On October 23, 2002 the hostage-taking in Moscow by Chechen terrorists of the audience of a musical, Nord-Ost, made worldwide headlines. Anna, who attempted to negotiate inside the theatre with the terrorists, was ultimately able to show with a high degree of certainty, with information provided by the FSB whistle-blower Alexander Litvinenko, since murdered, that this event and its disastrous outcome had been another production of the Russian regime.

October 24, 2002*

From the Editors of Novaya gazeta:

12:30 p.m.

Novaya gazeta’s columnist Anna Politkovskaya is prepared to enter negotiations with those who have seized hostages in Moscow. She is sympathetic to their demands for an end to the Chechen War, but disapproves of their methods. Civilians should not suffer because of mistakes made by the state authorities.

Anna Politkovskaya is currently in Washington, DC where she was engaged in discussions with senior State Department and White House officials about finding a peaceful solution to the Chechen issue. Others taking part in these discussions included Ilias Akhmadov, a politician respected by the Chechens; Dr Zbigniew Brzezinski, former US Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs; and Lord Judd, who has several times visited Chechnya on behalf of the Council of Europe. Thus Anna Politkovskaya, although far from Russia, was effectively engaged in fulfilling the demands of the hostage-takers in Moscow.

As soon as she returns to Moscow, which can be no sooner than 13 hours from now since the first plane to Moscow leaves Washington in four and a half hours’ time, she will immediately go to the scene of the events and contact the hostage-takers. Unfortunately, representatives of the US Embassy are asking us to wait until 9:00 a.m. local time (it is currently 5:00 a.m. in Washington, DC) to seek official assistance. It seems to us that we are asking for a very small favor of getting someone on the first flight from Washington to Moscow. Lives – including those of American citizens among the hostages – depend on this favor. Anna Politkovskaya is the only person in whom the hostage-takers have expressed confidence and whom they have requested as a mediator in the negotiations.

We urge the Americans to help Anna Politkovskaya return to Moscow as soon as possible.

1:30 p.m.

As of now the issue of facilitating an emergency flight from Washington, DC to Moscow for Novaya gazeta’s columnist, Anna Politkovskaya, remains unresolved. The hostage-takers in Moscow have expressed a wish to negotiate with her.

As Anna is presently in America, we appealed to the US Embassy for help and received a reply from Mr Paul Carter of the Embassy’s Legal Department. He said they were prepared to assist, but required confirmation from the Russian Foreign Ministry that this was a government initiative, and that the state was prepared to negotiate rather than to resolve the problem by force.

We rang the North American Department of the Russian Foreign Ministry, who confirmed that Paul Carter had phoned them but said that, “since this matter was not within their jurisdiction,” they could not take any decision and would not involve themselves in facilitating Anna Politkovskaya’s urgent return to Russia. They advised us to phone the operational information section of the Foreign Ministry, whose Director, Vladimir Oshurkov, said he had “no information for the mass media.” We asked whether they would in fact ask the Americans to help, to which Mr Oshurkov replied, “What has the Ministry of Foreign Affairs got to do with this anyway? Why should the Ministry bother itself with getting Anna Politkovskaya to Russia? That’s what the security ministries have staff for. If they consider it necessary for Anna Politkovskaya to return to negotiate with the terrorists, she will fly. It is nothing to do with the Foreign Ministry.”

In order to re-register her ticket, Anna Politkovskaya requires more than 1,000 US dollars. If our Foreign Ministry (which represents the Russian Government) does not wish to address the problem, jeopardising negotiations with the hostage-takers and thereby putting at risk the lives of the hostages, we shall find the money ourselves.

2:30 p.m.

The latest information is that Anna Politkovskaya is returning to Russia on the first available flight.

October 28, 2002

My personal involvement in this crisis began at about 2:00 p.m. on October 25. At 11:30 a.m. I had spoken on my mobile phone to the hostage-takers for the first time and they agreed to a meeting. At 1:30 p.m. I arrived at the headquarters of the security operation. Another half-hour was spent getting everything co-ordinated: some unknown person was resolving matters behind doors which kept slamming.

Finally, I was led up to a protective cordon of trucks, someone said, “Give it a go. Perhaps you can do it,” and Dr Leonid Roshal [Head of the Disaster Medical Center] and I made our way to the entrance. It was very frightening.

We went into the building. We shouted, “Hello! Anybody there?”

There was no response. It felt as if the building was completely deserted.

I shouted, “It’s me, Politkovskaya! It’s Politkovskaya!” I slowly started climbing up the right-hand staircase. The doctor said he knew the way. In the first-floor foyer there was again silence, darkness, and it was cold. Not a soul. I shouted again, “It’s Politkovskaya!” Finally, a man appeared from behind what had been the counter of the bar.

His black mask wasn’t on properly and I could see his features clearly. He was not aggressive towards me, but hostile towards the doctor. Why? I don’t know, but I did my best to calm a situation which was becoming heated. “What are you up to, doctor, helping your career along?” the man in the mask taunted. Dr Roshal is 70 years old, an Academic, and has already achieved so much that he really doesn’t need to worry about his career.

I said as much, a bit of an argument started, and it was time to lower the temperature again since otherwise … Otherwise it was obvious what could happen.

The man with the ill-fitting mask went off into the depths of the darkened foyer, still muttering, “Why do you say you treat Chechen children too, doctor?” There was some further fairly incoherent nastiness which amounted to suggesting that mentioning that he also treated Chechen children showed he didn’t think they were the equal of other children, perhaps even that Chechens are not human beings.

It was a familiar tune and I interrupted it, not because that was a particularly clever thing to do but simply because I had had enough. I said, “All people are the same. They have the same skin, the same bones, the same blood.” This less than original thought unexpectedly had a conciliatory effect. I asked permission to sit on the only chair in the middle of the foyer, 5 metres or so from the bar, because my legs had turned to jelly.

Permission was immediately granted. My shoes slipped on some disgusting red mess trampled into the carpet. I looked down cautiously at this ghastliness, anxious not to seem to be taking too much of an interest, but even more anxious not to put my feet in congealed blood. Thank God, it was only some kind of dead dessert, possibly fruit and ice-cream. I trembled a little less.

We waited 20 minutes or so while the leader was sent for. While we waited there, heads in masks appeared over the balcony occasionally. Some of the masks covered their faces properly, others only did half the job.

“Was it you who helped the people in Khotuni against the paratroop regiment?” the heads ask.

“Yes.”

The heads are satisfied. Khotuni, a village in the Vedeno District, turns out to be my safe-conduct pass. If I have been there I am worth talking to.

“Where are you from?” I ask the man from the bar counter.

“Tovzeni,” he replies. “Many of us are from Tovzeni, and from Vedeno District generally.”

There follows a lot of confused coming and going by men in masks, the sign of a tragedy in the making. Time just passing by, disappearing into nowhere, fills me with idiotic foreboding. The leader still hasn’t appeared. Perhaps they are going to shoot us here and now.

Finally, a person in combat fatigues comes out, his face completely covered. He is stocky, and with exactly the deportment of Russian special operations officers who give serious attention to their physical fitness. He says, “Follow me.” My legs again turn to jelly, but I wobble after him. This is The Leader.

We end up in a dirty service room by a ransacked buffet, behind which is a water tap. Somebody walks behind me and I turn. I realize this looks nervous, but what can I do? I haven’t had much experience of talking to terrorists under conditions as tense as these. The leader brings me back to cold logic.

“Don’t look behind you! You are talking to me, so look at me.”

“Who are you? What should I call you?” I ask, not really expecting a reply.

“Bakar. Abubakar.”

By now he has pushed the mask up to his forehead. He has an open face with high cheekbones, also very typical of our military. He has a rifle on his knees which he puts behind him only at the very end of our talk, when he even apologizes. “I’ve got so used to it I no longer feel it there. I sleep with it, eat with it. It is always with me.” Even without this explanation I already understand everything.

“How old are you?”

“Twenty-nine.”

“Have you been fighting in both wars?”

“Yes.”

“Did you sit it out in Georgia?”

“No. I never left Chechnya.”

Bakar belongs to a new generation of Chechens who for the past 10 years have known nothing but a rifle and the forests. He left school, and life in the forests became his only option. A destiny devoid of choice.

“Shall we get down to business?” I suggest.

“OK.”

“First, the older children still in there. You need to let them go. They are only children.” Sergey Yastrzhembsky, Aide to the President of the Russian Federation, had asked me to raise this with them as my main priority.

“Children? There are no children in there. In security sweeps you take ours from 12 years old. We will hold on to yours.”

“In retaliation?”

“So that you know how it feels.”

I return to the subject of the children many times, asking for them to be allowed at least some relief, for me to bring food, for instance, but the answer is a categorical no.

“Do you let ours eat in the security sweeps? Yours can do without too.”

I have four other requests on my list: food for the hostages, items of personal hygiene for the women, water, blankets. To anticipate, I get agreement only to bring water and juice. I will be allowed to bring them, shout from downstairs, and then I will be let in.

“Can I come several times? I can’t carry much in one go. There are so many hostages. Perhaps you will allow me to bring one of the men.”

“OK.”

“Do you mind if that’s another of our journalists?”

“No. And also somebody from the Red Cross.”

“Thank you.”

I start asking what it is that they want, but politically Bakar is all at sea. He’s a simple soldier and no more. He explains what this is all about, at considerable length but not at all clearly, and from what he says I identify four points. The first is that Putin must “give the word” – declare an end to the war. The second is that within 24 hours he must demonstrate that these are not empty words, for example by withdrawing troops from one of the districts.

“From which district? From yours? Vedeno?”

“What are you, a GRU agent? You’re interrogating me like a GRU agent. That’s all I’ve got to say, go away!”

It is impossible for me to go away at this point, although I very much want to. I hear myself almost pleading, which is completely the wrong tone, of course:

“Please understand, I need to know what it is you want. And I need to know exactly. Otherwise …”

From time to time I trip over myself. I am racking my brains over an intractable problem: how can I ease the plight of the hostages as much as possible, since the hostage-takers have at least agreed to talk to me, but not lose my credibility in their eyes? And I am making a mess of it. Quite often I can’t think what to say next, and blurt out a lot of nonsense, just hoping not to hear Bakar say “That’s it!,” whereupon I would have to leave empty-handed, having failed to negotiate anything at all for the hostages. As we approach the third point of “their” plan, Boris Nemtsov [chairman of the Union of Right Forces political coalition] phones Bakar on his mobile. The resistance fighters took it from one of the hostages, a Nord-Ost musician, and now they are using it for all their conversations.

While he is talking to Nemtsov, Bakar becomes very agitated. Afterwards he tells me Nemtsov is trying to trick him. Nemtsov said yesterday that the war in Chechnya could be ended, but today, October 25, the security sweeps have been renewed. Then I ask, “Who will you believe? Who would you trust if they told you that troops were being withdrawn?”

Only Lord Judd, it transpires, the Council of Europe’s rapporteur on Chechnya.

We get to “their” third point, which is simple: if the first two demands are met, they will release the hostages.

“And yourselves?”

“We will stay behind to fight. We will behave like soldiers and die in battle.”

“But who in fact are you?” I ask, scaring myself with my audacity.

“The Reconnaissance and Sabotage Battalion.”

“Are you all here?”

“No. Only some of us. We had a selection process for this operation and chose the best. If we die, there will still be others to continue our struggle.”

“Do you accept Maskhadov’s authority?”

He is thrown by this, and again becomes extremely irritated. His rambling explanation is best summarised as, “Yes, Maskhadov is our President, but we are fighting on our own.”

This is confirmation of my worst fears: the group is one of those acting independently in Chechnya. They are waging their own very radical war autonomously. By and large they have no time for Maskhadov, considering him insufficiently hard-line. I continue:

“But you do know that peace negotiations are being conducted by Ilias Akhmadov in America, and Akhmed Zakayev in Europe, who both represent Maskhadov. Perhaps you would like to contact them now? Or let me dial them. Yours is the same cause.”

“What for? We don’t acknowledge them. While we are dying in the forests they are slowly conducting their negotiations because it is not their heads the rain is falling on. We are fed up with them.”

There is no real fourth point to their plan, other than some strongly felt remarks of Bakar’s own: “People have been asking to come here as suicide bombers for a year and a half,” and “We have come to die.” I have no doubt of that. These are doomed men and women prepared to die, and to take with them as many lives as they see fit.

The mobile phone rings again. Bakar listens. It is a phone call from home, from the Vedeno District of Chechnya. He starts shouting and raging: “Don’t ring here any more. Ever. This is the office. You are interfering with my business.”

“May I talk to the hostages?”

“No.”

But five minutes later, he says to a “brother,” sitting almost behind my back, “OK, bring one.”

He goes and brings from the auditorium a terrified, pretty girl called Masha. The hostages have had nothing to eat and she is so frightened and weak that she can’t speak.

Bakar is irritated by her mumbling and orders her to be taken away. “Bring another one, older.” In the interim, Bakar tells me how noble they all are. They have so many pretty girls in their power – and Masha really is very pretty – but they have no desire. All their strength is being kept for the struggle for the liberation of their land. I understand him to mean that I should be grateful for their not having raped Masha.

We speak briefly about morality and ethics, if these are the right words.

“You won’t believe it, but morally we feel better here than at any time in the past three years of the war. We are finally doing something. We feel entirely at home. We feel better than ever. We will be glad to die. The fact that we will go down in history is a great honor. Don’t you believe me? I can see you don’t believe me.”

Actually, I very much do believe him. This kind of talk has been heard among Chechen fighters for a year already. Resentful of the virtual Maskhadov’s inaction, many resistance units have sat through an entire winter in the forests and have now had enough. They can’t come out of the forests, they can’t fight. They need something to do, but there are no orders from their Commander-in-Chief. As this mood has grown, units have either fallen apart or become radicalized, in effect embarking on parallel wars over which Maskhadov has no authority.

The “brother” brings another pretty girl in a state of extreme nervous exhaustion.

“I am Anna Andriyanovna, a correspondent of Moskovskaya Pravda. Everyone outside must please understand, we are already expecting to die. We realize that Russia has abandoned us. We are a second Kursk [a submarine which sank with the loss of all hands shortly after Putin became President]. If you want to save us, come out to demonstrate in the streets. If half of Moscow begs Putin, we will survive. We can see clearly that if we die here today, a new slaughter will start in Chechnya which will rebound on Russia and cause new carnage.”

Anya talks incessantly. Bakar is getting edgy but she doesn’t notice. I am again very much afraid that he will decide to be masterful. Finally she is taken away and we agree that I shall organise things at once and bring some water into the building. Bakar unexpectedly adds, “And you can bring some juice.”

“For you?”

“No, we are preparing to die; we are not eating or drinking anything. For them.”

“And perhaps some food? If only for the children.”

“No. Ours are starving, so let yours starve too.”

I go outside. I find that Dr Roshal has already left. It begins to pour, damn it, just at the wrong moment. “I haven’t even got an umbrella,” I think. “I look like a wet hen.” Well, you have to think something.

We have a whip round among everybody standing nearby. The journalists are the first to dig deep, and the firemen. Somebody runs to the nearest shop to get juice. We find that the representatives of the state have no change available at this moment. That seems odd, but there is no time to think about it, only the realisation that we must move as quickly as possible before the hostage-takers change their minds.

The juice is brought back. Roman Shleinov (a colleague at Novaya gazeta) and I take two packs each in our arms and try to walk. On our right is an Interior Ministry officer, on our left an FSB officer. They are arguing. The one from the Interior Ministry has orders to allow us in since this is aid for the hostages and represents an opportunity to prolong contact with the outlaws as long as possible. The one from the FSB has orders not to let us through.

They quarrel. The rain pours down and we stand there like idiots in full view of all the snipers, just waiting, it seems to me, for someone to start shooting. Finally the FSB agent agrees: “Go on, then.”

We take one batch and then another. Darkness falls; the gunmen had told us to bring it before dark but a criminal amount of time passes before the state manages to come up with juice for the next batch.

The third time, they allow a group of male hostages out to meet us. I’m afraid to say anything to them in case the hostage-takers start shooting. I just say “Hello,” and they reply. They are allowed out in single file. A young man in evening dress and a white shirt passes me. Presumably he plays in the orchestra. He whispers tersely, “They have told us they will start killing us at ten this evening. Pass it on.”

The next time I just nod silently to him, making eye contact, to let him know I have told the relevant authorities. They are leading the hostages down the steps to meet us, perhaps intending to make a point of showing how well they are treating them. Picking up his crate of juice, my musician whispers on the way back, “Understood.”

The gunmen suddenly start becoming very nervous. They shout and pace up and down. A hostage calls from above, “Bring some disinfectant. We really need it. We did ask for it.” He is driven back. I ask permission to bring the disinfectant, but am met with a complete refusal.

“At least some food? Just a little? For the children? Please …”

“We are dying of hunger, let them die of hunger too. Go away.”

This day in history comes to an end, to be followed by the assault. Now I keep asking myself whether we did everything possible to help avoid those deaths. Was it a great victory to have 67 hostages killed (excluding those who died after they got to hospital)? Was I any help to anyone with my juice and my last-ditch efforts? I believe I was, but that we could have done more.

Too much is now behind us, and a great deal still lies ahead. The tragedy of Nord-Ost, for which there were of course reasons, will not be the end. From now on we will have to live in constant fear when our children or old people go out of the house. Will we ever see them again? It will be just the way people in Chechnya have been living these last years.

There are only two alternatives. The first is finally to recognise that the more excessive force we use there – the more blood, killings, abductions and humiliations – the more people there will be in Chechnya who want revenge at any price; the more recruits there will be to the ranks of those wishing to die in retaliation.

And since this war will be fought not on a battlefield but amongst us, involving completely innocent people – you and me, and all of us – we can be sure that there will be another Nord-Ost, and that nobody anywhere can feel safe, whether going out or staying in their own flat. A cornered fighter will devise ever more ingenious means of retribution.

The second option is fraught with difficulties, but is at least a move in the right direction. We need to start talking to Maskhadov, a man clinging to what little remains of his power. Otherwise we are doomed to conduct negotiations like those over Nord-Ost within a framework of hopelessness, with innocent lives at stake.

November 4, 2002

The last few days have passed in a feverish delirium. Moscow is burying the hostages. Today, just like yesterday, just like tomorrow. It is unbearable. The faces of the dead are calm, not contorted, as if they had simply fallen asleep. And actually that is just what they did, because Russia failed to administer the gas [used prior to the assault] in the correct concentration.

I make it a rule not to write reports from funerals but this will be an exception. Lena, my old, dear friend, is burying her son Andryusha and her husband Sergey. On October 23 the three of them went to the theatre together. They were seated together, waited together for help to come, but only Lena survived.

The coffins of Andryusha and Sergey are side by side in the church, with a narrow passage between them. There are so many people you couldn’t push your way through. Nobody makes any speeches, there is no politics, only Lena walking up and down this passage, murmuring from time to time. When she stops walking she rests a hand on each coffin and tries not to collapse. She lowers her head between the coffins and so resembles a bird with outspread wings, or somebody wounded struggling to get to their feet.

I too am terribly, irredeemably guilty for what has befallen Lena, and only I know why. It is too late to do anything about it.

After the funerals I fly to Paris for a few hours and very soon regret having done so. The television station France 2 has invited me to take part in the country’s most popular Saturday evening program. I agreed only because people were telling me how little the West understood what is happening in “the East.”

On the show, compered by French television celebrity Thiérry Ardisson, a well-known French singer was to perform immediately before me. I didn’t write his name down and can’t remember it now. There was also the Minister of Health from the Chechen Government when Maskhadov was in power, Umar somebody. Torrents of words poured forth about the Chechens, and how long and tirelessly they have been fighting for their freedom. The singer thought it was terrific, as did the presenter. It only left a very short time for me to say … Well, to say what, now that I had this prime-time opportunity?

I spoke badly, briefly, and not at all to the point. It was a disgrace, of course, because if you are given an opportunity to state your viewpoint, you should be ready to do so. No matter how hard I tried, though, I felt completely alien in this environment. We were on different wavelengths. Nobody in the audience wanted to hear about what, having just come from all these funerals, mattered most to me – the victims, the dreadful consequences. The Ichkerian Minister of Health (who really had nothing to do with anything, and who seemed rather at sea) found himself the focus of a whirl of emotional exclamations from admiring, ecstatic Frenchwomen of the same, far from young, age as me. Their superficial, romantic nonsense left me feeling nauseated, because they were as blind to the reality as … well, as we are. Only for them, Chechens are all good, and for Russians they are all bad.

I flew back to Moscow. The World Chechen Congress took place in Copenhagen immediately after the assault, and was subjected to an unprecedented barrage of protest from the Kremlin, which cancelled visits and summit meetings. (Moscow had to make do with the arrest of Akhmed Zakayev as a booby prize from the Danish Government.) On November 1 the Moscow participants of the Congress, in accordance with its concluding resolution, laid a wreath where the Nord-Ost victims had died.

They invited me to join them, but I didn’t. The first reason was simply that, on principle, I avoid marching in columns and have never laid anything anywhere as a member of a crowd. The second reason was even simpler; I was still on the plane. There was, however, a third and most important reason, which I am sad about and unsure how to express, but which I think I need to explain.

Something wasn’t quite right about this wreath-laying ceremony. It wasn’t because, as so many people now believe, “the Chechens are to blame for everything.” Even less was it because I personally have anything against Chechens. Of course I haven’t.

But I really didn’t like the way most of the Chechens I know behaved during those 57 hours when everything was on a knife edge, when at any moment the Nord-Ost audience might have been blown sky high, when a message from influential Chechens addressed to those under Barayev Junior’s command would have carried far more weight than anything anybody else could say. That, at least, is how I felt. They said nothing. No statement came, and now their silence is a historical fact. That is the other reason I was so upset by those nauseating Frenchwomen.

Only Aslambek Aslakhanov, a Chechen and a Deputy of the Russian Duma, went in to talk to the terrorists, despite the fact that his act could have had extremely unpleasant consequences for him: he is, after all, an Interior Ministry general, and unambiguously a “federal” in the minds of those who took the Nord-Ost audience hostage. But Aslakhanov went in, despite his own young children at home. He went in, and that too is a matter of record.

But where were all the others? Where was businessman and politician Malik Saidulayev? Where were the Umars? (I’ve forgotten their surnames too, and really can’t be bothered trying to rediscover them.) I mean that rich Umar somebody who owns a hotel near Kievsky Station in Moscow. And what about Bislan Gantamirov, sometime Mayor of Grozny? And Salambek Khadzhiev? And so on and so forth, ad infinitum?

None of them spoke out; not even Kadyrov, whom most of the Moscow Chechens are so busy buzzing around when he comes from Grozny that you start having dark suspicions about vested interests on both sides. In his old age, Kadyrov has covered himself with ineradicable shame by valuing his own life higher than the lives of 50 completely innocent spectators of the Nord-Ost musical. The terrorists invited him, as the Chief of Chechnya appointed by Putin, to visit them in exchange for 50 hostages but he didn’t go, subsequently claiming he “hadn’t heard about it.”

During these 57 hours, the Moscow Chechens were whispering in corners. That was completely inadequate. They didn’t even decry Kadyrov, or attempt to persuade him to go down in history as a man who saved the lives of 50 women and children. For 57 hours the so-called Chechen diaspora, almost to a man, went underground, some of them turning up only in Copenhagen.

My own feeling is that this leaves a bad taste. It just wasn’t the way these people ought to have behaved. Perhaps I am completely wrong and I will be told later that the Chechens were terrified of the consequences, and that their main priority is to survive in a society now bristling against them even more than before, and so on and so forth.

No doubt that is all true, but can you really rank fears? The diaspora seemed heedless of the fact that the hostages were even more terrified of what seemed like their imminent inevitable death; and that for more than 100 of them (and we still don’t know how many more) those 57 hours facing death were the last hours of their lives. That is why today we are attending funeral after funeral where the priests lose their voices because even their highly trained vocal cords cannot cope with so many services.

So, should we sympathise with the fears of the Chechen diaspora? Absolutely not. You will have to excuse me, but I totally reject their fear. Everybody involved was scared, including those who mounted the assault and those on the receiving end of it. So let us come back to our initial question: why did the Chechens behave as they did during these 57 hours?

Because they are cowards. Faced with their own younger generation who have turned into uncompromising radicals the whole lot of them bottled out. They slunk away. And perhaps, too, they considered it all beneath them. They think they are so elevated, but now we can see how low they are.

That too is a fact of history. The myth of the incomparable fearlessness of the Chechen nation has been relegated to history, to the period before October 23, 2002.

In Chechnya security sweeps are proceeding incessantly. People are being tortured, suffering just as much as before. Villages have been blockaded. The zone behind the Chechnya barrier has once again been turned into a training ground for the Army. On this side of the barrier things are better, but not much.

April 28, 2003

Six months ago there was a terrorist act at the Nord-Ost musical. Since then we have puzzled many times over how such a thing could have happened. How did they get into Moscow? Did someone allow it? Why? Now we find there is a witness, who was also a member of the terrorist group.

At first there was only the bare information that one of the group of terrorists who took the audience hostage was still alive.

We checked the information out, repeatedly analysed the list of Barayev’s group published in the press, made enquiries, and tracked him down: a man whose name is indeed officially listed with those of the other terrorists.

Were you a member of the Barayev group who took the Nord-Ost audience hostage?

Yes, I was.

Did you go into the theatre with them?

Yes.

I read an ID document with “PRESS” on its cover in capital letters on a dark background: “Khanpash Nurdyevich Terkibayev. Rossiyskaya gazeta. Special Correspondent. Pass No. 1165.” Signed Gorbenko. Sure enough, Rossiyskaya gazeta does have a director of that name.

What topics do you write about? Chechnya?

No reply.

Do you go in to work at the newspaper? What department do you work in? Who is your editor?

Again, no reply. He pretends not to understand Russian very well, but how can you be a special correspondent of the country’s main government newspaper if you don’t speak Russian? Khanpash’s narrow, mongoloid eyes, not much like those of a Chechen, register incomprehension. He is not putting it on, he genuinely does not understand what I’m talking about. He is no Russian journalist.

Was this pass given to you by someone as cover?

He smiles slyly:

I would not mind writing. I just haven’t had time yet to think about it. I only received this pass on April 7. See the date? I don’t need to go into the office, I work in the President’s Information Service.

Under Porshnev? What job do you do?

(Igor Porshnev heads the Information Service of Putin’s Presidential Administration, which should make him Khanpash’s immediate superior.) Even Porshnev’s name produces incomprehension in Rossiyskaya Gazeta’s “special correspondent.” Khanpash has no idea who Porshnev is.

When necessary I meet [Presidential Aide] Yastrzhembsky. I work for him. Here is a photograph of me with him.

Sure enough, here is Khanpash photographed with Sergey Yastrzhembsky. Sergey is looking past the camera and appears displeased. Khanpash, on the other hand, now sitting in front of me in the Sputnik Hotel on Lenin Prospect in Moscow, is looking straight into the lens, as if to say, “There! That’s us.” You can tell from the photograph how palpably unwelcome it was to Yastrzhembsky, and deduce that it was insisted upon by the man now telling me his complicated life story, punctuating the narrative with numerous photographs which he pulls from his briefcase. “That’s me and Maskhadov, me and Yastreb, me and Maskhadov again, me and Arsanov, me in the Kremlin, me and Saidullayev, me and Gil-Robles (the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner).”

I look more closely, and quite a few seem to be rather inexpert photomontage. (They were subsequently checked by specialists and this was found to be the case.) “What’s the game?” I ask. Khanpash again looks uncomprehending, rummages in the briefcase and pulls out “me with Margaret Thatcher and Maskhadov,” to show how familiar he is with the London scene. It is 1998, Maskhadov is wearing a tall astrakhan hat, Thatcher is in the middle, and Khanpash is on the other side. Intriguingly, Maskhadov looks as he did before the war, while Khanpash looks as he does today. Odd. But he is already showing me another photograph of himself with Maskhadov during the present war. Maskhadov is wearing combat fatigues, his beard is very grey, and he looks terrible. Khanpash doesn’t look too chipper either. This one is genuine.

Aren’t you afraid of walking around Moscow with photographs like these? In Chechnya they would shoot you on the spot for the one with Maskhadov. Here they will plant firearms on you and put you in prison for years. He replies, “I am in with Surkov.” Khanpash begins to sound boastful. “After Nord-Ost I visited Surkov. Twice.” (Vladislav Surkov is the influential Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration of Russia.)

Why?

I was helping him to work out a Chechen policy for Putin. After Nord-Ost.

And were you able to help?

Peace is needed.

That’s an original thought.

I am currently working on peace negotiations for Yastrzhembsky and Surkov. The idea is to negotiate with the fighters hiding in the mountains.

Is that your idea or the Kremlin’s?

Mine, supported by the Kremlin.

Negotiations with Maskhadov?

No. The Kremlin will not agree to negotiate with him.

With whom, then?

With Vakha Arsanov [former Vice-President of Ichkeria, repudiated by Maskhadov]. I have just had a meeting with him.

Where?

There.

But what are you going to do about Maskhadov?

He needs to be persuaded to give up his powers until there is another presidential election in Chechnya.

Yes, but I haven’t been asked to do that, I’m just doing it on my own. Actually, there may not be an election.

But if we do, nevertheless, live to see an election, who would you put your own money on?

Khasbulatov or Saidullayev. They are a third force. Not on Maskhadov, not on Kadyrov. That’s what I think. After Nord-Ost it was me who organised negotiations between the Deputies of the Chechen Parliament and the Presidential Administration, with Yastrzhembsky.

Yes, that surprised a lot of people, when Isa Temirov together with other Chechen Deputies turned up openly in Moscow, spoke at the famous press conference in the Interfax news agency, and called on people to vote in the referendum. That was a blow against Maskhadov, although previously they had been for him. So you were behind that?

“I was,” he replies proudly.

And did you vote afterwards in the referendum yourself?

“Me? No.” He laughs. “I am from the Charto family teip. They call us Jews in Chechnya.”

Would it be accurate to say that the Nord-Ost tragedy was intended to have the role the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage-taking played [in 1995, a turning point which eventually led to the ending of the First Chechen War], only this time to end the Second Chechen War?

This is not an idle question. It is crucial. Khanpash has a finger in every pie of Russian politics. He knows everybody, he’s accepted everywhere. He’s capable of engineering all kind of twists and turns in the North Caucasus. If you need to bring Maskhadov into play, he will lead you to Maskhadov. You want to exclude Maskhadov? He can fix that too. So, at least, he tells me. But his profession, he says, is acting. He graduated from the Drama Faculty of Grozny University. Never mind that there never was any such faculty, and that he can’t remember the name of his acting teacher, this enables him to claim he is friends with Akhmed Zakayev. “We worked together in the theatre.” In the First War he acquired a video camera and started working in television. He accompanied Basayev on the Budyonnovsk raid, but was not imprisoned for taking part in it. On the contrary, he was amnestied in April 2000.

Where did you get the papers for the amnesty?

In the Argun Office of the Chechen FSB.

This is an important detail. The Argun FSB section has been one of the most dreaded throughout this war. At precisely the time Khanpash was receiving an amnesty from them, almost everybody else who fell into their hands was being dispatched into another world. Khanpash is the first person I have met who survived being in their hands, and he was even given a certificate of amnesty for his Budyonnovsk involvement.

Between the two wars Khanpash, as a “hero of Budyonnovsk,” became a leading consultant to President Maskhadov’s Press Service. He had his own television program on Maskhadov’s channel, The President’s Heart, later renamed, The President’s Path. That said, he was obliged to leave Maskhadov’s entourage even before the Second War, but when military operations resumed he was back, and again became a furious jihadist. It is astonishing, but right under the noses of the federal troops and every imaginable Russian intelligence agency, in the midst of heavy fighting when everybody else was running for cover, Khanpash managed to make a television program whose title can be roughly translated from the Chechen as, “My Homeland Is Where Jihad Is.”

Admittedly, neither then nor now did I believe that.

What do you mean? Your homeland is not where jihad is?

That was just the name of the program.

I heard Maskhadov has turned you away again recently?

Not Maskhadov, his representatives abroad, but I don’t trust them.

Rakhman Dushuyev in Turkey told me that he had received a cassette from Maskhadov saying the President no longer wanted me to call myself his representative, but I did not hear the cassette myself, or talk directly to Maskhadov. I recently had no trouble meeting Kusama and Anzor (Maskhadov’s wife and son) in Dubai. They accepted me. I ate and slept at their house.

Dubai, Turkey, Jordan, Strasbourg. You seem to be travelling all the time. How do you get visas?

I know all the Chechens. I travel to all countries and call on everyone to make peace and unite.

You travelled to Dubai from Baku?

Yes.

You turned up there after the terrorist act in Moscow in October and asked Chechens living there to help you? You told them you were one of the participants in the Nord-Ost hostage-taking who had survived, and now urgently needed contacts in the Arab world in order to escape pursuit?

How do you know that?

Chechens in Baku told me, and I read it in the newspapers. Your name is on the list of terrorists who were in Nord-Ost. Incidentally, are you suing over that?

No. Why should I? I just asked Yastrzhembsky, “How did that happen?”

What did he say?

“Just ignore it.”

The most recent upward spiral of Khanpash Terkibayev’s vertiginous political career in politics is indeed associated with the disastrous events of October 23–26, 2002, when the hostage-taking at the Nord-Ost musical caused the loss of many lives.

Had you known Barayev Junior for long?

Yes. I know everybody in Chechnya.

So did they have any explosives in there?

No, of course not.

After Nord-Ost, Khanpash really did become a confidant of Putin’s Presidential Administration. He held every authorisation he needed to enable him to move unobstructed from Maskhadov to Yastrzhembsky. He negotiated on behalf of Putin’s Administration with Deputies of the Chechen Parliament to get them to support a referendum. He obtained guarantees of immunity for the Deputies so they could come to Moscow. It was none other than Khanpash who, as leader of their group, took them to Strasbourg, to meet senior officials of the Council of Europe and the Parliamentary Assembly, where the Deputies did everything required of them at the behest of Dmitriy Rogozin, Chairman of the Duma Foreign Affairs Committee.

Naturally, the question arises, why did they choose Khanpash? What services had he rendered? How had he demonstrated his loyalty? Because without such proof he could not possibly have become involved in all this. We come now to a retelling of the most important part of our long conversation.

Khanpash appears to be the man for whom everybody involved with the Nord-Ost tragedy has been looking so diligently. He is the insider who made the terrorist act possible. Information in the possession of Novaya gazeta (which he doesn’t deny: he is vain), indicates that Khanpash was an agent sent in by the intelligence services.

He entered the building with the terrorists as a member of their unit. He claims he secretly enabled them to travel through Moscow and to the Nord-Ost venue itself. It was he who assured the terrorists that everything was under control, that there were plenty of corrupt people, that the Russians had again accepted bribes, as they did when high-ranking resistance fighters were able to break out of the encirclement of Grozny and Komsomolskaya. They needed only to make a lot of noise, he told them, and there would be a second Budyonnovsk, enabling peace to be secured. Then, when they had fulfilled their mission, they would be allowed to escape. Not all of them, but many. “Many” turned out to be only Khanpash himself.

He left the building before the assault began. He had a map of the Dubrovka Theatre Complex, something possessed by neither Barayev, who was in command of the terrorists, nor even, initially, by the special operations unit preparing the assault.

How come? Because Khanpash belongs to forces far higher in the militia and security hierarchy than the Vityaz and Alpha special operations troops who were risking their lives to storm the building.

Whether he was telling the truth about the map is not, actually, all that important. Khanpash would lie for a copeck, as his faked photographs demonstrate. Those who could confirm or deny certain details of his story, like where his firing position was, have, to all appearances, been eliminated or are less garrulous. Do I believe there was more than one agent sent in? I think it is entirely possible.

What matters is that if there was an insider operating in Nord-Ost, the authorities knew about and were involved in preparing a terrorist act. It doesn’t matter why. The main thing is that they (which section of them?) knew what was going on long before the rest of us did. They set up their own people for a terrible ordeal, knowing what was going to happen, fully aware that thousands would be permanently affected and hundreds killed or injured. The regime stage-managed another Kursk disaster. (Remember the messages sent by the unfortunate hostages from the occupied auditorium? “We are like a second Kursk. Russia has forgotten us. Russia does not need us. Russia wants us to die.” Many outside the hall were indignant and thought this completely hysterical, but in fact they were accurately describing the situation.)

The question remains, then, why was this done? Why were all those people killed six months ago?

The first step is to work out who was responsible. Who, within the regime, was in the know? The Kremlin? Putin? The FSB? – the classical triad of modern Russia?

The state authorities are not a monolith and neither are the intelligence services. It is definitely not the case that most of the officers working in the operational headquarters beside the Dubrovka Complex were only pretending to be trying to avert the tragedy, in the full knowledge that the whole thing was a put-up job. Most of them were entirely committed, like the Vityaz and Alpha Units, like the rest of us.

But if Khanpash was in there, there is no escaping the fact that some dark nook of the state authorities did know and was only going through the motions of sympathising during those three days of insanity. This completely alters the complexion of those events.

So who were the intelligence agencies who knew? Certainly not the special operations soldiers who carried out the assault. If they had known the depths of the duplicity, there might simply have been a repeat of 1993 when the units refused to mount an assault [on Yeltsin’s White House at the behest of the leaders of the anti-Gorbachev putsch], and the ending might have been completely different.

Neither was it the officers of the FSB and Interior Ministry, who planned the operation to rescue the hostages in all good faith. It was not they who infiltrated Khanpash into the terrorist group and subsequently fixed him up with a job.

Khanpash was not going to tell me who it was, but clearly the FSB and Interior Ministry were only acting out somebody else’s script.

In the Second Chechen War methods such as these have been used extensively by military intelligence. In the so-called death squads it is officers of the GRU, the Central Intelligence Directorate, who make the running. The extra-judicial killing of their fellow citizens there is their stock in trade. Against these blood-soaked leaders neither the FSB, nor the Interior Ministry, nor the Prosecutor’s Office, nor the courts can lift a finger. It is the practice of GRU units to exploit Chechen criminals and also their own victims, like those widowed by the death squads, as convenient fodder for achieving their aim of intimidating the whole of Russian society.

So was it the GRU, or someone as yet unknown? I have no answer, but it is vital that we should find out.

Why did those people die? Why such an unbelievable death toll of 129 lives?

That is what we get when we lift a corner of the curtain, when we hear the story of a double agent, a provocateur of our days so uncannily like Yevno Azef.*

People died, but the provocateur is alive and well. He is the political insider. He has his snout in the trough, looks good, and, most importantly, is still in business. In a few days’ time he will be going back to Chechnya. What will he be cooking up this time?

“I need 24 hours to meet up with Maskhadov,” he boasts.

“Just 24 hours?”

“Well, OK, two days.”

Khanpash is forbearing towards naive people like us.

December 22, 2003

The information agencies tapped it out: “Khanpash Nurdyevich Terkibayev has been killed in a car crash in Chechnya.” In the course of what we now know to have been his short life, the 31-year-old from Mesker-Yurt was to play many roles, of which the most important was unquestionably his complicity in the Nord-Ost hostage-taking in October 2002.

Who was Terkibayev? At first appearance, he was the last surviving witness from among the hostage-takers at the Dubrovka Theatre Complex. Officially listed as one of the terrorists, he claimed to have entered the building on October 23 last year as a member of Barayev’s unit. In reality, as Terkibayev himself told me, and as is indirectly confirmed, he was a turncoat, an informer who once inside first fed information to the secret services, then left the building shortly before the assault.

Khanpash Terkibayev had previously been a journalist for Maskhadov, presenting the President’s television program between the two wars. After Nord-Ost he was a member of President Putin’s Administration, on whose behalf he led a delegation of Chechen Deputies to the European Parliament in Strasbourg in April 2003. He would also show to anyone interested to see it his press pass as a special correspondent of the official newspaper Rossiyskaya gazeta. He was, in short, the servant of many masters.

The pinnacle of Terkibayev’s career was undoubtedly Nord-Ost. His was a horrifying tale which proved that Khanpash genuinely did move in the circles he described and that, accordingly, the atrocity was stage-managed by at least one of the Russian secret services. Simultaneously, another Russian secret service and several special operations divisions were combating it, culminating in the use of a secret chemical weapon against Russian citizens.

In May this year our newspaper published an interview with Terkibayev who at that time was still firmly in the saddle. From his revelations it was clear that the Nord-Ost tragedy was advantageous to the highly original regime known as “Russian managed democracy.”

What happened after our interview? We called on the team investigating Nord-Ost to question both Terkibayev and the author of these lines on the subject of Terkibayev. On one occasion the investigator actually did come to Novaya gazeta’s offices. In his record of the visit he wrote whatever he fancied, as is now common practice, a so-called free paraphrase. His interest in Terkibayev did not extend beyond the fact that, after our report, Basayev was threatening him for his treachery.

Terkibayev lived for much of this year in Baku, where things got so bad for him that he had no option but to move. Sooner or later Basayev’s people would have eliminated him, so he moved to Chechnya. This was a step born of desperation, putting his head in the tiger’s mouth. The federal forces now had no time for him, and he had no other source of support. The car accident followed.

What is the most important aspect of this? Historically, as everybody knows, double and triple agents end up getting murdered. For us, however, this only makes things worse. Terkibayev never was questioned, and accordingly one further fragile link in the chain leading to the truth about Nord-Ost has been broken. He took with him information which ought to be known to everyone in Russia, the answers to fundamental questions about Nord-Ost to which we, thanks to the efforts of those at the top of the political pyramid, have no answers. Who supported Barayev’s unit in Moscow? (We are not talking here about corrupt officials issuing visas, although, ironically, some are facing trial this very week.)

How did Barayev’s people get into Moscow at all? How were preparations for a terrorist attack in Moscow made? Who was Terkibayev’s controller in the secret services, and in which one? Why was there an assault? Why were negotiations which had some prospect of success in getting the hostages released terminated? Who was involved in taking such criminal decisions?

If we reduce these questions to their lowest common denominator, they indicate something we all suspect but cannot prove: that this was a managed act of terrorism in which Barayev was manipulated, and in which the female suicide bombers in black who accompanied him were dupes.

One important detail for anyone interested in receiving accurate information is that not only was Terkibayev not questioned by the members of the official Nord-Ost inquiry, he was even ignored by the members of the Public Commission of Inquiry, which does exist, although it is so inactive that it might as well not.

The timing of the car accident is also revealing: Terkibayev might have been about to open his mouth. The CIA was taking an interest in him. CIA agents were (quite properly) conducting their own inquiry into the death of an American citizen who had been among the audience, and had been signalling that Terkibayev was of interest to them as a source of evidence. (This may also have been a reason for Terkibayev’s move from Baku; in Baku he was accessible to the CIA, while in Chechnya he was probably not.)

Where does that leave us? “The agent must not be allowed to talk,” and Terkibayev has been duly silenced.

That is the main surmise about the causes of the car accident. Nobody will ever be able to prove that it was a genuine accident. Even if it was, nobody would believe it.

More generally, in the now eternal absence of Terkibayev the unquestioned and liquidated, I personally will never believe that the secret services are not involved in organising terrorist acts. They have done everything they could to torment me with the belief that they are. If there is another hostage-taking, the first question that will spring to mind will be, who is behind it? Which of those supposed to protect us are actually orchestrating the terrorists?

January 19, 2004

At the end of a two-hour meeting [between the head of the official investigation into the Nord-Ost hostage-taking and victims and relatives], I had to intervene and remind Mr Vladimir Kalchuk about the truth of the Terkibayev affair.

His reaction was bizarre. He told me to get lost and to stop writing to him, otherwise he would “hint” to the Nord-Ost victims that my son’s mobile telephone number had been discovered in the memory of the phone the terrorists were using, “and then we will see what they will do to you. They may well be interested to know exactly what kind of personal links you have with the terrorists, you and your son …”

In view of this, I will have to persist with my reminders to Mr Kalchuk. Firstly, negotiations needed to be conducted during the siege, which I did. Secondly, the person I chose to help me was indeed my son, Ilya Politkovsky, and help me he did, courageously, conscientiously and openly trying to save, among others, the life of his close friend, Ilya Lysak, a musician in the Nord-Ost orchestra. Lysak was inside the occupied auditorium and used his personal connection with my family in order – equally courageously and heedless of the possible consequences – to facilitate negotiations. It was he, who today is still extremely ill, who handed his mobile telephone to the terrorists, and they used it to talk to me and my son, to agree the exact time I would enter the occupied building. They also used it to talk to Sergey Yastrzhembsky, the President’s Aide.

I am sure the overwhelming majority of people would have done the same in the circumstances. Apparently the individual entrusted with leading the inquiry into the Nord-Ost tragedy would not.

* Date of posting on the Novaya gazeta website.

* A Tsarist police spy who organised deadly terrorist acts, even assassinating the Tsar’s uncle to entrap his colleagues in the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

Anna, starting out

Raisa and Stepan Mazepa with daughters Anna and Elena, New York, 1962

At Moscow School No. 33, 1971

The three schoolfriends: Masha, Anna, and Elena

Anna graduates from secondary school, 1975

Marriage, April 1978

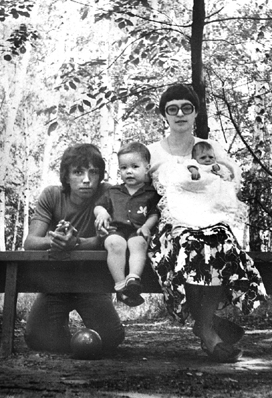

A family: Alexander, Ilya, Anna and Vera, summer 1980

The children. Anna’s favourite photograph

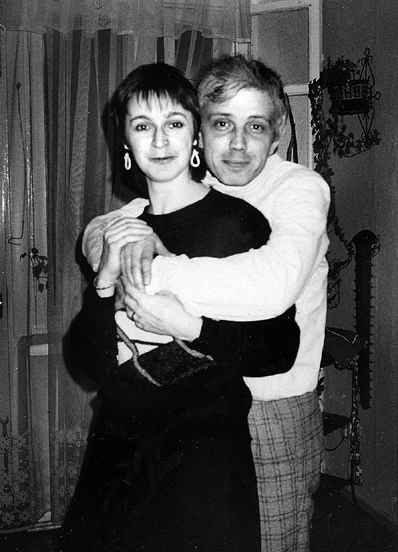

At a party with her husband Alexander, early 1990s

With Alexander and Martyn the Doberman, late 1990s

With her sister Elena, London, 2002

On the flight to Tura, where a small delegation from Novaya gazeta unveiled a monument at the geographical centre of Russia, December 2000

Vnukovo Airport, Moscow, February 2001, returning after her detention by Russian troops

The Nord-Ost siege. Anna and others take water and juice to the hostages, Moscow, 25 October 2002

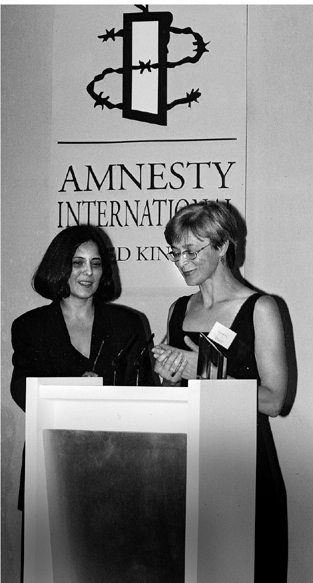

Presentation of the Global Award for Human Rights Journalism by Amnesty International, London, July 2001

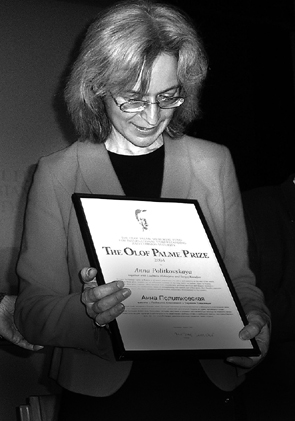

Olof Palme Prize ‘For Courage and Composure While Working in Difficult and Dangerous Conditions’, Stockholm, January 2005

The last image of Anna Politkovskaya, captured by a supermarket CCTV camera, 7 October 2006

March 2002