had learned on other trips outside North America—to a few stories about encounters with bears. Suddenly the whole table listened in. The stories weren’t mine, though I put myself in them. The mother black bear following me (my former friend Derek) up a tree in which, I (he) saw too late, her cubs were lounging. The grizzly I (a guy in one of my literature classes whose name escaped me) met on a mountain path, where I (he) froze, unable to back away, until the grizzly turned around and left the way it had come, as if it had forgotten its car keys. The polar bear who walked into the bar up in Churchill, Manitoba, where I (the CBC camera crew) was thawing (their equipment) out. The stories were all implausible and true. I survived in each one. By the time I’d finished them I felt surrounded by a borrowed northern gravity.

Carlo’s son, Davide, arrived, introduced himself to all, and sat across from me. He looked like a buzz-cut soccer star, straight off a poster for the Azzurri. As if we’d been speaking for hours he told me he found Rome tame and dull. He was leaving for Istanbul the next day. He asked if I played music.

When conversing with nonnative English speakers I often have this sense of having missed a transition, and of unexpected echoes. It changes my own way of speaking. I didn’t really know how I’d occasioned the bear stories, for instance, and now I expected bears to return as a topic in some unlikely way, just as guitar playing was about to.

“I play guitar badly, like a camp counsellor.”

“In Istanbul,” Davide continued, “I busk on the great street Istiklal with my friends. We play gypsy style. We’re very good. Even the gypsies admire us. I’ll send you a link.”

In this way my email address was brought forth. On the back of his business card, I printed it like a seven-year-old practising his letters, and handed him his own card. On the front side was a badly drawn figure of a very long-clawed hammer or a very thick-stringed instrument.

I asked Davide what he was studying. He said it didn’t matter. He was going to drop out of school.

“Though I haven’t told my father.”

He said this in full voice, with his father ten feet away, talking to Durant, paying his son no attention. I wondered if Davide hoped his father would overhear him or register unconsciously what he was saying, but then it seemed he simply knew exactly how much volume he could safely get away with, in the way local taxi drivers measured small spaces at high speeds.

All at once the voices fell silent and Durant looked at me.

“James,” he asserted in a voice that made me want to deny that I was James or had ever met him, “your bear stories are amusing but they don’t really display your greater talents.” He said that they’d recently had in their number a Canadian who claimed to be a clairvoyant. She’d announced that they all had known one another in a previous life. “She called herself a seer. And here you are, another Canadian, a seer of subtexts, a maker of connections. I wonder what you’re thinking about all of us.”

Durant valued the idea that he’d been right about me.

“I’m thinking I’d like to be invited back next week and should dodge the question.”

“I wanted to ask her how a clairvoyant knows about past lives,” Patrice said. “Maybe our beloved dead have these Wednesday dinners together, too.”

“We know something about one another”—Durant was still addressing me—“but we’d like to know more about you. Tell us about your origins, your family.”

“I don’t talk about my family.” The words were immediate, sure, and yet they surprised me.

“How intriguing,” said Anton flatly. “One of you must be a monster. Was it Daddy?”

“Then what else is in your heart?” asked Durant. “By ‘heart’ I mean ‘memory,’ of course. Which poems have taken up there? Recite one.”

As I pictured myself pulling the folded euros from my pocket, rolling them tightly, stuffing them down his throat, I tried to fend off the request by reminding him I wasn’t a poet, that my connection to poetry was now professional and so to call it up socially would be to mix business and pleasure.

“I’m sure Patrice has landed many planes in heavy weather but let’s not have him land one here tonight,” I said.

It turned out that everyone at the table had in their hearts and on their tongues a little poetry, or in Davide’s case, banal song lyrics. The poems tended to be very old, things learned in school, I was told, and as they were approximately translated seemed to be full of stale, romantic imagery or clunky metaphors about the stages of life or the horrors of war. When someone forgot a word or line, the others imagined possibilities, sometimes from what were apparently well-known advertising slogans or catch lines from popular television shows. There was much laughter.

Davide sang his lines in a surprisingly good voice, uninflected with earnestness.

Then it was my turn. I had very little to offer. A few years back I had tried to memorize not whole poems but stanzas that I liked. Did I still know them?

I offered a few lines from the American poet W. S. Merwin, from a poem called “The Dreamers.”

a man who can’t read turned pages

until he came to one with his own story

it was air

and in the morning he began learning letters

starting with A is for apple

which seems wrong

he says the first letter seems wrong

They waited me out for a few seconds, expecting more. Yves declared the stanza a “paradox” but didn’t explain what he meant. Durant asked why I found it significant.

“I don’t find it significant so much as…” I almost said “beautiful and true.” “Language belongs to a lapsed world. It can’t quite reach what it grasps for.”

“And yet,” said Durant.

“And yet in this stanza language describes what it says can’t be described.”

“To what end?” Carlo asked. “Language is a problem. We all know this. Poems should be about the heart or the world, not the words in between them.”

“That is a stupid thing to say,” Davide maintained in a calm voice, without looking at his father. He glanced at me apologetically.

“Promise me, son, that you will write a song about the word pollice the next time you hit one with a hammer.”

He said this as I’ve written it, in English except for the Italian word pollice, which I assumed didn’t mean police, though that was the image I pictured, Davide hitting a policeman with a hammer, then singing about the words involved rather than the act.

For a moment father and son looked silently at each other and then Italian broke loose. They spoke rapidly, passionately, almost murderously, until Davide got to his feet and left without saying good night.

Carlo poured Durant and himself more wine.

“I’m sorry for my son. His boyhood will not end.”

The rest of us cast around for suitable comment, found none. Showing great valour, I thought, I stepped into the conversational breach.

“Merwin was unlikely to offend. Or so I thought.”

“Or so. No more bear stories, please,” said Anton.

He tended to address his drink when he said these things.

“What have you pretended to misunderstand now, Anton?” I asked. The others, even Patrice, I noted, seemed delighted.

“I’m not the pretentious one.”

Patrice explained that Anton thought I’d used the Italian word for bear, orso. He apologized for his copilot. I wondered how it was sitting with Anton, this third instance of someone apologizing for another person. Patrice explained that Anton was bitter that Air France had without warning informed their pilots that all communications to towers globally were to be in English.

“His ear for English isn’t precise. He’s worried there will be incidents.”

I pictured Anton, upon the wrong angle of incidence and some misidentified English word, flying a plane into a woods full of orsos. I was exhausted. For three days I’d been reading poems, looking for patterns, hearing echoes. The work survived into my off-hours. What I needed, in fact, was to hear banal song lyrics in a good voice without earnestness, maybe on a beach somewhere with the waves being waves.

I stood, waved, gave a little bow. I apologized to Anton for whatever misunderstanding was about to ensue, thanked everyone for their company and mindfulness of my unilingualism, and walked off, crawled through the dormer, our entry/exit point, which led into Yves and his wife’s rented apartment, which led to the hallway and stairwell and Durant’s apartment, and my hard bed, where shortly I curled up in a dark full of floating foreign syllables.

On my third day in the apartment a woman appeared. As was his habit Durant had gone out for the afternoon and I was at work in the little station he’d prepared for me, a desk with a printer in the corner of my bedroom, with a window to my left looking out at the opposing windows and flaking stucco of the rust-yellow apartment across the narrow street. For only a few minutes in the early afternoons the sun would drift between the buildings and fire them to a light I’d seen before and marvelled at, but never contemplated. In sunlight the walls became the very planes upon which, to their makers, God’s energies met those of common, untabernacled man. I had already come to love that window and the street’s thin slot of sky, and I was sitting with a stack of poems from Three Sheets, waiting for the full sun, when I heard the front door being unlocked and opened. I bent back to the lines at hand, a short poem called “July” that seemed to be telling me something I couldn’t quite hear, when a voice spoke from my bedroom doorway.

“So you’re the new me.”

I turned to find a tall young woman, maybe a little older than I. Her face was slightly tapered, fine-featured. Sunglasses propped on her head pulled her brown-blond hair back to reveal a widow’s peak that returned the eye, pleasingly, to her face.

“I’m Amanda. He didn’t tell you about me.”

“James.”

“Any breakthroughs, James?”

I was trailing the moment, aware of looking, and of her awareness of being looked at.

“A lot of leads,” I said. “I didn’t know anyone else had had the job.”

“Then you weren’t meant to know. He won’t be happy that we’ve met. I won’t tell him if you don’t.”

In their set position the edges of her mouth curled slightly upward so that her expression ran against her tone. They present all at once, the proportions of beauty, but it’s the incongruences that mark them out and steal into us. That’s not at all why Yeats was so attached to the idea that “there is no excellent beauty without strangeness,” but it’s what came to mind.

She delivered unprompted the account of how she had come into Durant’s employ. Seven months ago, just after she’d graduated with a master’s degree in something called Truth and Justice Studies, Durant emailed her with the same job offer made to me. They’d exchanged comments posted at SHEPMETSOR and he said he liked her description of the poems as “mysterious little buildings with their doors ajar.” Durant flew her to France, where he was working, and they both transferred to Rome, just before she quit the job. “We were becoming too attached.” That she said all this so freely, so fully, and so soon upon meeting, should have left me wary of her, but she seemed without guile.

She excused herself and went about watering plants while I sat staring at the doorway where she’d appeared, failing through vertigo to connect my recent life in a Montreal basement to the one I was now living, though in both all I seemed to do was read. My first impression of her hurt slightly, in that I was sure Durant must have realized upon meeting me how far short I fell of Amanda’s easy confidence, and very likely of her abilities. I am twice as present on the page as in person. If the same was true of her, then compared with mine her interpretive skills must have been of a different order of sophistication. Besides which, she had studied Truth and Justice, two nouns in that category of words I’m ashamed to utter for my lack of service to them as principles. Only the shame counted in my favour.

In a minute Amanda came in and watered some fern-looking thing beside the dresser.

“August doesn’t notice plants. If I don’t do this, they’ll die. It’s why I still have a key, our last arrangement, though I think he’s forgotten it. I doubt he knows when I’ve been by.”

“You only come by when he’s out?”

She finished watering and stood there, just beyond arm’s reach. I had not been this close to a woman paying attention to me since I was last in Europe.

“It’s easier. He’s out every afternoon. I see him sometimes for dinner. He likes to know that he hasn’t stranded me here.” She now worked in a bar that catered to Americans. In time she intended to head north to The Hague, where she had some connections, to see if she couldn’t scratch up some social justice internship for one of the tribunals. She made it sound like migrant labour. She held a dented tin watering can. “What are you working on? Can I ask?”

I told myself it would contaminate the experiment to reveal my thoughts—for this reason Durant left me alone by day—though in truth I was afraid she’d be unimpressed. I was considering the possibility that the poems were posted in an order designed from the outset rather than randomly, which would mean that, because certain details seemed to allude to current world events, elsewhere in each poem would be lines that had been preselected. Upon this idea, I was extracting the most telling words in a few poems I’d marked by the date of their first appearance on the Three Sheets site. And I’d come to one that held me in its little mystery, door ajar.

“Do you remember ‘July’?”

“Let me think. A swimming pool. And a bird. What else?”

Rather than hand it to her I pulled the poem out and slid it to the edge of the desk. She put down the can and moved one step closer. I read along with her, my eyes on the poem, my focus caught in lonely adolescence.

That summer the heat wouldn’t quit

and the water in the 1963 blue

concrete pool climbed

to 89 degrees a robin

appeared on a branch in the stairs

landing window with so many

twigs in his beak so symmetrically

held that he presented long

whiskers and a helmet of horns,

looked, in fact, like a Kurosawa

character. I am telling you

they were exactly measured

and held just so by a force

whose agency is at work again

now in this question you ask of me,

its dimensions concealed from you.

Ridiculous, really, the

accidents of likeness,

that you should want to know

the magicked secret of it all.

“Right,” she said, “ ‘the magicked secret.’ ”

“It’s beckoning us to solve a mystery. The poem’s showing us the concealed dimensions but we aren’t seeing them. Or at least I’m not.”

She was still focused on the page, but she blinked, deliberately.

“The poem is complete,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

Now she looked out the window. The rooftop shadows claiming the walls meant I’d missed the minute of perfect light. She took hold of the pot with the ferny thing and held it up in front of her.

“Let’s not name this plant.” (I couldn’t have.) “Let’s look at it. We can touch it, put it in different lights, care for it. But we don’t ask what it means.”

I was looking at her, not the plant, but she kept holding it, so I looked. It was, all in all, a plant.

“Yes,” I said. “Well, I don’t think the Poet is at quite the same level of creative power.”

She set down the pot.

“The speaker in the poem is writing about the mystery of likeness. In any given case, is the likeness of one thing to another an accident or not? He’s been asked a question he doesn’t want to answer, which means there is an answer, and yet there’s the mystery of the memory it brings on, the bird unknowingly having made a new face for itself. That’s all, it’s complete.”

“You think I should just let the poem be.”

She picked up the page and was handing it to me when the light through it revealed the notes I’d made on the back of the sheet. She turned it over. I watched her read. Date of the pool, hot summer, house with a landing, thermometer reading in Fahrenheit. So a U.S. American house. Two-storey. I picture it mid-twentieth century. Not suburban, maybe somewhere in the West. Can’t say why I think this.

“I should be going. Will you look after the plants now?”

“I’ll forget them, too. I know that much about myself. Why did you quit the job?”

Her expression shifted minutely—toward doubt?—and she looked down to the page in her hand, as if surprised to find it there, and handed it back to me.

“These poems,” she said. “The moment you touch one, turn it over, it gets ahold of you. Whether he admits it or not, that hold is why August gets up in the morning. It’s what he doesn’t know that matters to him, not the answers to puzzles. He thinks he wants to find the Poet, who he’s convinced lives in Rome—it’s why he’s out every afternoon, playing hunches, sitting in cafés, staring at the people gathering at statues—I bet he pulled that trick on you, too, didn’t he? ‘The Art of Memory’ in Campo de’ Fiori?”

“Yes.”

It was all much bigger than poetry, she said. Durant was convinced that the Poet possessed something of his, a great, specific loss.

“What are you talking about? What has he lost?”

She took the can and walked back to the living room. Watching her walk away only intensified my wish to follow her meaning. She stopped and turned and seemed to be having an argument with herself. The winning self nodded and spoke.

“ ‘The sun winks and we play blind.’ ”

“Is the poem quoting someone? Who said it?”

“He did.”

“Who did?”

“August. To his daughter. In their last conversation before she went missing. Three years ago.” She winced slightly to hear herself. She had come to the apartment to say exactly as much as she’d said, but she was betraying Durant. “Don’t tell him we’ve met. Or you can say we’ve met but that we both insisted there be no talk about the poems.”

A missing daughter. Durant had impressed upon me the seriousness of the work, but I hadn’t quite believed it connected to anything real. I stood and started toward her. She drifted away slowly so that my path pushed hers to the doorway.

“Missing how? Did she run away?”

“He gives few details and there’s nothing online. She was in her thirties. She seems to have walked out of her life and never reappeared. Private detectives found no trace. Then there’s me, and now you.”

“How did you learn all this? Is it in the poems?”

“He told me in one short, drunken conversation. I found nothing of her in the poems.”

“What about the sun winking?”

“I don’t know. Maybe a coincidence. Or maybe he thinks he coined an expression that in fact he overheard. Maybe it’s out there, circulating like an old penny.”

The words in her answer impressed themselves visually. I pictured the coin in coincidence and then saw the penny and it dropped.

“You’re not telling me everything. I need the whole story.”

Whether the whole story was Durant’s or hers, she seemed to be calculating the cost of telling it, reading numbers on some invisible meter. She offered to meet me the next afternoon in the park of the Villa Borghese. She pulled the sunglasses down over her eyes, a way of announcing her exit, or of preventing me from reading something in her face.

My life falls to its rhythms, some common to many, some mine alone. Breaking the rhythms, taking my eggs poached for once, changing the route to a job, choosing to stop loving or stop failing a loved one, I inscribe a new line in my brain. It’s the patterns that I can’t get outside, whether I recognize them or not, that define me. To see my specific self—sorrows and fears and pathologies—reflected in external reality effects a recognition. Some such moments calm me. Others do me in.

My father was a military man. He and my mother had taken early retirement in a town near the base in Nova Scotia where he’d last served. I grew up many places but this last town had become familiar and I knew it wouldn’t be lost to me as the others had, even if, and sooner than I imagined, it would come to contain the greatest loss.

One week each summer and Christmas, Montreal to Nova Scotia, back.

In every sense he was a hard man to know.

My parents were United Church Protestants. When they both turned sixty-two they moved to Turkey for a year to work for an NGO in a refugee camp near the Syrian border. The circumstances of their deaths were ambiguous. They were found sitting inside their car on a dirt road, a few kilometres past the last cotton field, where the stony desert took up, dead of blunt force trauma. I had the accident report sent to me and translated. In separate sections, it described the conditions of the vehicle and of its occupants. I read about the car but only glanced at the second section, not allowing myself to read left to right, up to down. Instead I cast my eyes over the words, registering random phrases. The white Kia outwardly showed no evidence of having hit anything. Inside, matters were different. My parents seemed to have met a very sudden stop. They were dashed on the dash, steered into the steering wheel. Neither had been wearing a seat belt, a detail underlined by hand in the original document, as if to explain their fate or to blame them for it, yet they always wore seat belts and the car’s annoying reminder bell was in working order, a signal detail, though what it signalled I didn’t know.

Normally, they were buckle-up folks, my parents. Resourceful, tough, good in crises. They strapped themselves in, lashed themselves to masts in storms. In their third week at the camp one of their colleagues was killed when his car, leading a van of police officers to a food-collection point, tripped a thousand-pound bomb placed under the road by the PKK, Kurdish separatists “agitating” for a homeland. Before the day was through they’d contacted the man’s wife, a woman in Pennsylvania they’d never met, and arranged immediate support for her, somehow collecting names and numbers of the couple’s family and friends. After which my father set out himself, on the same road, overland at the bomb crater, to organize and secure the food transport.

There were dangers everywhere. A Turkish nationalist group in the area had been implicated in the murders of Christians, some of them foreigners, and Al-Qaeda and ISIS had begun setting up thereabouts to promote their specific lunacies across the border, inside the civil war in Syria. I asked them to return to Canada but my mother said, as if she had no say in it, “Your father wants to see this through.” For him, the world was complicated but life was not. Life was an enactment of duty to principles. He regarded my central passion—literature—as an indulgence, unforgivably inward. The inwardness was a kind of selfishness, even a cowardice. When I started graduate school he was warily proud, and my quitting it confirmed his assumptions. He believed I would never have a steady job, let alone a career, and whether or not I married, would never surrender my self-indulgence to the building of a family of my own. In so many words, he said all of this, said it once, on what would become our last Christmas Eve together. With some embarrassment, some pride, I’d produced at the table a little magazine in which I’d had three poems published, a magazine of the kind read only by the other contributors, though my parents wouldn’t know that. My idea was to suggest I was making some headway in the writing world. My mother hugged me. I can still feel her bracelet pressing into my back. He looked at the poems, not seeming to actually read them, said I was just “playing a game,” and announced he had to say his piece.

I was hurt but not angry. I still don’t know if he was right. I’ve written just one poem since. That night I tried to tell him in words other than these that I agreed, that to write poetry is like playing a game, a board game, but it’s play in service of the real, a game in which the win is the defeat of the game itself. In the last move the gaming piece (imagine a stone) leaps from the board into the world, the real, the physical, a red quickness, the actual, and the game becomes a kind of miracle, rules broken and laws suspended. It’s a lesser miracle, but one connected to the greatest of them, the creation of life itself, in which inanimate material, a stone (imagine a gaming piece), is struck into consciousness and set down in the home space, the world.

“Words,” he said.

The final word was his. Though he’d worked his whole life, and lived modestly, my parents’ worth when they died was under six thousand dollars, not enough to cover their funeral and the estate lawyer. It was months before the NGO, on an audit, discovered the missing funds. Near the time of their deaths my father stole from the organization almost forty thousand lire. His defenders argued he must have been paying protection for the organization, though no one could say to whom. Other details emerged. Expensive new windows and a stack of rugs and blankets in their apartment in Gaziantep. A tight schedule of doctors’ appointments for my mother. Everything seemed telling at one moment, meaningless another. To repay the missing funds, the organization sold their car, still in good working order.

Fourteen billion years ago the universe began with form but no predictability. In time, patterns formed. Complex systems. Life. And inside it all—I hear it—howling chaos.

Durant called my cell later that afternoon to ask that I meet him for dinner in Monti, near the Santa Maria Maggiore. It was only while I was in the taxi, as the driver called out to friends along the street, as if Rome were a village, that I had enough distance from Amanda’s visit to think clearly about what I’d learned. If Durant saw allusions to his daughter in the poems, he would want to test his readings—he was a man of science, after all—but there existed no empirical measures of meaning in language or art. Had he brought in Amanda, and now me, to confirm that the poems had something to do with his daughter or to rescue him from going over a final edge?

I’ve been calling her “Durant’s daughter” but before I left for dinner I played detective and tried to hunt up her name. There was nothing online so I called Larunda and spoke to what sounded like the same program assistant I’d spoken to days earlier. I said I was from the Petros One Group, a(n invented) private insurance company, and that I had to file something on behalf of August Durant but was unable to reach him. Again I met with resistance. “I just need to finish a form,” I said. “A certain interval has passed and I need his daughter’s first name. It’s illegible on the document I have.” She said, “No chance.”

He was waiting for me at a window table, more than halfway into a bottle of red wine. The moment I sat down I sensed someone had preceded me. He received me with his usual warmth but did I detect a slight strain in his smile? Or was it that I saw him differently now? His voice was already full, but crisp—there was no suggestion that the wine had brought it forward—so maybe someone had been sharing the bottle with him. And then, yes, I noticed the stain of a red drop on the tablecloth, under the edge of my plate.

“I hope you haven’t been waiting long.”

“Not long. Have you had a good day, James?”

“I can’t say. There’s no way of taking my bearings.”

“Well, let’s stop working, then. Have a drink and let the mind unclench.”

Durant’s side of the conversation was wonderfully far-ranging. Tracing how exactly a comment about the wine had taken us to serial-killing lions, I found that his connections moved associatively, playfully, like my cha-chas, rather than logically. The route went more or less from the 2008 Le Cupole Rosso Toscana to its label’s colour of red like those in the frescoes in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme to cave paintings to the life of cave dwellers to the fear of cave bears to predator habits to anomalies within predator populations to serial-killing lions. By the time he took a pause we were onto a second bottle, our plates were lined with small rabbit bones, and it was time for dessert. What struck me then was the size of the man’s passions. He took a huge interest in the world but his enthusiasm was disciplined. His nature wasn’t acquisitive so much as embracing. When he held up his glass he seemed to read the properties not just of the wine’s colour but of the light that revealed it. He wanted to know life in all its registers. How else could someone who had suffered such a loss let himself be opened by poetry?

“When did you first learn of Three Sheets?” he asked.

So we hadn’t stopped working after all.

“A girl I was living with told me about it.”

“How did she come across it? Could you ask her?”

“We’re not in touch. Likely someone sent her the link.”

He nodded.

“They say it’s organic, the way information travels on the internet. But it’s not. It lacks the full range of human emotion and intent, the nuance of the conversational gambit, or the necessity to share that binds a speaker and listener. I must sound like your grandfather.”

“Studies show a decline in oral skills among young people in recent decades. And so-called social skills. Sort of what you’d expect.”

“But you have the skills, James. Where did you learn them?”

“I don’t know. I was very shy growing up. I learned to listen. Then in school I learned to converse, debate. I had a few professors who expected words on demand.”

“And so you have political skills, wouldn’t you say?”

“I’ve never thought of them as political. I try not to play angles on people.”

“And yet when you sat down here, you asked if I’d been waiting long. It wasn’t simply a polite inquiry, was it?”

It was what my mother used to call a “God-in-the-garden” moment, my thoughts rendered naked and ashamed.

“I sensed I was entering upon someone’s exit.”

“There’s your sharp intuition at work. You sensed an absence, someone missing.”

“I suppose. But it’s no concern of mine.”

“And so why ask the question? It must be that you wondered if I was meeting someone specific, someone you know. Am I right?”

“If you weren’t right then I’d think you were paranoid.”

“You’ve met those in the building. But who else do you know in Rome except me?”

“I’m not sure how well I know you. Maybe I know no one.”

“There, you see? A politician’s answer.”

He took an interest in the dessert menu and recommended the amaretto semifreddo with chocolate sauce.

“She likes you,” he said. I took a sip of water to stall the moment, as if the gesture might help me decide what to think, but the motion of my hand up and down seemed only to give away what I felt. Confusion, a tinge of guilt, anger. “She thinks you’re better suited for the job than she was.”

“There are no innocent conversations, are there? Drinks on the piazza, dinner on a rooftop, and here now, it’s one constant performance review.”

“She’s not an investment analyst. But I’ve been right to put money on you.”

“A spy, then.”

“Not a spy either. This afternoon I remembered about her watering the plants. I invited her here and sure enough she’d just met you. She says you looked at one poem together but she wouldn’t give you a reading.”

“Did she tell you which poem?”

“You doubt what I’m saying, but she wasn’t spying. We have to trust each other, James. I’m relying on complete honesty from you.”

“But you won’t tell me what I’m looking for.”

I wondered if it was hard for him not to tell me about his daughter or if the undisclosed story sheltered him, the unsayable private in the place of telling all. I was the one being duplicitous. There was nothing good about the feeling, except a kind of self-punishing guilt I didn’t understand but was used to.

“I don’t tell you out of respect for scientific method,” he said.

“A politician’s answer.”

He smiled.

“Write something up by the end of the week, just a report on what you’re seeing, even if it’s not much.”

“I have to say, August, I’m beginning to think this isn’t even about the poems.” So I was being dishonest, trying to open an angle. “It’s like I’ve been selected for training toward a job I can’t know.”

“Maybe I’m a guide of some sort.”

“Or a spymaster.”

“Spies again. I hope your other hunches won’t come from the movies. Your objective, ours, is to solve the mystery of the poems.”

He topped up my wine. I was learning his conversational habits, the way he’d counter anything that might seem a criticism of me with a kindness. But the kindness itself was often complicated, reminding me who was paying the bills, so he wanted the criticisms to stand. It was hard around Durant not to see myself as I imagined he saw me, a young man with ideas and plenty of feelings but few convictions. And not so young as to excuse the fact that I engaged with the world more fully through the mediating plane of language than I did directly, standing in the rain in an ancient city, as he’d found me the previous night when I’d gone out for a walk and gotten turned around in the streets near his apartment, and ran into him by accident (or so he said) as he was out to buy coffee. He led me back under his umbrella, talking about the patterns of Roman rain. He must have seen that even my willingness to challenge him was only a way of pretending to gravitas. We were both aware that at any moment I might be lifted by a breeze and carried away.

The next morning I began to write a profile of the Poet. In the forty-three poems so far posted at Three Sheets, he presented two personae. One of these, evident in just four poems, could not be biographically approximated. The voice was genderless, its concerns not at all personal, and in fact seemed intent on superseding the personal to play a kind of avant-garde jazz, drawing its notes mainly from pop culture, history, the languages of one arcane knowledge or another, and the sounds of pure nonsense.

The dominant voice in the other poems, I still thought, was of a likely white, likely North American male, in his late fifties or older. These poems tended to be in free verse, lyric, prose-dominated, with similar line lengths, the occasional suspended syntax, small tensions formed at line breaks, variously parsed, annotated, or end-stopped. Often the reader was wrong-footed, then rebalanced. Because of their little mysteries the poems managed to be slightly larger than they seemed, but much depended on whether or not the mysteries were earned.

On questions of poetic principles, the two voices could not easily be reconciled. The suppositions underlying them, about language, convention, the very nature of meaning, these were opposed to one another. And yet I felt sure that the poems were the work of the same (very likely) man. What they shared was the woman described, addressed, or remembered, a woman I now couldn’t help but think of as Durant’s daughter. It was possible to construct a montage of stills about her, a few dramatic scenes. Sometimes she was even quoted, as in “The Art of Memory” and in what I thought of as its sister poem, “In Cities.”

Seven cities in three years with this same

street holding light at the penned

unseen dog’s angle of howl. Turning left

out the door, then west at the fourth

corner will run you past the same

bar with the tree overhanging

the parking lot and the women’s darts league

playing for keeps on Tuesday nights.

Much of this, imagined and half-forgotten,

imagined and said and they’re serious, the darts.

They’re in the air here tonight,

where the barkeep serves the house wine in

flasks, and the parking lot is an

alley lined with mopeds,

the tree a tree, and the howl is in the

pitch of the roofs opposite just now

catching what you once asked while

looking off at them. “How many lives

can I walk away from?” Meaning

not yours, as I thought, but others’,

mine. And I had no answer for

you or the penumbral rim of lighter

red around the drop you’d spilled

on the white cloth.

I got up from my desk. I’d read the poem maybe two weeks earlier, but somehow the last lines hadn’t come to mind the previous night when I’d seen the wine stain, like a drop of blood on the restaurant linen. Because the slightly uncanny coincidence had to be meaningless, I attributed it to that suggestible mindstate we find ourselves in when travelling or reading, in which days fold on themselves upon synchronicities. Many people know the feeling, one that in the past I had tried to disarm with research. But the explanations for coincidence—probability analysts talk about anomalous statistical clusters, mathematicians predict the logical frequency for seeming miracles, psychologists speak of cognitive bias—are all inadequate. Such moments are among those we file away as interesting and inexplicable, and best not made too much of in conversation if we don’t wish to be teased by others who pretend not to know what we’re talking about. I told myself I should expect such echoes, given that I was both away from home and reading intensively, which is to say, there was a lot of the world streaming through me.

Part of that world was Amanda. I’d failed all morning not to be distracted by our planned meeting. What revelations might she have for me today? She had knowledge I wanted and a confession to offer, should she decide to tell me about her meeting with Durant. For the first time in months I looked closely at my face in the mirror, a good way of quieting my imagination and resetting expectations. I’d always hoped I’d be more attractive as I aged—my best features are character ones, the squared-off eye-nose combo, the mouth a notch too wide and disrupting the line between chin and barely pronounced cheekbones—but still in its youth the face was unremarkable and, I thought, a bad champion of my capacities.

On my way out of the building I ran into Carlo. The top buttons of his safari shirt were undone to display a jointed necklace made of some nacreous stone polished to the same reflectiveness as his bald head. He asked where I was going and offered a lift. His car was parked in a gated courtyard on the next block. The moment I saw the ’65 Aston Martin I knew it would be our topic of conversation. He asked if I recognized it. I said James Bond, and so on. We discussed Ian Fleming, his favourite author.

“People think he was just a writer,” he said. “But first he was a war hero, a man of action.”

I said that, in fact, Fleming was the hidden commander behind the Dieppe Raid that killed nine hundred Canadians in 1942. The raid was a disaster, poorly planned and supported, and the losses were viewed by some as a cover for an attempt to steal one of the German four-rotor Enigma machines used by Axis powers for passing coded messages. It turned out Carlo knew about Enigma machines, too, about the Italians’ failure to update their naval versions before World War II, and the British intelligence successes in cracking the code. He had no time for fascists, he made a point of saying. One day, he said, he’d show me a painting of Bletchley Park that hung on his office wall.