CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

Turning Darkness into Light

I rushed home full of questions. But when I sat with my sisters in our living room, I found out I didn’t even understand what I didn’t understand.

“You just left an interview with one of the most accomplished women in the world, and all you can talk about is that she got hit on by her mentor?”

That was Briana. She’s three years older than me, was in her third year of law school, and for as long as I’ve known her, she’s been fighting for what she believes.

“Even during the interview,” Briana continued, “when you asked Goodall about it again, she told you it wasn’t a big deal. Her response to Leakey’s advances was everything I hope I would do if that happened to me.”

She stood up from the couch. “I think I know why you were so upset. It’s because you see a sexual advance as an act of disrespect. Sometimes it is, but it isn’t always. For my whole life, you and Dad were always like this. Dad made it clear that if a guy even showed interest in me or Talia, it was an act of aggression—which is why you got so triggered.

“And I’m surprised it took you this long to realize that women deal with these kinds of things all the time. You’ve been living with women your entire life. You grew up with two sisters, a mom, and nine girl cousins who were your best friends. I can even remember you reading I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings in high school. If anybody should have realized this stuff earlier, it should have been you.”

My gaze lowered and I stared at my feet. When I looked over to my younger sister, Talia, she was sitting there quietly, taking it all in. I knew I’d be hearing from her soon.

“I’m not trying to make you feel bad,” Briana added. “I’m just trying to make a point. If even you didn’t understand the issues women face, and you grew up surrounded by women, imagine what it’s like for guys who didn’t.”

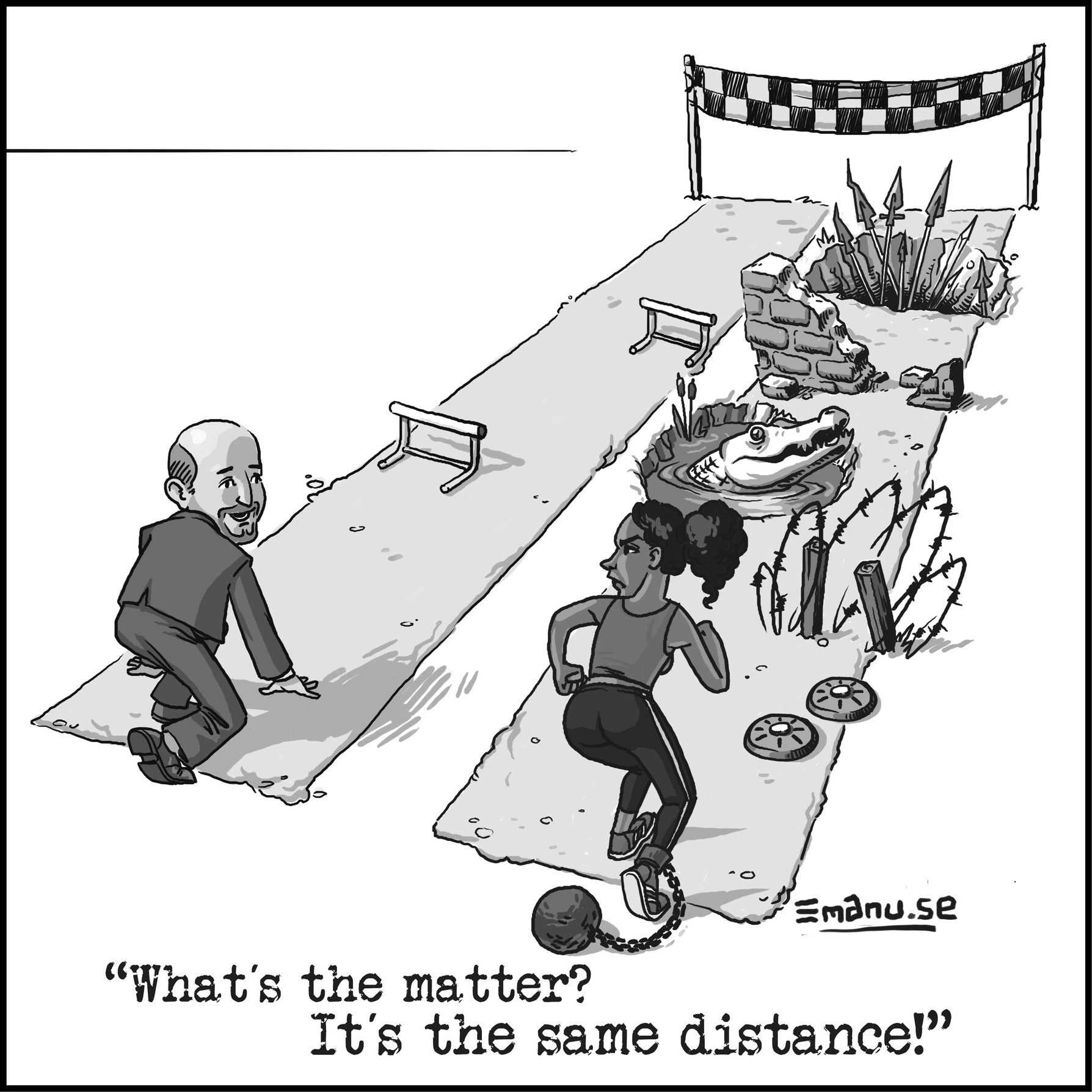

A silence settled over the living room, and then Talia took out her phone. She pulled up a meme on Facebook and put the screen in front of my face.

As I stared at the image, Talia said, “I bet you’re focusing on the wrong part. It’s not only all the extra obstacles women face that bothers me—it’s that sentence on the bottom. It’s the fact that most men won’t even acknowledge our reality. There are problems women face that most men will never understand…because they never try to understand.”

It’s hard to know for sure why I hadn’t experienced Maya Angelou’s memoir the way Briana assumed I had. When I’d read I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings as a teenager, I was so overwhelmed by the African American experience that it was all I’d focused on. Maya Angelou was born in an era when you could see a black man dangling from a tree, or look out a window and see hooded Klansmen setting fire to a cross. When Maya Angelou was three years old, she and her five-year-old brother were placed on a train car all alone headed to the South, with nothing more than a nametag tied to their feet. Angelou and her brother were received by their grandmother and taken to her home in Stamps, Arkansas, a town clearly divided between blacks and whites.

Only now, as I picked up Maya Angelou’s memoir again, did I try to see it through the lens of her gender. One afternoon, when she was eight years old, Angelou was headed to the library when a man grabbed her arm, yanked her toward him, pulled down her bloomers, and forced himself on her. He then threatened to kill her if she told anyone what had happened. When Angelou finally reported who raped her, the man was arrested. The night after his trial, he was found dead, kicked to death behind a slaughterhouse. Shaken and traumatized, Angelou internalized it as if her words caused that man to die. For the next five years, Angelou didn’t speak.

As time wore on, she faced even more obstacles. She got pregnant at sixteen, worked as a prostitute and madam, and was a victim of domestic violence. At one point, a boyfriend drove her to a romantic spot by the bay, beat her with his fists, knocked her unconscious, and kept her captive for three days. These events, though, are not what define her. What defines Maya Angelou is how she turned darkness into light.

She channeled her experiences into works of art that made waves in American culture. She became a singer, dancer, writer, poet, professor, film director, and civil rights activist, working alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. She wrote more than twenty books, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings spoke so directly to the soul of readers that Oprah Winfrey has said: “Meeting Maya on those pages was like meeting myself in full. For the first time, as a young black girl, my experience was validated.” Angelou won two Grammy Awards and was the second poet in American history, preceded only by Robert Frost, to recite a poem at a presidential inauguration.

And now I was about to pick up the phone and give her a call. A friend of mine had helped arrange the interview. Angelou was eighty-five years old and had recently been discharged from the hospital, so the interview was just fifteen minutes long. My goal was simple: not only to ask the questions my sisters had come up with, but to listen and, hopefully, understand.

My sisters boiled down their questions into four obstacles. The first was how to deal with darkness. There’s an expression Maya Angelou coined called “rainbow in the clouds.” The idea is that when everything in your life is dark and cloudy, and there’s no hope in sight, the greatest feeling is when you find a rainbow in your cloud. So I asked Angelou, “When someone is young and just starting out on their journey, and she or he needs help finding that rainbow, in mustering the courage to keep going, what advice do you have?”

“I look back,” Angelou said, her voice soothing and wise. “I like to look back at people in my family, or people I’ve known, or people I’ve simply read about. I might look back at a fictional character, someone in A Tale of Two Cities. I might look at a poet long dead. There may be a politician, could have been an athlete. I look around and realize that those were human beings—maybe they were African, maybe they were French, maybe they were Chinese, maybe they were Jewish or Muslim—I look at them and think, ‘I’m a human being. She was a human being. She overcame all of these things. And she’s still working at it. Amazing.’

“Take as much as you can from those who went before you,” she added. “Those are the rainbows in your clouds. Whether they knew your name, or would never see your face, whatever they’ve done, it’s been for you.”

I asked what someone should do when they’re searching for rainbows, but all they see are clouds.

“What I know,” she said, “is that: it’s going to be better. If it’s bad, it might get worse, but I know that it’s going to be better. And you have to know that. There’s a country song out now, which I wish I’d written, that says, ‘Every storm runs out of rain.’ I’d make a sign of that if I were you. Put that on your writing pad. No matter how dull and seemingly unpromising life is right now, it’s going to change. It’s going to be better. But you have to keep working.”

Angelou once wrote, “Nothing so frightens me as writing, but nothing so satisfies me.” When I had shared that quote with my sisters, they’d said it resonated with them. In many ways, that applies to any kind of work you love. Briana’s passion for special education law had turned into her dream, but now that dream was turning into a cold reality of applying to firms and wondering if she was good enough. I brought up that quote to Angelou and asked how she dealt with that fear.

“With a lot of prayer and much trembling,” she said, laughing. “I have to remind myself that what I do is not an easy thing. And I think that’s true when any person begins doing what he or she wants to do, and feels called to do—not just as a career, but really as a calling.

“A chef, when she or he prepares to go into the kitchen, has to remind herself that everyone in the world, who can, eats. And so preparing food is not a matter of some exoticism; everybody eats. However, to prepare it really well—when everybody eats some salt, some sugar, some meat if they can, or want to, some vegetables—the chef has to do it in a way that nobody has done it before. And so this is true when you are writing.

“You realize everyone in the world who speaks, uses words. And so you have to take a few verbs, and some adverbs, some adjectives, nouns, and pronouns, and put them all together and make them bounce. It’s not a small matter. So you commend yourself for having the courage to try it. You see?”

The third obstacle was dealing with criticism. In Angelou’s autobiography, she wrote about joining a writer’s guild. She read aloud a piece she’d written and the group ripped it apart.

“You wrote that it pushed you to acknowledge that if you wanted to write,” I said, “you had to develop a level of concentration found mostly in people awaiting execution.”

“In the next five minutes!” Angelou said, laughing again. “It’s true.”

“What advice do you have for a young person who’s dealing with criticism and looking to develop that same level of concentration?”

“Remember this,” she said. “I’d like you to write this down, please. Nathaniel Hawthorne said: Easy reading is damn hard writing. And that’s probably just as true the other way around; that is, easy writing is damn hard reading. Approach writing, approach whatever your job is, with admiration for yourself, and for those who did it before you. Become as familiar with your craft as it is possible to become.

“Now, what I do, and what I encourage young writers to do, is to go into a room alone, close the door, and read something you’ve written already. Read it aloud, so you can hear the melody of the language. Listen to the rhythm of the language. Listen to it. Before you know it, you’ll think, ‘Mmmh, it’s not too bad! That’s pretty good.’ Do it so you can admire yourself for trying. Compliment yourself for taking on such a difficult, but delicious, chore.”

Obstacle four was an issue Briana was confronting. As she looked for a job, every job description she found said, “Prior experience required.” But how could she get prior experience if all the jobs require prior experience? In Angelou’s autobiography, she faced a similar problem.

“I read when you were hired as the associate editor of the Arab Observer,” I said, “you bluffed your way into the job by inflating your skills and prior experience and, when you were hired, you had to really learn how to swim. What was that like?”

“It was hard,” Angelou said, “but I knew I could do it. That’s what you have to do. You have to know that you have certain natural skills, and that you can learn others, so you can try some things. You can try for better jobs. You can try for a higher position. And if you seem assured, somehow your assurance makes those around you feel assured. ‘Oh, here she comes, she knows what she’s doing!’ Well, the thing is that you’re going to the library late at night and cramming and planning while everybody does their thing.

“I don’t think we are born with the art,” she added. “You know, if you have a certain eye you can see depth and precision and color and all of that; if you have a certain ear, you can hear certain notes and harmonies; but almost everything is learned. So if you have a normal brain, and maybe a little abnormal, you can learn things. Trust yourself.”

I had one minute left. I asked if she had just a single piece of advice for young people as they launch their careers.

“Try to get out of the box,” she said. “Try to see that Taoism, the Chinese religion, works very well for the Chinese, so it may also work for you. Find all the wisdom that you can find. Find Confucius; find Aristotle; look at Martin Luther King; read Cesar Chávez; read. Read and say, ‘Oh, these are human beings just like me. Okay, this may not work for me, but I think I can use one portion of this.’ You see?

“Don’t narrow your life down. I’m eighty-five and I’m just getting started! Life is going to be short, no matter how long it is. You don’t have much time. Go to work.”

As time passed, I became even more grateful for this conversation, because if I’d waited much longer it wouldn’t have happened. Almost exactly a year after this phone call, Maya Angelou passed away.