BOTH AUTHORS have mothers in their late nineties. When one of us asks his mother about her favorite hometown sports teams, she says, “Oh, they’re up and down, up and down.” The other’s mother likes to say, “Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose.” Although we are more passionate and specific when we discuss our teams, there is something attractive about the greater patience and acceptance about the ups and downs that apparently come with older age.

American rugged individualism has had its share of ups and downs, wins and losses, since its birth at the founding of our nation and its coming of age on the frontier. We’ve sought to dramatize it a bit by asking in the title whether it is dead or alive. It’s not a purely academic question since there have been those who have sought to kill it. As Henry Kissinger said, “Even a paranoid has some real enemies.” Although it has taken some tough blows, somehow American individualism has lived to play another day. Indeed, we wonder whether the new social and business frontiers of the information age might be fruitful ground for yet another important chapter of rugged individualism.

Why should we care? Because rugged individualism is a unique component of America’s DNA, a key ingredient in what makes America “exceptional.” Underlying all the freedoms that the pioneers and founders sought to establish in the new country was individual liberty. It would be the individual, not the monarchy or the social class, who would be the essential unit of analysis and action in the New World. Herbert Hoover, who actually coined the phrase “rugged individualism” in 1928, contrasted it with the soft despotism and totalitarianism of Europe.

To place our work in the context of other writing about individualism, ours is not a book that looks at individualism primarily through the lens of psychology or sociology. Rather, we are interested in the political context in which American rugged individualism flourishes or declines. As Stephanie Walls argues in her 2015 book, Individualism in the United States: A Transformation in American Political Thought, at the founding American individualism was primarily political in nature, protected by the Constitution and fully compatible with democracy.

During the Progressive Era, however, rugged individualism became more about economics. Progressives both attacked rugged individualism directly and caricatured it as the myth of the robber barons and captains of industry. This economic critique of rugged individualism continues today through the work of French economist Thomas Piketty and others about income inequality, proposing both an economic and a political revolution in order to restore the equality of conditions that French journalist Alexis de Tocqueville found and admired in America.

Then, in the last thirty years, the battleground about rugged individualism has come to include the realm of sociology. Sociologists such as Robert Putnam and Robert Bellah worry that Americans have turned inward, staying home and disengaging from social and especially civic life. Putnam is concerned because Americans are now “bowling alone.” Their solution is both a societal and a political transformation in civic engagement to protect against the dangers of rugged individualism, which they convey as anti-communitarian.

Our view is that, while nearly everything undergoes change over time, rarely is a transformation or revolution called for, especially over something as fundamental as American rugged individualism. Whereas the Progressives seek an economic revolution and the sociologists a social one, we see more continuity with the founding, believing that an awakening to the continuing value of political individualism is needed. Therefore, we go back in order to come back. We go back to the founding and to the American frontier in order to come back to public policy today.

As we travel the road of rugged individualism from the founding to today, we note persistent efforts to detour from that path, or even to destroy it. During the period 1890–1940, the Progressives launched full frontal attacks on rugged individualism and also sought to minimize and end its influence through caricatures of it as a myth of the rich. In particular, President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal sought to replace the rugged individual with the forgotten man as the object of government policy. The rise of the New Left and also Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society posed major threats to rugged individualism in the 1960s. Today, rugged individualism faces a host of enemies, from the rise of executive power, to the advance of narratives such as income inequality or our “antiquated Constitution,” to the federal takeover of health care and education. But even rugged individualism’s enemies acknowledge its continued existence.

We look with some optimism toward new frontiers of the twenty-first century that may nourish rugged individualism. There is a new “networked individualism” in the Internet age that is placing power back in the hands of the individual. Young people, through both their social media lives and their business careers, are making their own way as individuals on new frontiers. New books and popular television programs celebrate the rugged American spirit in conquering and overcoming new challenges. Although it is not clear how this might translate to the political realm, it could be that the very awakening to American rugged individualism we call for may already be in its early stages.

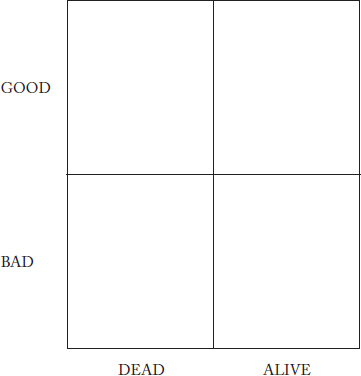

Perhaps as you read, it might help to think about where you stand on the matrix below (figure 1). Do you believe American rugged individualism is alive or dead? Whichever you find to be true, do you think that is good or bad? For example, President Barak Obama believes it is alive and well, yet he finds that to be wrong-headed and unfortunate. In the Progressive Era, historian Charles Beard thought rugged individualism was dead and that was a good development. Today Robert Putnam and Robert Bellah think it is alive and that it is a bad development for America. Your two authors think it is alive, if only barely, and want it to be strengthened. We place ourselves firmly in the upper right-hand quadrant. How about you? We trust you will find the resources in this book to help you better understand and appreciate rugged individualism.

David Davenport, Stanford, California

Gordon Lloyd, Malibu, California

Figure 1: Rugged individualism matrix

Source: David Davenport and Gordon Lloyd