X

Travels with “My Aunt”

Actors occupy a peculiar place in the social phylum—people who literally stand out from the rest of the species, wanting to be looked at as much as the rest of us want to look at them. They bring stories to life, tapping into our emotions, often becoming the vessels that allow us to experience a moment of realization, sometimes self-recognition. Many become reference points common to people around the world, elements in universally shared experiences. We tend to look upon the practitioners of the acting profession as special. We pamper and praise them; some people practically worship them.

Then there are movie stars, a breed unto themselves. The stakes are so high for those rare few who, decade after decade, captivate us, that we shower rewards upon them. Some are compensated with millions of dollars for a few days of work; their opinions on all subjects are held in higher regard. We create special rules for them, private entrances and exits for them to pass through.

The lives of the biggest movie stars—the “superstars”—are generally as “unreal” offstage as the characters they portray. There is a near-constant frenzy around them—the whirl of managers and agents and publicists and assistants tending to the constant demands for the star’s time: interviews; photograph sessions; public appearances. The ringing telephone becomes an addiction, often sending a star into withdrawal when it stops.

For those who became famous under the old studio system, the lack of reality to their lives was even greater. Because the contract stars of the thirties, forties, and fifties had worked constantly, everything off the set was less important than what they did before the cameras. The studio heads paying the bills protected their own interests and took care of everything in their stars’ lives. On the set, doubles were always available for the dangerous or unpleasant duties, whether it was performing a stunt or standing under the hot lights. Off-camera, everything was tended to. Not just clothing and grooming and personal chores but even indecent, occasionally illegal, activities were cleaned up, swept under the carpet, fixed.

Many stars begin to believe their own encomiastic press releases. After a year or a decade, and, in a few cases, a lifetime of fabulous salaries and fringe benefits, there naturally comes a sense of great expectations. With most movie stars, there also comes a sense of entitlement.

Perhaps the most attractive aspect of Katharine Hepburn’s personality was that she held no such feelings. She made plenty of demands; indeed, she knew how to get what she wanted long before she was a star. In part, that’s how she got to be a star. But she always remained grounded. In twenty years I never found a trail of bodies she trampled over in order to reach her goal. For all her impatience, there was always a sense of humility and humanity, even a sense of gratitude for her good fortune. She was never above making a bed, cooking a meal, chopping wood, or working her garden. Indeed, she found pleasure in those activities. Almost every time I saw her in the kitchen in Fenwick, she was wiping a sponge across the countertop, cleaning up after somebody.

In short, she never lost her work ethic. She believed the point of making money was to allow you to live comfortably enough to work some more, until you simply could work no longer.

“Retire?” she had exclaimed one night at dinner, when Irene Selznick had found a gentle way of broaching the topic. “What’s the point? Actors shouldn’t walk away from the audience as long as the audiences aren’t walking away from them. As long as people are buying what I’m selling,” she added, “I’m still selling.” Kate never understood how people got stuck in jobs they didn’t enjoy.

Stars who bemoaned the hardships of their profession—the impositions, the loss of privacy—rankled her, as though she were embarrassed to be one of them. “These actors who complain in interviews about twelve-hour days!” she said with incomprehension. “You sit there for eleven of them. It’s not as if we’re carrying sacks of feed all day!”

“What does he expect?” she said upon reading about Sean Penn punching out a photographer. “You can’t go around saying, ‘I’m special. I make my living asking you to look at me, to pay to see me,’ and then get upset at somebody for taking a picture. If you don’t want to be a public figure, don’t pick a public profession and don’t appear in public. Because in public you’re fair game.” She also didn’t understand stars who sued newspapers over printing lies about them. “I never cared what anybody wrote about me,” Hepburn said, “as long as it wasn’t the truth.”

While she sought the limelight all her life, Hepburn believed actors received too much attention and respect. “Let’s face it,” she said once, “we’re prostitutes. I’ve spent my life selling myself—my face, my body, the way I walk and talk. Actors say, ‘You can look at me, but you must pay me for it.’ ” I said that may be true, but actors also offer a unique service—the best of them please by inspiring, by becoming the agents for our emotional catharses. “It’s no small thing to move people,” I said, “and perhaps to get people to think differently, maybe even behave differently.” I pointed out to Hepburn that she had used her celebrity over the years for numerous causes—whether it was marching in parades for women’s equality or campaigning for Roosevelt, speaking out against McCarthyism, or supporting Planned Parenthood. “Not much, really,” Kate said. “I could’ve done more. A lot more. . . . It really doesn’t take all that much to show up for a dinner with the President or to accept an award from an organization so it can receive some publicity. Oh, the hardship! Oh, the inconvenience! Oh, honestly!”

Los Angeles is, in many ways, a one-industry town. There is, obviously, a thriving financial sector; real estate, aerospace, and the music business have all played a large part in the economy and ethos of the city. But motion pictures dominate, pervading all walks of the city’s life. Photographs of movie stars decorate the walls of liquor stores, restaurants, even car washes—with best wishes from the likes of Burt Reynolds, Zsa Zsa Gabor, and Rock Hudson. Although most people in Los Angeles have never met a movie star, everybody there seems to “know” them all—through a common trainer or hair stylist or florist or dry cleaner or checker at the supermarket.

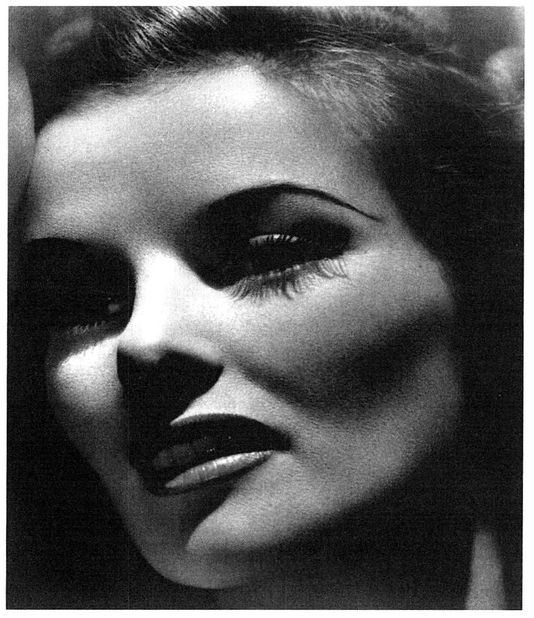

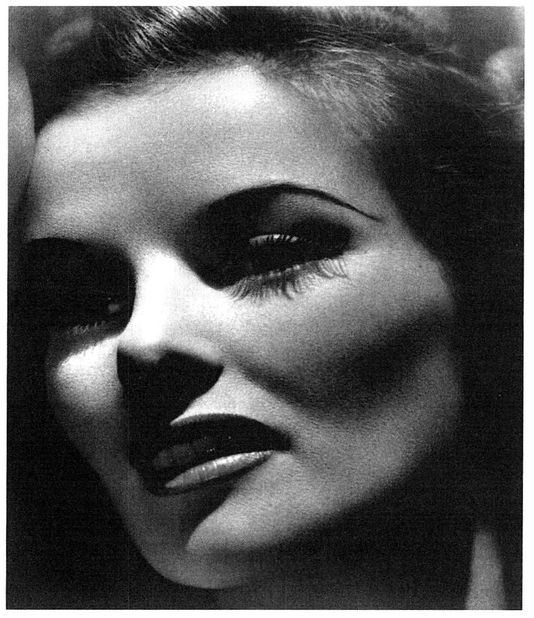

For close to seventy years, Katharine Hepburn sightings remained the most coveted of show-business personalities—even more than those of Garbo, who could be counted on to take her daily constitutional on the streets of New York. One rarely heard a firsthand Katharine Hepburn story. Although some of my friends knew of my relationship with her—mostly because her name appeared on the dedication page and in the acknowledgments of Goldwyn—few ever invaded her privacy by even asking me about her.

Although I had “known” Warren Beatty through several friends and my older brother, Jeff, the head of International Creative Management, a major talent agency, I had never met him until early 1993. Then I began receiving calls from his wife’s agent. He said Annette Bening had long been fascinated with Anne Morrow Lindbergh, and she was hoping I might be able to meet her sometime to talk about what I had gleaned from the Lindberghs’ private archives. An insistent third call from the agent expressed the fact that Warren Beatty was eager to meet me as well and that somebody would be calling very soon to arrange a dinner. Five months passed in which I heard nothing.

In mid-July the agent called again to set our date. I said this no longer seemed like such a good idea, that after half a year there seemed something slightly forced in the situation. No, the agent explained, Warren Beatty was extremely interested in our meeting. I had not heard from anybody, he explained, because Warren had, in fact, been occupied producing, rewriting, and starring in a film called Love Affair. It was a remake of the 1957 movie An Affair to Remember, which starred Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr, which was a remake of Love Affair, made in 1939 with Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne, all based on a story by Mildred Cram. He and Annette, I was told, very much wanted to get together as soon as possible.

On Wednesday, July twenty-first, Kevin McCormick, a film producer who had recently become an executive at Twentieth Century Fox, and I drove from our house in the hills above the Sunset Strip to Mulholland Drive, where we were buzzed through the Beattys’ gate at exactly seven-thirty. In the living room, we found Warren playing with his eighteen-month-old daughter, entertaining two other guests, the agent and a female executive from another studio. Annette darted in, to say hello, and then went to put her daughter to bed. For several minutes, our host chatted with all of us; then we repaired to the dining room for dinner, where Annette joined us. Few movie stars look as good in person as they do on screen, where they benefit from makeup and lights. The Beattys, however, did. He was taller than I had expected, and his face was starting to show some attractive character lines I hadn’t seen on film. She glowed.

The house was comfortable and unostentatious—though the dining-room ceiling could be retracted, letting guests feel as if they were outdoors. We ate “indoors” that night, a tasty but extremely dietetic meal of chicken and vegetables and a fruit dessert. A bottle of wine sat on the table, but neither of the hosts indulged, imbibing only water. Conversation quickly turned to my work on Lindbergh. Annette and the three other guests just sat and ate, as Warren peppered me with questions about the famous aviator. He was surprised (and pleased) to learn that the story included so much politics, starting with Lindbergh’s grandfather (who had been elected to the Swedish Riksdag and had been forced to leave his homeland because of a political and sexual scandal), including Lindbergh’s father, (who had been a controversial five-term Congressman), right up to Lindbergh himself, known for his role in the little-understood America First movement. I tried to include everybody at the table in the discussion, often lassoing Kevin in for his astute political commentary. But Warren was not much interested. That night I was the only person on whom he fixed his attention.

A little after ten, the conversation changed, but the conversants did not. While the other guests grew restless, our host shifted the dialogue to Goldwyn. “Is it true I was the last person Sam Goldwyn talked to before he died?” Beatty asked me. Not quite, I explained. But Warren Beatty had, in fact, been the last name recorded on Goldwyn’s telephone sheet before suffering the stroke that ended his career. Then, just as the other guests were getting up from the table—bored to tears, I feared—the conversation took another sudden shift.

“I guess you know Katharine Hepburn pretty well,” he said. “Because I see you dedicated your book to her.” While Annette started shepherding the others toward the door, Warren lingered behind with me, quickly measuring the depth of my friendship with Kate. “Do you think she’d like to work again?” he asked. Not right away, I said, as she had recently finished a rather uninspiring television movie. “Well,” he followed up, “do you think she’s able to work again?” I said she was definitely capable, but her interest was waning along with her health. She had skin cancers on her face, she was not sleeping soundly, and was suffering from dizzy spells. Her shaking often became more pronounced, I said; and she had taken to working off cue cards. “Oh, that doesn’t matter,” Warren said. “Jack uses them too”—meaning his friend Mr. Nicholson.

“Because there’s a great part in our movie,” he continued.

“The old aunt?” I asked, slightly incredulously. “Is that really a great part?”

While the old aunt in Love Affair was but a supporting role, the character did serve as a kind of fulcrum, appearing in one extended scene in the middle of a sentimental story about a longtime bachelor about to marry. This man-about-town meets a singer, also about to marry, on a cruise; and their sudden love for each other becomes apparent during a brief layover at a European port, where they meet the man’s elderly aunt, who is charmed by the young woman and wishes them Godspeed. (The ageless beauty Cathleen Nesbitt played the part in the Cary Grant version, the character actress Maria Ouspenskaya played opposite Boyer.) In this new version, the port-of-call had become Tahiti, the exteriors of which had already been shot. Beatty told me that Hepburn would have to travel no farther than the Warner Brothers lot in Burbank, where her character’s house was being built on a sound stage. Her dressing room would be constructed literally steps from the set.

“Even if she wanted to work again,” I told Warren, “you’ve got to remember that Hepburn has never played anything but the female lead. With the exception of her scene in Stage Door Canteen, she has always been the star. No supporting roles. No cameos. No commercials. And the only reason she did Stage Door Canteen was as part of the war effort.” This picture, I thought, isn’t exactly in the national interest.

As he and I made our way out to the driveway, where the other guests were driving off and Kevin was talking with Annette, Warren explained that the film was virtually finished except for this one long scene—which required an actress of stature. Moreover, he said, he wanted an actress in her eighties who looked as though she was in her eighties—not an octogenarian who had been tucked and pulled nor a sexagenarian caked in makeup. Not only that, he said at last, “I’ve always been in love with Katharine Hepburn.”

Ever since he had been a young man, he said, she had bowled him over—with her brains, her beauty, and her attitude. “She’s very sexy,” he said.

“That’s what Howard Hughes thought,” I replied, knowing that Beatty had talked of producing a film about Hughes for more than a decade. “Yeah, what about that?” Warren said, as I was getting into the car, which Kevin had started up. “Did she ever talk to you about Hughes?” After I told him that she had, I could see he was prepared to pump me all night. I figured the only way we could leave was if I threw him a bone. So I said, “Kate often told me, ‘What you must always remember about Howard is that he was deaf. And from an early age that affected him.’ ” As the car began to move, Warren followed along for a few paces, continuing the conversation—mostly about how chancy a sentimental love story was these days.

“Well,” said Kevin as we reached the end of the driveway, “—now I see what that dinner was all about.” I said he was being ridiculous, that the purpose of the evening was to learn about Lindbergh, and now that Warren had heard all I was willing to impart, that would be the last I would ever hear from him. We arrived home at eleven.

At 11:05, the phone rang. Kevin said, “Warren.”

“This is Warren Beatty, the movie star,” said the exuberant voice at the other end of the line. “It was really great meeting you guys,” he said. Then he chatted aimlessly about Lindbergh for a few minutes before asking, “So do you think Hepburn might be interested in doing this part?” I reiterated that it seemed unlikely, but I volunteered to inquire discreetly. “This much I can tell you,” I added. “Don’t approach her right away. She likes to feel she’s coming in to save the day. She loves to save the day.” In the meantime, I advised him to tailor the scene in ways that might especially appeal to her. I further advised that he think of other actresses who could play the part, so that he wouldn’t be stuck in the probable eventuality that she wouldn’t do it. Obviously, Beatty had already compiled such a list.

I pushed Frances Dee, Hepburn’s costar in Little Women, saying that I had seen her in recent years and that she was an extremely attractive older woman with all her wits. “I know,” Beatty said, “but I think the part needs a bigger name, a real star.” I mentioned Luise Rainer, who had won back-to-back Oscars in the 1930s—for The Great Ziegfeld and The Good Earth—and who was also in her eighties. Furthermore, I argued, she had been off the screen for decades, so the studio could probably get some publicity mileage out of the casting. “No,” Beatty whined, “she just doesn’t seem right.” I argued that the part sounded more appropriate for her than for Hepburn. “I could see Luise Rainer languishing in her final days in Tahiti,” I said, “but not Kate. No balmy breezes for her. Greenland, maybe. Or the Yukon. But not Tahiti.” That seemed like a frivolous technicality to Beatty, who added, “I just don’t see Luise Rainer as my aunt.”

“I’ve always found Hepburn really sexy,” he told me again. In that moment, what I had long known became perfectly clear. I realized that even for movie stars, Katharine Hepburn was the actress they all wanted to meet and the one with whom they all dreamed of working. Once again I said I would sound Hepburn out but that he should also think about Wendy Hiller, Loretta Young, Jessica Tandy. “The old lady lives in Tahiti,” I suggested before hanging up; “how about Dorothy Lamour coming out in a sarong?”

I called Kate the next morning—waiting until seven-thirty Los Angeles time, knowing that one could no longer call her “at any time.” In fact, she often didn’t awaken until eight, sometimes nine, and then she lingered in bed reading, writing, and sorting through her mail. I told her about my evening with Warren Beatty and his interest in getting her in his movie. “Tell him you spoke with me,” she directed, “and that I have absolutely no interest in the film. Is that the one where the girl gets hit by the car on her way to the Empire State Building?” she asked. I complimented her on her memory. She seemed to have been approached to appear in this version of the film already, and she wrote the story off as “pretty silly stuff.”

“My God,” she added. “Have I become Maria Ouspenskaya?”

Strangely, our conversation on the subject did not end there. “Is he interesting?” she asked, indicating Warren Beatty. “I’m not sure,” I said. “He’s certainly engaging. He gives the big rush. And he has a kind of courtliness. I think you’d like him.”

“Why does he want to remake that movie?” she asked.

“Cary Grant, I think.”

“Cary Grant?”

I told her a story I had heard years earlier about Cary Grant walking into a big Hollywood party in the sixties, where he saw all the gorgeous women in the room swarming around the young Warren Beatty. Grant was said to have commented to a friend, “See that guy. That used to be me.”

“Now,” I told Kate, “I think Mr. Beatty wants to be Cary Grant. No man aged more gracefully on the screen than your friend Cary, and when he was fifty-three he made An Affair to Remember.”

“How old is Warren Beatty?” she asked.

“Fifty-six.”

“Is he any fun?” she asked. “I’m not sure.” I said. “He takes himself extremely seriously, but I think that’s so people around him will take him seriously. But I have a hunch he’s kind of goofy underneath it all.”

“Hmmm,” Kate said. “Well, that could be fun.”

I reported most of the conversation to Warren and suggested that he leave her alone as long as possible, that in closing the door she had left a slight crack. It was a clear signal that Hepburn was ready neither to end her career nor to commit to anything new. I told him that I would be visiting her in New York in early September and I could take her pulse in person.

At that dinner in New York, I raised the subject of the Warren Beatty movie. Again she was noncommittal. With such a small role, she asked, what was the point? I said that it might be fun to do such a part—one that would make a great impression and wouldn’t require much time or effort. Besides, I argued, it would be nice circumstances under which to visit her friends in Los Angeles, something she hadn’t done in years. “They’re all dead,” she said.

“Well, I’m not,” I protested.

“If you keep talking about this movie,” she said, “you will be.”

Most people, even in Hollywood, don’t know exactly what a producer does. In fact, producers come in all varieties and perform any number of functions. Some seize an idea or get their hands on a piece of unpublished material and shepherd it to a studio, where they develop it as a motion picture; others simply raise the money for the venture. Studios often stir other producers into the stew because of their ability to lure big stars and prominent directors. Still other producers get assigned to a film because of their ability to “make the trains run on time,” seeing that the dozens of artists and technicians and drivers and caterers all perform their tasks according to the budget. Such extensive division of labor accounts for the large number of producers one finds in the credits of motion pictures today.

In the golden age of Hollywood, each film generally had one producer, and perhaps an associate who monitored the mechanics of the physical production. In more modern times, there are very few producers who conceive a film project and oversee its journey from inception to exhibition. The conglomeratization of the studios is, in part, the reason for the increase in number of producers—as bean-counting corporate heads want to insure their ever-increasing investments by hiring high-paid specialists to perform each production task. Another reason is that there’s little room for the big personalities that existed in the old studio system—men like Goldwyn and Selznick and Thalberg, whose passion practically willed their movies into existence.

Not long after remaking Love Affair popped into my life, I asked a venerated member of the Hollywood community what he thought of Warren Beatty. “As an actor,” he said, “he had one of the greatest ten years an actor could have. And since then, his career has pretty much slipped, and so has his acting. As a director, he’s had a couple of good pictures. But as a producer, he’s one of the best I’ve ever seen in this town. He can get anybody to do anything. That’s producing.”

Into the fall of 1993, I watched Warren Beatty produce. He made contact with Hepburn herself and her no-nonsense financial adviser named Erik Hanson. Upon learning that Kate liked cut flowers, Beatty began sending arrangements—one after another. I too began to receive his calls. At first they came once a week, to devise a game plan; then once a day, soon five times a day, analyzing every word she had said to him and strategizing every word he might say back. The calls were always flattering and full of excitement, manipulation so overt that it was comical. Kate was amused as well and called one morning to say, “Please tell your friend Mr. Beatty to stop sending me flowers. It looks like a funeral parlor around here.”

She clearly enjoyed the seduction; but as December arrived, the courtship had to end. The film’s remaining scenes had to be shot—with or without Katharine Hepburn. Feelers had been put out to Frances Dee, who was standing by in case her old friend Kate declined.

Meantime, Hepburn’s health was failing. Her energy was not what it had been even the year before, and her short-term memory came and went. She found it difficult to concentrate. She asked what I thought of the script, as she could make little sense of it. When I told her I had not seen it, she asked me to call Warren Beatty and request a copy.

I did, suggesting that Hepburn herself realized that this might very well be her swan song and that she wanted it to be special. Toward that end, I said he should consider interpolating a few lines that would be “personal”—not just in style but also in substance. I was thinking of dialogue that might comment upon the character’s life and philosophy but which was obviously drawn from Hepburn’s as well, rather the way Spencer Tracy had spoken his heart in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

Beatty messengered a script over—not the entire script actually, just the fifteen pages that featured old “Aunt Ginny.” They didn’t seem like much to me. In the first of my calls from Warren the next day, I asked, “Who wrote this?” The simple question elicited a most complicated answer—of the sort one found in most of his interviews, rambling and evasive: “Oh, it’s really hard to say. A lot of people have had their say, and of course it goes back to the original movie and Mildred Cram and . . .” The best I’ve gathered since is that Robert Towne wrote the script with Beatty rewriting, or vice versa.

Hepburn also called that day and asked what I thought of the script. I said I thought it was pretty mediocre, flat and charmless. “I thought I was the only one,” she said. “That puts an end to that.” But, I added, there was still plenty of time to fix it, because it was a potentially wonderful scene. “What’s the point?” Hepburn asked. “Why bother?” The fact that she even asked, that none of her refusals to do this movie had sounded definitive, made me think she really wanted to take the job. If they could have shot the scene in New York, I don’t think she would have hesitated for a moment. But this would mean uprooting herself and moving to California for several weeks; and I think that, for the first time, she was factoring her age and health into the equation. Beatty promised to find her a comfortable house, one that could easily accommodate Norah and anyone else with whom she wanted to travel. Of course, she could select the personnel tending to her hair and makeup and costumes.

Kate seemed to be wondering if she would be alone during this venture. Laura Harding had been there for her in the old days, but she was estate-bound in New Jersey; Phyllis had become too feeble to make the trip; and Cynthia McFadden, who had become Kate’s favorite companion on both business trips and vacations, could no longer simply take time off from work. When Kate asked again what the point was in doing the film, I felt she was asking whether or not I would be around.

“I think you should do it,” I said. “You always said, ‘Actors act.’ So I think you should act. Do you need this movie for your career? I don’t think so. But I think it could be fun, we can have some adventures in L.A., and you’ll be starting your seventh decade in movies. Now that’s pretty great—a career that goes from John Barrymore to Warren Beatty.”

“Jesus!” she said. “I might have to say ‘yes’ just to stop him from sending any more flowers.”

“I believe that’s part of his campaign, Kate, to show the kind of attention he’ll lavish upon you.”

“We’ve run out of room here,” she said. “So it shows me that he’s a goddamned fool for wasting so much money.”

I updated Warren Beatty, explaining that Kate would probably flip-flop another dozen times in the next two weeks and that left to her own volition, she would prefer to stay at home. “She is eighty-five,” I reminded him. All that said, I told Beatty that I would be willing to fly east to reassure Hepburn of the soundness of this venture and that I would accompany her to Los Angeles. I also said that if he wanted to act on his own, that would be fine with me as well. In any case, I added, “you really should let up on the flowers.”

Christmas Day, a Saturday, Beatty called to say if my offer still held, we should leave on Monday, the three p.m. flight. Hepburn still had not committed to the role, but her deal had been negotiated, her backup team was on alert, and accommodations were being arranged. We just had to lure the lion out of her lair. Because we would be arriving in New York long after Hepburn’s bedtime, I asked him to book a hotel room for me on Monday night and to make a dinner date with Hepburn for Tuesday. Meantime, I would call Kate and arrange to be with her Tuesday afternoon to discuss the trip. I would stay for dinner, and spend the night upstairs—because Wednesday morning she would rise with absolutely no intention of leaving for California.

Monday morning, Beatty called to say a car would pick me up at two o‘clock, return to his house to fetch him, then we’d go to the airport. “Isn’t that cutting it a little close?” I asked. He said he didn’t think so, but I could have the car come whenever I wanted. He asked if I would bring a copy of Hepburn’s Me, which he had not read; and for comfort’s sake, I asked for an extra fifteen minutes. That quarter of an hour proved worthless, because when I arrived at Beatty’s house on Mulholland, he was still running around gathering things for the trip and fielding phone calls. We met in the kitchen at 2:15, where he insisted we eat some roast-beef hash the cook was preparing. At 2:25 I suggested we move along if we were to catch our three o’clock flight. “Okay,” he said, downing the last of the hash.

At five minutes before the hour, we arrived at the American Airlines terminal, where a special representative met us curbside. We must have walked through security, but I don’t remember it, as we were escorted right onto the plane. The first-class stewardess had our names and greeted me and Mr. Mike Gambril—the name of Beatty’s character in the movie. The first-class section was empty except for us; and Warren used the flight to whip through Hepburn’s book, periodically asking for amplification on one chapter or another.

We were whisked through JFK and taken to the Carlyle Hotel, where I was shown to an enormous suite—a big bedroom, two baths, and a huge living room—easily costing $1,000 a night. It was only nine o’clock California time when Warren rang and asked me to accompany him to P. J. Clarke’s for a bite.

The restaurant was quiet at that hour, except for a rowdy group of young Italians sitting a few tables away. They periodically pointed to my dinner companion and chanted, “Deek Tracy! Deek Tracy!” Our chatty waitress kept lingering at our table; and when she brought our salads, she seized the moment to ask Beatty if he remembered her. She said they had “dated” some ten years prior. He said he did remember her, which put a big smile on her face; and when she left, he told me that even though she had put on some weight, he did recognize her. As we were leaving the restaurant, one of the Italian men asked “Deek Tracy” for his autograph, which Beatty happily provided. “Where does Hepburn go out to eat?” Warren asked as we headed out.

“She doesn’t,” I said.

“No—I mean, when she goes out, what restaurants does she go to?” I explained that she hardly went to restaurants at all, maybe three in the last twenty years, and only once in the last decade that I was aware of. “Why?” he asked in disbelief. “First of all, she knows she’ll get better food at home. And she also knows that people will be watching her every time she lifts the fork. And then there’s those guys,” I added, pointing back to the jovial Italians. Warren laughed, put his arm on my shoulder, and said, “That’s the reason I do go out to restaurants.”

It was after one when we returned to the hotel, but it was still early on Warren’s wristwatch. Although it was already evident that alcohol was not part of his diet, he asked if I’d join him for a drink in the hotel bar. “What do you drink?” he asked; and I told him a single-malt Scotch or Famous Grouse. “What does Miss Hepburn drink?” he asked. The same, I said. He ordered two Famous Grouses. “How do we like it?” he asked me. Neat, I said. “Neat!” he called out to the bartender, delighting in making his request. For the next hour we sat at the bar—“Another!” he called out with glee—and he was warm, funny, self-deprecating, inquisitive, and positively reverent every time he spoke of Hepburn, to whom he hoisted the second glass.

The next afternoon I went to Turtle Bay with my overnight bag, parked it downstairs in case the plan backfired, and went to the living room where I found Kate examining the script of Love Affair. “I have no idea what this scene is supposed to be about,” she kept saying. “Let’s ask him when he gets here,” I said, “and see if it can be rewritten.”

Beatty was all charm at dinner, attentive to his hostess and even a little nervous. He spoke of the house he had found for her in California—not far from the studio and even closer to his house, at the top of Benedict Canyon. The Warners’ private jet, he said, would be available at noon to fly us to Burbank. Norah was in a swivet, barely able to keep her eyes off him as she ran trays up and down the stairs. I asked if there was still time to tinker with the script; and the producer and cowriter assured Kate that she would not have to film a word of it until she was satisfied. Hepburn came around. She said she would fly to California and appear in the picture. A little after eight, she was ready to retire and asked where I’d be spending the night. I said that Warren had a suite at the Carlyle for me but that I would prefer to stay on the fourth floor. “Good idea,” she said. “Save the forty-five bucks!”

“Forty-five bucks?” I laughed. Realizing she was way off, Kate tried again. “Sixty-five?”

Kate said her “good nights” and went upstairs, followed by Norah, who had already packed most of Hepburn’s clothes for the journey. I went downstairs to get my bag and to show Warren out. He felt good about the way the evening went. “But listen,” I said. “It’s not over. She’s going to wake up tomorrow and refuse to go.” I suggested he put Erik Hanson on alert, and I told Warren to be ready to return to the house himself at nine for the final round of persuasion. Winter weather had arrived in New York, and Norah beamed at the thought of three weeks in Los Angeles—with Warren Beatty no less.

The next morning I went downstairs at seven-thirty to get my breakfast tray, which I brought up to Kate’s room. She was propped up in bed, pouring another cup of coffee and poring over the script. “It’s really terrible,” she said. “I read it and read it, and it makes absolutely no sense. Here,” she said, throwing her copy across the bed, “you play it.” I acted out the scene, which included some drivel likening the promiscuous Beatty character to a duck. Kate rolled her eyes. “It’ll be fine once you get out there,” I said reassuringly.

“Out where?” she asked blankly.

“L.A.”

“L.A.? I’m not going to L.A.” I said I was under the impression she was, that she had told Warren Beatty that she was, and the Warners’ jet was scheduled to take off at noon. “Well,” she insisted, “I will not be on it.”

The next few hours were bedlam. I called Warren a little after nine, and when the operator patched me through to his room, it sounded as though I had awakened him. I said he had better come over right away, that Hepburn was back at square one. He said he would be there in an hour. I suggested he get Erik Hanson over to the house as well. Norah efficiently finished Hepburn’s packing and put the house in order. I continued to tell Kate that she should make the trip and that she could “get sick” and return home if she wanted, but that it might just be some fun.

She would not budge, clearly waiting to be wooed one more time by Beatty. He arrived a little after ten, and restated how important it was to him and the movie that she appear. But it really wasn’t until Erik Hanson, the financial adviser, arrived that she was moved into action. In a sharp tone, he argued that there was no good reason for her to stay home, that she had nothing to do there but sit around and look at the same four walls. Here was an opportunity, he said, for her to travel in great comfort and work under ideal circumstances. A little before noon, Norah, Warren, Kate, and I were packed in a limousine on our way to the airport—in dead silence.

Kate looked miserable, sad and tired, like some exotic animal that had been bagged. “Now Warren,” I asked, for Hepburn to hear, “if at any time, Kate wants to come home, she can come home, right?” Right, he said; he’d arrange for the jet to take her back. “And there’s still plenty of time to work on the script, right?” Right. “And there’s plenty of time to get the costumes fitted, right?” Right.

The stewardess greeted us as we entered the Warners’ jet; and as soon as we had settled into the comfortable seats, we took off. A buffet of salads and meats was set up; and it was one of the few times I saw Kate eat food that hadn’t been prepared in her own house. After lunch, she looked exhausted and said she wanted to lie down. Norah covered her with a blanket on a daybed in the front of the cabin, and she fell asleep. During the flight I spoke to Beatty about the script. He asked a few questions about Hepburn’s career, which made me think he might be rewriting some of her dialogue. He brought up Elia Kazan’s name, not realizing that Kate had worked with him. Kazan had, of course, unleashed Beatty onto the public in Splendor in the Grass, a galvanic film debut. “Kate was in his other ‘grass’ movie,” I said, The Sea of Grass. After a two-hour nap, Hepburn awoke—her face looking somewhat the worse for having slept on it, irritating some of its small lesions. A look of shock came over Beatty.

He spent the balance of the flight making conversation with Hepburn, trying to get her to warm up to him. As I sank into a nap myself, I heard only his icebreaker: “I was just thinking,” he said, “you and I both did Elia Kazan’s ‘grass’ movies.”

Later in the flight, while I was sitting with them, he brought up the name of Shirley MacLaine. “Bad girl,” Kate said, presumably remembering something she had heard, because I didn’t think they had ever met. Warren dropped the subject. A few minutes later, when he changed seats, I told Kate that MacLaine was Beatty’s sister. “Oh dear,” she said, then laughed for the first time that day.

Upon our arrival we were ferried off in limousines—our luggage in a separate car—to a secluded, spacious house at the top of Benedict Canyon. It seemed to meet all of Hepburn’s criteria. It sat behind a gate and had a beautiful tree in the courtyard; the rooms were large and bright, with comfortable furniture in neutral colors; the large master bedroom was within shouting distance of what would be Norah’s bedroom, and it opened onto a large patio with a pool; the living room had a big fireplace. Norah was giddy, having left slushy New York behind her; and when Warren told her a team of assistants stood at the ready to run any errands, I could practically see her praying for the filming to go over schedule. After walking through the house, Kate said, “It’s awful. Let’s go home.”

Promptly insisting he would find her another house, Beatty asked what the problems were. The chair in the living room was in the wrong place for her to enjoy the fire, and the house looked too boring and bare. I suggested that Beatty leave her alone for a few hours, to allow her to make it her own. When he returned, I was just moving a potted tree from another room onto a low ledge by the fireplace, and Kate had showered and changed into a crisp white outfit and was holding a Scotch, sitting in a comfortable chair that had been moved to face the hearth.

The three of us ate a small dinner, after which I said I had to go home. Hepburn had assumed I was staying at the house, but I explained that I lived only ten minutes away myself, that Norah was on the premises, and that I would be back the next morning for breakfast, as though we were in New York together. I asked if the assistant on duty could drop me off at my house, but Beatty volunteered to drive me. We were hardly out the driveway, when he said, “My God, her face looks like a fruitcake. Is it always that bad? What is it, skin cancer?” I said the blotches were probably the result of many years of outdoor sports. “And what is that grease she puts on her face?” I said that it was some formula she had been using for years, really little more than petroleum jelly with lanolin. “My God,” he said, “that can’t be good for her.”

As soon as we hit Mulholland Drive, he reached for the car phone and called a doctor, who immediately got on the line and to whom he described her condition. They began to discuss long-term treatment for Hepburn’s condition and short-term remedies in the week they had before shooting. When he had finished his call, he told me that he had an active interest in medicine, that he tried to keep up-to-date on all the latest cures and treatments and which doctors and hospitals were best in their fields. “Are you a hypochondriac as well?” I asked. He laughed and said, “A little.”

I asked Beatty what the schedule would be like for Hepburn during this week before shooting, as the most important thing for the moment was to keep her occupied. “Her life may have slowed down in New York,” I explained, “but she has a routine there, and all her time is accounted for. So I think you should make sure there’s some activity for her every day.” I explained that until she was before the cameras, I could be there to have breakfast with her every morning and dinner at night, but that he would have to see that her days were filled. He said there would be no problem—what with showing her the set, costume fittings, and the like.

He dropped me off at my house, and I said I would be at the Hepburn Command Center at eight the next morning. As I got out of the car, Warren leaned to the right and yelled through the passenger window, “I don’t know how to thank you.”

“Look,” I said, “I’m doing this mostly for Kate. But think of something.”

With that, he turned off his motor, got out of the car, and rushed over to give me a bearhug. Then, without a word, he drove down the hill toward home.

I spent a few hours every morning that week at Hepburn’s house. Trying to duplicate our regimen, I sat in her bedroom while she finished breakfast and we discussed the newspapers. She seemed tired and disoriented and unsteady on her feet. Thinking part of the problem was that she wasn’t getting any exercise, I took a long swim every day; and a few times I was able to induce her into the pool as well. Although Beatty did come up with an activity each day, that still left the bulk of the time unfilled, with nothing for Hepburn to do but sit around and moan. She suffered from spells of vertigo.

Even so, late mornings she wanted to go out on drives. I thought they would exacerbate her dizziness, but she said inactivity was worse. The first day she wanted to look at some of the houses in which she had lived. I drove her to the cottage she shared with Tracy on the Cukor estate, which had recently been bought and remodeled into a charmless house. It bore so little resemblance to what it had been, Kate had no idea where we were until she looked at the street sign. “Do you know who lives there?” she asked. No, I told her; but I was sure they would be thrilled to let her look around if she wanted. “Let’s,” she said. As I got out of the car, I saw her staring sadly at the place. As I opened her door to help her out, she said, “Let’s not.”

We drove up Doheny Drive a few blocks, to my house—three stories perched on stilts, modern, and with a big view of the city from the mid-Wilshire area to the ocean. It was a beautiful clear day. She got as far as the entrance on the top floor, marveled at the vista, and said, “Where’s the fireplace?” When I told her I had none, her interest in the place waned. I started to lead her down the stairs to show her the rest of the house, especially my office. Not two steps down, she changed her mind. “I’d rather not know,” she said, beginning a familiar refrain.

“Know what?” I asked.

“That you live somewhere,” she said in a slightly wistful tone.

She wanted to leave the house right away and carry on our tour of the canyons. Hepburn remembered every turn up every small street, stopping at one address or another, seldom getting more than a glimpse of a driveway. Later in the ride, she asked out of the blue, “How can you live in a house without a fireplace?”

That night Annette Bening accompanied Warren to Hepburn’s house, and the four of us had dinner. The meals Norah prepared were the same she served in New York. Annette was charming and courtly with Hepburn. When she and Warren left, Kate asked, “Who’s the girl?” That, I explained, was her costar in the movie—a very good actress and Warren Beatty’s wife. “His wife!” she said. “He has a wife?” Yes, I explained; after years of his being Hollywood’s most eligible bachelor, with countless celebrated romances, he married her. “Poor girl,” said Kate. I asked why she said that, that I thought they both seemed in love. “Hmmm,” observed Kate. Then, without missing a beat, she added, “With the same man.”

The second day our driving tour took us to the top of Tower Road. She wanted to see the wonderful house in which she had lived in the thirties, one later owned by Jules Stein, the founder of MCA, the entertainment empire. She asked who the current owner was, and I said, Rupert Murdoch. “Hmmmm,” she nodded knowingly, “this is a place for somebody who feels that he owns the world.” Big gates with the letter “M”—reminding me of the gates outside Xanadu in Citizen Kane—barred entry onto the property; but Kate asked me to try to get us in. I buzzed a half-dozen times from the gate, but there was no response. “This is New Year’s Eve,” I said. “Everybody’s probably away.” That was good, she said, instructing me to drive around to the back of the property. There was a chain-link gate ajar, through which we were both able to squeeze, thus setting foot on the grounds. After a few steps, however, we were met by a more formidable fence.

“We need some of those big wire-cutters,” she said. I apologized for not traveling with metal shears. “What about a bat, or something,” she said, suggesting that we could probably pry the locked gate open. After I struck out again, she scrounged around for a big stick. Not until we had rattled the chain-link fence for several minutes did she abort our mission. We tried the front gate one more time, then retreated down the hill.

Before going out to a New Year’s Eve party that night, I returned to Kate’s house to have dinner with her and the Beattys—at five-thirty. In honor of the occasion, Kate had me open a bottle of champagne. We all hoisted our glasses to good things in 1994, all except Annette . . . who at the last minute picked up her glass and, as though talking to herself, quietly said, “Well, the doctor said a small glass of wine would be all right.” It would not make the columns for a few months, but I drove off that night thinking the Beattys were expecting a second child.

That weekend, just before she was to begin shooting, Kate talked of going home. She said she was tired of Los Angeles; and the deal was that she could return whenever she wanted. Over breakfast the conversation veered to where it had been weeks ago, to the script. We read her scene aloud, and she kept saying, “It just doesn’t make any sense.” I asked her what was unclear and suggested she improvise some dialogue of her own. She asked me to do the same. “Why don’t you tell him,” she said, referring to Beatty, “that you and I discussed the script, and you’ve come up with a few suggestions that you thought would help the film.” I said that as the star, producer, and cowriter, he might not take kindly to “my” suggestions, but that I would speak to him.

After I had typed up the fresh pages, Beatty asked me to come to the house to discuss them. He said he liked them, then insisted on discussing even the most innocuous lines, word by word. I suddenly realized why so many years elapsed between each of his pictures. Then he asked what the possibilities were of her saying a line in his version of the script, “Fuck a duck.”

I asked him what the point was, as the line was neither necessary nor funny and was, frankly, a little tasteless. “But would she ever say it?” he asked. I said the sheer shock value of the line would probably hold some appeal for Hepburn. In Coco, I told him, her character had come down a staircase after a fiasco of a fashion show and said, “Shit!” I also said that, while that had been some twenty years earlier, she had disappointed a lot of fans. “But do you think she’d say it?” Warren repeated, clearly intent on working the line into the script. I said she probably would, but why upset some of the people who would be coming to the movie to see her?

“Nobody’s coming to this movie to see her,” Beatty said.

“I’m sorry?” I said, having obviously misheard him.

“I said nobody’s coming to this movie to see Hepburn.”

I stared at him, waiting for him to crack a smile but quickly realized he was dead serious. I replayed the past few months in my mind, wondering what the exigency of getting Katharine Hepburn into this movie had been about if it wasn’t somehow to raise interest in the film. Suddenly I understood that this entire casting expedition had been little more than an exercise in vanity. “Well,” I said, “when the movie comes out in video and the distributor wants a third name on the box and the video stores shelve a copy in the ‘Katharine Hepburn’ section, some of her fans might be disappointed to hear her say that line.”

“But,” Warren asked, ending the discussion, “you think she’d say, ‘Fuck a duck?’ ”

Yes, Warren. Only one or two bits out of the pages I had brought over made their way onto the screen. And I did leave him with one further suggestion, which had to do with the moment when Warren’s and Annette’s characters say goodbye to his aunt for the last time. “Kate’s got a very theatrical wave,” I said. “Look at the end of Summertime.” I suggested that this could be a touching moment for Hepburn’s fans—“I mean, not that anybody’s going to see this movie because of her.”

Beatty proceeded to tell me that he didn’t understand why Hepburn didn’t seem to be enjoying herself in Los Angeles, regarding the trip as more of an “opportunity.” He said that the weather was certainly better than New York’s, the movie provided her with something to do, and “she’ll be working with the greatest living director in the world.” While a successful television director named Glenn Gordon Caron was nominally the man calling the shots on this picture, I knew that Beatty himself intended to direct the Hepburn scenes. And so, once again, I looked for even a suggestion of irony. “I’m sorry?” I said.

When I saw once again that this was no laughing matter, I said, “Well, it’s true, Cukor and Huston and Ford are all dead,” naming just a few of the giants with whom she had worked. “But what about Billy Wilder and Kurosawa and David Lean?”

“I mean guys who are still working,” Beatty contended.

“How about Stanley Kubrick?”

“Yeah,” he conceded, “but he hasn’t made a picture in years.” I refrained from even introducing such names as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Mike Nichols . . .

Beatty and I saw each other again on Sunday night, for dinner at Hepburn’s. Kate’s mood seemed lighter than it had all week. She had been applying a salve one of Beatty’s doctors had prescribed, and her skin had noticeably improved. Everybody was aglow with anticipation. As Warren and I left her, she called out to me, “I hope he’s paying you a lot of money.” Warren only laughed . . . all the way out the door.

On Monday shooting began. I had never seen Hepburn work on a set, and so I instinctively kept my distance during the days. To help her maintain her rhythm, I joined her almost every night for dinner, at which time I would find her in a robe with her hair in a towel. A few old friends occasionally appeared as well. Warren dropped by every night, and used me to compliment her indirectly, telling me in her presence how great her performance was. I had to leave at the end of the week for a writers’ conference, and two nights before my departure, Kate asked if I might visit her on the set. I said I would try. Warren seemed eager for me to drop by as well—to show, I felt, how regally she was being treated.

I drove to Warner Brothers the next day at noon, arriving between camera setups. Kate was in her large soundstage dressing room, where her hair and makeup teams were tending to her. She looked great—more alert and alive than she had in months. Norah was on hand, assistants catered to the star’s every whim, and the crew was hurrying to set their lights and camera, so that Miss Hepburn would not be kept waiting. But that’s not what excited her so. It was the work. “As you can see,” she said, swiveling in her makeup chair to face me, “they’re treating me all right. So you don’t have to stay.” An assistant director came in to announce that they were ready to film again, and Kate said by way of dismissing me, “We’ve got to play now.”

I saw Beatty and told him that I was leaving, that I felt my presence while she was working would make her uncomfortable. He suggested that I stand on the other side of the black curtain behind the set, where one could watch the proceedings on a television monitor. There I stood in the wings, alongside a slightly forlorn, sweet-faced, heavyset man who was also watching the screen intently, as Warren directed Hepburn in the scene. She did several takes, working off cue cards at first, then improvising a little on her own. By the third or fourth take, she seemed to be playing to the crew, and obviously winning their approval, as she brought more to the scene than was actually there.

She had a way of reading the most banal lines as though they were fraught with some meaning—sometimes by pausing a little here, speeding up a little there; and the moments full of import, she simply tossed off. She provided a slightly different reading on each take, but she always made a point of understating, avoiding the obvious. When the scene was finished, the man by my side introduced himself and thanked me for my part in getting Hepburn to Los Angeles. Then I realized I was talking to the director, who, evidently, was not allowed on the set during Hepburn’s scenes.

As I was leaving the soundstage, a posse of executives entered, wanting to get their first glimpses of Katharine Hepburn. From the sidelines, I watched Beatty escort them over and saw how she utterly charmed them—shaking each hand, laughing at their comments, thanking them for all their accommodations. She even posed for a team photograph, flinching only once, when one of the young executives put his arm around her.

That night over dinner, Warren carried on about how she had snowed “the suits.” Hepburn explained that that had been part of her job since David Selznick had brought her to Hollywood sixty years ago. When Warren raved about her ability to improvise in the scene they had done later that afternoon, I reminded him that much of the final sequence of Woman of the Year, in which Tess Harding is alone in the kitchen trying to make breakfast with some culinary props, had been improvised as well. As he left that night, Warren kissed Kate on the cheek, looked deep into her eyes, and said, “If I had only met you thirty years ago.”

After he left, Kate said to me, “Was that supposed to be a compliment?”

By the time I returned from my trip, Hepburn had finished her work on Love Affair. Beatty and company had treated her magnificently, and she was obviously pleased to have completed the job. She returned home as soon as possible, which was fortunate . . . because less than forty-eight hours later, the Northridge earthquake seriously rocked the house in which Hepburn had been staying, sending lamps and vases to the floor. The Beattys’ house atop the city, where I had first dined with them five months earlier, was destroyed.

The following September, Dominick Dunne wrote a profile of Warren Beatty for Vanity Fair, which detailed how Beatty had seduced Hepburn into appearing in his film. What struck me most in the article was a line toward the end of the piece, when Beatty was reflecting on stars and personalities and the subject turned to Howard Hughes. “What you must always remember about Howard,” Beatty said, “is that he was deaf.”

The following month I was invited to a screening of Love Affair, at which Beatty and I never quite found each other. The movie played even cornier than I had expected, and for me its only moments of relief came when Hepburn appeared on the screen. (Her participation in the film was billed as a “Special Appearance by.”) While her dialogue still didn’t add up to much—and she did, somewhat haltingly, utter the pointless “Fuck a duck” line—she looked good and made a strong impression, especially at the moment when she waves goodbye. I found it most touching, because again, instead of the obvious, waving big, she sat alone and simply looked down at her aging hands.

On my birthday that December, I received a dozen enormous crimson roses from “Warren and Annette.” Four years later, he showed up at a publication party for Lindbergh, which my brother Jeff threw. Except for the occasional chance encounter with Warren Beatty in the years between and since, I have never again seen or heard from “the movie star.”

Katharine Hepburn’s phone still rang, and scripts continued to appear at her door. A producer I had never met called me one afternoon to ask if I might use my influence in getting her to consider playing the role of Aunt March in a remake of Little Women—a film that would feature Winona Ryder in Hepburn’s former role of Jo. I said it seemed dubious because I thought she had no intention of becoming a character actress—even as she approached ninety. (“Please tell them,” Kate said, “I would never even think of competing with Edna May Oliver”—who had played Aunt March in 1932.) Instead, Hepburn trekked to Canada to star in one or two more forgettable television movies, her powers of concentration diminishing as the tremors in her head and hands increased. She continued to talk of future projects, decrying the quality of what was being written for older actors.

With each of my visits east, there came a moment of shock upon seeing her. Norah would usually try to prepare me for the changes I would find upon climbing the stairs to the living room. But Kate’s hair, still pulled back and piled high, looked whiter and wispier, her eyes grayer, and her body heavier, the result of her inability to exercise. Conversation became more difficult, what with her having less to report and her increasing difficulty remembering things. She seemed to be working hard to maintain her carriage, thrusting her jaw forward. “So noble,” I could hear Irene Selznick saying in her succinct way, “—heartbreaking.” Whenever I stood next to Kate, I was taken aback, seeing that she was several inches shorter than when I had met her. Her energy waned; she suffered from dizziness; she often seemed depressed.

The next year I found her in the Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital, checked in under Phyllis Wilbourn’s name. Norah had suggested to me that nobody really knew what the problem was, but that she was receiving a few visitors. Upon entering the large room, I heard a doctor addressing her in a peculiarly hostile tone, while a grim nurse looked on. “Nobody’s allowed in here,” the doctor said as I entered. “He is,” Kate corrected, as I went over to the chair in which she was sitting, wearing her familiar pajamas and ratty red robe. “He’s my friend.”

“What’s going on?” I asked, hoping to clear some of the obviously unpleasant air.

“They say I’m a drunk,” Kate whimpered, a tone I had never heard her emit.

“Now, nobody said that,” the doctor quickly asserted.

“Yes, you did,” Kate said. “You called me an alcoholic and said that I can’t drink again.” With that, she turned to me, her eyes watering. “You’ve known me a long time, Scott Berg,” she said. “Do you think I’m a drunk?” I said she was not a drunk, and I asked the doctor and nurse if they might leave us alone for a moment. Then I went over to give Kate a hug, and she put her arm around my waist, pressed her head into my stomach, and cried. “I don’t know why I’m here,” she said.

She wasn’t disoriented. In fact, she seemed sounder of mind than she had been in my last few visits. It was more that she didn’t know what was wrong with her, and nobody else seemed to know either. She just felt bad. I knew she was on a number of prescription drugs, and I couldn’t help thinking they were all somehow interacting, contributing to her general funk. “Look, Kate,” I said, “there’s no doubt in my mind—you don’t have a drinking problem . . . but as long as you’re taking all these pills, it seems to me you’ve got to stop drinking any alcohol. I mean, that’s what killed your friend Judy Garland . . . and Marilyn. That’s just common sense.” And common sense was still enough to trump any argument with Hepburn.

She was soon home, with some changes in her various drugs; and Kate entered that phase in old age of “good days and bad days.” Sometimes, good hours and bad hours. More often than not, Norah answered the telephone, usually in a state of agitation over some minor emergency with Miss Hepburn.

While never far from Kate’s thoughts, Phyllis Wilbourn gradually withdrew from the scene, as she required increasing amounts of bedrest and care from her team of attendants. During a visit to Fenwick in early 1995, I saw her sitting in a chair, staring out at the Sound, crying. I walked over to comfort her and asked what was wrong. “I’m just very worried,” she said. “Nothing will ever be the same.”

“Why do you say that?” I asked. “What are you worried about?”

“The abdication,” she said. “That changes everything. And he was our most handsome king.”

“Look on the bright side,” I said consolingly. “He evidently wasn’t very happy; and now he gets to spend the rest of his life with the woman he loves.” That cheered Phyllis up a little. As I held her hand, I added, “I’m sure he and Mrs. Simpson will have a long, happy life together.”

“Do you really think so?” Phyllis asked.

“I know so,” I said with enough authority to put her worries to rest.

Another weekend, I flew to Connecticut to attend the wedding of Dick Hepburn’s son Mundy (an artist who worked with glass) and Joan Levy (an artist who worked on canvas). The bride was dressed as a Druid princess, and Kate was in relatively fine form. She was a little unsure on her feet but, with the support of a cane, completely ambulatory. She looked tired but was attentive, as she selected a comfortable chair from which to watch the ceremony. At one point, she noticed a man across the room snapping photographs of her and asked me to stand directly in front of her, with my back to the camera, so that I would obstruct his view. Driving back to Fenwick, I asked what had been the purpose of the bride’s costume. “To prove she’s insane enough to marry into this family,” she replied.

In April 1995 Joan Levy called to tell me that Phyllis had died in New York City. I called Kate not only to offer my condolences but to find out how she was taking the loss. “What did she die of?” I asked.

“What’s the difference?” Kate said. “She stopped breathing, and she’s dead. And that’s that.”

Kate maintained her brave front until May eleventh. On what would have been Phyllis’s ninety-second birthday, a few Hepburns and some intimate friends celebrated her long life of loving companionship by burying her ashes in a cemetery in West Hartford, alongside other Hepburns. During the brief ceremony at the grave—as rain came down—Kate suddenly dropped to her knees and sobbed. I never heard her raise Phyllis’s name again.

In late winter of 1996, Hepburn was taken to Lenox Hill Hospital with pneumonia. Reports on the radio and television were fatalistic. My phone calls to the house and to her brother Dr. Bob were more encouraging. Within a few days, in fact, Kate had asked for an ambulance to take her from the hospital to Fenwick, where oxygen tanks, a hospital bed, and round-the-clock nurses were waiting. Meantime, The National Enquirer splattered a ghoulish picture of her across its cover, quoting her as saying, “Don’t be sad—I’m going to join Spencer. . . .”

Hepburn pulled through, as she would after a few other small bouts that year. But each attack compromised her vitality; and each siege brought out an army of tabloid reporters, who camped at the end of the Hepburn driveway—on “deathwatch.” The crafty ones got hold of the telephone number inside the house and tried to wrest any information from whoever answered the phone.

My visits became increasingly quiet, as Kate’s ability to converse continued to diminish. She seemed to understand what was being said, but she seemed to lack the strength to respond. Direct questions seldom elicited more than a few words, which sometimes seemed to be in response to something that had been asked earlier . . . or unasked at all. Unless there was a third person present, these encounters became difficult, for they basically demanded that the guest engage in a monologue. During one of my trips that year, I found Tony Harvey. We sat on either side of Kate all afternoon and chatted, which she followed as though observing a tennis match. After a while, however, Tony and I noticed that her attention had shifted to a box of Edelweiss chocolate I had brought from California. One by one, she took every piece of chocolate out of the box, and then, one by one, put every piece back. Tony and I kept talking, though he raised an eyebrow and looked heavenward.

In 1997, Joan Levy called me in Los Angeles to say that Kate had suddenly taken a turn for the worse and that she was sinking fast. Again I called Kate’s brother Bob, who said that this, in fact, looked like the end and that there seemed little for anybody to do. Kate had become very weak, wasn’t eating, and her “systems were shutting down.” I said I could catch a plane out later that day to come say goodbye, but Bob advised against it. “At this point, I’m not sure you’ll make it in time,” he said. “And even if you do, I’m not sure what you’ll find.”

I found Kate the next morning, in her bedroom—sitting in a chair, in a fresh pair of pajamas, a shawl around her shoulders—looking old but fine. “Do you know who I am?” I asked, as I entered the room, sunshine pouring through every window. “No,” she said, the light in her eyes. As I stepped out of the shadow of the entry and closer to where she sat, she looked up and into my face, and a big tear rolled down her left cheek. One of the nurses leaned toward me and whispered, “When she heard you were coming today, she asked me to put some lipstick on her.”

“What’s all this business about you dying?” I asked.

“I’m not,” she said, in what was clearly an effort. Then she looked a little ashamed that she was evidently incapacitated, a state belied by the animation in her eyes.

I spent the day in Fenwick, mostly in the company of the household staff, the nurses, and, later, Cynthia McFadden, who had been visiting regularly. After our morning meeting, Kate napped. Like the doctors, everyone was puzzled by Hepburn’s condition—what ailed her and how she kept springing back. They worried because she had not eaten much in days.

When she awoke, Cynthia and the others, knowing that I had to return to Los Angeles, suggested that I go upstairs and spend some time alone with her. The general consensus in the house was that she had pulled through this bout, but the end was surely close. Again, I found her sitting upright in her chair, with a tray of untouched food.

I sat by her side and asked if she wanted to eat. Like a child, she turned her head away and said nothing. I told her that I was so happy to see her but that I hated to find her this way. She sat stock-still and seemed to look through me. Winding into what I thought might very well be my last goodbye, I told her how much her friendship had meant to me over the years but how I hoped it would continue. She still looked away, now into the blazing fire. “Look, Kate,” I said leaning in very close to her and talking in a low voice, “you and I have talked about death a lot . . . and I know you’ve always been interested in the Hemlock Society and all those books on how to kill yourself. And maybe that’s where you are now. And if there’s anything I can do to help you . . . well, actually, if you’re ready to go now, the best thing you can do is just keep up what you’re doing. Don’t eat. Starve yourself. Just don’t eat.”

Suddenly her head snapped in my direction, and her eyes burned into mine. With her right hand she grabbed mine and put it on her left forearm. “I’m not weak,” she said, shaking her flexed arm for me to feel. It was unbelievably firm. “I’m not dying,” she said. “I’m strong.”

“Well,” I said, “you really do feel strong. But you don’t seem to be able to pick up a fork. And people are worried that you’re not eating, even when they try to feed you. And you can’t stay strong unless you eat. And I’m saying if you’re not eating because you’re ready to go, well then, don’t eat—”

Without having to search for words, she continued to look me in the eyes . . . and then, without making any other move, she simply opened her mouth. For the next few minutes, I fed her soup, macaroni and cheese, and coffee ice cream, which had melted, until she emptied the plate and two bowls. As she ate, I talked about how she had to start building herself up. I discussed yoga with her, and told her how Alice Roosevelt Longworth practiced postures and stood on her head into her nineties. “Can’t,” she said. I explained that anybody could, that there was always a movement of some part of the body, to say nothing of the breathing, that one could practice. I demonstrated a few basic exercises.

By the time she had finished eating, I realized I had to leave, in order to catch my plane home. I hugged her goodbye, and she held her cheek pressed against mine, then looked into my eyes until hers began to tear again. I said I would try to get back soon, but it might not be for a few months. As I started for the door, she spoke the longest sentence I had heard from her that day. “Are you still loved?” she asked.

I assured her that I was, that my longtime relationship had never been more fulfilling. “Good,” she said, then added, “I’ve been loved too.” I knew she was speaking of Spencer Tracy, but I couldn’t resist adding, “By more people than you know.”

Downstairs, everyone was anxious to know how I had found her. “She’s not going anywhere,” I said. “We’re all going to die. I mean, none of us knows how long we’re going to stick around. But I know this, she’s not going anywhere, at least for a while.”

“What did she say?” Cynthia asked. Realizing the conversation might have been personal, she stopped herself from pressing and said it was all right if I didn’t want to share what had gone on. I reported the headlines, that she had eaten her entire lunch . . . and that until then, I had thought she wanted to die. But now, I reiterated, “She’s not going anywhere.”

During the next year, I completed, published, and promoted my biography of Lindbergh—a book that I probably wouldn’t have been able to write had Kate not written to Anne Morrow Lindbergh on my behalf a decade earlier. My visits to Fenwick dwindled in number, but we communicated through family members and staff. The reports were always gloomier than what I would find in reality. Her mind wandered; but it seemed to me that she was just going on short voyages in her memory, maybe her imagination. More unusual, I thought, was what happened to her face.

Now each time I saw her, I thought of a short story by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” in which a man was born old and progressively youthened, until he died an infant. As Hepburn’s immobility increased, her physiognomy uncreased. Treatments for her skin left her visage taut and pink; her eyes seemed bigger and more expressive, lighting up at small things—positively childlike. She smiled a lot.

In the middle of May 1999—just days after her ninety-second birthday—I found myself in New York with a few free hours in which to drive to Fenwick for lunch. Kate’s courtly friend David Eichler—himself in his late eighties, and looking a good decade younger—was up from Philadelphia; and Kate’s sister Peg happened to visit that day as well, having driven down from Canton Center with a young Irishwoman, who brought a guitar. After a lunch of hot dogs with honey mustard and the standard macaroni and cheese, the girl pulled her chair right up to Kate’s and began to play and sing. Kate gazed into her eyes through the entire song, as if in a daze. As soon as the tune was finished, her eyes widened, and she said, “Great. Another.” The young woman obliged. After another encore, she and Peg left, while David and I commented to Kate on the beauty of the girl’s voice. She seemed not to know what we were talking about; and David said to me sotto voce, “Her short-term memory’s completely gone.”

He left us alone for a while, during which time I carried on what passed in those days for conversation, a gentle soliloquy, which could occasionally draw a few syllables or sounds of response. When I at last announced that I had to leave, she said, “Is that wise?” I said I wasn’t sure about that. And so she asked, “Is that necessary?” I said it was.

On my way out, I decided to drop in on Dick Hepburn, whose own declining health had kept him bedridden—sometimes asleep, I was told, as much as twenty-three hours a day. His nurse at the other end of the house told me that I was in luck, that he had just awakened.

I rapped on his door and found him in red pajamas, sitting upright on the side of his bed, motionless and staring into space. I entered, making polite conversation . . . until he said, “Present yourself.” I assumed that meant that I should stand before him. As I did, he held out his hand and said, “It is a pleasure to see you, Mr. Berg. Thank you for calling on me.” Then he lay down . . . and before I had left the room, he was sound asleep, snoring.

Ten days later I was able to steal away to Fenwick for another afternoon, where I had the pleasure again of seeing Peg, who had traveled this week with her granddaughter Fiona—a poetic soul who had been diagnosed with cystic fibrosis for more than a decade and had already outlived all medical expectations by years. She was there—carrying a portable oxygen tank—with her husband and beautiful child and talking hopefully of getting a lung transplant. Peg’s great friend Don Smith, a music teacher and choirmaster, was visiting as well, as was Dr. Bob Hepburn. Over hot dogs and macaroni, the conversation was largely about the recent shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. Peg had plenty to say about guns (too many unenforced laws against) and child-rearing (not enough parents taking responsibility for). Somehow, this swirl of subjects triggered a nostalgic twist in the conversation, a rarity in any Hepburn house.

While Kate’s mind seemed to wander, Bob and Peg told stories of their parents and their childhoods. Then Peg spoke of giving the government a sample of her blood, because the remains of some soldiers had recently been found in Southeast Asia, possibly including those of her son Tom, who had been missing in action for almost three decades. Finally the conversation turned to the other Tom—Peg, Bob, and Kate’s oldest brother. For several minutes they mused in the most matter-of-fact tones about the circumstances of his death in the twenties. I looked over at Kate, who had turned away from us and stared instead toward the fire, her face wet with tears. I grabbed a tissue and blotted her eyes.

After the other guests left, I sat alone with Kate for a few minutes and commented on the stories that had surfaced that afternoon—the sickness, the shooting, the deaths. I wasn’t expecting her to respond; I was just filling the silence. Then she spoke. “Life,” she said quietly and with some difficulty, as though it were hard to unclench her teeth, “. . . not easy.” One of Kate’s caretakers entered the room and announced that it was time for some exercise. “We go out to play, don’t we?” she said. Kate smiled broadly and said, “We do.”

Kate had said to me literally dozens of times over the years that she didn’t fear death—“the big sleep,” she called it. It was dying she was afraid of. As I looked at her that day, I realized she no longer had anything to fear. She had survived the great race without much suffering; she had come through relatively unscathed. Of course, her life, like everybody else’s, had had its share of disappointments and even tragedies. But she had approached the finish line free of most of the indignities of old age. Her days were blurring from one to another, but into her tenth decade, she was well-cared-for and comfortable—with few pains and with every need met. Loving people surrounded her.

After more than ninety years of challenges—personal, professional, emotional, and physical—Kate was surrendering, and seemed happy doing so. “Life’s tough for everybody,” I heard her say more than once, “and that’s why most people become its victims.” She lived most of her life as a contestant in that great struggle, always pushing herself hard, riding the wave and sometimes swimming ahead of it. “The natural law is to settle,” she once said. “I broke that law.”

Because Hepburn lived so long, for so many years ahead of her time, most of her fans forgot or failed to realize that she broke other “laws” in her lifetime as well. The biggest was that she refused to live as a “woman” in what was very much a man’s world. She conducted her acting career as any freelance actor might, seldom seeking the protection of a studio or manager or agent. She conducted her personal relationships with that same independent spirit. Her initial response to any interdiction was always, “Says who? Just watch.” In so doing, she became a hero, someone men and women of all ages had to admire.

At the end of the Esquire interview I had conducted when we had first met in 1983, I asked Hepburn why she thought she had endured professionally, indeed flourished, for so long while all those around her lasted only a few years or decades at best. It was one of the few questions that ever made her pause before answering. After a few seconds, she said, “Horsepower.”

When I showed her my finished, and ultimately unpublished, piece, with her interview bracketed by my commentary, I provided my own answer to the question, with which she took issue. I wrote that “Katharine Hepburn inspires because she speaks directly to the heart in a most intelligent manner. The reason for her staying power is that for the last half century, she—above all—has provided a treasury of images which represent timeless human values: courage, independence, truth, idealism, and love. She is romance.”

“Christ,” Kate argued. “I’m not romance. That’s Marilyn.”