Individual battles of courage and determination like the one described in the last chapter were being played out all over the coast of France that night. Under cover of darkness, in the late hours of 5/6 June 1944, the Allies unleashed their airborne army to begin the invasion of Occupied Europe. In a small airstrip in Down Ampney, England, 36 C-47 Dakota aircraft transporting the main group of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion and part of the headquarters staff of the 3rd Parachute Brigade had lifted off for their trip to Normandy, France. The aircraft closed up in tight formation and headed toward the French coast. The steady drone of the armada filled the fuselages and drowned out all other noise. The heavily laden Canadian paratroopers, crammed in the restrictive, dark confines of their airplanes, shifted uneasily as the planes dipped and rolled in the wake of the preceding aircraft.

The atmosphere was subdued. Some paratroopers slept or prayed, while others nervously studied their assignments. Corporal Harry Reid gazed out a window, observing the ghostly silhouettes of the other Dakotas. “Then it hit home,” recalled Reid. “We were finally on our way!”

To many, that flight seemed to take forever. However, in the distant horizon, the French coast was already within sight.

“Stand up,” bellowed the Jumpmaster. Despite this much anticipated order, the paratroopers clumsily struggled with their heavy loads and leg-kit bags to assume their position within each “stick” (or row/line) of jumpers. Each man strained to hook his static line to the overhead cable. The Dakotas jerked and rocked violently as the pilots tried to avoid a deadly flak barrage that filled the sky as they crossed the coastline. The heavy fire forced the aircraft to break off from their assigned flight trajectory. Many pilots, against orders, veered off their assigned flight paths and dropped to altitudes ranging from 400 to 700 feet, in an effort to escape the lethal hailstorm.

As the pilots desperately tried to get back on course, the navigators scrutinized the rapidly unfolding French terrain, hoping to recognize landmarks that confirmed the direction of their final approach to Drop Zone (DZ) “V.” Meanwhile, the paratroopers were violently thrown about within the aircraft. Static lines became tangled and equipment began to snag on the plane’s interior. Individuals cursed as they scrambled to stand up long enough to execute their pre-exiting drills as the jumpmasters barked out orders.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

6th Airborne Division.

The 6th Airborne Division was a British Army airborne division during the Second World War. On 23 April 1943, the British War Office ordered the formation of a second airborne division to supplement the original British 1st Airborne Division that was created in 1942. Command of the new airborne division was given to the newly promoted Major-General Richard Gale who had raised and trained the 1st Parachute Brigade and then gained combat experience with it in North Africa. The core of the new Division was centred on 3 Parachute Brigade and 1st Airlanding Brigade (renamed the 6th Airlanding Brigade), both reassigned from the 1st Airborne Division. In June 1943, the 5th Parachute Brigade was added to the Division. By September 1943, the 6th Airborne Division was almost at its full strength of approximately 8,500 men.

Each parachute battalion within the division consisted of about 650 men. The air-landing battalions were slightly larger, with about 750 men each.

The Division participated in the Normandy invasion and subsequent campaign. It also deployed forces in reaction to the surprise German Ardennes offensive in December 1944, and dropped in support of the crossing of the Rhine River in March 1945, and the final pursuit and destruction of the German Army. At the end of the war in Europe, the Division was earmarked to deploy to the Far East for operations against Japan. However, those plans were cancelled after the atom bombs were dropped on mainland Japan and the war came to an end. The Division was sent to Palestine, on internal security duties, where it remained until it was disbanded in April 1948.

The evasive actions of some of the pilots resulted in paratroopers not being able to get out of their aircraft. Nineteen-year-old paratrooper, Private Bill Lovatt, recalled, “As we approached the DZ the aircraft took violent evasive moves and as I approached the door I was flung back violently to the opposite side of the aircraft in a tangle of arms and legs.”

Major Dick Hilborn remembered, “As we crossed the coast of France the red light went on for preparing to drop. We were in the process of hooking up when the plane took violent evasive action … five of us ended up at the back of the plane.”

In some cases, paratroopers close to the door were flung out into the sea. Sergeant John Feduck was slightly more fortunate. “Before the light changed the plane suddenly lurched,” he reminisced. “I couldn’t hang on because there was nothing to hang on to so out I went — there was no getting back in.” Luckily, he was already over France and he landed on solid ground.

Throughout the turbulent ordeal, the Jumpmasters urgently tried to restore order, despite the hot, jagged shrapnel that ripped through the thin skin of the Dakota aircraft. Many of the occupants were surprised at how badly the aircraft bounced around in the air because of the German flak.

DID YOU KNOW?

Airborne Forces

Airborne forces are specifically organized, equipped, and trained for delivery by airdrop or air-landing into an area to seize objectives or conduct special operations. The three primary missions for airborne forces are: Seize and Hold Operations; Area Interdiction Operations to prevent or hinder enemy movement or manoeuvre in a specific area; and Airborne Raids.

Not surprisingly, this extraordinary night jump would forever be etched in the very souls of the young paratroopers. “When I left the aircraft it was pitching,” stated Company Sergeant-Major John Kemp. “I was standing in the door. There were 20 of us in the aircraft. I had 19 men behind me pushing. They wanted to get the hell out. The flak was hitting the wings.”

Private Anthony Skalicky’s plane was one of those actually hit. One of the engines burst into flames, spewing thick black smoke. The plane was losing altitude and even though they were nowhere near the drop zone, “the entire stick just ran out the door,” recalled the frightened paratrooper. “I couldn’t get out of the plane fast enough,” he recalled.

Meanwhile, many of the other airplanes tried to maintain formation as best they could. Inside the aircraft red lights came on, indicating that the drop zone was only minutes away. Fear was forgotten as the paratroopers desperately strained to steel themselves for the coming jump that would allow them to escape this airborne hell. Mercifully, the green light finally flashed on. “Go!” hollered the Jumpmaster as he literally pushed the first jumper out the door. He was followed by the remainder of the paratroopers who were not already wounded. The heavy loads the paratroopers carried hampered their exit cadence, causing the sticks of paratroopers to be dropped over a much longer distance.

DID YOU KNOW?

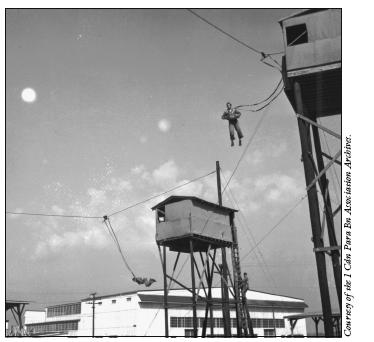

The Basic Parachute Training Course

The basic parachutist course was a physically and mentally demanding experience. All aspiring paratroopers who wanted to take the course were volunteers, and had to successfully pass a rigorous selection process. The four week course was divided into four distinct stages:

“A” Stage: Physical and endurance training, running, Jiu-jitsu, and hand-to-hand combat classes.

“B” Stage: Instruction on ground landing techniques, landing swings, oscillation drills, exiting drills from dummy fuselages and Mock Towers, and wind machine training.

“C” Stage: Instruction on the various components of a parachute and their function, parachute packing classes, High Tower shock harness, and controlled parachute descent training.

“D” Stage: Jump Stage. This was the climax of the course. Candidates put into practise everything they had learned. Each candidate had to successfully complete five daytime jumps to become parachute qualified. At any time during the training, a candidate could remove himself from the course. During “D” Stage, candidates who refused to jump were automatically failed and immediately returned to their units.

“With 60 pounds of equipment strapped to our legs, not to mention the other equipment we were wearing, we couldn’t run out the door,” explained Private William Talbot, a member of the anti-tank platoon. The paratroopers shuffled to the door and just dropped out.

Some pilots did not reduce their speed, further complicating the already stressful night jump. “The plane was going much too fast,” recollected Captain John Simpson of the Battalion’s signal platoon. “When I went out the prop blast tore all my equipment off. The guy must have been going at a hell of a speed. All I had was my clothes and my .45 revolver with some ammo.”

The majority of the paratroopers exited on the initial run. Others were not so lucky and had to relive the hellish experience, enduring a second pass over the DZ. “I was number 19 in the stick of 20 in my plane,” explained Corporal Ernie Jeans, a medic from Headquarters Company. “As I made my way to the door, I heard the engine rev up and the jumpmaster pushed me back.”

The 35 foot Mock Tower used to practise aircraft exits proved to be the most dreaded of training apparatus. Many found it more intimidating than exiting from a real aircraft.

“I thought to myself that we had come all this way to go back to England.” He needn’t have worried; the aircraft racetracked and headed back to the DZ to drop the two remaining paratroopers. A few days later, Jeans learned that the remainder of his stick had been dropped off course on the initial run and that all had either captured or killed.

As Private Jan de Vries exited the aircraft he was met by an abrupt rush of wind that physically yanked him into the slipstream of the aircraft. Suddenly, the noise and the pandemonium of just a few moments before disappeared. An eerie silence surrounded the paratroopers who drifted to earth, seemingly alone.

“Going down I was surprised at the quietness and the darkness,” Corporal Boyd Anderson recollected. “I had expected to hear sounds of shooting or at least some activity.” Engulfed in the inky darkness the paratroopers were given a moment of respite. However, that relief abruptly ended. The solitude and peacefulness of the parachute descent were soon replaced by the reality of combat.

Sometimes the exits from the aircraft were too fast. Corporal Tom O’Connell left the aircraft too quickly and his parachute got tangled up with another jumper’s. “As we plunged toward the earth I heard the other fellow yell from below, ‘Take it easy old man!’” Both men crashed to the earth. Around noon, a severely injured O’Connell had finally regained consciousness. Beside him was the corpse of Padre Captain George Harris. On the ground beside him he could see the two parachutes twisted together like a thick rope.

Tumultuous exits were not the only danger. Difficult landings were also a problem. The lucky ones hit solid ground, albeit rather heavily. “When I landed flat on my back,” reminisced one veteran, “I was in such agony that I cared very little whether I lived or died.” But, “then the training took over,” he explained. “I immediately pulled out my rifle and at the same time hit the release on my parachute. I placed my pack on my back and with the rifle in my arms I started to crawl toward a clump of trees which I could see very dimly. At this time I heard nothing, not an aircraft, not a bomb, not a shot.” Like many that night, he was lost and alone.

Several paratroopers crashed into trees or slammed onto buildings, resulting in serious injuries and deaths. Among the first casualties was the Battalion’s medical officer, Captain Colin Brebner, who had landed in a tree. Due to the darkness, Brebner misjudged his altitude. The anxious officer proceeded to cut his suspension lines and fell 40 feet to the ground. He broke his wrist and pelvis.

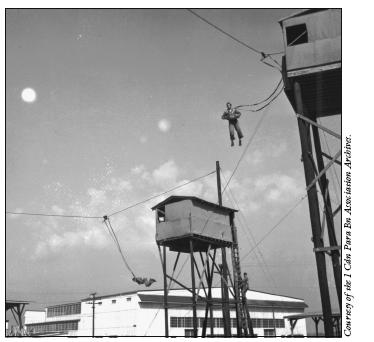

O’Connell and Brebner were not alone in their misery. Many paratroopers sustained injuries on landing. But those landings paled in comparison with landing in the dreaded flooded and marshy areas. “Looking out of the plane it looked like pasture below us, but when I jumped I landed in water,” recalled Private Doug Morrison. “The Germans,” he explained, “had flooded the area a while back and there was a green algae on the water so it actually looked like pasture at night from the air.”

Because they were heavily laden with equipment and ammunition, many Canadian paratroopers drowned. Sergeant W.R. Kelly was one of the lucky paratroopers who cheated this watery grave. One man found Sergeant Kelly hanging upside down from a huge tree with his head in the water. Kelly’s parachute suspension lines were knotted around his legs and feet. The canopy had caught on a limb and suspended Kelly so he was submerged from the top of his head to his neck. The eighty pounds of equipment that he carried was now bundled up around his chest. To keep from drowning, Kelly was required to keep lifting his face above the water for mouthfuls of air. He was nearly exhausted when a fellow Canadian found him, cut him loose, and helped him to dry land. Others were not so fortunate. Many drown in the flooded fields.

FROM THE WEAPON LOCKER

The Paratrooper as a Weapon System

Major-General Richard Gale, the commander of 6th Airborne Division, described the paratrooper as a weapon system. He wrote, “He [paratrooper] is aware, too that once on the ground his future lies in his own skill. The gun which he carried down in his drop and the small supply of ammunition on his person are his only weapons for support in either attack or defence. His water and food are what he can carry when he jumps. His sense of direction, his field-craft in map reading and his physical strength must all be of a high order. He may be alone for hours, he may be injured, he may be dazed from his fall. But it is his battle and he knows it.”

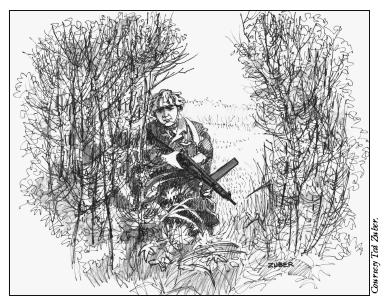

Wet Landing in a Norman field by Canadian war artist Ted Zuber.

The problems for the Canadian paratroopers had just begun. The parachute drop had been a disaster. The drops were widely dispersed and scattered. The evasive action of the pilots had created some of the problems. Lingering smoke and dust created by heavy, ongoing bombing also made navigation difficult. The situation was exacerbated by the failure of the Eureka homing beacons to function properly. As a result, during the hours following the airborne insertion those who had been dropped off course experienced difficulties in identifying their location. Additionally, the dark night and the fields partitioned by high hedgerows further impeded the ability of the paratroopers to confirm their positions.

“Airplanes dropped us all over hell’s half acre,” complained Lance-Corporal H.R. Holloway.

“On landing,” commented Private de Vries, “I wondered where I was and where the others were. I got out of my chute and quietly moved to the hedgerow at the edge of the field. I was lost. I could not recognize anything.”

Corporal Dan Hartigan acknowledged, “The scattering had an operating influence on the whole battle. We lost more than 50 percent of our officers on D-Day, 15 of 27.”

Some paratroopers were lucky and would eventually rejoin their units, having been briefed on how to orient themselves after their landings. Others were not. “I tried to find out where I was, but could not,” Sergeant Feduck recalled. “I wandered for an hour or so with no success. I laid down in a bomb crater and tried to get my bearings. Finally, I spotted two English chaps, we moved out to find our respective units.”

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

Rebecca/Eureka Beacons

The Rebecca/Eureka transponding radar was a transponder system used as a radio-homing beacon. It formed a system of portable ground-based beacons and airborne direction finding equipment that was initially designed to assist the air-drop delivery of supplies to Resistance groups in Occupied Europe. The Rebecca interrogator unit, which was located in an aircraft, transmitted hundreds of pulses per second on a given frequency. Upon receiving this signal, the mobile, ground based Eureka emitter rebroadcast the pulses on a different frequency. This rebroadcast signal was received by two special directional aerials on the aircraft carrying the Rebecca unit. This enabled the pilot to confirm his approach and distance to the DZ. The difference in signal amplitude between the two aerials gave the bearing of the Eureka beacon, while the delay between transmission and reception of the return pulses gave the range. The system was only effective to within approximately three kilometres. The Rebecca code name was derived from the phrase “recognition of beacons.”

Although normally successful for dropping equipment in support of resistance movements throughout the war, the Rebecca/Eureka system did not have the same level of success on larger allied airborne operations. This was mainly due to poor operational planning and damage to ground equipment during the drop of the pathfinders who were responsible for setting up the ground emitters.

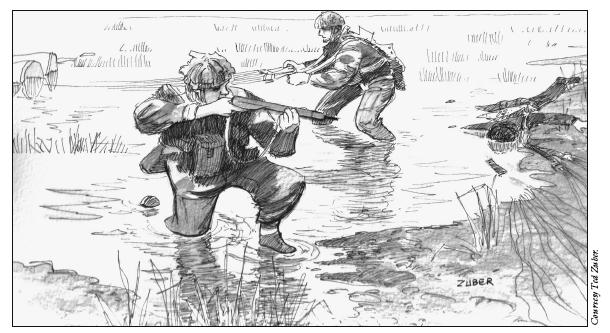

A Canadian paratrooper talks with a member of the French Resistance during the initial days of the campaign.

“If you are in doubt of the location of the RV,” stated Lance-Corporal D.S. Parlee, “we were instructed to face the line of incoming aircraft and then move off to the left of their flight path. That was all well and good until I discovered that every aircraft I could see was going in a different direction.” Sergeant Denis Flynn felt that the dispersal “changed the whole attitude — once on the ground we all wondered, ‘where are we?’ Because of the dispersal of the drop I was separated from my group. Things were a little strange … I wondered, ‘where am I? How do I meet up with the others’? … There were a lot of anxious moments.”

However, as dawn pierced the heavy smoke and clouds, the increasing daylight helped numerous paratroopers find their way to their objectives. But to some of the paratroopers, who found themselves in the midst of German positions and troops, the early morning sunlight quickly proved to be a dangerous hindrance.

The net result of the aerial difficulties began to manifest on the ground. Many of the paratroopers who were not drowned or killed on landing were hopelessly lost. In fact, 82 paratroopers became prisoners of war. Some, like Private Anthony Skalicky, were captured shortly after their landing. “Another paratrooper and I decided to move out,” recollected the unlucky paratrooper. “We walked on a road and were suddenly surrounded by German bicycle troops. We were searched, tied up, and marched off.”

Others were more fortunate and successfully eluded enemy patrols. “I came face to face with a German patrol,” explained Private Morris Zakaluk of the heavy machine gun section. “I counted six men in single file about three paces apart. They were in full battle gear, rifles, submachine guns, grenades, one man packing a radio.” Zakaluk took a bead on the lead man, but held his fire. They turned left and proceeded along a hedgerow, disappearing into an opening. A minute or so later another three enemy soldiers appeared with an MG 42 machine gun. Zakaluk was lucky he had held his fire. The machine gun crew certainly would have made short work of him. “I surely would have been a dead duck,” concluded Zakaluk.

In the end, only one third of the Canadian paratroop force was actually able to assemble at their designated rendezvous points and carry on with their missions. Although this wide dispersal greatly complicated their initial missions, it also had the unexpected benefit of confusing the German defenders. Unable to confirm the exact area of the drop zones, German commanders delayed deploying their reserve forces for many hours. This gave the paratroopers an opportunity to get somewhat organized.

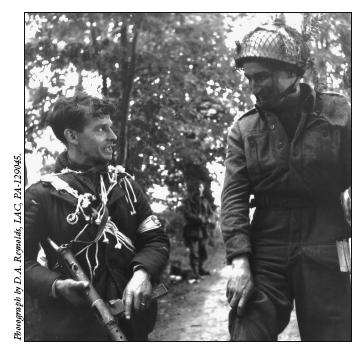

A Canadian paratrooper carefully checking for enemy through a gap in the heavy foliage.

Landing in the town of Varaville, the Deputy Commanding Officer, Major Jeff Nicklin, witnessed this confusion first-hand. “The Germans were really windy in Varaville,” he observed. “They ran around that town like crazy men and shot at anything that moved. Even a moving cow would get a blast of machine-gun fire. They were so jumpy [that] they ran around in twos and threes to give themselves moral support.”

The dispersal of Battalion Headquarters personnel severely limited the command and control capabilities of the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel G.F.P. Bradbrooke. He had difficulty organizing his battalion, as well as communicating with his Brigade and Divisional headquarters during the first 24 hours. “I personally was dropped a couple of miles away from the drop zone,” recounted the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion commanding officer (CO), “in a marsh near the River Dives and I arrived at the rendezvous about one and a half hours late and completely soaked.” Bradbrooke recalled the immense difficulty of trying to get some sort of order out of all the confusion and chaos.

On the bright side, the CO asserted that his stick was not troubled by the enemy during and immediately after the drop because he figured the enemy was just as confused as they were. In the end, Bradbrooke insisted that although the fighting was hard enough at times, the most difficult task was getting everyone organized after they hit the DZ.

DID YOU KNOW?

“Jump Wings”

Badges and insignia have always held a very special place in a soldier’s heart. Nothing embodies that more than the Parachutist Qualification Badge, more commonly referred to as “Jump Wings.” Upon successful completion of a formal Basic Parachutist Qualification Course, a paratrooper would receive his “Jump Wings” on graduation. The Canadian Parachute Badge was a cloth, machine embroidered badge. A white deployed canopy was centred between two horizontal wings. The shroud lines were placed behind a gold coloured maple leaf. The badge was stitched onto a dark green backing and sewn over the left breast pocket of the Battle Dress and Service Dress tunics. Later, it was also worn on the paratroopers’ Denison Jump Smocks. To ensure that only those qualified could wear the badge, in early January 1943 all qualified parachutists were issued with a Canadian Parachute Badge card that had to be carried by qualified personnel at all times. The card had to be shown upon request to confirm that the individual was, in fact, a qualified paratrooper. Non-qualified personnel caught wearing the badge faced disciplinary action.

Lieutenant-Colonel G.F.P. Bradbrooke, Commanding Officer of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, on D-Day.

But the widely scattered paratroopers were not their only problem. Because many of the aircraft failed to slow down to allow the paratroopers to jump out safely, most of their heavy equipment was lost. As the paratroopers had exited the fast moving aircraft, their equipment was ripped away by the heavy wash of the airplane slipstream. In addition, some equipment was lost when the leg-kit bags were released by the paratroopers. The shock of the heavy kit bags coming to a sudden stop at the end of the full extension of the 20-foot rope caused the bottom of the canvas bags to rip open. Paratroopers watched helplessly as their heavy weapons, equipment, and much needed extra ammunition and explosives fell, scattered, and disappeared into the darkness below. A frustrated Major Hilborn, who commanded the heavy machine gun platoon, reported that he had only two Vickers machine guns, one tripod, and a limited amount of ammunition. Corporal Ernie Jeans, one of the few surviving medics, was also very concerned. The battle had not even started and he found himself with hardly had any medical equipment or supplies. More than 70 percent of the Battalion’s heavy equipment, support weaponry, and supplies were lost before a single shot had been fired.