Despite the chaos, the paratroopers began to assemble to carry out their missions. Those who had landed away from the drop zone adapted to whatever unplanned situation unfolded. “I began to meet up with others and we made our way toward our objective,” said Sergeant Denis Flynn, “Everyone knew what was required and we did whatever could be done under the circumstances.”

Brigadier James Hill, their respected and beloved Brigade Commander, had warned them that “One must not be daunted if chaos reigned [because] it undoubtedly will!”

The Brigadier’s words provided some degree of reassurance to the paratroopers. “I think most of us anticipated that we could go into battle by dropping right onto our objective — right into battle,” confessed Private de Vries. He clarified, “Nonetheless, Brigadier Hill warned us that chaos would reign.” And it did!

Now the paratroopers, as individuals and small groups, began to fulfill their tasks. “C” Company was part of the 3rd Parachute Brigade’s advance party and landed before the main group. They exited their Albemarle aircraft between 0020 hours and 0029 hours, 6 June 1944, and were some of the first Allied soldiers to invade Occupied Europe. While most of the men of the first aircraft landed on or near DZ “V,” northwest of Varaville, those in the subsequent aircraft were dropped between eight and 10 kilometres from the intended point.

Shortly after landing on their designated drop zone, the Canadians, as well as the members of the 3rd Parachute Brigade pathfinder teams, experienced serious difficulties. As mentioned, many of their Eureka beacons, required to guide the main body to the DZ, had been either damaged or lost. This equipment failure proved disastrous. Less than 50 paratroopers reached their rendezvous (RV) assembly point. Regardless, an impatient Company Commander, Major H.M. McLeod, refused to wait. With the impending arrival of the main body of 3rd Parachute Brigade, including the remainder of 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, it was important that “C” Company accomplish its initial task of securing the DZ.

Once the area was secured, McLeod split up his skeletal force and dispatched one group to seize and hold the Varaville Bridge. These paratroopers were instructed to defend the structure at all costs until the arrival of the airborne engineers who were tasked with destroying it. Then, McLeod and the remaining men proceeded to their next objective — the capture of a series of defensive positions located on the grounds of Le Grand Château in Varaville. McLeod wanted to use speed and the cover of darkness to assist in the attack. He knew that these two factors combined with bold aggressive action and surprise would offset his temporary lack of manpower. Upon arrival in Varaville they located, captured, and disabled a German communication centre. McLeod then organized his men into small groups to seize the remaining positions, which consisted of a bunker, a series of trenches, and an anti-tank gun position. However, as the paratroopers deployed and inched their way toward those positions, the defenders opened up with a barrage of small arms and machine-gun fire. The darkness was illuminated by bright orange explosions and tracer ammunition that arced through the night sky.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

Canadian Parachute Battalion D-Day Missions

Brigadier James Hill tasked the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion with a number of vital D-Day missions. First, the Battalion was responsible for securing and protecting 3 Parachute Brigade’s DZ “V,” as well as neutralizing an enemy headquarters, a communications centre, and defensive positions located in the DZ’s immediate vicinity. In addition, the Battalion was tasked with supporting the airborne Royal Engineers (RE) in the demolition of bridges at Varaville and Robehomme. And they were to deny the enemy the use of all roads in the Battalion’s sector. Upon completion of these tasks, the rifle companies were to regroup and defend the area in the Le Mesnil, Varaville, Bois de Bavent, and Bréville area.

During the first hours of the invasion each company within 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was to operate independently from one another. “C” Company was detached from the Battalion and flown in as part the 3rd Parachute Brigade’s advance party so that they could be inserted ahead of the Brigade to secure DZ “V,” located between the Merville Battery and the Varaville Bridge. Once secured, the Brigade’s pathfinders set up signal beacons to guide the aircraft of the main group to the DZ. Once that was done, “C” Company was responsible for the destruction of communication headquarters and defensive positions in Varaville. The Company also provided support for the airborne engineers who were assigned the mission of destroying the bridge at Varaville. Following the demolition of the structure, the paratroopers defended the road through that town in order to deny the Germans access to the beaches. They were relieved by elements of the 1 Special Service Brigade Company later in the day and then deployed to the Le Mesnil crossroads to assist with its defence.

“A” Company jumped with the main group. Its mission consisted of protecting the move of 9 Parachute Battalion from the drop zone to its subsequent assault on the Merville Battery. It was also responsible for protecting 9 Parachute Battalion’s withdrawal once the objective was destroyed. In addition, the Company destroyed enemy pockets in the nearby Gonneville-sur-Merville area. Upon completion of those tasks, “A” Company was to link-up with the Battalion at the Le Mesnil crossroads.

“B” Company also jumped with the main group. It destroyed the bridges at Robehomme and occupied the road and track junctions in the vicinity. Once the engineers had returned to their post-mission rendezvous point, “B” Company moved to Le Mesnil to take up its position in the Battalion perimeter.

Once the Battalion assembled at Le Mesnil, all mortar, machine gun, and anti-tanks platoon personnel who had been attached to the companies for their initial D-Day tasks were directed to report to Battalion Headquarters so that they could be deployed within the defensive perimeter to best effect. The machine gun and anti-tank platoons were dispersed throughout the rifle companies to provide additional fire support along the front lines. The mortar platoon set up behind the Battalion Headquarters so that they could provide defensive fire anywhere along the unit’s perimeter.

Throughout the next few hours, the ongoing battle at the Varaville Château and surrounding area attracted small groups of paratroopers who had been dropped off course. All moved toward the sound of fighting. Private Cliff Funston was among a group of paratroopers who had finally made their way to Varaville before dawn. “It was rather confusing to tell you the truth,” related Funston. “There was a lot of uncertainty as well as a lack of heavy weapons and men.” Nevertheless, these welcomed reinforcements were immediately fed into the battle.

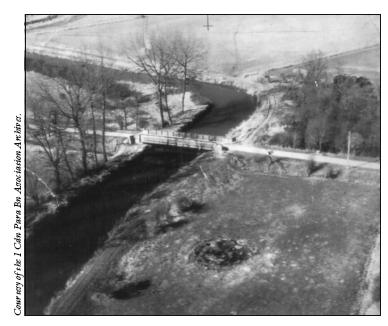

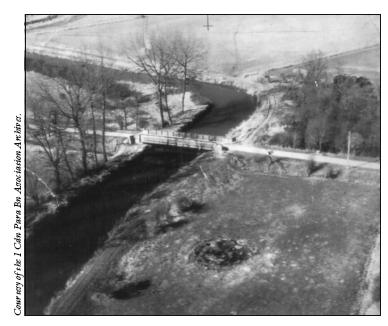

The Robehomme Bridge in Normandy, France. This was the objective of 5 Platoon, “B” Company, on D-Day.

One British airborne captain, who landed in the outskirts of Complete chaos seemed to reign in the village,” Varaville, described the intense fighting. “Complete chaos seemed to reign in the village,” he reported. “Against a background of Bren guns, Spandau machine guns and grenades could be heard shouts in English and German.”

Initially, the German defenders pinned down the paratroopers with heavy machine-gun and anti-tank fire. However, once the enemy’s range and positions were confirmed, the paratroopers replied with well directed anti-tank, mortar, and Bren gun fire of their own. Around 0300 hours, a German anti-tank shell crashed through the Château’s gatehouse, where Major MacLeod and six other paratroopers had set up their anti-tank gun. Upon impact the projectile ignited the paratroopers’ anti-tank shells and grenades. A terrible explosion ripped through the group, resulting in the death of four paratroopers. Of the original six man group, only Privates H.B. Swim and G.A. Thompson survived, but they sustained serious injury.

Despite this terrible blow the battle raged on. As additional paratroopers joined the fray they successfully cordoned off the German defenders. Nevertheless, the enemy was not prepared to surrender. Private Esko Makela, who had been separated from “B” Company, showed up in Varaville as the darkness began to fade. He was ordered to take up a position in the gatehouse and engage the anti-tank gun position with his Bren gun. His arrival increased the amount of firepower and soon the intensity of the fire from the Canadian paratroopers forced the German gun crew to pull back. As the sun rose over the horizon the Canadians could observe the layout of the enemy’s positions and troop movements. “I was then given a rifle,” explained Private Makela, “and I sniped at quite a few heads.”

By 1030 hours that morning, the German garrison of Varaville surrendered. A total of 80 prisoners and walking wounded were corralled. As the prisoners were marched off, the airborne soldiers were surprised by the number of defenders captured. “Two enemy soldiers for every Canadian paratrooper who fought in Varaville,” tallied Corporal Dan Hartigan.

Corporal John Ross, a signalman attached to “C” Company, recalled, “The Germans were mad when they saw that they had been captured by a small group of lightly-armed paratroopers.”“C” Company was ordered to pull out, regroup, and take up a series of defensive positions to guard the roads going through Varaville. By 1500 hours, the first elements of the British 6th Commando Cycle Troop arrived and relieved the Company. The Canadian paratroopers started the final phase of their D-Day mission. They marched to the Le Mesnil crossroads and took up new defensive positions within the Battalion perimeter.

Panoramic photograph taken from a trench in front of the gate house at Varaville. The picture shows Germans surrendering on the left side, and being disarmed on the right.

But “C” Company was not the only subunit to be afflicted by a scattered drop. By 0600 hours, only two officers and 20 paratroopers from “A” Company, as well as a handful of airborne soldiers from other units, had reached their RV. Severely undermanned and behind schedule, Lieutenant J.A. Clancy assembled his small group and headed to the Merville Battery to join the 9th Parachute Battalion. But the drop had also severely hampered the 9th Parachute Battalion, which had been given the critical task of destroying the battery. Only 150 of the 650 paratroopers earmarked for the assault had managed to reach the RV.

Nevertheless, anxious to get on with this important task, Lieutenant-Colonel T.H. Otway, the Commanding Officer, organized his men into two assault teams. They quickly cleared two paths across the minefield surrounding the battery. As they painstakingly inched their way toward their final objective the German defenders, who were positioned in adjoining bunkers and casemates, opened fire with three heavy machine guns. It quickly turned into a blood bath. Seventy British paratroopers were killed in the short, savage battle. Notwithstanding these heavy losses, Otway and his men succeeded in capturing the battery by approximately 0500 hours. Yellow signal flares were sent up shortly after to confirm that the battery had been captured and, more importantly, to cancel a naval bombardment from HMS Arethusa that was planned for that morning.

Upon entering the main structure, the British paratroopers were surprised by the type and calibre of the guns positioned at Merville Battery. Due to the size of battery’s outer structure, Allied planners assumed that it could possibly contain four 150 mm guns, capable of firing 96 pound shells every 15 to 20 seconds to a maximum range of eight miles. The Allied planners concluded that if this battery opened fire it could cause great mayhem on the beaches. They decided that it was of the utmost importance that the battery be neutralized before the troops disembarked on the beachhead. But instead of 150 mm guns the paratroopers only found four 100 mm 1916 Skoda Works Czechoslovakian Howitzers, capable of ranges of up to six miles. Regardless, they had to be destroyed in case the Germans launched a counterattack and recaptured the battery. But the airborne engineers were nowhere to be found. They had been dropped way off course and had not been able to get to their objective. It was up to the paratroopers to demolish the guns themselves. Gathering their Gammon bombs, they destroyed two guns and disabled the others.

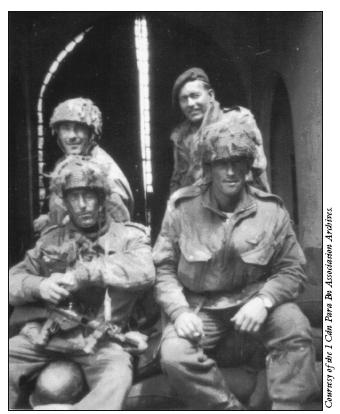

Canadian paratroopers take a brief pause after capturing the French town of Varaville.

Lieutenant Clancy’s group finally reached the Battery as Otway’s men were in the process of securing the perimeter, tending to the wounded, and assembling the prisoners. Their trek had been delayed at Gonneville-sur-Merville because of a heavy Royal Air Force (RAF) bombardment. As the British paratroopers assembled and prepared to move out, Clancy briefed his men. They were to lead the way and protect Otway’s march to their final assembly point, the high ground of Le Plein in Amfreville.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

Gammon Bomb

The British Gammon bomb used during the Second World War was officially known as the No. 82 grenade. It was developed by Captain R.S. Gammon of the 1st Parachute Regiment as a replacement for the temperamental and highly dangerous “sticky bomb grenade.” The Gammon bomb consisted of an elasticized stockinette bag made of dark coloured material, a metal cap, and an “Allways” fuse, which was the same one used in the No. 69 grenade. Unlike other grenades in use at the time, the Gammon bomb allowed the user to determine the amount and the type of explosive that could be delivered to a target. For example, for anti-personnel use a small amount of plastic explosive (about half a stick) along with shrapnel-like projectiles would be placed in the bag. For attacking armoured fighting vehicles, bunkers, or other large targets, the bag could be filled completely with explosives, making an extraordinarily powerful grenade.

The Gammon bomb was also very simple to operate. First, the stockinette bag would be filled with explosive. Then the screw-off cap was removed and discarded. Once the cap was gone a small, stout linen tape that wound around the circumference of the fuse was exposed. The linen tape had a curved lead weight on the end. While holding the lead weight in place with one finger (to prevent the linen tape from unwinding prematurely and detonating the device) the grenade would be thrown at the selected target. Once the Gammon bomb was thrown the weighted linen tape would unwrap in flight, pulling out a retaining pin from the fuse mechanism. The removal of the retaining pin freed a heavy ball bearing and striker inside the fuse, which were held back from the percussion cap only by a weak creep spring. The grenade was now armed. Once it hit its target the impact gave the ball bearing a sharp jolt, causing the creep spring to slam the striker against the percussion cap, detonating the grenade. Gammon bombs were primarily issued by paratroopers and commandos.

As the survivors and walking wounded of the 9th Parachute Battalion headed toward Le Plein, they suddenly came under fire from a heavy German machine gun located in a nearby château. The chatter of the Spandau machine gun cut the predawn stillness. The paratroopers quickly dove for cover and the Canadians quickly spread out and neutralized the enemy position. Following this short engagement, Clancy reorganized his group so that they formed an all around protective shield for the members of the 9th Parachute Battalion during their withdrawal to their new positions in Le Plein. Despite being severely undermanned, the members of “A” Company had successfully completed their D-Day tasks. By 0900 hours, they left their British comrades and rejoined the Battalion at the Le Mesnil crossroads.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

The “Allways” Fuse

The “Allways” fuse was an impact-only fuse. The term “Allways” referred to the fact that the grenade would always detonate, no matter how it hit the target. Normally, impact-detonated munitions had to hit the target with a particular point of impact (i.e., perpendicular to the fuse mechanism) in order to detonate. However, the “Allways” fuse was guaranteed to explode no matter which way the Gammon bomb hit the target (e.g., landing on its fabric base, sideways, or upside down).

“B” Company’s personnel fared no better than the other companies. Only 30 all ranks had managed to regroup at the designated RV. That was less than a quarter of the company strength that had set out. Lieutenant Normand Toseland moved the group toward their objective, the Robehomme Bridge. During their advance they unexpectedly came across a young French girl who volunteered to guide them. At the bridge they met up with two other Battalion officers, Major C.E. Fuller and Captain Peter Griffin, and a mixed group of British and Canadian paratroopers. The small force took up a defensive posture and waited patiently until 0300 hours for the arrival of a team of British airborne engineers.

Growing restless and unsure if the engineers would actually arrive, the group decided to blow up the bridge themselves. Toseland collected all of the available high explosives. The paratroopers prepared a charge and detonated it under the bridge. Unfortunately, the charge was not strong enough to do the necessary amount of damage. Even though the structure had been weakened it could still be used by enemy infantry. Knowing that this blast would surely attract the enemy’s attention, Major Fuller ordered his group to form a defensive perimeter so that they could repel a German attack. As the paratroopers were digging in, a small group of British airborne engineers, led by Lieutenant Jack Inman, finally arrived. They rigged a second charge, which successfully detonated sending the bridge crashing into the river in a cloud of black smoke and debris. With the mission accomplished, the group moved off to the Le Mesnil crossroads.

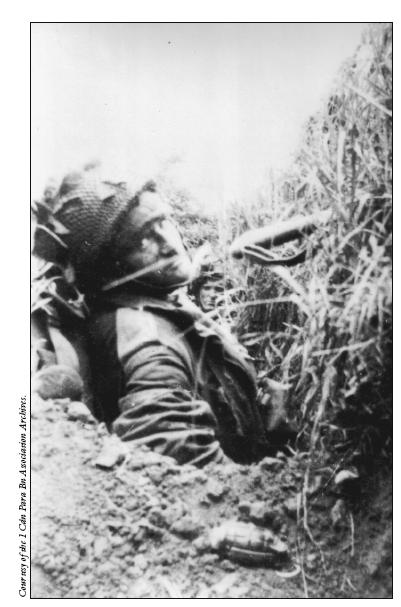

Fatigue proved to be the soldier’s constant companion. The paratroopers were on constant alert to oppose the inevitable German counterattack. A Mills M-36 defensive grenade is in the foreground.

The route to the Battalion’s position was now active with enemy troops. Major Fuller did not have communications with anyone else in the Battalion, so he was uncertain of the status of the remainder of the unit. He decided to use patience and caution. He opted to travel by night and use the terrain to cover his movements. Over the next day and a half, Major Fuller’s group increased to 150 Canadian and British paratroopers as they picked up stragglers. Although he was happy to assemble such a large force because of the security it provided, it also complicated his mobility while behind enemy lines. For added security, he ordered his paratroopers to avoid engaging in combat with the enemy so that they would not comprise their positions. If contact with the Germans could not be avoided, Fuller decided that they would attack and then quickly withdraw.

Fuller ordered a group of 30 paratroopers to act as an advance force to protect the main group and the wounded. Sergeant Roland Larose was part of this band. “As we advanced silently up the road towards Le Mesnil we came across a parked German half-track. We froze instantly. A German officer stepped out and said something to us,” recalled Larose. “My friend Russell Harrison yelled back at him, ‘I beg your pardon.’ Then we opened up and threw grenades into the vehicle.” Within seconds 11 enemy soldiers had been killed.

An hour later the group was called back to provide rear area protection. A German jeep drove up and before the driver could get his vehicle into reverse a volley of automatic fire killed all of the occupants. The ad hoc company group finally reached Le Mesnil at 0330 hours on 8 June.

Even though the parachute drop was filled with many unforeseen complications, such as the wide dispersal of paratroopers and the loss of the majority of their heavy support weapons, it was the composure, stamina, and excellent training of the Canadian paratroopers that allowed them to successfully accomplish all of their assigned D-Day missions. Their ability was so great that even the enemy quickly realized that they were fighting a skilled opponent. The Commander of the German 711th Infantry Division, Lieutenant-General Joseph Reichert, was especially impressed by the fighting qualities of the Canadian paratroopers. He exclaimed, “The Canadian paratroopers fought in an excellent manner both during the attack and the defense.” This certainly was high praise given the obstacles the paratroopers had to overcome: strain and exhaustion from the turbulent aircraft ride, a bad drop, and a lack of heavy weapons and ammunition, to mention a few.

FROM THE INTELLIGENCE FILES

1st Canadian Parachute Battalion Organization

The War Establishment of the Battalion was set at 616 all ranks (26 officers, 73 senior Non-Commissioned Officers, 517 rank and file) within four subunits that broke down as follows:

• Headquarters (HQ) Company (5-20-144) consisting of: Battalion HQ; Company HQ; Signals Platoon; Administrative Platoon (at 77 personnel, it was the largest platoon in the unit); Mortar Platoon (four, 3 inch mortar detachments); HQ Protection Section; and the Intelligence Section; and

• Three Rifle Companies of 139 all ranks (5–16–118), each consisting of: Company HQ with two, 3 inch mortar detachments and an anti-tank section; and three rifle platoons (1–4–29). Each rifle platoon consisted of a Platoon HQ and three rifle sections.

The Battalion weapon holdings were established at 29 light machine guns (Bren gun); ten 3 inch mortars; twenty-eight 2 inch mortars; and ten .55 inch anti-tank guns — later replaced by the Projector Infantry Anti-Tank (PIAT). Not surprisingly, many of these support weapons were often “brigaded” (pooled together in one location) to give the unit greater flexibility and firepower during operations.

The rigorous training and physical conditioning enabled the Canadian paratroopers to endure and, more importantly, overcome the physical and mental hardships they encountered during D-Day, as well as the remainder of the Normandy Campaign. In hindsight, Lieutenant-Colonel Bradbrooke affirmed that the Battalion’s D-Day successes could not have been achieved without such a demanding airborne training regime. “Dropping at night, several hours before the seaborne assault, in strange and hostile territory, all added up to confusion and an appreciation of the reasons why prior training of such severity was necessary,” remarked Bradbrooke.

The young paratroopers also realized the benefits of their earlier demanding training routine in England. “The training you got, the people you trained with, the people that trained you,” explained Sergeant John Feduck,” you might have hated them, but that is why you were there and that is why you were still alive.”

Nevertheless, the Battalion’s initiation to airborne operations came at a heavy price. After the first 24 hours, of the 541 paratroopers who jumped into Normandy a total of 116 all ranks were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. And a great number of paratroopers were still missing. Some were hunted down and captured by the Germans. Those who had landed far from the DZ and sustained serious injuries during their landings or wounded in subsequent firefights, died alone. During the course of the following days, the lucky ones eventually made their way back to Le Mesnil to join the Battalion. However, all those who survived the initial jump quickly realized that the battle had just only begun.

A tired paratrooper mans the front line at Le Mesnil.