Although the Allies had established themselves along the Normandy coast and were in the process of reinforcing the beachhead, the Germans had not yet thrown in the towel. They continued to counterattack along the entire Allied front, looking for a soft spot to exploit. In nearby Bréville, to the north of 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion’s position, the Germans focused enormous efforts. The town had been under constant attack since 7 June. The situation was critical and additional artillery support was called in from the divisional artillery of 3rd British Infantry Division to break up substantial German infantry and armour attacks.

The extra weight of steel lashed and tore at the German attackers, but they would not relent. Sensing a weak seam, the enemy seemed more determined than ever to smash a hole in the Allied line. By 10 June, the Germans had seized most of Bréville. That night, Sherman tanks from a squadron of the 13/18 Hussars and 5th Battalion, 51st Highland Division, arrived to strengthen the Allied line, which was part of the 6th Airborne Division’s sector. The next morning, after a preliminary bombardment, the Highlanders launched an attack against the Germans, who had established well-entrenched positions in and around Bréville. The attack failed dismally. As soon as the Highlanders stepped off for the attack, German mortar rounds started raining down on them. Those not wounded or killed by the flying shrapnel were cut down by the German MG 42 machine guns that swept the ground leading to their positions.

FROM THE WEAPON LOCKER

MG 42

The MG 42 is the shortened name for the German 7.92 mm Maschinegewehr 42 (machine gun 42), which was the standard machine gun for the German Army during the Second World War. It entered service in 1942 and replaced the MG 34 general purpose machine gun that was adopted in the 1930s. The very portable MG 42 weighed 11.6 kilograms when fired from its bipod. For sustained fire application, the Lafette 42 tripod was used, adding another 20.5 kilograms to the weight of the weapon system. For sustained fire operation the optimum operating crew of an MG 42 was six men. There was a gun commander; the No.1, who fired the gun; the No.2, who carried the tripod; and the Nos.3, 4, and 5, who carried ammunition, spare barrels, entrenching tools, and other equipment. Due to manpower constraints, the crew of the MG 42 was often cut down to just three members: the gunner, the loader, and the spotter.

The MG 42 earned an unrivalled reputation for its reliability, durability, simplicity, and ease of operation. However, its greatest strength was its amazing rate of fire. It had one of the highest average rates of fire of any single-barrelled man-portable machine gun of the time. It fired approximately 1,200 rounds per minute, twice the rate of the British Vickers machine gun and the American Browning light automatic rifle, which both fired around 600 rounds per minute. The MG 42’s high rate of fire gave it a distinctive firing profile that sounded like ripping cloth. Allied soldiers gave it the nickname “Hitler’s buzzsaw.” German soldiers called it Hitlersäge (Hitler’s saw). British troops often called it the Spandau machine gun based on the manufacturer plates naming the district of Berlin where many were produced.

The tanks fared no better. As the first three Sherman tanks clanked down the wooded path towards the enemy positions, they were quickly destroyed by a German self-propelled gun that ambushed them from the flank; its first shot tore the turret off the leading Sherman tank. As the two other Shermans that were following began to rotate their guns to engage the enemy armour, they too were brewed up. In less than a minute the Allies had lost three more tanks. In the end, all that the attack achieved was heavy losses — the battlefield was littered with the burning and smouldering hulks of Sherman tanks and the bodies of British infantrymen and paratroopers.

Buoyed by this success, the Germans quickly decided to capitalize on what they perceived as an advantage. The enemy artillery and mortar fire quickly started again. The deadly barrages were immediately followed by massive infantry attacks, supported by tanks and self-propelled guns. Artillery and mortar shells hammered the Allied positions, forcing the defenders to stay hunkered down and allowing the German soldiers to approach the Allied trenches as close behind the curtain of fire as possible without being fired at. German Mk IV tanks and self-propelled guns appeared on the high ground and lent direct-support fire to the attack by hurling explosive shells at any pocket of resistance in the Allied line. In quick succession, they destroyed all of the defenders’ anti-tank guns as well as nine Bren gun carriers.

By late afternoon on 12 June, the Germans, refusing to ease the pressure, were continuing their attacks. The situation deteriorated to the point that an enemy breakthrough in the Bréville area was imminent. in the Bréville area was imminent. The state of affairs had become critical. If the Germans were successful in breaking through at Bréville then the entire 6th Airborne Division sector, which was already dangerously weak, would be compromised and their ability to contain future German attacks would be doubtful. The Division was now in a critical state — its manpower was already stretched to the limit and reinforcing the sector meant weakening another.

By that time, Major-General Gale, the 6th Airborne Division commander, visited the front lines to assess the situation first-hand. Even though the initial and subsequent German attacks had been contained, he quickly realized that the sector was the weakest link in the 6th Airborne’s defensive front. This was not surprising. From the outset, Brigadier James Hill, the commander of 3rd Parachute Brigade, had warned him about the weak state of defence at Bréville and its surrounding areas. Immediately after the D-Day drop, he had urged Major-General Gale to take whatever action was necessary to remove the Bréville menace. Now Brigadier Hill would have his chance to solve the problem; and, the Canadians would help.

DID YOU KNOW?

“The New Infantry March”

Airborne we fly the sky

Paratroopers we do or die

Speed troops like the wind we go

We’re sons o’guns! We’re sons o’guns!

We won’t take “no” for an answer,

Can’t stop those paratroops,

Hurdling down into the fray.

Oh! It’s not the way it used to be,

A bigger and better infantry comes in by air today!

It used to be the infantry did nothing but march all day,

Dusty guys, with mud in their eyes,

Went slugging along the way.

But times have changes and now we range

The sky and sea of blue,

We ski a bit or maybe we’ll hit the silk of a parachute. OH ! ! !

Amazingly, Brigadier Hill was recuperating from a serious friendly fire injury he had sustained on D-Day. After the parachute drop, as he was marching towards his objective area, Allied aircraft conducted a bombing run and accidently attacked their own troops. Hill and his party quickly sought cover in shell holes, but a number of the paratroopers were killed and wounded. Hill suffered a deep wound to his buttocks, but he refused treatment until he had established the defence of his Brigade area. Only days later would he allow the Brigade surgeon to operate on him to sew up his wound. Despite his recent surgery and healing wound, Hill realized the situation was desperate and decided to take matters into his own hands.

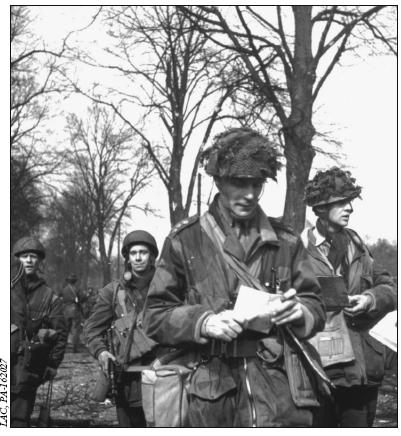

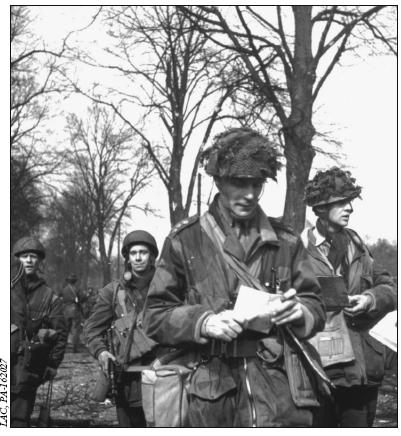

Brigadier James Hill, the well-respected commander of 3 Parachute Brigade, checks his map during the breakout phase of the Normandy Campaign.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

Brigadier James Hill

Brigadier James Hill was born 14 March 1911. He attended Sandhurst Royal Military College from 1929–31 and finished second in his class, winning the Sword of Honour and the Sword of Tactics. He was also the Captain of Athletics. Upon graduation, James Hill joined the Royal Fusiliers, one of England’s most esteemed infantry regiments. Hill left the military in 1936, but rejoined his old regiment in 1939 when war broke out. During the Battle of France in 1940 he was on staff with Lord Gort’s command post and barely escaped from the evacuation beach at Dunkirk, boarding the last Destroyer out.

Hill was awarded the Military Cross for his actions in France. In 1941 he joined the newly established British Airborne forces. By 1942 he was appointed commanding officer of the 1st Parachute Battalion and fought in North Africa, where he was severely wounded. He earned the Distinguished Service Order and the French Legion of Honour for his gallantry in North Africa.

Upon return to active duty he was promoted to brigadier and appointed Commander of 3rd Parachute Brigade in the newly formed 6th Airborne Division. At 31, he was the youngest brigadier in the British Army. Upon completion of hostilities, Hill became military governor of Copenhagen. When that duty was completed he retired from the military and returned to his family’s shipping business.

Brigadier Hill rushed over to the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion Headquarters to gather all available personnel. Although the Canadians were also under heavy attack, the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Bradbrooke, felt he could hold off the enemy well enough in his sector. He released his reserve force to the Brigadier.

The word was quickly passed on. Captain John P. Hanson and approximately 40 paratroopers from “C” and “HQ” Companies assembled at the Battalion headquarters to receive their orders. Brigadier Hill, a charismatic commander who always led by example, simply smiled at the men and said, “Come along Chaps, nothing to worry about.” He then led his ad hoc force to Bréville in an attempt to stop the German breakthrough.

FROM THE WEAPON LOCKER

Panzer Mk IV

The Panzer Mk IV tank was the common name for the German Panzerkampfwagen IV, the most widely produced and deployed German tank of the Second World War. First built in 1937, this medium tank had a crew of five, weighed 18.4 tons, and could travel at speeds of up to 31 kilometres per hour (kph). It was armed with a 75 millimetre main armament and two 7.92 millimetre machine guns.

Constant improvements to the design and protection resulted in later variants weighing up to 25 tons but still being able to achieve speeds of up to 40 kph. The armaments stayed the same, but improvements to the main cannon made the Mk IV very lethal. It was originally designed as a tank to provide direct support to the infantry and not to engage other tanks. However, due to the inadequacies of the German tanks designed for that role, the Mk IV soon took on the tank fighting role. The Mk IV chassis was used as the basis for numerous other armoured fighting vehicles, such as tank destroyers and self-propelled anti-aircraft guns.

The Mk IV was extremely reliable and robust. It saw action in all combat theatres of the war from North Africa to Italy to Occupied Europe, Germany, and the Eastern Front. In excess of 8,500 Mk IVs were manufactured from 1937–45, and it has the distinction of being the only German tank to remain in continuous production throughout the war. In total, the Mk IV represented 30 percent of the German Army’s total tank strength

Captain Hanson, in charge of the small rescue force, remembers his briefing from Brigadier Hill very clearly. The Brigadier pulled the young captain aside and explained in a cheery tone, “Hanson, old man, the Scots on our left are having some heavy going and we will have to go in to help them out.” Seconds later, they were racing to the fight.

The struggle for the Bréville area had developed into the most intense German offensive in 6th Airborne Division’s area since the D-Day drop. The Canadians arrived amidst a raging battle. The terrain was cluttered with smouldering vehicles and exploding ammunition. Bodies were strewn everywhere. The small band of paratroopers immediately deployed in the woods east of the Château de St-Côme. Tree branches snapped off and crashed around them as bullets and shrapnel cut a swath through the foliage. The Canadian paratroopers quickly dug in at the edge of the treeline, occupying some of the hastily abandoned positions of the Highland battalion.

Rummaging through the abandoned positions, the Canadians found three Vickers medium machine guns and plenty of ammunition. They quickly put their newfound firepower to use. The chatter of the Vickers quickly reached a crescendo as the paratroopers hammered the German attackers. “Three Sherman tanks pulled up on our right and stopped in front of our positions,” recalled Private Jan de Vries. “Suddenly, they were brewed up by German self-propelled guns.” As demoralizing as that was, what was worse was that the smoking hulks blocked their field of fire.

The Panzer Mk IV was the most widely produced and deployed German tank of the Second World War.

Many of the paratroopers were forced to move out to find alternate positions under heavy enemy fire. Throughout, Brigadier Hill hobbled from one position to another, encouraging his young paratroopers. His calmness in the utter chaos around him was inspirational to the Canadians. As the Brigadier approached a trench occupied by Private Michael Ball and his sergeant, an enemy shell exploded over their position. “My sergeant got killed,” remembered Ball. “He got a piece of shrapnel in the head, but Brigadier Hill, never backed down at all.” Hill’s amazing physical courage and love of his soldiers earned him the undying loyalty of his paratroopers.

DID YOU KNOW?

Media Darlings

Canada’s new paratroops were darlings of the media. The public image of the paratrooper became such that most people, both civilian and military, believed that airborne soldiers had nerves of steel and that they were virtual supermen. One Canadian reporter wrote:

Picture men with muscles of iron dropping in parachutes, hanging precariously from slender ropes, braced for any kind of action, bullets whistling about them from below and above. They congregate or scatter. Some are shot. But the others go on with the job. Perhaps they’re to dynamite an objective. Perhaps they’re to infiltrate through enemy lines and bring about the disorder necessary to break up the foe’s defence, where-upon their comrades out in front can break through. Or perhaps they’re to do reconnoitering and get back the best way they can. But whatever they’re sent out to do, they’ll do it, these toughest men who ever wore khaki.

Other newspaper accounts described them as “action-hungry” and as “the sharp, hardened tip of the Canadian Army’s dagger pointed at the heart of Berlin.” One journalist went so far as to write that the Canadian paratroopers were, “Canada’s most daring and rugged soldiers … daring because they’ll be training as paratroops: rugged because paratroops do the toughest jobs in hornet nests behind enemy lines.”

Another simply explained that “your Canadian paratrooper is an utterly fearless, level thinking, calculating killer possessive of all the qualities of a delayed-action time bomb.”

Even the Canadian Army acknowledged that “Canada’s paratroop units are attracting to their ranks the finest of the Dominion’s fighting men … these recruits are making the paratroops a ‘corps elite.’” The image of the new paratrooper was played up in newspapers who described paratroopers as virtual supermen.

The battle raged on for hours. At one point, Hill called in naval and artillery fire, which finally silenced the enemy’s tanks and self-propelled guns. Hill ordered the Canadians to clear the woods of enemy men. Savage hand-to-hand fighting was what it took to finally push the Germans back.

The Canadians fought aggressively, stood their ground, and forced larger groups of German infantry to fall back. The tenacious leadership of Hill and Hanson, coupled with the arrival of the paratroopers, lifted the spirits of the other British defenders and succeeded in blunting the German advance. “The Black Watch Battalion was completely disorganized,” wrote Hanson, “and I can safely say that ‘C’ Company saved a complete rout and a split in our left flank.”

The arrival of the Canadian paratroopers actually turned the tide of the battle. The ragged defenders, who had been shelled and battered by relentless German attacks for days and were on the verge of withdrawing, took heart and fought on. In fact, it was the German will that was broken. By 2200 hours that night, the Allies went on the offensive and by first light on 13 June 1944, they recaptured Bréville.

The Canadian paratroopers did not participate in the final assault to recapture the town. Having accomplished their mission of stopping the German breakthrough, they returned to their own position an hour before the Allied attack began; however, only 20 of the Canadian paratroopers made it back to their own lines. Over half of the original group was either wounded or killed in the heavy fighting at Bréville.

The Canadian paratroopers’ first week in Normandy had been gruelling to say the least. After being decimated by the bad drop, each day more paratroopers were lost to German attacks, shelling, and sniping. With each loss came additional responsibilities for those who survived, adding to their fatigue and the risk. There was no denying that combat in the close confined boscage country was intense.

The M4 Sherman tank was the armoured workhorse of the Allies during the Second World War.

FROM THE WEAPON LOCKER

Sherman Tank

The M4 Sherman Medium Tank was the primary tank used by the United States Army during the Second World War. It was also widely distributed to Allies. In total, over 50,000 M4 Shermans were produced and its chassis also served as the basis for thousands of other armoured vehicles, such as tank destroyers, self-propelled artillery, and tank recovery vehicles. The prototype model of the M4 was completed on 2 September 1941, and production began a month later. Most Sherman tanks ran on gasoline instead of diesel, which unjustifiably earned them the nickname “Ronsons” after the cigarette lighter, since once it was hit an M4 would explode and burn furiously. The British actually coined the slogan, “Lights up the first time, every time!” The cause of the easy combustion, however, was unprotected ammunition storage within the hull, not the gasoline engines or fuel tanks.

The early model Shermans had two .30 calibre general purpose machine guns and mounted a 75 millimetre medium velocity general purpose gun, which was replaced in January 1944 with a 76 millimetre gun. The British variants, called the “Firefly” mounted a 17-pounder (76.2 millimetre) gun, which had significantly better penetration power than the American ordnance. In February 1944, the Americans began producing M4s with a 105m Howitzer. The 32 ton Sherman tank normally had a crew of five. Its armour was effective against most German tank guns in the opening years of the war. Its frontal armour was 76 millimetre thick for the gun mantlet, 64 millimetre for the turret front, and 51 millimetre for the front of the hull. However, by 1943 its armour was inadequate against the German 75 millimetre, and later 88 millimetre, gun systems, as well as the German infantry anti-tank weapons such as the Panzerschreck bazooka and the Panzerfaust disposable one-shot rocket launcher. Nonetheless, steps were taken to increase its armour and in 1943 a modernization program for older tanks consisted of welding appliqué armour to the sides of the turret and hull.Throughout the war, progressively thicker armour was added in production to the front hull and front turret mantle in various upgraded models. In addition, field expedient methods, such as placing sandbags, spare track links, concrete, wire mesh, and even wood for increased protection, against shaped charge munitions was also practiced. Nonetheless, the Sherman still proved to be inferior to the German Panther and Tiger tanks that were introduced late in the war. However, the Sherman tank was mechanically reliable, easy to manufacture and service, and comparatively fast and maneuverable.

Adding to the difficulty were the warmer than usual weather conditions for that time of year in Normandy. One veteran recalled, “There was a pungent odour that constantly hovered over both sides of this clustered area like a black ominous cloud of death.” There was just no escaping the constant smell of decomposing flesh. It hung in the air — a constant reminder that death lurked nearby. This further tested the endurance of the airborne soldiers.

In the end the Battalion, despite the enemy’s best efforts, held their position. Lieutenant-Colonel Bradbrooke was justifiably proud of his unit’s performance:

The country around Le Mesnil was very close with its ditches and hedges, and it was a perfect position for determined boys like ours. We were just one little pocket out on the end of nowhere. After three days we had 300 men and we held for days against many attacks. The Germans were methodical as the devil but our mortars and machine guns knocked the hell out of them. Between 200 and 300 hundred dead Germans piled up in the fields in front of us and for days we could not even get out to bury them because of incessant sniping.

Brigadier Hill later referred to Le Mesnil as “one of the great battles of the war.” He noted, “In the first eight days I lost in 3rd Parachute Brigade over a thousand chaps and I think 58 officers. It was very, very tough.”

Finally, on 17 June, the remaining 312 exhausted paratroopers of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion were relieved by the 5th Parachute Battalion and sent to a rest area for a brief break to relax and refit. Until that point in the Normandy Campaign, the Battalion had suffered approximately 52 killed, 97 wounded, and 86 captured (all following the poorly dispersed drop). Although the rest was badly needed and greatly appreciated, it was to be short-lived.

FROM THE WEAPON LOCKER

Self-Propelled Gun

A self-propelled gun is a gun such as an artillery piece, anti-tank gun, or anti-aircraft gun, that’s mounted on a motorized wheeled or tracked chassis. In essence, a self-propelled gun can manoeuvre under its own propulsion compared to a towed gun that relies on a vehicle or other means to move it around the battlefield.

Self propelled guns should not be confused with tanks. Normally, self-propelled guns are more lightly armoured and often lack turrets. Conversely, tanks are typically heavily armoured with turrets. In addition, tanks are typically armed with guns designed specifically for destroying other tanks while only some types of self-propelled guns are designed for anti-tank warfare.

The tactical advantage of having self propelled guns, whether artillery, anti-tank, or anti-aircraft, lies in their mobility and flexibility on the battlefield. They allow for “shoot and skoot” tactics. Their light armour also provides increased protection for the gun crews. However, the cost of self propelled guns, compared to towed systems, often makes them very expensive and allows for fewer systems to be fielded.