Sherwood Point Lighthouse at dusk

Sherwood Point Lighthouse at dusk

Lighthouses. No symbol is more synonymous with our rich maritime traditions than the lighthouse. These historic beacons conjure myriad thoughts of a bygone era: romance, loneliness, dependability, dedicated keepers manning the lights, eerie tales of haunted structures and ghosts of past keepers, mariners of yesteryear anxiously hoping to make safe haven around rocky shorelines. If these sentinels could talk, imagine the tales they would tell of ferocious storms taking their toll on vessels and people alike.

A lighthouse, however, is much more than just a monument keeping ships away from shoals, reefs, islands, and other obstacles. These lights are figures of security and safety, a friend in the storm. They are identified with heroism, loyalty, danger, duty, and people caring for people. Sailors know the lights as welcoming beacons calling them home. Indeed, history documents many a weary mariner peering through the darkness, searching for a light to guide him to safe harbor. Lighthouses are a reflection of the human spirit and a mirror to our past.

The world’s oldest permanent manmade lighthouse dates to the third century BC, when Alexander the Great was king of Macedonia and Sostratos, a Greek architect, designed the Pharos of Alexandria in Egypt. Shaped like a pyramid, it was considered one of the original Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Located on an island at the entrance to the Alexandria harbor and standing more than four hundred feet tall, it claimed the title of the tallest of all known lighthouses. At dusk its keepers lit a brilliant fire, backed by a large mirror, at the top of the gigantic tower. The Pharos served seagoing people for more than fifteen hundred years before an earthquake toppled it. So important was this ancient light that the word lighthouse in several languages is derived from the word Pharos.

During the reign of the Roman Empire, at least thirty lighthouses were built along shores from the Black Sea to the Atlantic Ocean. Little information is known about some of these lights. Open wood fires probably fueled many of them.

The oldest active lighthouse on the planet is the Roman-built light at La Coruna, which dates to the fourth century AD. Also known as the Tower of Hercules, this beacon was located near the border of today’s Portugal, along the northwest coast of Spain. The Romans also built prominent lighthouses on the high cliffs of Boulogne, France, and Dover, England. The lighthouses were only eighty feet tall but stood almost four hundred feet above sea level.

In 1696 English engineer Henry Winstanley began constructing a lighthouse at Eddystone Reef near the port of Plymouth in the English Channel. Eddystone, its rocky shores bombarded by wind and waves, was considered to be the most hazardous of reefs. The first enclosed structure to house a lantern was installed here. On November 26, 1703, after the lighthouse had been in service for five years, its light was shining at midnight just as a great storm began to rage. Trees were uprooted and homes demolished. By morning the lighthouse was gone; all that remained were the broken metal rods used to secure it to the rocks. Winstanley had once said he hoped to be in the lighthouse during “the greatest storm that ever was,” and history records that he got his wish. He perished in his lighthouse during the tempest.

America is a leader in its number of lighthouses, with many hundreds guarding its shores. No other country has as elaborate a lighthouse system as that in the United States. It has even been said that lighthouses are to America what castles are to Europe.

Lighthouse Terminology

Catwalk—an elevated, narrow walkway constructed of wood or metal, raised above a pier or breakwater to allow safe access to a lighthouse in inclement weather.

Catwalk at the Sturgeon Bay Ship Canal North Pierhead Light

Daymarker—the daytime markings on a lighthouse or other aid to navigation. Historical lights were daymarked by the shape or color of the tower. Modern lights use color-coded patterns.

Eclipsing light—a light with an interval of darkness between appearances of light; frequently used when there are multiple unequal periods of light and dark emitted from a beacon.

Fixed light—a light showing continuously and steadily.

Flashing light—a beacon that gives short bursts of light.

Focal length—the distance from the center of the light source to the surface of a lens.

Focal plane—the vertical distance from the focal point of the lens to the water surface.

Foghorn, fog signal—a horn sounded in foggy conditions to give warning.

GPS—Global Positioning System; a satellite-based navigation system with worldwide coverage providing precise navigation and position.

Iso (Isophase) light—a rhythmic light with equal light and dark periods.

Lamp—the physical structure that produces the light.

Lantern or lantern room—the area in a lighthouse where the light source and lens are housed.

Lens—a device for focusing or directing rays of light.

Nautical mile (nm)—also known as a sea mile; equal to approximately 6,078 feet or approximately 1.15 statute miles.

Occulting light—a light whose total duration of light is longer than the total duration of darkness and whose intervals of darkness are of equal duration.

Parapet—a low wall or railing outside the lantern room platform used as a guardrail; also known as the gallery or the widow’s walk.

Range lights—a system involving two lights, usually one taller than the other, with one aligned in front of the other, that allows the mariner to arrange them vertically one over the other (known as getting “on range”). This allows the sailor to safely follow a straight-line course into a harbor or through a dangerous channel.

Ventilator ball—the ball-shaped exterior top of the lantern, with many small holes that enable the combustibles to be released from the burning light inside.

Winter light—a battery-powered beacon located outside the regular lantern room and used during the off-shipping season.

The first lighthouse established in North America was at Boston in the autumn of 1716, in the colony of Massachusetts on Little Brewster Island. Boston Light used whale oil as fuel, and a cannon served as the first fog warning device there. The British damaged Boston Light extensively during the American Revolution, and it was rebuilt in 1783. Boston Light has the distinction of being the lone remaining light in the United States that still has a full-time keeper’s presence, due to its historic importance. Today the US Coast Guard maintains the light. Other notable US lights include the oldest still-standing operational beacon at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, built in 1764, and the tallest US light at Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, which towers 191 feet above the Atlantic Ocean. It survived a move farther inland in 1999 to protect it from an eroding shoreline.

The year 1782 saw the first lighthouse on the Great Lakes at Fort Niagara, New York, on Lake Ontario. By the middle 1800s more than two hundred lighthouses dotted the shores of these interior lakes. Eventually more than three hundred lighthouses illuminated the way on the Great Lakes, one of the highest concentrations of beacons anywhere in the world. Along some Great Lakes shorelines there are few distinguishing landmarks, and lights were necessary pathfinders for mariners. They also illuminate harbor entrances and dangerous passageways, reefs, and shoals.

LIGHT-house, n. tower with a navigational beacon

Stripped to its essential elements, the basic components of a lighthouse include a tower, a watch room, a lantern, a lamp, and usually a dwelling of some sort, either attached or nearby. A ventilator ball tops the light. Other miscellaneous structures, such as fuel storage houses, an outhouse (often called a privy), a fog signal, and a boathouse might also be nearby.

Some of the earliest lighthouses were simple structures built of stone or wood. One of the major disadvantages of a wood structure, of course, was its susceptibility to fire. Stone towers, on the other hand, were fireproof and often could be built with locally available material. These rocky monuments had to be massive at their foundations to support the immense weight of the tower.

In the 1800s different lighthouse styles began to emerge. The most widely used design was a keeper’s home with the lantern constructed either on the roof or in a tower that was part of the dwelling. Another type, the pier light, generally was smaller, more compact, and less substantial than the standard tower and light keeper’s quarters. Pier lights were designed simply and were built inexpensively at the end of a pier, with the keeper’s quarters typically located on shore. Pierhead lights were common from the mid-1800s onward, when many harbors were dredged and breakwaters and piers constructed. Later in the nineteenth century, when increased marine traffic made more lofty lights necessary, lighthouses began taking the form of cone-shaped brick towers connected to the living quarters by a small walled passageway. Beginning around the 1860s, freestanding steel skeletal beacons were constructed. This design lessened the stress on an attached building during high winds and storms.

The light is the heart of the lighthouse. Since the first signal fires in ancient times, the age-old ritual of lighting the lamp has taken place every evening on waterways around the world. Many different materials were used as fuel for lighthouses, including wood, coal, candles, and oils such as sperm whale, fish, colza (also known as cabbage or rapeseed oil), lard, and kerosene (mineral oil). The first lighthouse light, produced by burning wood or coal, was not very bright. Crucial improvements occurred in the 1700s with the evolution of more effective oil-burning lamps with silver-coated mirrors that magnified the light source. Of the various oils used, sperm whale oil was preferred because it remained fluid in cold weather. It was used through the 1840s, but sperm oil prices quadrupled by the 1860s due to declining sperm whale numbers, necessitating a change to more economical oils. In the mid-1860s the most common liquid illuminant in US lighthouses was lard oil. Kerosene became available in the late 1870s and not only was cheaper than whale oil but also burned more brilliantly. Kerosene originally was thought to be extremely dangerous, but its use was widespread by the 1880s. The kerosene used in lighthouses was a special blend; unlike the normal kerosene that would burn a smoky, yellow flame, this special kerosene emitted a clear, white light.

Argand oil lamp

COURTESY TOM TAG

The burning of coal and oils dirtied the air and covered the interior glass of the lantern with soot. This was minimized or overcome with the use of subsequent “cleaner” fuels, including natural gas, acetylene, and finally electricity.

Lamps held and burned liquid fuels. One of the earliest lighting systems was the Argand lamp, which produced a relatively bright light equal to seven candles. This lamp contained a round, hollow wick. Air could travel both outside and inside the wick, increasing the brightness of the flame and reducing smoke and fumes. Lamps used from one to five wicks at the center; the larger the apparatus, the more numerous the wicks. Crude reflectors were tried and improved on. In the early 1800s Captain Winslow Lewis expanded on the Argand lamp, adding a silver reflector and giving the setup a curved, parabolic shape. Typically Winslow Lewis lamps used sperm oil. While this system was relatively inexpensive, it was drastically inferior in light quality to a new shining star on the horizon: the Fresnel lens.

Augustin Jean Fresnel (pronounced fra-NELL), a French physicist born in the late eighteenth century, is credited with designing the lens that revolutionized lighthouses worldwide. Indeed, he is considered the father of the modern lighthouse optic. In 1822 Fresnel developed the compound lens that would bear his name, bringing with it a marked improvement in the effectiveness of lighthouses. The principle is still used in lens design today.

Fourth-order Fresnel lens at North Point Milwaukee Lighthouse

Fresnel lenses were built with multiple tiers of prisms around the top and bottom that gathered the light, produced parallel rays, and focused them into an extremely efficient, intense beam many times more powerful than anything before it. A shiny brass framework held the lens together. The shape of these hand-polished cut-glass lenses has been likened to a potbellied stove, a beehive, or a barrel. The Fresnel lens produced a fixed, steady light beam, unless the lens contained a center bull’s-eye or flash panel. In some lighthouses, a clockwork rotational mechanism revolved the lens at an exact speed and thus emitted a rhythmic flashing light. Often the mechanism controlled by the clock device had to be wound by hand every three to four hours—meaning some trusty keepers never got an uninterrupted night of sleep! No mechanical clockwork equipment for turning a lens is employed today. If a modern lens flashes, it is rotated by an electric motor.

Several French companies built Fresnel lenses. They included Barbier & Fenestre; Henry-Lepaute; Sautter, Lemonier & Cie; and Barbier, Benard & Turenne, among others, all located in Paris. The lenses were built in France, ferried unassembled across the Atlantic Ocean, and then erected in the lantern of the lighthouse. The workmanship of these lenses is remarkable even by today’s standards.

There were six sizes, or “orders,” of Fresnel lenses, the numbers signifying different focal lengths. The range and concentration of the light produced differed accordingly. The first three orders were the largest, had the longest range, and were used primarily for coastal lights. A first-order lens could be as tall as twelve feet and weigh three tons. Costs could approach $10,000, a lot of money in the mid-1880s. The smaller orders, four through six, were generally used as harbor lights because they had shorter ranges. A sixth-order lens would stand only a foot and a half tall and cost significantly less than the larger orders. The most common Fresnel lenses on the Great Lakes were third, fourth, fifth, and sixth order, along with a three-and-a-half-order lens in some locations, including Michigan Island in Lake Superior. Only a few Great Lakes lighthouses had large, second-order lenses, none of them in Wisconsin.

While preliminary expenses for Fresnel lenses were high, the magnification and concentration of the light beam decreased fuel costs to 25 percent of what they had previously been. The strength of the light beam expanded nearly four to five times and increased the light’s range twofold! If positioned one hundred feet above lake level, a Fresnel lens light could be seen as far as eighteen miles away. The first Fresnel lens in America was placed in 1841 at Navesink Lighthouse, New Jersey. By the end of the 1850s, almost all US lighthouses were using the French technology. Fresnel, the genius who has been called the father of the modern lighthouse, died at the young age of thirty-nine. He was not recognized for his achievements during his lifetime.

By the 1930s most of the Fresnel lenses’ old internal oil and wick lamps had been replaced with incandescent lights that increased the strength of the beam even further, from tens of thousands of candlepower to as many as several million. Today the fundamentals of the Fresnel system appear in car headlights, traffic signals, the flashing lights of emergency vehicles, and movie projector lights. The “fish-eye” mirror utilized by truck drivers and the plastic “lens” mounted on the rear window of motor homes to enhance rear-view vision use optic principles formulated by Monsieur Fresnel.

Another lighthouse lamp, first used around 1910, was the incandescent oil vapor (IOV) lamp. Much like the Coleman lantern of today, the vapor lamp employed a mantle rather than a wick, and the fuel was vaporized, producing a significantly brighter light. Incandescent electric lamps would later become the norm.

Lighthouse builders employed different types of lanterns as well. The uncommon “birdcage” style, which from a distance resembled a birdcage, was used around the mid-1800s, but the eight- to ten-sided lantern we see today was the most prevalent. Slowly, standard styles of lighthouses emerged on the Great Lakes, as several reliable designs were used repeatedly. Because of this, some of the light styles on the Great Lakes are virtual copies of one another. In Wisconsin, Sand Island, Chambers Island, and Eagle Bluff lighthouses share a comparable style. Green Island, Pottawatomie, and Old Port Washington lights have other similar design characteristics.

To supplement the lifesaving function of their lights, many lighthouses were also equipped with a fog signal. When conditions were too poor for light visibility, mariners could follow a foghorn’s mournful sound to safe harbor. If a sailor could not establish his position because the light was obstructed, he could rely on the periodic blasts of the howling foghorn. In the early 1850s mechanical fog bells and air fog whistles were used. Later, steam-powered fog whistles gave way to fog sirens. The majority of fog signals in service on the Great Lakes in the early 1900s were steam train whistles. They presented a problem, however: it took nearly an hour for one to be fully operational. In the time that elapsed, either a hapless ship was already in trouble or the fog had vanished. Gasoline-powered fog engines followed, and in the 1930s fog signals were converted to electricity and could even be powered up by remote control. No original nineteenth-century steam-driven fog signals survive today.

The dawn of the electric light in the late 1800s led to an exciting development in the efficiency of lighthouses. Electricity was first employed at a US lighthouse in 1886 to light the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. It took several decades, however, for electricity to become widespread among US lights. Other twentieth-century advances included timers that automatically turned the lamps on and off and a rotating mechanism that could replace a burned-out electric bulb. Soon after the arrival of electricity at more light stations in the 1920s, automation of the lights and fog signals followed. By the middle of the 1900s almost all Great Lakes lighthouses were electrically powered. Another advancement, radio communication, came in the 1920s, allowing the keepers to speak immediately with the ships that relied on them.

One of the initial acts and priorities of our fledging country’s first Congress dealt with lighthouses. In 1789 Congress passed the Lighthouse Act, making the US Treasury Department responsible for the building and maintenance of all light stations. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton would be the first commander of US lighthouses. The federal government now controlled the lights and dictated rules about them to the states. In the early years of our nation, the president played an active and direct role in decisions regarding lighthouses, including the hiring and firing of keepers and determining when and where new lights should be built. Indeed, many of the earliest lights in the United States were the first public works projects, as growing trade in eastern coastal areas necessitated additional lights. Financial support for aids to navigation first came from fees levied on ships entering US ports. Beginning in 1801, Congress funded lighthouses.

Succeeding Hamilton as lighthouse superintendent was Stephen Pleasonton, an able administrator, bureaucrat, and bookkeeper with no engineering or maritime background. With the official title Fifth Auditor of the Treasury Department and the Superintendent General of Lighthouses, Pleasonton ruled like a dictator for several decades (1820–1852). Hundreds of new beacons were constructed during Pleasonton’s tenure, but his miserly ways contributed to a decline in the condition of many lights. Many of Pleasonton’s decisions regarding lighthouses during this period may have been politically motivated, and some might be termed corrupt. Pleasonton had a financial stake in the Winslow Lewis lamp (see page 6) and was single-handedly responsible for the delay in instituting the technologically superior Fresnel lens system in the United States.

Many complaints arose, from mariners in particular, suggesting that the US lighthouse system needed revamping. By the middle of the 1800s, a diverse group of people including sailors, shipping merchants, and politicians advocated the switchover to the Fresnel lens. Superintendent Pleasonton continued to delay its implementation, insisting that tests and more information were needed. In 1852, responding to the demand for improved navigation aids, Congress created the US Lighthouse Board, comprising the secretary of the treasury, military officers, scientists, engineers, and government secretaries, among others. That same year saw Pleasonton finally removed from office.

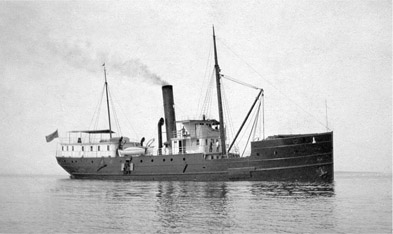

This United States Lighthouse Service vessel transported supplies to various lighthouses in Door County.

WASHINGTON ISLAND ARCHIVES

The Lighthouse Board divided the country into twelve lighthouse districts, each with an inspector; quickly made improvements to many light stations; and furnished detailed written instructions of duties to all US light keepers. The board touted the Fresnel lens as the light of choice, and by the Civil War Fresnel lenses were in use in lighthouses all over America. Mariners described the light from these lenses as blazing compared to the antiquated lamps and reflectors.

The US government published an annual “Light List” beginning in 1869. If an area possessed several lights, they would be distinguished from each other by color or by rhythms known as the light characteristic, such as the interval of time between flashes. This was known as the light’s signature. Sailors often referred to the flashing lights as those that “winked” at them in the darkness.

In 1910 the Lighthouse Board evolved into the Bureau of Lighthouses, also known as the Lighthouse Service, in the Department of Commerce. The exemplary leadership of George R. Putnam, the first commissioner of lighthouses, shaped the agency in a positive manner for decades. A phrase often used by the Lighthouse Service during these years of change was, “In the interest of economy and efficiency in administration . . . ” Putnam’s tenure saw advancements in radio technology, particularly the radio beacon; a retirement system for light keepers; and other improvements. By 1940 the Lighthouse Service employed more than five thousand people, from keepers and assistant keepers to inspectors and the staff who provided and delivered supplies.

In July 1939 President Franklin Roosevelt and congressional sanction merged the Lighthouse Service with the US Coast Guard due to the threat of war overseas, once again making administration of aids to navigation the responsibility of the military. At the same time, the government continued to improve lighthouse efficiency.

The 1940s and 1950s saw many lights being automated, and the 1960s witnessed automation in full force. Eventually the cost-effective measures of massive light automation took over the system, and the Coast Guard’s role with regard to lighthouses was reduced to providing routine maintenance. The long technological voyage of the lighthouse in the United States, starting with whale-oil lamps and wicks, gave way in most cases to fully automated, solar-powered electric lamps. Some argued that the “depersonalization” of the lights was necessary as progress marched forward. The light’s only real purpose, they argued, was safety. Others expressed the opposite opinion, contending that the passing of the faithful light keeper and the outright abandonment of many lights was an occasion not to celebrate but to mourn.

In some remote locations where it was too difficult or dangerous to erect a permanent beacon, mobile floating lights called lightships aided navigation. This was not an assignment for the weak of stomach, as light vessels contended with many a stormy sea. Even experienced sailors would sometimes become seasick. Both hazardous and lonely, lightship duty was considered one of the most dangerous assignments in the Lighthouse Service and later the Coast Guard.

The United States’ first lightship began service in 1820 in the Chesapeake Bay; the inaugural Great Lakes lightship was placed at the Straits of Mackinac at Waugoshance Shoal in 1832. Soon dozens of lightships were on duty in the United States. At least two lightships guided mariners in Wisconsin, at Peshtigo and Milwaukee. Originally constructed of wood, lightships later were made of iron or steel. These vessels often lacked propulsion of their own and would be towed to a site by another boat and anchored.

Lifesaving Stations

Foghorns, lightships, and lifesaving stations played a critical role in maritime safety. The United States Life-Saving Service, launched by Congress in 1848, positioned structures near lighthouses or harbor entrances and staffed them with volunteers to help rescue shipwreck survivors stranded close to shore. After 1871 a paid, full-time keeper and paid full-time six-man crews worked for the US Life-Saving Service, and by 1900 there were several dozen lifesaving stations on the Great Lakes outfitted with lifeboats and equipment to secure a lifeline to nearby vessels in distress. A surprising number of Wisconsin communities were home to these aids, including Kewaunee, Two Rivers, Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Plum Island, Baileys Harbor, and Sturgeon Bay in Door County. During their heyday, lifesaving stations surely lived up to their name.

Lifesaving crew, Milwaukee. WHI IMAGE ID 55832

Within the Lighthouse Service was another group of vessels known as tenders. Their job was to convey personnel, much-needed supplies and equipment, visitors, and news to many light stations. While keepers and their families looked forward to visits from the tenders and welcomed them with open arms, the tender often brought with it the lighthouse inspector. Sometimes arriving unannounced and ready to perform the “white glove test,” the inspector commanded high respect. A poor report from the inspector could mean eventual removal from the position. However, the inspector’s visit did have a positive side. Along with news of the outside world, beginning in the mid-1870s inspectors brought traveling libraries to the more remote lighthouses. A collection of approximately fifty books on subjects including poetry, science, and history, novels, contemporary magazines, prayer books, and the Bible were circulated to light keepers to lessen their boredom and loneliness.

Starting in the middle 1860s and for reasons unknown, tenders were usually named after shrubs, trees, or flowers. The Marigold frequented Lake Superior, while the Hyacinth served many lighthouses on Lake Michigan. The Sumac and Dahlia also tended lighthouses in Great Lakes waters.

Eventually most lightships and tenders outlived their original intent and usefulness and were decommissioned or sold for other nautical purposes and, inevitably, scrapped.

Lightship Milwaukee, circa 1925. In the 1850s lightship crew members were paid twenty cents a day

COURTESY US COAST GUARD

Lighthouse tender ship Dahlia, circa 1900

COURTESY CONNIE SENA

While the light was the heart of the lighthouse, the keeper was its soul. Many keepers and their families devoted an appreciable portion of their lives to these beacons. They toiled many hours of the day and night, keeping vigil over their precious lights. Since the earliest days when boats plied the waters of Wisconsin and around the globe, the central goal of the light keeper was to keep the lamp lit. Keepers endured periods of isolation, loneliness, monotony, harsh weather conditions, balky equipment, and rugged living. In some precarious locations, the keepers and their lighthouses were exposed to severe storms. With nowhere else to go, the lighthouse was the shelter the keepers themselves sought to ride out tempests. Everyday necessities we take for granted today often were lacking from light keepers’ lives. There often was no indoor plumbing, for instance, and at many stations the keeper had to carry water for personal use from the nearby body of water. If bad weather was raging, water was that much harder to obtain or was of poor quality. Many dwellings were warmed and meals cooked with only the heat of a wood or coal-burning stove.

Lighthouse keepers were stalwarts. In many ways they were ordinary, hardworking people who at times faced extraordinary circumstances. Lighthouse people were a hardy lot and for the most part took pride in discharging their duties and were thankful for a steady job with a regular income. The light stations and surrounding grounds were reflections of the keepers and their families. Put yourself in the shoes of the keeper: climbing tall towers or walking out to pier lights with fuel or equipment, winding mechanisms for flashing beacons every few hours, cleaning and polishing glass and brass endlessly, keeping the lighthouse grounds shipshape. The list of duties seems infinite.

First Assistant Keeper Charles Boshka at Pilot Island, 1898

COURTESY CONNIE SENA

Despite its rigors, the position of light keeper was highly sought after and was considered prestigious. Many of the earliest keepers were handpicked by local officials, others the result of military service, nautical experience, or political assignment. Patronage and cronyism sometimes won out over a keeper faithfully performing his duty. Because the US government was intimately involved in the management of lighthouses and their personnel, these sentinels’ role in our country’s history and politics is complex.

Cana Island spiral stairway

Lighthouse keeping was often a family endeavor, and there are abundant examples of multiple family members—fathers and sons, wives, a few daughters, brothers and uncles—joining the Lighthouse Service. Records of several generations of the same family working at the same lighthouse are common.

In the early 1850s the US Lighthouse Board found the competency of keepers to be so diverse, and in some cases so lacking, that it recommended that keepers be tested for the position. Records show some keepers who were removed from their positions when they were determined to have been performing their lighthouse duties less than adequately.

A light keeper candidate now had to be at least eighteen years of age, be literate (in the earliest days, some keepers were not), as well as be fit to do manual labor and have some mechanical or sailing aptitude. The board also began trying to limit the political appointment of keepers.

Beginning in 1896 lighthouse keepers were included in the US civil service system. The board continued to advocate for lighthouse keepers as a professional service. Many people advanced through the US Lighthouse Service, from secondary positions such as assistants to that of keeper.

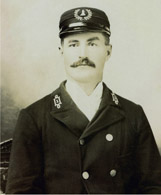

The US Lighthouse Board instituted a uniform for male light keepers in 1884, consisting of a dress uniform as well as fatigues for working. The dress uniform incorporated a coat, trousers, vest, and cap all made of dark blue flannel or jersey. In warmer climates, the cap and coat were white and were made of a lighter-weight material. Two rows of five yellow metal buttons dressed up the front of the double-breasted coat. The cloth cap had a lighthouse badge fastened immediately above the bill.

Keeper’s uniform; photo taken at Old Port Washington Light Station

MANY KEEPERS DEVOTED most of their adult lives to lighthouses. Keeper Joseph Napiezinski, a light keeper at Rawley Point, Manitowoc Breakwater Light, and other Wisconsin lights, served the US Lighthouse Service for forty-eight years.

While the US Lighthouse Service was predominantly a male organization, it was not an exclusive men’s club. Beginning in 1850 the Lighthouse Service appointed scores of female keepers and several hundred more female assistant keepers. In fact, the first women US government employees were most likely lighthouse keepers. Often the wife of the keeper became the assistant keeper; if the husband died, his wife was the logical replacement as keeper. This phenomenon was not because the Lighthouse Service was ahead of its time in the equal employment of women. It simply was budget conscious to have a husband-and-wife pair on the payroll rather than pay for two separate living quarters.

Women played significant roles both directly and indirectly in the bountiful history of many US and Wisconsin lighthouses. They learned the workings of the lights and tended them as well as their male counterparts. (They were excluded from the task of painting the light tower, however.) History holds many tales of women light keepers rescuing sailors. Without a doubt, these women were oftentimes true lighthouse heroines.

Several Wisconsin lighthouses, including beacons in the Apostle Islands, the Kenosha (Southport) Light, the Old Port Washington Light Station, North Point Milwaukee, and others, had a significant woman’s presence. Some of these women performed lighthouse duties into their seventies.

Keeper Georgia Green Stebbins, son Albert, and dog Tappan at North Point Milwaukee, circa 1888

COURTESY BUZ STEBBINS

The everyday care of the lightkeeping family was almost always the woman’s responsibility as well. As was common at the time, most children who grew up in lighthouses walked to school, no matter the weather. For children who lived at island lights, a daily boat trip back and forth to the mainland was routine. In extremely remote locations, a parent, usually the mother, took on the role of educator in addition to her other responsibilities. In some areas schooling took place after the navigation season was completed, with island-dwelling families moving to the mainland each winter.

Keepers’ salaries seem paltry by today’s standards. In the early 1800s the pay was $200 to $250 a year. In the mid-1850s Congress enacted a law setting the average annual pay at $600, and that wage remained steady for decades. In addition to wages, the keeper and family were provided a house and supplies. Most light station grounds had room for a vegetable garden and some fruit trees, and some families kept chickens and cows. It’s a good thing the keepers could provide for themselves in these small ways, because for many years they had no retirement plan. It wasn’t until 1918 that Congress passed an act allowing light keepers to retire at age sixty-five with thirty years of service and making retirement mandatory at age seventy.

Despite the small salary, a keeper’s tasks were myriad. A formal publication of the US Treasury Department, Instructions to Light-Keepers, was printed for employees who tended the lights. Some of the basic keeper’s rules in 1902 included the following:

Federal government regulations stated that a light had to be ignited thirty minutes before sunset, kept burning all night, and extinguished thirty minutes after dawn every day. There was little room for excuses when it came to having a dependable working light. The keepers ensured the light remained lit by keeping the fuel replenished and repeatedly—every few hours or so—pruning the wicks precisely to ensure a clean burn. This chore gave rise to light keepers being known as “wickies.” Keepers needed to accurately monitor oil consumption as well.

Keepers learned many of their duties on the job. If a keeper was fortunate enough to have an assistant, each person worked twelve-hour watches: noon to midnight, and midnight to noon. At night it was the keeper’s duty to make sure, if his or her light had a flashing beacon, that its timing remained uniform. The keeper periodically had to wind the machinery that turned the light and make adjustments to the timing mechanism to ensure that the light revolved at a precise speed.

Keepers cleaned and polished the lens often, in most cases daily, to remove soot and smoke buildup that might obscure the light. They also kept the chimney of the lens room open and spotless to prevent smoke from accumulating in the lantern. If the light station had a fog signal, it was the keeper’s job to keep it in good working condition as well. Fog signals required constant attention.

Another important duty was the keeping of the daily log. Most days the notation was simply a weather report or a mention of the number of ships passing the complex. On occasion, ships in distress or other significant events might punctuate the logbook’s entries.

After lights were powered by electricity, the problem of soot obscuring the lenses was eliminated. Now the keepers need not spend so much time maintaining the light. This didn’t mean, however, that they had newfound spare time. Keepers now kept busy inspecting the lenses for chips or cracks, keeping them free of dust, and changing the lightbulbs. What’s more, US Lighthouse Service and later Coast Guard regulations insisted that the whole location be flawlessly cared for—a never-ending duty, since nature had a way of taking its toll on these coastal facilities. Interiors and exteriors needed frequent painting, and brass fittings required endless polishing.

Nevertheless, with the advent of electricity, many lighthouses no longer needed personnel to routinely tend the beacons. Eventually millions of dollars would be saved by automating the lights. The manned lighthouse was slowly becoming a thing of the past. Modern improvements in radar and radio beacons, along with today’s satellite technology and Global Positioning Systems (GPS), rendered the lighthouse to a less important status. The US Coast Guard finalized automation of all United States lighthouses in 1992. The need for mortal keepers had been eliminated.

The appropriately named Great Lakes are a significant part of our heritage. Collectively Lakes Michigan, Superior, Huron, Ontario, and Erie are considered to be the “fourth seacoast” of the United States. Constituting approximately 20 percent of the world’s and 90 percent of the United States’ fresh water, they are the earth’s largest fresh surface-water source and its most expansive interior watercourse, forming a watery one-thousand-mile thoroughfare from Superior-Duluth in the west to the St. Lawrence Seaway in the east. This superhighway of yesterday was vital to the economic development of the region and of the country as a whole.

Before our elaborate modern system of railways, roads, and interstate highways, water transit was the most practical, least expensive, and most reliable method of moving goods and people. The Great Lakes helped fuel a growing nation. But progress commanded a costly price in lives and ships lost. Increased shipping traffic necessitated the construction of more lighthouses. Great Lakes lighthouses were a vital cog in the expansion of nautical trade from the mid-1800s through the early 1900s. In the years just after the Civil War, the Great Lakes teemed with vessels hauling wood, grain, and other products to expanding markets nationwide. Many of the first lights on Lake Michigan were built at the mouths of rivers because a village, town, or city was nearby. The first Lake Michigan lighthouse was constructed at the mouth of the Chicago River in 1832. By the end of the nineteenth century, ports saw thousands of arrivals and departures annually. Where wooden schooners and then steel-hulled boats once plied the waters, today one-thousand-foot supercarriers transport their cargo over the Great Lakes. The Great Lakes remain a transportation hub for America in contemporary times.

These titanic inland bodies of water, also known as sweet water seas, brew up storms that rival those of the world’s oceans. Great Lakes storms can be fierce and deadly, especially in November. A glance through historical records reveals a scattering of tragic and immense gales: November 11, 1835, “swept the lakes clear of sails”; October 15, 1880, saw Lake Michigan and Door County battle the Alpena Gale; the Great Lakes Storm of 1913 killed more than 250 sailors and damaged or sank a dozen vessels; the Armistice Day Storm of November 11, 1940, was also lethal on the lakes. In one of the most widely retold contemporary accounts, Lake Superior claimed the modern freighter the SS Edmund Fitzgerald on November 10, 1975. Approximately 3,500 ships have gone to their graves on the Great Lakes. With the Great Lakes navigation season consuming much of the calendar year (the lakes are usually open from approximately late March to early December), these tempests will continue to be a force to be reckoned with.

Lighthouses without a doubt have saved many lives on gale-ravaged Great Lakes waters. But lighthouse builders here have confronted many obstacles in constructing their lights. Building engineers had to solve problems of towering bluffs, shoals, sandy beaches, and other difficulties. Construction crews had to overcome high winds, rough seas, and dizzying heights in order to build seaworthy beacons. All told, more than three hundred beacons eventually illuminated the Great Lakes.

Wisconsin is bordered on several sides by significant waterways and is named after the Wisconsin River, which diagonally bisects it. Ouisconsin, a French version of an Ojibwe name for the river, translates to “gathering of the waters.” Located at the headwaters of both the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River systems, Wisconsin attracted European settlers and the maritime trade that became the backbone of local economies. Water-borne commerce, the thread that weaves through the entire region, was the lifeblood of early Wisconsin.

In the first half of the 1800s, approximately one-third of a million people resided in what would become the state of Wisconsin. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing were the predominant occupations of the day, and wood, ore, grain, and coal were the primary products transported over the region’s waterways. Industrial development increased dramatically in the 1850s, and in the nineteenth century Wisconsin would be a major shipbuilding center.

The growth of commerce and the increasing size of vessels on the Great Lakes led to the need for harbor development. Piers were built, harbors dredged, and aids to navigation erected. Most Wisconsin ports sported pierhead lights beginning roughly in the 1870s, and most major Wisconsin cities with a tributary stream connecting to the Great Lakes possessed a lighthouse. Wisconsin’s first light, Pottawatomie, dates to 1836; most of the state’s lighthouses began their service between 1850 and 1900.

Wisconsin became a territory in 1836 and achieved statehood in 1848. For more than 175 years, lighthouses have assisted mariners making their way through Lakes Superior and Michigan and inland Lake Winnebago. Blazing a trail through the darkness, the lights have played a tremendous role in shaping Wisconsin into the diverse state it is.

Wisconsin beacons have their own personalities and characteristics. Several are one of a kind, lone representatives of certain styles. From the westernmost reaches of Lake Superior and the northern limits of the Apostle Islands, to Lake Winnebago, to the Bay of Green Bay, to vacationland Door County and the entire length of Lake Michigan’s western shore, these beacons have innumerable tales to tell. Lighthouses are like people: every one is different. Let us attempt to capture the essence of each of Wisconsin’s lights with a photo and venture to recount a small fraction of their facts and stories.