By comparison with Hiroshima, the explosive detonations of Vesuvius or Krakatau were relatively gentle upheavals, long and drawn out, releasing their energy over many, many seconds. Because the core of the atomic bomb was much more compact, its energy was released in one small part of a lightning bolt’s life span, within a cauldron measured in cubic centimeters of metal, instead of across several dozen cubic kilometers of explosive, gas-saturated magma.

And yet, for all its fury, the Hiroshima bomb had not lived up to its designers’ specifications. Though the Truman Administration and the media would officially list it together with the first atomic test in the New Mexico desert, and with the Nagasaki bomb, in the 20–30 kiloton range, it was in fact a 10–12.5 kiloton “disappointment.” The design would never be used again. Some engineers and scientists would even go so far as to call it a “dud,” but humanity would be forever haunted by the power of a bomb that merely “fizzled,” like a damp firecracker.1

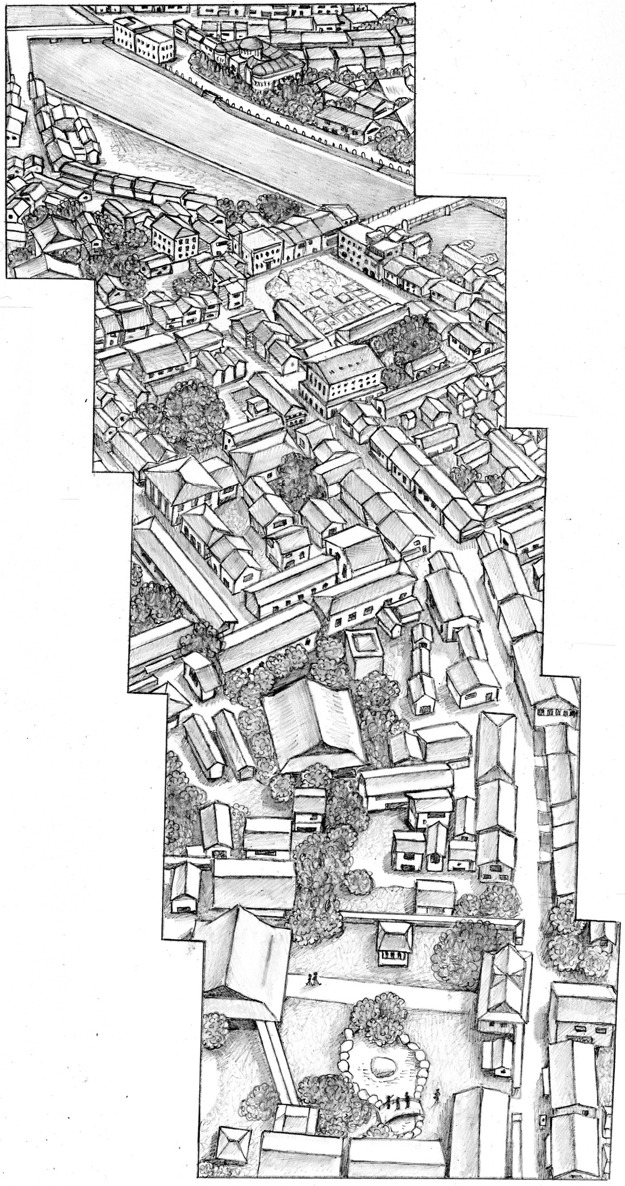

Before and after views of Hiroshima [this page and facing page], looking from a circular fishpond (approximately 500 meters from the hypocenter), toward the T-Bridge and the Dome. Setsuko Hirata was located in a house in the vicinity of the pond. [Illustrations: Patricia Wynne]

At a quarter-past eight, near the center of a pomegranate’s volume of compressing uranium, the vast majority of the bomb’s energy had radiated from a spark scarcely wider than the tip of young Setsuko Hirata’s index finger. By the time the golden white plasma sphere had spread eighty meters wide—still within only one small part of a lightning bolt’s life span—the spark had generated a short-lived but very intense magnetic field. Where the bomb had been, the metal rod and tamper system that ran down its center from nose to fin produced a cluster of dense metallic nuclei—stripped of their electrons, positively charged, and magnetically confined within forces that were trying to blow them apart at nearly the speed of light. The minds that conceived the bomb had accidently created, for an instant, a predecessor to Brookhaven National Laboratory’s relativistic heavy-ion collider. The bomb was an atomic accelerator whose magnetic shotgun barrels were aimed straight up and straight down. One stream of iron and tungsten nuclei went to the stars at up to 90 percent light speed, passing the orbit of the moon about a second and a half later. The other stream followed magnetic field lines to the ground. Both streams produced “strays” that arched along field lines almost twelve miles away, brushing through the planes that had delivered the bomb.

Setsuko Hirata was seated in her living room, slightly to the south and almost directly beneath the magnetic shotgun. Fast neutrons and heavy ions came down through tiles and roof beams and either stopped inside her body or kept going until stopped by the first hundred meters of sand and bedrock. Neutrinos also descended through the roof. Born of the so-called weak force, their interactions with the world were so weak as to be utterly ghostly. Almost every one of them that encountered Setsuko continued through the floor without noticing her, then traveled with the same quantum indifference through the Earth itself. The very same neutrinos that passed through Setsuko, drawing a straight line between her and the bomb, and through nearly 5,000 miles of rock, emerged through the floor of the southern Indian Ocean and sprayed up toward interstellar space. Setsuko’s neutrino stream would still be traveling beyond the stars of Centaurus, beyond the far rim of the galaxy itself—still telling her story (as it were), long after the tallest skyscrapers and the Pyramids had turned to lime.

When Setsuko’s neutrino spray erupted unseen, near the French islands of Amsterdam and St. Paul, not quite 22 milliseconds after detonation, she was still alive. Ceramic roof tiles, three meters above her head, were just then beginning to catch the infra-red maximum from the flash—which peaked 150 milliseconds after the first atoms of uranium-235 began to come apart. The tiles threw a small fraction of the rays back into the sky, but in the end, they provided Setsuko with barely more protection than the silk nightgown her beloved Kenshi had bought her only a few days earlier during their honeymoon at the Gardens of Miyajima.

Overhead, along the lower hemisphere of the blue-to-gold to blue-again globe that expanded from the place where the bomb had been, droplets of moisture had dissolved into a scatter of electron-stripped hydrogen and oxygen nuclei. A very small number of those hydrogen nuclei were smashed together and fused, and collectively an amount of mass not quite equal to a fleck of the finest-grained beach sand disappeared from the universe, adding a little kick of fusion to the fission power that burst down toward Setsuko. The instantaneous transformation of matter into energy produced a light so intense that if Setsuko were looking straight up she would have seen the hemisphere shining through the single layer of roof tiles and wooden planks as if it were an electric torch shining through the bones of her fingers in a darkened room. And within those first two-tenths of a second, she might have had time enough to become aware of an electronic buzzing in her ears, and a tingling sensation throughout her bones, and a feeling that she was being lifted out of her chair, or pressed into it more firmly, or both at the same instant—and the growing sphere in the sky . . . she might even have had time enough to perceive, if not actually watch, its expanding dimensions.

Setsuko’s husband, Kenshi, had been working as an accountant at the Mitsubishi Weapons Plant, slightly more than four kilometers away, when through a window came the most beautiful golden lightning flash he had ever seen, or imagined he would ever see. Simultaneously there was a strange buzzing in his ears, a sizzling sound, and a woman’s voice crying out in his brain. He would suppose years later that maybe it was his grandmother’s spirit—or more likely Setsuko’s. The voice cried, “Get under cover!”

With all the speed of instinctive reflex, he dropped the papers he was carrying, dove to the floor, and buried his face in his arms. But three long seconds later when the expected shockwave had not arrived, he was left in adrenalized overdrive—with time to pray.

Outside his Mitsubishi office, in utter silence, a giant red flower billowed over the city, rising on a stem of yellow-white dust.

Kenshi’s prayers seemed to have been answered—yet again. He had walked away from the fire-bombing of Kobe without a single blister or bruise, initially thinking himself a bit unlucky because he should never have been there in the first place; and Kenshi would never have been there, had he not finished his work in Osaka a day early and departed for Kobe ahead of schedule. Two nights after surviving Kobe, he learned that Osaka, too, had been heavily bombed. Indeed the very same hotel in which he should have been sleeping took a direct hit, with no survivors. At Hiroshima, Kenshi owed his survival to an instinct to obey an inner voice, and to the fact that the bomb had disappointed its creators, yielding a blast wave that was all but fractionally spent by the time it reached him. Kenshi’s next instinct did not serve him so well as his obedience to the voice. When he dropped to the floor, his initial impression was that a number of huge incendiary bombs were exploding right on top of the building and that he would be cremated even before he could finish the first lines of a prayer. But nearly five full seconds followed the flash, and the light itself began to fade without a hint of concussion—The bombs have not struck the building—

The multiple bombing-raid escapee raised his head to see what was happening around him. A young woman nearby had crept to a window and peeked outside. Whatever she saw in the direction of the city, Kenshi would never know. She stood up, uttered something guttural and incomprehensible, and then the blast wave—lagging far behind the bomb’s light waves—caught up with her. By the time the windowpanes traveled a half-meter, they had separated completely from their protective cross-hatched net of air-raid tape, emerging as thousands of tiny shards. Like the individual pellets of a shotgun blast, each shard had been accelerated to more than half the speed of sound. The girl at the window took at least a quarter-kilogram of glass in her face and her chest before the wind jetted her toward the far wall.

Kenshi did not see where she eventually landed. Simultaneous with the window blast, the very floor of the building had come off its foundation and bucked him more than a half-meter into the air. He landed on his back, and when he stood up he discovered to his relief that he was completely unharmed, then discovered, to his horror, that he was the only one so spared. All of his fellow workers—all of them—looked as if they had crawled out of a blood pool.

We must have taken a direct hit after all, Kenshi guessed. He did not realize the full magnitude of the attack until he stepped outside. In the distance, toward home, the head of the flower was no longer silent. It had been rumbling up there in the heavens for more than a minute, at least seven or ten kilometers high now, and it had dulled from brilliant red to dirty brown, almost to black. As he watched, the flower broke free from its stem and a smaller black bud bloomed in its place. It was, a fellow survivor would recall, like a decapitated dragon growing a new head.

A whisper escaped Kenshi’s lips: “Setsuko . . .”2

Being immersed in death, Father M. (“Mattias”) would recall, could be as bad as being counted among the dead. At the presbytery of the only Catholic church in the city, 1.3 kilometers east of the hypocenter, he, Father Hubert Cieslik, and Father Lassalle had heard two planes moving overhead, revving their engines to full throttle and diving, as if trying to escape something. Overlooking a garden patio, the young Novitist who would become Fr. Mattias saw two parachutes drifting overhead and the otherwise empty sky suddenly strobed blue, then yellow—and then the ceiling dropped.

Mattias did not know what happened after that. His memory seemed to be recording only disjointed pieces. His first clear recollection was of walking toward the river; but time was playing tricks on him. All the usual reference points—the church and every other landmark—were lost to him. Some time ago—

A minute? An hour?—he had joined hundreds of other dazed, half-naked people and become one of the ant-walkers. The skin of the man in front of him flapped loosely from his back, like pieces of a tattered shirt; and all of the flesh on his forearm had been pulled off. The priest related twenty-nine years later how he followed the walking corpse aimlessly until it—and the scarecrow in front of it—bumped headlong into the frame of a charred and smoldering streetcar. When Mattias peered inside, he saw that the passengers’ clothing and skin had been stripped off. Only one of them stirred: an unborn baby still struggling inside its dead mother.

He stumbled away, leaving the man who had led him to the streetcar gaping and swallowing on the ground, like a fish on dry land. Mattias did not know where he was going, but more than a dozen people fell in line behind him anyway, and began to follow.3

Another who walked in a state of shock was, compared to the rest of the population, only mildly burned. He was a fourteen-year-old named Akihiro Takahashi. The boy followed streetcar tracks past wrecked, corpse-filled trolleys, until he heard a friend calling his name. Then he veered off in the direction of his friend, and a new ant trail began to form behind them.

The friend whose call the boy had followed was already so severely penetrated by radiation that his teeth would soon be falling out. Akihiro would hear later that, “Before he died, his belly turned purple and he vomited up a continuous stream of some blue-gray substance.” The fourteen-year-old encountered a woman with an eyeball dangling on her cheek, and a horse with its skin blasted away to expose raw, blood-drenched muscle, lying dead with its head in a concrete, water-filled cistern.

Coming out of his daze, the boy became increasingly aware of people following him; but most of them did not look like people anymore and they were pressing uncomfortably close. How is this possible on Earth? he thought, quickening his pace toward the nearest river, trying to leave the ant-walkers behind. Ahead, the smoke and the dust parted, as if to taunt him with the realization that there was no escaping what he had walked away from at the blackened trolley cars. Next to a mother whose body had been completely de-gloved lay a screaming infant, its entire skin surface either converted to or covered by a thin veneer of charcoal. This was not the last or even the worst horror Akihiro passed in his search for home. There were others for which descriptive words had not yet been invented. Only an hour earlier, it seemed, Akihiro had been standing in a sunny schoolyard watching a B-29 making a strange acrobatic swerve miles overhead, as if it were about to crash. And then, at a radius of 1.4 kilometers from the target area, blistering heat consumed the school and a crypt-like darkness descended. For the fourteen-year-old, the margin between life and death was determined by a shadow-casting tree that had allowed an arm to be seared and air-blasted but had otherwise shielded his body from the flash.

More than twenty-five years later, the boy would be seated at a bus station in Washington, D.C., with an American chaperone and Paul Tibbets, the pilot of the plane that dropped the bomb; and Akihiro would listen to another survivor telling Tibbets how from the presbytery he had heard the plane’s engines straining to get away from the bomb on this sunny August morning. Akihiro sat in silence for a very long time, knowing about Tibbets’s reputation—about a willingness to reenact the bombing at air shows, and even to joke about his role in history by eating from birthday cakes shaped like mushroom clouds. Nervously, Akihiro told Tibbets that though it was amazing to wonder how a man could be close enough to have heard Enola Gay’s engines and to have survived, he had actually spotted Tibbets’s airplane. And Tibbets remarked, “Yes, I could see all of Hiroshima below me.”

Akihiro pushed his badly healed and partly de-gloved hand toward Tibbets, and the pilot asked, “Is this the effect of the A-bomb?”

“Yes,” Akihiro replied, and it seemed to him that Tibbets looked surprised and shocked, but he gently took hold of Akihiro’s hand, and the survivor said, “We must overcome the pain, sorrow, and hatred of the past—and [we must] work together to make sure that people never experience this again.”

“I understand,” Tibbets said, adding the inevitable but: “I would have to do the same thing, under the same circumstances; because once war breaks out, soldiers can do nothing but follow orders.” He closed both of his hands around Akihiro’s scars and said, unexpectedly and with clear sincerity, “We should never let war happen again.”

Akihiro said later to one of the other survivors that he believed Tibbets felt some pain and remorse in his heart. But the friend replied, “I doubt it.”

Whether his perception of Tibbets was real or not, Akihiro came away from the meeting with a sense of inner peace. Later, he wrote, “Among humankind’s abilities, it is said imagination is the weakest and forgetfulness the strongest. We cannot by any means, however, forget Hiroshima, and we cannot lose the ability to abolish war. Hiroshima is not just a historical fact. It is a warning and a lesson for the future.”

For Akihiro Takahashi, there was resolution and a hope for the future. For the priest who had followed the same sets of tracks past incinerated rail cars, there was neither resolution nor hope, forever. Till his last breath, he would remain a man trapped by his past, in August 1945.4

Far beyond the streetcar and Akihiro’s ant trail, the corner wall of what appeared to have been a brick apartment house—all that remained of the building—had towered three stories above Father Mattias’s head. Three children clung to the top of the tower, screaming. They were naked, and it registered somewhere in the back of the young man’s mind that one of them seemed to be bleeding from his entire body.

At first grateful that he had been spared, once the unreality of the walking numb-state succumbed to clarities born of atrocity, he began slowly, surely to blame himself for having survived. As he reached the river and the first rescue boats began plucking corpses out of the water and as he waded into the water himself and watched a woman carrying her child toward him—pleading with the infant to open his eyes—barely noticing that as she stepped into the water her own skin and musculature began to fall away from the bones, the merciful numb-state began to crack. And he was touched by merciless guilt.

That’s when he began thinking, truly thinking for the first time, about the three children he had seen at the brick tower. There were no familiar landmarks pointing the way back, and the fire worms had begun gathering themselves together into roving walls of flame. And he would wonder, every day for the rest of his life, whatever happened to the children at the tower. Each night, they would become the very last thing he thought about before he fell asleep. And he would dream about them. And they would be the first image that came to mind when he awoke.5

As Kenshi made his way toward the center of the city in search of his wife, the streets and fields sprouted what seemed to be thousands of tiny flickering lamps. He could not determine what the lamps might actually be. Neither could any of the scientists who would hear of this later. Each jet of flame was about the size and shape of a doughnut. Kenshi knew that he could easily have extinguished any “ground candles” in his path merely by stepping on them; but he was “spooked” by an instinctive sense that it might somehow be dangerous to touch the fiery doughnuts, so he stepped around them instead.6 He thought of Setsuko. He passed men and women whose backs had been seared by the flash, but it was not the flash-burns that caught his attention and stuck in his memory. The people appeared to be growing strange vegetation out of their roasted flesh. It occurred to Kenshi only much later that thousands of glass slivers must have been pulled from the windows of every building and driven through the air like spear points. He thought of Setsuko. Limping, the young accountant circumnavigated a giant column of flame in which steel beams could be seen melting. He thought of Setsuko. Nearer the hypocenter, not very far from the city’s Municipal Office, he passed over a warm road surface upon which a great fire must have risen, then inexplicably died. All of the people simply disappeared here, and all of the wooden houses, on either side of the road, were reduced to grayish-white ash. He thought of Setsuko. The main street leading toward home and the famous “T”-shaped bridge seemed more like a field than a road. In the middle of the field, he found two blackened streetcars. Their ceilings and windows had vanished, and they were filled with lumps of charcoal that turned out to be passengers carbonized in their seats. The trolleys had apparently stopped on either side of the street to pick up more passengers, and two people were about to ascend the steps of one vehicle when the heat descended, and caught them, and converted them into bales of coal with shirt buttons and teeth. In every direction, Kenshi saw pieces of people, and horses, and oxen, looking like charcoal. He thought of Setsuko, now blaming himself for their ill-omened honeymoon excursion, nearly two weeks earlier, to the Shrine Island of Miyajima.

There was a strange taboo in connection with the Miyajima Shrine. It had been dedicated to a goddess who was believed by the older generations to become jealous if a newly married husband and wife climbed the sacred steps together. If the taboo was violated, the old people said, the wife would shortly die. But Kenshi’s friend, a local innkeeper who had arranged honeymoon lodgings for them near the island’s gardens, had scoffed at this and said it was pure superstition. Since they had come all the way to Miyajima together, he advised, surely they should go at once to the famous shrine. So they did. And now, during the journey from his office into the heart of Ground Zero, Kenshi repented of it many times.7

Yosaku Mikami had missed his streetcar by only a few seconds, so he had to wait for another one, and he was therefore running nearly a quarter-hour behind his normal schedule when the next streetcar carried him by chance under the protection of a shadow-shielding effect from the train office and other structures near the Miyuki Bridge, rendering him one of the few surviving firefighters in all of Hiroshima.

Many of the buildings around Yosaku were made primarily out of wood. At a radius of 1.9 kilometers, the shockwaves pulled them apart; but they held together just long enough to keep the streetcar hidden in their shadows, as if within the protection of a valley or tunnel, through the duration of what Yosaku recalled as a blue flash. As the flash began to fade, and as the buildings flew apart, a blast of black smoke filled the rail car, carrying with it an odor that instantly pervaded the city, across a diameter of nearly three miles and on all sides of the hypocenter. It was partly the scent of flash-burned wood and leaves, partly an acrid metallic smell, and partly a dreadful stench already familiar to most firefighters. Yosaku and the minority of firemen near central Hiroshima who were still able to move and breathe after the first five seconds understood at once exactly what they were inhaling. The odor that human flesh emitted when it was burned happened to be quite similar to the smell of squid when it was grilled over hot coals—and so, as Yosaku ran toward the place where his fire house had been, he was breathing in the smoke of people, tens of thousands of people.

During what seemed to be several minutes after the blue flash (though in an adrenalized state of mind it became difficult to determine spans of time), Yosaku saw a fire truck maneuvering around piles of rubble toward one of the main roads. Uninjured, he jumped aboard and joined colleagues who drove him to a main fire station where, in a manner consistent with the tradition of firemen spontaneously migrating from outlying regions into a destroyed region, they found a half dozen other firefighters already gathered. There did not seem to be much that they could accomplish, with only one truck known to be operating and all of the city’s water pressure knocked out. They were located near the two-kilometer radius, and anything much nearer the center of the city appeared to be enveloped in a constantly expanding maelstrom of smoke and chaos. There was no point in moving nearer the center. More lives could be saved by finding survivors who were still able to walk and to lead them farther away.

In a house at Yosaku’s radius from the hypocenter, the piano that seventeen-year-old Misako’s father bought for her in 1932 would ultimately be saved for future generations by the child of another Hiroshima firefighter, named Mitsunori. Young Misako’s piano had been shrapnel-studded along one side by more than a hundred pieces of speed-slung glass. And yet what historians would later call “the hibakusha piano” was, except for the embedded glass, safely cocooned in an air pocket, while the rest of the house imploded. Misako, who had played the instrument from the age of four, survived by having been sent away from central Hiroshima, to a munitions factory work detail. She never did play the instrument again, after that day. For a long time, a part of her believed that no one should ever play it again.

Throughout the coming decades, the black stand-up piano would set out on a convergent course with the family of a Hiroshima fireman who had been located within less than half of Firefighter Yosaku’s radius.

Much like the piano, Firefighter Mitsunori was shock-cocooned, while most of the building in which he had been standing disappeared around him. In years to come, Mitsunori would tell his story of the shock-cocoon and fire worms to his yet-to-be-born son, Yagawa—who did not arrive until seven years after the war.

Yagawa would always remember the expressions of bitterness and pain—and even remorse that creased his father’s face when he spoke of having emerged from a steel and concrete stairwell into a fire station that no longer existed, and how he beheld an instantly changed landscape whose sky was becoming full of worms. The story seemed unreal and even irrelevant to the boy, like something that must have occurred in a distant country, and long ago. After he came of age during Japan’s economic surge of the 1960s, Mitsunori’s son would look back from the second decade of the next century and say, “My youth, compared to my father’s, was extremely fortunate. That’s why I did not understand. I realized later that I took peace for granted—just like the inexhaustible supply of electricity, and water, and never having experienced anything like the war-time rationing of food.”

The younger Mitsunori grew up to become a musician and restorer of old instruments; but the son of a shock-cocooned fireman came to his own sense of understanding and remorse after Misako, who had followed through with her vow never to hear the piano played again after Hiroshima, contacted him in her seventy-eighth year, pleading with him to take care of her shock-cocooned relic.

“I wonder what will happen to my piano when something happens to me,” she said, hoping that the memory of its place in history would not die with her. “That has been my concern,” she emphasized, before passing the instrument down to the fireman’s son. “I fear that it could be thrown away as just another old piano.”

As he repaired two deteriorating strings and re-tuned them, Yagawa Mitsunori came to wish that he had listened more closely to his father’s story, had tried to understand while he was still alive.

During his long and careful repair, Yagawa was surprised to discover that the piano, well-kept in a ventilated room but silenced by its owner since 1945, could produce so deep and powerful a sound. “A miracle piano,” he called it. “Listening to its sound, I thought it was a piano that was inevitably left for a purpose.”

In 2010, he would bring the piano to Lower Manhattan, partly to honor the 343 firefighters who had died nearby (in the World Trade Center), and partly to provide background music for a floating lantern ceremony. Trains of flickering paper lanterns on the Hudson, most of them inscribed with personal messages to the future, were part of a Buddhist tradition imported to New York by a handful of monks on September 11, 2002. By 2010, the 9/11 floating lantern ceremony was attended by uncounted hundreds of people. On a small plywood outdoor stage, the hibakusha piano’s tones became the backdrop against which a rabbi, an imam, and a Catholic priest spoke together about hope, while the Sikhs brought food for everyone in attendance.

“Before I worked on this piano,” Yagawa would tell one of the first 9/11 families to attend the lantern ceremony, “I had no interest in peace movements. I did not think I would change this much. Music has nothing to do with religion, ideology, or national borders. I hope that through this piano, many people will begin to think.” Yagawa really did not hold onto any great hope that music from a glass-scarred, slightly radioactive Hiroshima piano would bring enough people to believe that the concept of “limited nuclear war” could only lead to the full-scale death of civilization and must be put aside; but impossible hurdles would not discourage him from trying.

While repairing the piano, Firefighter Mitsunori’s son thought often about him. The musician could not help feeling that the instrument had come to his studio with a piece of his father’s soul in its deep tones, along with a piece of the old woman’s soul.

On that sunny 1945 morning transformed into a sky full of worms, Firefighter Mitsunori climbed out of a stairwell only 800 meters from the hypocenter. Although a thick shell of steel and concrete had shadow-shielded him from the flash, had absorbed most of the outdoor gamma-shine and neutron spray that reached twice the usual lethal human dose, and had shock-cocooned him from the blast, the firefighter was all but instantly buried alive. He was obliged to worm his way up through brick and concrete rubble, slicked with his own blood and trying his best not to further damage an arm he already knew to be fractured.

What no one understood in 1945 was how poorly evolved human minds were for coping with a catastrophe that manifested in a split second over multiple square miles.

For Dr. Hachiya, for the schoolboy who ran away from the hands clutching at his feet, for the priest-in-training who walked in a daze past three children trapped and bleeding, and for Firefighter Mitsunori, the conscious part of human thought had retreated in a manner only rarely seen during the gradually unfolding approach of a typhoon, or during a fire that begins in one home and spreads over the course of several minutes to its neighbors. Mitsunori’s catastrophe was born of micro-time frames that belonged to the cosmos. By the fireman’s own account, the conscious part of “self” had moved from the driver’s seat to the passenger seat of his brain, ceding control to subconscious, instinctive thought—which acted by snatching up and analyzing every sight and sound, operating so frantically in its search for a means of self-preservation that the reduced-to-observer-status forebrain usually later recalled time itself seeming to have been distorted, along with a sense of somehow standing partly outside of the event, watching it happen to someone else.

Mitsunori could vaguely recall for his son how he became trapped beneath the rubble—and how, if not for at least two men who heard his calls and dug him out of the stairwell, and pulled him to the surface, he probably would not have survived at all. His rescuers could not have known that, having been exposed to the bomb only 800 meters from its hypocenter, and outside of Mitsunori’s steel and concrete shell, they probably had only two or three days left to live. The firefighter also recalled, with deep remorse, having clasped his hands together as if in prayer and bowed like an automaton before walking away, still machine-like, from the brick pile of the fire station. Behind Mitsunori were the men who had rescued him, and beneath them were people—some of them undoubtedly fellow firefighters—crying out from under the bricks.

No one else was ever known to have survived in a fire station at the Mitsunori radius. Only photographs of the aftermath would live on. At 800 meters, one photographic set (which was eventually widely published) showed fire trucks half buried in broken concrete and bricks. The positions of the trucks indicated where the station’s engine bay had been, though so little else remained that the elder Mitsunori could never be sure that it was the firehouse from which he had escaped. Only the trucks and the building’s foundation lines were recognizable, after the firestorm swept through. The foundation lines were no longer straight. Before the storm carbonized him, one firefighter had either been scorched to death by the flash or shot through by flying debris, behind the wheel of the most intact of the station’s trucks. The man looked as if he must have been standing near the truck when the flash came, and had jumped into the cab and was about to start the engine so he could fight a fire—but then, of course, he could not.8

The streets of Hiroshima were full of intriguing, seemingly impossible juxtapositions between the utterly destroyed and the miraculously unharmed. The roof tiles of Kenshi’s home had boiled on one side and were cracked into thousands of tiny chips, and evidently the entire structure was simultaneously roasted and pounded nearly a half-meter into the earth. A few doors away, evidence of a gigantic shock bubble, in which the very atmosphere had recoiled at supersonic speed from the center of the explosion, could be seen in the evidence of the bubble’s immediate aftereffect—the “vacuum effect” that had developed behind an outracing shockwave, pulling everything back again toward the center, toward the actual formation point of the mushroom cloud, almost directly overhead. The force of the imploding shock bubble had also pulled air-filled storm sewers up through the pavement. These manifestations only hinted at the forces unleashed when the low-density bubble, its walls shining with the power of plasma and super-compressed air, had spread and cooled to a point at which the press inward by the surrounding atmosphere started to become stronger than the heat and shock pushing away from the uranium storm. At this point, the shock bubble was only about 250 milliseconds old—just a quarter-second past Moment Zero and 400 meters in radius. When the bubble collapsed, less than two-tenths of a second later and nearly twenty blocks wide, the updraft experienced directly below, in Kenshi’s neighborhood, was amplified by the almost simultaneous rise of the retreating plasma, which behaved somewhat like a superheated hot-air balloon. As it rose and lost power, it had cooled from a fireball to an ominous black flower head, and had begun to shed debris the way a flower sheds pollen. Bicycles, bits of sidewalk, planks of wood, even half of a grand piano, fell out of the cloud, more than 800 meters away from the hypocenter.

And yet, amid all this havoc, pieces of bone china and jars of jellied fruit lay unbroken upon the ground. Kenshi discovered that trees, although dry roasted and stripped of their leaves, were still standing upright and unbroken in a 30-meter-wide area just outside of his immediate neighborhood. A three-story house, too, appeared to have survived among the stands of upright trees, suffering only a severe shaking and some compression, and a bit of searing. The owners were not there anymore, of course, but not for the reasons Kenshi would have expected.9

Morimoto, the master kite-maker who happened to be visiting with two wealthy cousins in that house at Moment Zero, had walked away with only the most minor scrapes and bruises. The triple-tiered roof and the thick expensive wood, combined with the capricious nature of the bomb effects, rendered the house just strong enough to shield three men as they sipped tea on the ground floor. Morimoto and his cousins had simply walked away from the very eye of a nuclear detonation, and walked into the record books as charter members in one of history’s most exclusive survivor minorities. The large house, with its broad beams and layers of thick tiles, must have absorbed just enough of the gamma rays, X-rays, and neutron spray to spare their lives—and the near light-speed blasts of heavy nuclei evidently missed the Morimoto house entirely.

Still, as he climbed out of the steaming wood-and-clay pile in which the fire had been miraculously blown out, Morimoto walked into a dusty wilderness with an awareness that he was suddenly very thirsty, and his skin felt as if every square centimeter had just become sunburned. His stomach and his intestines also ached, as if his insides, too, had been sunburned. He felt disoriented and confused, and by now Morimoto was beginning to suspect that even his brain must have been slightly sunburned. And after he stood atop a ridge of wreckage, and looked through breaks in the smoke, his disorientation multiplied. Normally, he would not have been able to see the mountains or the weather station’s transmission tower from this location because there were tall buildings in the way. But the obstructions were all gone, now. The city was . . . flat. The whole thing. Amid sheets of shifting dust, he could recognize only burning sewing machines, concrete cisterns, blackened bicycles and streetcars, and piles of reddish-black flesh everywhere, a few vaguely in the shapes of human figures, or occasionally in the shapes of horses.

The thirst and the burning sensations intensified quickly, and Morimoto began to vomit—the first signs of gamma ray and neutron dosing, which blended undetectably with a shock state in which an unknowable interval of time had passed before the kite-maker realized that he had wandered off alone and could no longer see his cousins.

More than almost anyone else in the city this day, Morimoto would be able to tell future historians that his troubles were only beginning. He knew that Hiroshima, though overflown by bomber groups on their way to Osaka and other city targets, had been left unharmed. He heard many rumors about why—including the ever popular, “Hiroshima has too many gardens and shrines and is too beautiful to be bombed.” But now Morimoto was among the first to conclude correctly that the Americans must have spared Hiroshima for something special—for how else could the designers of a new weapon hope to understand the damage wrought if the city were already carpeted with craters or eradicated by fire-bombs? If there were more of these special bombs to come, then they too would come to those cities intentionally left in pristine condition.

Most of Morimoto’s family lived in one such city, Nagasaki—so it was from logic, and not from a superstitious dread, that he had come to understand with a heartfelt certainty that his wife and children would be next, that the bomb was about to follow him home. But being followed did not matter to Morimoto.

If I am to die, he decided, let me die with my family. So let me go back to Nagasaki.10 And from such logic, history was destined to receive two impossible shock-cocoon perspectives from the same person: Ten to twelve kilotons at such close range—within a radius of 0.8 kilometers—as to seem almost directly overhead, and nearly thirty kilotons at 2.4 kilometers (a mile-and-a-half) away.11

Assembly Prefect Takejiro Nishioka had been completely shadow-shielded behind a tall ridge as his train approached Kaidaichi Station in the hilly suburbs of Hiroshima. The prefect had observed a glowing, reddish-yellow ring in the sky—huge and rocketing up from behind the hills in the direction of the city. As it faded into a cauliflower billow of multicolored vapor, soldiers on the train announced that an ammunition stockpile must have exploded. Nishioka knew better.

No ammunition explosion had ever behaved like the cloud over Hiroshima. From almost this same distance, Dr. Hachiya’s friend Hashimoto watched as, on either side of the rising column, “beautiful” smaller clouds spread out like a golden screen. “I have never seen anything so magnificent in my life,” Hashimoto would explain. “[The cloud] was as clear-cut as if a straight line had been made in the clear blue sky. Other straight lines spread out one after the other.”

Dr. Michihiko Hachiya survived under the same coal-dark cloud that enveloped the Ito boy and the Sasaki family. “I tried to picture in my mind, the beautiful sky with the golden screen [Hashimoto] had described,” Dr. Hachiya would write later. “While he was admiring the sky, we were trying to escape our ruined homes and were wandering through a darkened town. There was a vast difference between what those inside and outside the town had to say.”12

Prefect Nishioka did not have time to admire the fire in the sky. He had sensed, even behind the shadow of a mountain, that the pika (the flash) radiated from a single, point-source explosion. He knew this, and he knew more. He knew of whisperings about new weapons; and he knew, worst of all, that the war was drawing very near the end. He had been returning south from Tokyo with instructions to withdraw publishing facilities, administrative barracks, and whatever great works from antiquity might be saved into mountainside vaults.

During the past week, while Nishioka planned for the end and while vast portions of Tokyo lay under the black shroud of a fire-bomb raid, Professor Yoshio Nishina and his student Eizo Tajima expressed bitter regrets that the late Third Reich never shared the fruits of its uranium-refining facilities. The scientists estimated that given current production rates, working twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, the country’s two cyclotron accelerators might produce enough fissile material to assemble a single atomic bomb in about the year 2020. The plans for a heavy-ion relativistic shotgun weapon did not appear to be progressing much faster. Using power from the large dynamos at the Sakidaira plant, they had managed to prove that nuclei of gold were less easily scattered and more easily focused than iron nuclei—and in theory it was but a simple matter to aim particle beam weapons at B-29 bombers. But in practice, they would need a giant, ring-shaped accelerator nearly two kilometers in diameter, and the magnetic cannons would have to remain stationary, essentially anchored to the giant ring. The machines were therefore vulnerable to being neutralized even if the enemy chose not to attack the dynamos. All that the Americans, the British—and soon the Russians—needed to do was choose not to fly within range.13

Dr. Nishina had asked if he should continue with his plans for the accelerator ring. The Emperor’s representative did not answer.14

And so it came to pass that Nishioka, unlike the officers on his train, understood at once what had probably happened to Hiroshima. The soldiers needed a little more time to grasp the magnitude of the problem. As a precaution, they ordered the train to stop at Kaidaichi Station and to remain there until they made contact with the city. They shortly discovered that the phone lines were all dead, and even the usual daytime radio broadcasts had ceased. Then, from the direction of Hiroshima Station, came a train. All of the coaches had lost their windows, and apparently most of their passengers as well—save for a few stunned souls, looking out with blank expressions on their faces. The cars were all smoldering. At least two were actually afire. The train did not stop. The engineer, looking more like a scarecrow than a man, leaned out the portside window and vomited foaming streamers of bile, and he either did not care or derived a perverse delight from the fact that he was picking up speed and fanning the flames as he passed.15

The soldiers on Nishioka’s side of the tracks immediately ordered the passenger coaches unhooked from their train. They took command of the locomotive and decided to proceed at once toward the stricken city. Nishioka, shaking the image of the scarecrow engineer out of his mind, ran after the crew, flashed his credentials, and ordered them to take him along in the cab of the engine. He did not know it yet, but he had just embarked upon one of history’s most incredible journeys.

Within minutes of turning the curve of Kaidaichi Hill, Nishioka and the soldiers began to be confronted by lines of the walking wounded, following the railroad tracks away from the city. Pressing slowly and cautiously ahead—blowing the whistle to signal Make way! Make way!—they noticed that the burns on the refugees became progressively worse, and increasing numbers of the wounded were murmuring in low voices, “Water . . . Water . . .”

As they drew closer to the Cyclopean curtains of black smoke, the railroad tracks began shifting out of line and the locomotive was forced to stop.

The prefect decided to continue on foot toward the appointment he had arranged two days earlier at the home of Field Marshall Hata. Nishioka had a reputation for punctuality, and neither tsunami warning nor typhoon had ever made him late before. He was not about to let an atomic bomb break his spotless record.

Even after Nishioka discovered that the ground between the trapped train and the field marshal’s house was sprouting little flickering jets of strange fire, preserving his reputation obsessed him—no matter how disturbing those flames appeared to be. They emerged like miniature volcanic plumes, as if from burning bits of sulfur. They could have been extinguished easily by stepping on them as he passed, but he did not want to do that, believing later that merely by walking among the little jets he had exposed himself to radiation that caused his feet and shins to bleed beneath the skin.

For all of this, he was on time. The field marshal was late, despite the fact that his house had been shaded by a hill from the full effect of the pika-don (what people were already calling the flash-bang). Nishioka expected that Hata would still have been inside at such an early hour, but he was met by an elderly officer whose face had first- and second-degree burns on one side and whose uniform had been torn apart. He asked for Hata, and the officer replied that he believed the field marshal to be dead.

The officer added, “I believe Hiroshima has been hit by an atomic bomb.”

“I believe so, too,” Nishioka said, and then decided to follow the tracks a little closer and see for himself.

A bridge stopped him. Its steel was sagging grotesquely and the wooden railway ties were on fire. No more survivors were crossing over from the city, but some of their cats had made it across. Six of them, their hair only slightly singed, were licking a ropy tangle of intestines hanging from a wounded horse that seemed not to notice.

Nishioka did not particularly like cats. About the time Kenshi Hirata reached Ground Zero, the prefect was deciding he hated them. He also decided that there was nothing more he could accomplish in Hiroshima, and that he could better serve the empire by returning to his own regional headquarters at once with news of what he had seen.

Following the tracks away from the sea of smoke, he met a schoolboy who had been drafted into factory work by his teachers. The contours of the land—and especially Hiroshima Castle’s moats and deflecting stone ramparts nearby—had somehow compressed the shockwave and focused it like a cannon shot through his school-turned-factory. The boy explained over and over again that he appeared to be the sole survivor. He was headed away from a zone, Nishioka later learned, that was most heavily exposed to radioactive fallout (near the Misasa Bridge). The boy reportedly walked directly through the black rain zone, following a set of railroad tracks past Hiroshima’s Communications Hospital and toward one of the suburban railroad stations—toward a place his family had arranged as a gathering point in the event of a severe air raid.

As they parted paths, the prefect gave the boy most of the provision of rice and water he had been carrying, and also a card with his name and the address of his headquarters, offering help and asking that his family contact him later. But he never did hear from the boy again, and he would wonder if this was because he and his family were to be counted among the dead or because they had counted him among the dead. The latter seemed just as likely as the former, because the address on Prefect Nishioka’s card was the hypocenter of Nagasaki.

Historians would never be able to pin down the identity of the boy with any degree of certainty. And yet Hiroshima’s Ito family would bear the distinction of a survivor’s account that contained familiar congruences—which resounded hauntingly like the other side of Nishioka’s story. Tsugio Ito’s older brother Hiroshi was a schoolboy who emerged as virtually the sole survivor from the Central School and who followed a set of railroad tracks eastward out of town, toward a pre-arranged family gathering place near the prefect’s position. During a time in which food had become so scarce that few if any people ever gave rice away to strangers, the Ito boy reported to his family that a tall, authoritative stranger had given him food and offered him help.

During the hours that followed the encounter, nausea and weakness attacked Hiroshi, went away, then came after him more fiercely, causing him to vomit up the rice he had been given. Whether or not Hiroshi Ito was the same boy the prefect encountered, history dealt the Ito and Nishioka families each an improbable hand, from the bottom of the deck. Heading off in opposite directions, it mattered little whether the schoolboy and the prefect eventually went to Nagasaki or to the Hiroshima suburbs. Nishioka would later record that the demon of atomic death seemed determined to stalk after them—for it was already deep within their flesh, sharpening its claws and waiting to pounce.16

Kenshi Hirata would probably have escaped with no radiation injury at all had he not gone into the center of the blast area searching for Setsuko. Once he breathed the dry dust, then cleared the dust from his throat by drinking brownish-black water from a broken pipe, his cells were absorbing strange new variations on some very common elements. These new incarnations, or isotopes, tended to be so unstable that by the time he awoke in the morning most of them would no longer exist. Like little energized batteries, they were giving up their power. Unfortunately, they were discharging that power directly into Kenshi’s skin and stomach, into his lungs and blood. The quirk that spared him a lethal dose was the initial collapse of the shock bubble and the rise of the hot cloud. A substantial volume of pulverized and irradiated debris had been hoisted up into the cloud, and most of the poisons had already fallen kilometers away as black rain. Even in terms of radiation effects, in its own, paradoxical way, the central region of Ground Zero was sometimes the safest place to be.17 It was all relative, naturally: Mr. Hirata’s neighborhood was still hot with radioactivity; but places farther away were even hotter.18

By nightfall of that first day, Kenshi had positively identified a particular depression in the ground as his home. Only a day before, the house and garden were surrounded by a beautiful tiled wall—and now, chips of those distinctive tiles were strewn through the embers. The large iron stove that had heated bathwater for Kenshi and his bride seemed to have been hammered into the ground, but it still appeared to be located in the right part of the house. Only a few steps away, he unearthed kitchen utensils, which though deformed by heat and blast looked all too painfully familiar. They were gifts from Setsuko’s parents.

Kenshi had an odd instinctive feeling that the ground itself might be dangerous, and that he should leave the city immediately. The thought that stopped him was Setsuko: If she is dead, her spirit may feel lonely under the ashes, in the dark, all by herself. So I will sleep with her overnight, in our home.

Around midnight, he was awakened by enemy planes sweeping low, surveying the damage. The sky, in a wide, horizon-spanning arc from north to east, glowed crimson—reflecting the fires on the ground. Though there was little left to burn in what American fliers were already calling Ground Zero, flames grew all around the fringes of the bomb zone, creeping outward and outward.

The planes circled and left. Kenshi put his head down again, upon the ashes of his home, and lay in the otherworldly desolation of the city center. The silence of Hiroshima was broken intermittently by more planes and by explosions near the horizon in the direction of the waterfront and the Syn-fuel gas works. As the ring of fire expanded to the gas tanks, there were no working fire hydrants or fleets of fire trucks, and only a handful of firefighters were left alive to prevent the tanks from igniting. Kenshi heard huge metal hulls rocketing into the air on jets of flame, crashing back to earth one by one, and shooting up again. But Ground Zero itself was deceptively peaceful, and the noises that reached Kenshi from the outside did not trouble him. He was too exhausted and too filled with worry about Setsuko’s fate. If anything, the distant crackle of flames—even the occasional pops and bangs—lulled him into a deep slumber.19

Sumiko Kirihara’s and Sadako Sasaki’s families tried desperately to get out of the city, but by midnight many of the people Prefect Nishioka had seen staggering away from Hiroshima were finding the roads blockaded by residents of the outlying villages. In the countryside, during the space of only a few hours, the survivors had been transformed into fugitives, as localized councils made crystal clear through megaphones. By argument and by the occasional drawing of weapons, local authorities directed the walking wounded back toward the pyres and the places where black rain had fallen—and, though they did not know as yet that such poisons existed, toward the radioactivity.20

Even before the bomb fell, city dwellers had found themselves unwelcome. After Osaka was cluster-bombed with incendiary weapons, no one wanted to live in any city. Children were sent off to relatives if they happened to have kin in the countryside. Satoko Matsumoto, another woman whose family had fled to the river with the Kirihara and Sasaki families, had hoped they could all cross together over a railroad bridge to the other side of a mountain, where some of her father’s personal property had been sent a month earlier for storage. Then she remembered what her father had said at the time: that the townspeople were willing to accept luggage for safekeeping, but all refugees would be turned away. There were already food shortages in farming communities overtaxed by the military. Extra mouths to feed from the city, they had said, would push whole families over the edge from severe rationing and hunger to starvation.

Around the hour Kenshi Hirata laid his head down near his wife’s grave, the first refugees returned to Hiroshima bearing unbelievable news of the “outlanders” turning them back with threats and even with lethal violence. So the three families decided to find an open space where they could spend the night.

Satoko Matsumoto’s father would be stricken by “atomic bomb disease” in only a week. Developing huge purple bruises under his skin, losing his hair in large clumps, and bleeding cupfuls of blood through his nose, Mr. Matsumoto would stand up one evening, gaze at the setting sun, and without any warning or fuss, fall dead.

That first night, Satoko lay on her back and watched towers of smoke drifting up against the stars and blotting them out. Only at their bases did the towers dance with reflected light from the flames. Higher up they ceased to reflect anything at all; rather, they absorbed the light as if someone had spilled ink across the heavens. Like her father, she had suffered no visible injuries; still, she found it painful to spend the interminable night lying on her back under that oppressive fried squid smell, listening to the fires consuming what was left of the city. Occasionally, the black shadows of American reconnaissance planes passed overhead. And when the smoke finally shifted to reveal more than half the sky, Satoko beheld more shooting stars than she had ever seen before.21

Something managed to send a chill up her spine—during a night that had already been so full of fearful moments that just one more seemed bound to pass without her notice—and yet Satoko was chilled to the bone when a woman mentioned that the unusual number of falling stars must mean that more people than they had already seen die had only now joined the dead, or were about to die.22

The first soldiers to reach the hypocenter came only an hour ahead of sunrise. The War Ministry had sent them in with stretchers—for what purpose, they could not understand. “There was not a living thing in sight,” one of them would later recall. “It was as if the people who lived in this uncanny city had been reduced to ashes with their houses.”

And yet there was a statue, standing undamaged in a place where not a single brick lay upon another brick. The statue was in fact a naked man standing with arms and legs spread apart—standing there, where everything else had been thrown down. The man had become charcoal—a pillar of charcoal so light and brittle that whole sections of him crumbled at the slightest touch. He must have climbed out of a shelter about a minute after the blast, chased perhaps by choking hot fumes from an underground broiler into the heart of hell. The fires killed him and carbonized him where he stood.23

The soldiers found an even more disturbing statue, covered in gray ashes. It appeared to have spent the last moment of its life trying to curl up into a fetal position. One of them probed it with a rod, expecting it to crumble apart. Instead, it opened its eyes.

The soldier flinched and asked, “How do you feel?” There seemed to be nothing else to say.

Instead of saying what he felt like saying—How do you think I feel, you moron?—the man replied that he was uninjured and explained, “When I came home from my job, I found that everything was gone, as you see here now.” The man insisted he needed no aid in leaving, nor did he wish to leave.

“This is the site of my house,” he said. “My name is Kenshi.”24

During that first night, Akira Iwanaga had taken shelter in a tunnel near the ruins of his boarding house. He marveled at the power of the air-burst, nearly two miles from the hypocenter. “All the glass that had been in one side of the house was embedded deeply, in spears, in the opposite wall,” he would report to his managers at Mitsubishi headquarters. On that first day and night of the bomb and the fire worms, he had crossed paths twice with his roommate and fellow ship-design engineer Tsutomo Yamaguchi, but neither man saw the other.

Akira had been standing outside Hiroshima’s newest Mitsubishi plant when the pika-don was born. He was shielded from its full force by a low hill, at a distance of 3.7 kilometers. Even at a radius of slightly more than two miles, and behind a hill, Akira had felt a strong wave of heat in the air, followed quickly by a high wind and whirling dust. Overhead, the mushroom cloud’s cap had seemed to glitter with flashes of bright golden lightning. And then had come black rain and a darkness that swallowed all the sounds of the world, and which seemed to know no end.

Sunrise now brought only the briefest respite. The winds—which had been drawn into the pyre like warm air drawn into the eye of a typhoon—were finally stalling and abating. The fire worms were dying. By now the arc of flame beyond the hypocenter burned with a steady, crackling roar, and Akira could begin to see clearly in the strengthening daybreak.

The river was still glutted with bodies and debris, just as he had seen it at sunset. In the outside world of countryside villages, the water-bloated bodies and the tide of ravenous black flies that seemed to be rising everywhere would have been shocking. But Akira now believed he was beyond the point at which he could be shocked. And then daylight continued to strengthen, revealing a young and hauntingly petite woman carrying a dead child on her back. She was insane, screaming a scream that only grew louder with time. There was a second girl whose mind had just as clearly been wiped away. Only twenty-four hours before, her smile must have been absolutely beautiful. Even now there was something mournfully beautiful about her. She had apparently escaped without any flash burns and seemed completely uninjured . . . except for the huge slash across her abdomen. Having propped her back firmly against a wall, she seemed to have spent much of the night carefully rearranging her intestines and trying to push them back inside, but the baby—which appeared to be only halfway to term—had come out with her insides and died and she did not seem to know quite what to do with it . . . whether to leave it outside her body or to continue pushing. She gave a hideous grimace that became a smile, then flopped over to one side, dead—while the screaming woman with the broiled and bloated child on her back showed no signs of growing hoarse.

Akira bolted, slipped on a loose brick pile, fell hard on a splintery shard of scorched wood, and let out a scream of his own. He stood up and began running again, slipped on something soft, recovered his pace this time without falling, and continued running as fast and as far as he could, putting as much distance as possible between himself and those horrible beautiful girls.25

Dozing nearby in a half-sunk fishing boat, Akira’s roommate, Tsutomu Yamaguchi, dismissed the screams in the Hiroshima wilderness as merely another pair of anonymous minds that had snapped. He had not eaten for nearly twenty-four hours but had managed to keep dehydration in check by forcing himself to drink dirty water from broken pipes. The shipbuilder still carried most of his ration of two biscuits, but was having trouble keeping down even a few sips of water. Appetite had failed him hours earlier.

During the night, a soldier told Yamaguchi that the local Mitsubishi plants appeared to be permanently out of action, and that any surviving engineering personnel should return to headquarters in Nagasaki. Yamaguchi had assumed that the rail services were every bit as dead as the Mitsubishi shipyard, but the soldier informed him that there were plans to send a train out of Koi Station to Nagasaki in the late afternoon.

After only two hours of rest in the ruins of the boat, Yamaguchi felt well enough to set out for Koi. Normally, he could make the trip in forty-five minutes. But now? Who knew if he would ever reach the station, much less Nagasaki?

The soldier had assured Yamaguchi that as a high-ranking naval engineer, a priority seat would be available. The shipbuilder no longer cared very much about military priorities or the war effort. All he wanted was to get home to his wife and his infant son.

With nothing else in mind, he was able (with varying degrees of success) to harden his heart against all that the grim sunrise revealed: a mother singing a lullaby to her dead child, a horse’s head burning like an oil lamp with an eerie, bluish-green flame. Yamaguchi came across a body that at first appeared to have been completely shielded from the searing rays, and then he realized that the shielding had only protected the man from his midsection down to his feet. The upper third of him was a carbonized corpse whose features had been eroded by the wind. The musculature and even the ribs were being carried away as soot on the morning breeze, revealing a blackened heart. Yamaguchi noted for future reference that whatever had shielded the man’s lower body and turned his head and chest into loosely packed soot could easily have been worse the other way around—leaving the heart and eyes and brain intact while allowing the victim to see his bared pelvis and femurs before he died.

The engineer had to cross two rivers on his way to the station. The narrower of them no longer had a bridge, but in the shallows bodies were piled up like a natural dam that could also be crossed like a bridge. Even when he tried to keep his mind focused on nothing except the recollected faces of his wife and child, crossing that bridge pained him severely.

At the broader of the two crossings, he encountered an even more challenging bridge: a high railroad trestle whose iron frame was sagging ominously, as if on the verge of collapse. Almost all of its wooden ties had been burned, so he was obliged to belly-crawl and straddle and pull his way along a narrow steel track rail, as if he were a trainee in a high-wire act.

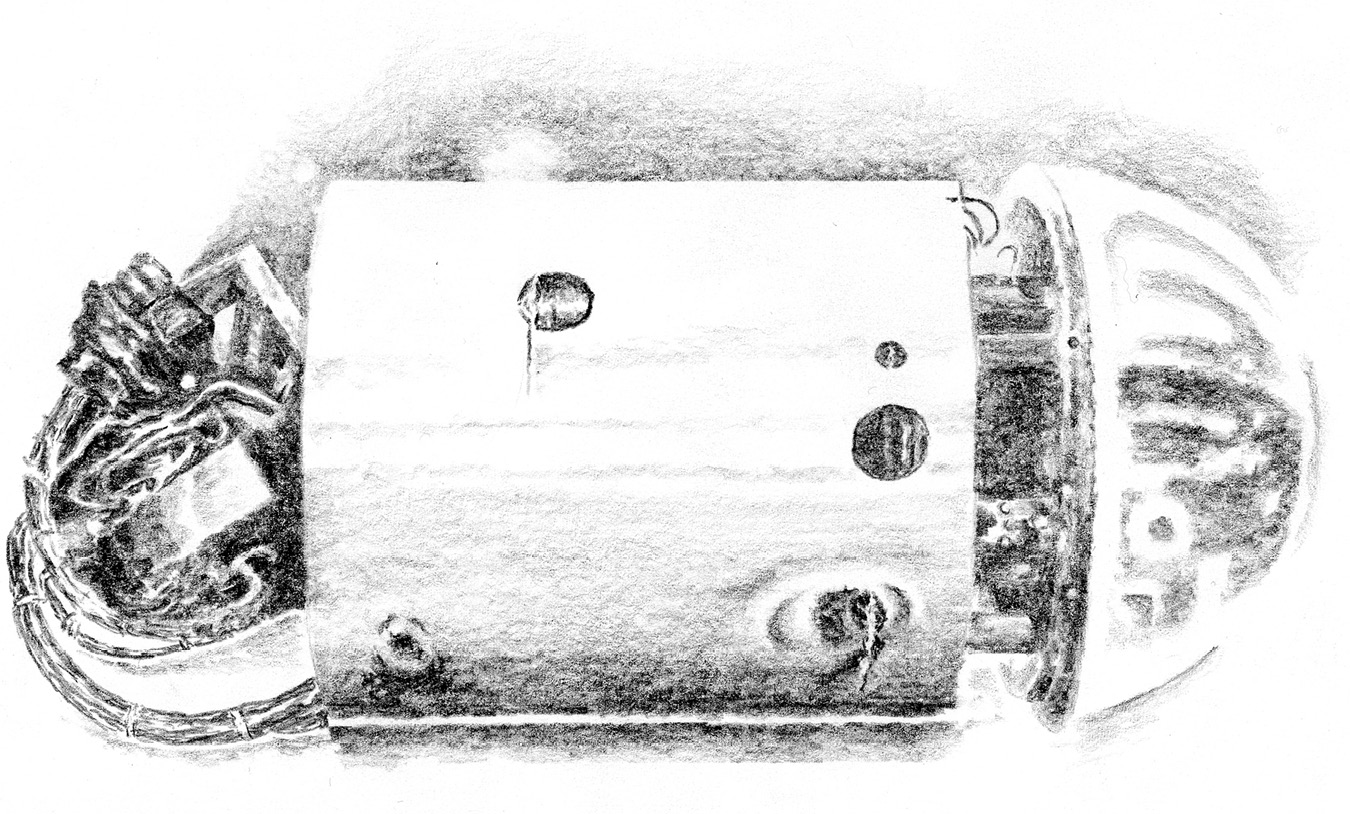

En route to the train station, the engineer and Prefect Nishioka passed near several military officers gathered around a large aluminum cylinder. The object was flash-burned on one side and appeared to have come crashing to earth like a meteorite. Yamaguchi had actually seen the cylinder, and other cylinders like it, being dropped over the city on parachutes, only seconds ahead of the flash. Inside the canister, the officers found a radio transmitter attached to atmospheric and scientific monitoring devices.26

One of the three scientific instrument packages dropped by Charles Sweeney and Luis Alvarez from the Great Artiste, August 6, 1945. Alvarez had tucked a letter inside each cylinder, addressed to former colleagues in Japan. Suspecting that his old friend Yoshio Nishina had been leading Japan’s race toward development of nuclear weapons, he hoped Nishina would convince the warlords that in addition to the experimental fire-bombs then being dropped across the homeland, atomic bombs had just been added to the B-29 fleet’s tool box. [Illustration: CRP]

What they did not tell the engineer or anyone else passing by—what only the officers and one or two key officials knew at this stage—was that they had discovered an envelope among the pressure wave, gamma ray, and neutron sensors. The envelope contained an appeal addressed to Professors Ryokichi Sagane, Nishina, Tajima, and the rest of Japan’s leading physicists. The appeal came from atomic bomb scientist Luis Alvarez, who four decades later would leave his mark on the history of nuclear arms reduction with the discovery of the “nuclear winter” effect.

“You have known for several years that an atomic bomb could be built,” the letter began, “if a nation were willing to pay the enormous cost in preparing the necessary material.” Alvarez continued, “Now that you have seen that we have constructed the production plants, there can be no doubt in your mind that all the output of these factories, working 24 hours a day, will be exploded in your homeland. . . . As scientists, we deplore the use to which a beautiful discovery has been put, but we can assure you that unless Japan surrenders at once, this rain of atomic bombs will increase many-fold in fury.”

Alvarez was not telling the whole truth, of course. The end of World War II was more a game of poker than chess, and like any good poker player, the American did not hint at the cards he really held. The fact was that the factories alluded to could produce barely more than two troy ounces per day of the necessary material. The production facilities were only now beginning to successfully expand, now that it had been demonstrated that the machine would actually work. Once the next bomb was dropped, another would not be available until September or October; but the gradually accelerating production of fissionable metals was presently moving into a trajectory that seemed fated to become unstoppable, even if the war could be ended in just a few short weeks. No one seemed capable of predicting what would happen next, not Luis Alvarez, not any of the soldiers who flew the atomic mission with him, not even the president of the United States—truly no one.

Whatever happened tomorrow or the day after really had very little to do with American behavior or with Japanese behavior. What it all came down to was that most of human history was fated to be forged by primal instincts, and not by civilized thought. The dawn of atomic death was a distinctly human story, told by tigers with uranium-and-plutonium-tipped claws.

Once upon a time there existed only three atomic bombs in all the world. The tigers tested one in the New Mexico desert, to be certain that the machine would work. Three weeks later the other two were dropped.27

Even when Kenshi realized that the cloud had risen directly over his home, he prayed and held out hope that Setsuko might have somehow escaped harm. When he left the dockyard, he had packed a few extra biscuits for her. Now, a day later, he dug on all fours into the compressed ashes of his kitchen, descending nearly a half-meter—almost knee-deep. Whenever he paused to eat a biscuit or to sip water from a broken pipe, he sprinkled a share of the food and water ceremonially onto the ground—an offering to his bride of ten days.

As the August sun climbed higher and a snowfall of gray ashes blew through, the pipe stopped dripping. Kenshi was soon out of water as well as running low on biscuits, but he continued digging, hoping against knowledge that his failure to find any bones meant that Setsuko might not have been home when the flash came. For a while, believing he might have dug deeply enough to have found Setsuko if she had died at home, Kenshi left to search the nearest riverbank, wishing he might find her miraculously among the living. But hope died the moment he understood the condition of the few who were still moving among the bodies. Kenshi would never be able to forget their desperate faces, calling for “Water . . . water . . . water,” while he cried out for Setsuko. Finally taking some small measure of relief from the realization that Setsuko was not among this suffering multitude, Kenshi Hirata walked back toward the center of Ground Zero, and continued his excavation of the kitchen.

As exhaustion, thirst—and now hunger—began to compete with the first mild signs of radiation sickness, three women from his neighborhood returned to the ruins. Like Kenshi, they had been away, sheltered from the pika-don. The oldest of them, the head of their neighborhood association, had rediscovered the place where emergency rations were buried and had directed the excavation of three large sealed cans of dry rice. Seeing Kenshi, and hearing his pleas for anyone who might have encountered Setsuko, she went straight off to a nearby pit in the ground that was filled with glowing red coals of wood. She mixed some of her own water ration with rice and cooked a bowl of mildly radioactive gruel for Kenshi. He would recall later that he was moved to tears by the kindness of this woman. He never saw her again.

After he ate the bowl of rice soup, he felt reenergized despite slight waves of nausea and resumed his search for Setsuko.

He excavated the entire kitchen, knowing that his wife loved cooking more than almost anything in the world, and that she fancied herself a top chef who could turn even the most meager rations into the most subtle flavors by coaxing spices and herbs from what most people called termites and weeds and citrus ants. The kitchen, he decided, was where he would most likely have found her at 8:15 a.m.—planning how to bulk up a cup of stale soybeans and turn it into what she had promised to be “a taste like walking on a cloud.”

When the dust of the kitchen had produced not the slightest trace of her, Kenshi began to grasp again, ever so slightly, at hope. He was soon joined by ten men who worked in the city’s sawmill. They knew the couple well and had heard of Kenshi’s distress.

They moved from the kitchen to the living room, excavating almost knee deep, and not a single trace of bone was found.

“She is not here,” Kenshi said. “She is still alive somewhere.”

“In order to make sure, we must dig a little deeper,” one of his friends said.

Minutes later, hope died again. His friend unearthed what seemed to Kenshi to be only a bit of a seashell.

“We both love conches and giant clam shells,” Kenshi insisted. “Setsuko uses them as table decorations!”

But already he knew in his heart that it was a fragment of human skull. The men quietly stepped back. Suppressing an uneasy feeling, Kenshi excavated gently with his fingertips, slowly widening and then deepening the area from which the “shell” had come. He touched little white scraps of spine, and found in them a pattern that indicated to him her final moment. She had been sitting when . . . it happened.

From the kitchen he excavated a metal bowl, singed but otherwise completely undamaged. Kenshi recognized it as the very same bowl he and Setsuko had brought with them from her parents’ home on the train to Hiroshima, only ten days before.

Ten days, he lamented, and this poor girl’s bones are to be put in this basin that she had brought with her from her native place.

He was thirsty under the broiling sun of midsummer. Sweat had formed long streamers down his back and his trousers were soaked. He felt faint. His friend from the sawmill offered him water and he drank, then sprinkled some of the water over the basin—in the sense of giving his wife the last water to the end of her short life.

“The lumber mill is gone and there is no guessing what will become of us now,” his friend said, then announced that he and his wife had been hoarding a small ration of fine white rice and dried fish, just in case the gradually worsening conditions came down to what westerners called “a rainy day.”

“Well, it’s been raining fire and black ice and horse guts,” the mill owner said. “So, this must be the day.”

He invited Kenshi home for a late but hardy lunch, and offered a place to stay until he decided where to go next.

Kenshi had already decided. As a surviving member of Mitsubishi management, he would be able to get priority seating on any trains still running. “If I can get to Koi or even all the way out to Kaidaichi Station,” he said, cradling the bowl of bones close to his chest, “then I will be able to find a way to bring Setsuko home to her parents.”

“Then all the more reason for you to have a good meal before you leave,” his friend insisted.

On the outskirts of the city, the mill owner’s house had survived behind a hill with only a few roof tiles dislodged. Nausea came and went, which made it easier for Kenshi to eat slowly and to keep his portions small. He did not want to take too much of the last good meal in town for himself, and away from his friends. All the while, the bowl from his own kitchen lay at his side. From the bones of his wife, isotopes of potassium and iodine were being liberated. They settled on Kenshi’s trousers, and on his skin, and in his lungs.

While they ate, a young soldier came to the door with news that Hiroshima Station might never run again, and all of the high-priority seats at Koi Station were already taken for the afternoon of August 7. No trains were running out of Kaitaichi, owing to what the sixteen-year-old message-runner called “the most amazing train wreck ever!”

He explained excitedly how a train leaving Hiroshima during the flash had been fried so severely that even its deadman switches must have failed: “The thing shot right through Kaitaichi and just kept on flying. They say it was doing at least a hundred-and-fifty K when it finally hit a truck in a crossing and went off the rails!”

Kenshi merely thanked the boy for his report and asked him if any trains would be leaving Koi tomorrow.

“Yes,” he said. “There’s one leaving at 3 p.m., and you have provisional seating—which means you’re on it, as long as you can get there.”

Kenshi decided to make an early start. Many roads and bridges had ceased to exist, and how long the walk to Koi would take was anybody’s guess. He filled his canteen and put two biscuits and a few grains of rice into his pants pocket, then cut some strings and wrapped a cloth tightly over the top of the basin so that Setsuko’s bones would not spill if he tripped on the debris that filled the streets.

Before he left, Kenshi asked his friend for permission to pick a flower from his garden. Then, saying his thank-yous and good-byes, he went down to the river, where he threw offerings of a flower and rice grains into the water and bowed three times, in accordance with a Buddhist tradition that acknowledges a place of the dead.

Bodies were now being pulled from both sides of the river, and on the road ahead, mass cremations had already begun.

How, Kenshi wondered, was he going to tell Setsuko’s parents what happened to her? He could think of nothing else. He did not know yet that he would soon have much else to think about. It might even be said that his rendezvous with history these past two days had been merely the twilight before the dawn. Kenshi Hirata would reach Koi Station with time to spare; and at three o’clock on the afternoon of August 8, he would set out to bring Setsuko’s bones home to her parents, aboard the last Nagasaki-bound train to depart Hiroshima.28