On August 6, 1945, after President Truman announced the ongoing development of bombs even more powerful than the one dropped on Hiroshima, few outside of the Kremlin or Japan’s Imperial Palace would have imagined that only one more nuclear weapon existed in the arsenal. Nor would any among the millions of people gathered around radios in the living rooms of the world have doubted Truman’s statement that the Hiroshima bomb “had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT.” Officially, it would be listed in the history books as yielding 22 kilotons; yet subsequent scientific evaluations would run considerably lower. Even the 509th Composite Group’s Timeline of Operation Centerboard (the Hiroshima Mission) eventually listed the final yield at only 12.5 kilotons. Compared to the bomb that would soon ignite over Nagasaki, the Hiroshima weapon was weaker, by at least half. The leaves on the Hiroshima-facing sides of trees were flash-dried out to a radius of almost seven miles. The flash from the Nagasaki bomb would extend this same effect nearly eight times as far.1

Before he climbed aboard the scientific observation plane Great Artiste, physicist Luis Alvarez had assured pilot Charles Sweeney that he expected the bomb to detonate; but not necessarily up to its maximum intended strength. Sweeney did not know very much about the interior of the “Little Boy” device. Alvarez knew the beast inside and out, the power and the geometric precision of every uranium ring, every beryllium-polonium plug. He knew this, and much more. He understood that while it took the efforts of an entire government industry to tease naturally occurring atoms of uranium-235 out of the rocks, and to slowly enrich the neutron-emitting metal to higher and higher levels of purity, putting uranium together into a bomb design that would work was a fairly straightforward engineering problem.

Given the right purity, in the right amounts, an explosive result could be achieved simply by dropping one mass of U-235 down a long drainpipe, on top of another, with one of several initiator/enhancer elements smashed in between. The challenge lay in obtaining the right materials, at which point even an amateur (albeit a sharp-witted amateur) could improve the efficiency of the drainpipe model to a yield of about 5 kilotons. Professionals like Alvarez spoke in terms of 20 kilotons, and believed they could enhance a uranium weapon up to 50 kilotons with reasonable ease.

Somewhere in the sequence of production and delivery of the weapon, a design flaw, a misunderstanding, or a miscalculation had crept into the “Little Boy” device and diminished its yield. Probably, no one would ever know the cause. The weapon took all evidence with it the moment it came apart into electron-stripped nuclei.

Of all the design challenges, the greatest of them lay not in getting uranium to undergo fission but in coaxing it to fission efficiently and preventing it from detonating prematurely.

Few besides Luis Alvarez and pilots Paul Tibbets and Charles Sweeney knew the true extent of worry and debate that had existed, over how ready for detonation “the gadget’s” internal geometry really needed to be at the moment of takeoff. If already primed in Enola Gay’s bomb bay, the carefully divided uranium masses in the aft end of the bomb could all come into contact with the cone-shaped needle in the bomb’s nose and undergo partial fission if the plane crashed or even if it hit a very hard bump along the runway. The outcome of this scenario—which Dr. Alvarez called “an unscheduled energetic disassembly”—had five possible endings. None were good. The least of five worries would shoot tiny beads of molten uranium hundreds of feet in every direction, exhausting the greater portion of America’s (bomb grade) uranium supply and becoming a threat to the health of anyone who happened to be within breathing distance. At the high end of Alvarez’s five-point “Sphincter Scale,” a runway crash involving fire could easily trigger the bomb’s detonators, destroying the entire Tinian Island air base.2

The debate over how and precisely when to arm the device had been settled on the morning of August 5 by the crash of a B-29 on one of the runways. Up to that moment, the debate appeared finally to have been pointing toward a plan for taking off with the bomb fully primed and ready. Navy Captain William Parsons, a weaponeer from Los Alamos Labs, interpreted the August 5 crash as a final warning, and reversed the plan. He spent the afternoon practicing the arming and disarming of the bomb’s triggers until the skin on his fingertips began to wear thin from abrasion. Parsons refused to handle the explosive charges and the hatches with protective gloves. He insisted on learning the feel of every charge, plug, and screw thread during what promised to be a difficult procedure on a vibrating and rocking bomb-mount while Enola Gay and its two scientific escort planes flew toward their target.

Shortly before midnight on August 5, Parsons briefed the crews of the three planes that would actually fly the mission, stating for the first time that they would be carrying only a single bomb.3 No mention of atomic power was ever made. Indeed, Parsons’ navigator, Theodore van Kirk, knew nothing more beyond his own suspicion that a new kind of fire-bomb had been developed by the chemists.4

Russell Gackensbach, the navigator assigned to the photographic plane Necessary Evil, had made similar guesses about what they might be carrying; but even at this late stage, no one had told him, and he was under instructions not to ask. Gackensbach’s path to the Isle of Tinian and Necessary Evil had been long and strange—from Allentown High School to factory work as a bomb casing inspector whose obsession with aviation eventually placed him aboard B-17 Flying Fortress missions, operating the new navigation and radar devices—until, during the summer of 1944, transfer orders came seemingly out of nowhere, to a new base on the edge of Utah’s Great Salt Lake desert.

The base scarcely began to define the word “remote”—and that was the whole point of it, Gackensbach realized. The new commanding officer, Colonel Paul Tibbets, told his team only that the mission for which they were being trained would be something completely different, adding, “What you do here, what you see here, when you leave here, let it stay here.” All the way up to the night of August 5, Russell Gackensbach would recall, “They only told us what we needed to know to do our job, and we didn’t even know what our job was.”

From the start, even before the new B-29s left Utah, Tibbets had assured that nothing would be normal about their mission profile. He kept true to that promise. Through June 1945 they made training runs to target areas all around America, dropping bombs of various sizes and often bizarre shapes, including a large “pumpkin” with fins. As training progressed, the planes were streamlined and modified to fly higher, faster, farther—and with bigger loads. The “improvements” included stripping off all of the exterior guns, except for a single tail gun.5

“A few bursts and we’ll be toothless,” pilot Charles Sweeney observed; but he was not particularly worried. If the enemy sent up a picket of fighter planes, the maximum velocity of a Japanese Zero was only 350 mph. The B-29s flew at up to 450 mph. They could never be chased down, and if a Zero dove at them from directly ahead, it would only be capable of a single pass.

During the months that had elapsed since the February capture of Tinian Island from Japan, the island became a maze of runways, and the Emperor’s homeland was brought within range of massive B-29 raids. Ahead of Hiroshima, more than sixty cities already lay under black shrouds of smoke and ashes. In swarms sometimes three hundred planes strong, every sort of experimental incendiary chemical, from phosphorous to napalm, began to fall night, after night, after night.6

In Hiroshima, a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl named Hiroko Nakamoto had noticed that since at least February, schoolwork was moving steadily away from mathematics and calligraphy and increasingly toward assignments to help manufacture machine parts in the army buildings. She heard stories about other cities being bombed; but all of the radio broadcasters denied this, dismissing the tales as “exaggerations” about only minor damage. The radio told only of glorious victories against American ships by Japan’s elite pilots, and about successfully repelled American invasions of Saipan, Okinawa, and other outlying islands.

About the time Russell Gackensbach made his last training run before moving to Tinian, an older girl on Hiroko’s work detail had said, “I don’t believe we are being told the truth. I don’t think the war is going well for Japan.”

Hiroko hated the girl and called her a liar, wondering if the upstart might be pro-American and should be reported. But by then the air raid sirens were whooping and wailing at random hours, day and night. Above Hiroshima, the strange new, silvery planes called B-sans seemed only to be passing by at very high altitude, never dropping any bombs, as if little groups of two or three of them occasionally became lost, or as if they were by now becoming so confident in their command of Japanese airspace that they could afford to go sight-seeing.

During the course of only a few months, Hiroko and her classmates had witnessed their entire world falling into decay and despair. All the fuel and food supplies were beginning to run out; and the rate of decline seemed to be accelerating.

Photographs brought back to Tinian by Hiroko’s “lost” or “sight-seeing” B-29s were showing gunboats and fishing boats evidently out of fuel and anchored in the same places around Hiroshima, day after day, week after week. Except for trolley cars and the occasional military vehicle, all traffic on the streets of the city had been reduced to people on horseback or on foot or on bicycles.

On the day William Parsons nearly wore his fingers out perfecting his arming procedure for the Hiroshima bomb, there was little left to eat in Hiroko’s home except government rations of a reddish-brown grain called Korian—which in prior years was given only to horses. Families were also given a ration of something called “weed cake,” a food made literally from weeds. It tasted so nauseatingly awful that Hiroko had learned to burn the weed cakes until they turned into something very much like charcoal—“because,” she would record later, “the taste of the ashes was better than the taste of the weeds.”

Despite the food shortages, one of Hiroko Nakamoto’s greatest concerns was for the two albino mice given to her as pets by a local medical officer. Even the mice refused to eat the weeds and the Korian. For a while, Hiroko had been able to keep them alive with the shreds of radish leaves stolen from a farm. Briefly, her pets gained enough energy to use the little swing set she had made for them. “They played happily and I never tired of watching them,” Hiroko would recall; but by the time Russell Gackensbach was assigned as navigator aboard a plane named Necessary Evil, Hiroko’s supply of radish leaves had run out and her mice were dead from starvation. They were among the lucky ones.7

In another part of the city, a child named Keiji Nakazawa would live to tell how only now were the wealthy citizens who had wanted the war and who had called for “a fight to the death”—though often it was the sons of their neighbors who went off to war and died—only now, during the last days leading up to Moment Zero, were they beginning to feel the war’s burdens, including personal poverty and dwindling food supplies.8

On Tinian, Paul Tibbets had selected the aiming point for the bomb as the Aioi Bridge, the “T” Bridge that crossed Hiroshima’s Ota River, because it was a distinctive feature that could be immediately recognized by the bombardier, even at an altitude of nine kilometers (or 30,000 feet). The precise aiming point, like the very nature of the bomb itself, remained hidden from navigator Gackensbach and his flight engineer, James R. Corliss, as they gathered their gear and were escorted at 2:00, on the morning of August 6, to one of three planes—three planes, constituting less than one-fiftieth the normal contingent sent out on a fire-bombing.9 An inordinate number of the crew appeared to be civilian scientists, who had been appearing on Tinian in greater numbers lately, and who kept completely to themselves, speaking only when absolutely necessary.10

Everything about the August 6 launch had a surreal aspect. Chaplain Downey stepped forward and beseeched God to bring an end to war. Flashbulbs popped in the chaplain’s face as he spoke. Nearby, Paul Tibbets withdrew a box and spoke with his crew. He explained that the flight surgeon had provided pills—one for each man—in case the planes went down in enemy territory. The surgeon knew some of the methods of torture that could be expected; and he knew that most people talked under torture.

“I’ll give them to any one of you if you want the pill,” Tibbets explained. “Six minutes and you’re gone,” the flight surgeon had assured. “You won’t know anything.”

The men simply stared at the box—silently, except for Captain Parsons. “I’d like to have one,” the man from Los Alamos said. Tibbets understood Parsons’s position. Next to Luis Alvarez, Parsons knew more technical details about how “the gadget” worked than anyone on the runway.11

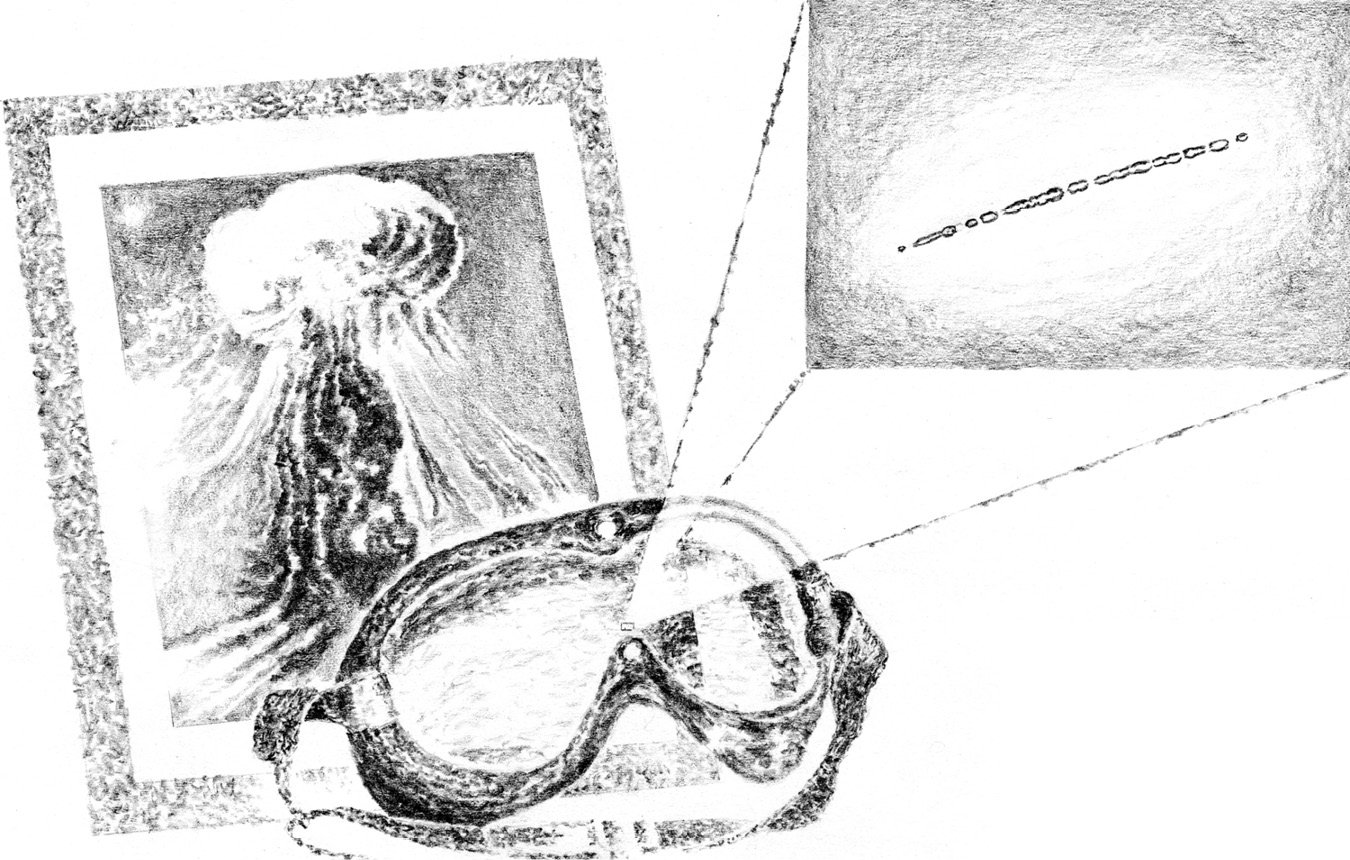

Russell Gackensbach did not take Tibbets’s offer. If Luis Alvarez carried one of the deadly pills with him aboard the Great Artiste, no one noticed and he decided never to speak of it. Gackensbach and Corliss had been kept in the dark about what their team was carrying; so, probably, there was no need to offer them pills—only dark goggles, with instructions to put them on when their captain gave the order, about three minutes out from the target.12 They were not to look at the source of light.13

Parsons, who had been present at the Alamogordo test of a tower-mounted plutonium version of the weapon they were about to deliver, had told them that this new species of fire bomb was “the brightest and hottest thing on this Earth since creation.” He warned that a soldier standing more than five miles away from the test firing was temporarily blinded by the flash. Parsons never mentioned atoms or kilotons, though he knew Alamogordo’s artificial sun had unleashed almost 22 kilotons of energy—exceeding Enola Gay’s device by about 10 to 12 kilotons.

Some of the crew relied on earlier assumptions that what they were about to deliver was a new nightmare dreamed up by the chemists. A few suspected a physicist’s nightmare. Fewer knew for sure.

Gackensbach’s and Corliss’s plane was number 91, flown by Captain George Marquardt. The plane had all of Runway C to herself. Runway B held Captain Sweeney’s still uninscribed Great Artiste. The next runway over, “A,” was the center of some sort of commotion. Flashbulbs were igniting again—all around Paul Tibbets and Enola Gay. His was the only plane in the trio with a name painted behind its nose. Tibbets had named her after his mother. All any of the photographers knew about the plane was that Tibbets would be carrying “something special.” If he came back, they would know the rest later.

After George Marquardt and the ground crew finished their walk-around of Number 91—Necessary Evil—searching for minute stress fractures or signs of leaking hydraulics, James Corliss followed Marquardt up through the hatch of 91’s nose wheel well, and took his position in the flight engineer’s seat, located behind the co-pilot on the plane’s starboard side, and above the bombardier. Russell Gackensbach took the navigator’s position on the port side. The B-29, though spacious by comparison to Gackensbach’s previous experience on the B-17s, was still a cramped ship. If he wanted to, he could easily have reached across from port to starboard and shaken hands with Corliss.

On Runway A, Paul Tibbets started the atomic strike plane Enola Gay’s run at 2:45 a.m. Three minutes later, Charles Sweeney flew Alvarez’s scientific escort plane Great Artiste off Runway B; and three minutes after that, George Marquardt followed in the photographic escort plane, Necessary Evil. The three planes remained staggered at sixteen kilometer intervals throughout their three-hour flight to their first rendezvous point.14 Thirteen minutes out from Tinian, while flying only at 4,600 feet, Parsons descended into Enola Gay’s unpressurized bomb bay and began inserting the cordite charges into the bomb, following the detailed checklist he had written during his practice sessions, and keeping Tibbets informed through an intercom link of his progress on the arming procedure.15 Aboard the other two planes, members of the scientific team closed their eyes and attempted to take naps, reserving their energy for the business end of the mission.16

At 5:45 a.m., Gackensbach and Corliss became aware of a familiar banking motion, indicating that the time of rendezvous had arrived. From the starboard side, Corliss could see the red hull of the sun emerging on the horizon. Directly below, the captured runways of Iwo Jima spread out before Mount Suribachi—already sanctuary for hundreds of B-29 crews returning from fire-bombings with half-crippled aircraft. Sweeney and Marquardt drew in behind each of Tibbets’s wings, circled Iwo with him, and set course for Japan.

Two hours later, Claude Eartherly’s advance scout plane, Straight Flush, triggered a brief air raid alert throughout Hiroshima while conducting weather reconnaissance. Because radar and ground observers judged the plane, correctly, to be just another flyover by a lone observer—just like dozens of previous photo-recon flights—the alert was called off with an all-clear siren. The city’s defenses quickly returned to their usual stand-by status—just as Luis Alvarez and Paul Tibbets had planned. The scout crews did not know as yet that one function of their previous Hiroshima flybys was to lull the target into a sense that flyovers by one or two B-29 “strays” without fighter escort were commonplace and, presumably, mostly harmless.

The tactic was cold and mathematical, cheerless and logical. Because “the gadget’s” interior geometry needed to be machined so precisely that a single whack with a large hammer could knock the pieces out of line and degrade or disarm it, the idea of lulling ground-based flak gunners and fuel-poor fighter pilots into complacency was judged to be a “best defense.” As Sweeney saw it, induced complacency reduced the probability that a bullet or a piece of shrapnel would pierce the plane’s hull and “pooch” the bomb’s delicate geometry. To Charles Sweeney, every one of the “harmless” flybys leading up to this day had been directed by the mathematics of probability theory mated to psychology. Cold, he acknowledged to himself. But somewhere along the line, cold math became our new co-pilot. Logically, it had to.

About 7:30 a.m., Straight Flush sent out a coded message: “C-1”—which translated as, “Clear weather, primary target.” At that moment, Tibbets’s three planes were crossing over from the ocean to the mainland of Japan, while ascending to their bombing altitude of nine kilometers. Parsons was out of the freezing bomb bay, with the pressurized hatch sealed behind him and the device below now fully operational. Everything was proceeding as Tibbets had promised: The mission for which they had been training was going to be completely different. Fire-bombers usually cruised at only one-fifth this altitude.

Three minutes from the Aioi Bridge, Captain Marquardt ordered his crew to put on the goggles. Before their world went dark, Gackensbach’s and Corliss’s instrument readings were nominal; and according to the view through Necessary Evil’s forward dome, no one was sending up flak bursts. Nor, it seemed, were enemy planes being scrambled to intercept Tibbets’s three “strays.” As a handicap, the darkness of the goggles did not particularly worry the navigator or the flight engineer. Whatever the purpose of this strange mission, it appeared that no one and nothing was going to interfere.17

According to plan, Marquardt’s plane banked to one side and fell two miles behind Enola Gay and the Great Artiste.18 In the tail section, Professor Bernard Waldman prepared to fire the trigger on his high-speed camera, designed to capture the first fifteen seconds of the detonation in ultra-slow motion.19

Ahead of Necessary Evil, aboard the Great Artiste, Kermit Beahan and Luis Alvarez waited for their signal to open the bomb bay doors and release the three parachute-equipped scientific instrument cylinders. The mission profile called for Enola Gay and the Great Artiste to drop their packages at precisely the same second. The bomb would free-fall to an altitude of just under 579 meters (1,900 feet) before detonating, with the instruments deploying their chutes about twenty seconds earlier and 12,000 feet higher. The mirror-like canister surfaces and pure white chutes would, it was hoped, resist the flash effects and give the transmitters a second or two more of life before they were overcome by plasma and blast.

The two leading planes would not be much farther away than the canisters. They were moving into a realm of total uncertainty. No one had ever tried flying away from a nuclear blast before, yet if unprecedented risk was the price of throwing open the doors to a nuclear frontier, then the planes and their crews would be expendable.

Planning for the worst, and hoping for the best, Beahan’s and Alvarez’s captain was placing his bets on what he would later call “The Tibbets maneuver,” and what one critic, on first hearing of it, had already labeled “The Bonehead Maneuver.” It required a reversal of course and a crash-dive acceleration—at one point straight toward the ground—during a time frame in which the bomb itself was also falling earthward.

The genesis of the maneuver was a question of simple spatial geometry. During the forty-three seconds between release of the bomb and detonation, how much space could a B-29 put between itself and the bomb so that the B-29 would still be flying in one piece?

Tibbets’s maneuver was a variation on an ancient geometric formula he had learned in junior high school—“A gift from the Babylonians and Egyptians,” he said, ”with which we can calculate the distance from a point on a tangent to a semicircle.” If the plane were traveling at a ground speed of 450 miles per hour (or 727 km/hr) at an altitude of 30,000 feet, then on release the bomb would start out with the same forward momentum as the plane, falling on trajectory toward its target. The last thing in the world any pilot still taking in air and in his right mind wanted to do was what bomber pilots had been trained to do; stay in a tight formation into and away from the target—which amounted to flying in formation with their bombs.

Under the old rules, the Hiroshima formation would have traveled almost 5.5 miles by the time the bomb detonated below them, and barely more than a mile behind. Tibbets saw immediately that if the planes simply shot off perpendicular to the line of trajectory, the bomb’s forward momentum would carry it roughly four miles down-range during the critical forty-three seconds; and if instead of fleeing sideways at a mere 90-degree angle, he dove at the ground for a few seconds and used gravity to accelerate a little bit beyond his fastest cruising speed, while turning in a direction exactly opposite the bomb’s trajectory, he would take the plane more than nine slant miles away from the blast.

The tactic was totally unheard of by pilots Sweeney and Marquardt, and totally brilliant. Aboard Necessary Evil, navigator Russell Gackensbach’s first clue that his world was about to change forever came after Enola Gay radioed a high-pitched warning signal to its companions. Thirty seconds later, at precisely 8:15:15, the signal stopped and four objects dropped simultaneously—one from Enola Gay, and three from Great Artiste.

Gackensbach did not see this; neither did George Marquardt. Before the thirty-second warning, Marquardt had glanced over his shoulder and observed Hiroshima lying peacefully within the braided outlines of its seven rivers, during what would be burned into his memory as one of the most beautiful, clear, and sunny mornings he had ever seen, mingled with the realization that it could not last.

Somewhere within Necessary Evil’s radius from the target point, Luis Alvarez was presently being squeezed into his seat by Sweeney’s execution of the Tibbets maneuver. Sweeney discovered, to his growing discomfort, that the dark goggles made it impossible to read his instruments, or even to properly gauge how close his escape dive was bringing him to the ground. All that mattered now was being able to see clearly, so he shoved the goggles up to the top of his forehead, regarding any impending flash-damage to his eyesight of only secondary concern. More than two miles beyond Sweeney and Alvarez, Gackensbach and Corliss were being pressed into their seats by an only marginally less extreme version of the same peel-away and run maneuver.

The bomb erupted almost nine miles behind Sweeney and Alvarez in the Great Artiste; but to Sweeney, without his goggles it seemed that a thousand suns were bleaching the sky white, directly ahead. The pilot reflexively squeezed his eyes shut, but the light filled his head with pain, while someone in the tail section began yelling gibberish over the intercom.

At a distance almost three miles past Sweeney’s blast radius, Captain Marquardt heard similar inarticulate calls from physicist Bernard Waldman. The men at the tail gunner positions of both the Great Artiste and Necessary Evil were trying to describe phenomena no one had seen before.20

Waldman had aimed Necessary Evil’s high-speed movie camera in the general direction of what would become known to future generations as the Hiroshima Peace Dome. Surrounded by high-strength Plexiglas, the tail gunner’s seat provided an incomparable, 180-degree wrap-around view. Waldman saw exactly how it all began, near the Aioi Bridge. The initial pinpoint of light was so intense that even in full obedience to Alvarez’s warning to cover his eyes, even with both hands cupped tightly over his black goggles during the first three seconds, the light filled his head with a dazzling red glare, as if shining directly through his skull and reaching into his retinas—which, in fact, it was.

When Waldman uncupped his hands, the fireball was already ascending at tremendous speed, dragging behind itself a stem of roiling black dust wrapped in flames. During those first few seconds, Waldman had missed his opportunity to press the trigger at the assigned moment, to make sure the movie camera was aimed in precisely the right direction, and to set the right filters into motion in their proper sequence. The film was off target, mis-timed, and irretrievably damaged.

In the navigator’s seat, Russell Gackensbach aimed his Agfa 620 camera through his window and snapped two photos of the rising plume about a minute after the detonation, as Necessary Evil circled to within twelve miles of Ground Zero. His film had also recorded scores of little white flare spots, the apparent result of exotic particles traveling at a substantial fraction of light-speed, somewhat like cosmic rays—except that in this case, they emanated from below, and not from the sky. Eleven miles nearer than Necessary Evil, about a mile southeast of the hypocenter, X-ray film plates that had survived in a hospital without their protective casings being broken, were nonetheless thoroughly overexposed by the surge of gamma rays, neutron spray, and particles.21

To Gackensbach’s right, flight engineer James Corliss looked on in stunned silence; but he would later write about the mushroom cloud: “All the time it was churning all around, sometimes inside out, with red, yellow, purple, and brown colors.” He knew that down there in the city, or in what remained of it, the vortex must be hoisting cars, buildings, bodies, and dirt into the sky. The initial flash was describable only in the language of silent disbelief. Even behind the protection of dark goggles, Corliss had been forced to squint. The light filled the entire interior of the cabin, like a huge magnesium flash bulb indoors and directly in Corliss’s and Gackensbach’s faces.22 They experienced a slight sunburning of facial skin not covered by the goggles.23

Forward of them, in the cockpit, George Marquardt was now partly blinded by a bright green afterimage, floating in the center of his field of vision. Unlike Sweeney, who was nearer the detonation point and who had removed his goggles but who could now see clearly, vision was returning much more slowly to Necessary Evil’s pilot. The difference lay in the fact that Sweeney had been looking straight ahead along his escape path and almost 160 degrees away from the explosion, while Marquardt had glanced back upon the doomed city during that first split second. Even through the obscuring effects of his dark goggles, Marquardt was able to discern the thick film of black smoke that rose instantly from every tree, rooftop, and wood-framed wall touched by the flash. That quickly, the black fog had covered more than half the city. “Smoke boiled around the flash as it rose,” he would record later. “It seemed as if the Sun had come out of the Earth and exploded.”

Paul Tibbets, Jacob Beser, and other crew aboard two of the Hiroshima mission’s B-29s, reported a taste like molten metal emerging from fillings in their teeth. Examination of plexiglass and the crew’s flash-protective goggle-plates revealed microscopic melt-trails consistent with the cores of metallic atoms passing through the planes at between 30% and 90% light-speed. Under the short-lived magnetic fields of the detonation, certain planes and certain city locations were randomly targeted by something very next-of-kin to Brookhaven National Laboratory’s (modern) Heavy Ion Collider. [Illustration: CRP]

Marquardt and other members of his Necessary Evil crew became aware of a taste like lead in their mouths. More than camera film had been damaged by the particles and the rays. Something from the bomb itself had evidently passed through their teeth and interacted with their fillings. Marquardt began to wonder about the other planes.24 He knew they must have been at least two miles nearer, at Moment Zero.25

At the helm of Enola Gay, Paul Tibbets also became aware of a strange taste. As the flash blazed forth, he heard and felt a crackling in his jaw, and simultaneously came the unpleasant taste, “like an out-flowing of lead.” Pieces of the bomb (quantum artifacts) had embedded in his fillings and passed through his flesh. The pilot would recall later that the light from the bomb seemed to have substance—a light that could be felt, and even tasted.

During that first chip of time, the most destructive particles were fortunately among the rarest. A heavy, positively charged nucleus of iron, tungsten, or uranium from the bomb’s interior, traveling at a substantial fraction of light-speed and following the bomb’s short-lived but extremely powerful magnetic field lines, could pass through Plexiglas and through people, shedding energy as it passed. The heaviest and fastest nuclei could disperse an amount of energy equivalent to the force of a baseball pitch, along a line of destruction only slightly wider than a few red corpuscles lined up side-by-side. Whenever and if ever any of the crew were penetrated by heavy ion collisions, the impactors did more than merely vibrate fillings in teeth. They formed flesh-melting lines of cauterization narrower than a human hair, but reaching all or most of the way through a human body. For several seconds afterward, veins and arteries in the line of fire would have been shooting micro-clots of seared blood in random directions. With all else that was happening in and around the planes, the occasional pin-prick or stinging sensation might not have been noticed at all.26

In the co-pilot’s seat of Enola Gay, as he and Tibbets circled around for a closer look, Captain Robert Lewis noticed that, unlike the successful completion of a standard fire-bombing mission, there were no signs of relief, no cheering.

After an initial moment of amazement that the gadget had worked—“My God, look at that son-of-a-bitch go!” Lewis shouted into radar operator Jacob Beser’s headphones, a moment of disbelief followed, and he whispered, “My God . . .” Beser removed his headphones, climbed aft, and looked down. He could not see the city at all. Something shadowy and strange was moving across the surface of the Earth; it reminded him of what sand at the beach looked like if he stood in two feet of water and stirred up the sand as vigorously as he could until it billowed. He quickly came to terms with the taste of molten metal leaking out through his teeth, but the image of roiling sand in water—with new fires breaking out every second along the periphery of the swirls, was harder to shake off. Beser loved the sea, and though nothing would ever keep him away from sailing on deep water, he could never again go to the beach and wade into the surf, after Hiroshima. Tibbets seemed mesmerized by the view. What had once been distinctive rows of houses looked to him now like fields of boiling black tar.27 He would report later that once Iwo Jima and Okinawa and the kamikaze attacks had prepared his mind for reception of the idea that the entire population of Japan would fight to the death till the very end, the ground-hugging dust and the sparkling debris fields meant to him only that, if this bomb did not end the war, there would at least be fewer of the enemy to contend with during the final invasion of the mainland.28 Presently, he kept the thought to himself, and prepared to cede control of the cockpit to co-pilot Robert Lewis.29 He wanted to go to the back of the plane, where he planned to catch about three hours of sleep during the return to Tinian.30

Miles away, surveying the damage from the navigator’s seat of Necessary Evil, Russell Gackensbach shared the same thought as Tibbets—there are fewer of them now—while Tibbets’s co-pilot came to an altogether different thought, and wrote in his log: “My God, what have we done?”31

One day, relating what he witnessed to his son and grandson, Jacob Beser would refer to Hiroshima and Nagasaki as, “the most bizarre and spectacular two events in the history of man’s inhumanity to man.” Presently, however, he was content to look down and to know, “There are fewer of them.”32

Down there in the swirls of fire and debris, Hiroko Nakamoto was aware of a smell she had never known before—which turned out to be her own flash-burned skin. In the direction she was walking, all the houses seemed to have vanished and the tallest structures were streetcars, filled with bodies. Some of the people were burned so black that it was impossible to tell whether they were lying face-down or on their backs. Indeed, it was difficult to believe they were human beings. Hiroko felt as if the side of her face that was exposed to the flash was now somehow detached, and no longer belonged to her. A woman approaching out of the smoke stared at Hiroko, then turned away with a gasp of horror. Hiroko wondered why.33

In the cockpit of Great Artiste, Charles Sweeney had a less close-up and personal view. After he leveled out from the shockwave, and began circling back, Hiroshima lay to the west, on his starboard side. He looked down and saw a dirty brown stain on the Earth, boiling over the city—spreading out horizontally and without detail. Out of it had emerged a vertical plume that contained every color imaginable, along with colors he had never imagined. Sweeney swore that, impossible as he knew this to be, he was seeing colors that simply did not exist in the electromagnetic spectrum—new colors, never before seen by human eyes. He circled once, so that the scientists could film the cloud, but much of the camera equipment and the film inside had been damaged. The plume towered more than three miles overhead and was still growing when the B-29s turned back toward Tinian Island. They were nearly a half hour and 200 miles away from Hiroshima before the tail gunners began losing sight of the mushroom cloud.34

Far behind the Tibbets planes, in Tokyo, Dr. Yoshio Nishina and Eizo Tajima were already trying to convince War Minister Anami that the sudden, simultaneous cessation of all radio and telephone communication from Hiroshima was consistent with an atomic bomb. Even after Prefect Nishioka managed to patch a line through from the suburbs, and to confirm Dr. Nishina’s assessment with his own eyewitness account, Anami would not believe it. Even after the American president broke the secret to the whole world many hours later—“The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base”—the war minister refused to accept it.

Just the same, he decided that it would only be sound logic to discover what captive American airmen knew about their country’s atomic bomb program. Anami was working under the dual certainty that everyone talked under torture and that the American program was as open a secret as Dr. Nishina’s program. The second “fact” was a myth. However, Tibbets and Parsons had been aware from the start that the first fact was true, and for this reason they carried already loaded sidearms during their mission—not for self-defense in the event of imminent capture but for self-silencing, just in case the cyanide failed.35

The first pilots questioned by the Japan War Ministry died without revealing anything. Anami was beginning to suspect that perhaps they really did know nothing at all—which enabled him to latch on to hope that the atomic bomb might not exist—until, after nearly twenty-four hours, the interrogators brought in Lieutenant Marcus McDilda, a fighter pilot who had been downed near Osaka. Marcus knew nothing about uranium or initiators, but as near as he could tell, his interrogators seemed to have uranium on the brain, and they were telling him much more than he knew. Being a pilot, what he already did know, very well, were the mathematics of spatial geometry. Meanwhile, his interrogators already possessed one of the uranium bomb’s biggest secrets: the business end of the bomb was all about spatial geometry—and childishly simple. Given enough of the highly refined neutron-emitting metal, there were many ways of skinning this particular mathematical cat; the truly difficult part was designing a bomb that would not surge when you did not want it to surge.

After a general pierced Marcus’s lower lip with a sword and displayed for him the severed head of an airman who had “pretended” to know nothing about uranium, the pilot began designing a totally imaginary atomic bomb on short notice—having no real idea what he was doing but, rather, making it all up as he went along. Marcus described two uranium spheres separated at opposite ends of a lead shield, inside a bomb-shaped box small enough to fit inside a single B-29’s fuselage. When the bomb was dropped from the plane, the shield was removed and two steel pedestals slammed the uranium spheres implosively together.

The general stood back, awestruck. What the airman described was consistent with an early version of the Nishina-Sagane design.

Marcus sensed that something unprecedented had just occurred. He had never heard of a prisoner striking fear into a Japanese interrogator.

“What is the next target?” the general demanded.

Marcus grinned and spat blood. “Right here!” he said. “Tokyo will be bombed in the next few days.36 We’re bringing it right down your throats!”37

On the evening of August 7, as the interrogations began, as Hiroko Nakamoto found safety among relatives in the suburbs, and as Kenshi Hirata tossed a flower into a Hiroshima river and prepared to carry his wife’s bones to Nagasaki, War Minister Anami assigned a pair of planes to Dr. Nishina and Lieutenant-General Seizo Arisue, with instructions to land in Hiroshima the next day and determine whether or not the bomb was indeed atomic.38

Ahead of them, dozens of American planes had already returned from Tinian for the first photographic reconnaissance of the ruins. The scouting sorties reported that over most of the city, only the physical geography remained recognizable—appearing much as it would have seemed ten thousand years ago, before city builders came to the river’s edge. A few of the bridges were still there; but they were broken and “bleached out;” and during those first days the shadow people on the Aioi “T” Bridge were much more distinct than they would appear to latecomers, two or three months after the first strong rains. In the middle of the “Flatland” known to the scientists as Ground Zero, the Dome and some of the municipal buildings and the telephone poles that surrounded them were still standing—and, farther off, reconnaissance experts were shocked to see the partly intact frame of a church.

Far beyond the church, amid a stand of mauled and dislodged buildings, Tsutomu Yamaguchi boarded the second-to-last train to Nagasaki. He had developed a high fever and was suffering continually from dry heaves. There was no longer anything left in him to be vomiting up. By now he had discovered to his growing horror that he could not even keep down small sips of water, and thirst was tearing at his throat.

Prefect Takejiro Nishioka was aboard the same train, his only symptoms of radiation sickness a stinging and itching sensation in his legs, which he attributed to the strange “candle garden” through which he now wished he had never walked.39

Engineer Akira Iwanaga was also aboard—thirsty and fending off mild bouts of nausea.40

All three men were destined to become double atomic bomb survivors.41 A fourth passenger, Dr. Susumu Tsunoo, dean of the Nagasaki Medical College, would meet a somewhat different destiny. He had escaped from the first bomb with scarcely a scratch, and was showing no symptoms at all of radiation sickness—yet, in less than forty-eight hours, he would be running an errand to a district about to disappear from history.42

On Tinian, now that his own eyes and President Truman’s announcement had rendered the weapon no longer a secret, Russell Gackensbach and virtually every other serviceman began keeping, as souvenirs, samples from the many thousands of leaflets that had been dropped over Japan by the recon planes, urging evacuation and “an honorable surrender” and warning about the accuracy of President Truman’s statement—that the power now existed to completely destroy Japan’s power to make a war.

On one side of each bill-sized leaflet was printed a perfect counterfeit of Japanese currency; on the reverse, the message. Aware that civilians picking up and reading the leaflets might be punished by military police, they were disguised as currency to make concealment and private reading easier. It seemed inexplicable to pilot Charles Sweeney that in response to the bomb and to the president’s message, and to the leaflets, there came only a desert of silence from Tokyo.

As the sun set on Hiroshima and Tinian, Curtis LeMay ordered 152 B-29s aloft, to inflict conventional fire-bombings upon Japan.

The night of August 7 came and went, and still no response came from Tokyo.

As the dawn of August 8 approached Tinian, Charles Sweeney was called to the Intelligence hut. According to reconnaissance photographs, Hiroshima’s activities as an industrial base had ceased. Preliminary casualty estimates were approaching 100,000 people.

Sweeney walked over to the air-conditioned compartment, called “the shed,” and put his hands upon the hull of the plutonium bomb. Several of his fellow officers had already signed their names on its yellow-painted surface. Sweeney knew that plutonium emitted constant streams of alpha particles. The bomb’s casing was warm to the touch—“as if it were a living thing,” he would tell future historians.

The shape of things to come, Sweeney told himself. Luis Alvarez had just explained to him that this bomb was only a firecracker, compared to what would soon be on the drawing boards. Dr. Alvarez enthusiastically quoted a friend named Harold Urey, who had declared, “When humanity sees what science has done, they will see immediately that here is the end of war.”

Sweeney did not believe that scientists understood humanity very well. “Still no word from Japan, I presume?” he asked.

“No,” said the scientist. “It looks like we’re going to have to do this again.”

“Understood,” Sweeney said, and walked out of the shed without saying anything more. He borrowed a Jeep and drove away from his own bombardment wing, the 509th, and toward the 313th. Captain Downey, the chaplain who had given the three Hiroshima crews a blessing on the morning of August 6, was a Lutheran. A priest, Father Zabelka, had also attended the blessing. Sweeney was a Catholic. He needed to find the priest.43