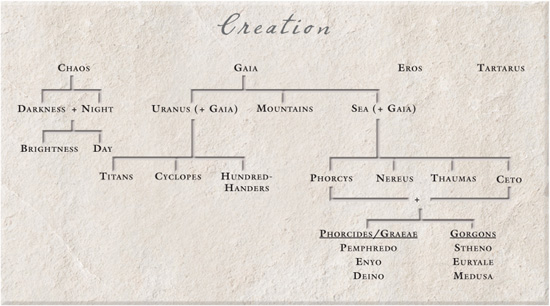

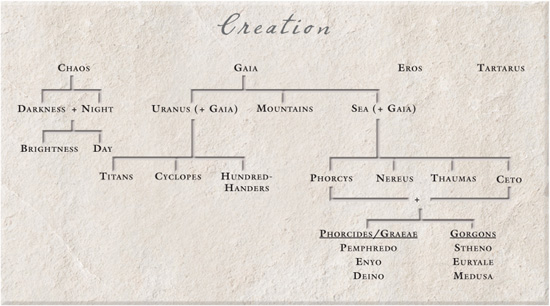

In the beginning, there was … nothing. Picture it as a gap, a void filled with swirling movement, not emptiness. There was nothing that held together, nothing distinct, nothing measurable by any form of measurement. There were no borders or limits, but within the void appeared Gaia, the Earth, just as when building a house the foundation comes first.

And in the depths at the lowest extent of deep-rooted Gaia was Tartarus, the place of punishment, the world beneath the world. Earth and Tartarus emerged spontaneously, but Love is the fundamental creative force. Love, coeval with Gaia, governs the subsequent stages of creation.

Gaia and Tartarus were surrounded by the darkness of night, but Night blended with Darkness and bore Brightness and Day. And so time came into being, measured by the onward-rolling day and night. By herself Gaia, the Earth, bore Uranus, the Heaven, to cover her completely. Heaven lay with Earth, and she conceived and bore Ocean, the water encircling the continents of Earth, and Tethys, the waterways within the continents of Earth.

From the prolific mingling of the waters the earth was clothed, and from the mingling of Earth and Uranus there emerged, among many other children, the Titans, twelve in number: Cronus and Rhea, Hyperion and Theia, Iapetus (the father of Prometheus), and the rest of the gods of old. Their names now are mostly unfamiliar, for these were the days of yore. Under the rule of Cronus the world was of a different order, and it is not easy to comprehend it, except to say that it was primitive.

Wide-shining Theia bore for Hyperion the blazing sun, the radiant moon, and the rosy-fingered light of dawn, which gently fills the sky even before the sun rises. Helios the sun-god drives his golden chariot from east to west, and sails in a golden vessel each night on Ocean back again to the east. Helios had a son called Phaethon, the gleamer, who was allowed by his father, in a moment of weakness, to drive his chariot for one day, much later in the earth’s history. But none apart from Helios can control the blazing chariot drawn by four indefatigable steeds, and Phaethon hurtled to earth in a ball of flame. Much of the earth’s surface was scorched and became desert, and the skin of those dwelling there was burned black for all time. Phaethon’s sisters were turned into trees, and the heavy tears of grief they shed for their brother solidified as amber.

Disaster struck when Helios allowed Phaethon to drive the Sun chariot for a day.[3]

In later times, sisters Selene, the moon, and Eos, the dawn, fell in love with mortal men. Endymion was a shepherd, who slept each night in a mountainside cave in Caria. Selene caught a glimpse of him from on high, and as her pale gleam fell on his features she fell too, such is the force of love’s attraction. Every night she lay with him while he lay cradled in sleep, not knowing that his reality was stranger than any dream. Selene loved him so much that she could not bear the thought that he would age and die. She implored Zeus to let him remain as he was, and the father of gods and men granted Endymion eternal youth and eternal sleep—except that he awoke each night when Selene visited him to satisfy her longing.

Eos enjoyed numerous affairs, for once she went to bed with Ares, and in jealous anger Aphrodite condemned her to restless ardor. One of those with whom she fell in love was the proud hunter, Tithonus, as handsome as are all the princes of Troy; and she begged Zeus that her mate should live forever.

Zeus granted her wish, but the love-befuddled goddess had forgotten to ask also for eternal youth for her beloved. In the days when their passion was new, the graceful goddess bore Memnon, destined to rule the Ethiopians for a time and meet his end before the walls of Troy. But as the years and centuries passed, Tithonus aged and shrank, until he was no more than a grasshopper, and Eos shut him away and loved him no more. If asked, he would say that death was his dearest wish.

And Helios too dallied for a while with a mortal maid, Leucothoe by name. He thought of nothing but her, and for the sake of a glimpse of her beauty he would rise too early and set too late, after dawdling on his way, until all the seasons of the earth were awry. The god had to consummate his lust, or the chaos would continue. He appeared to her as her own mother, and dismissed her handmaidens, so that he could be alone with her. Then he revealed himself to her; she was flattered by his ardent attention and put up no resistance. But when her father found out he buried her alive by night, so that the sun might not see the deed, and by the time morning came there was nothing he could do to revive his beloved. But, planted as she was in the soil, he transformed her into the frankincense bush, so that her sweet fragrance should please the gods for all time.

Now, Uranus, the starry sky, loathed his children—not just the twelve Titans, but the three Cyclopes, one-eyed giants, and the three monstrous Hecatonchires, each with fifty heads and a hundred hands. Every time a child was born, Uranus seized it and shoved it back inside its mother’s womb, deep in the darkness of Earth’s innards.

In the agony of her unceasing labor pains, Earth called out to the children within her, imploring their help. But they were still and cowered in fear of their mighty father, all except crafty Cronus, the youngest son. Only he was bold enough to undertake the impious deed. He took the sickle of adamant that his mother had forged and lay in wait for his father. Soon Uranus came to lie with Earth and spread himself over her completely. Cronus emerged from the folds where he was hiding, wielding his sickle, and with one mighty stroke he sliced off his father’s genitals and tossed them far back, over his shoulder.

After Cronus defeated his father Uranus, his siblings were freed from Gaia’s tortured womb.[4]

The blood as it scattered here and there, and spilled on the soil, gave rise to the Giants and the Furies, the ghouls who sometimes, with grim irony, are called the Eumenides, the kindly ones. They protect the sacred bonds of family life, and hunt down those who deliberately murder blood kin. They drink the blood of the victim and hound the hapless criminal to madness and the blessed release of death. They are jet black, their breath is foul, and their eyes ooze suppurating pus.

But the genitals themselves fell into the surging sea near the island of Cythera and were carried on currents to sea-girt Cyprus. From the foam that spurted from the genitals grew a fair maiden, and as she stepped out from the white-capped waves onto the island grass grew under her slender feet. The Seasons attended her and placed on her head a crown of gold, and fitted her with earrings of copper and golden flowers; around her neck they placed finely wrought golden necklaces, that the eyes of all might be drawn to her shapely breasts.

Her name was Aphrodite, the foam-born goddess, and there is none among men and gods who can resist even her merest glance. She is known as the Lady of Cythera and the Lady of Cyprus; and henceforth Love became her attendant.

Cronus, the youngest of the children of Uranus, usurped his father’s place as ruler of the world—but inherited his fear, the typical fear of a tyrant. For his parents warned him that he in his turn would be replaced by one of his sons. Each time, then, that a child was born to Rhea, his sister-wife, he swallowed it to prevent its growth. Five he swallowed in this way: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. Pregnant once more, Rhea appealed to her mother Earth, who promised to rear the sixth child herself. And so, when her time came, Rhea went and bore Zeus deep inside a Cretan cave, while to Cronus she gave a boulder, disguised in swaddling clothes, for him to swallow.

Each time Rhea bore a child to Cronus he consumed it.[5]

In the cave on Mount Dicte, the infant Zeus was fed by bees and nursed by nymphs, daughters of Earth, on goat’s milk, foaming fresh and warm from the udder. Young men, mountain-dwelling Curetes, wove outside the cave a martial dance and clashed their spears on their shields to cover the sound of infant wailing. As he grew older, Amalthea, the keeper of the goat, brought the boy all the produce of the earth in an old horn.

And so the mountains of Crete are sacred ground, and even now the Cretans summon the god by means of dance, and he replenishes their hearts and their crops. And Zeus flourished and grew in might, but in his heart he nurtured his mother’s dreams of vengeance.

Zeus laid his plans with skill and cunning—with his witchy consort Metis, whose name means “skill” and “cunning.” There was nothing this shape-shifting daughter of Ocean and Tethys didn’t know about herbs, and she concocted for Zeus a powerful drug, strong enough to overcome even mighty Cronus. Together, and with the help of grandmother Earth, they drugged Cronus with narcotic honey. And while he was comatose they fed him the emetic.

The result was exactly as intended: Cronus vomited up in order first the boulder, still wrapped in moldering rags, and then Zeus’ brothers Poseidon and Hades, and then his sisters Hera and Demeter, and finally Hestia, oldest and youngest. For the forthcoming war—for war was inevitable—these were Zeus’ bosom allies. Cronus, for his part, was joined by all his fellow Titans and their offspring, with the notable exception of Themis, for right was on Zeus’ side and victory was destined to be his.

Zeus made his headquarters on Mount Olympus in northern Greece, while Cronus chose Mount Othrys, a little to the south. This was the first war in the world, and there has been none like it since. For ten years the conflict raged ceaselessly and without result; for ten years earth and heaven resounded and shook with the frightful din of battle. Neither the Titans nor the Olympians could gain the advantage.

Long ago, in the early days of the war, Prometheus, resident on Olympus with his mother Themis, had offered Zeus some advice. Still imprisoned deep within Gaia were the Hundred-handers and the Cyclopes. Zeus considered them too monstrous, too hard to control, but now he was desperate to break the deadlock. He extracted from them the most solemn oath, that if he released them and armed them, they would be his grateful allies. The former could hurl boulders the size of hills with their hundred hands, while the latter, cave-dwelling smiths, would create for Zeus his weapon of choice, the thunderbolt—the missile that accompanies a flash of lightning. And at the same time they made weapons for his brothers in their forge: a trident for Poseidon and a cap of invisibility for Hades. The earth, the seas, and the heavens resounded as hammers met anvils; the sparks were as the stars in the sky.

Now Zeus sallied forth from Olympus, the acropolis of the world, and confronted the enemy face to face. Hurling lightning and thunderbolts in swift succession, he overwhelmed the enemy. The land blistered and blazed with fire and the waters boiled; steam and flame rose and filled the sky. It sounded as though Earth and Heaven had collapsed into each other with a ghastly crash. It looked as though all the subterranean fires of the earth had boiled up from the depths and erupted on the surface of the earth.

The heat of Zeus’ missiles enveloped the Titans, and the blazing lightning blinded them. Meanwhile, Aegicerus, half goat and half fish, the foster brother of Zeus from the Cretan cave, blew a trumpet blast on his magical conch-shell and sowed panic in the Titan ranks. And now the Hundred-handers played their part. As thick and fast as hailstones, huge boulders rained down on the Titans, darkening the sky and crushing even Cronus. Overcome, the Titans were bound and sent down to the gloom of Tartarus, from where nothing and no one can escape but through the pardon of the Ruler of All. It is like a gigantic jar, with walls of impenetrable bronze, and its entrance is stopped with three layers of darkness and guarded by the Hundred-handers. It is the place of uttermost punishment, lying as far beneath the earth as the heaven is above it. Nine days it would take a blacksmith’s anvil to fall from the edge of heaven to the earth, and a further nine days still to reach Tartarus. But easy though the descent may be, the return journey is impossible.

And so the sons of Uranus mostly pass from our knowing, for no bard sings in praise of the defeated. The noble but misguided Atlas, for allying himself with his uncle Cronus, is forever compelled to shoulder the tremendous burden of the heavens. The female Titans—Leto, Memory, Tethys, Phoebe, Themis, Theia, and Rhea—were allowed to remain under the upper sky, honoring the will of loud-thundering Zeus. Leto bowed to his desire and on the sacred island of Delos bore him the twin deities Artemis and Apollo; Memory lay with Zeus and from her were delivered the divine Muses, nine immortal daughters, patronesses of culture and all the arts; and Themis gave birth to the three reverend Fates, whom the unfortunate castigate as blind hags.

The Fates, Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, determine the length of a life.[6]

Among the Muses who dwell on Mount Helicon, the province of Calliope is epic poetry; of Clio, history; of Urania, science; of Euterpe, the music of the pipes; of Melpomene, tragedy; of Thalia, comedy; of Terpsichore, lyric poetry and dance; of Erato, love poetry; and of Polymnia, sacred music.

Sweet Muses, delighting in song and dance, but they know also that true sadness may inspire poets to their greatest work, and like all deities they are proud of their domain. The nine daughters of Pierus of Pella challenged the goddesses to a singing contest, and were turned into chattering magpies for their presumption when they lost. And once Thamyris of Thrace, the foremost musician of his age, desired to sleep with the Muses, all nine; and his eyes, one blue, one green, sparkled at the thought. The Muses agreed—if he could demonstrate his superiority to them as a musician. He lost the contest, and they took his eyes from him along with his talent. There is a lesson here for a pious man, if he takes the time to ponder it. It’s a fool who vies against the immortals.

Of the three Fates, Clotho sits with her spindle and whorl, twisting and spinning out the thread that is assigned for every creature from birth to death. At her left hand, her sister Lachesis, the dispassionate apportioner, marks the length of the thread. By their side stands the implacable Atropos, ready to cut the thread at the chosen point and bring a life to an end. Just as the Fates determine the length of mortal life, so also the ancient goddesses decide how long prosperity, health, and peace are to last. And know this: if the length of a life is already determined, men must act with courage, for they will die anyway when it is their time.

The Titans were defeated, but still there were challenges to Zeus’ rule. Not long later—but after many centuries of human time—he had to face the Giants, born of the blood of Uranus. The Giants had various forms and features, just as do the children of men, except that in place of legs they had the sinuous strength of huge snakes, and they were wild and shaggy all over. They were a force for disorder and chaos, rapists, thieves, and murderers, and they could not be allowed to co-exist with the new order. Things came to a head when the Giants rustled the cattle of Helios, the sun-god. It was the last straw. War was declared, and the uncouth and unkempt Giants stormed heaven with boulders and burning brands.

There were so many of them that Zeus could not handle them alone, and for the first time the gods worked together as a team. Even so, they could not prevail against the hostile mob. For it was foretold that the Giants could be defeated only by a force that included a mortal. But no mortal then alive would last more than an instant against the Giants: this was not yet the Age of Heroes. It would be like pitting a candle flame against a tempest. And the Giants, knowing this, were sure of their final victory.

Zeus concocted an awful plan. The only human ally he wanted was Heracles, but Heracles had not yet been born. Zeus reached into the future and pulled Heracles back through time to help against the Giants. To Heracles, it seemed a lucid dream, one never to be forgotten—a dream filled with fire and pain and awesome deeds. In desperation at Zeus’ cunning, Gaia sought a unique herb that would give her foul children true immortality, even against Heracles. But Zeus, learning of her quest, forbade the sun and the moon and dawn to shine, so that Gaia could not find the plant and Zeus plucked it for himself.

The greatest of the Giants was Alcyoneus, who could not be killed while he was in touch with the land from which he had sprung, the Pallene peninsula. Heracles shot Alcyoneus with his bow, but no sooner had the Giant crashed to the ground than he sprang up again, reinvigorated. Heracles was at a loss: again and again he shot him, and every time the same thing happened. Then wise Athena told him Alcyoneus’ secret, and summoned indomitable Sleep, and the giant fell into a deep slumber. While he was asleep, Heracles laid hold of him and dragged him off Pallene. The Giant awoke, briefly struggled, and breathed his last.

But Porphyrion, equal in might to his brother Alcyoneus, and the leader of the Giants, overwhelmed the goddess Hera and began to rip off her clothes, desiring to take her against her will. Zeus stunned the savage Giant with a thunderbolt, and Heracles finished him off with his bow. Dionysus, surrounded by wild animals and riding into battle on a donkey whose braying cowed his enemies, smote Eurytus with his thyrsus staff, while foul Clytius fell before the flaming brands of the dread witch-goddess Hecate. Mimas died horribly, his body boiled by molten metal poured from Hephaestus’ crucible.

Fearsome Athena buried Enceladus under Sicily, and then turned to Pallas; she flayed him alive and wore his raw skin, sticky with blood, as a shield. Poseidon broke off part of the island of Cos and crushed Polybotes with it. Hermes, wearing Hades’ cap of invisibility, killed Hippolytus, and Artemis did away with Gration. Apollo shot out the left eye of Ephialtes, while Heracles’ arrow lodged deep in the other. The Fates, wielding massive clubs of bronze, crushed the skulls of Thoas and fierce Agrius. The rest were scattered by Zeus’ thunderbolts and, to fulfill the prophecy, shot down by Heracles as he raced after them on his chariot. Gaia implored Zeus for the lives of her children, but he was not to be swayed. There should be none to challenge him.

“The Fates, wielding massive clubs of bronze, crushed the skulls of Thoas and fierce Agrius.”[7]

After bitter war, peace came to Olympus. For a brief while, the heavens were untroubled, and Zeus began to make provisions for his newly acquired realm. But then there arose a new contender for the throne of the world. Gaia was saddened by the defeat and death of her offspring, the Giants, born of the blood of Uranus. But she had to admit that Zeus was proving himself a worthy king. She devised for him one final test, so that all might see his kingly qualities, or his humiliation.

Out of her most hidden depths Earth heaved forth a terrifying monster. A hundred snake-heads sprouted from Typhoeus’ shoulders, and the forked tongues flickering from their mouths matched the fiery flashes from two hundred eyes. But the sounds the gigantic creature emitted were the worst: not just the hissing of snakes, but the baying of hounds, the bellowing of bulls, and the roar of lions; not just recognizable and comprehensible sounds, but sounds that were never heard before or since, that had meaning, but no meaning anyone could grasp. The part-human, part-serpentine body of the beast was as strong as a mountain, and he advanced on Olympus with his confidence high, ready to institute a new and terrible order for gods and men.

At the sight of the monster all the gods fled from Olympus to Egypt and disguised themselves as innocuous animals. But Zeus came down from the high mountain to meet the challenge. Had there been onlookers, it would have seemed as though the land and the sea were consumed by a horrific storm. Swollen purple and black clouds shrouded the battle, and all that could be seen were flashes of fire and lightning, and the billowing and surging and whirling of the clouds. The noise was abominable—the crashing of the thunder, the crack of lightning, the hiss of flames extinguished in the sea, the cries of pain from Typhoeus, magnified a hundred times by a hundred howling heads.

Zeus attacked without mercy, blinding the creature with fire and shriveling his heads black with lightning. Typhoeus leapt into the sea to extinguish the flames that erupted all over his body, but Zeus smote him again and again, until the rocks of the battlefield melted like wax, the sea boiled, and the tormented, smoking ground shook and cracked open black and gaping maws. And Zeus finally hurled the monster into the greatest of these chasms all the way down to Tartarus, and piled Mount Etna on top and pounded its roots deep into the ground, to contain Typhoeus forever. Only once in a while is he able to wriggle a bit, and then mortal men, little that they know, say that the Sicilian volcano is rumbling.

But the sounds of the volcano are no more than faint echoes of his voices of old, and its power the merest sliver of Typhoeus’ former strength. All he left behind were his children, the winds of destruction and the many-headed monsters: Cerberus, the hell-hound that guards the entrance to the underworld, with his three savage heads and tails of venomous serpents; the nine-headed, marsh-dwelling Hydra; two-headed Orthus, protector of the red cattle of Geryon; and the Chimera, whose foreparts were those of a lion, but her tail was a living serpent, and a goat made up her trunk, and all three heads hissed and roared and spat with indiscriminate fury.

Zeus had cleared the world of the most potent forces of disorder and chaos, a burden that would also fall on some of the heroes of later time, in proportion to their lesser abilities. By force of arms, he had confirmed his right to the high, golden throne of heavenly Olympus.

In order to ensure ongoing stability, every major domain of life on earth was given into the care of one of the gods, so that each had his or her unique province and none should be dissatisfied. Above, there spread the wide heavens; below, the misty underworld stretched down to Tartarus, the place of woe; between lay the surface of the earth. Great Zeus, the wielder of the thunderbolt and lightning, took for himself the heavens and the halls of Olympus, but treated his two brothers as equals. Dark Hades became lord of the underworld, while horse-loving Poseidon gained the surface of the earth, and especially its waters.

And so Zeus is the cloud-gatherer, the hurler of thunderbolts, the shining lord of sky and weather. Men pray to him for many things, for all the other gods obey his commands; but especially they pray for sufficient rain to impregnate the earth, so that their flocks fatten and their crops multiply.

From high Olympus he looks down on the earth and ponders its fate. Effortlessly, he raises a man up or brings him low, makes the crooked straight and humbles the proud. The earth trembles at his nod. If he descends to earth, he comes as a flash of lightning, and the scorched ground where he alights from his chariot is sacred. His majesty is second to none, and he may also appear as a soaring eagle, aloof and magnificent. He speaks to mortal men through the rustling of his sacred oak at Dodona; the oracle at Olympia is his, and the four-yearly games there are sacred to him.

Men think of Poseidon as the trident-bearing lord of the sea, and they pray to him for safety, for they and their craft are puny, and he is mighty and of uncertain temper. But he is also the earth-shaker, the maker of earthquakes, when the very land seems to ripple like the sea and yearn to be water. And he delights in horses, for a free-running horse flows like a mighty wave, with muscles gleaming and tail streaming. All he has to do is stamp a hoof, or strike a blow with his trident, and sweet water gushes from solid rock. His wife is Amphitrite, who dwells in the booming of the sea and the whisper of the sea-shell, though he had children by many another nymph and goddess too. Poseidon drives over the sea in a chariot drawn by horses with brazen hoofs and golden manes, and at his approach the waves die down and the sea gives him passage.

Poseidon’s realm is the sea, but he is also the earth-shaker, and patron of the horse.[8]

What can be said about Hades? No living man has ever beheld his face, and the dead do not return from his mirthless domain. He is the invincible one, for death awaits all; with his staff, he drives all in their time into the echoing vaults of his palace. No one knows for sure where the entrance is to his subterranean realm. Some say that it is in the far west, where the sun goes down to darkness; others that certain caves or chasms conceal an entrance.

Through the gloom of his underworld realm flit the feeble remnants of men of old, pale spirits, gibbering and forlorn, and dust and mist is all their food; and the River Styx, never to be re-crossed, surrounds the domain of Hades, as Ocean surrounds the continents of the earth and the Milky Way surrounds the heavens. Charon the ferryman, dreaded by all, transports the dead across the river to their eternal home, if they bring the coin to pay him. Otherwise, they remain as pale ghosts, whimpering feebly on the banks of the river and imploring all-comers for a proper burial; but those who come are only the dead themselves, and can help no more.

This is the doom that awaits us, except for the few, righteous or unrighteous. Those whose brief dances have pleased the gods are allowed to dwell forever on the Isles of the Blessed, or in the Elysian Fields, where temperate breezes gently stir meadow flowers, nurtured by sweet springs and showers. But warmongers and tyrants, murderers and rapists, perpetrators of all foul and abnormal crimes against the gods or hospitality or parents, are cast into the depths of Tartarus and suffer endless torment. Hades is the lord of the dead, but his lady Persephone shares his powers, and the souls of the dead are judged by three stern judges: the two wise sons of Europa by Zeus, Minos and Rhadamanthys of Crete, and Aeacus, son of Zeus and Aegina. And Hades is also Pluto, the giver of wealth, because all crops arise out of the under-earth, and he bears rich minerals deep in his secret places.