Supporting and Working

with Parents

Too little supervision or moral panic? Can parents be helped to take a middle path?

We are living in an era when parents have intense fears about safety if their children roam around outside, yet they are often pleased or relieved that they are absorbed and quiet indoors, ‘where I know where they are’. Yet those same children are accessing the Internet unsupervised or playing computer games that are not intended for their age group, or talking to unknown people anywhere on Earth.

Parents might be:

•unwilling to address online safety, feeling they know less than their child about the digital world

•suffering from a lack of time to take children to places to play outside

•convinced their children can’t go out to play unsupervised

•living where it is not safe for their child to walk to school alone but allowing them to roam the global Internet unsupervised.

While this gaping hole in parental awareness of online risk needs to be understood and addressed by schools, the other extreme – delusional public panic or DPP – is blinding many to what is needed. Every now and then we see a huge moral panic about the dangers of too much screen time, the content children might see and a whole deluge of media horror headlines. These might be about screen time affecting children’s brains or a specific social networking site as parents campaign to have it closed down because it is linked with a tragic case. But closing down one site simply means the kids will go to another to communicate. It does not of itself educate children. What it can do is give publicity to the site. After the panics about Ask.fm in the summer of 2013, their user numbers soared as children and teens flocked to see what it was all about. It was only when the site was acquired by new owners more than a year later that they committed to setting up new moderation and safety measures.

Professor Tanya Byron, who led an independent review on this issue, has argued that ‘moral panic’ about the Internet among middle-class parents is stunting children’s development. She believes that ‘unless parents let their children explore and make mistakes – both in the real-world and online – they will never become “digitally responsible”’.69 However, she added that ‘managing these risks, and guiding children through them, is ultimately the responsibility of the adults in their lives, both at home and school. 70

The challenge is to equip parents with the knowledge they need when many primary teachers are not confident about this themselves and parents are not always willing or able to attend e-safety evenings. Thinking about how we might engage parents, it seems that DPPs should be avoided, even though it is tempting to invite parents in while a DPP is raging in the media. Instead we should aim for an incremental programme that develops with the age and stage of the child and supports a pupil’s entire school career. Starting with some facts about what we know of parents’ views might be helpful in constructing a programme to suit their needs.

There are a number of paradoxes:

•Games are seen as violent, but few parents look at ratings. Few parents look at PEGI ratings on games they buy their children, yet many are worried about the level of violence in some games. Some parents even play unsuitable games with young children.

•Parents fear inappropriate searches but there is low take-up of parental controls. Some parents are aware of what their child might encounter online. In a survey of 2000 UK parents of 7–14-year-olds by Bullguard in 2014, 36 per cent of parents said they think their child gets together with friends and searches for inappropriate terms or images, and 18 per cent put the source of this content largely down to children ‘simply Googling things they don’t understand’. But Ofcom has found that take-up of the new parental controls that could prevent this, and which parents are offered when signing up to a new provider, are incredibly low.

•Parents shop online with children using credit cards but set few rules about safe shopping. Children tell us of how they shop with a parent – often managing the process or helping, other times using the credit card themselves to purchase items or book tickets. Too often a child proudly tells me he has memorised his mum’s credit card pin or security code and asks if I would like a demonstration! One ten-year-old boy explained how he and his dad run a mini business on eBay, buying and selling games together. He is involved at all levels.

So parents are shopping online with even their youngest children, but not always teaching them how to do this safely. This can have unintended consequences as Kaspersky Lab and B2B found: One in five families said they had lost money or important information thanks to their kids’ online activity. What is more their report shows that:

44% of respondents believe their children know little about computer technology and 35% thought their kids know nothing of cyberthreats. That same lack of awareness poses risks for parents who allow their children to use their online devices. 12% of respondents said their children had accidentally deleted important information, while 6% faced unexpected bills from app stores after the youngsters got online. All in all, every fifth polled parent confessed they had had an experience of losing money or important data because of their children’s actions … [But] just 32% are concerned that their children may spend money online without parental consent, and only 27% are worried that their kids share confidential information too freely online.71

Schools want to develop partnerships with parents to help keep all children safe. But they need figures like these to engage parents. It is difficult in some schools to get parents to come in for a dedicated e-safety session. Those who work with computers all day at work, or shop and get their evening entertainment on a tablet, can feel they know it all already, while those who are not very confident online may not want to be shown up in front of others, so they stay away. So the trick is to make these messages engaging and supportive – sprinkling them into other events when parents are in school, and into the messages that are sent home.

It helps to have:

•a dedicated web page of e-safety advice on your school website

•a series of Frequently Asked Questions for parents

•a series of group emails sent out every fortnight, each with one bright idea on it

•a handout for parents

•trained local secondary pupils giving practical demonstrations to parents

•a coding demonstration by primary pupils followed by a quiz for parents (see page 190)

•up-to-date figures on parents’ use of parental controls (see Ofcom’s website for regular reports)

•prizes and challenges for pupils, with prize-giving events for parents

•well-informed governors.

Some of the tools in this section can be used at parents’ evenings or in guides sent home to parents. What has worked successfully in primary schools are sessions in which trained secondary pupils from a local or partner school are on hand to work one to one with parents and show them what primary school pupils are likely to be doing online and some safety steps parents can take. This requires a bank of computers or tablets – so that everyone can have a practical demonstration on screen.

Further below is a quiz you might use as a warm-up exercise if parents have come into school, perhaps for a prize-giving to pupils who have done some exceptional work helping others to be safe online or using the Internet for social good.

The issue of children accessing pornography

In 2005, research by the London School of Economics suggested that more than half of children and young people had intentionally or accidentally come into contact with pornography online.72 The age group looked at was aged 9–19. Around ten years later, after a wave of new devices, the end of dial-up and the arrival of ‘always on’ broadband and wi-fi, and unlimited data packages, it was forecast that far more children would be exposed to pornography online. At the same time, pop music videos and even billboard advertising and talent shows on TV are all far more explicit than would have been acceptable ten years ago. The figure is therefore likely to be much higher now due to increasing ownership of Internet-enabled devices by young people.

In Britain, people were alerted to the problem when in 2008 the Byron Review Safer Children in a Digital World 73 highlighted the following fact:‘The Internet has undoubtedly made it easier to distribute, obtain and for children to come across pornography either accidentally or on purpose.’ This seminal review concluded, ‘There is a small but accumulating body of evidence showing a link between exposure to sexually explicit material and negative beliefs and attitudes.’ Two years later, Professor Byron’s 2010 update report74 found that parents’ ‘top digital concern is easy access to pornography and inappropriate adult content’. In 2008 the Cybersurvey showed that large numbers of children and young people could get round blocks set up to prevent them visiting adult sites. Some even said, ‘I don’t have to cos my brother can.’

In the same year as the Byron update, the Papadopoulos Review looked at The Sexualisation of Young People,75 confirming the view that viewing pornography could be detrimental to the development of many young people. This idea of the ‘pornification of society’ was further explored in the Bailey Review76 a year later, pointing out the way adult material and age-restricted material was easily accessed by young people on the Internet and via video on-demand services.

This led to an agreement between the UK’s major Internet service providers and the government to offer parents a choice of whether they wanted adult content to be automatically streamed into their homes or to be automatically filtered at source. The take-up has been remarkably poor.

But what about the children? Have they gone to hell in a handcart? Not really! After a worrying period in which exposure to pornography revealed itself in unrealistic expectations of relationships, how girls should look and early sexual awareness, it seems that the kids are beginning to calm things down a little. Teenage pregnancy rates and drug taking is down, and surveys show that, despite the media focus on selfies and some explicit cases leading to high-profile suicides, every single one a dreadful tragedy for families and those working to keep children safe, in fact the percentage of teens who have been pressured into sending a nude or explicit selfie is very low – around 4 per cent. The percentage of those who have been blackmailed as a result is even lower, and the percentage of teens trying to get around blocks or filters is down. (I have been measuring this annually since 2008.)

This relief despite a relentless tsunami of sexualised imagery shows in a more clued-up teen population, better school-based e-safety education and possibly more parents having ‘the talk’ with their children. In general, there is an overall trend of risky behaviours like unprotected sex, smoking, drug use and alcohol consumption reducing among teens. Maybe their e-safety behaviour is part of this trend?

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds

The EU Kids Online research programme points out that children of less educated parents are often left alone when dealing with the Internet. Children in some families use media more intensively than others and their socialisation is dominated by media. ‘Furthermore, their parents use more restrictive measures to influence their children’s Internet use instead of trying to actively support and facilitate a safe and profitable way of dealing with media.’77

In particular, children who grow up in socially disadvantaged families often find it difficult to take advantage of the opportunities offered by media or to cope adequately with the risks that they might encounter while using them. Therefore every societal stakeholder needs to develop approaches that enable all citizens to use media for actively participating in society.78

So the EU Kids Online research shows a need to support children who have parents with a lower secondary education or less, children whose parents do not use the Internet and children who use the Internet less than once per week.

These children tend to encounter slightly fewer online risks than their peers in Europe, but they are more upset if they experience them. Furthermore, their online skills are noticeably below the European average. This is illustrated by the following findings that compare children from households with lower, medium, and higher socio-economic status, which has been defined on the basis of parents’ formal education. Children from families with lower socio-economic status use the Internet slightly less and more often not at home than children from higher socio-economic groups.79 Furthermore, they also have significantly less access to the Internet through mobile devices and their parents tend to use less active mediation strategies. However, in terms of their age when they first used the Internet and in relation to the average time spent online, there is hardly any difference between children and adolescents in low, medium and high SES families.80

Keeping parents informed and involved

‘Different childhoods?’ quiz for parents

This quiz is a light-hearted attempt to get parents to think about the lives their children lead. The answers are based on a variety of sources and are not intended to represent a scientific or definitive analysis.

•How much less do children play outside than their mums and dads did?

•What percentage of children get their entertainment from a screen compared to the percentage in the 1980s?

•How many parents think their child gets together with friends and searches for inappropriate terms or images?

•How many parents put this largely down to children simply Googling things they don’t understand?

•How many parents believe their children know little about computer technology?

•How many believe their kids know nothing of cyberthreats?

•What percentage had lost money or important information due to their kids’ online activity?

•What percentage said their children had accidentally deleted important information?

•What percentage faced unexpected bills from app stores after the youngsters got online?

•What percentage worry that their children may spend money online without consent?

•What percentage are worried that their kids share confidential information too freely online?

•What percentage personally control how their children use devices?

•What percentage had asked their Internet provider to block access to certain sites?

•What percentage of parents regularly remind their children about the dangers of the Internet?

•What percentage opted to befriend their children on social networks?

•What percentage of parents use specialised software to regulate their children’s activities online?

•How many parents are aware of the new offers of parental controls from broadband/wi-fi providers?

‘Different childhoods?’ quiz answers

•Children in 2014 play outside two-thirds less than their mums and dads did in the 1980s.

•36 per cent of children get their entertainment from a screen compared to 8 per cent in the 1980s.

•36 per cent of parents also said they think their child gets together with friends and searches for inappropriate terms or images.

•18 per cent put this down largely to children simply Googling things they don’t understand.

•44 per cent of respondents believe their children know little about computer technology.

•35 per cent believe their kids know nothing of cyberthreats.

•21 per cent had lost money or important information due to their kids’ online activity.

•12 per cent said their children had accidentally deleted important information.

•6 per cent faced unexpected bills from app stores after the youngsters got online.

•32 per cent are concerned that their children may spend money online without parental consent.

•27 per cent are worried that their kids share confidential information too freely online.

•39 per cent personally control how their children use devices.

•13 per cent asked their Internet provider to block access to certain sites.

•38 per cent of parents regularly remind their children about the dangers of the Internet.

•19 per cent opted to befriend their children on social networks.

•Only 23 per cent of parents use specialised software to regulate their children’s activities online.

•14 per cent check who their children are friends with on SNS.

When offered parental controls at sign-up with phone and broadband providers, parents are reluctant. In 2013, the government asked providers to offer an opt-out filtering system at sign-up, but an Ofcom report81 shows that only 5 per cent of new BT customers signed up, 8 per cent opted in for Sky and 4 per cent for Virgin Media. TalkTalk rolled out a parental-control system two years earlier and has had much better take-up of its offering, with 36 per cent of customers signing up for it.82

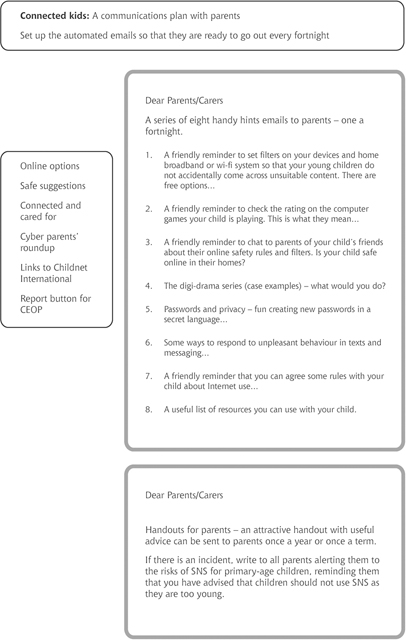

A schedule of emails to parents

Pre-prepare a series of engaging short emails which will automatically go to parents once a fortnight. Make them attractive and easily recognised. Give them a recognisable ‘brand’ that includes your school’s name, for example ‘Dreamstime School ENews’. Then archive them on the school’s website where parents can access them later. These might include ideas such as those below, for example a regular digi-drama twice a term. Use a fictional or old case and discuss what parents should do – the case could vary each time. There should be no identifying details – anonymity is vital. Below is an example.

Example of a digi-drama

Tallulah is distraught that her best friend Emma has become friends with Keisha and is now leaving her out. But the last straw came when Emma, who knew Tallulah’s password on Facebook, had been into her account and sent some mean messages to other girls in the class to isolate her further. Emma simply laughed when Talullah asked her if she was the one who did this. Tallulah is convinced it was her. But she feels anxious and suspicious of other people in her class too. Now she cannot concentrate for worrying about who it was. Emma has never apologised.

What should her parents do?

•Go round to Emma’s house and give her a piece of their mind?

•Start shouting at Emma’s parents in the supermarket?

•Tell Tallulah to forget about Emma and make some new friends?

•Keep the evidence and note the date and times the messages were sent and ask to see Tallulah’s teacher?

•Reconsider allowing under-13s onto Facebook?

•Demand the school deals with it and leave it to them?

Privacy and passwords

The following can be used to engage with parents.

Your child has used this password – his middle name and the numbers ‘123’ – since he first went on to Moshi Monsters. It was easy to remember and lots of his friends did the same. Now he is a little older he is going onto new sites and services. What advice would you give him?

Parental controls

These are a few scenarios in which parents frequently forget to re-set parental controls:

•You have just switched to a new service for your phone and broadband/wi-fi in the hope that this will be a cheaper service. About this time your child gets a mobile phone.

•You buy a tablet for your family and sign up to a new broadband/wi-fi provider.

•You bring back from work a used laptop that you have managed to buy for very little. You plan to give it to your children to use for their schoolwork and entertainment.

•Everyone is very excited at the faster speeds, the fact that you can now download movies and watch TV programmes so easily on the tablet with such a great clear picture.

What do you need to do about making sure the child or children are protected from unwanted content?

What are young children doing online?

Entertainment and games and photos

Young children love watching favourite TV characters in stories online, on tablets and mobile phones as well as on TV screens. Peppa Pig or Thomas are found on all these devices along with new characters like the Octonauts. Even three-year-olds love taking photos with a mobile. If a parent takes a shot or video of them, they understand that they can view it on the phone and often ask to see it before the phone is put down. They also know that they can ask to see it over and over again.

Games and apps that appear to be free

Small children, especially around seven or eight years old, enjoy games and might easily fall victim to games that appear at first to be free, but then pressure players to acquire ‘boosters’ to go faster or to buy special items – for a virtual pet, for example. There could be hidden costs, and heavy marketing to children can entice them to buy items for their game. They will play happily for hours on games on their mum’s smartphone. Indeed one little lad of two even sat stock still having his hair cut the other day simply because his mum gave him the phone with a game open on the screen!

Is the filter set on this phone to protect them from mistakenly clicking onto the ‘wrong’ sites?

Social clubs and groups

Children may enjoy a club or a social networking site for children; Moshi Monsters is popular, as is Club Penguin. Complaints made about Moshi Monsters, however, point out that these ‘monsters’ are drawn like disfigured faces and children with facial abnormalities or impairments are often deeply distressed at being called the names of the monsters. Some argue that this is encouraging children to bully children with facial problems or disabilities. This could be deeply distressing to a child with any form of disability or facial difference.

Google Hangouts are popular with some groups of friends, but nobody will go on any networking site without their friends, and children tend to migrate to sites simply because their friends are moving there and it is the fashion of the moment. Some begin and quickly become bored with Hangouts.

Young children enjoy searching the net for homework and projects, or to find out about a favourite footballer or pop star. They may inadvertently come across violent or sexual content and parents should set parental controls and filters to try to prevent this happening. But no filter is entirely reliable and parents should talk to their children and make it clear that if they see something upsetting they should move away and tell an adult. Explain that the world of the Internet has good people and bad people in it just like the real world and sometimes people are nasty. We should enjoy it, but be careful just the same. Innocent searches may call up surprising content, so do not blame the child if they come across inappropriate material while doing homework on the Victorians or Easter hot cross buns!

What are juniors doing online?

At ages 10–11 many children in the UK acquire a mobile phone. They may also have a games console. Both could have access to the Internet. Parental controls/filters should be set wherever available. These may be supplied by a parent’s search engine, your phone provider or anti-virus software. Software programs can also be purchased separately.

Although parents like to feel that if their child is going to school alone now they can stay in contact through the phone, there has been a marked switch to tablets with a drop in phone ownership, as families have opted for one family tablet for use by everyone rather than buying a smartphone for a pre-teen child.

They might chat with friends on instant messaging services, BBM or apps like Whatsapp or Instagram; or upload photos to share using Pinterest, Vine or Tumblr. They love making videos and posting them on YouTube. Their games now involve other players who might be online and unknown to them. They may start shopping online with a parent from time to time and could use the Internet to find out information about a holiday destination, their football club or events.

They get their entertainment, music and often films online and are adept at downloading a new game or music. Few understand that it is not right to download some music or films, for example, that appear to be free.

Their searches for information are now wider and more sophisticated. They use the Internet for homework far more and share with their friends in a new, exciting online world. They may use Twitter and many go onto Facebook before the age of 13, which is the intended barrier age, but many simply give a different birth date when signing up. Others memorise the password of their brother or sister and simply use their account.

At this age we see chain letters circulating, threats and name-calling. Bullying from school life can be amplified by going on phones or online after school and retaliating or ramping up the insults.

Get in first and talk to the child about what he or she would do if they received a nasty message or people were talking about them behind their back. Children who are prepared can become very resilient. As one boy said, ‘It was just death threats – I ignored them.’ It is both worrying that this is going on and must be investigated, and it also useful that he feels he can disregard it. Nevertheless, if the sender of the threat is in the school, some serious work needs to be done. Credible threats of harm should be considered for referral to the police. If banter of this kind is common in the school, it must be addressed with the whole class.

•Keep evidence, including the date and time.

•Do not reply or tackle the parents of the other child.

•Tell an adult who can talk to the staff at the school or sports club, who can:

°try to get the offensive material removed either by the perpetrator or the website concerned

°contact the police if this is needed

°contact the phone provider

°block the sender

°address the behaviour and try to get the perpetrator to understand the harm they have caused and help the pupils to find new ways of living alongside one another

°consider effective approaches to bullying and restorative actions that might be appropriate

°put a buddy group around the target

°teach the whole class or group that this behaviour is wrong and how to report it

°monitor how the targeted child is doing over the following weeks to ensure there is no retaliation for having reported it

°increase the teaching on e-safety and responsible behaviour online and on mobiles

°reinforce the school’s anti-bullying policy and their Acceptable Use of ICT policy

°ensure the school or club can do some work with the whole year group to challenge any prejudice-driven behaviour

°reinforce the school’s aim for every pupil to feel safe and respected

°praise people for prosocial, positive behaviour and model it.

Activity for a parents’ evening

Ask parents to turn to their neighbours and discuss the reasons they think parents gave for not having made use of parental controls. Then give them this list and ask them to discuss it. Do they recognise themselves? What next steps are they planning?

Reasons parents did not make use of parental controls83

The following reasons were given

•the idea that they are complex to install

•not understood

•lapsed and out of date

•new device bought and not re-installed

•risks not a major worry for parent right now

•not got around to it

•more inclined to worry their child spent too long online or gaming than risk

•lack of awareness

•rules not strictly followed – busy life – path of least resistance

•forgetting to install if parental controls stopped working for some reason

•thinking you have to know a lot to choose or research it

•feel ill equipped to intervene due to own lack of digital competence

•child learns about this at school

•child is always supervised

•trust child to be sensible.

Help parents to develop clear and simple rules for young children with supportive messages

The following can be used to engage with children.

•No means no: Do not be forced into doing things you do not want to do by friends or people you meet online. The Cybersurvey showed that there are many coercive threats sent around among ten-year-olds.

•Your body is your own: A doctor or a nurse may ask you if they can look at your body to help fix it, but apart from parents and people who care for you like a childminder, or a grandma, a child can say no to unwanted touching or photos. The NSPCC’s ‘Talk PANTS’ activity is useful here (www.nspcc.org.uk/preventing-abuse/keeping-children-safe/underwear-rule).

•Tell someone about secrets that upset you: Good secrets are when you plan to make a cake for your mum’s birthday and give her a surprise. Bad secrets are when someone asks you to ‘keep our little secret’ and it is about something that makes you feel sad, scared or worried. You will not get into trouble if you tell us about something you are worried about.

•Don’t say cruel, nasty things to other people whether online or off: Sometimes it is so easy to say horrible things to someone, especially if we are feeling angry ourselves.

•Speak up so someone can help: If you ever feel worried, sad or frightened you should talk to a grown-up you trust.

•If I cannot help: I can find someone who can or I can find out how to help.

•You will not get into trouble if you come to me with a problem.

•Life is full of exciting things to do and see: Most of the time it is all OK, but sometimes if things go wrong or we make a mistake, we need some help. This is OK.

Parents tell us that they turn to their child’s school as a first point of call for advice. Be ready for this with factsheets and advice that have been carefully edited and prepared. Below is an example of advice to parents about social networking sites.

Action parents can take if their child uses social networking sites

Primary schools advise parents to discourage their children from going onto SNS while under 13. Yet we know that 39 per cent of 10–11-year-olds and 72 per cent of 12–13-year-olds are doing so.84

Forbidding the child to have a social networking page will work for a while with a very obedient, compliant child, but sooner or later the pull of the peer group will lead them to want to try it out, for they fear being left out of every social interaction their friends are sharing. They might also fear that others will talk about them behind their back and desperately want to view what is going on! In some situations a child may be bullied because he or she has not got an SNS page and is therefore shut out of the group. Children and young people appear to believe that life is not truly lived unless reported online, complete with photos to prove it. It is as though it were not fully experienced unless it is shared, rather like a living diary that is put in front of readers for their ongoing approval. Of course, if that approval is sought and instead they get offensive remarks and cruel put-downs, it can hurt. They tend to know this but go for it all the same. Online they create a persona they want to project, pink and fluffy or tough and cool, but in all cases they want to appear and be popular.

Where they have been totally forbidden to go onto a social network we often see that they do so with another name so that their parents do not find out. Some even set up two profiles, one in their real name that parents can view, and another that they actually use. In situations like this a child cannot or will not seek help from their parents if they get into difficulty for fear of their parents’ reaction.

But if parents can talk through the situation in a reasonable way and encourage their child to wait until they are old enough then a good deal may be struck. Parents can also discuss this with parents of their child’s friends and together as a group they might delay the age at which the children begin to use SNS. Many are digitally capable of using social networks but are certainly not emotionally old enough.

Once they are using SNS, parents can do the following:

•Clean their friends list on SNS: Help the child to remove anyone they do not know in the offline world – having 4000 friends is not a sign of true popularity!

•Check photos are correctly tagged and privacy settings are all in place including old photos put up ages ago: Talk to the child about inappropriate images that will still be out there years from now. While everyone posts photos that they believe show them as humorous, popular and attractive, every photo should be thought about carefully before posting online. What does it say about the child? How could it be viewed? How could it be misused? What is it giving away about their identity? Do photos give away too much about them such as which school or club they go to and where the photo was taken? Is the location feature switched off on the mobile phone they use to take photos?

•Encourage them to avoid sites that offer anonymity: e.g. Tumblr or Ask.fm.

•Remind them that they can always leave a chat room.

•Talk through why they should never agree to meet anyone they have only met online.

•Make clear that you are not judgemental; they can tell you anything: For this to be true, you will have had to show an open mind beforehand. Young people can be blackmailed over something they have done, such as once posting a sexy photo, because they are scared their parents will find out. It is surely better to have made a mistake and to learn from it and be safe than to be forced into inappropriate behaviour over the initial mistake through fear.

If they are vulnerable or isolated in the offline world, young people often seek intimacy and relationships online. These young people need extra e-safety advice and support.

If a young person is being bullied face to face in school, the addition of cyberbullying sets up a devastating environment in which there is no respite. Bullying can occur multiple times a day, and targeted young people need immediate support and intervention.

•Keep a copy of the abusive messages or images.

•Record the date and time – there will be a trail.

•Block the sender where possible. Don’t reply.

•Get friends to post supportive messages and ‘drown’ out the negative messages.

•Don’t give out personal details. Report abuse.

•ChildLine and Samaritans can be contacted in multiple ways. They are trained to help.

Figure 10.1 outlines the different ways schools can communicate with parents

Figure 10.1 Connected kids: A communications plan with parents

Advice you can give the parents

•Start the conversation early.

•Little and often! Don’t overwhelm them with advice or scare them off the Internet.

•Set your parental controls on every device.

•Reassure your child you are always there to help and support them.

•Explain what to do if your child ever feels unsafe or uncomfortable in any online situation. Explain that you will not be angry; you will help because you want your child to be safe.

•Give information in small chunks rather than a whole lot at once.

•Judge when you think your child is ready for it by asking what they are doing online. Join in games, help with searches and chat about what they are finding online. If you do not understand, ask them to show you.

•Do not ban them from accessing the Internet on a mobile phone – they will have many other opportunities to access the Internet and it would be better if they did so with your advice and support. Remember, if your child uses a mobile phone with parental controls set, there will be other children in their class who use phones that do not have controls set.

•Ask questions such as:

°What do you enjoy most about being online?

°Which are your favourite games?

°How do you prefer to keep in touch with your friends?

°Can you show me how this works?

°Which websites would you recommend to a friend?

°Who do you play games with? Are they good at these games?

°How do you know whether the people in your friends list are all people you actually know?

°How would you take someone off that list if you needed to?

°Please show me how to set the privacy settings on Facebook or any other SNS.

°If we are going to buy that with my credit card, how do we know that this website is safe and it is secure to use my card?

°Do you know how to block someone?

°Can you teach your little brother what he should be careful about?

°You are so fast at this. How did you learn about it?

°What would you do if you were worried about something?

°What would you do if someone was nasty to you?

If your child knows more than you do about being online, remember you may know about life. Together you are a strong combination! Your parenting skills are needed as never before! Use your child’s expertise to get them to show you around the net, their life and their games, so that you have a better idea of what controls to put in place.

Children show parents what to do

Children enjoy showing their parents what they know and can do, and it gives parents a way to support and encourage them while learning what they know. Here are a few ideas teachers might want to suggest to parents, to encourage them towards working with their child online and opening the way to having conversations about staying safe.

Build confidence and self-esteem along with digital skills!

Enjoy the excitement and ease of the Internet together to find things out. Explore things that relate to the family holiday or the next family day out. Your child can feel he or she is making a contribution to family life, planning for a holiday or outing, or being trusted to do a task like find a translation of some key phrase or how much the currency is worth.

Show them how to use timetables, maps and distance planners. Try converting sterling to euros before you go on holiday. Google it and options to do this free of charge appear. Plan your route to the park on Google Maps. Use your phone to follow the route and teach map reading.

Children can help each other and share what they know with your guidance

You can follow up with questions like:

•Where did you learn these steps?

•Do you enjoy this site/game? What is so special about it?

•What would you do if you were worried about anything?

Children can help you set up a profile on one of their favourite websites. This will give you the opportunity to ask lots of questions like ‘What does that mean?’ or ‘Why did you choose that option?’ or ‘What if…?’ You will have an opportunity to ask about safety features and this will reveal what your child knows about them.

Children can play a game with you online

Playing together will help you understand how the game works, if it’s appropriate for their age and how they can communicate with other players. Games have ratings which parents often ignore, but they are there to help you select games suitable for your child’s age and stage. Called PEGI ratings, they give you a guide rather like the ratings for movies.

Know who your child is talking to online – they could be people somewhere across the globe

Children don’t think of people they’ve met online through social networking and online games as strangers; they are just online friends. They may even feel an obligation towards them if they play games with them online – rather like a team player. Have them show you how it all works.

Explore together where the reporting button is on the sites they spend time on. Even though there is a watershed age of 13, we know that many children below 13 want nothing more than to have their own page and profile. They lie about their age and go onto Facebook before moving on to other SNS and messaging services. They may even use your birthdate! I have met parents who say their child shares their Facebook page.

Show them how to report abuse when they are old enough to do so. Explain that social networking sites have some rules about how people behave when using their service, and if someone sends abusive messages, the material could be removed by the site if it breaks these rules.

Questions to ask:

•Who do you know that has the most online friends?

•How can they know so many people?

•How do they choose who to become friends with online?

•Why is it a good idea to have so many friends?

•Can you think of reasons why it could be risky to have friends you do not really know?

You can also become ‘friends’ with your child so you can see their profile and posts. But your child may not want to have you as a friend on social networking sites, especially as they get older, but it may be that you agree that they can choose a trusted adult like an aunt or uncle, or an older sister who can feed back any worrying or upsetting behaviour and keep an eye on the child’s social networking page.

Agreements

Agreements matter – they provide secure boundaries. Make an agreement about how they will use any new technology or spend time on the Internet. The agreement could cover issues such as:

•the amount of time they can spend online

•the websites they can visit or services/apps they can use

•sharing images and videos

•spending money online

•how to behave online respectfully and not to post anything they wouldn’t say face to face

•the age rating of all games they play and movies or TV programmes they view

•how much information they are sharing with other players

•how often this agreement will be reviewed! This might be every birthday or every time a new device comes into the household.

It should not appear restrictive and limiting – but should be presented as an enabling way for a child to enjoy the exciting opportunities the net can offer. Think of it as a licence – like a driving licence – that gives the child permission to drive and enjoy new experiences.

The following is addressed to parents.

No tool is 100 per cent effective and should not replace conversations with your child, but filters and controls are an important infrastructure step in protecting your child. Think of it as the scaffolding on which you hang your love, advice and support.

Parents can filter, restrict, monitor or report content using parental controls:

•Internet service providers (ISPs), such as Virgin Media, TalkTalk, Sky and BT, provide controls to help you filter or restrict content.

•Laptops, phones, tablets, games consoles and other devices that connect to the Internet will have settings to activate parental controls.

•Software packages are available – some are free – to help you filter, restrict or monitor what your child can see online.

Remember that if your child goes online away from home, the same controls might not be in place at other people’s houses or on public wi-fi. New ‘Friendly WiFi’ provision in public spaces with controls to make it family friendly began in autumn 2014. Look out for the sign in coffee shops and shopping centres. Many high street names have become Friendly WiFi accredited. These can be identified by the Friendly WiFi logo. This will reassure consumers that the most worrying Internet content for children, including pornography, will have been placed behind filters. This could be useful for schools when on field trips with pupils using tablets or mobiles.

When your child is visiting friends’ homes, let their parents know your rules and views on Internet use.

Which parental control system should I use?

Parental controls are reviewed by PC Advisor to help parents make their own choices. Many are free with other protection software or broadband/wi-fi provision. If you are unsure you might wish to read the reviews.

Know what connects to the Internet and how. We live in an age when connectivity is changing fast. Soon, even our houses will be wired up and we will be able to give them commands before we get home. But for now we are concerned with how your child can access the Internet. Make sure you’re aware which devices your child uses can connect to the Internet, such as their phone, a tablet, laptop or games console. Do they watch TV content on a tablet or laptop too? Also, find out how they are accessing the Internet – is it your connection, or are they often using a neighbour’s or public wi-fi? This will affect whether the safety settings and parental controls you set are being applied.

‘Safety mode’ is an opt-in setting that helps screen out potentially objectionable content that you may prefer not to see or don’t want others in your family to stumble across while enjoying YouTube. You can think of this as a parental control setting for YouTube.

In the UK customers are automatically offered parental controls when signing up for broadband/wi-fi. This is an opt-out service – it is provided as standard unless customers choose not to use it. Paid-for parental controls may offer more features.

If parents want to report inappropriate material or behaviour online they can find advice at Childnet International (www.childnet.com/resources/how-to-make-a-report). All online child sexual exploitation should be reported to CEOP (www.ceop.police.uk/Ceop-Report).

Do filters work?

Filters are only successful up to a point – their systems are as crude or as good as the dictionary of terms they will exclude. They cannot tell whether every search will be safe as some graphic material could be on a safe website, so it is not effective to rely only on filters. They also often block valid content, which might be useful for health advice or something entirely innocent or informative.

When adults relax because they ‘leave it all to the filter’, or block so much in fear, children and young people could be denied the chance to develop resilience to risk with adult help. It is also far more tempting for teenagers to try to get round this restriction and go online somewhere else – in a friend’s house, a friend’s filter-free smartphone or via some open wi-fi. Relying entirely on blocking can hamper learning, and even with the filters there will be sudden unexplained images that the filter missed. So, while parents should set appropriate filters, especially if they have young children at home, on its own this is not enough. Filtering will of course not stop cyberbullying from taking place: this is a behaviour, and the social networking sites or messaging apps are only the communication tools. Block one and bullies will use another. Children are in any case migrating to new sites all the time. It is more productive to teach civil behaviour and what to do if things go wrong.

The handout that follows has some checklists for parents set out by age.

Parent Handout *

Checklists for parents – What should your child know?

Under-5s |

6–9-year-olds |

10–11-year-olds |

Set boundaries on how long they can spend on tablets, computers and Mum’s phone Check filters are in place Put passwords or PINs on all devices Check age ratings on games and apps and also on TV programmes they can access on mobiles or tablets Set home page on family computer to a child-friendly website like CBeebies |

Teach your children to search safely with key words Show them that not everything the search engine provides is true, accurate or appropriate Ensure they know how to get help if they need it for any reason Create a family shopping email account Create a user account for your child on a family tablet or computer with a good filter and use parental controls and tools like Google Safe Search Agree on a few popular websites, clubs or TV programmes they can visit Explore the kind of personal information and identity details they should not share |

Those agreements on use of technology need revising now as many youngsters get a smartphone or use a tablet even more widely Chain letters and threats are common at this age – pre-empt this by talking about it before it happens Show your child how to set a really strong password and don’t give them yours! Warn them about risks of theft with a fancy phone Ramp up the discussion on identity and personal details by playing detective and showing a video Introduce the idea of a digital footprint and the fact that what you post can live forever online Digital citizenship can be discussed now |

|

Help them create strong passwords they can remember Discuss with any older siblings the issue of them showing their younger siblings sites or games unsuitable for the age group Negotiate rules for the family Talk to other parents about their approach, especially when your child is going to a sleepover Do you understand age ratings on games, apps and videos and TV content? Agree rules on how long they can spend on games Turn off chat features on online games Turn off the location feature on the camera of their mobile phone if they have one They may begin to use email, messaging or Hangouts |

How do we behave towards one another? How do we avoid seeing unpleasant stuff? If something you see upsets you… Not everything online is true! Don’t believe all you see or are told SNS are for over-13s Turn off the location feature on the camera of their mobile phone if they have one Agree rules on how long they can spend on games Turn off chat features on online games |

Copyright © Adrienne Katz 2015

So should you post your adorable child’s photo online?

It’s a birthday or the first day of school and you are dying to share your child’s picture. But think for a second before giving away to the world the date of his birthday so that it’s out there attached to his name for anyone to get hold of.

Check you do not show the school uniform to all and sundry – along with your child’s preferences for princess dresses. Limit who can see each picture. Check carefully that they are seen only by close friends and encourage them not to share them without your permission. Avoid those cute toddler-in-the-bath shots – they can be misused and your child might be embarrassed in years to come when his girlfriend finds them.

It is tempting to offload your memory card onto Flickr, but please, think about it first! Lots of photos can give away where they were taken – have you switched off the location feature on your phone’s camera? If not, it is safer to delay before uploading the photos of your children on a big adventure along the beach on a sunny afternoon. This location data can tell anyone what your child looks like and where he or she is. When you do post the pictures you should be safely back at home.

Parents worry that people with ill intent could misuse their child’s image in some way, but this is the least likely outcome, although it is possible and more likely if you post nude shots of your child. One blogger found her child passed off as someone else’s child, which is weird. Employers, potential girlfriends and academic institutions may search for information on your child one day – what will a search turn up? You are inadvertently creating your child’s digital identity without her permission.

What about future developments? Face recognition software already exists and websites are mining our information for details about our preferences to sell us stuff. What might be next? You might like to post pictures that do not directly show the face. It is a fact that everything you post will hang around on the net and there may be unforeseen ripples. If you are a well-known individual be even more careful with your child’s image.

Bullying and cyberbullying – entwined and feeding off one another

Parents and teachers need to be able to recognise the signs that may indicate a child is being bullied. Bullying at school migrates to cyberspace, and in the primary years most cyberbullying is the result of something happening at school. Obvious signs are:

•cuts, bruises or aches and pains that are not adequately explained

•clothes or possessions that are damaged or lost

•the child requests extra money or starts stealing

•the child starts going to school, or returns from school, at earlier or later times

•the child uses a different route to school

•the child starts to refuse to go outside at break times, or refuses to stay at school for dinners

•the child requests to change classes, options or school

•the child is not with his or her usual friends

•the child is reluctant to attend school or refuses to.

Any marked change in a child’s behaviour may indicate that the child is under stress:

•immature behaviour (e.g. reverts to thumb-sucking or tantrums)

•the child may become withdrawn, clingy, moody, aggressive, uncooperative or non-communicative

•school performance and ability deteriorate

•sleep or appetite problems or other issues such as bed-wetting

•obsessive checking of mobile phone or SNS/messaging service

•avoids playing an online game they used to love

•spends an excessive time using a webcam in their bedroom and is secretive about this.

Early signs that a child is being bullied could be:

•the child becoming withdrawn

•a deterioration in the child’s work

•erratic attendance or spurious illness

•persistently arriving late at school

•general unhappiness or anxiety

•the child wanting to remain with adults

•sudden outbursts not consistent with the child’s normal behaviour

•usual friends not seen around the child.

Physical symptoms could include headaches, stomach aches, fainting, fits, vomiting or hyperventilation. Victims can become depressed or anxious and this can continue into their adult lives.

In extreme cases a young person may express feelings of hopelessness, suggest life is not worth living, or state they are ‘hanging by a thread’. They may insist it is not worth doing anything about the bullying. Be alert to self-harm or suicidal intentions.

Patterns of thinking

Some victims of bullying begin to believe that they ‘deserve it’. They can internalise what people are saying about them and come to think that there really is something wrong with them or that they are at fault, fat, ugly or unlovable. This view must be picked up immediately and the child supported. Nobody deserves to be bullied.

Victims turn to the net to retaliate

If you were a small or shy person being bullied by another or others who seem to be all powerful, how tempting it would be to go online and, with a cloak of anonymity, send some threats to your tormentors. This is so common, but it leads victims into new problems as they almost always get discovered. They are then at greater risk.

Victims turn to the net for new friends

Another pattern is when a young victim feels isolated and friendless. She might look online for new friends – and make herself more vulnerable to grooming. If someone says ‘You are lovely’or ‘I love you’, she will agree to meet up and is suggestible in so many ways as she is eager to please.