With the survivors now accustomed to mass pyres, a curious calm settled over Hiroshima. The normal human responses to roving black fogbanks of corpse-fed flies were completely dulled. On August 10, the boy who would write the Barefoot Gen chronicles no longer felt able to react with excitement or fear, even when he beheld a river delta so glutted with disintegrating bodies that from that day forward, whenever low tides came to the mudflats, the earth itself would appear to be sprouting fields of twig-like rib bones.

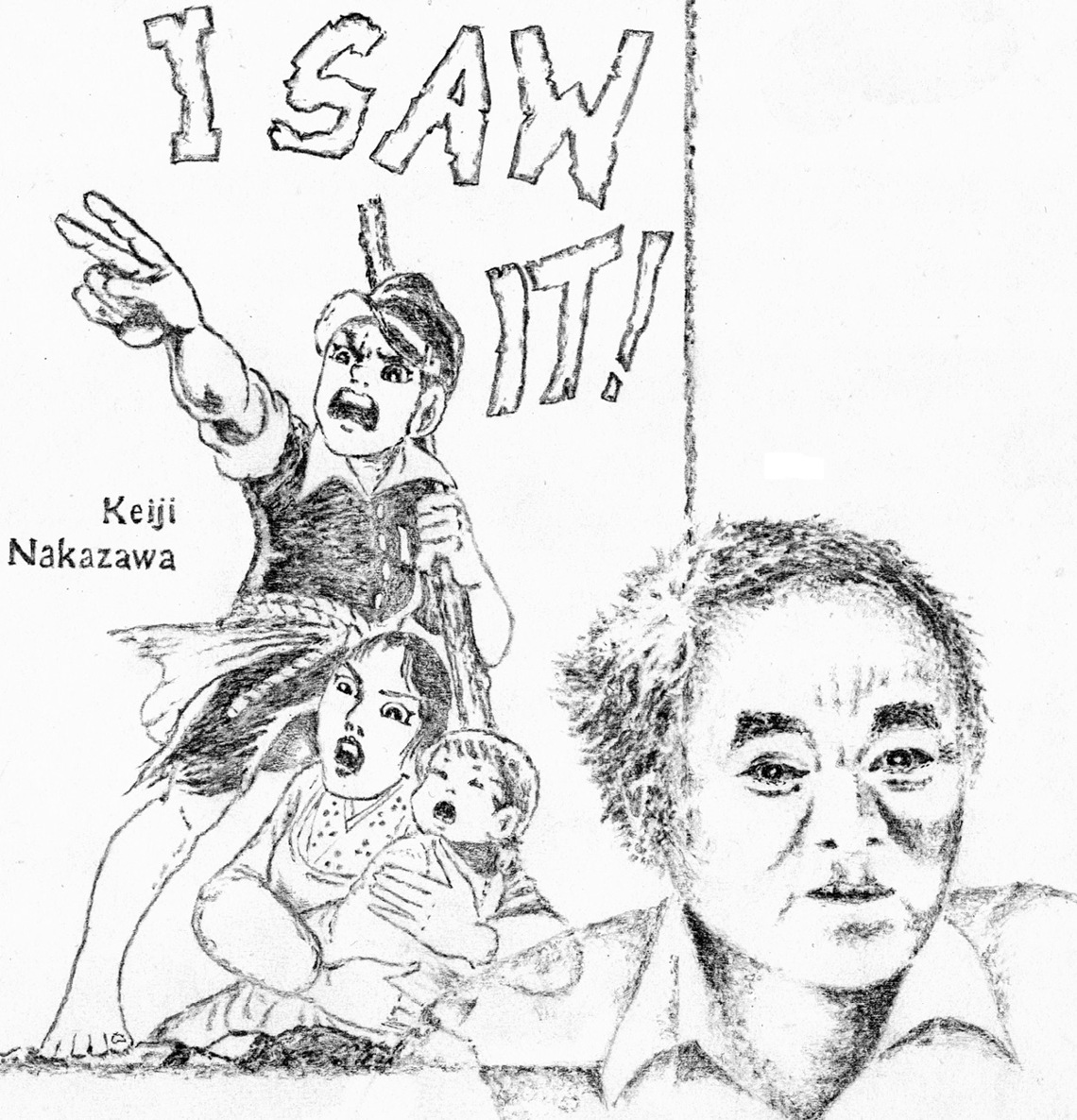

For years to come, Keiji Nakazawa would not speak of what he had witnessed or how he responded to it. He had no choice. Soon, the MacArthur protocol would prevent anyone from speaking too loudly. And beyond official censorship, Nakazawa was governed by an old schoolyard tale about the devil, who was said to have proclaimed, “If we catch a glimpse of hell and speak of it, we are pulled back again to hell.”

Only much later would Nakazawa reply to the devil’s proclamation, telling all who would listen that if everyone remained silent and allowed hell to be forgotten, then hell would be all but guaranteed to come again.

Inside Ground Zero, on the fourth day after the bomb, there was simply no time for either emotion or reflection. Nakazawa spent almost all of the energy he could summon returning to the destroyed fields in search of edible stems and tubers. When thirst overcame him, he sucked the juice and the flesh of dying squash plants. Even if the food he and his brother Koji brought home was half-destroyed and rotting, their mother forced herself to eat it anyway, hoping that she would continue producing milk for the baby.

To provide better shelter for Mother and Tomoko, Keiji Nakazawa and his older brother decided to move from the street-side camp and led the family to a shed at the foot of the hill from which meteorologist Isao Kita had watched the lakes of boiling yellow dust and the streamers of black rain spreading over the city. New families migrating to the weather station hill were resented by people already living in the fringe of the blast area, especially if the newcomers arrived from the heart of the city and exhibited symptoms of Disease-X. Rumors that they carried something infectious from the bomb had spread before them.

“Rumors spread to erase the unease,” Keiji Nakazawa would recall, “and people acted on them.”

Along the path home from one of the fields in which Tsutomu Yamaguchi had received a brief misting of oily black rain, Nakazawa passed through an army rifle range where piles of burning corpses were so numerous that the outdoor crematoria illuminated the night, taking the place of electric lights. The boy continued homeward with one of his small bundles of vegetables, believing that he had become reasonably immune to the new realities, until he saw a woman kneeling on a slab of broken concrete, hammering a charred human skull into fine powder. He paused to watch, and the woman took no notice of him as she gathered up skull powder and sprinkled it over the wounds of a young man lying beneath a makeshift lean-to.

“What a strange thing to do,” Nakazawa said with detached curiosity.

The woman gave him no reply. She lifted the young man’s head, pried open his mouth, and poured in a handful of the powder. The man’s nose appeared to have been bleeding for at least a day or two, and all of his hair had fallen out. Even his eyebrows and eyelashes were gone, and his entire skin surface had been bruised. The mouthful of dust made him cough up a huge clot of blood.

“Excuse me,” Nakazawa said, as politely as he could, “but why are you feeding him powdered bones?”

“Putting this powder on the bruises makes them heal,” she explained with an oddly flat courtesy. “And if you swallow the dust of the pika-man, it keeps you from dying.”

“That can’t be true. It sounds crazy.”

“Stupid!” the woman shouted, no longer either detached or courteous. “Hundreds of people have been saved this way!” Then, noticing that the burn at the back of Nakazawa’s head was oozing yellowish-white matter and appeared not to be healing, she offered him a handful of dust.

“No, thank you,” Nakazawa said, and walked onward. Further along the path, he noticed a second woman, sprinkling dust on two burned children. Throughout the ruins, strange rumors continued to take root. Everyone wants to help their injured [family members] so badly that they’ll believe almost anything, Nakazawa thought; and he wondered who had first come up with the idea that the bones of those touched by the pika could heal people.

He accepted the bone-eaters as just another strange fact of life after the pika-don. Meanwhile, the two Nakazawa boys continued to bring their mother and their baby sister more than repulsive scraps of vegetable matter from the fallout-swept fields. The amounts of residual radiation in the sweet potatoes and their stems were such that if Dr. Nishina or the scientists who designed the bomb’s core ever passed a Geiger counter over the material, their eyes would have widened with alarm and they’d have backed up a few steps. The substances were not overtly lethal. With rubber gloves and other minor precautions they could be safely handled. Yet no one who knew their true nature wanted the soil or the food on his skin or in his body.

Keiji Nakazawa’s mother still had all of her hair and seemed well, but she was already in serious trouble. In years to come, Nakazawa would wonder if there existed a point during the feeding of poison from child to mother and from mother to infant, at which one more dose of radiation was reduced to mere redundancy. He supposed he might just as well ask how many angels could dance on the head of a pin.

While the first-grader’s own symptoms of atomic bomb disease were easily seen, his mother’s symptoms would be hidden in progressive anemia, chronic leukemia, and bone cancer. When eventually she died and was cremated, Keiji Nakazawa would be confronted with the mystery of a body converted entirely to ashes. Already, he had seen enough cremated bodies in Hiroshima to know that the bones, though fragile and easily crushed, still retained their original shape.

“Damn you!” Nakazawa would shout to the bomb itself, to the minds that conceived it and the hands that gave birth to it. Though a coroner would give him many reasons why the skeleton disintegrated, Keiji Nakazawa never doubted that radiation consumed his mother’s very bones; it had continued eating away at her even after she died.

And one evening a cry went out to the impassive stars: “Give them back! Give me back my mother’s bones!”1

On August 10, Takashi Tanemori’s father sent him away from Hiroshima to the country village of Kotachi. During the slow, nearly 100-kilometer journey, aboard what had begun as a standing-room-only train, a seat was finally made available for the boy by the increasingly apparent off-loading, at each successive stop along the sixty-mile trail, of people who had died from flash burns, radiation injury, and festering wounds.

“Daddy” continued searching for the bones of lost family members in and around the hypocenter, eating and drinking whatever he could gather along the fringes of the wasteland.

“Where could he have slept?” the Tanemori child wondered. “Did anyone give him food?” He imagined the echo of Daddy’s voice calling “Yoshiko!” over and over, across a desert where the steel ribbing of the Hiroshima dome had somehow survived, almost directly beneath the bomb.

“While sifting through the ruins,” Tanemori would record later, “my father had no idea he was being exposed to radiation, and the constant exposure began to destroy him. Each time he returned to me, he was more broken and despondent.”2

On the first day of the first bomb, five-year-old Saburo Kobayashi heard his mother cry out, somewhere between the flash and the bursting apart of his grandfather’s home. During the days since, he had never heard his mother’s voice again. He remembered running southward toward the sea, trying to get away from Hiroshima’s waterspouts and fire worms. The road had absorbed the heat from the flash and its surface became like a huge frying pan freshly lifted from a flame. As he ran, Saburo realized that he had fled from the smashed house without his shoes. He alternately ran and walked on scorched feet, leaving the skin of his soles behind. He had been living ever since August 6 in a bomb shelter cave in the side of Hijiyama Hill, behind the ruins of a school.

The cave became what was informally known as “the orphans’ shelter.” Some children, the lucky ones, were found and taken away by relatives who heard rumors about a cave of schoolboys turning feral. One by one Saburo’s companions began disappearing, either because surviving relatives had come searching for them or because, like Saburo, they were weakening and dying. Disease X carried many of them away; and then the soldiers carried their bodies away to the pyres.

“My hair became thinner and its color lighter,” Saburo would record. About the time Tanemori’s father became ill and Nakazawa learned about the bone-eaters, Saburo’s skin developed the star-shaped hemorrhagic spots characteristic of Disease X. “The older boys caught rancids, a type of Japanese frog, and fed them to me, claiming they were tasty when grilled. I was so hungry that these frogs tasted delicious. The days passed and the number of my friends became fewer and fewer. There was not enough food for all of us and before long my body [already skinny from pre-pika don rationing, started to resemble] a skeleton with skin attached.”

By the time the orphans began fighting one another over rancids and other diminishing sources of food, a surviving aunt heard about the cave, and found Saburo.

The boy ran into his aunt’s arms and hugged her, then punched her, crying, “Why couldn’t you come sooner and get me?”

Only after he pushed away from his aunt’s embrace did Saburo notice that one whole side of her face had been scorched by the flash. She begged him to understand that she was unable to move at all until that day, and she promised to adopt him as her own, as a son of the Fujii family.

Among the orphans of the bomb, Saburo joined a lucky minority, taken in by kindly aunts and uncles who had been related only distantly by marriage.3 In most families, a child only distantly related was considered at best an extra mouth to feed during a time of severe food shortages; and a child who no longer had the guidance of a father was generally branded as an outcast who belonged to the streets.4

Nine-year-old Shoso Kawamoto was among the majority of atomic orphans who endured a cruel shunning by his aunts, his uncles, and by the long-standing bias of both Japanese society, and authority, against orphans. After his older sister succumbed to the effects of flash, blast, and radiation, he was left to wander the fringes of Ground Zero, from the Hijiyama cave to the putrid moats near the flattened ruins of Hiroshima Castle. He and the other children were desperate to live, and as the first week passed, they had begun to abandon their parents’ teachings about helping the youngest and the most vulnerable.

Until the first decade of the twenty-first century, Kawamoto would refuse to speak about “how there were so many orphans that we did not have enough food to survive. We were in a constant tug-of-war over food—sometimes for only one dumpling. In the end, the strong survived and the weak died one after another. Those who [eventually] taught me how to live were the Yakuza gangsters.”

The strongest of the orphans would evolve into the next and most powerful generation of the Yakuza syndicate—which would rise out of Hiroshima, driven by a fury against authority that was to be referenced with chilling clarity in Keiji Nakazawa’s crime Manga, Pelted by Black Rain, and echoed in a Ridley Scott film’s disdainful line from a Yakuza crime lord, “You turned our rain black!”

Long after the flash, the blast, and the radioactive rain, Shoso Kawamoto began locking away in his own mind what he witnessed during the rise of the Yakuza. Honor-bound to take names of people, and their actions, with him to the grave, he nonetheless believed that future historians deserved to know something of what came out of Hiroshima. From his deathbed, and referencing his own actions, only, Kawamoto provided a glimpse of how it began for him—“with the atomic orphans’ bitter experiences of being unable to do anything for their dying friends, [and later,] of beating someone for our own survival, rather than out of hatred. However, we will never forget the fact that a person passed away due to the beating.”5

Dust and smoke blew straight across Hiroshima Castle’s foundations and through the Communications Hospital. The sun was almost down to touching the hills now, and even though it still had a way to go before actually reaching the horizon, the smoldering ruins and the funeral pyres and the dust were tinting it gold, almost orange. The lensing effect of the polluted atmosphere gave the ruins a ghost-image aspect, even in broad daylight.

Yoji Matsumoto, a twenty-one-year-old officer returning to the city in search of his regiment, had entered the ruins on August 10, after walking the last thirty kilometers from Saijyo Station, following the railroad tracks down from the hills. The level of devastation he found seemed unthinkable. Except for its stone foundations, Hiroshima Castle was gone. The whole castle—atom bombed. The piles of “ash flakes” and the chilling images burned into stone walls revealed to Yoji the shapes of people turning away from something, or trying to run from it. Pausing to look inside one of the trolley cars still standing on the prairie, the soldier saw a statue man whose tongue and eyelids and fingers were charcoal. After four days, the shock-cocooned corpse had stayed in place holding onto a blackened streetcar strap, and still he seemed to be glancing up at something.

The young officer continued north toward the military base that had stood between Hiroshima Castle and the Communications Hospital. There, in the land between, Yoji discovered that everyone in his regiment appeared to have died instantly.6

That same afternoon of August 10, as the Tanemori boy realized his father might die and leave him an orphan, and as Shoso Kawamoto resolved that he would fight and even kill to live, a woman named Shoda, much like Keiji Nakazawa, seemed to be recovering some of her strength. Her new home was the Communications Hospital’s isolation ward for Disease X sufferers. She was able, at intervals, to rise from her straw mat and breathe in the relatively fresh air outside of the makeshift tent “pavilion.” Dr. Hachiya, the former ant-walker, thought that any improvement among these people was a reason for raised spirits. In his worst nightmares, he had imagined a biological weapon that eventually killed everyone it infected. The report of someone actually making a dramatic recovery now made Hachiya more determined to get out of bed—even if the sutures did pull at his skin. His friend Dr. Hinoi brought a cane and helped him downstairs to the isolation pavilion where the woman lay (not yet recognized by the hospital staff as a well-known poet). On the way down, the two doctors found their eyes drawn constantly toward the hypocenter.

“Aren’t you curious?” Hachiya asked.

“About what?”

“About what’s in there. What does it really look like, up close?”

“I’ve been giving it a lot of thought,” said Hinoi. “I’m not really sure I want to know. And yet . . .”

“And yet, what?”

“I have a bike that still works—and I have to make a visit tomorrow to an army supply barge docked near the gutted bank buildings. I was thinking, perhaps if you’re feeling up to it—”

“Then it’s a deal,” Hachiya said. He would have the stitches removed early in the morning, and after their errand to the supply barge was done, they would mount, by way of detour, an expedition to the hypocenter.

When Hachiya reached the isolation pavilion, with thoughts of exploration and despair vying for first place in his mind, hope came racing toward the finish line in the form of a woman named Shoda whose pulse was strong, whose nose had stopped bleeding, and whose appetite was returning. Shoda returned a weak smile to Hachiya, and for the first time since the pika-don, he felt a sense of what might be called happiness.

Don’t worry, he told himself a moment later, it won’t last. As indeed it could not, once he took his first hard look at the other patients in the pavilion. On first hearing that Shoda’s health had improved enormously and that there were no new deaths to report today, Dr. Hachiya had allowed himself to believe that the worst was over. But when he saw the evidence of fresh bloody urine on virtually every mat, he understood that Hinoi and the other medics were reporting only a fleeting respite.

Two women complained of having chokingly large objects stuck in their throats. Hachiya and Hinoi helped them to cough up golf-ball-sized clots of blood and phlegm. As Shoda looked on, parasitic roundworms came out of their mouths.

Hachiya jumped to his feet, pulling at least two of his stitches.

“I’ve seen this before!” Hinoi said. “But it happens only when people are already dead. Only when the flesh begins to decay and can no longer support them do parasites abandon their hosts.”

Dr. Hachiya glanced over at Shoda and asked Hinoi to move her at once out of the pavilion and into open air. Shoda nodded in grateful agreement. As she stood, one of the dying women emitted a strangled cry and suddenly spat an amazing wad of red phlegm and tiny white worms onto the ground.

“Doctor?” Shoda whispered, trying to keep her gag reflex under control.

“Yes,” Hachiya said.7

“I wonder if there is an operation that removes memories.”8

Near the southern fringe of Urakami’s Ground Zero, ship designer Yamaguchi, his wife, Hisako, and their child were among the few creatures still moving. Though inexplicably (and, he sometimes believed, “miraculously”) alive after two atomic bomb blasts, Mr. Yamaguchi was becoming increasingly lethargic and depressed.

The engineer’s side of his brain told him, logically, to be grateful that his burns from Hiroshima had sent his wife along an improbable path to shelter. Nevertheless, Yamaguchi’s heart told him that his siblings were dead. His cousins were dead. A cousin’s wife and their infant child lay dead in what little remained of “home.”

Hisako’s family had been worse than decimated. Yamaguchi and little Katsutoshi were all she had left, and she began to fear that even this would not last. A tunnel had become their only home, and as Mr. Yamaguchi’s depression grew, his left arm and one whole side of his face had begun to swell like balloons inflating, turning purple and quite painful. The burns on his arms became gangrenous and started sprouting nests of fly larvae, at which point Yamaguchi passed out and could not be roused awake.

Hisako tried to remove the maggots but someone who seemed to know something about medicine arrived at the cave and insisted that she leave the maggots living in her husband’s skin. The idea sounded to Hisako like an old wives’ tale; but she put her faith in the visitor and decided that, even if it was only a myth, if it healed her husband’s burns and he recovered, she would believe in it. She helped the newcomer to feed her semiconscious husband strange new concoctions made from persimmon leaves, dried rose hips, and any other sources of vitamin C that could be found, and she was instructed to cook him helpings of liver from any animal—even from rats, if they could be found. She became convinced, over time, that had she taken Mr. Yamaguchi to one of the woefully overwhelmed and undersupplied first-aid centers near Governor Nagano’s side of central Nagasaki, he would surely have died.

Little by little the blisters stopped discharging blood, and the maggots, hour by hour, removed dead and gangrenous flesh until Hisako believed the bones in her husband’s arms might soon be exposed.

The visitor had sprinkled a powder of crushed grape seeds and talcum on the wounds to dry them out and prevent further infection. He also suggested attaching live leeches to the still-living flesh that surrounded the worst of the burns, explaining to Hisako that leeches would keep blood circulating through her husband’s wounded hands, and prevent his fingers from dying and having to be amputated.

It would all have been dismissed as witchcraft by her ship-designer husband, but he was semi-comatose and now living under the advice of the only house-calling doctor in town, so Hisako obeyed the “witch doctor” and spent uncounted hours searching for leeches and gagging on the bitter mineral water given her by the visitor. The concoction reeked of chalk and something mixed with miso that tasted how iodine smelled. In years to come, Hisako would leave physicians perplexed with assertions that, except for irritability and brief bouts of vomiting, she and the baby did not get sick at all during their stay in a tunnel on the edge of a radioactive no-man’s land. And except for permanent, swelling-induced deafness in one ear, Yamaguchi would make a full and equally perplexing recovery.

The strange visitor Hisako would forever regard as her guardian angel refused her offers of thanks and devotion and, like most true heroes, simply walked away from history’s stage.9

More than twenty-four hours had passed, and yet none of the additional doctors and medical supplies promised by Governor Nagano arrived at or near St. Francis Hospital. After the initial contact over a police radio, about lunchtime the day before, no more news appeared to be coming across the ridge from the governor’s mansion.

When Prefect Nishioka arrived at Nagano’s office, the governor appeared to be walking around in a state of shock. Nishioka learned that Nagano had been existing in a semi-trance state from the moment the initial estimates climbed from 50,000 presumed dead to more than 75,000—with at least another 75,000 severely wounded or near death.

The prefect had struggled for nearly a full day and night through rubble and through a second dose of radiation to cross fields of fallout and reach the governor’s headquarters, only to be immediately upbraided for being late. After this, the governor paced back and forth wordlessly while his chief of foreign affairs yelled in Nishioka’s face about all the staff he and the governor had lost, blaming the prefect for not warning everyone about what he had seen in Hiroshima.

“If I had done as I wished and published a pamphlet about Hiroshima,” Nishioka said in his own defense, “then you fine gentlemen would have been the first to accuse me of spreading wild rumors and I could have been shot for treason.”

“If it were up to me, I’d shoot you now,” Chief Nakamura said, “except for the fact that your hide isn’t worth the cost of the bullet.”

The prefect vomited a thick yellow mouthful of bile at the foreign affairs chief’s feet. Before either man could step back, a second mouthful came up, mixed with blackened speckles of blood.

“What’s wrong with you?” the chief demanded.

“I think we call it atomic poisoning,” the prefect said, and added, “I think I’ll go to my wife, now.”

“You can’t leave!” the governor yelled.

“I’m probably dead already,” Prefect Nishioka announced, and he thought about the black-stained leaves he had observed in the governor’s garden. “Just one last thing, though. Was there a fall of black rain here, yesterday?”

“Yes. And black dust, too.”

“Then I suppose we shall all be in the same boat soon,” the prefect said, and left.10

When Dr. Nagai finally set out from the St. Francis medical outpost, downhill toward his neighborhood, two of his neighbors had already erupted into an argument over a pile of charred human remains, located midway between the foundations of their houses. All the clothing and most of the musculature had been burned away from the body, and a wedding band gave no clues to identify because it was now little more than a melted and re-solidified pool of gold. Each man was shouting that the body was that of his own wife and that he be allowed to take possession of the bones. A third neighbor joined in, pointing out that Mr. Tanaka’s wife had been “kind of heavy set,” and he tried to determine from the diameter of a black stain in the gray ash whether a larger than normal amount of human body fat had been cooked into the ground. He could not tell one way or the other, and for all his knowledge of human anatomy, neither would Dr. Nagai have been able to tell, had he arrived in time to stop the outburst. As he continued his journey downhill, Nagai could only pray that such an argument would not erupt over his beloved Midori.

Less than halfway home, Paul Nagai stumbled and almost passed out. He stood and stumbled a second time, and a little farther downhill he met “old Auntie Matsu,” who kept him from falling a third time and told him, “You don’t want to go down there.”

“Why?”

“Because the people you’ll meet are going crazy,” Auntie Matsu warned. “They are like animals after a forest fire—dangerous and half scared to death, fighting over anything and willing to do petty little bits of evil.”

Leading him back uphill, Auntie described arguments over broken bits of dinnerware turning suddenly bloody, but what seemed to bother her most was an encounter with a young woman who returned home to find her grandmother uninjured and who was singing to herself cheerfully as she washed singed, flower-patterned clothes in black well water and hung them out to dry.

“I’m so happy,” the strange woman had said. “I never thought Grandma and I were such especially good people, but it’s only by God’s special grace that we weren’t killed.” Then, looking out across the center of Urakami, she announced, “Those people who were burned to death—they must have made God angry, mustn’t they? They must have provoked him to wrath.”

“You mean, like my baby cousin Kimiyo?” Auntie Matsu said. It seemed to her that such civilized ideas as “Judge not” and “Love thy neighbor as thyself”—in which Auntie always believed—had been lost and now belonged to an older world.

Dr. Nagai heard that by nightfall of August 10, the strange young woman collapsed and began to suffer nosebleeds. By midnight, she would die very old.11

At dawn of August 11, a wealthy citizen of Nagasaki arrived at St. Francis, bringing fresh white rice for his mother and for a hundred other patients, along with gleeful rumors for Dr. Akizuki—“Doctor, I hear that we have recaptured Okinawa, and dropped America’s own atomic bombs on Washington and New York.”

“Even if it were true,” Akizuki said, “I would never rejoice over that kind of story, I swear it. Hasn’t enough been lost? Is useless reciprocal killing all that we have left?”

The man went home for more supplies, and he would never speak to Dr. Akizuki again about winning a nuclear war.

In the valley below, ten-year-old Sakue Shimohira and her sister finally located their mother. She lay on the ground, carbonized and statuesque. “Together,” Saku would record, “we reached out to the body and said, ‘Mother.’ Before our eyes, [her body] crumbled into ashes.”12

Young Miyuki Broadwater would always remember holding onto her mother’s hand and tagging along as fast as her little legs could carry her through the valley of death. In a manner similar to the strange “ground candles” through which Prefect Nishioka had walked, something near the ground seemed to be simultaneously burning Miyuki’s legs and injecting poison into the skin. Below her knees, the skin would soon be thickening and turning dark brown; and it would remain this way for the rest of her life.

Terrified by what she saw in the bottom of the Urakami Valley, she eventually told historians how people and dogs, horses and cows, were completely burnt, “like charcoals.” More than sixty years later, she remembered her mother holding her hand so tightly that the fingers became numb.

“Don’t look to the side. Keep looking straight ahead!” Miyuki’s mother warned, repeatedly. But she was just a child, and she was curious; so she could not stop herself from looking. She saw her mother pouring water from her canteen into a cup and giving it to a young man whose face appeared to have been thoroughly carbonized on one side all the way down to the skull, with the other half of his face seeming to be entirely normal.

“I have never told anyone about this,” she would record for an archivist in 2010. Miyuki had feared that people would not take kindly to news of what the atomic bombs had done.13 “A part of me wants to talk, but another part of me is afraid that people won’t believe me—that this kind of thing actually happened.”14

Much as no news except that carried by survivors was going out of the two cities, little real information was coming in. At Hiroshima’s Communications Hospital, on the sunny, unusually windy morning of August 11, Dr. Hachiya heard rumors about Admiral Ugaki’s victorious attack on Okinawa before he received confirmation that the earth tremor he felt two mornings before might in fact have been Nagasaki dying.

Dawn had also brought news that more people appeared to be coming down with the mysterious hemorrhagic fever, though this was the first night during which he could report that there were no new or imminent deaths in the isolation tent. Hachiya believed he was beginning to feel the first flu-like symptoms, and wondered if he might now himself be one of the infected.

“I might as well see what’s happened out there before I die,” Hachiya told Dr. Hinoi, and he asked to have all of the remaining stitches removed from his wounds so they could set out on the expedition they had discussed the day before.

“You mean, right now?”

Hachiya nodded.

“Well, and why not?” Hinoi said, and shrugged. “I woke up today with a bit of the gastroenteritis myself . . . if that’s what we’re deciding to call it this morning. We might as well go while we’re still guaranteed to have the strength.”

“Or before the excursion becomes two men on a bicycle with bloody diarrhea,” Hachiya said, and tried to force a laugh. Hinoi stared toward the distant Dome and ignored the joke. He was all business now, mapping the route in his head, revising in accordance to the dictates of roads and debris piles. The path to the army’s medical barge looked simple enough. Their starting point was already within Ground Zero, and buildings tended to be stamped more flatly into the ground here than on the landscape Dr. Nagai had tried to navigate in the hills of Urakami. In central Hiroshima, the streets were clearly visible and in most places seemed not to have been hit from the sides by avalanches of debris.

As Hinoi and Hachiya progressed, the most consistent obstacles they encountered turned out to be downed trolley wires and their supporting cables—which had to be negotiated at regular intervals, two or three times along each city block. These pauses gave Dr. Hachiya opportunities to inspect the ruins on both sides of the road. Most of the buildings had been squashed like wicker baskets stepped on by elephants. Some had burned after they were squashed. Others were simply ground down to pulp and grit. Chips from tile walls and bathtubs were localized in some of the debris piles, indicating where bathrooms had been. Fragments of crockery pointed toward kitchens, and shards distinguished by patterns of finely wrought cloisonné reminded Hachiya when they were passing through a wealthy neighborhood. The occasional burned or broken toy always brought him back to darker realities.

“Damage to the city was far worse than I had imagined,” Dr. Hachiya would record, which said much about what he had seen and touched during the expedition. From atop the Communications Hospital, he had already looked across the hypocenter and had imagined quite a lot.15

One of the largest mansions in town must have been completely carried away by the updrafts and the fire worms; for instead of being hammered into the earth, the house appeared to have been lifted off the ground like a box and hauled away. The first-floor landing of a magnificent oak stairway was deeply charred, but otherwise it still stood perfectly in place with its handrails undisturbed—in the middle of the neighborhood of Komachi, where everything else had disappeared.

Mrs. Nagahashi, a famous musician, had lived in this most modern house in all of Japan, designed by her late husband during a kinder decade, with input from the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. On either side of two grand pianos, built-in cabinets had stood floor to ceiling, bearing an entire library of 78-rpm records.

The westernized house was considered treasonous by most of the neighbors, and in time of war, even the mere playing of music was frowned upon—more so, playing the instruments and songs of the foreigners (or: the enemy). But even during hard times, Mrs. Nagahashi insisted on teaching the neighborhood children how to play the piano. According to her only known surviving student, Chieko Seki, who had been away with her family on the day the pika-don came, Mrs. Nagahashi’s desire to teach music grew noticeably stronger after her son, who once had a promising musical career of his own, was killed during the battles for Saipan, Tinian, and the other outlying islands.

Like the stairway and the two charcoal pianos, everything else on the mansion’s ground floor was somehow still in place, exactly where it had been at 8:15 a.m. on August 6. Behind a mound of small black drum cans that turned out to be stacks of phonograph records fused together, soldiers had found Mrs. Nagahashi in front of a Buddhist altar.16 She looked like a praying mantis—carbonized—and no one who saw the mantis woman could escape the realization that she must have been praying at the moment of the pika.17

When he returned to the Communications Hospital, Dr. Hachiya was too tense to follow Hinoi’s orders and go straight to bed. He resumed something akin to making normal visits to the patients, walking around in a filthy torn shirt, with fresh stitch holes slicked in sweat and grime. He looked and felt like a snail with a beard, and he realized he was beginning to like the feel and smell of his own filth.

Even when night came and exhaustion finally sent him upstairs, all Hachiya could think about were the broken toys—and as the army’s funeral pyres burned under the cold stars, somewhere out there Mrs. Nagahashi still prayed. Dr. Hachiya paced the upper floor of the ruined hospital, paused from time to time to lie down on his bed frame for a few minutes, then paced again. As dawn approached, a great wind began to blow, blotting out Hachiya’s view of the city behind a translucent lens of dust and pyre smoke. The gusts knocked plaster and chips of concrete from the hospital’s few remaining walls.

“This I enjoyed,” Hachiya would later record. “And I seemed to lose all restraint. It suited my mood.”

A new day had begun.18

Michie Hattori, the shock-cocooned Urakami schoolgirl who returned home to discover her whole neighborhood miraculously cocooned behind a tall ridge, was drafted along with her parents and everyone else on her block into the rescue and recovery effort. By the morning of August 12, the effort was reduced mostly to the collection of bodies for a makeshift morgue on the blackened side of the ridge, where they remained beyond sight of the village while Michie and the other children gathered wood for a funeral pyre.

Almost all of the survivors who came from the blackened side were dead within a day or two. With the exception of Michie, the people who walked away from the heart of the blast zone appeared to have been exposed to something that burned them from the inside, and few of these were expected to live for very much longer.

A woman who had survived with the pattern of her kimono tattooed by the pika onto her skin died suddenly after coughing up what appeared to be part of her stomach. An army officer assigned Michie and several other schoolgirls to stack the bodies on the wood pile. Maruta, he had called the corpses—referring equally to the timbers and the dead people as “logs.” And as the skin of a maruta woman tore off in Michie’s hands, and as the flames were finally ignited and huge clouds of flies swarmed around the hot perimeter, Michie could scarcely believe that only a week before, she would have been horrified by a paper cut on her finger.

Less than an hour’s walk uphill and to the northwest of Michie’s town, the world seemed even more wretched to Dr. Akizuki. He glanced reproachfully at the sun; for it had risen as if nothing at all untoward were happening down here on Earth. Its serenity seemed only to intensify his gloom.

The governor’s promise that an army “medical patrol” would arrive bringing supplies and relief had finally been carried out—three days late and accomplishing little more than to inoculate Drs. Akizuki and Nagai against hopefulness. Just when they began to think it was safe to suppose their situation had bottomed out and could not get much worse, something always seemed to sneak up from behind with the message that neither of them quite understood how deep the bottom could be.

Paul Nagai’s aunt Matsu had warned everyone about troglodytes in the lower hills who appeared to be losing their minds. Now Akizuki and Nagai believed they were in danger of losing theirs.

The army medical patrol trucks dropped off more than a hundred additional burn victims whose gums had started bleeding, as well as their noses and bowels. Some were actually weeping blood. The patrol leader said, “They’re losing blood like this because they must have breathed some poisonous gas. They are also sick to their stomachs. Find out what’s causing it.”

“All of our equipment is destroyed,” Akizuki explained. “We do not have a single microscope still working. How are we supposed to discover what is causing the symptoms, much less to cure them?”

“You’re doctors, aren’t you? It’s your job,” the leader said, then helped himself and his crew to more than half of the medical outpost’s boiled and potted drinking water, in addition to much of the remaining food supply.

If not for the fact that Dr. Yoshioka and the other patients needed him, and if not for knowing that it would have been the immediate death of him, Akizuki believed he possessed enough anger-fed strength to decapitate the army’s local group leader with a single swipe of a shovel.19

After the patrol left, Akizuki agreed with Dr. Nagai to give himself precisely five minutes to seethe with hatred and fear, and then to dust himself off and accomplish with what few supplies remained whatever he could, until he could not.20

And so, with barely more than a few pounds of gauze and a bottle of iodine, he set off on his rounds, while the nurses and medical students grew progressively weaker and one by one became patients themselves. In a seemingly opposite and equal reaction, some of the patients became nurses and interns.

Mysteriously, most of the mild, pre-pika TB cases were feeling well enough to assist Akizuki and Nagai in their grueling schedules. Like the previously ailing Dr. Nagai, their health seemed actually to be improving, albeit by small steps. Akizuki noticed that those TB patients who had been particularly heavy smokers also seemed to be more resilient against Disease X. He chalked it up to a Darwinian natural selection effect: were their bodies not built especially well in the first place, they probably would not have survived TB long enough to see the pika-don.

In the afternoon, using a rice steamer as a sterilizing apparatus, using unraveled silk threads for stitches and two TB patients for assistants, Dr. Akizuki converted a burned-out library into an operating room and tried his best to repair Dr. Yoshioka’s face. He found new pieces of glass coming to the skin surface between her cheek and the bridge of her nose—and another close to her eye.

The blast wave had struck the windows almost horizontally, and two or three particularly fast slivers evidently went all the way through Dr. Yoshioka’s cheeks, burying themselves inside her tongue. Another shard had penetrated her blouse and her chest, embedding itself in a rib. He removed it with a dull knife and tweezers, while one of the patients held a candle and a broken mirror to provide something approximating a close-up lighting system.

In total, Dr. Akizuki managed to extract seven pieces of glass over the course of an hour, at which point Dr. Yoshioka could endure the pain and exhaustion no more. He stitched a gash through a breast and another between an eye and the bridge of her nose. The laceration through Yoshioka’s upper lip yawned so wide that the assistants could not bear to watch. A large sliver of glass still remained in her lower jaw, overlooked. Glass shrapnel was particularly cruel, for even had the hospital’s X-ray machine remained functional, glass would not have shown up on the films the way metal shrapnel revealed itself and would have eluded detection.

Early the next morning, those patients who were feeling able—among them the recovering TB cases—began wandering down toward the deeper, flatter ruins: first in search of their loved ones, and then in search of useful implements that might have survived. By now there were few thoughts of rescue in lower Urakami. Theirs was strictly a recovery operation.

Those who were able to find anything reminiscent of their exploded and carbonized homes turned over every fragment of roof tile—though when they reported to Dr. Akizuki what they had found, it seemed only by an act of imagination that any of them could have believed they uncovered their actual homes. All of the roof tiles in the realm of the fire mountain were broken into fragments smaller than hen’s eggs. Most were heavily granulated and pitted by the pika and the fires. As Akizuki recorded it, once the roof fragments were pushed aside, the searchers descended into narrow strata of wall plaster and ashes, sometimes studded with fragments of bone. Though most of the radiation had by now dissipated, what fractionally remained still carried a substantial jolt, especially for people already dosed to varying degrees, and especially in the area around the hypocenter.

By 2008, new construction at Urakami’s Peace Park accidentally revealed an archaeological transect into the hypocenter. Descending through a crevice in time, researchers unearthed a flash-fossilized anthology of mid-20th-century civilization: coins and unidentified bits of metal that had glowed white hot, part of a soup bowl, a comb, two belt buckles, a wire-cutting tool, and sheathed in a residue of decayed isotopes, the carbonized fragments of a human hand. The temperatures here were comparable to the thermal shock effects seen in Pompeii’s sister city of Herculaneum—where, at “only” 5 times the boiling point of water and within 1/20th second, vaporizing blood and brain matter exploded human skulls from the inside. [Illustration: CRP]

Those TB patients who had felt well on the third day and who did not have relatives missing near the hypocenter continued to regain their health. Those who descended into the foothills in search of loved ones returned with radioactive dust on their skin, and in their lungs—which began to work in concert with the usual shocks to the immune system that accompanied the inhalation of alkaline concrete dust.21

In his medical reports, Dr. Akizuki was eventually to call the Urakami dust “death sand.” That night, however, neither Akizuki nor anyone else at or near the St. Francis Hospital campsite had any idea of a new danger that could neither be seen nor felt. Only much later would it be known to them that breezes coming up the hill brought radioactive particles as well as relief from heat and humidity. Only much later would Drs. Akizuki and Nagai understand that the returning searchers who distributed boiled rice to the patients through the nights of August 12 and 13 were already sick men. As they served dinner, their clothes shed “death sand” the way cats shed dander and hair.22 The radioactive particles mixed impartially with diced pumpkins and apples—which the searchers stirred into everyone’s miso soup.23

On Tinian, Charles Sweeney had seen the promising news of August 10 come and go with no word of the indicated surrender offer from Japan actually coming through. The moratorium against bombing with anything worse than leaflets with the harsh writing of Clavell and Michener had continued through the nights of August 11 and 12 and through the afternoon of Dr. Akizuki’s searchers from the TB ward.

In Washington, no one knew, yet, how a deadlock in Tokyo had degenerated into a Palace revolt. On the evening of August 13, President Truman authorized General George Marshall to resume fire-bombings against Japan. During the predawn hours of August 14, Marshall ordered essentially the launch of every one of the more than 2,500 aircraft within striking range of Japan, including some 2,000 B-29 bombers. Two atomic strike bombers and their scientific instrument plane were held back, because they might be needed if further atomic bomb missions became necessary, and feasible, in September and October. Sweeney headed back aboard Straight Flush, flying “as though we were on a milk run,” what was, in all essentials except a working core, the third atomic bomb-run on Japan.

Like Enola Gay and BocksCar, Straight Flush had been modified to carry a single, pumpkin-shaped bomb loaded with a multi-ton explosive charge of Torpex (with a slightly reconfigured detonation sequence, designed to produce a pre-shaped blast ring capable of cutting through anything located on ground level). On this flight, the crews were honing the skills acquired during the previous two atomic bomb runs. The Straight Flush pumpkin was the most powerful non-nuclear explosive ever dropped from a plane, but as Sweeney would recall, though it possessed exactly the same casing and machinery he had dropped over Urakami, “This time, it contained neither the secrets nor the horrors of the universe.”

Straight Flush’s target was the Toyota Motor Works at Koromo. No flak came up and no fighters—and, though Straight Flush was reportedly among the last of the 2,000 B-29s to release its load, this time no smoke from preceding raids obscured the target. Sweeney’s bombardier reported that the “pumpkin” detonated within 200 feet of its aiming point; and the pilot concluded, much as he had concluded after eliminating the Mitsubishi factories in Hiroshima and along the Urakami River, that now Toyota could be added to Mitsubishi as a brand name that had been erased from history forever.24

In Hiroshima, Dr. Hachiya’s morning rounds were interrupted by air-raid alarms from the river barges. In everyone’s mind was the same thought: Could the pika come again, after all that we have been through? The August 6 flash had caught everyone completely by surprise. Hachiya realized that he was now shaking with fear, and as the drone of B-29 engines descended upon the wasteland, he sought the protection of a broad, steel-reinforced concrete pillar. A large squadron was approaching Hiroshima Bay from the south. At any instant, the physician expected another great flash overhead. But he cut short his own feelings of panic and made a decision that if death were to strike this hospital again, then his final moment would be with the patients, and not cringing behind a pillar.

The planes—at least two whole squadrons of them, one after another—passed noisily overhead without dropping anything. Then, suddenly, tremors began coming through the hospital’s floor, and seconds later Hachiya could hear the distinctive distant detonations from stream after stream of blockbuster bombs carpeting the ground in the west. He concluded that the planes must be targeting the naval air base at Iwakuni.

At first, Hachiya felt extremely lucky to have been spared a second time, but it occurred to him that luck had nothing to do with it. There was simply nothing left in Hiroshima worth bombing. With a surge of anger, the doctor understood that his city was merely a detour along which damage wrought by the new weapon could be gloated over from on high.

In a makeshift shelter beyond the hospital, Keiji Nakazawa’s baby sister had ceased crying and, strangest of all, had begun refusing her mother’s milk. As Nakazawa would recall it, “Little Tomoko seemed to be quietly sleeping all the time—a baby ominously too well behaved.”

Not even the squadrons clamoring overhead and the subsequent shaking of the earth roused Tomoko to cries of alarm. When he saw the B-29s, the Nakazawa boy did not think about another pika. He raised a clenched fist at them—realizing, like Hachiya, that the airmen came to gloat. There had been rumors from the outside about defeat, and about inevitable surrender.

“Tell me why now, this talk of surrender?” his mother had said. “Why not before?”

Less than a kilometer away, a thirty-two-year-old poet named Kurihara was asking the same questions as she carried from the foundations of her home a radioactive memento of human bone fragments stuck together like candies in melted glass. One day, she resolved, the memento should be displayed in a museum, where all humanity could come and witness its destiny, and vow to avoid it.

The bones in the glass had been flash-fossilized so quickly that some of them were still white. Kurihara was now adding frightening quantities of her own blood to the memento, from a nosebleed that seemed to be worsening each passing hour.

Somehow, her blood seemed apt. She thought of the Emperor’s red and white flag—which up to now had represented the Rising Sun. But presently, the red of the Rising Sun became people’s blood, and its background of white became people’s bones.

“The people have spilled their blood and exposed their bones,” Kurihara would say later, raising her own clenched fist against the sky—“because of the flag of blood and bones.”25

In Tokyo, Foreign Minister Togo received reconnaissance reports that the United States fleet was gathering, lurking not very far behind the bombers. The Empire’s spotter planes had evidently been allowed to observe the fleet and return without being fired upon. What they reported was not merely a fleet but an armada that seemed to put the record-breaking Normandy invasion in the minor leagues: supply ships of every size and configuration, destroyers, cruisers of indescribable variety, and several aircraft carriers.26 The ships were grouped in formations five across and twenty deep.27

War Minister Anami refused to believe that the armada meant defeat and, along with Field Marshal Hata, General Shizuichi Tanaka, and a major named Hatanaka, he insisted that an all-out bombing raid on the convoy “might make the Americans rethink their actions.” They amazed Togo, speaking as if none of them had attended the Imperial conference on August 9, as if even were their heads chopped off and lying upon the floor, they would somehow be able to bite the toes of their enemies and continue to fight.

A general named Mori was ordered by Hatanaka to join him in sealing the Palace grounds and preventing the broadcast of Emperor Hirohito’s declaration of surrender. When Mori refused, he and his aide were shot and hacked to pieces. Major Hatanaka next conspired to seize control of the nation’s radio studios, hoping to replace the Emperor’s pre-recorded broadcast with an announcement of his own. Hatanaka still regarded the Emperor as a sacred figure who could not be harmed, but everyone else was fair game.

Meanwhile, General Tanaka and his staff received and compiled reports of air raids that appeared to be taking place virtually everywhere. By lunchtime, the general had confirmed to his own satisfaction that the approaching armada—which Anami insisted on dismissing as “only a phantom fleet of rumors”—did indeed exist and was slowly, surely, preparing to take aim directly at Tokyo. At this point, Tanaka withdrew his support for the military coup, and Hatanaka, joined by several other leading rebels, ended his life by suicide on the Palace lawn.

Throughout the long spasm of deadlock and a failed rebellion, any member of the Emperor’s staff could be marked for summary execution and Hirohito himself was, in effect, held under house arrest.

Unable to locate and destroy either of the Emperor’s two recorded declarations of the surrender, and with generals loyal to Hirohito regaining control of Tokyo’s radio stations, Anami wrote, “I apologize to the Emperor for my great crime,” and wandered off to write his last poems, get drunk, and slit his stomach open with a ceremonial blade. Many years would pass before the people of Japan learned what had actually transpired as the morning of August 14 dissolved into an incomparable last gasp of denial, assassination, and suicide.28 But rumors hatched and took flight everywhere—and about everything.29

Kazushige was not yet born on the day Hiroshima died. As his father would tell it, Kazushige’s twelve-year-old uncle Hiroshi had emerged perfectly unharmed from a school on the fringe of Ground Zero, where almost everyone else had been burned and crushed. He was rumored to be a “miracle boy,” and a sign of glad tidings.

Following a set of railroad tracks homeward to the eastern hill country, the Ito boy was helped by a stranger who offered his own rice ration, and whose actions matched Prefect Nishioka’s description of an encounter with a “sole survivor” schoolboy, near a railroad station. By the time the boy returned home, the rest of the Ito family was already counting him among the dead, but he had been so thoroughly shock-cocooned that there was not a scratch anywhere on his body, and even his clothes, though blackened by the rains, seemed perfectly intact.

Locally, he became symbolic of resilience against even the most impossible obstacles.

Kazushige Ito’s father, Tsugio, himself only a boy during the bombs of August, would recall in future years that in the first days following the explosion, his older brother seemed well enough to take him fishing and to participate in a victorious game of baseball against a rival neighborhood team. In reality—and all too often—atomic bomb survivors were not quite as they appeared.

The burning from within started on or about August 14, at the beginning of the Buddhist Week of the Dead. One moment the two Ito brothers were playing, and in the next the older boy fell to his knees, grabbing his stomach as if stabbed. By evening, the stricken child’s mother found it difficult to go near him and began to shrink away from her own son. They all shrank away, because on each exhaled breath, there came a stench that reminded family members of a corpse already lying on the ground for several days. The normal bacteria of decay were eating the Ito child’s lungs and his throat, while his tongue—bloating and purple and hot—stank of rotting meat even as he still moved and tried to speak.

Finally, Tsugio’s brother Hiroshi let out a bone-chilling howl. Foam and blood flecked his lips and, just as suddenly as he had sickened from the “death sand” and the rays, the miracle boy lay back and died.30

Meanwhile, in the blackened shell of Hiroshima’s Communications Hospital, Dr. Hachiya had heard stories about people who were outside a house at the moment of the pika and who were shadowed from the heat ray. And yet, though escaping without any burns, they sickened and died while people who were inside the house, though severely injured by collapsing beams, were still alive. If the rumors about the bomb releasing a poison gas or of the Americans following the bomb with a biological weapon were true, then the people who crawled from inside the house should have been infected or gassed just as easily as those who were standing outside, Hachiya concluded. Whatever killed the people who were standing outside had to involve a very short-lived exposure hazard to something that had largely evaporated by the time the people trapped within pushed their way out to the surface. The more Hachiya thought about it, the more confused he became.

A visit from a navy captain who had come to Hiroshima on a medical barge brought an end to the confusion. “The pika itself appears to be the source of some dreadful disease,” Captain Fujihara explained. “The navy has begun studying more than thirty cases, and though not a doctor myself, I can still tell you without a doubt that in each case, white blood cell counts have been crashing.”

“You’ve got to get me a microscope,” Hachiya said.

“I’m sorry,” the captain replied. “We have only one on the barge and we’re working with a cracked lens.” Apologetically, he opened a briefcase and, instead of medical equipment, presented the doctor with a bottle of whiskey and several packs of cigarettes. “This isn’t much,” he said, “but these things may actually be harder to find than microscopes.”

I’d rather have the microscopes, Hachiya thought of saying, but offered his thanks instead.

After the captain left, Hachiya lit a cigarette and began sifting through the shattered remnants of the hospital’s half-dozen Bausch and Lomb scopes, hoping to cobble together at least one marginally useful piece of equipment. The effort was doomed from the start. Not a single oil emersion lens had survived as anything more than a flattened brass cylinder and glass converted once again to sand. He estimated that the blast wave must have been traveling at a speed of 200 meters—or two city blocks—per second when it struck them.

He remembered that one of the Communications Bureau’s district managers had kept a microscope locked in a safe. The office holding the safe was a bunker, sheathed in reinforced concrete. It made no difference. When Hachiya found the bunker, the whole structure was bent and ruptured like a broken basket. The wind from the bomb had turned the safe completely around and smashed the steel door off its hinges.31 The microscope was so utterly destroyed that the doctor began to appreciate more than ever before the improbability of his own survival on that first day of the pika-don.32

Dr. Hachiya’s second visitor of the afternoon would remind him again of improbability and mortality—and, though bringing gifts, would accidently fill him with remorse for having lost all sense of self and joined the ant-walkers that day.

Mr. Sasaki lived across the street from Hachiya, near the Misasa Bridge. He came to the hospital bearing freshwater ayu fish for the patients and staff.

“How is your family?” Hachiya asked.

Mr. Sasaki explained that it had taken him several days to find them because when the pika flared out, he was running an errand north of the hospital, and was forced to out-race the firestorm into the hills of Ushita. Only shadow-shielding from the heat ray, and the added speed given him by an intact bicycle, had allowed him to escape without injury. Yet even from a safe distance, upriver and in the hill country, he could see that his neighborhood was “under the mushroom’s stem.” After the fires diminished, Sasaki navigated his bicycle through debris-strewn streets and found his home, and Dr. Hachiya’s, reduced to knee-deep piles of ash. Fortunately, Shigeo Sasaki’s family had traveled upriver with other survivors from the neighborhood, to a pre-arranged meeting place at which it was hoped they would all re-connect if anything terrible were to disperse them. As Sasaki traveled downriver toward the ruins, his wife and children had passed him in the opposite direction, evacuating toward the upriver, suburban hospital to which he had been assigned. He finally reunited with his wife and children, discovering them mud-soaked and looking hungry, about the same time the tremors from Nagasaki reached out toward Hiroshima.

“Little Sadako keeps talking about the bright light,” Mr. Sasaki said. The child was only two, but not yet nor ever would she forget the false sunrise that preceded the great wind. Sadako’s five-year-old brother Masahiro and Mrs. Sasaki were bruised and shaken but safe. They had survived the picket of fire worms that advanced into the river and became waterspouts.33 They had even survived the rain of oil without suffering any symptoms of what Dr. Hachiya was now coming to call “atomic bomb disease.”34

“Were they inside the house during the pika-don, or outside?” Dr. Hachiya asked.

“Inside,” Mr. Sasaki replied, and Hachiya sighed with relief. “That’s how they got bruised,” Sasaki continued. “They were bounced around inside, and when they fled into the street, though the house seemed intact, it just sort of leaned slowly over to one side. And then, as the flames and the confusion grew worse, they eventually got separated from my mother and she was lost.”

“What?”

“They never did see her again.”

For all the horrors Hachiya had seen and experienced during the past week, the death of Mr. Sasaki’s kindly mother felt like one punch too many in the stomach. From what Hachiya was able to learn, little Sadako’s grandmother was burned to death as the firestorm developed, and like others caught in the maelstrom, once the fires seized control of the city, there was nothing that anyone could do to save her. But Hachiya had been right there before the fires dominated the landscape—and he remembered, vaguely, seeing the Sasaki house leaning to one side before it began to fall apart, just as Mr. Sasaki had described it.

From the moment of hearing that his friend’s mother had been injured and killed only steps away from him, it did not matter to Hachiya that he had emerged from the ruins of his own house, bleeding and confused, into a world turned suddenly and violently unfamiliar. All that mattered was that instead of helping his neighbor he had joined the nearest ant trail.

Not that Mr. Sasaki, who was every bit as kindly as his mother, would ever say a word of reproach against him. Instead, he would continue to bring whatever food he could spare for his neighbor, and for those under his care. Yet from that moment, the first sting of survivor’s guilt began to work its poison in Hachiya’s heart, and he would never be able to meet Sadako or her father without being brought back to the picture of himself as the sort of person who walked away in a time of dire need. His only hope of avoiding the pain was to avoid them. It was the beginning of what Dr. Nagai of Urakami was already coming to recognize as one of those invisible cracks made by the atomic bomb—a crack between neighbors and friends, although Hachiya and Sasaki would never talk about it.

“I have one more thing for you,” Mr. Sasaki said. “News from the prefect’s office. This is not rumor. It comes directly through Foreign Minister Togo. An important radio broadcast is announced for tomorrow.”

“What can it be?”

Neither man wanted to speculate, but both supposed that War Minister Anami was about to announce the advance of enemy fleets toward the homeland’s shores. He would presumably order every man, woman, and child to fight against the Americans to Japan’s own extinction—using cleavers, knives, and sharpened bamboo sticks.

For a while, Hachiya could put thoughts of ant-walker’s guilt aside in favor of thankfulness for being without electricity. We have no radio, he told himself, and realized that living empty-handed in the Stone Age actually gave him a freedom of spirit and action he had not known since the war began.35

Tanemori, the boy half-blinded by the bomb during a game of hide-and-seek, greeted the morning of August 15 as the day of Obon, the beginning of the period during which the spirits of the ancestors returned to visit places they had wished to see during life, or decided simply to stay near, watching over their descendants and loved ones.

As the reality of his father’s suffering began to send chills down his spine, Tanemori learned from the same unwelcoming relatives who had by now arrived at a decision to send father, and son, and a dying daughter outside to sleep on beds of hay in whatever shelter they could make for themselves, that on this day they would be welcomed briefly indoors. The occasion was an important announcement, scheduled to be broadcast on the radio, from the Imperial Palace.

Young Tanemori did not care what the announcement might be. With a trembling hand, Daddy held out to him a memento from his last visit to the ruined city: a fragment of bone from the chest of a child.

“This, I think,” Daddy said softly, “is—”

“No! No! No, Daddy! Tell me this is not Sayoko! Tell me!”

But only the dogs replied, with a frightful howling that came from many directions at once. The howls echoed, near and far; and Tanemori felt sick.36

In the Hiroshima suburb near Isao Kita’s weather station, Keiji Nakazawa awoke in a shed where he and his mother were no more welcomed by relatives than were the Tanemoris in Kotachi Village. Nakazawa felt strong enough this day to begin scouting for a better place to live, in addition to his usual search for food. On a patch of land near Paul Tibbets’s original aiming point, the “T” Bridge, a handful of survivors were already expanding lean-to shelters into the first corrugated zinc houses, in what was to become the Hiroshima prairie’s first shantytown. Nakazawa would eventually choose for himself a piece of ground barely more than a hundred paces northwest of the Rationing Hall in which Eizo Nomura had been shock-cocooned. The frame of the shock-cocooned building would one day be remodeled into a tourist center; and the shelter that Keiji Nakazawa planned to build for his mother was to occupy the same little parcel of land on which, decades later, would rise a tall pedestal, atop which a girl, sculpted in bronze, could be seen holding a paper crane up to the sky.

Along the spit of land where Nakazawa conducted his scouting operation for a new home, word spread that a radio was being set up for public broadcast near the weather station. A second public radio had been delivered by truck from the Communications Bureau to Dr. Hachiya’s hospital. Something important was about to happen to Japan, but Nakazawa could not have cared less what happened to the country or its leaders. What he did care about was sheltering and feeding his mother and saving his baby sister.37

At the appointed hour, someone on the hospital steps hooked an all but completely dead car battery to the radio, and the prairie was suddenly humming and crackling with fading static. A distant voice said, “We have resolved to pave the way for a grand peace for all generations to come, by enduring the unendurable and suffering the insufferable.”

Only a few people were able to hear this. All that came through clearly, before the battery failed, were the words “enduring the unendurable.”

The hospital’s electrician, who had been standing with his ear close to the speaker, announced that what everyone had just heard was the Emperor’s own voice, and that he had just said the war was over.

“Who won?” someone asked.

“He said we must bear the unbearable,” the electrician replied; and then, looking around, he added, “Who do you think won?”38

Keiji Nakazawa’s baby sister, whom he had named Tomoko because the word meant “friend,” was clearly dying.

Presently, some of the isotopes absorbed in his mother’s bones were being stealthily removed and rerouted to her milk glands, but they had already done their work and stem cells in her bone marrow, ravaged by chromosomal dislocations, were beginning to divide wrongly in a march toward eventual chaos and death.

Nakazawa’s father was dead.

Nakazawa’s older sister was dead.

Nakazawa’s little brother Susumu was dead.

By the night of the surrender, one of Keiji Nakazawa’s neighbors had joined the feral atomic orphans. Tanaka was the child of a high-ranking officer who used to live in a mansion across the street from the Nakazawa home. During the worst of the rationing leading up to August 6, when even potato vines were in short supply for meals, the army delivered canned meats and even sweets to Tanaka’s family.

Tanaka was the same age as Keiji Nakazawa and had befriended him; and although Tanaka occasionally shared food as well as toys, Nakazawa could not avoid a certain amount of jealousy and even anger. “They lived a truly luxurious life,” Nakazawa would write later, “and the difference between them and us was heaven and hell.”

Keiji (“Barefoot Gen”) Nakazawa barely escaped becoming an atomic orphan, and lived to tell what he saw through his Manga art. [Illustration: CRP]

In his chronicles of Barefoot Gen, Nakazawa did not mention how his older brother Koji began wandering away, where he found new friends and became increasingly involved in the trafficking and consumption of alcohol. Koji’s activities in the emerging black markets brought home rations of rice; but they also created a rift within the family. What the chronicler of Gen did write about was the night Tanaka, drawn by the scent of food, snuck under one of the sheet-metal slats on the side of the makeshift shack Nakazawa was building for his mother and sister. The former neighbor from across the street tried to flee with a jar of rice.

In his chronicles, Nakazawa disguised Tanaka and called him “Ryuta.” During the sixty-fifth anniversary of the atomic bombings, following a controversy in which Ryuta would be wrongly declared to be a fictional character, invented to manipulate the emotions of readers, Nakazawa decided to reveal the details of a subject that had been very painful for him, and about which he routinely avoided speaking directly. In the world of Barefoot Gen, the strained, on-again off-again friendship between Gen and Ryuta simply faded mysteriously, leaving behind a lasting impression that leukemia or some other manifestation of atomic bomb disease must have intervened. But “Ryuta’s” actual fate seemed to Nakazawa to be somewhat worse than the after-effects of radiation exposure because it might have been preventable.

“His name was Tanaka,” Keiji Nakazawa would finally cry out to history, wanting the generations to remember. “He was Ryuta.”

In Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen chronicles, the truth about Tanaka was located somewhere between what he wished would have happened (Ryuta as a new brother, replacing two siblings lost) and what really happened.

As Keiji Nakazawa would grow up to tell it, in his Manga and in a film, a gentle, shadowy movement under the slat where rice was stored called him to action one night, and moments later he was wrestling on broken concrete outside the shack. Finally, Nakazawa wrapped his legs around the boy’s waist; and as his mother emerged from the shack commanding him to stop and as the light from her lantern struck the boy’s face, Keiji Nakazawa drew back his fist to strike the thief, then drew his breath in astonishment.

The boy looked like Tanaka, yet at the same time he no longer looked at all like Tanaka. On some level of Nakazawa’s thinking, the boy looked just like the little brother he was still mourning. Whether the resemblance arose from a change in Tanaka’s features, brought about by near-starvation, or whether hopeful thinking made any young waif transform into a twin of Susumu, would never be clear.

“Susumu?” Nakazawa asked, as recalled for his late-20th-century screenplay of Barefoot Gen.

“I’m not him,” the boy said, squirming away and getting ready to jump to his feet again.

“Of course you’re not Susumu,” Kimiyo Nakazawa said, as calmly and gently as she could. I saw him die, she left un-emphasized, for Keiji’s benefit.

“I’m sorry I stole your food,” Tanaka said, letting his friend’s mother help him to his feet. He tried to explain the hunger that had been gnawing at him until at last he believed he had lost his appetite. And then he smelled cooked rice, and he could not control himself. “But God says it’s not a sin to steal food if you’re really, really hungry.”

“Tanaka, where is your family?” Kimiyo asked.

Clenching his jaw, he answered, “They were all killed in the explosion.” Tanaka alone crawled out from beneath the wreckage of the mansion. In his yard, family members had been hoisted into the air just like Keiji Nakazawa’s mother, except that in this case they landed in trees and were hung from seared branches, impaled. People no longer identifiable to Tanaka as either strangers or relatives crawled silently away from the flattened home. Their abdominal muscles were sliced open and they had seemed unaware that their knees were snagging on their own dangling internal organs, drawing out ropes of intestine, yard by yard, as they crawled.

Keiji Nakazawa listened to Tanaka’s story impassively, as if all horrors could now be ignored as background noise—which, in fact, they could. He was preoccupied with other thoughts.

“You look exactly like my little brother,” Keiji said again, as told through his alter ego, Gen.

“I’m not him!” the boy yelled, taking a resentful step backward. “I’m Tanaka!”

“Barefoot Gen” said nothing. He simply looked at “Ryuta” apologetically, then ran into the shack and returned with a half-eaten rice ball. “Here,” he said. “You can have the rest of my dinner, if you want it.”

“You mean, you’d give it to me?”

“Sure.”

And before he could quite hand it over, the orphan had taken a huge gulp out of the rice ball. He then tried to swallow the rest of it in a second gulp that almost choked him.

“What are you doing?” Keiji asked. “You’ll get sick.”

The orphan swallowed hard and said, “I didn’t want you to take it back.”

“I wouldn’t do that,” Keiji Nakazawa assured.

“Why should I believe you?”

Kimiyo Nakazawa knelt down, until her head was level with the orphan’s. “Where have you been living since the explosion, Tanaka?”

“Out here, mostly.”

“Well, if you’re still hungry, you’re welcome to finish my rice, too.”

“You really mean that?”

“Of course I do.”

Kimiyo watched the boy gulp down the second rice ball as fast as the first. It shocked and amazed her. Little Susumu had also been in the habit of gulping his food, as if he actually feared that someone might snatch it away from him before he had a chance to swallow.

As told through the wishful perspective of Gen, Keiji Nakazawa brought out a dented copper cooking pot and offered to “Ryuta” a spoon to scrape out any last remnants of crisped rice. He dropped the spoon, put his head right inside the pot, and began licking and gnawing the sides. “Just like Susumu used to do,” Keiji whispered.

Kimiyo tried to explain to her son, and perhaps to herself, that for a child of the wilderness—a former neighbor—to have taken on Susumu’s mannerisms, and for the child to have found them by accident seemed remarkable. “Somehow,” she said, “it’s as if he were sent here.”

Keiji Nakazawa watched the orphan he wished to be his little brother licking all the way to the bottom of the upturned pot, seeking out every last trace of flavor. “Mother,” Keiji said, “are you thinking what I’m thinking?”

“I am. But we’re having such a difficult time feeding ourselves—” and she watched the copper pot become a large helmet over Tanaka’s head. “But still, if Susumu were alive, it’s what he would want us to do.”

“So, it’s all right, then?”

The orphan did not hear the question. His entire head and now one of his shoulders had disappeared into the pot. When at last he rolled it onto the ground and announced that he almost didn’t feel hungry anymore—“almost”—he noticed that the kid from across the street and his mother were staring at him with very strange expressions on their faces. At first, he interpreted the expressions as meaning he had offended them somehow and was about to be wrestled to the ground again. Then he remembered his manners.

“Thank you!” Tanaka said quickly. “I’m so sorry. I should have said thank you.”

He received the same stare, from both of them.

“What did I do?”

“Nothing,” Kimiyo said. “Tanaka, we’ve been wondering. Would you like to have a home again?”

“You mean, stay here?” he asked hopefully.

“Yeah,” Keiji Nakazawa said.

The boy looked scared, as if in the next moment Keiji and his mother might say, “Only kidding,” and send him away again into the wilderness. As Nakazawa’s Gen chronicles would record it, the orphan began talking about his shortcomings and tried to explain why these were really not so bad: “I know I’m little and can’t work very hard and be much help, but I can give you back rubs. Father always said I was a good back-rubber.” And he went straight to Kimiyo Nakazawa’s shoulders, pinching all the right nerves in all the wrong places.

“That’s very kind of you,” Kimiyo said, “but you don’t have to work hard. We’re not asking anything from you in return, Tanaka. You’ll just be one of the family.”

“Really?”

Kimiyo nodded, and gently stroked his head. A tiny clump of hair came out in her fingers. It did not matter. Tanaka, who had not believed he would ever feel happy about anything again, was crying with joy.39

Each time Takashi Tanemori’s father returned from Hiroshima to their shed, his eyes and his cheeks had receded deeper into his skull. Until he unearthed a child’s bone, near what he believed to be the foundation of the family home, Daddy had held out some small hope that the rest of his family were only missing, and were still alive out there, somewhere.

“Now I know where your mother is,” Daddy announced. “She is not in Hiroshima. And I know that I shall see her soon.” He handed his son a pair of scissors and asked, “Can you cut my hair, and make me look handsome for her?”

Takashi Tanemori held the scissors in his left hand, and began combing Daddy’s hair with the fingers of his right hand, preparing to make the first cut. With barely the slightest resistance, the hair uprooted and combed out into his fingers, in great clumps.

The boy cried, “Daddy, I’m sorry. I’m so sorry!” He tried to push the hair back onto his father’s head, pressing and patting with both hands.

“Son, it’s all right,” Daddy said. “Your father is very tired now. I need to rest for a few minutes.” Takashi helped him to lie down, placed a soft pillow under his head, and stayed very close, listening to his breath catching on every intake, often between long pauses. Time itself seemed to have become elastic to the boy, with days becoming indistinguishable from hours. Daddy was speaking deliriously to someone who was not there in the lamplight, “as if some spirit had arrived with its secret only for him.”