The events of our lives happen in a sequence in time, but in their significance to ourselves they find their own order … the continuous thread of revelation.

—Eudora Welty

I glanced at my watch. I was going to be early for my three o’clock class. I stood by the window on the second floor of the education building, not far from my classroom door. I was thinking about what I was going to wear the following day for the election returns rally in Montgomery. No doubt Daddy’s grumbling attitude about his quick trip would turn to immodest smiles if he won the primaries in Maryland and Michigan the following day.

“I’m surprised to see you here!” said one of my classmates, walking toward me.

“I got here early,” I replied.

Her eyes grew wide as she lifted her hand to her mouth. “You don’t know, do you?” Her face was pale, and her voice sounded breathless as if she had been running.

An overwhelming sense of clarity seemed to surround me. I was hyperaware of the way the sunlight was coming through a window, the distant sound of a truck straining as it climbed a hill, a door slamming followed by a fever of loud voices.

“Know what?”

“Your daddy has been shot.” She began to cry.

Was it relief that I felt? That what I knew was eventually going to happen had in fact had happened? The day Mama had paced when Daddy had made his stand in the schoolhouse door was the first time I had felt fear about his safety, but that fear had been there on and off from that day until the day he was struck down.

A professor ran toward me, gathered me up, and took me to the university president’s office. Ralph Adams and his wife, Dorothy, were both stoic in the face of the news reports on the shooting.

“First Lurleen and now this,” Dorothy said as she took me in her arms. “I have no words to say.” Benita Sanders, a friend of mine, drove me back to Montgomery.

The radio blared in her car as we careened along the road, flashing the lights to make cars move over. Whipping wind from open windows helped keep nausea at bay. The street in front of the mansion was impassable. News trucks with blaring horns scattered people gathering on the sidewalks and in the street. Police cars with flashing lights blocked the mansion gates.

“This is still my house!” I shouted as I opened the passenger door and began to run. “This is still my house!”

Cornelia’s secretary was standing under the portico. She grabbed me by the shoulders. “Listen to me,” she said. “Your daddy is not dead. He is at a hospital in surgery. He is going to pull through this.”

I stared at her with blank eyes.

“There is a plane waiting at the airport. Go get what you need.”

There was little to be said as the plane took off and headed north. Daddy’s physician avoided conjecture about Daddy’s condition. “Let’s just wait until we get there before we jump to any conclusions. He is alive and in good hands. That’s all we need to know right now.”

We had learned that an Alabama state trooper on Daddy’s detail, a Secret Service agent, and a local Wallace supporter were also wounded in the attack. The troopers assigned to Daddy’s detail were like members of our family, and E. C. Dothard was no exception. His wife was on the flight with us.

As we were boarding the plane in Montgomery, Ruby roared into the parking space in front of the aircraft hangar. With an oversized purse in one hand and a small suitcase in the other, Ruby began running toward the plane.

“She is not getting on this plane,” one of Daddy’s security guards said. “How do I close this door?” Even Ruby’s screaming was no match for the mounting noise of the jet’s turbines. “God help us when she does get there,” the trooper said. Even in the midst of agony, we were briefly consumed with laughter.

It was less than six hours between the time I found out about the shooting and our arrival in Maryland. Holy Cross Hospital was bathed in garish light as we approached it by way of a residential street. The front yards of upscale houses had become haphazard parking lots for media trucks and cars. People crowded the streets. Oversized media trucks clawed through the hospital’s front lawn. A statue of the Virgin Mary, bathed in soft light, was surrounded by chaos.

Our cars were besieged when we arrived at the hospital entrance. Even the Secret Service could not keep the cameras at a distance. Cornelia was waiting for us in a private room on the surgical floor. Other than scattered bloodstains on the hem of her yellow dress, there was nothing else to suggest the horror of that day. Her composure and calm demeanor were a welcome respite.

“He is still in surgery, but he is holding his own,” she said. Just after three in the morning we were allowed to see him. The doctors were guarded in their conversations. “Thankfully your father was in excellent health. Otherwise, he would have never reached the hospital. It is too soon to give you a prognosis. We are optimistic, but he needs assurances from all of you that he is going to get through this. You need to go see him.”

The large surgical recovery room was obviously meant to accommodate more than one patient at a time, but it was completely stripped except for a single hospital bed in the middle of the floor. A battery of surgical lights suspended from the ceiling over Daddy’s bed cast beams of pure white. Humming machines with blinking red and green lights and tubes sprouting from their bottoms and sides stood haphazardly about. I shivered in the cold. Armed Secret Service agents stood in the shadows.

Daddy opened his eyes and looked at us when he heard Cornelia’s voice. “We are all here with you, George. You are going to get over this. I promised you we were going to take you home and we will,” she said.

Daddy’s right arm where he had been shot was bruised and swollen to twice its size. Bags of medicine hung on IV poles stationed on one side of the bed.

“Hey, Daddy. This is Peggy,” I said. “I came to see you as fast as I could.” I began to cry. Daddy looked my way. “Now, sweetie, don’t you cry. It’s going to be all right.”

Later, they told me the person who shot Daddy was a man named Arthur Bremer.

The following day, Daddy was removed from the critical list. He had won the Michigan and Maryland Democratic primaries. We were told that he would be a paraplegic for the rest of his life.

Daddy remained hospitalized at Holy Cross Hospital for fifty-three days. Thousands of letters poured in to the hospital as well as the governor’s office. Even with volunteers and additional staff, the volume was overwhelming. Over twenty thousand responses were sent on directly to his office for reply, thousands more diverted to two colleges for handling, while thousands more were never acknowledged at all.

Some of the letters suggested miracle cures, special diets, medical devices, and the laying on of hands to heal him from his paralysis. They were reminiscent of many of the letters that Mama received in the midst of her struggle with cancer. It was inspiring to know that so many people cared.

On July 7 a military hospital plane touched down at the Montgomery airport. A large crowd cheered and cried as they saw Daddy in a wheelchair for the first time. Although his voice was weak, the well-wishers buoyed his spirits. He had come to reclaim the governor’s office from the acting governor, Lt. Gov. Jere Beasley, amid the rumors of a Beasley power grab that were being fostered by Wallace insiders who were buried deep in the piggy banks of state service contracts: food providers for state cafeterias, road-building and printing contractors, administrators of the state’s health insurance and pension funds, state boards, bridge construction and maintenance companies, university and community college services, and more.

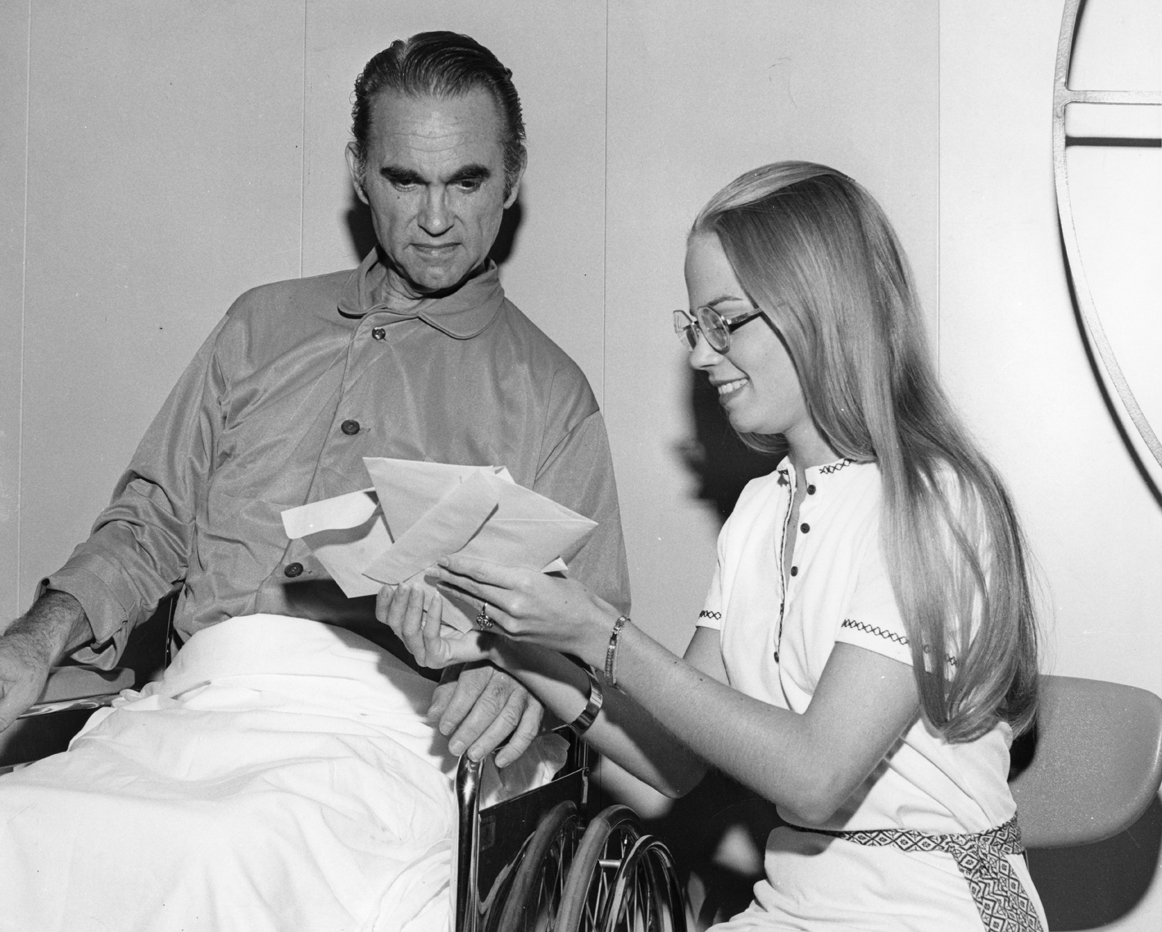

Me and Daddy reading “get well” letters at Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Maryland, 1972.

The real motivation behind Beasley’s ousting may have been his penchant for honesty. Sighs of relief from the Wallace insiders were heard all across the state when local television stations announced, “And now we are going live to Montgomery where an Air Force C-147 hospital plane carrying Governor George Wallace and his family has just landed.” In less than an hour, the hospital plane took off heading south to Miami and the Democratic National Convention. Daddy was the governor of Alabama again.

Daddy spoke at the convention on the evening of July 11. His bodyguards lifted Daddy in his wheelchair to the stage. The Wallace delegates along with the majority of others stood and applauded. Although he was obviously in pain, his voice was strong as he spoke about returning to the values of the average working-class man and woman.

The following day, Daddy was nominated for president. He received 23.5 percent of the convention vote and earned 382 delegates, putting him third in the final count. Some said it was the height of his political career. As he was wheeled off the podium, no one could have imagined Daddy would run again for president in 1976 and serve two more terms as governor of Alabama; most people assumed George Wallace’s political career was over.

The day after his appearance at the convention, Daddy was flown to the hospital in Birmingham for an emergency surgical procedure to treat internal infections caused by perforations of his intestines when he was shot.

After Daddy recovered from his surgeries, he was admitted to the Spain Rehabilitation Center at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. It was time for him to accept the new reality of the rest of his life as a paraplegic. His battle with depression and a growing dependency on pain medications soon overwhelmed him. While he was at Spain, he met a young woman who was a quadriplegic as a result of a motorcycle accident. The driver of the motorcycle, her fiancé, was not injured. He, along with her parents, had long since abandoned her. She was alone. Every day, Daddy visited her. Following her release, he called her often. Their friendship led him to speak frequently to others with paralysis and to promote funding for research.

Daddy leaving Spain Rehab in Birmingham, Alabama, August 1972.

In late May, after the assassination attempt, I returned to Montgomery to try to salvage what I could of my spring quarter classes at Troy. With an uncertain future ahead, it became obvious to me that a college degree was more important than ever. At least by the spring of 1973, I would have a teaching degree in hand. The prospect of being on my own became real; Mama and Mamaw were both gone. Mamaw had died of cancer on January 2, 1971. Mr. Henry, heartbroken yet again, moved to a small house in Tuscaloosa to live with his sister. There was no more broken road to go to.

Before Daddy left the rehabilitation center to return to Montgomery, the mansion went through a transformation. Its staircases, narrow halls, bathrooms with no showers, open second-floor galleries, and exterior steps to every entryway would make it difficult if not impossible for a paraplegic to live there. The upstairs sitting room and the connecting hallways on both sides that were open for view from the first-floor entryway were walled up. Bulletproof glass covered all the second-floor windows.

Halls and interior doors were widened. The master bedroom closet fell victim to a doorway cut into what had been my bedroom when we first moved to the mansion. It would serve as Daddy’s therapy room. What had been my bathroom was gutted to install fixtures to accommodate the needs of who my daddy would be when he came home—a man paralyzed for the rest of his life.

An elevator, installed in a newly constructed tower in the rear wall of the mansion, was the only means to carry Daddy upstairs. Exterior ramps appeared at designated entryways, and the family dining room furniture was replaced. The mansion was ready for his return.

When Daddy came home, he felt the absence of the constant coming and goings of the therapists and doctors who had attended him at the hospitals. His physical and mental condition worsened. Although Daddy’s doctors warned him of the dangers of drug dependency, his demands became more frequent and his personality more sinister.

We were soon living in the midst of what felt like a Southern gothic nightmare. Daddy’s angry outbursts increased and were often directed at us. There was no give and take in his conversations with me, no interest in my life and what I was doing apart from him. He demanded sympathy.

For the first time in his life, Daddy had no choice but to live with us rather than around us. Throughout his life, Daddy’s passion had been people, the kind that sat around the town square, gathered in small-town restaurants, or worked in the fields. His style of politics was all about racing to the next hand to greet, climbing up on the front porches of wood-framed houses, heel-and-toe walking along sidewalks, and last-minute jaunts up just one last staircase to shake a fella’s hand. Daddy’s perpetual motion defined him, energized him, fed his overwhelming need to be present in the moment. Everyday worries could not catch up as long as he was moving. The legs that carried him were akin to an artist’s hands. Lose them and the magic was gone. He would have to learn another way.

As Daddy struggled with the challenges of his paralysis, his physical pain, and the new realities of his future, his inattention to the politics of the governor’s office gave rise to warring factions within his inner circle. People were afraid. The Wallace brand had been supporting their families for more than a decade, and the mere thought of its coming to an end was unspeakable. No one had ever thought about a contingency plan in the event there were no more Wallaces. While Mama’s death may have caused a significant setback, an unexpected and abrupt George Wallace exit from Alabama politics would have backlogged bankruptcy courts for years. State employees would have jobs no matter the outcome of Daddy’s medical challenges. But the two c’s of the Wallace brand, contracts and campaigns, were uncertain.

“The suggestions of the press that I am unable to fulfill my duties as governor are just another attempt to undermine the wishes of the people of Alabama,” Daddy said as media outlets began to question his ability to serve out his term. Rumors of his depression and drug addiction spread. The Montgomery Advertiser called on Daddy to immediately retire. According to some members of the press, the governor’s office was besieged by power brokers and Governor Wallace was in no shape, physically or mentally, to carry on. While many agreed, Wallace supporters rose up in righteous indignation and attacked both the article itself and its author.

The challenge to Daddy’s authority was in some way more therapeutic than the hours of physical therapy he endured. Perhaps he remembered what his father said to him when, as a teenage boxer, Daddy would find himself lying on his back in the boxing ring: “Don’t you just lay there, shake it off, get up and knock the little bastard’s head off.”

Daddy’s ultimate recovery was a testament to his determination and courage. His coming to terms with his paralysis freed him from despair. But most important, his living with me rather than just around me changed my life. He was always there—he wasn’t able to dash off.

As we adjusted to our new reality, Cornelia took it upon herself to play matchmaker. In her view, now that I was at the age of twenty-two, it was time for me to get serious about finding a husband. Her list of eligible prospects was a veritable who’s who of unmarried Alabama notables. When she found out that the Alabama Department of Tourism was planning an all-expenses-paid (minus spending money), ten-day excursion to Europe to promote Alabama tourism, she signed me up, perhaps hoping I would meet a prince. Daddy gave me a bon voyage hug and a hundred dollars. “Don’t tell your daddy,” Cornelia said as she slipped me a cash-filled envelope.

The mansion was decorated for Christmas when I returned. December 15 was the only occasion in my life when I had two dates on the same night. While Cornelia’s quest for the perfect husband was ongoing, my first encounter of the evening was with someone I had never met and was arranged by my friend Benita, who had driven me from Troy to Montgomery on the day Daddy was wounded in Maryland, and her friend Carol Wells from Greenville.

“This is going to have to be no more than a meet and greet at your house,” I complained over the phone. “I already have a date. The only reason I am doing this is for you. Now tell me his name again and where is he from?”

“His name is Mark Kennedy, and he’s from Greenville.”

“Never heard of him.”

I walked up onto her front porch and rang the doorbell. I forced a smile as the door opened.

My future husband stood up and shook my hand.

During our brief conversation, there was no mention of politics or inquiries about my family. It was about me. There was no talk of connections, no “all of my family loves Governor Wallace” moments. I became uneasy. I had never lived outside the context of who my father and mother were and what they had done. Being in the center of a conversation was nothing new to me, but standing alone in the center of a conversation was.

After a pleasant but very ordinary chat, I offered my “Nice to meet you” and left. I gave Mark my phone number but was not sure he would call. “Nice enough, even looks a little bit like Daddy, meeting him made my friends happy, not a total waste of time,” I said to myself.

“Sorry I’m late,” I said as I sat down on the barstool next to my date for the evening. “I had to do a favor for a friend.”

“No problem,” he replied. “You want a Coke or something stronger?”