The dark, turbulent sky leaked a tiny bit of light from the moon that peeked out between the rapidly moving clouds. Flight Lieutenant Lucian Robichaud stared out of his cockpit window as the constant droning of the C-47 Dakota engines lulled him into reflection. The day had finally arrived; the invasion of Occupied Europe was a go! Robichaud and his crew had trained for this moment for over a year, and now he was part of the greatest invasion in history — D-Day.

He was jolted from his thoughts by the sudden drop of the aircraft as it hit an air pocket. His co-pilot, Flying Officer Jim Kellogg, chuckled. “I wonder how the poor paratroopers in the back are doing,” he said.

“They’re supposed to be tough,” retorted Robichaud. “They’ll live — it could be worse.” And, he thought to himself, it probably will be.

The short flight across the English Channel was bad. First, it was a windy night. Second, because the armada of aircraft flew in formation, the turbulence of the preceding aircraft caused those in the wake to pitch and roll like corks on the ocean.

The fuselage of the plane was packed with paratroopers of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, a unit filled with the best of Canada’s fighting youth. Created in July 1942, exclusively from volunteers who were required to pass a rigorous selection process, the unit was attached to the 3rd Parachute Brigade of the British 6th Airborne Division during the summer of 1943. Like the crew of the Dakota aircraft, they had been preparing for this historic moment for a long time. Robichaud recalled the faces of the young men as they boarded the aircraft. There was a mixture of apprehension, excitement, and fear. But there was one thing that radiated from all of the troops: a fierce determination. A flow of pride swelled in him when he thought of the boys in the back of the airplane. He was momentarily struck by the irony of his thoughts. Although he was only in his late 20s, he could not help but think of those soldiers, many only 18 to 20 years old, as boys. Their boyhood would be over soon enough. He wondered how many would survive the impending combat.

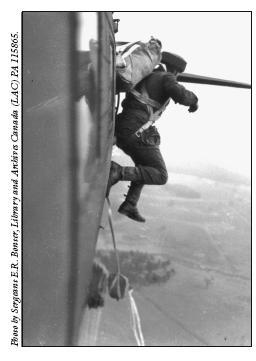

A Canadian paratrooper exiting a Douglas C-47 Dakota during a training jump in England.

FROM THE WEAPON LOCKER

C-47 Dakota Aircraft

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain, or Dakota, was a military transport aircraft that was developed from the Douglas DC-3 commercial airliner. It was a workhorse for the Allies in the Second World War to transport troops and cargo. Over 10,000 aircraft were produced during the war. In the European theatre of operations the C-47 and a specialized paratroop variant, the C-53 Skytrooper, were used in large numbers, particularly during the later stages of the war, to drop airborne troops and tow gliders. It was the C-47s in Canadian, British, and Commonwealth service that took the name Dakota, from the acronym “DACoTA” for Douglas Aircraft Company Transport Aircraft. The aircraft was so reliable that the United States Strategic Air Command continued to use the C-47 after the war, up until 1967. The Royal Canadian Air Forces also adopted the C-47 and used it throughout the 1940s and 1950s. After the Second World War thousands of surplus C-47s were converted to civil airline use. Some C-47s remain in use as late as 2010.

As the aircraft dipped and bucked in the night sky, the airborne soldiers suffered in silence. With their parachutes, personal equipment, and duffel bags, they carried well over 100 pounds each. Crammed tight on the aircraft’s wooden benches, they could hardly move.

The flight engineer surveyed the group. He already began to loathe the cleanup required once they dropped this group. It would start with one paratrooper and then quickly accelerate like a chain reaction. This occasion would not be any different. It was unavoidable. The question was not if it would start, but when. It was only a matter of time. Once the bucking, lurching aircraft claimed its first airsickness victim, the combination of turbulence, retching noises, and the smell would be too much for the others and, inevitably, more would succumb. Hopefully most would be able to find and use their air sickness bags in time.

“Skipper,” shouted Flight Lieutenant Bill Young, the navigator, over the noise of the aircraft, “we’re nearing the coast.”

DID YOU KNOW?

The Normandy Invasion

The Invasion of Normandy, commonly referred to as D-Day, was the Allied landing of military forces in Normandy, France, on 6 June 1944, which established an Allied foothold in Occupied Europe. The Allied leaders had agreed to the invasion at the Quebec Conference in August 1943. The Operation, code-named Overlord, was commanded by General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The ground force commander was Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery. The assault was the largest combined operation in history. The actual invasion began on the night of 5/6 June 1944, with airborne drops and glider landings, as well as massive bombing by aircraft and naval bombardments. Amphibious landings took place on the morning of 6 June on five beaches codenamed Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword. The landings were successful and by 12 June 1944, the Allies had united the five bridgeheads in to one continuous front line that was 97 kilometres long and approximately 24 kilometres deep.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

D-Day Statistics

The Normandy Invasion was the largest combined operation in history. The statistics tell a story of their own:

• 6,000 tons of bombs were dropped in the final hours prior to the invasion by 2,500 bombers.

• 23,400 Allied paratroopers jumped or landed in gliders behind enemy lines prior to the landings.

• 7,016 Allied naval vessels were used in the invasion, including six battleships, two monitors, 22 cruisers, 93 destroyers, 71 corvettes, and thousands of landing craft.

• 247 minesweepers swept 10 approach channels to the Normandy beaches.

• 195,701 Allied naval personnel, including the merchant marine, supported the invasion.

• 132,000 Allied soldiers landed on Normandy beaches on D-Day.

• 155,000 troops landed by sea or by air by day’s end on D-Day.

• 6,000 vehicles, including tanks, landed on D-Day.

• 171 Air Force Squadrons, consisting of approximately 7,000 fighters and fighter bombers, participated in the invasion.

• 26,000 tons of stores and supplies were required per day to sustain the Allied armies in Normandy.

Robichaud steeled himself. So far the fighter escort had protected them from enemy aircraft. They had flown fairly low and used the chaff — aluminium strips dropped from the plane — to fool the German radar, but no doubt the anti-aircraft batteries would zero in on the armada quickly enough. He had rehearsed this in his mind over and over. “Don’t panic,” he had always told himself, “there is a planeload of men depending on you.”

But he could not help but question himself. Would he be ready? How would he react? They had trained endlessly and discussed all sorts of contingencies. He knew that he and his crew were fit, well trained, and prepared. That knowledge gave him great confidence. Yet, tucked away in the recesses of his mind, in a corner he avoided, lived the nagging self-doubt of the untested.

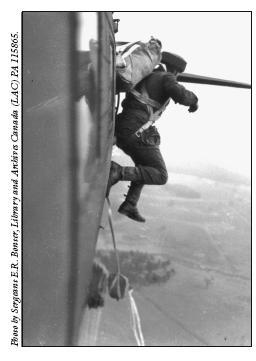

Mass drop during Exercise Cooperation in England, 7 February 1944. To prepare for D-Day, the exercise was designed to practise dropping the largest number of paratroopers in the smallest possible area, in the shortest amount of time.

FROM THE WEAPON LOCKER

Flak

The term flak refers to the bursting shells fired from anti-aircraft guns. The word originated in the Second World War and was derived from the German Flugabwehrkanone, which translates to, “aircraft defence cannon.” The acronym was broken down as Fl(ug)A(bwehr)K(anone). The term came in to general use to refer to any anti-aircraft fire that was aimed at airplanes from the ground during missions.

“Into the valley of death,” recited Kellogg in an attempt to show bravado. Suddenly the aircraft buckled as if it was hit by a thunderclap.

“Flak!” screamed Kellogg. “Take evasive action, Skip!”

Robichaud gripped the controls, sweat starting to form on his forehead despite the coolness in the cabin.

“No, we maintain a steady course at the jump altitude of 500 feet,” he replied in a calm, steady voice that surprised even him. He inherently knew that to control the fear of his crew he had to show a coolness that belied his own terror.

“Bill, how far to go?” queried Robichaud in the same steady tone.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

Airborne Missions on D-Day

Allied commanders understood that they had to ensure a smooth sea landing and breakout from five constrictive beaches within the first 24 hours of the invasion. They decided to use their airborne forces to protect the vulnerable flanks of the invading force. In the dead of night on 5/6 June 1944, three airborne divisions — two American and one British — were inserted behind German lines by parachute and glider. The American, British, and Canadian paratroopers occupied, defended, and guarded the eastern and western flanks of the invasion force during the initial days of the landing. The two American Airborne Divisions were assigned to protect the western flank. The first was the US 82nd “All Americans” Airborne Division, commanded by Major-General Matthew B. Ridgway and comprised of 6,000 paratroopers and 4,000 glider infantry. Ridgway’s mission consisted of capturing Sainte-Mère-Église, which represented a vital communication and transportation hub, as well as all causeway exits from Utah Beach. They also captured and defended the roads through the flooded area within their boundaries, including the bridges spanning the Douvre and Merderet Rivers. Once those objectives were secured, the 82nd Airborne Division set up defensive positions and repelled German counterattacks.

The second American Airborne Division was the US 101st “Screaming Eagles,” led by Major-General Maxwell Taylor. The 101st fought on the flank of the 82nd Airborne Division. Taylor’s 6,600 men were responsible for the capture and control of the causeways, bridges spanning the Douvre and Mederet Rivers, and all major roadways leading to Utah Beach within their designated area of responsibility. They also secured the designated Landing Zones (LZ) for the glider troops who landed later in the day.

The protection of the eastern flank was the responsibility of Major-General R.N. Gale, Commander of the British 6th Airborne Division (6 AB Div). His division was composed of the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades and the 6th Air Landing Brigade. Also attached to the Division was Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade.

The 6th Airborne Division secured and held a bridgehead on the high ground between the Caen Canal, the Orne River, and the Dives River. The control of this important elevated feature enabled units of the British 1st Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General John Crocker, to land and quickly move out from Sword Beach so that they could seize and consolidate a bridgehead south of the Orne River. Each of the Brigades had specific tasks and areas of operation. The 3rd Parachute Brigade, which included the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, captured the Merville Battery and destroyed its guns. In addition, they destroyed the bridges over the Dives and Divette Rivers to prevent German reinforcements and counterattacks from reaching the invasion beaches. Lastly, they held and defended a series of key roads to prevent enemy interference with the beach landings.

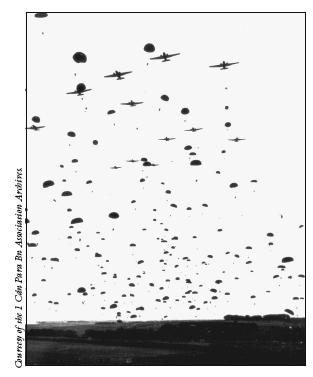

The glider fields of Normandy.

The 5th Parachute Brigade, under the command of Brigadier J.H.N. Poett, seized two bridges spanning the Orne, Ranville, and Bénouville canals by “coup de main,” using glider borne troops. Poett’s troops also cleared landing zones of obstructions and defended them for subsequent glider landings. The Brigade was charged with occupying and defending the Bénouville-Ranville-Bas sector.

The third brigade, the 6th Air Landing Brigade, was commanded by Brigadier H. Kindersley. Its three battalions and other specialized airborne units landed by glider later in the day on 6 June 1944 and held key terrain to assist in denying the Germans the ability to react effectively to the invasion.

Bill had been with Robichaud since their arrival in England in January 1943. He had respected his French Canadian superior from the beginning. He could sense in him a maturity and strength of character.

“Ten minutes, Skipper,” he shouted back with a smile, figuring he would do his part to maintain an air of confidence. He had long ago learned that courage, much like fear and panic, was infectious.

This was a classic case of something being easier said than done. Until that moment the flight had been admittedly rough. By now their journey had gone from a bumpy ride to a passage through hell. Peering out of the cockpit, Kellogg could see the exploding greyish-black puffs of smoke made by the anti-aircraft (AA) shells exploding in the sky. Some of their companion aircraft had already been hit. Nearby a crippled Dakota, smoke pluming from the left wing, wobbled dangerously as the pilot attempted to bank away from the action. If they could control the fire they might even make it home again. Others had not been so lucky, victims of AA fire that had obviously found the proper range. Although he was terrified, Kellogg managed to find a grotesque beauty in the way some of the flaming and pirouetting aircraft spiralled to the ground.

DID YOU KNOW?

D-Day

The term D-Day was the Second World War term for the day designated that an invasion was to go ashore. The letter “D” was the military symbol representing the day the operation was to happen. H-hour stood for the designated hour that the operation was to begin.

Anger welled in Robichaud as he watched the planes in his formation attempting evasive action. Some quickly climbed for additional altitude to get out of range of the deadly AA fire, while others peeled away from the formation to distance themselves from the obvious focus of the enemy gunners. This behaviour was contrary to their direct orders, would certainly compromise mission success, and could potentially doom their cargo — the paratroopers who depended on them for an accurate, safe drop.

Robichaud’s anger was short-lived. The aircraft suddenly pitched and rolled in a way he had never before experienced. It felt as though a giant had cast an invisible net that grabbed the aircraft in mid-flight and stopped it dead. The effect was instantaneous, as if his controls were being wrenched from his hands.

His graceful workhorse had become a lumbering, mortally wounded mule.

“Skip, starboard engine is on fire and the whole wing is in flames,” shouted Kellogg.

“Sir,” yelled the no-nonsense flight engineer who suddenly appeared on the flight deck, “we’re hit hard — it doesn’t look good.”

“Thanks Sarge,” replied Robichaud in an even tone, without looking back. He knew his aircraft was doomed. He could feel its lifeblood slipping through his hands at the controls. His attention was now focused on saving his crew and their cargo.

“Prepare to evacuate,” he ordered almost in a hushed tone.

“Bill, let me know when we’re safely over land,” he asserted.

“You got ’er Skip,” came the immediate reply.

Robichaud now tried to coax every last ounce of strength from the stricken aircraft as he clawed for extra altitude to give the paratroopers and his crew a fighting chance to jump. Bill Young, the navigator, patted Robichaud’s shoulder.

“Skip, we’re good,” he calmly stated with a sense of finality.

“Hit the evacuation bell,” Robichaud directed, and smiled at his faithful companion. They had weathered countless flights. He knew with an inescapable certainty that this would be their last run together.

The paratroopers in the fuselage reacted the moment the alarm bell sounded. Their training had conditioned them for an immediate response to the bell. Despite their fear of the overwhelming and obvious crisis facing them, all quickly swung into action as they’d been trained to do by the drills they had practised over and over again. The result was that they felt like they had control over the situation. As an added incentive, all were more than happy to escape the doomed airplane.

The flames, fuelled by the wind, danced in the small starboard windows. Smoke was already billowing into the aircraft.

“Stand up!” shouted the Jumpmaster, swooping his hands up in the air in unison with his command.

“Hook up!” he yelled and tugged his hand down in mid-air as if it caught on an imaginary line.

“GO!”

Fuelled by adrenaline, despite their heavy awkward loads the paratroopers quickly waddled forward to the side door and threw themselves out of the port side exit, one by one.

Robichaud continued to struggle with the sluggish controls. The aircraft seemed to wheeze and shudder, as though it was gasping for its last breath of air, barely clinging to life. He could no longer climb and he was trying to hold the altitude he had.

His airspeed was dropping dramatically.

“Suit up and bail,” he yelled over his shoulder.

“No way, Skipper! We’ll ride it out with you,” replied Kellogg, with false confidence.

Robichaud smiled. “No you won’t Jim. Bail out, that’s an order — and take the rest with you.”

Kellogg looked at Bill Young, but he just motioned him on.

“We’ll be right behind you, Jim,” urged Young. “Now get the rest of the crew out. We can’t afford to waste any more time talking about this.”

Squinting his eyes against the heavy fumes, Jim worked his way back. He shook his head in frustration. He could barely see. Every breath was a struggle and the stench of burning nylon, oil, and metal was unbearable. He could hear the rush of wind through the jump doors but the fuselage was filled with a black smoke. He groped in the dark for his parachute, feeling along the contour of the aircraft’s interior. Clarity hit him like a bolt of lightening. His thoughts coalesced with an abruptness that, despite the crisis, made him stop momentarily and remember how their Skipper had spent so much time making them go through drills blindfolded back in England. They all just humoured him, thinking he was just a little over zealous. But now he realized those “stupid” drills were meant to prepare them for just such a crisis.

Shaking himself back to reality, he mentally thanked his superior for his foresight and quickly donned his parachute.

Just as Kellogg was buckling up, he felt someone grip his arm and heard the voice of the Sergeant Aaron Flint, the flight engineer, in his ear.

“We better go,” urged Flint. He coughed, canted his head sideways to spit, then added, “There’s not much time left.”

Kellogg patted him on the arm and nodded his acknowledgement. The two men made their way to the door and leapt from the dying aircraft.

In the cockpit, Robichaud fought to hold the airplane together. “Okay, Bill, your turn.”

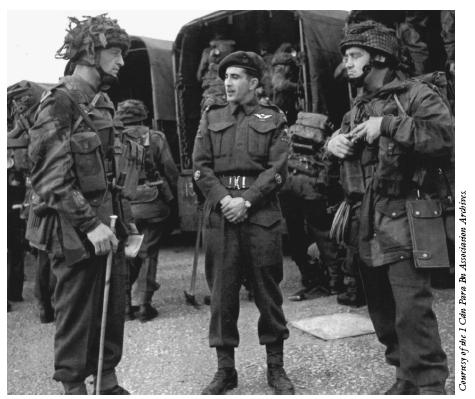

On 24 May 1944, the unit loaded onto trucks with only their webbing, ammunition, and weapons. They then drove 50 miles to their transit camp near the village of Down Ampney, where they loaded onto aircraft for their short flight to Normandy on the night of 5 June.

“No, Lucien, we’ll ride this one out together, just like we have all the other tough times,” replied Young, in a steady, calm voice.

Robichaud smiled. This was what he cherished the most of his service. He remembered when he told his family he had enlisted. At the time, he did not join because of a sense of duty to Canada or England. He sought adventure and an escape from the constricting life in Dégelis, Quebec. His announcement had torn his family apart, but he left nonetheless. As he trained as a pilot in Western Canada, he grew to appreciate his country even more than he would have thought possible. During his time in England, his pride in what it meant to be a Canadian continued to swell within him. He could not help but think back to a few punch-ups in London with a measure of fondness. Canadians could make fun of each other, but they drew the line when outsiders thought they could have a go too.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion (1Cdn Para Bn) was established by government order on 1 July 1942. It was Canada’s first airborne unit. Recruiting began immediately and volunteers from units across Canada were put through a rigorous selection process. In October 1942, those who passed were sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, for training because no Canadian facilities were available. That changed in March 1943, when the S-14 Canadian Parachute Training School at Camp Shilo, Manitoba, was completed. After that time all parachute candidates trained and qualified in Canada. Although the Battalion was established for home defence, Army commanders decided its real purpose was as an offensive weapon to strike deep behind enemy lines. Therefore, that same month, March 1943, although the Battalion had not yet completed all of its training, it was attached to the newly formed British 6th Airborne Division in the United Kingdom. The Battalion deployed to England in July 1943, and arrived at its new base in Bulford in early August. Once on the ground, they quickly underwent an intensive training regime as part of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, under the battle-tested Brigadier James S. Hill, to prepare for the invasion of Normandy.

In the end, his comrades were what really mattered — those with whom he had shared hardships and who had come to be like brothers to him and to each other. His crew and the other members of his squadron, they were the ones with whom he shared danger; the ones he laughed with, cried with, and shared his dreams with. He loved his country, but these friends were what he would risk his life for — not a country, nor political or ideological notions.

“Look Bill,” Robichaud turned and mustered as much confidence as he could. “Neither one of us is going to die today, but the longer you lounge around the less time I have to bail out. So you’d better haul ass or you’ll condemn us both to death.” Then, in a very calm tone, he almost pleaded, “Please go — I’ll be right behind you.”

Bill steadied himself and looked into the eyes of his friend. He simply nodded, unable to utter a sound. He gripped Robichaud’s shoulder, tears welling in his eyes, and then disappeared into the rear of the plane.

Time seemed to stand still. The aircraft was coughing, sputtering, and almost lurching in the air. Robichaud fought the controls with all his strength, trying to hold it steady for just a little longer to ensure that Bill could bail out. Then, the aircraft suddenly pitched to the starboard. The wing had finally disintegrated and the plane began its death spiral.

DID YOU KNOW?

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin considered the idea of airborne warfare as early as 1784. In Paris he witnessed the second flight of a Jacques Charles hydrogen balloon, made of silk and fuelled by a mix of hydrogen and hot air.

Upon seeing it in flight he wrote to a friend and asked, “Where is the Prince who can afford so to cover his country with troops for its defence, as that ten thousand men descending from the clouds might not, in many places, do an infinite deal of mischief before a force could be brought together to repel them?” Franklin went on to argue that 5,000 balloons, each capable of carrying two men, would not cost more than five ships. He insisted that the freedom of movement and mobility would give a huge advantage to those who dared to fight from the sky. Franklin believed that this “magnificent experiment appears to be a discovery of great importance, and what may possibly give a new turn to human events.”

His imaginative idea of using the sky to wage war would not be realized for more than a century.