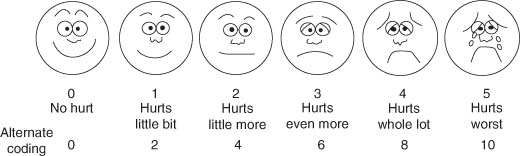

Figure 6.1 Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale [2].

Analgesic Regimens for Children

Key points

The under-treatment of pain in children has been well documented. A survey more than 20 years ago found that 40% of paediatric surgical patients experienced moderate or severe postoperative pain, and that 75% had insufficient analgesia. The fundamental reasons for this under-treatment were concerns relating to side effects from drugs given to children and misconceptions as to the nature of pain at younger ages. Since then increased interest in this area has led to a better understanding of the developmental neurobiology of pain and analgesic pharmacology and has consequently allowed for the development of safer and more effective analgesic techniques for children of all ages.

Children are not a homogeneous group of patients. Numerous factors specific to a paediatric population can influence the success of analgesic treatment. Developmental age has a profound effect on both the processing of nociceptive information and the response to analgesia. Allied to this, the pharmacology of all drugs is age and size dependent, requiring appropriate dosage adjustments. In addition, communication issues with the very young or developmentally delayed can influence the ability to assess pain and monitor the response to treatment. Thus, the effective and safe management of pain in children of all ages requires significant background knowledge on the part of their caregivers.

Pain perception

Nociceptive pathways are present from birth and even the most premature infant is born with the capacity to detect and respond to painful stimulation. During fetal, neonatal and infant life the nervous system is continually evolving. This allows structural and functional changes to occur continuously in response to the child’s needs as it grows and develops. The pain pathways mirror these changes with different components developing along differing time frames. The structural components required to perceive pain are present from early fetal life, although pathways involved in modifying pain perception are still developing during infancy. Alongside this, the expression of the many molecules and receptors involved in the pain pathways vary in their number, type and distribution between early life and adulthood.

These structural and functional changes will affect both the immediate and short-term responses to pain and analgesic effect. Conversely pain or analgesic treatment at this time may also predispose to persistent or long-term changes affecting the functioning of the somatosensory system in later life. For a more in-depth review please see Fitzgerald and Walker [1].

Designing analgesic regimens

Successful pain management is based on the formulation of a sensible analgesic plan for each individual patient. It is best to take a practical and pragmatic approach dependent on the patient, the type of surgery or illness, and the resources available. The primary aims are to: recognise pain; safely minimise moderate and severe pain; prevent pain where it is predictable; bring pain rapidly under control; continue analgesia for as long as it is required.

Analgesic plan

An analgesic plan should be devised for each individual patient. The plan will depend on a number of factors (see Table 6.1). The plan should be discussed with the patients, parents and staff to confirm acceptability, consider preferences, answer questions and take into account previous experiences. The plan should allow treatment to be titrated to effect and should also include provision for the rapid control of breakthrough pain and the identification and treatment of side effects. In established paediatric centres with a high level of resources, a dedicated paediatric pain service is the ideal standard of care. Where this is not available, significant improvements in pain management can be made by the establishment of clinical routines and protocols for the treatment and assessment of postoperative pain, and a network of interested medical and nursing staff to provide ongoing education.

Table 6.1 Designing an analgesic plan: factors to consider.

Pain assessment

Pain assessment is central to good pain management. Appropriate clinical assessment has been shown to improve both the safety and efficacy of pain management in children. It allows for the prompt administration of analgesia and is an effective method of monitoring treatment. Effective pain assessment involves regular clinical monitoring of the child by trained staff allied with the use of an appropriate pain scoring tool. Pain is subjective in nature and the use of self-reporting pain tools is generally regarded as the gold standard. However, this requires a certain degree of both cognitive and physical development. In younger, and especially nonverbal, children or those with cognitive or communication difficulties, other approaches are necessary, and tools using behavioural and physiological measures have been developed. Tools for routine clinical use should be practical, valid for the clinical setting and age range of the patients, and be acceptable to staff, patients and parents.

Self-reporting tools

Linear visual analogue scores are generally accepted as appropriate in children older than 7–8 years. ‘Child friendly’ adaptations of these scores have been designed for younger patients and have been used down to ages as low as 4 years, e.g. face-type scales (Figure 6.1), although at these younger ages the scales may not be truly linear and are not directly interchangeable or numerically comparable with other scales.

Figure 6.1 Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale [2].

Behavioural and physiological measures

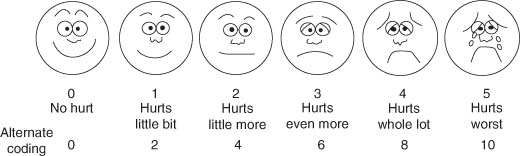

Use of pain-related behaviours is considered to be one of the most reliable indirect methods of pain assessment. Behaviours with the highest specificity and validity for pain in children across the ages include: cry, facial expression, posture of the trunk, posture of the legs, and motor restlessness. These form the basis of the many validated pain assessment scores available, e.g. the FLACC pain measurement tool (Table 6.2). However, it is important to remember that these behaviours change with age, can be affected by other factors such as hunger, distress, anxiety and concurrent drug treatment, and are open to individual interpretation by the healthcare workers using the tools. Physiological measures, e.g. heart rate and blood pressure, and hormonal responses have also been used to assess pain either on their own or in conjunction with behavioural observations, but they lack both sensitivity and specificity and this approach is of limited value.

Table 6.2 The FLACC pain management tool. Each of the five categories: Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability is scored from 0 to 2, which results in a total score between 0 and 10 [3].

Assessment in children with neurodisability

Observational pain tools are the mainstay of pain assessment in children with severe physical or cognitive impairment, although few suitable tools have been designed for and validated in this group of patients. The FLACC tool has been validated for this group, as have tools that use individual pain behaviours identified by their parents such as the Paediatric Pain Profile (PPP) and the Non-Communicating Patients Pain Checklist.

Multimodal analgesia

Paediatric analgesic regimens are usually based on the principle of multimodal or balanced analgesia. This involves the simultaneous use of a number of analgesic interventions to achieve optimal pain management. Analgesics acting independently and synchronously on pain mechanisms at different points on the pain pathway are likely to be more effective than a single drug. Using more than one analgesic will also decrease the consequences of interindividual variability in drug pharmacology. It also potentially minimises the doses of drugs used, thereby minimising side effects and possibly accelerating recovery. Multimodal analgesia also allows for the use of nonpharmacological pain control strategies such as comfort measures and psychological techniques, when possible.

Using a multimodal approach, effective pain management is achievable for most cases and the technique can be adapted for day cases, major cases, the critically ill child, or the very young. In current practice in children, most analgesic techniques are based on differing combinations of four main classes of analgesics: paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids and local anaesthetics. Unless there is a contraindication to do so, a locoregional analgesic technique should be used in all cases. For many minor and day case procedures this, in combination with paracetamol and NSAIDs, may allow opioids to be omitted.

Routes of administration

Analgesic drugs can be given by a variety of routes and the choice of route can have a significant impact on the efficacy of pain management. The choice must be acceptable to the patient, parents and staff. For example, intramuscular injection, which is unpleasant, is now relatively contraindicated despite proven clinical effectiveness. Poor compliance with this technique, as both staff and children disliked it, was a major factor that led to the early reports highlighting the undertreatment of pain in children. When possible, prescriptions should allow for more than one choice of route of administration. The routes in common use are:

| Oral: | Generally the preferred route but not always achievable. If present, a gastrostomy or jejunostomy may provide an alternative. For most commonly used analgesics, many different formulations are available in terms of flavour and liquids or tablets to allow for the varied tastes of children. |

| Rectal: | A useful and convenient alternative when the oral route is unavailable, although for some patients it may be unpleasant or unacceptable. However, the absorption of many drugs by this route is slow, erratic and unreliable. |

| Intravenous: | This allows for rapid onset and high efficacy. However, outside of the perioperative situation, use of this route may be limited by logistical and safety concerns. |

| Subcutaneous: | Allows for continuous and intermittent infusion of low volumes of drugs and it is often easier to establish access compared with intravenous injection. Provided tissue perfusion is good, absorption seems to be predictable and rapid, but the pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous analgesics in children have not been well studied. |

| Epidural: | Provides extensive and profound analgesia at the site of surgical insult with little systemic effect, and offers the option of long-term infusion. However, it requires skilled operators for placement and trained staff with adequate resources and monitoring for subsequent management. Also, in the majority of children, placement needs to be performed under general anaesthesia, and there is a failure rate associated with the equipment, especially with small epidural catheters. |

| Transdermal and transmucosal: | Lipid-soluble drugs can be rapidly absorbed in small volumes from highly vascular sites. This allows a potentially rapid onset and high efficacy without the need for painful needle access. Intranasal diamorphine has been used with success in the emergency room for painful procedures. Significant opioid-related side effects are still common. Absorption via the transdermal route is slower but newer technologies in delivery systems are improving this. Topical application of local anaesthetics is frequently used for minor painful procedures. |

| Inhalation: | Nitrous oxide and oxygen (Entonox) inhalation has been successfully used for the management of brief painful procedures in children. Acceptability is often good but trained staff with specialist equipment and a suitable environment are required. |

Analgesic drugs and techniques

Pain intensity and duration in the perioperative period are usually predictable and planning analgesic requirements is relatively straightforward. Many combinations of drugs and techniques are possible. Potent analgesic combinations are usually required initially, with a gradual reduction over time as healing occurs, and with pain finally being managed with simple, readily available analgesics. Opioids, paracetamol and NSAIDs are usually administered regularly as part of a multimodal strategy. Local anaesthesia can be used in the form of a ‘single-shot’ technique at the time of surgery or as a postoperative infusion either centrally or peripherally. Other agents such as N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) antagonists (ketamine) and α2-adrenergic agonists (clonidine) can be added to supplement the multimodal strategy and/or prolong the effect of local anaesthetics.

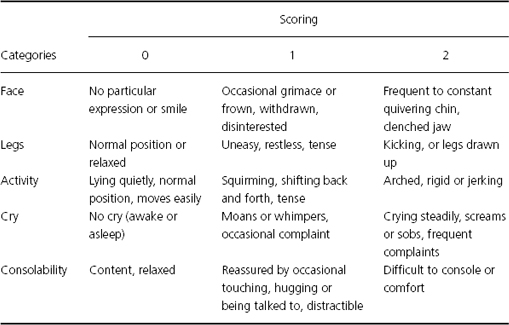

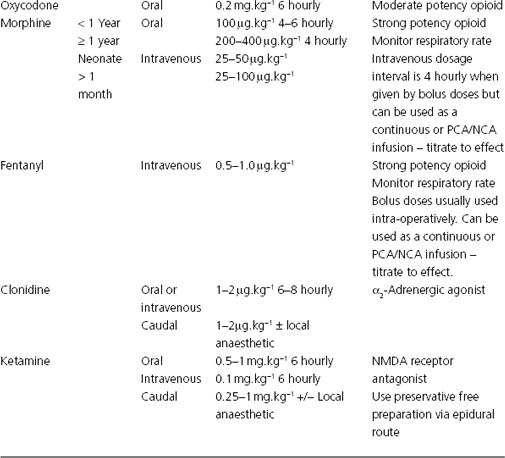

In other situations, such as pain associated with trauma, medical disease, malignancy or chronic pain syndromes, the predictability of the intensity and duration of the pain may not be clear. Whilst the analgesic drugs and techniques used in the postoperative period may also be appropriate in these situations, the analgesic regimens must be designed with sufficient range and flexibility to allow for easy administration and titration to the child’s needs. However, in some situations in which these first line analgesics are either not working or are known to have limited efficacy, other drugs with analgesic properties such as gabapentin, antidepressants or anticonvulsants may be given. Recommended doses of commonly used analgesics are given in Table 6.3.

Table 6.3 Commonly used analgesic drugs in children.

Paracetamol

Paracetamol is the most widely prescribed drug in paediatric hospitals and has become the mainstay base analgesic in almost all situations. Its analgesic potency is low and it is effective against only mild pain on its own. However, in combination with NSAIDs and weak opioids, it has been shown to be effective for moderate pain, and it demonstrates an opioid-sparing effect when used in tandem with the more potent opioids. Paracetamol has a mainly central mode of action, having both antipyretic and analgesic effects. It has been shown to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis in the hypothalamus, decrease hyperalgesia mediated by substance P, and decrease nitric oxide generation involved in spinal hyperalgesia induced by substance P or NMDA. It has also been suggested that paracetamol acts at cannabinoid receptors.

The oral bio-availability of paracetamol is very good as it is rapidly absorbed from the small bowel. Rectal absorption is slow and incomplete, except in neonates. Thus, if possible, it is preferable to give paracetamol orally or intravenously. If it is given rectally at the start of a short procedure (<1 hour), it is unlikely to reach therapeutic plasma levels by the time the child wakes in the recovery room. Intravenous paracetamol may have a higher analgesic potency than either the oral or rectal preparations, as uptake into the cerebrospinal fluid is greater and faster after intravenous administration than via the other routes. Regular rather than an ‘as required’ postoperative prescription has been shown to provide better analgesia.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

These drugs act mainly peripherally by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis and thus decreasing inflammation, although central effects have also been postulated involving the opioid, serotonin and nitric oxide pathways. They are highly efficacious in their own right in the treatment of mild to moderate pain in children. They have a reported opioid-sparing effect of 30–40% when used in combination with opioids, and also decrease the incidence of opioid-related adverse affects, as well as facilitating more rapid weaning of opioid infusions. It has also been shown that they are highly effective in combination with local or regional nerve blocks. Combination with paracetamol produces better analgesia than either drug alone.

There are limitations to their use in paediatric populations. In the UK, ibuprofen is now available in over-the-counter formulations for children aged ≥3 months, and it has been used in children aged down to 1 month in the hospital setting. At present, diclofenac and other NSAIDs are not recommended for children <6 months of age. Care should also be taken in those patients who are asthmatic, have a know aspirin or NSAID allergy, are hypovolaemic or dehydrated, renally impaired, coagulopathic or where there is a significant risk of haemorrhage. A careful history of previous use of NSAIDs should be taken in every case. Different NSAIDs have different side effect profiles and the relative risks associated with each of the contraindications will differ between drugs. In the UK, the Committee on the Safety of Medicines has classified ibuprofen and diclofenac as having the best side-effects profiles.

Bio-availability is good via both the rectal and oral routes. The onset of action is faster when given orally. Higher than expected dose requirements are seen in children if scaled by body weight from adult doses. Other routes of administration are available, such as intravenous and topical, although their use in children so far has been limited and few data are available.

Opioids

Opioids remain the mainstay of analgesic treatment for the majority of situations in which pain is moderate to severe. The choice of which opioid to use will depend on the patient’s medical history, the clinical situation, drug availability, any locally devised protocols and individual clinician preference. The pharmacology of these agents changes during early life and these changes are not consistent between different drugs. When using a particular opioid in neonates and infants, it is important to understand the pharmacology of that particular drug in those age groups to ensure both efficacy and safety.

Morphine remains the most commonly used opioid. Morphine clearance is decreased and the elimination half-life is increased in neonates when compared with infants and older children. Also, in neonates the glucuronidation pathways, the main metabolic pathways for morphine, are still developing, slowing morphine metabolism and giving a relatively increased production of morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine. These differences may to some extent account for the increased efficacy of morphine seen clinically in neonates.

Codeine, another popular opioid in neonates and infants, is metabolised to morphine. The cytochrome P450 enzyme, CYP2D6, which is responsible for this conversion, shows markedly reduced activity at these ages when compared with that seen in older children and adults. Thus, it may be that little or no morphine is produced from a dose of codeine. In addition, the CYP2D6 enzyme demonstrates genetic polymorphism, and the ability of individuals of all ages to convert codeine to morphine varies dramatically. This may explain codeine’s good safety profile in young children but may also suggest that its analgesic efficacy is often questionable.

Tramadol has a dual mode of action. It is an agonist at μ receptors but also works by enhancing descending inhibition via the serotinergic and noradrenergic systems. In children, it has been shown to be effective for mild to moderate pain, with a good safety profile. Oxycodone is similar in structure to codeine, although the analgesic effect is exerted by the parent molecule rather than its metabolites. It has also been shown to be effective for the treatment of mild to moderate pain in children.

The fentanyl family of synthetic opioids is also widely used in children. These drugs exhibit high potency and rapid onset. They are mainly used as intraoperative opioids, although fentanyl has been shown to be a useful alternative to morphine for opioid infusions in many clinical settings. These drugs also demonstrate age-dependent differences in their pharmacology and care must taken in younger age groups. However, remifentanil shows similar pharmacokinetics and haemodynamic stability across all age groups.

Opioid infusions

Opioid infusions must be given in conjunction with clear protocols for infusion rates and the detection and treatment of side-effects, educated staff, appropriate monitoring and a safe nursing environment. If all these factors are in place, opioid infusions can be effectively and safely used in even the most premature of neonate.

Continuous infusion

Morphine at infusion rates of 10–40 μg.kg−1.h−1 will manage pain effectively in most clinical situations. Continuous infusion has been shown to have greater efficacy when compared with intermittent bolus regimens. Analgesic control can be comparable with the more flexible nurse-controlled and patient-controlled analgesia techniques, but changes in rate alter plasma levels slowly in comparison with these supplemental bolus methods. Lower infusion rates should be used in neonates to take into account the altered pharmacology in this age group.

Nurse-controlled analgesia (NCA)

This approach increases the flexibility of a continuous infusion by combining a moderate background infusion with the ability to give two or three extra demand-led boluses per hour. Reliable pain assessment has been shown to improve efficacy.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA)

In children, a small background infusion (4 μg.kg−1.h−1) has been shown to improve night-time sleep patterns without increasing the incidence of side effects. Aside from this, traditional adult PCA settings are used. With the right supervision and monitoring, PCA can be used in children as young as 5 years.

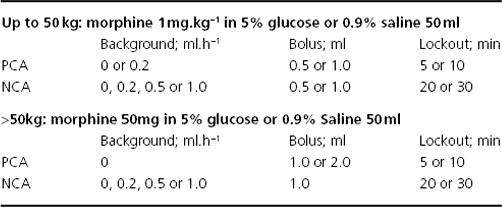

Suggested NCA and PCA infusion protocols are shown in Table 6.4. Opioid-related side effects such as nausea and vomiting, itching, sedation and respiratory depression can occur in a dose-dependent fashion. Sedation scoring and monitoring of the respiratory rate should be performed in all patients receiving an opioid infusion. Oxygen and opioid antagonists must be readily accessible in case of emergency, and anti-emetic and antipruritic drugs should be available if required. The subcutaneous route remains an alternative to intravenous administration but it should not be used in hypovolaemic patients.

Table 6.4 Nurse-controlled (NCA) and patient-controlled (PCA) analgesia infusion Protocols (Great Ormond Street Hospital Pain Control Service).

Local anaesthetics

A local anaesthetic technique of some sort is appropriate for nearly all surgical procedures and forms an important component of a balanced analgesic technique. It allows site-specific analgesia, demonstrates a lack of sedative and respiratory side effects and decreases systemic analgesic requirements. For children in other clinical settings, nerve blockade may also be considered but practical issues with performance of the block and duration of action will often preclude its use. Many techniques of nerve blockade have been described in children, although only a few are commonly used that are simple, safe and effective (Table 6.5). Traditionally, insertion has been guided by anatomical landmarks but newer methods such as ultrasound and electrical surface mapping may potentially add to the efficacy and safety of the techniques.

Table 6.5 Some commonly used nerve blocks in children.

| Block | Procedure |

| Wound infiltration | Most surgical wounds |

| Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks | Inguinal hernia repair, orchidopexy |

| Dorsal nerve of the penis | Circumcision |

| Rectus sheath block | Umbilical hernia repair, laparoscopic port site |

| Axillary brachial plexus block | Hand surgery |

| Infra-orbital nerve block | Cleft palate surgery |

| Femoral, sciatic or fascia iliaca block | Surgery to thigh or femur |

| Intercostal nerve block | Thoracotomy |

| Paravertebral block | Thoracotomy, abdominal surgery |

| Epidural: caudal, lumbar or thoracic | Abdominal or genitourinary surgery, orthopaedic or spinal surgery, thoracotomy, cardiac surgery |

Bupivacaine has been the local anaesthetic of choice in paediatric practice. It has been extensively studied and safe dosing guidelines have been established that have greatly decrease the incidence of systemic toxicity. Neonates demonstrate decreased clearance, increased half-life and decreased protein binding of local anaesthetic agents. Therefore, at this age there is a risk of systemic toxicity, and dosing schedules have to be adjusted. More recently, ropivacaine and levobupivacaine have been introduced into paediatric practice and have demonstrated both efficacy and safety.

Single-shot techniques

These can be used to provide excellent intraoperative and early postoperative analgesia. They decrease the need for other analgesics, the incidence of side effects, and potentially permit the avoidance of the use of opioids. However, the analgesic plan formulated must allow for sufficient analgesia to be in use when the effect of the block wears off. Caudal analgesia remains popular due to its versatility and simplicity. Adjuncts are often added to extend the spread and duration of the block. Ketamine and clonidine have been shown to be effective, with a low incidence of side effects at low doses. However, concern has been expressed about their effects on the developing nervous system, and their use by this route in the neonate and infant has been questioned. Caudal opioids are associated with an increased incidence of side effects and are not now commonly used.

Infusion techniques

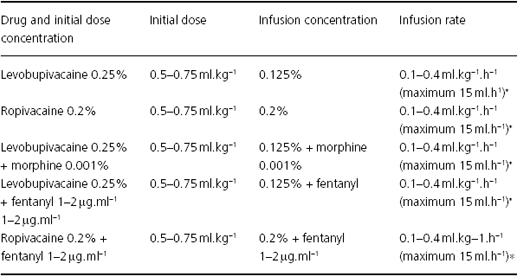

Continuous local anaesthetic infusions can be used to extend the duration of nerve blockade in the postoperative period. Accumulation of local anaesthetic is a factor in children, and potential toxicity can limit the duration and efficacy of an infusion. Local infection at the insertion site and catheter occlusion or dislodgement can also occur, especially in smaller children. Lumbar and thoracic epidural infusions are well established in children for the treatment of severe, acute pain. Efficacy and postoperative respiratory benefits have been demonstrated in children but the relative benefits and risks in comparison with other techniques have not been well studied. Generally, insertion is performed with the child asleep, and most practitioners use a continuous loss of resistance to saline technique. Opioids and clonidine have been used as adjuncts to the local anaesthetic to improve efficacy and limit local anaesthetic usage. Some common infusion regimens are given in Table 6.6. Clear and established protocols for the management of epidural infusions must be in place in addition to trained staff, appropriate monitoring and a safe environment. Treatment protocols for side effects should also be used, and urinary catheterisation is recommended if opioids are added to local anaesthetic solutions. Continuous infusion techniques for intrapleural, paravertebral, brachial plexus block, sciatic nerve block, fascia iliaca compartment block and popliteal block have all been reported in children.

Table 6.6 Drug concentrations and infusion rates recommended for epidural analgesia.

*Maximum infusion rate in neonates = 0.2 ml.h−1.

Clonidine

Clonidine is an α2-adrenergic agonist that has a wide range of uses in children. It can be used as part of a multimodal strategy for pain therapy by the oral, intravenous and epidural routes, and is often used as an adjunct to local anaesthetics. Principally, it is used as a perioperative analgesic, but it is also used in some chronic pain situations as an adjunct to or replacement for opioid infusions, for symptomatic relief during opioid withdrawal, and as an infusion during intensive care. It is also used for premedication because of its sedative properties.

Ketamine

Ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist. It has analgesic properties in its own right at lower doses than those used for anaesthesia. It also prevents the induction of central sensitisation and wind-up, and the development of opioid tolerance. Its efficacy has been demonstrated in children when combined with opioids and local anaesthetics, and when used as part of a multimodal strategy. It is also used as an analgesic agent to treat neuropathic pain. At the low doses used for analgesia, the potential psychomimetic effects of ketamine are rare. It has also been used successfully for premedication.

Chronic pain

Chronic pain in children is an increasingly recognised clinical problem. Commonly seen causes include: chronic illnesses, e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, sickle cell, metabolic and immunological disease, and cancer; after injury or surgery, with or without nerve damage; neuropathic pain; chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS) types I or II; chronic or recurrent unexplained pain; headache. As well as pain, the effects of chronic pain states in children will include sleep disturbance, decreased school attendance, socialisation and physical activity, depressed mood or depression, and family disturbance. Treatment should adopt a multidisciplinary approach, involve a diverse range of healthcare professionals, be directed towards the underlying cause or pain mechanism, and also be aimed at associated symptoms such as muscle spasm, poor sleep patterns, anxiety or depression.

Pharmacological treatment includes the use of specific agents such as gabapentin, anticonvulsants and antidepressants, as well the more commonly used analgesics and treatments for pain-related symptoms such as anti-emetics, antispasmodics and muscle relaxants. However, drug therapy is often not successful in isolation, and in some situations can be of no benefit at all. Treatment regimens may also include the use of physiotherapy, psychology and pain coping strategies, occupational therapy, education and nonpharmacological treatments such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), massage, acupuncture and thermal therapy with hot or cold packs. Measures extending beyond the patient and their immediate symptoms may also be required, and can include family therapy and the involvement of community services such as education, mental health and social welfare.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

Postoperative nausea and vomiting are commonly seen in children. The causes are multifactorial, with analgesia, and especially opioids, often involved. However, pain can also be a factor, and adequate analgesia has been shown to reduce the incidence of PONV. Other risk factors include increasing age (>3 years), a history of PONV or motion sickness, the duration and type of surgery and the use of volatile anaesthetics. The effect of nitrous oxide on PONV has not been proven in children. Due to the complexity of the pathogenesis of PONV, it is postulated that a multimodal type strategy for treatment may give better outcomes. Ondansetron and dexamethasone are the most commonly used drugs, and combination therapy has been shown to be superior to either drug in isolation. Acustimulation using the P6 acupuncture point has been shown to be as effective as using anti-emetics.

References and further reading

1. Fitzgerald, M. & Walker, S.M. (2009) Nature Clinical Practice Neurology, 5, 35–50.

2. Wong, D.L. & Baker, C.M. (1988) Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs; 14, 9–17.

3. Merkel, S.L. et al. (1997) The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs; 23(3): 293–7.

4. Howard, R.F. (2008) Complex pain management. In: Hatch & Sumner’s Textbook of Paediatric Anaesthesia (eds R. Bingham, A. Lloyd-Thomas & M. Sury), 3rd edn, pp. 407–423. Hodder Arnold, London.

5. Lonnqvist, P-A. & Morton, N.S. (2005) Postoperative analgesia in infants and children. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 95, 59–68.

6. Howard, R.F. et al. (2008) Good practice in postoperative and procedural pain management. Pediatric Anesthesia, 18: Supp 1.

7. Gan, T.J. et al. (2003) Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 97, 62–71.