AROUND 2.30 A.M., Sunday, 19 July 1942. Kapitän Teddy Suhren stood on the bridge of U-564 as first one then two explosions ripped through the night sky some 800 yards away. Red, green and yellow jets of flame flashed into the air, followed by a huge, rolling fireball, which lit up the sky like daylight, silhouetting not only the two stricken vessels, but much of convoy OS34 from Liverpool to Freetown in West Africa – supplies that were heading to the North Africa front.

Two ships had been hit, but it was the Empire Hawksbill that was now literally disintegrating before his eyes. All thirty-seven members of her crew and nine gunners were incinerated in the massive fireball. Now the pressure-wave from the explosion swept up towards the U-boat, as a mass of colours continued to light the sky and reflect in the inky Atlantic. ‘Flying debris rains down from even more explosions,’ wrote Suhren, ‘smacks into the sea all around us, and makes fountains of water shoot up a metre high.’1 Suhren had already sent the crew down below and ordered the U-boat to speed away as swiftly as possible. In all his long years as a submariner, he had never seen anything like this; he found it curiously mesmerizing and could not bring himself to leave the bridge.

Then suddenly, black as a raven, a frigate swept past between them and the burning ship. Immediately, Suhren shouted down to the official photographer from the Propagandakompanien der Wehrmact, who had been forced upon him for the trip.

‘PK man!’ he shouted.2 ‘Quick, quick, to the bridge!’

To his horror, however, instead of the photographer poking his head up, he heard air escaping from the dive chambers and realized the boat was starting to dip at the bow. What the devil was going on? Realizing they were starting to dive, he quickly clambered into the conning tower and only managed to pull down the hatch as a wave of water sloshed over him.

‘Have you all taken leave of your senses?’ Suhren yelled at the Navigating Officer. ‘Whose job is it to give the alarm on board?’

‘But, Boss,’ stammered the man, looking completely taken aback, ‘you gave the order yourself.’

Suhren now realized what had happened. Calling down ‘PK man’ had been misheard as ‘Alarm’. He was still annoyed, but chose to take it out on the photographer instead. ‘You stand around and get under everyone’s feet,’ he yelled, ‘but if there is anything out of the ordinary to film, you’re nowhere to be found.’ It would have been, Suhren told him, the scoop of the war.

Meanwhile, they had now dived to around 100 metres when in the silence of the boat they heard the sound of propellers overhead and moments later the ASDIC began to ping, ping, ping rapidly. Suhren turned to the Leitender Ingenieur (LI), or Chief Engineer.

‘Flying shit,’ he said, ‘they’ve found us. LI, down to 150 metres.’

From the listening room, reports were stated calmly, quietly. More than one ship was hunting them. A noise like a broom with iron bristles as one of the vessels swept overhead from astern. Three corvettes. Suhren couldn’t understand why they hadn’t attacked, and then in almost the same moment there were five explosions, not so very far away. These damn depth charges, thought Suhren, they get more and more dangerous. But U-564 seemed to be all right – no leaks.

‘Listening room,’ said Suhren now, ‘in a few minutes they’ll attack again. To judge by the prop noise, they’re coming from astern. When the escorts get close, let me know at once. LI, as soon as he makes his report, full ahead and hard to port. Pull the boat up then, and as soon as we’re at 60 metres, blow tanks. Yes, don’t look so worried; we’ll chance it. We’re going to surface and go for it. I’m not just going to sit here and get hammered.’

On cue, five more depth charges exploded a few minutes later, but further behind them this time, and now the boat was rising, as though pulled by a string. Suhren stood under the hatch and, as they surfaced, he opened it up and looked out. The freighter was still burning but he could see the three corvettes and it was clear they hadn’t spotted them. The diesels fired up noisily and they were off, the distance growing. In no time they were doing 16 knots, but to get a bit more speed Suhren ordered the electric motors on as well.

They had now been seen and flares were fired, lighting them up. Beside Suhren, the 2WO ducked automatically. A star shell burst, casting another swathe of light before fading, then pitch blackness descended once more. More star shells followed, but the U-boat was now speeding away at 17 knots, too fast for the pursuing corvettes. Suhren was just beginning to breathe more easily when, to his horror, he realized the diesels were stopping and thick black smoke was coming from the hatch.

‘Boat unfit to dive,’ reported the LI.

‘What do you mean, “unfit to dive”?’ called down Suhren. ‘Alarm! We must dive – there is no alternative. Take her down and let’s get away.’

They managed to get her to dive, but as Suhren returned back down the tower he could not see his hand in front of his face; the boat was in darkness and everyone was coughing and choking. He couldn’t understand why the emergency lights hadn’t come on. Pressing a handkerchief over his mouth, he now heard, as they all did, the tell-tale sound of propellers again. Suhren looked up – they were right on top of them now – but then, mercifully, they swept on past until eventually the ping, ping, ping of the ASDIC was barely audible at all.

Playing safe, Suhren kept them down another quarter of an hour, then surfaced. The Atlantic was now still and clear once more: they had got away with it.

The emergency lighting flickered on and, with the hatch open and ventilators on, the smoke soon cleared, although it left a black film on everything. Suhren demanded an explanation, but the LI was unable to help; it was the mechanic who revealed all.

It turned out an oily rag had been left on a ledge above a bend in the exhaust pipe. With all the twisting and turning from taking evasive action, it had fallen off on to the exhaust pipe, which by then had been glowing red hot. The rag caught fire and fell into the bilge, where a fair amount of oil was swilling around; it caught fire in turn and developed into a full-scale blaze. They were able to open the ventilation valve, which flooded the bilge and put the fire out, but only with a mass of smoke filling the boat. One small oily rag had very nearly done for them all.

As it was, they had survived, and with two more sinkings to their names. Rather than point fingers, Suhren decided instead to hold a ‘coffee party’ regardless of the tight crew rations and to make a small speech. ‘It’s perfectly clear to me,’ he told them, ‘that God didn’t just have a hand in this but an entire arm.’ Everyone had kept their cool, no one had panicked and the LI had handled the boat in an exemplary way. ‘It was,’ he told them, ‘a remarkable achievement. Now I can celebrate our success with the rest of the crew – even the mutton-head who left his cleaning rags on the ledge.’ He was, he told them, proud of them all.3

What he hadn’t told them, however, was that this was to be his last combat patrol. After this, his sixth in command of U-564, he was to be given a rest and then to become one of Dönitz’s trainers. Suhren, like his friend and fellow commander Erich Topp, had done enough; it was time for them to pass on their experience and expertise.

Even so, as the night’s drama had reminded him all too clearly, serving in a U-boat was a dangerous occupation and becoming more so as Allied ASW technology steadily improved. And for Suhren and his crew, there were still many long days to go before this patrol was over.

For all the new technology, however, much still rested on human judgement, and for the British there was more terrible folly of leadership to come – this time at sea – which would add to the humiliations and tragedies of the Far East and the failure at Gazala.

Convoy PQ17 to Murmansk and Archangel, consisting of thirty-five merchant vessels, had sailed from Iceland on 27 June carrying 300 precious aircraft, 600 tanks, 4,000 trucks and trailers, and enough materiel to equip a force of 50,000 men. It was the biggest convoy ever sent to Russia, on what was already proving an extremely hazardous supply route. In winter, conditions were so bad a man would freeze to death in the water in seconds. By summer, the cover of darkness had gone; in June, there was daylight every hour of the day and the convoy route was within reach of the Luftwaffe.

To protect it was a naval force of two British and two US cruisers and three US destroyers, while the British Home Fleet had also sailed in support of the operation and was trailing it some 200 miles behind. On board the US heavy cruiser Wichita was Lieutenant Douglas Fairbanks, Jr, who had been asked by Admiral Giffen to carry out the same role he had performed on Wasp – that of report-writer and observer.

Unbeknown to those in the convoy, it had been quickly picked up and trailed by a U-boat and Admiral Dönitz swiftly dispatched two more. Icy fog protected the convoy as it inched its way across the Arctic, but then on 2 July it cleared and the first air attacks started. Late on the 3rd, Fairbanks recorded a signal that had been received: ‘At 1900,’ he noted, ‘an Admiralty message, just broken down, confirms our previous report: the Tirpitz, the Hipper, and four large German destroyers have left Trondheim.’4

Back at the Admiralty in London, the First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound, had already warned the escorts about the possibility of the German surface fleet emerging from the Norwegian fjords – it was a risk they faced with every PQ convoy – and had told them categorically not to engage any German force that included Tirpitz. Rather, should it venture out, they were to shadow it and try to lead it to an interception with the Home Fleet.

Now, Ultra decrypts suggested Tirpitz was on the move, which, as far as Pound was concerned, could mean only one thing: that the German battleship and other surface fleet had left port, would evade the Home Fleet, then soon catch up and slaughter the convoy.

Meanwhile, the convoy had been making good progress, and not until 4 July did the German attacks press home with much success. That afternoon, some twenty-five bombers arrived, including one piloted by Major Hajo Herrmann, now a Gruppe commander and operating from Kemi in northern Finland. There was cloud about as he and his men dived. They descended lower and lower, emerging into the clear from under the blanket of cloud. ‘Small black, brown, and grey bursts of smoke on our starboard hand,’ noted Fairbanks, ‘are seen like sudden splatters of mud against an eggshell sky.5 Seconds later we hear the sound of gunfire. A new attack is on.’ Then he spotted what looked like ‘small fast bugs skimming just above the waterline.’

These skimming bugs were Herrmann and his Gruppe of Ju88s. They dropped their bombs, then swiftly climbed back into the sun, leaving the smooth white sheet of cloud over the convoy below them. ‘Suddenly,’ wrote Herrmann, ‘it was pierced by a dark-coloured cumulus, which rose high into the sky as if from a fire-spewing volcano.’6 This was one of three ships that were hit.

Another attack developed later in the evening; by now two ships had been sunk and a third damaged. From the bridge of Wichita, Fairbanks breathlessly recorded: ‘1829: A plane is falling in flames – it crashes near us! Great blinding flash of fire – seems hundreds of feet high – then black smoke.7 Big cheer from Wichita crew. We think we are responsible. Now the cry, “Go get the bastards!” More explosions and the sickening “whoosh” of the fire. Looks like a merchant ship is hit badly. Fat smoke curling skyward. Another Nazi plane dives in flames.’

Then suddenly, when everything seemed to be under control, a signal arrived ordering the escort force to withdraw westwards. This was followed twelve minutes later by a further Admiralty signal: ‘Because of threats from main enemy surface forces, Convoy PQ17 is to disperse and proceed to Russian ports.’

Fairbanks and all aboard Wichita were gobsmacked, but assumed Tirpitz must be about to appear at any moment. Without their knowing, Pound had called an emergency meeting of his operations staff and asked each one in turn what they would do in light of the limited intelligence they had about Tirpitz having left port. To a man, they were against dispersal, although Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Moore suggested that if they were going to order the convoy to scatter it was best not to waste any time. In fact, Pound had already made up his mind. And so the fateful order was given.

In fact, Tirpitz was not at sea; rather, had been merely moving berths. Why Pound acted in the way he did – why, frankly, he panicked – has never been understood. It has been suggested he was already suffering from the brain tumour that would kill him the following autumn; others have thought he was in the midst of some kind of breakdown. At any rate, it was the wrong order – a catastrophic decision.

‘We hate leaving PQ17 behind,’ noted Fairbanks.8 ‘It looks so helpless now since the order to scatter came through. The ships are going round in circles, like so many frightened chicks.’

Without their escort and without the scale of the convoy to help protect them, the scattered ships could be picked off piecemeal. Whatever strength they had had in numbers was gone.

The inevitable slaughter followed. Learning the news, Grossadmiral Erich Raeder, C-in-C of the Kriegsmarine, then did order Tirpitz and his surface force out, but when it became clear that the U-boats and Luftwaffe had the task of PQ17’s destruction in hand, he ordered the battleship back to port once more.

By the time the very last ship made port at Archangel on 28 July, twenty-four of the thirty-five that started the voyage had been sunk. That was more than two-thirds of PQ17, and included 120 men dead, plus 210 aircraft, 430 Sherman tanks, 3,350 vehicles and almost 100,000 tons of other cargo all lost. For the Germans, it had demonstrated that Tirpitz could cause the destruction of huge amounts of Allied shipping without even the risk of leaving port. For the British, it was yet another embarrassing and humiliating episode that was shaking the confidence of all – of the Russians, the Americans and those at home too.

It was time for the rot to stop.

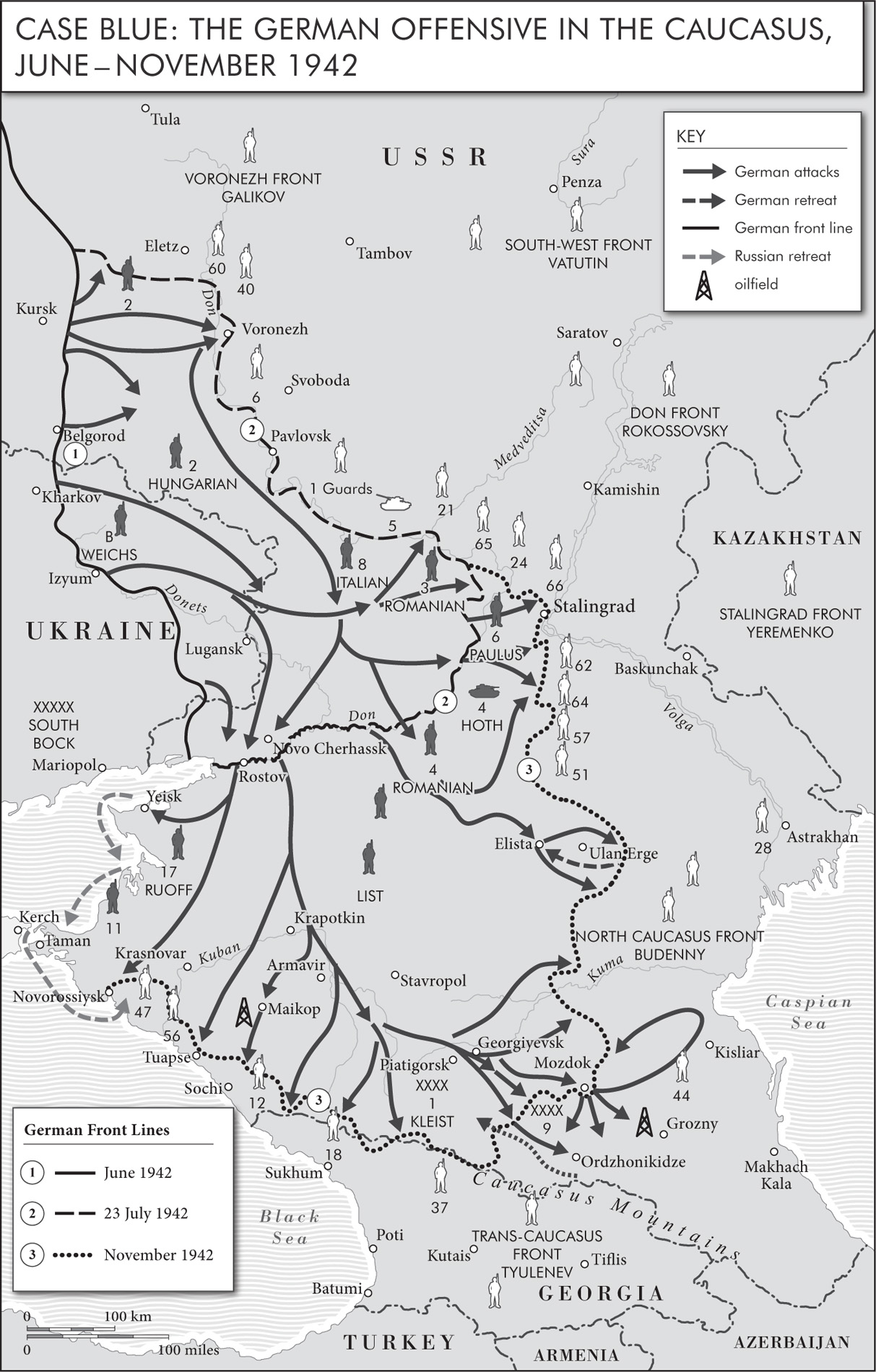

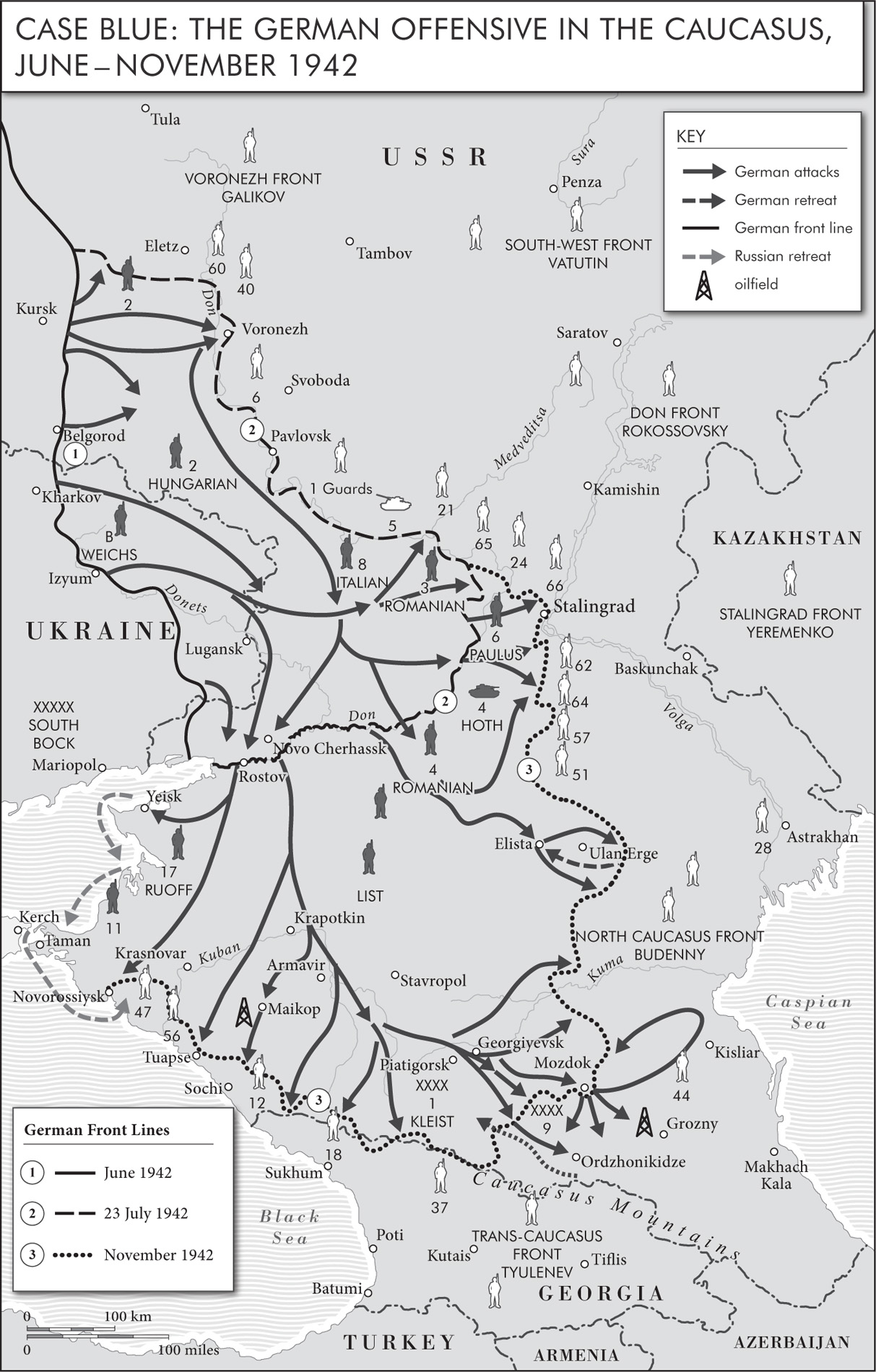

On the Eastern Front, Case BLUE, the main German summer offensive, long in the planning, was launched on 30 June, more than a year after BARBAROSSA. On one level, confidence had been restored by the triumph at Kharkov, as well as by the preliminary operations to clear the eastern Crimea, which had gone well for the Germans – although Sevastopol did not finally fall until the beginning of July.

On another level, however, there were a number of signs to suggest Case BLUE was just a little bit too ambitious. To start with, the German forces amassed for the task were still short of just about everything. Generalmajor Balck’s new division was not the only one expected to attack under-strength. In fact, at the OKW, General Warlimont had received a paper from his staff on 6 June called War Potential 1942. It was quite frank about the Wehrmacht’s shortcomings. On 1 May, the armies on the Eastern Front were short of some 625,000 men and there was no hope of making good the losses of the 1,073,066 casualties so far. The panzer divisions in Army Groups North and Centre were so short of tanks they could field only one battalion each – that is, around 40–50 panzers per division. ‘Mobility is considerably affected by shortage of load-carrying vehicles and horses which cannot be made good,’ continued the report.9 ‘A level of demotorization is unavoidable.’

In fact, Army Group South, the spearhead for Case BLUE, had only 85 per cent of the trucks needed. Luftwaffe units were now at only 50–60 per cent of their establishment, with 6–8 aircraft per Staffel – squadron – rather than the 12 they should have had. That meant total strength for the Luftwaffe was still lower than it had been on 10 May 1940. In terms of manpower, the 1923 class had already been called up – that is, men now as young as eighteen who at that age would normally have been expecting to be doing their Reichsarbeitsdienst – Reich Labour Service; in other words, they were being thrust into action eighteen months ahead of time. ‘Serious shortage of raw material for tanks, aircraft, U-boats, lorries and signal equipment,’ it continued, before concluding, ‘Our war potential is lower than it was in the spring of 1941.’10

Even the plan for Case BLUE was more prescriptive, more detailed and more complex than anything that had come before it. There was no longer the strength to mount simultaneous attacks in the south and north around Leningrad, as had been originally envisaged. Instead, the attack in the south would happen first, then, once successful, men and materiel would be transferred north. What’s more, because the forces available for Case BLUE were so tight, Hitler had decided they needed to be very carefully controlled. Panzer formations were not allowed to get ahead of themselves; there would be no more charging off like Rommel and Guderian had done in the past. Case BLUE had also been divided into four successive operations, each with a very precise timetable. Since timetables invariably went up the spout the moment a battle began because of the inevitably large number of variables brought by the fog of war, this was also a cause for concern. That flexibility of command and manoeuvre, such key features of Bewegungskrieg, were being stifled, in part by Hitler’s micro-managing style and in part by the chronic shortages that appeared to leave them little choice.

Finally, the intelligence picture was once again woeful. Göring still had his Forschungsampt, his own private listening service with which he ensured he kept one step ahead of his rivals, and the SD still had an iron grip over most subjects of the Third Reich, yet when it came to the intelligence picture of their enemy, Nazi Germany was, bar some few notable exceptions, woefully bad. Underestimating enemy strength had worked against them during the Battle of Britain and now, two years on, they were making the same mistake again. For example, they estimated the Soviet Air Force had 6,600 aircraft when they had nearly 22,000; they thought the Red Army had 6,000 tanks when actually they had 24,446.11 In artillery pieces they were even further out: an estimate of 7,800 guns when in reality there were more than 33,000.

At around two in the morning on 28 June 1942, Generalmajor Hermann Balck was at his 11. Panzerdivision command post. They were on the left flank of Army Group South and were due to move towards Voronezh. Outside, all was calm – the night air was still and silent. Then suddenly, at 2.15 a.m., their own artillery barrage opened up. Even a man of Balck’s experience was impressed as dust and smoke enveloped them and the night calm was shattered. Russian counter-battery fire quickly replied, but soon after his men were moving forward. By 9 a.m., the bridge across the first river obstacle had been set up by the engineers and, in an echo of Guderian at the Meuse, Balck was among the first to cross. While under fire, he went forward to see his infantry regiments before following on in his Kübelwagen with the panzers. ‘It was an intoxicating picture,’ he noted, ‘the wide, treeless plains covered with 150 advancing tanks, above them a Stuka squadron.’12

His own division was entirely successful and within a few days they had reached and crossed the Tym River, even though, to his annoyance, too many of the Russian tanks and guns appeared to have got away, pulling back and successfully withdrawing out of the fray. In Russia, as in North Africa, space could be readily ceded if it meant men and materiel could be preserved; the Russians were learning that. This time there were no vast encirclements.

None the less, all along Army Group South’s front, Case BLUE appeared to be going well, as the main thrust now surged south towards the Caucasus. As news of these successes reached the Wolf’s Lair, so Hitler became increasingly agitated. One moment he was dreaming of a vast link-up between Axis forces now in North Africa and those pushing south through the Caucasus. The next, however, he was worrying about his western flank and insisted both on keeping one of the precious panzer divisions in France and sending another now to join it on the Western Front. He was also micro-managing once more. Halder was tearing his hair out with frustration as the Führer insisted on interfering at every turn. Against Halder’s direct advice, for example, he had concentrated too many panzer divisions against Rostov, leaving the flanks dangerously exposed. No sooner had these movements taken place than the folly of the decision became all too apparent. A fit of rage then followed. ‘The situation is getting more and more intolerable,’ noted Halder.13 ‘This so-called leadership is characterized by a pathological reacting to the impressions of the moment and a total lack of any understanding of the command machinery and its possibilities.’

Hitler always interfered when he was anxious. With Rommel’s success and with the early signs that Case BLUE was going well, it must have seemed as though ultimate victory really was possible. However fantastical this remained in reality, it felt tantalizingly close to Hitler – which made every setback, small or large, seem that much worse.

As it was, by the end of July, German forces had smashed the Soviet South Front and, thereafter, the German advance was rapid. For Case BLUE, Army Group South had been further bolstered and so split into Army Groups A and B; huge German forces had been amassed for this renewed drive to the Caucasus. Maikop, a major objective, was captured on 9 August by General von List’s Army Group A, although the significance of its capture was marred by the destruction of its oil installations by the retreating Russians. At the same time, the German Sixth Army under General Friedrich Paulus was advancing further east towards Stalingrad, on the major River Volga. By 10 August, after reinforcement by the Luftwaffe who had been supporting Army Group A, German troops had reached Stalingrad’s outskirts.

By then, however, the advance south was beginning to slow as supply lines once again lengthened and Soviet resistance grew. Vehicles were breaking down, spares were harder to deliver, as too was fuel; the distance that Germany’s mobile armoured units could operate was necessarily limited. Hitler could talk of creating a mammoth Axis link between Egypt and the Caucasus, but this was a pipe-dream; the Wehrmacht was simply not equipped to cover such distances. Rather in the same way that an aircraft had an operational radius, so too did the Army. Give or take, it was about 500 miles, but that was really stretching it; around 300–350 miles was a more practical limit – and that rough rule of thumb applied to the desert too. That was the culmination point, after which its speed of operation slowed down massively, giving the enemy the chance to regain its balance.

As it was, although they were within touching distance of those Eldorado-like oilfields at Baku, the Germans might as well have been a thousand miles away for all the good it would do them even if they did get there. Hitler’s plans for an even larger Greater Reich, stretching from the Caucasus to the Middle East and into Egypt, were the stuff of fantasy, not least because of the logistical problems it would involve: the lack of roads, the lack of infrastructure, the absence of shipping, the inability to transport oil back to Germany. The world was not criss-crossed with oil and gas pipelines in 1942. There were pipelines, but most of those in the Soviet Union were still out of reach; there was one between Maikop and Grozny, but that was not much use to the Germans. There was another from the Guryev oilfields on the northern shores of the Caspian Sea, some 350 miles further east from Stalingrad, which led to Orsk in the Urals. And that was about it. There was none heading west towards Germany. How was the oil going to be transported, even if the wells had not been destroyed as they had at Maikop? The already overstretched Reichsbahn did not have the capacity to deliver it. Incredibly, no one within the Reich appears to have thought about this.

Rather, the best they could hope for was to disrupt Soviet oil and armaments production. The capture of Baku, the third largest oilfield in the world, would certainly have been a severe blow to the Soviet war effort, but their remaining oilfields – those at Guryev and at Beloretsk, some 600 miles further east of Moscow – still provided them with more than Germany received annually. What’s more, because Hitler chose to accept over-optimistic appreciations, which in turn were based on faulty intelligence, he began Case BLUE truly believing the Soviet Union was at the limit of its military and economic strength. Little did he realize that Stalin had already ordered much of Russia’s war industry to relocate further east, especially to the Urals. Here, those few oil pipelines and a comprehensive river and rail network had enabled Soviet armament manufacture to continue with far greater efficiency than German intelligence believed.

Furthermore, because the Luftwaffe did not have the aircraft either to spy on or to bomb those plants in the Urals and Siberia, they were, to all intents and purposes, blind to the reality. ‘Russia, if it used its entire steel production for armament purposes,’ reported the OKW’s War Economy Department, ‘would at best, temporarily, achieve approximately the same output figures as the German armament industry in the army and Luftwaffe sector.’14 This, in fact, was nonsense. Lend-Lease from the USA and Britain, the use of substitute materials and the highly effective industrial move eastwards all ensured that, far from being on their last legs, ever-more arms were reaching ever-more divisions of the Red Army. The gulf between German expectations and reality was enormous.

Nor was Case BLUE the only German effort. Hitler had not given up hopes of taking the still-defiant second city, Leningrad. The Russians, however, were proving equally determined to hold on. Grim though the situation remained inside the city – as many as one million had perished since the siege began almost a year before, a barely comprehensible number – the summer had meant the ice over Lake Ladoga had melted. As the Allies were well aware and as the Germans were discovering, the most efficient way to deliver supplies of any kind was – and remains even to this day – by ship. More than a million tons of supplies were shipped across Lake Ladoga, while over half a million civilians were evacuated and 310,000 troops brought in, along with large numbers of guns and ammunition. It was these guns, together with those of the Baltic Fleet, that were able to silence German fire early in August during a defiant first performance in the city of Shostakovich’s newly composed Seventh Symphony, ‘Leningrad’. To all those who braved going out to watch this extraordinary performance, the Leningrad Philharmonic played in perfect unison with the Russian guns. At any rate, not a single German shell fell nearby that night and the concert was broadcast around the world.

For the planned renewed German attempt to take the city, General von Manstein had been sent north with his six-division-strong Eleventh Army and three massive siege guns. The intention was to attack towards the north coast to the west of Leningrad, neutralize the island of Kronstadt, from where Russian naval guns had been firing since the very start of the battle, then, with luck, sweep east into the city itself. Unusually since Hitler had taken over direct command of the Army the previous December, von Manstein was given a free hand to conduct the offensive as he saw fit. It was codenamed Operation NORDLICHT and was due to be launched at the end of August.

The Red Army, however, pipped the Germans to the post, launching their own offensive on 19 August and once more from the Volkhov front to the south-east – and in so doing proved they had still more depths to their manpower and ability to wage war on a massive front. No matter how many men, guns and tanks the Germans put into the field, the Soviets appeared to be able to produce more.

In terms of liberating Leningrad, it was not much more successful than the Red Army attack back in January, but von Manstein was forced to send most of his divisions south-east to help stem the Russian advance and his plans for NORDLICHT were completely scuppered. Hitler was furious. Red Army losses were over 100,000, but the Germans suffered another 26,000 casualties – the best part of two entire divisions, losses they could not afford.

And all the while, Hitler’s micro-managing continued, making an already difficult series of operations even more challenging. List’s essential air support, for example, was taken from him to reinforce General Paulus’s drive on Stalingrad with the Sixth Army. This was mission-creep. The Caucasus oilfields, and particularly the largest site at Baku, had been the prime objective of Case BLUE, but now, it seemed, Stalingrad had become the Führer’s most important target. On 24 August, meanwhile, Stalin ordered the city to be held at all costs and sent his favourite troubleshooter, General Georgi Zhukov, the commander who had defended Moscow, to co-ordinate the defence. By then, however, the German offensive was once more running out of steam.