‘GENERAL ROMMEL WAS our great hero of the summer,’ noted Else Wendel in Berlin.1 ‘In July he achieved the final victory in North Africa, or so we thought.’ Once more a spirit of hope and even jubilation returned. Yet as the new field marshal was well aware, he had come close to a truly significant victory but had not quite managed it, and the difference between success and failure was massive. In fact, his sensational capture of Tobruk was looking like a smaller version of the German victories in the East – stunning and devastating on a tactical level, but strategically not enough to be decisive. It was no good winning battles if you didn’t win the war.

In the old days, in Norway, France, even the Balkans, and even way back in Frederick the Great’s day, these victories had been possible because, ultimately, the distances were slight and the general staffs knew their operational reach. Victory had been achieved in one surge forward. In the vast expanses of Russia and North Africa, that operational reach was no longer enough. The system could not cope: Germany did not have enough motorization, enough oil, enough shipping. They did not have reliable allies who could make meaningful contributions to final victory. They had reached their culmination point.

In Britain, the joint staffs, across the services, of two coalition partners were working together to launch the largest amphibious invasion the world had ever known. There was plenty to iron out, lots of doctrinal and cultural issues to resolve, and a fair amount of grumbling and grousing as well. None the less, there was also an atmosphere of co-operation, of determination to work together and to get the job done. The contrast with the hapless German planning for SEALION, the proposed invasion of Britain back in 1940, for example, could not have been greater. And there was the contrast of the German–Italian alliance.

Since the start of the war, Germany had repeatedly looked down her nose at her Axis partner. Occasionally, Hitler and von Ribbentrop could demonstrate a little bit of gracious charm towards the Italians, but only when it was felt absolutely necessary and when they wanted something from them. Kesselring had worked hard to be affable and accommodating to the Commando Supremo – the Italian General Staff – in Rome, but he was most definitely an exception; the rest of the time, Hitler, especially, repeatedly snubbed Mussolini, keeping him in the dark about plans, ignoring suggestions and advice, and regarding him with thinly veiled contempt.

Il Duce had hardly done much to earn greater respect, but now, in the North African desert, the German–Italian partnership was about to take another big dip. Following his failure to break through the Alamein Line, on 12 July Rommel wrote a report to the Army Operations Department and referred to ‘alarming symptoms of deteriorating morale’ in the Italian ranks.2 The Italian Pavia and Brescia Divisions had been all but wiped out in the recent fighting and Rommel claimed that ‘several times lately’ the Italians had deserted their positions. As a result, Rommel was pleading for more German troops.

When the Italians learned about this report it went down very badly indeed, not least with the newly promoted Maresciallo Ettore Bastico, the senior Italian commander in North Africa, and with Mussolini, who had given up waiting to march into Cairo on his charger and had gone back to Italy. During his three weeks in Libya, Rommel had not called on him once – justifiably, since he’d been in the thick of battle, but such excuses didn’t really wash with Mussolini. ‘Naturally,’ noted Count Ciano, ‘Mussolini has been absorbing the anti-Rommel spirit of the Italian commander in Libya, and he lashes out on the German marshal.’3 The attitude of German troops was also, apparently, obnoxious. ‘The tone of the Duce’s conversation,’ noted Ciano a few days later, ‘is increasingly anti-German.’4

The truth was, everyone was exhausted – mentally and physically, Rommel included – and this was made worse by the sense of bitter disappointment and even panic at the current situation. Rommel’s troop strength stood at 30 per cent, panzers at 15 per cent, artillery 70 per cent, and the all-important anti-tank guns at 40 per cent. He desperately needed new supplies of everything, otherwise he faced complete defeat; but his supply lines were now desperately stretched, while those of his enemy had been drastically shortened. Moreover, he was keenly aware that more Allied reinforcements were on their way. As it was, a US heavy bomber group, the 98th, was now operating from Egypt, while an American Fighter Group, the 57th, had been temporarily attached to Coningham’s Desert Air Force. More Sherman tanks were also on their way, as were more guns, as well as additional British divisions and armoured units, including the now combat-ready Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry, who were part of the 8th Armoured Brigade.

Rommel viewed the next few weeks as a race against time, in which he needed to rapidly build up strength before the British forces became overwhelming. This being so, and with a shipping schedule firmly in place, he hoped to launch one last, decisive strike against Eighth Army before the end of August.

One of those now working to improve Rommel’s supply situation was Leutnant Hans-Hellmuth Kirchner, who was just one of the pilots urgently now brought in to create an air bridge. Posted to Kalamaki, an airstrip south of Phaleron in Greece, he was given an He111 to fly that had had its bomb bays loaded with fuel containers. On 12 July, he flew directly to the landing ground at Fuka in Libya in a trip that took three hours. Once he had landed, the fuel containers were carefully unloaded with a pulley system and poured into the empty barrels waiting for him. On each flight, he managed around 1,000 litres. ‘If you compare that to the amount that we needed for this long flight ourselves,’ he noted, ‘it was not much, but it had to be done.’5 Kirchner was somewhat taken aback by the chaotic scenes at Fuka: dozens of planes landing on a huge, flat, sandy clearing in the desert, literally in every direction. Army tankers and even panzers simply filled up right beside them as they unloaded. ‘Everyone was very worked up,’ jotted Kirchner. ‘In Athens, the punishment for stealing or selling fuel was death and it was wasted and splashed around. It was insane.’

As soon as he had unloaded the fuel, he took off again and flew back to Greece, this time to Eleusis near Skaramangas. The next day, he was back again, and the scene at Fuka was even more chaotic. Now he flew to Heraklion on Crete, refuelled and remained there overnight before being diverted to Benghazi for his third trip to North Africa. There, both Kirchner and his Heinkel broke down – he with dysentery and the plane with battery failure. By butchering several wrecks at Benghazi, they managed to get the plane up and running again, and on the 16th Kirchner succeeded in holding his bowels in check just long enough to get them back to Eleusis.

Reinforcements of men were also on their way, including the 164th Light Division, currently on Crete, the Ramcke Fallschirmjäger Brigade, and the Italian Folgore Paracadutisti (paratroop) Division, one of the better Italian units. Among them was 22-year-old Luigi Marchese, a section commander in the 2 Regimento Paracadutisti, who had originally been called up as an ordinary soldier and posted to Libya in 1939, before Italy entered the war. Back then, he’d been based in Tripoli, working in the post room of Maresciallo Balbo’s headquarters and then as a military map-maker. With the outbreak of war, however, he had volunteered as a paratrooper, hoping for a bit more excitement and a more soldierly role.

Two years on, and he and the division were posted to Yugoslavia, where occupation and maintaining the peace had been left to the Italians and, since January that year, the Bulgarian 1st Army. Yugoslavia had become a frightening place. One of the mish-mash countries created in 1919 after centuries of Ottoman and Hapsburg rule, it was ethnically and politically divided. Resistance had emerged almost immediately – from the Nationalist, Royalist but almost entirely Serbian Chetniks under Colonel Draža Mihailović, and from the more pan-Yugoslavian Communist and Soviet-backed Partisans under Josip Broz, known by his nom de guerre, Tito. Then there were the Ustaše, who were Catholic, ultra-nationalistic, right wing and Croatian, led by Ante Pavelić. They had been around since 1930, but after the Yugoslav surrender had declared Croatia an independent state, though they included Bosnia and Herzegovina within their new boundaries. Although they were then forced to accept the Treaty of Rome, which annexed part of Croatia into the Reich and part to Italy, they were left to govern this new state without much interference. Since then, their militias had been steadily cleansing their territories of Serbs with some of the most horrific violence yet seen in the war.

For the Italians, the Balkans and Greece had provided lots of territory, but they had proved an endless drain on resources that brought few, if any, benefits. There were no large reserves of natural resources, no wealth, no riches to plunder. All they were doing was ensuring Mussolini’s territorial footprint was larger than it might otherwise be and preventing the Allies from reaching the precious Ploesti (and German-controlled) oilfields in Romania.

The Folgore had been based in Ljubljana in northern Yugoslavia, part of the territory annexed by Italy. Luigi Marchese found it a place of brooding menace. Posters had been pasted over almost every wall threatening reprisals for partisan action. ‘From there,’ he noted, ‘we learned as much about the actions of the German and Italian troops as we did about the crimes that the partisans, including women, committed against unwary or lone soldiers.’6

Marchese had been expecting a long posting in Yugoslavia, but they left this broken country of civil war and rampant partisan activity after only a few weeks, so that by the end of July they were now in another country reeling under the occupation: Greece. Marchese was shocked to find the civilian population so short of food; he had never seen so many beggars, all of whom seemed to be women and girls. He was struck that there were almost no men to be seen at all.

From Athens, they were flown by German and Italian air transports to Tobruk on 1 August and their battalion then sent to Jebel Kalakh at the southern end of the Alamein Line, where they began furiously digging in, and where Allied Air Forces seemed to bomb them almost continuously. Marchese wondered where their own Regia Aeronautica and the Luftwaffe were.

In fact, after a few days in the line, it was horribly clear that the division was under-equipped. Marchese could not see how they had any attacking capacity at all. Rations were poor and the flies were unlike anything he had ever experienced; millions of them swarmed everywhere. ‘The absence of drinking water,’ he noted, ‘is like a scourging from God: not even a litre a day in temperatures of 50 degrees Celsius in the shade.7 The water comes in jerry cans, the taste and smell of which are the source of the disgust and ill-effects on our health that affects us all.’

The challenge remained getting supplies safely across the Mediterranean. In July, Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park had been posted to Malta and within a couple of weeks of his arrival the RAF had regained air superiority over the island. The 10th Submarine Flotilla was also returning there, while torpedo bombers from the Middle East were able to use the island as a staging post. Furthermore, because the Axis were sending convoys to Tobruk and Benghazi as well as Tripoli, those were well within range of Allied bombers. Crossing the Mediterranean was now a great deal more dangerous for Axis convoys than it had been back in April and May, when only a fraction of their supplies had been lost.

Now serving on the Italian destroyer Corsaro was the young sailor Walter Mazzacuto. In the middle of July he was part of an escort group consisting of four torpedo boats and four destroyers whose task was to shepherd just four merchant ships across the Mediterranean. Soon after leaving Brindisi in south-east Italy, they came under attack from RAF Beaufort torpedo bombers and one of the merchant ships was sunk. It happened to be carrying a number of troops heading to North Africa, but most were rescued by nearby air-sea rescue vessels. The convoy continued, pulling into port at Taranto and collecting another merchantman. No sooner had they set sail once more than they spotted a British reconnaissance Spitfire overhead and sure enough, not long after, a formation of Beauforts attacked them again. Another merchant ship was hit, but this time, after working to repair the damage, they were able to keep going and safely reach Benghazi.

The pattern, though, was repeated on Mazzacuto’s next convoy duty. Leaving Brindisi on 3 August, on the second morning at sea they spotted a British reconnaissance plane overhead. Immediately, the alarm claxons were sounded and the men spent all day at their battle-stations, waiting for an attack. Suddenly, at around seven o’clock that evening, US Liberators from the 98th Bombardment Group appeared and began heavily bombing them. Fortunately for Mazzacuto and his comrades, the Americans attacked from far too high an altitude and their bombs fell wide, although spectacularly.

Further waves of aircraft followed, however. At around 11 p.m., another formation of enemy bombers came over, lighting up the convoy with flares and dropping both bombs and torpedoes. The convoy went into a defensive formation, splitting into three groups and covering themselves with a smokescreen. Another wave of attackers followed in the early hours but, much to the Italians’ relief, not one ship was hit. ‘The convoy reached Benghazi on the morning of 5 August around 11am,’ noted Mazzacuto, ‘and without a further attack.’8 This convoy, at least, had safely reached North Africa.

Supplying the Panzerarmee was principally left to the Commando Supremo, because the Germans had no shipping of their own and because supplies were going from ports in Italy to Italian ports in Libya. During July, on the insistence of Rome, most were being sent to Benghazi and Tripoli rather than Tobruk or tiny Mersa Matruh. This policy appeared to pay off because only 5 per cent was lost in July and 91,000 tons reached Libya safely.

This was not as good as it sounded, however, because the Panzerarmee needed around 100,000 tons of supplies a month at the front, not 1,300 miles away in Tripoli or 800 miles back in Benghazi. The supply chain was using half the fuel landed just getting these supplies to Egypt. As July turned to August, Rommel now insisted more supplies be brought direct to Tobruk and Mersa Matruh, and fuel was his most urgent requirement. For all his tactical flair, Rommel had a very large blind spot when it came to logistics. Fuel was so tight because he had overreached his supply lines. That limit of operations of around 350 miles still stood as true as it always had since the start of the war. Now he was overly reliant on excessive – for the Axis – fuel supplies.

‘The battle is dependent upon the prompt delivery of this fuel,’ Rommel told Maresciallo Cavallero.9

‘You can begin the battle now, Herr Generalfeldmarschall,’ Cavallero replied. ‘The fuel is already on its way.’ On its way, yes, but whether it would safely arrive at the front was another matter, yet only if it did would Rommel have any chance of making the decisive breakthrough – a breakthrough he was now planning for the end of the month.

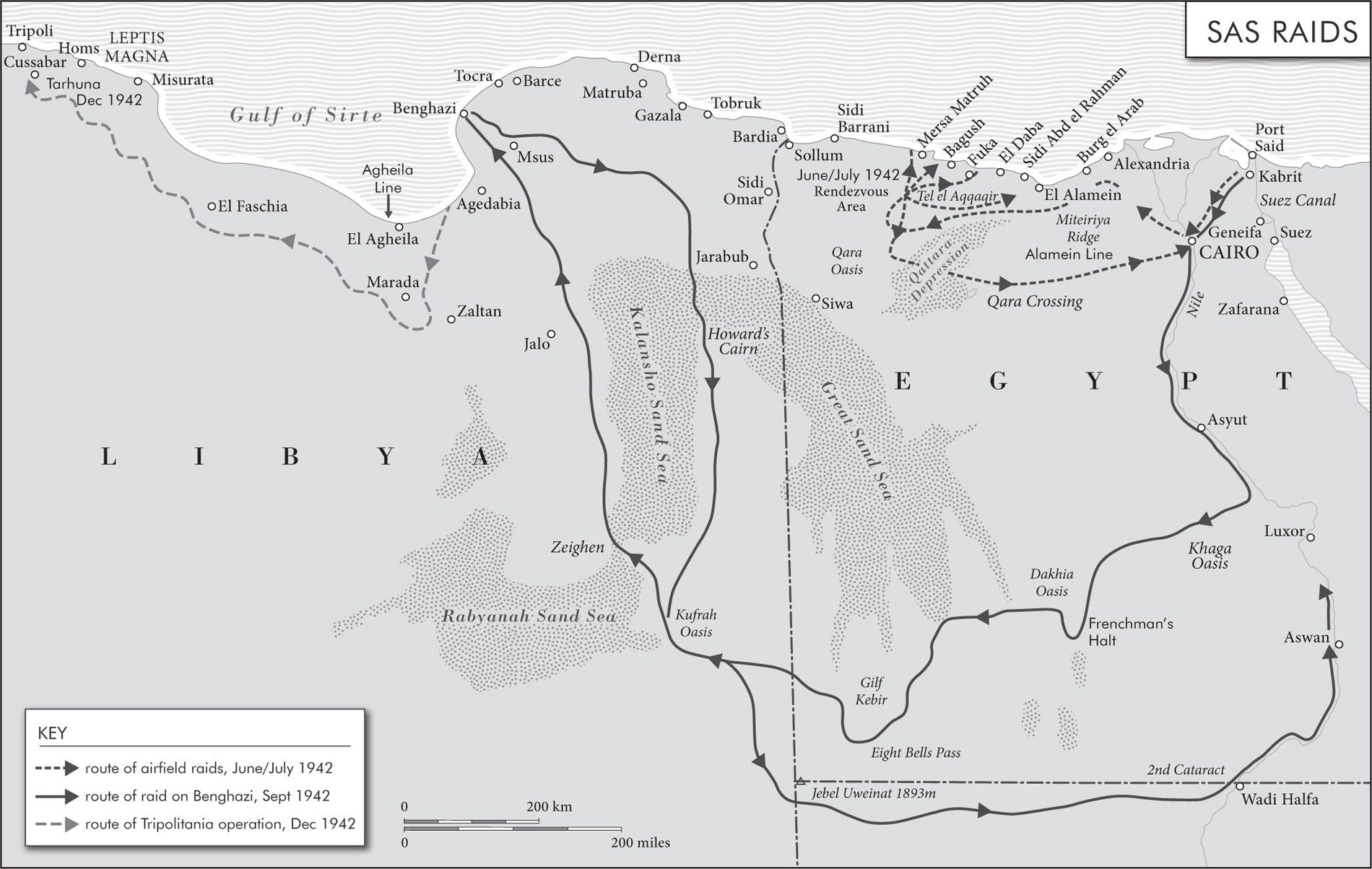

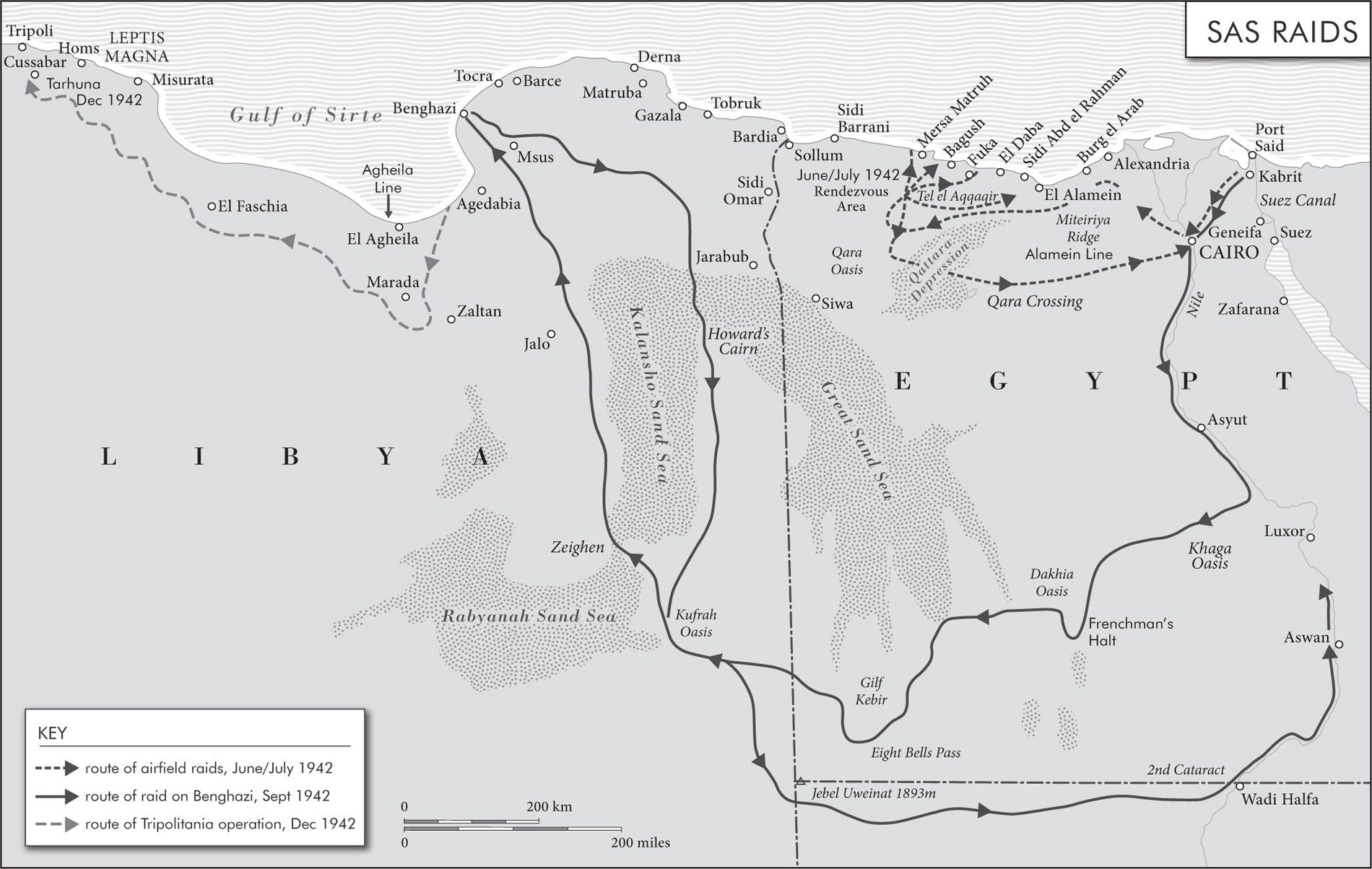

Another factor in building up the strength of the Axis forces in North Africa was making sure they held on to what they had once it was theirs and not allowing it to be frittered away. This, however, was becoming increasingly difficult for the air forces, as their workshops and landing grounds were being frequently attacked by marauding groups of the SAS, operating far behind lines. Eighth Army’s senior commanders might have been tactically moribund but, in sharp contrast, this small band of unorthodox warriors were demonstrating a degree of dash, initiative and tactical flair that had not been evident in British forces since the days of General O’Connor, the C-in-C of British troops in North Africa until his capture back in April 1941.

Since their disastrous first attempted raid back in November 1941, the SAS had grown into an extremely effective force. They had done away with airborne drops and instead had been driven across the desert by the Long Range Desert Group, whom the SAS now renamed the ‘Desert Taxi Company’. During the CRUSADER battles, just twenty-one men had managed to destroy 109 aircraft at airfields near Sirte; the only dark point had been the loss of the inspirational Jock Lewes when he was strafed and killed by a Messerschmitt 109.

Other successful trips had followed. For the most part, the SAS men tended to operate in small teams. Johnny Cooper, promoted to sergeant, had been placed in David Stirling’s team and in March they had destroyed a long column of fuel tanker lorries at Benghazi. A couple of months later, they had attempted to attack ships in port and had driven, in broad daylight, straight into the town, had holed up in an empty house and been thwarted only by broken valves on their inflatable rubber canoes. They had then driven out again. Accompanying them on that raid had been Randolph Churchill, the Prime Minister’s son; it had been breathtakingly reckless, but they had got away with it. They also got away with a raid on the Luftwaffe repair depot at Benina, where, in June, they had destroyed aircraft, hangars and fuel dumps. Climbing the escarpment afterwards, they had paused to watch the fireworks as the time-fuses burned out and the explosions began. One Me110 had caught fire and its cannon shells then ignited, fizzing around the airfield like light flak. Then the petrol dump exploded and hangars caught fire. ‘The effect,’ noted Cooper, ‘was stupendous.’10

The SAS had expanded as a result of these successes to about 100 men strong, including a squadron of Free French, but their task now was even more pressing: to cripple Axis air forces as much as possible behind the Alamein position. That meant travelling down into the Qattara Depression, then up and out again behind enemy lines to the landing grounds at El Daba and Fuka. As had become usual, planning took place at Peter Stirling’s flat in Cairo – David Stirling’s brother was Third Under-Secretary at the Embassy. The idea this time was to take a number of trucks with them so they could be self-sufficient for several weeks. They also now had their own transports: new US-built Jeeps, quarter-ton 4x4 four-man vehicles, which they then stripped down and adapted by adding a .50-calibre machine gun and twin Vickers guns.

A column of some thirty-five vehicles headed out into the desert, and after a brief conferral at Eighth Army HQ they headed into the Depression. Around 150 miles behind enemy lines and some 60 miles south of the coast, they made their temporary base camp, camouflaging the trucks and taking good cover in a series of ridges around the north-west of the Depression at Qaret Tartura. This was their planned base for the next month. It was from here that they began making raids, usually in groups of three vehicles. The first set was on the airfields around Fuka and Bagush and was co-ordinated so that their bombs all exploded at 1 a.m. on 8 July.

Johnny Cooper had set off once again with David Stirling and, as a first, with Paddy Mayne. ‘Young Cooper’, as Stirling always called him, was the navigator, while Stirling tended to do the driving. While everyone else now had Jeeps, the commander’s car was a much-loved Ford V8, which had been captured from the Germans and christened the ‘Blitz Buggy’. On this occasion, they attacked an airfield full of Italian CR.42 biplanes, although they had clearly not destroyed them all, because at dawn the following morning, as they were approaching a long, wide wadi – a dried river bed – two CR.42s suddenly appeared and attacked them first with bombs – to no effect – and then with machine guns. ‘Abandon ship!’ Stirling called out as an enemy plane bore down on them.11 They all ran for it, but as Cooper hit the ground he heard the Ford erupt into flames. ‘We shall have to get another Blitz Buggy, Sergeant Cooper,’ Stirling said to him cheerfully once the planes had gone.

Of more concern to Cooper was the loss of his precious navigation logs and his theodolite, an important navigational tool. Gathered up by the other two Jeeps, they were safely back at the base later that afternoon, although because of reconnaissance planes spotted in the area they then shifted their base 25 miles further west to Bir el Quseir. All in all, the SAS teams had destroyed more than thirty aircraft and between thirty and forty vehicles, although, much to his annoyance, Eighth Army HQ had sent Stirling a signal not to touch the airfield at El Daba. This, it later transpired, had been a mistake.

While Paddy Mayne made another attack on Fuka, Stirling now planned an assault on the former British landing ground at Sidi Haneish, about 30 miles south-east of Mersa Matruh. Worried that if their attacks followed the same pattern, the enemy would prepare appropriate counter-measures, Stirling was always looking to try new attack methods and now decided they should hit El Daba en masse in two columns of ten vehicles each, with Stirling leading in the middle.

After a live-ammunition practice in the desert, which Cooper, for one, found excruciatingly deafening despite the distance from the enemy, and after carefully loading and preparing their Jeeps and weapons, they set off at dusk on 26 July, Cooper navigating the entire column. After a little more than two and a half hours, they had reached the edge of the airfield when suddenly runway lights came on and an aircraft came in to land. Switching off their engines, the SAS men paused and waited a moment, then Cooper stepped out and gave the two column commanders Stirling’s orders, which were to follow him and form into their columns. Engines started once more and then they were off. Stirling drove straight into the middle of the airfield, heading right down the centre of the runway with aircraft lined up on either side. Then the blasting began.

In moments the entire airfield was ablaze. Italian machine guns opened up on them, but the aircraft obstructed their aim so only occasional bursts came anywhere near the SAS men. At the top of the airfield, they had turned and were heading back down on a different track when the Jeep came to a shuddering halt. ‘What the hell’s wrong?’ Stirling shouted.12 Cooper jumped out and opened up the bonnet, only to discover a 15mm cannon shell had gone straight through the engine’s cylinder head. A moment later, Captain Scratchley pulled up and they piled into his Jeep instead, Cooper clambering into the back next to Scratchley’s rear gunner, who was slumped over with a bullet in his head – he was the SAS’s only casualty. Then they were away, roaring after the rest, who were now disappearing back into the night, their departure covered by thick swirling smoke, dust and the darkness of a moonless night. ‘The scene of devastation was fantastic,’ wrote Cooper.13 Looking back he saw several aircraft burst into flames and then so did their abandoned Jeep.

They destroyed thirty-seven aircraft that night and most of them were those most precious of all German planes: the Ju52 transport, all of which were being used to airlift supplies to the front. It had been a triumph for Stirling’s men.

On 10 August 1942, Churchill had scribbled a hand-written note to General Sir Harold Alexander, the new C-in-C Middle East. His prime aim, the PM wrote, was to ‘destroy at the earliest opportunity the German–Italian Army commanded by Field Marshal Rommel together with all its supplies and establishments in Egypt and Libya.’14 Alexander felt elated. For too long he had overseen retreats – he had been the last man to leave Dunkirk, and had just returned from India where he had led British forces from Burma. Now, however, with more men and materiel arriving, he felt imbued with a sense of great confidence for the future.

Alexander had already had an extraordinary career and was unique in the British Army in having commanded men in battle at every rank apart from Field Marshal. Twice wounded in the last war, he had been repeatedly decorated and had been an acting brigade commander at just twenty-five. Then, in 1919, he had led German troops as part of the Baltic Landeswehr in the brief war against Russia – another unique distinction among his peers. In the 1930s, he also commanded a brigade of the Indian Army in Waziristan and the Northwest Frontier; during that time he had learned Urdu to add to a number of other languages, including French, Russian, Italian and German, all of which he had mastered effortlessly. Charming, witty, understated and utterly imperturbable, Alex, as he was widely known, had reputedly only ever lost his temper once and that had been during the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, when one of his men had refused to give a wounded German some water. After three years’ weeding out those not up to the task, the British Army was starting to get the right men into the right jobs.

While Alexander was a born diplomat, the same could not be said for the new Eighth Army commander, Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery. However, what ‘Monty’ lacked in people skills he made up for in no-nonsense common sense. Wounded early in the last war, he had then proved himself a superb staff officer and planner, and had demonstrated his clear-headedness and operational skills when commanding 3rd Division back in 1940. Since then, he had also emerged as a very good trainer of men. Together, Alexander and Montgomery made a rather unlikely couple, yet their experience and differing skills complemented one another perfectly. As the team to turn Allied fortunes around in North Africa, they certainly looked like a good bet.

And Alexander was quick to get started. He clearly got the impression that morale was low, that Rommel was held in far too much awe, and that in Cairo the many bars, restaurants and clubs were a distraction. Talking to a number of officers, this impression was quickly confirmed. ‘They were bewildered, frustrated and fed up,’ he noted.15 He immediately set up his new HQ on the edge of the city, at Mena, near the Pyramids. There, he and his staff could get a feel for the desert; moreover, it marked the start of the desert road to the front. He named it ‘Caledon Camp’ after his childhood home in Northern Ireland.

Montgomery, meanwhile, had appointed the Director of Military Intelligence, General Freddie de Guingand, as his new Chief of Staff, and together they quickly set up a new Tactical Headquarters in the desert – one that was cleaner, free of flies and, most importantly, right next to Coningham’s Desert Air Force headquarters. On 19 August, Alexander gave Monty his formal directive, which included an order to stand and fight where they were with no further thought of withdrawal. This was to be relayed to the men. Montgomery, who agreed entirely, began his new role with a pep talk to his senior commanders. From now on, he told them, there would be no more bellyaching – and by this he meant the questioning of orders at any point in the chain of command. Anyone who did so would be very quickly given his marching orders. ‘He gave an excellent talk on leadership and organization,’ noted Tommy Elmhirst, who, with Coningham, was there to hear Montgomery’s address.16 Elmhirst did not disagree with a word the new commander said. He thought Monty appeared to be ‘a veritable little tiger’.

Montgomery then outlined his plan. Rommel, he said, would attack in two or three weeks. ‘And we shall dig in and defeat him,’ Monty told them. ‘Then we shall do some hard training for two months. Every unit will go out of the line, one by one, to train, and on the beach if it is possible, to bathe and get clear of the flies. Then I shall attack with two corps in the line, a mobile reserve to come through the break, which we shall make in his line, and chase the remnants of his army out of Africa.’

‘It was,’ noted Elmhirst, ‘quite clear as to who was now commanding Eighth Army.’

Back in London, planning was continuing for Operation TORCH, although the precise form it would take had still not been agreed. The Combined Chiefs of Staff wanted to launch it before 10 October. By the third week in August, that was looking very tight indeed. Certainly there were all number of potential stumbling blocks to be overcome, from the continued issue of shipping availability to the far thornier matter of how the Vichy French, and even the Spanish, would react.

While such considerations were being weighed up and agonized over, a plan had been also under way to raid Dieppe. Conceived by Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Combined Operations, to whom the Commandos were attached, it was to be the biggest raid yet proposed; SLEDGEHAMMER may have been discarded, but the Dieppe Raid would, it was hoped, achieve many of the aims of the original plan. Important lessons would be learned about amphibious operations, and about the nature of German defences; and it would answer those in Britain, America and even the Soviet Union who were impatient for action. Some 6,000 troops were being sent, mostly Canadians, although 4 Commando were also included, as were a handful of the new US Rangers. Tanks were being sent across the Channel and the raid would be supported by massive air cover.

It was clearly fraught with risk and Brooke, for one, was against it. Certainly, to land so many men and machines and then get them out again was very different to the lightning cut-and-dash operations the Commandos had carried out thus far. The odds on the Dieppe Raid being a success were not high and were made worse when the original date, 4 July, had to be abandoned due to bad weather.

Among those already on board ship ready to go was Sergeant Bing Evans, one of just seven officers and eleven enlisted men of the US 1st Ranger Battalion earmarked to take part in the raid. It was Independence Day for the Americans and Evans and his fellows were off the coast of the Isle of Wight. ‘The weather was not at all decent,’ said Evans.17 Postponed initially until the 8th, their cover was blown on 7 July when four German aircraft attacked the concentrations of shipping. The crucial element of surprise had gone and so the raid was called off again. The Rangers were sent straight back to Scotland, where Evans found himself promoted to battalion sergeant-major. Although Dieppe was once again rescheduled, with fifty Rangers now involved, Evans was not to be one of them; Colonel Darby did not want to risk his most senior NCO.

That the raid still went ahead was an extraordinarily foolhardy decision. It did so, though, on 19 August and was, predictably, a fiasco. Although the 6,000 men were disembarked, they never got off the beaches, and over half the force was killed or captured, while a staggering 106 aircraft were shot down. All it had done was underline how perilously dangerous and difficult amphibious operations were and teach the planners some admittedly very important lessons.

This, however, was small comfort to Generals Eisenhower and Clark, who were still struggling to get anywhere close to an agreed plan for TORCH. They both believed there should be several simultaneous landings, both inside the Mediterranean along the Tunisian coast, and at Casablanca, in French Morocco, which was outside the Mediterranean on the Atlantic. In other words, TORCH needed to be impressively big in scope – big enough to deter a strong, hostile French and Spanish reaction. At around 3 a.m. on the morning of the 25th, however, Clark was hauled out of bed to receive a cable from General Marshall. Over in Washington, the US chiefs were starting to worry seriously. If TORCH was mounted it had to succeed, Marshall said. A landing in Tunisia was just too risky. Instead, he now suggested landings at Casablanca and Oran in French Algeria.

Back to the drawing board they went again. ‘This,’ noted Clark, ‘was the most depressing news of the summer.’18 That same night, however, Clark and Eisenhower were summoned to dinner at No. 10 with the Prime Minister. Both were in a gloomy mood as they headed over to Downing Street; they felt as though it was one step forwards and two back. Churchill, however, was in a far more chipper frame of mind, having just returned from his travels; not only had he been out to Egypt and overseen a change of command and renewed impetus, he had also flown on to Moscow to meet with Stalin. The Soviet leader was confident they could hold the Germans until the winter. He told Churchill his factories were now building 2,000 tanks a month – which was true enough. Furthermore, he professed to be ‘entirely convinced’ by the plans for TORCH – a huge personal relief to the Prime Minister.19

In this buoyant mood, Churchill insisted to Eisenhower and Clark that TORCH should go ahead, no matter the concerns. Roosevelt was of the same mind, he assured them, and Stalin was behind the plan too – the Soviet leader had been disappointed there would be no invasion of France that year, but had warmed to the opportunities of a North African invasion. ‘When Stalin asked me about crossing the Channel,’ Churchill recounted to Clark and Eisenhower, ‘I told him, “Why stick your head into the alligator’s mouth at Brest when you can go to the Mediterranean and rip his soft underbelly.20”’

Clark told him that what was needed was firm decisions – there had been so many changes, he said, they and their planning team were feeling dizzy. ‘The planners of TORCH,’ he said to Churchill, ‘are tired of piddling around.21 Every minute counts. What we need now is a green light.’

‘The Prime Minister,’ noted Clark, ‘promised action.’

For the bomb-blasted and starving citizens and servicemen on the strategically critical island of Malta, it seemed as though the Axis had held most of the aces for far too long, yet for those in the Luftwaffe and the Regia Aeronautica, it was a terrible place over which to fly, because if hordes of Spitfires didn’t intercept you then there was the intense flak over the island to contend with.

Reaching Sicily in early July was 23-year-old Tenente Francesco Cavalero, part of the 20 Gruppo Caccia Terrestre. Although he had joined the Air Force back in 1938, he had done so as a reserve officer and was still at the Air College when war broke out. By the time he joined his fighter group in 1941, they were still recovering from the mauling they had suffered during their brief foray in the Battle of Britain, and were based at Ciampino, near Rome, on defence duties.

All three squadrons in the group were short of aircraft by that time, so Cavalero had been one of those to travel separately by train, then across the Straits of Messina and on to Ponte Olivo airfield at Gela on the central south coast of Sicily. By the time he rejoined them it was almost a week after the rest of the squadron and in that time they had already lost five pilots over the island, four of whom had been killed. ‘We had a lot of losses,’ said Cavalero.22 ‘You would fly back and in the mess another of the pilots would no longer be there. He isn’t coming back.’

Within a couple of weeks, such were the losses, Cavalero had been promoted to deputy squadron commander. The greatest responsibility was trying to nurture the new arrivals; fighter training in the Regia Aeronautica focused very heavily on technical flying skills but offered almost nothing on tactical combat flying, and new pilots were simply not equipped to tussle with Spitfires or dodge intense flak. Cavalero would try to give them as much guidance as possible, warning them to turn their heads constantly, but the Axis air forces on Sicily were hamstrung by a lack of ground control and radar – and this even though Italy was the land of Marconi and despite German radar being manifestly the best in the world when the war began. Malta, on the other hand, had radar, ground control and a co-ordinated air defence system modelled on that back home in the UK.

Yet despite the recent ascendancy of the RAF on Malta, by August the island was suffering critical shortages. Its people were starving and fuel had been running desperately low. An attempt to run a convoy there in June had failed, and unless the island was urgently resupplied it would be forced to surrender; the Axis would have won after all without ever having to conduct the much-debated invasion.

Operation PEDESTAL was to be the most heavily protected convoy of the war thus far – and for just fourteen ships, including one all-important tanker. The Axis forces were fully aware of the convoy, attacking and harrying it as it passed through the Straits of Gibraltar on the night of 9/10 August and continued its slow, tortuous route through the Mediterranean. A U-boat sank the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle, although not before more Spitfires had flown off towards the island; two cruisers were sent to the bottom and a destroyer, while one by one the escorted merchantmen were picked off by a combination of Italian torpedo boats, U-boats and, as they neared the island, aircraft.

The pilots from Gela were all involved, although their contribution proved slight. Cavalero was among more than sixty Macchi 202 pilots from the entire Italian fighter unit, 51 Stormo, sent up on 13 August, by which time three of the fourteen merchant ships were nearing Malta. He was flying as wingman to the squadron commander and, as they headed out over the sea, they were soon intercepted by Malta-based Spitfires. His commander turned tightly and Cavalero followed – even more tightly, with the result that he blacked out. When he came to once more he experienced that strange phenomenon common to fighter pilots during the war: a suddenly empty sky where seemingly moments before it had been a teeming mêlée.

‘I remained in the sky over the battles for a long time,’ he said, ‘looking at the convoy on the sea under me.’23 He spotted lots of Hurricanes and Spitfires, but never had the chance to open fire – and this worried him, because he didn’t want his fellows to think he had been scared and had avoided combat.

Eventually, he realized he was running short of fuel and so landed at Pantelleria, an Italian island to the south-west of Sicily. And not before time: as he touched down, his engine cut and the propeller stopped. He had run his fuel tanks dry. When he did eventually get back to Gela, there were no recriminations. Rather, they were overjoyed to see him still alive and in one piece.

Cavalero was alive, but so too was Malta. In what was one of the most bitterly fought convoy battles ever, the combined weight of Axis air and naval forces had still proved unable to stop five merchant ships reaching the island. Furthermore, one of the five ships was the all-important tanker Ohio, which, although repeatedly hit and despite a Stuka crashing on its decks, was towed the last 50 miles by three destroyers and finally limped into Grand Harbour on 15 August. With that, Malta was saved. It meant that in the weeks to come the island could once more return to its primary role in the Mediterranean war: that of offensive base for operations against Axis shipping.

Meanwhile, in North Africa, Rommel’s concerns were mounting. He knew he had to strike Eighth Army before the end of the month and yet his supply situation had taken a downturn after the 91,000 tons received in July. Time was now running out. ‘Unless I get 2,000 cubic metres of fuel, 500 tons of ammunition by the 25th and a further 2,000 cubic metres of fuel by the 27th, and 2,000 tons of ammunition by the 30th,’ Rommel told General Josef Rintelen, the German attaché in Rome, ‘I cannot proceed.’24 The Commando Supremo duly promised more ships. Nine vessels were to leave Italy over a period of six days, starting on 28 August. But if just one of those fuel ships failed to arrive safely, his forces would be in trouble.

For Rommel, the forthcoming attack was a last throw of the dice on which the fate of North Africa would almost certainly be decided. What a dramatic turnaround it had been from the dizzy heights of capturing Tobruk just two months earlier.

On all fronts, it seemed, Germany was suddenly running out of chances.