The western world's reluctance to look at positive images of female genitalia is perhaps summed up by one of the most famous journals in the world, Anne Frank's The Diary of a Young Girl. When it was originally published in 1947, many passages were omitted, amongst them several which focused on Anne's sexuality and her genitalia. At the time of publication, these entries were deemed to be too open about sex for a

THE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD

book which would be read by young adults. Anne Frank's diary was finally published in its entirety at the end of the twentieth century, following the death of her father. The following, written when Anne was fifteen, was one of the deleted passages. It is remarkable in its honesty, frankness and level of knowledge for a girl of her age in her society.

Friday, 24 March 1944

Dear Kitty,

... I'd like to ask Peter whether he knows what girls look like down there. I don't think boys are as complicated as girls. You can easily see what boys look like in photographs or pictures of male nudes, but with women it's different. In women, the genitals, or whatever they're called, are hidden between their legs. Peter has probably never seen a girl up close. To tell you the truth, neither have I. Boys are a lot easier. How on earth would I go about describing a girl's parts? I can tell from what he said that he doesn't know exactly how it all fits together. He was talking about the' 'Muttermund' [cervix], but that's on the inside, where you can't see it. Everything's pretty well arranged in us women. Until I was eleven or twelve, I didn't realise there was a second set of labia on the inside, since you couldn't see them. What's even funnier is that I thought urine came out of the clitoris. I asked Mother once what that little bump was, and she said she didn't know. She can really play dumb when she wants to!

But to get back to the subject. How on earth can you explain what it all looks like without any models? Shall I try anyway? Okay, here goes!

When you're standing up, all you see from the front is hair. Between your legs there are two soft, cushiony things, also covered with hair, which press together when you're standing, so you can't see what's inside. They separate when you sit down, and they're very red and quite fleshy on the inside. In the upper part, between the outer labia, there's a fold of skin that, on second thought, looks like a kind of blister. That's the clitoris. Then come the inner labia, which are also pressed together in a kind of crease. When they open up, you can see a fleshy little mound, no bigger than the top of my thumb. The upper part has a couple of holes in it, which is where the urine comes out. The lower part looks as if it were just skin, and yet that's where the vagina is. You can barely find it, because the folds of skin hide the opening. The hole's so small I can hardly imagine how a man could get in there, much less how a baby could come out. It's hard enough trying to get your index finger inside. That's all there is, and yet it plays such an important role!

Yours, Anne M. Frank

Anne Frank is to be applauded for her innocent teenage act of ana-suromai. More are needed. In the twenty-first century, we live increasingly in a world where the most common image of female genitalia is the one

THE STORY OF V

pushed by the pornography industry - and is a negative, shaming one. This representation - styled by men for men - bears scant resemblance to the varying beauty of unadulterated vaginas. Typically shorn of pubic hair, labia snipped into regular lengths, sanitised, neutered and surgically enhanced, pornography creates effigies of female genitalia. And for many men and women, such cunt caricatures are coming to be seen as a normal view of the vagina.

This is a sad, narrow and small representation of this amazing female organ of sexual reproduction and pleasure. Yet it seems that this journey-from the sacred to the profane for the origin of the world - is the one that will be made, unless we stop being ashamed and scared of what is really between a woman's legs. The way to alter this shameful attitude is to look at all the varying views of the vagina in an attempt to understand and appreciate what female genitalia actually embody - past and present, in art, history and science, and across cultures and languages.

2 FEMALIA

'... so he started playing the water over my legs and then directly on my ... femalia, and I held my lips open so that he could see my inner wishbone, and the drops of water exploding on it...' These are the words of the female protagonist of Vox, Nicolson Baker's erotic, arousing paean to phone sex. 'Femalia' is just one of the words invented in an attempt not to spoil the spoken sexual flow and throw an on-line orgasm off-course (there's 'strum' for masturbate and 'tock' for ass too). Femalia is also the word chosen by Joani Blank to title her fantastic book, which is full of colour photographs of female genitalia. Baker and Blank aren't alone in finding common terms for female genitalia too restrictive. For many, the conventional sexual lexicon is deeply unsatisfactory. Vulva, it's moaned, is too clinical, while vagina, others murmur, smacks too much of passivity. Pussy and other slang expressions, well, they suffer from being too laden with sexual stereotype, and cunt is just too hard to be heard. And then there's the fact that words for female genitalia often overlap and vary in meaning. Vulva generally describes the external female genitalia, but not always, while vagina can encompass all parts of the female sexual anatomy, minus the uterus, or refer specifically to the interior muscular organ.

So why, in the west, is the selection of suitable sexual terms to describe female genitalia so small and lacking in specificity? Well, for starters, the naming of any object is a tricky business - be it a child or a body part. What to focus on? There's so much to consider. Names say a lot. And what they convey can be of vital importance. An appropriate name can have great influence, but choose the wrong title and you may offend. Names, hopefully, should also stand the test of time. Yet fashion is fickle. Plump for popularity and the title could all too quickly fall from grace. Decide on a mouthful of a monicker, and the term may never take off. Interestingly, though, the fact that there are so many influences on the choice of a title means that language is capable of being a unique barometer of a society's attitudes. If you look closely, it can even expose how a society views the vagina - whether it's vaunted or vilified lexically. And if you get really close up, the history of sexual language can also explain the nature of the English sexual lexicon.

THE STORY OF V

Tellingly, names often reflect the beliefs and ideas of the time, and the field of sexual anatomy is no exception in this. For example, the term 'renal' is used today to denote an association with the kidneys (renes). However, the kidneys got their Latin name because it was believed that rivi ab his obsceni humoris nascuntur - the stream (rivus) of semen (obscenus humor) flows from them. This reflects the ancient theory that seminal matter (both the female variety, sperma muliebris, and the male form) was perfected in the lumbar region of the spine and kidneys (after originating in the brain). From ancient Greece through to the seventeenth -century, nymphae, meaning 'water goddesses', was a common name for a woman's inner labia. This accepted medical term stemmed from the idea that the labias' fluted design and position, surrounding a woman's vaginal and urethral openings, guided the gush and flow of both semen and urine away from female genitalia. It also reflected the practice in pre-Christian Greece of placing statues of nymphs near public fountains. As midwife Jane Sharp explained helpfully in The Midwives Book (1671): 'these wings are called Nymphs, because they joyn the passage of the Urine, and the neck of the Womb, out of which as out of Fountains ... waters and humours do flow, and besides in them is all the joy and delight of Venus'.

Some names either attempt to explain what an organ does or paint a mental picture of the part, often badly and baldly. Take cunnus interior and 'the king's highway' - both ancient expressions for the vagina. A woman's perineum, as it is known today, was formerly dubbed the inter-foramineum, literally, 'the space between the two holes' - vagina and rectum. Genital labia were sometimes referred to as the orae naturalium -'the edges of the natural parts' -while other anatomists preferred the more cumbersome monicker, the genitalis muliebris ambitus, the 'periphery of the female genital part'. In men, the vas deferens -the duct that transports spermatozoa from the epididymis to the urethra - is made up of two Latin words. Vas is a duct or tube that carries a fluid, and deferens is the past participle of the verb deferre, which means to bear away. Simple and to the point, and this term is still used today, despite losing something in translation over the centuries. An earlier Greek term for the vas deferens-'the swollen vein-like bystanders' - was far vaguer about function, and did not stand the test of time. The man who bestowed this graphic title, the Alexandrian anatomist Herophilus, also called a man's seminal vesicles 'the gland-like bystanders'. Perhaps Herophilus was suffering from anatomist's block.

Importantly, names can also be used to make a political point or emphasise a particular idea. The words 'genitals' and 'genitalia' derive from the depiction of these organs as parts of generation. It could be said there is a hidden agenda here, as such vocabulary places a specific function

FEMALIA

on genitalia. In this case the role rammed home is sexual reproduction, which is arguably not the predominant function of a person's genitalia. Conceiving children is certainly not the most common use the vagina and penis are put to. Significantly, what this terminology omits to mention is that these organs are also organs of ecstasy and pleasure, capable of generating orgasm as well as offspring.

Titles are often used to educate. And in some examples this education extends to prescribing what emotions are appropriate regarding particular body parts. In his medieval summing-up of ancient scientific knowledge, Etymologiarum, Isidore of Seville uses the term inhonesta -the parts which cannot honourably (honeste) be named - to describe female genitalia (turpia and obscenawere other sex-negative Latin expressions for the genitals). Isidore also explains how 'The ancients called the female genitalia the spurium', and goes on to amplify that this is why illegitimate children, those that do not 'take the name of the father' are called spurius, because they are seen to spring solely from the mother. Today spurious commonly means not genuine or real. Tellingly, a term used today to describe a person's genitals (in particular female genitalia) -pudendum (plural pudenda) - irrevocably associates shame with genitalia, as it is said to be derived from the Latin verb pudere, to be ashamed. Modern shaming connotations also linger on in other European languages, notably German. Terms for the female genitalia include Sch-amscheide (literally 'the sheath of shame'); Scham (genitalia); Schamhaar (pubic hair) and Schamlippen (the labia).

One of the most interesting aspects of language is that it is mutable, that is, over time words can change in meaning as they shift to reflect the predominant attitudes of the day. In this context, it is significant that a look at more archaic epithets for the genitals reveals that prior to the shift to Christianity, the western world did not view a woman's genitals in an inherently negative manner. Indeed, Greek words to describe genitalia can convey positive overtones. In classical Greek, people such as Hippocrates, Aristotle and Homer wrote about female genitalia using the term aidoion, which does not contain an anti-sexual judgement, and, as noted earlier, derives from a word meaning to stand in awe or to fear or regard with reverence. Likewise the Greek word verenda, which was used extensively by Pliny as an equivalent of aidoion. Verenda or, as we would say today, vagina, means literally the 'parts that inspire awe, or respect'.

Natura, another Latin term for female genitalia, was neither overtly vulgar nor technical, and was generally acceptable in educated language. Naturas origin is understood to lie in the word nascor, which indicates 'place of birth', i.e. the female genitalia. Natura in turn gave rise to naturale, which Celsus (c. 30 ce) used to describe the passageway of the vagina specifically. Etymologists also point out that even the word pudendum

THE STORY OF V

wasn't always read as a signifier of shame. When first used by Roman philosopher Seneca, it did not carry such connotations. Rather it was used to express seemingly indifferently the genitalia of both men and women. The western world has early Christians, such as Augustine, to thank for conflating human sexual organs, in particular the vagina, with shame. It appears that 'shameless' which can mean 'perfectly modest', was spun into something to be ashamed of, in order to stress a particular religious belief.

Entertainingly, the stress of the name game often prompts some peculiar appellations. Many of these, it seems, spring from the fact that sometimes it's simpler to attach a term that sets out to describe what the object resembles. The newborn baby reminds you of your Uncle Bob, so why not call her Bobbina, or even better, Roberta? This simile method for naming objects is common in anatomy. Hippocrates referred to a woman's plump, pillowy outer labia using the Greek for 'overhanging cliffs', while a later term was monticuli- hillocks. In contrast, the inner, thinner labia were likened to wings in both Greek and Latin. Mentula y an early name for the penis, has its roots in the term for spearmint stalk. Likewise the penile phrase caulis, which stems from another stalk, this time that of the cabbage.

The word 'penis', peculiarly, has its origin in the male member's similarity to a piece of animal anatomy. Put plainly, penis was an archaic word for an animal's tail. However, today it is the standard term for a man's phallus. How come? Well, it's suggested that the title was conferred in part because, like many animals' tails, the phallus could stiffen and rise, as well as hang down. (An understanding of this etymology of penis adds some resonance to the phrase 'sending someone away with their tail between their legs'.) Moreover, when first coined, penis was an exclusively obscene term for the phallus, not a conventional one. Cauda, the classical Latin word for tail, was also used in a similar way. And for whatever inexplicable reasons, penis is the simile that has stuck, while mentula, caulis and cauda fell from grace.

Of sheaths and scabbards

The word 'vagina', too, has its origins in the anatomical habit of using resemblances to bestow titles. In Latin, the word originally implied a sheath or scabbard, the protective covering for a sword. During the sixteenth century, though, this meaning began to change, and the word started to be used in conjunction with a specific portion of female sexual anatomy. The first person to apply vagina in this way is believed to be the Italian anatomist Matteo Realdo Colombo. In 1559, Colombo, writing in his manuscript De Re Anatomica, described a woman's interior erectile

FEMALIA

muscular sexual organ as 'that part into which the mentula [spearmint stalk/penis] is inserted, as it were, into a vagina [sheath/scabbard]'. As this Renaissance man saw it, this particular part of female sexual anatomy enveloped the penis just as a sheath or scabbard covers a sword. Hence to him it was a vagina.

It took nearly a hundred years, though, before the word vagina started to be used as a standard anatomical term. Its first appearance in this sense is credited to Johann Vesling, who in 1641 used it in his text Syntagma Anatomicum. Its take-up as a medical term appears to be fairly rapid after this. In 1682 vagina was used in English for the first time, and by the turn of the century the term (or its equivalent, such as vagin and Schiede) had entered European vernacular. From 1700 onwards, it became the term of choice in childbearing guides, such as Pierre Dionis' 1719 A General Treatise of Midwifery. Dionis describes how the vagina 'receives the Sword of the Male, and becomes a case to it, and therefore is call'd the Vagina, that is to say, its sheath'. The vagina had arrived. From conception to public acceptance in approximately 150 years. So, thanks to similes and early anatomists, humans have sex with sheaths and tails. It could have been worse, though; it could have been a combination of the king's highway and cabbage stalks.

However, the roots of some genital terms remain hazy. One of these is 'vulva'. According to the medieval manuscript De Secretis Mulierum ( Women s Secrets) by Pseudo-Albertus Magnus, 'the vulva is named from the word valva [folding door] because it is the door of the womb'. Seventeenth-century anatomist Reinier de Graaf agreed with this etymology, but added that others thought the derivation was 'from velle, "want", on the grounds that it has a great and insatiable want of coitus'. This recalls the infamous verse from Proverbs, Chapter 30: 'There are three things that cannot be sated ... Hell, the mouth of the vulva and the earth.'

Isidore of Seville (c. 560-636) used the term valvae (doors) to describe a woman's labia, while the Babylonian Talmud (fourth century ce) used an expression for hinges. However, others state that vulva means wrapper or covering. This alternative meaning is thought to derive either from the occasional use of the word in Roman times to describe the membrane which surrounds a developing foetus, or from its use as a term for the uterus. It's certainly the case that the archaic meaning of vulva was the uterus of an animal. More specifically, in the old dialect of Sassari, Sardinia, vulva was a culinary term for a sow's uterus, which was considered a delicate dish in Roman times. The word uterus, meanwhile, is thought to have its origins in the Roman word for belly {venter) , and could be applied to men as well as women. Shades of this uterus/belly conflation can be found in the still common habit of saying a woman has a baby in her tummy.

THE STORY OF V

Defining the vagina

Sometimes it's impossible to pin down why some names endure and others don't. However, to my mind, Colombo's vaginal conception may well have been successful because it fulfilled a particular and timely need -namely providing a specific term for a particular area of female sexual anatomy. Prior to this, the female genital lexicon in the sixteenth century appeared designed to confuse rather than clarify. Some vaginal phrases, like sinus pudoris, 'the hollow of modesty', were vague, while elsewhere words for the vagina, uterus and vulva overlapped in meaning. In the Latin of late antiquity, for example, vulva had various meanings. In some cases it implied the chamber of the vagina and the vestibule. In other situations, it implied the external female genitalia. The word vulva could also signify the uterus, or describe the uterus, vagina and vestibule as one entity.

However, from Aristotle onwards, it was how the uterus was conceptualised that was one of the commonest sources of genital confusion. Uterus was typically applied to describe the entirety of female genitalia, both outside and in, yet in some cases its meaning was the one it has today- namely, the womb, the organ that is home to a developing embryo. Uterus, though, could also imply the vaginal passageway, hence the description by one anatomical tome of how, in virgins, the hymen 'prevents the penis from being inserted in the uterus'. And as well as being both an all-encompassing genital term and a singular one, the uterus was also used as a reference point for the remainder of female genitalia. As a result, reading old anatomical texts is like swimming in an increasingly complex uterine sea. There's the mouth of the uterus, the neck of the uterus, the fundus, the horns of the uterus, the entrance of the uterus, the boundary stone, the pudendum of the uterus and the latera. Sometimes it seems that many anatomists were themselves unsure which bit of a woman's body they were discussing as they got lost in uterine terminology. To me, it sounds like the western world's antipathy towards women, sex and the vagina resulted in a severe lexical deficit surrounding female genitalia.

Not surprisingly, when vagina is used for the first time as a medical term (by Vesling), it is in a uterine context. For him the uterus comprised three portions - the fundus of the uterus, the neck of the uterus and the vagina of the uterus. However, not everyone agreed with his use of the word vagina. Many anatomists continued to refer to the vaginal chamber in a wholly uterine context - although it seems that no one could agree whether the vagina was the neck of the uterus, the mouth of the uterus, or the entrance of the uterus. In time, though, the introduction and acceptance of the word vagina did settle the uterine confusion, and talk

FEMALIA

of the vagina as the neck, mouth or entrance to the womb began to fall out of fashion. While thanks for this clarification must go in part to Colombo, another person deserves credit too.

That man is the seventeenth-century Dutch anatomist Reinier de Graaf (whose name now graces a female's Graafian follicles). De Graaf's 1672 magnum opus on female genitalia, The Treatise Concerning the Generative Organs of Women, set the Renaissance gold standard in understanding female sexual anatomy. In fifteen chapters, de Graaf set out to describe in detail a woman's genitals in terms of structure, language and function. In Chapter I, 'Setting Out the Topics', after commenting: 'It will be obvious to everyone ... how various is the use of the term uterus', he provides a breakdown of the female genital parts in tabular form. Chapter VII, entitled 'Concerning the Vagina of the Uterus', contains a discussion of vaginal vocabulary, both past and present, and all the potential pitfalls that vague and overlapping terminology can lead to. Critically, before beginning a vivid description of the vagina's design, position and proportions, he states: 'For this reason, so as to leave no room for confusion, we shall call this channel, in the following discussion, the vagina of the uterus. This is an appropriate name, since the part encloses the male member within itself, receiving it as a scabbard does a sword or knife.'

How the uterus got its horns

The distinct sexual lexicon created and promoted by de Graaf, Colombo and their contemporaries filled a much-needed gap in the language of female genitalia. Moreover, on close inspection the way that these men described women's sexual organs reveals another key aspect of the mutable nature of language. Fashion, favoured and then defunct theories, and a society's morals, all influence whether a certain word remains in common use. But there is another major reason why terminology fluctuates over time - human error. Sometimes it's clear how such mistakes occurred. Some slips were made as texts were translated over the centuries from Greek to Latin, or, more typically, from Greek to Arabic and then to Latin. Other shifts in sense are harder to pin down. And while some permutations are minor, others have altered meanings radically.

'Cervix' is one modern female genital term that bears the scars of human error made at some stage in its history, mistakes that changed its meaning drastically. In modern medical terminology, it is a term that is understood as meaning the short, thick tube of smooth muscle which surrounds the narrow channel (the endocervical canal) which leads from the vagina through to the uterus. The lower end of the cervix dips into the vaginal chamber, and is called the external os (opening, or mouth),

THE STORY OF V

while the upper uterine end of the cervix is known as the internal os. The intimate connection between the cervix and the uterus is highlighted in the full title of the cervix, the cervix uteri, which means the neck of the womb or neck of the uterus - a phrase that many medics continue to use (although the uterus is distinct from the cervix in terms of tissue type). Indeed, in medical terms, the term, cervical is understood in general as referring to the neck; for example, a person's cervical vertebrae are the top seven spinal bones - those in the vicinity of the neck.

Curiously, though, the word cervix did not originally mean neck. Collum is the Latin for neck. De Graaf uses the word collum when talking about the neck of the uterus (the cervix as we know it today). As de Graaf explains: 'The uterus is linked to the vagina, the rectum and the bladder by that part of it which is properly called the collum, neck.' Elsewhere he adds: 'The real collum of the uterus is the one where the narrow little hole is ... The semen proceeds through it into the fundus of the uterus.' De Graaf wasn't the only anatomist to call the neck of the uterus the collum. So do earlier anatomists, such as the second-century scientist Soranus, in his immensely influential book Gynaecology - the major source of information regarding female genitalia for the following fifteen centuries.

So if the neck of the uterus was known as the collum what was, or is, the original cervix of the uterus? The source of the word cervix lies, surreally, in the curving, crescent-shaped horns of many mammals. And curiously, although this horn meaning was somehow lost in human anatomical vocabulary, it survives today in animal physiology. A cervid is any ruminant mammal of the class Cervidae, mammals that are characterised by the presence of horns or antlers (in Latin, cervus means deer). Plus, it is still common today for scientists to talk of uterine horns, in particular when discussing animal anatomy although this is true of human anatomy too. As yet, it is unclear how collum became transposed with cervix.

What is certain, though, is that the belief that a woman's uterus had horns, as did the wombs of many other mammals, including cows, ewes, goats and rabbits, is a long-held one. Aristotle talks of the two horns of a woman's womb. So too do medieval anatomical manuscripts such as the Pantegniy which relates: 'The womb (matrix) is like the bladder in shape, for both of them are very deep, but it is different in its two extensions which are similar to horns.' The notion of the horned womb was also used to explain how an embryo's sex was determined. The left horn of the uterus, it was said, was responsible for the creation of female offspring, while the right resulted in boys. Hence the advice to women to lie on their left side during and after sex if they wanted to produce a girl.

The yoking of horns to a woman's uterus was accepted for centuries, as seventeenth-century descriptions of what we now call ectopic pregnancies make clear. In his text Anthropographia, anatomist Jean Riolan states:

FEMALIA

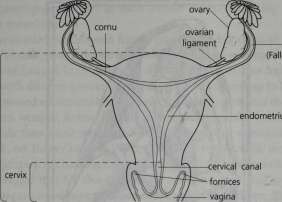

uterus

oviduct (Fallopian tube)

endometrium

cervical canal

fornices

vagina

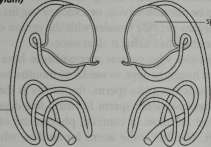

Figure 2.1 A woman's uterus and Fallopian tubes. It's striking how the exterior of the uterus does trace a bull's head shape with the Fallopian tubes in a position akin to where a bull's horns would be.

As I write this, 10 years have passed since a surgeon in Paris, with physicians present, found, in a dead woman he had dissected, a very small foetus excellently formed in the right horn of the uterus ... We have, too, the recent example of the laundress of the Queen's bed linen. Some years ago there was found in her body a foetus of the length and thickness of a thumb and well formed, resting inside one horn of the uterus. For 4 months it caused such cruel pains that at last the woman exchanged life for death, in the seventh month of her pregnancy.

The modern term for these uterine horns is, of course, the Fallopian tubes. Even the man whose name would later be applied to them - Gabriel Fallopius - described them in his manuscript, Observationes Anatomicae, in terms of their horn-like design. He comments how 'that thin and rather narrow seminary passage originates, nervous and white, in the horn of the uterus itself and when it has got a little way away from the horn gradually widens and curls itself like a vine-tendril until near its end'.

A bulVs head with horns

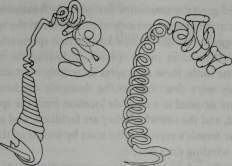

The conception of the Fallopian tubes as horns of the uterus is easily understood. A look at any modern illustration of a woman's uterus, or the real thing, reveals the source of the idea. Fallopian tubes do trace a graceful horn-like curve, and are positioned in conjunction with the uterus in such a way that it's not too fanciful to see them as mirroring the horns and antlers of deer or bulls (see Figure 2.1). The shape of the

THE STORY OF V

Figure 2.2 The uterus as bull's head with horns (from Jacopo Berengario, Isagoge brevis, 1522).

exterior of the uterus is also suggestive of a bull's head, being wider at the top than the bottom, thus adding weight to the idea of uterine horns. This structural similarity in outline, coupled with the ancient notion that the uterus had horns, is presumably the driving force behind the decision of Renaissance anatomists to depict women's uteri as two-horned organs.

Images of slender, curving, antler-like Fallopian tubes appear on the pages of Belgian anatomist Andreas Vesalius' pioneering anatomical text De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1541), while shorter, thicker uterine horns adorn Jacopo Berengario da Carpi's illustrated anatomy book. Another of Berengario's drawings depicts an astonishingly bull's-head-like uterus, complete with horns (see Figure 2.2). Indeed, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when anatomical texts began to be illustrated for the first time, it seems routine to depict a woman's uterus with horns. This artistic habit, of course, in turn gave further credence to the scientific notion that uteri did have horns. Berengario's text labels the uterine ligaments as Ligamentum cornulae (cornu is Latin for horn, while korone is the Greek for anything curved), while the Fallopian tubes themselves are entitled the vas spermaticum - the semen-delivering vessels - reflecting

FEMALIA

the contemporary belief in their female-semen-delivering function (of which more later).

The connection between female genitalia and horns is an ancient one. As we've seen, one of the earliest stone carvings of women, the prehistoric Venus of Laussel (c. 24,000 bce) depicts a woman, one hand holding a horn with thirteen grooves, and the other hand pointing to her genitalia. Fast forward approximately eighteen thousand years, and the association between women, horns, fertility and female genitalia is still being spelt out, this time more strongly. The early Neolithic community of £atal Hiiyuk, on Turkey's Konya Plain, flourished from c. 6500 bce for around ten centuries. Archaeological evidence from this important Stone Age site has revealed that for this culture the two most common religious icons are images of goddesses and, in conjunction with them, illustrations of bull's heads and horns (the archaeological term is bucranium). The goddess and her bucrania are found embellishing temples, shrines and the walls of ordinary buildings too. One beautiful temple painting shows female torsos with bull's head and horns in place of their uterus and Fallopian tubes. The connection is unequivocal. On some images it even appears as if the artist has tried to represent the flower-like ends of the Fallopian tubes, as rosettes appear on the horns. The concept of reproduction was certainly known in the culture of £atal Hiiyuk, and is pictorially explained on a grey stone plaque. One side depicts the bodies of two lovers, the other a woman holding an infant.

The later Greek Minoan civilisation (2900-1200 bce) also has at its centre the same two iconic images - the figure of a goddess and her bull's horns - with both found adorning altars, shrines, sealstones and the walls of buildings. The presence of Minoan horns, which are known as horns of consecration, has come to be recognised as a clear indication of a shrine, and the double axe (the labrys) that the goddesses commonly hold aloft is seen as a symbol of power in Minoan religion. In some images, the Minoan goddess wears a crown made of bull's horns. Although gods do appear in Minoan images, when gods and goddesses appear together, the goddess is always larger than the male.

The archaic association between horns, fertility and the uterus is also reflected in ancient and modern language - both written and gestural. The Egyptian hieroglyph for womb is a two-horned bovine uterus, while the word cornucopia - 'the horn of plenty' - means both a great abundance, and a horn-shaped container. The horn of plenty is also read as a symbol of fertility, and in Tibet is associated with the white moon-cow goddess. In Italy, if a man is given the sign of the horn (index and small finger extended, the others folded in), it is one of the worst insults possible. The implication of this gesture is that his wife is unfaithful to him, he is being cuckolded (another man's sperm could be in the horns of her

THE STORY OF V

uterus). Moreover, the Italian verb cornificare .means to be unfaithful to, while cornuto means, cuckolded.

Significantly, the association between a man being cuckolded and horns is prevalent across all of southern Europe. In Portuguese (cornudo or cabrao); Spanish (cornudo); Catalan (cornut or cubron); French (cocu) and Greek (keratas), the word for cuckolded means 'the horned one', someone 'who wears the horns'. In England, cornute was introduced as a word during the Norman Conquest and remained in use until the sixteenth century. However, it was then to be replaced by 'cuckolded', a word which derives from cuckoo - the bird that lays its eggs in others' nests. Tellingly, cuckolded is a term that is applied to men, not women. That is, of course, because women cannot be cuckolded; it is a unique male fear that they cannot be certain that a child is theirs. Other connections between horns, fertility and the uterus remain. For the English, to be horny is, of course, to be sexually excited. And according to scientific studies, a woman's libido often reaches a peak when an ovum is released into her uterine horns. Cornification is the medical term for the change in structure of the outer layer of vaginal epithelial cells that occurs during oestrus and ovulation.

The vagina is a penis?

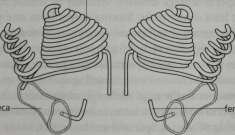

The notion that women had horned uteri was not the only one to be overplayed in anatomical illustrations and scientific theory. Renaissance medicine was also under the apprehension that the vagina was equivalent to an interior penis, and medical drawings depicted this vagina/penis conception with a peculiar precision. These illustrations, rather start-lingly, outline the difference between female and male genitalia as a spatial, rather than a structural one. One of the most astonishing visual renderings of the vagina as a penis is by Vesalius, and features in his text De Humani Corporis Fabrica, the founding work of modern anatomy (see Figure 2.3). Indeed, the vagina is represented as a penis in all three of Vesalius' works. Moreover, as these manuscripts were all widely plagiarised by other anatomists, the habit of representing the vagina as an interior penis became routine in Renaissance anatomical texts. Vesalius' drawings comparing side by side a woman's female sexual anatomy with that of a man (see Figure 2.4) were also reproduced cheaply in a format that was available to non-academics, and so this idea of the vagina as an interior penis entered public consciousness too.

But why did Renaissance men perceive the vagina to be none other than an interior penis? Well, this phallic-centred belief has a lengthy history. Its roots are in antiquity, in theories that both Aristotle and later the physician to the gladiators, Galen (c. 129-200), propounded.

FEMALIA

DE HVMANI CORPORIS FABRICA LIBER V.

V I G E S I M A S E P T I M A QVINTI

yki^iESENS figura utcrum

acorporeexeclum ea magnitudine re*

fcrt, qua pofhemo V atauij difje&a;

mulicris uterus nobis occurrit. atqs ut

uteri circunferiptionem hie exprefii^

inusjtactMmipjitisfindumper mediu

difjecuimus , ut illius finus in confpe *

clum ueniret, una cum ambarum uteri

tunicaru in non pragnantibttsjubjlan*

tix crafiitic. J[, \^4- B } B JSterifundifinus-C,D Linea quodamodo inflar futur<r, qua

fcortum donaturjn uterifundiJinum le

niter prrotuber an s. £ } E Interioris ac propria?fimdi uteri tuni

c<? crafiitics. F,F Interior isfindi uteri portio,ex elatio

ri uterifede deorfum injundijtnupro*

tuberans* Q,G Fundi uteri oriRcium. H,H Secundum exteriMfyfundiuteriinw

lucrum,a peritona?o pronatum. 1,1 et c. M.embranarumaperitona'opro

natarum, w uterum continentiumpor

tionem utrinqj hie afjeruauimus. K Vteri ceruicisjubflantia hk quoqtte

conjpicitur, quodfeftio qua uterifuns

dum diuifimus 3 inibi incipiebatur, L Veficx ceruicispars,uteri clriiici in<>

ferta,ac urinam in illam proijeiens.

Vteri colles, wfi quid hie fpefladuot

fltreliqui,etiamnullisappofitis cb.ira

cleribus, nulli non patent . Hw^iRm!'

% ViCHv

w

1

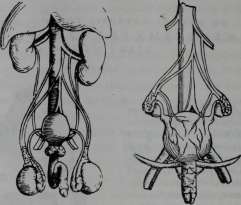

Figure 2.3 The vagina as penis: Vesalius' view of the vagina (1541).

THE STORY OF V

Figure 2.4 How female and male genitalia were seen to compare - male left, female right (from Vesalius, Tabulae sex, 1538).

According to Aristotle and his followers, heat, or more precisely how much heat a person possessed, was the factor determining whether an individual ended up female or male. Males, these minds opined, had more of this precious heat than females, a fact which made them men. Objects, too, were given a gender according to their heat or fire factor. In this system, the fiery hot and dry sun was seen as masculine, while the moon, on account of its cold and moist properties, was viewed as feminine. Heat or fire was just one of the four elements that ancient scientists saw as making up the natural world. The others were air, which was understood as moist and hot; earth -cold and dry; and water - cold and moist. However, these four elements were not seen as equal. Fire was rated ahead of the other three as it was both hot and dry - things hot and dry were superior to those that were cold and moist. Hence, fire or heat came first, and water last - a completely arbitrary ranking, it must be stressed.

In On the Usefulness of the Parts, Galen enunciates how this female/male heat differential affects the sexes' genitalia, commenting: 'The woman is less perfect than the man in respect to the generative parts. For the parts were formed within her when she was still a foetus, but could not because of the defect in heat emerge and project on the outside.' Women, Galen is saying, do not possess the necessary heat to unfurl their phalluses. Instead, because of their cooler, moister nature, they are left with an interior, un-pushed-out penis. As the men of antiquity saw it, in essence, vagina and penis were alike. It was their position in space that separated them, not their underlying structure. As Galen put it: 'Turn outward the woman's, turn inward, so to speak, arid fold double the man's [genitalia], and you will find the same in both in every respect.' This vagina/penis

FEMALIA

analogy explains why many genitalic terms, such as 'spermatic vessel', and the Latin veretrutn, could be applied equally to the vagina or the penis.

Using a man's genitals as the yardstick with which to grade a woman's genitalia was not the only outcome of the heat differential theory. This entirely arbitrary hierarchy of elements also gave the authorities of the day (who were male) a system within which they could rate man above woman. Man became the measure of woman and all other things. Women were defined inferior because of this lesser 'heat' in relation to men. The whimsy of placing fire above water in an elemental scale meant that Aristotle could rationally say: 'For the female is, as it were, a mutilated male.' This subjective superiority scale has also led to, and underscored, a multitude of other misogynies.

Many male minds have used Aristotle's heat theory of sexual difference to put forward their own deranged and deeply distorted views of women. Galen explains his view of how heat grades human and animal life in the following way: 'Now just as mankind is the most perfect of all animals, so within mankind, the man is more perfect than the woman, and the reason for his perfection is his excess heat, for heat is Nature's primary instrument.' In the medieval text, Women's Secrets, the author states of female offspring: 'If a female results, this is because of certain factors hindering the disposition of the matter, and thus it has been said that woman is not human, but a monster in nature.' From a mutilated man to a monster, and all because of an arbitrary scaling system.

When girls become boys

The theory that it was a matter of heat that was at the root of the difference between men and women had consequences other than imagining the vagina was an interior and inferior penis, and that women were less evolved than men. One notion that followed on from the theory of fire was that it was possible for women to turn into men. Curiously, medical documentation from the first century through to the seventeenth contains many examples of cases where such a sex transformation was seen to occur. One of these is the story of Marie Gamier, a servant in the employ of France's King Charles IX. According to the king's chief surgeon, Ambroise Pare, at the age of fifteen Marie showed 'no mark of masculinity'. However, while in the 'heat' of puberty, Marie was chasing pigs through a wheatfield, and, while jumping a ditch, sprouted an external penis; or as Pare put it: 'at that very moment the genitalia and the male rod came to be developed in him, having ruptured the ligaments by which they had been held enclosed'. Marie returned home to his/her mother, who took her child to a bishop, who proclaimed Marie to be a man. And so Marie became Germain, or Marie-Germain.

THE STORY OF V

Marie-Germain's crime, and the reason why she changed sex, was, authorities explained, to indulge in inappropriate behaviour, moving in such a swift and violent (read unladylike) way that she shook out her internal genitalia. According to the heat theory, this occurred because 'the heat, having been rendered more vigorous, thrusts the testes outward'. Another account of Marie's sex transformation added ominously that in that part of France there was now 'a song commonly in the girls' mouths, in which they warn one another not to stretch their legs too wide for fear of becoming males, like Marie-Germain'. Fortuitously for men, however, they did not have to watch their stride in the same way, as such sex transformations were perceived to be one-way only. As the anatomist Gaspard Bauhin (1560-1624), explained it, 'we therefore never find in any true story that any man ever became a woman, because Nature tends always toward what is most perfect and not, on the contrary, to perform in such a way that what is perfect should become imperfect'. Woman was put firmly in her place yet again - beneath man, and with her legs placed carefully together.

Science would today suggest that the cases of girls who became boys at puberty were in fact feeling the effects of a genetic hormonal imbalance. This imbalance is known as 5-alpha-reductase syndrome, and results from a failure to produce the enzyme 5-alpha-reductase (which converts testosterone into 5-alpha-dihydrotestosterone). Although defined as genetically male - i.e. they have an X and a Y sex chromosome - such children are born with external genitalia that resemble female genitalia. This 'female' appearance occurs because their testes remain undescended, inside their body, leaving their scrotal sac looking like outer labia, and their penises are typically so short and stubby that they seem to be akin to a large clitoris. The only clue that this is not a typical clitoris is that they urinate through it.

These children 'become' boys at puberty, when steep hormonal changes cause the male genitalia to continue developing - their 'labia' swell and sag, testes descend, and the phallus lengthens. After puberty, their genitalia do not appear too different from other males, and many individuals go on to father children. In fact, in some areas of the Dominican Republic, this condition is so common that there is even a colloquial name for the affected children - guavedoces, 'eggs at twelve'. Interestingly, the idea of a third sex is accepted here without social stigma. One reason for this is probably the prevalence of guavedoces. Doctors in the region are also adept at recognising which girls will become boys, so the affected children do not have to suffer the shock of swapping sex unexpectedly.

FEMALIA

Women have testicles too

Another consequence of the ancient habit of viewing the vagina as the penis was that other genital congruences could be called into play in the anatomy game. In this strange one-sex scenario, where the vagina was seen as an interior penis, it was also argued that the uterus was a scrotum, a woman's inner labia were equivalent to a man's foreskin, and the ovaries were testicles. As Galen commented: 'All the male genital parts are also found in women ... you could not find a single male part left over that had not simply changed its position.' To illustrate his point of view, Galen gives a step-by-step account of how the two sexes' genitalia measure up:

Think first, please, of the man's [external genitalia] turned in and extending inward between the rectum and the bladder. If this should happen, the scrotum would necessarily take the place of the uterus with the testes lying outside, next to it on either side; the penis of the male becomes the passageway that the hollow creates, and the part situated at the tip, now called 'prepuce', becomes the external genital parts of the woman.

He then continues with a mental manipulation of a woman's genitalia.

Think too, please, of.., the uterus turned outward and projecting. Would not the testes [ovaries] then necessarily be inside it? Would it not contain them like a scrotum? Would not the neck [the cervix and vagina], hitherto concealed inside the perineum but now pendant, be made into the male member?

This anatomy of female/male genital correspondences, using man as the measure of woman, was, in fact, the prevailing one in scientific lore for at least two thousand years - from the third century bce through to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries ce. (Some argue that it is still the case today.) It's important to realise, though, that Galen's confidence about the structure of female genitalia was not based on actual dissection experience. He had examined dead male gladiators, yes, but his experience of dissecting the female of the species was confined to pigs, goats and monkeys. Instead of direct evidence, Galen based his theories on the work of the anatomist Herophilus, who lived and worked in Alexandria in the third century bce. Herophilus had viewed a woman's internal sexual anatomy; indeed, it was he who discovered a woman's ovaries. However, steeped as he was in Aristotelian ideas of man as the measure of all things, with women simply a lesser version of this perfect male human blueprint, Herophilus chose to see the ovaries as a version of a man's testicles. Galen, with no physical evidence to the contrary, in fact, no physical evidence at all, appears to have simply gone along with Herophilus' hypotheses, fitting

THE STORY OF V

as they did with his own world view - that .women were an imperfect version of men because of their lesser 'heat'.

While Galen's persistence in seeing woman as an inverted man is perhaps understandable in light of the lack of physical evidence to the contrary, the confidence with which Renaissance anatomists continued to repeat this dogma is disturbing. From the fourteenth century onwards, female bodies were made available for dissection. Pioneering sixteenth-century anatomist Vesalius is known to have based his drawings of female genitalia in De Humani Corporis Fabrica on at least nine female bodies. 'The books contain pictures of all parts inserted into the context of the narrative, so that the dissected body is placed, so to speak, before the eyes of those studying the works of nature' is his boast of his illustrated anatomical texts. Yet what the reader actually saw was the product of Vesalius' prior ideologies, not the product of accurate observation, as we've seen.

For Vesalius and his peers, seeing was most definitely not believing. These anatomists may have been Renaissance men in that they lived through this period of time; however, the majority of them were still in large part simply sheep, following old doctrine blindly, and held in sway by the scientific and religious conventions of the day. The science of anatomy suffered for this. No image, verbal or visual, existed independently of an 'authority' decreeing why it should be so. For Aristotelians it was the lack of 'heat' that made women inferior to men; later, the Christian church promoted the view that sexual differentiation was a result of Eve's actions in the Garden of Eden, i.e., women had fallen from grace and it showed in their stunted genital shape. Renaissance anatomists promulgated and gave credence to both these absurdities. And so women continued to be viewed as just a lesser version of men.

Is it a bursa or a scrotal bag, ovaries or testes?

The idea of women as inverted men had a staggering - and extremely confusing - effect on the western world's sexual lexicon. Not only were female genitalia seen as a stunted version of the male's, they were referred to by the same names too. The name Herophilus bestowed on a woman's ovaries was didymi - the Greek word for 'twins' - because they always came in pairs. Didymi was also the standard term at the time for what we call today a man's testicles. Echoes of these twins remain in modern male anatomical terminology. The epididymis - the twisted sperm-carrying tube that runs along the posterior edge of each testicle - derives from epi, near or close to, and didymi, the twins.

Remnants of another bisexual Greek testicular term, orcheis, which Hippocrates and later Galen used, are also found in modern medical

FEMALIA

terminology. Inflammation of the testicles is known as orchitis, while orchidectomy is the surgical removal of the testes. Orchids, members of the plant species Orchis, are reputed to have received their name because they excite the 'Venereal appetite', and assist in conception because of 'their similitude of the Testicles' and because 'they also have the odour of the Seed'. Orchids were also believed to increase the production of semen.

In Roman times, didymi slipped from currency as the term for the ovaries. One replacement was testis (the Latin for 'witness'), or its diminutive testiculus. The modern term, testicle, derives from this diminutive, with testis (plural testes) remaining the same. Testis was the word bestowed on a woman's pair of ovaries and a man's twin testicles because in Roman times, for testimony to take place, it was ruled that there must be at least two people. This idea that there must be at least two people (witnesses) in order to bear testimony legally is still found today in modern legal settings, such as marriage ceremonies or will-making. 'Stones' was another term straddling both sexes. Even today, ovaries and testicles share a medical term - gonads, which derives from the Greek word for seed, gonos.

The conception of women as imperfect men, albeit with all the requisite parts, also had knock-on effects on theories of genital function. While both Galen and Herophilus regarded a woman's ovaries as analogous to men's testicles, Galen went a step further with his comparisons. Not content with a structural analogy, he postulated that men's and women's testicles shared the same function, namely to produce semen. However, women's semen was, of course, not as thick and hot as a man's because of her inherent cooler nature. 'Forthwith of course the female must have smaller, less perfect testes, and the semen generated in them must be scantier, colder and wetter (for these things too follow of necessity from the deficient heat),' Galen explains.

The uterus also bore the brunt of the male-centric way of looking at female sexual anatomy. Despite its thick, muscular structure in contrast to the thin skin of the scrotal sac, and despite its unique role in gestating a child, it was consistently perceived of as a simple scrotum (a word which is thought to have its roots in the Greek term for a leather bag). As one sixteenth-century Frenchman put it: l La matrice de lafemme nest que la bourse et verge reversee de Yhomme - 'The matrix [uterus] of the woman is nothing but the scrotum and penis of the man inverted.' And as with the vagina/penis theory, this uterus/scrotum analogy was promulgated pictorially as well as lexically.

During the Middle Ages, the word bursa, which implies a bag, purse or sack, was used to describe the womb as well as the scrotum. One of the most popular medieval sex manuals, De Secretis Mulierum, explains how, after a man ejaculates, the woman's uterus 'shuts like a bursa [purse]'. In

THE STORY OF V

Renaissance England, 'purse' was commonplace as a term for both uterus and scrotum. 'The uterus is a tightly sealed vessel, similar to a coin purse,' states an anonymous German text. However, in the French word, bourse, which implies a place where moneymakers gather as well as a purse or bag, there is some sense of the uterus being a place where something of value is produced. This sense is also present in matrice, or the English version matrix, a word for uterus which derives from mater, meaning mother. A matrix is a place where something has its origin, where something of value is produced. Matrix (and fundament), unlike other uterine and scrotal epithets, applied only to the female.

A vaginal renaissance?

The seventeenth century was a good one for female genitalia. Not only was it the period in which the word vagina came into its own as a specific anatomical term, this was also the century that first heard opposition to the 'woman is an inverted man' theory of genitalia. Thankfully, some brave scientists dared to state what they saw, rather than repeat the accepted and ancient viewpoints. One non-conformist was the English anatomist Helkiah Crooke, who argued in 1615 against 'any similitude betweene the bottome of the womb inverted, and the scrotum or cod of a man'. According to Crooke, the skin of the 'bottom of the wombe is a very thicke and tight membrane, all fleshy within', while 'the cod is a rugous and thin skin', hence the two should not be seen as analogous. The seventeenth-century Danish anatomist Kaspar Bartholin was another dissenter, arguing astutely: 'We must not think with Galen ... and others, that these female genital parts differ from those of men only in situation.' To do that, Bartholin suggested, would be to fall in line with an ideological plot 'hatched by those who accounted a woman to be only an imperfect man'. Meanwhile, the Dutch anatomist Reinier de Graaf wrote: 'The notion of some people that the vagina corresponds with the penis of males, differing only in being inside rather than out, we say is ridiculous. The vagina bears no similarity at all to the penis.'

De Graaf also observed that women's 'testicles' did not look like men's testicles, and, more importantly, he said so. 'The testicles of the female differ greatly from those of the male ... in their position, shape, size, substance, integuments and function. Their position is not outside the abdomen, as in men, but right inside the abdominal cavity, each one about two finger-breadths from the fundus of the uterus.' Partly backed up by research from his peer, Jan Swammerdam, de Graaf went on to refute the conventional function of a female's 'testicles', as well as their structure. This was not semen production, he suggested, but egg (or ova) formation. 'The common function of the female testicles is to generate

FEMALIA

the eggs, foster them and bring them to maturity. Thus, in women, they perform the same task as do the ovaries of birds. Hence they should be called women's ovaries rather than testicles, especially as they bear no similarity either in shape or content to the male testicles properly so-called.'

So a woman's gonads had a name of their own for the first time in their history, as well as a unique function ascribed to them - one that it was recognised men did not possess. By the eighteenth century, de Graaf's new ovarian terminology had taken hold, and women's testicles were no more. The word vagina had appeared, and along with the word came the conception of this muscular organ as a separate entity, and one that was not just an imperfect interpretation of the penis. Added to this was the fact that the uterus stopped being referred to using scrotal language. However, although it may have looked and sounded as if a vaginal Renaissance was finally taking place, the tradition of seeing woman as a stunted version of man had not been lost completely. One genital congruence did not fall by the wayside, and as the habit of viewing the vagina as an interior penis lost resonance, another raised its head - namely, the clitoris was a penis. An undersized, unevolved penis. This, sadly, is still a theory that is given credit today.

Quite how this clitoral/penile idea came about is unclear. Some researchers point to language, to errors in the translations of anatomical texts, others to the erectile capacity of both organs, how sexual arousal stiffens them both. The most famous British sex advice manual, Aristotle's Masterpiece (published in different forms from the seventeenth century through to the nineteenth), wrote of how the 'use and action of the clitoris in women is like that of the penis or yard in men, that is, erection'. In Latin, virga, meaning rod, could be the clitoris or the penis. For some anatomists, the clitoris was simply the membrum muliebrum, the female member. It's also hard to break habits, so for some it must have been simpler to see the clitoris as a penile equivalent than a genital entity in its own right. Perhaps laziness played a part, allowing man to continue to be the measure of woman.

When women had two penises

The habit of using a man's penis to grade a woman's genitalia led to some strange genital scenarios. Some manuscripts seemed to declare that women had two penises - a vaginal penis and a clitoral one too. Thomas Bartholin's 1668 Anatomy was one of these - despite his defence of women's genitalia differing from men's. For Bartholin, the vagina 'becomes longer or shorter, broader or narrower, and swells sundry ways according to the lust of the woman'. It 'is of a hard and nervous flesh, and

THE STORY OF V

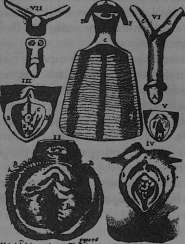

Tte FIGURES

Exptiined,

This T^BI/H ««n-preheodsthiS&eatbof the WomJ», the Body oftheCCtoris,andthe external Female Privity, both in Virgins, arid loth as are (Jeflou-rea,

FIG. I.

A A. The Bottom of tUWoni

diff:lUdcnfl-tttin. BB. Tht CrfVK/ tflbt Bet tan.

C. TltNtckofibtrKmb.

D. Xt* Mouth of tit Ntsk in 4 ttmui tbu b.vb tint * child.

EC. Tbt >u Si t,t ififidt ef tbt

Kt.-k.cot optn. FF. ThtrturutUttmeiUiefih

Worth cut tf.

FIG. II.

A. Tit Njmpb tt Cluini it*

tba iii in proper Situ* tics. BB. Ttit Hurt of lit Pnvilitt. C. Tit lnfe.tten of tbt Hick. •/

tbiBluldtr ntirtU Pti-

xur. DD. Tht Privity. LU. Tbt mtntj cftbt Privity. FF. Tit Neck, tf tU Womb cut

FIG. III. Tl>t Bet/ tf lit Clittti* Jlickjnn up tmitr tht Sbjn. 7h oit'tttLtfi of the Ptt-xtit fcfjt.tttJ me fiem 4-ntihtr. . Tie Ah' erminv, Attdibe

Kiin:bilib.nriftfip,u4it.1. «< —

fit Cjr uncle fUcti *bmt tbt UtMnlt (a) Ttrofltfy Mrttlffmp'd Piedntltmi. hiririhr Attorn Uxpuvfiotii wjneb etntdtntht Chink^

FIG. IV. Prefcms the Privily of a Giil. TU Chiotit. T!il.tiiotil:et*riviir. ■ TU mitf!trN)mt>lii. i. TU Onf.eoflbt VrtlhtnttPift-fift.

mnvmr&n%

. Ftut hhttltjlaf'J CjhiikIii. Tic iipntofl Cjttioile lel'tth itdividtiinto ttro t , fiittii tbt Pj/fit't oftU Pifi-pipe. TU title a, the Htmator Virginity-skin. Thrlitr:ftCjnmcli. Tbt FurMmatt.

cc

TttPtrintnrm FIG. V. Letter A. Shews ;heMca»6rane<lrav»»

crof. the Privity, which fomchavctakrntoba

tlic Hymen or Virginal-skin. FIG. VI. Shews die Clitoris iepararcd from

ihel'iivity. Tie trteftbt Clittti t refimllmi tht Hut if a TAuu

The Ftte-iliin ibttttf.

TkertPiiThi'hi of tleClittiit cvttfffrmlhtfrt* tubtttnej oj ih Hip or Huchje.

FIC. VII. The Clitoris cttt aliuulcr aihwait, its inward Ij'ungy Subftancc is ap parent.

Figure 2.5 The clitoris as penis (from Bartholin's 1668 Anatomy).

somewhat spongy, like the Yard'. However, the clitoris is also for Bartholin akin to 'the female yard or prick', as it resembles a man's yard in situation, substance, composition, repletion with spirits and erection', and it also 'hath somewhat like the nut and foreskin of a Man's Yard' (see Figure 2.5). Elsewhere, the seventeenth-century English midwifery manual, The Midwives Book, by Jane Sharp, talks on one page of how the vagina, 'which is the passage for the yard, resembleth it turn inward'. Yet in another paragraph, it states that it is the clitoris that resembles a penis, as 'it will stand and fall as the yard doth and makes women lustful and take delight in copulation'. The truth about the clitoris, as we'll see later, is something else altogether.

But first, why the word clitoris? It's such a particular term, so precise, and yet today it appears to convey very little of the nature of the subject. What does the word mean? Various sources are cited. Many etymologists claim that it is connected to kleitys, the Greek word for hill or slope, recalling the mons Veneris, the mount or mountain of Venus that it is said lovers of women must scale. Some wordsmiths point to clitoris being

FEMALIA

related to the Greek kleitos, meaning 'renowned, splendid or excellent'. Others suggest the Greek verb, kleiein, 'to close', or the Greek word for key, kleiSy making the clitoris the key, catch or hook with which one can open a door to pleasure (and bestowing an additional meaning on the phrase 'the key to the door'). Another possible association is the Dutch keest, meaning 'kernel or core'.

What is certain is that the word first appeared as an anatomical term in the writings of Rufus of Ephesus in the first century ce. Rufus also explained how clitoris, the word for the sexual organ, gave rise to the verb clitorising, meaning 'to make voluptuous strokings of the clitoris'. The German verb kitzlen, to tickle, and a colloquial term for clitoris, der Kitzler, 'tickler', are suggested to stem from this etymology. In this sense, clitoris stands out in the western world's lexicon of female genitalia. Unlike many other vaginal terms, it, and many of its nicknames, has associations with female sexual pleasure. For example, past clitoral descriptors include the amoris dulcedo, 'the sweetness of love'; the sedes libidinisy 'the seat of love'; the oestrus Veneris, 'the gadfly of Venus'; the Wollustorgan, 'the ecstasy organ'; and the gaude mini, 'great joy'. Then there's the fury and rage of love; the ear-between-the legs; and the myrtle-berry, so named because the myrtle was sacred to Aphrodite and Venus, the goddesses of love in Greek and Roman mythology respectively. In modern times, it is French clitoral terminology that conveys the sweetness and pleasure of the part with sobriquets such as bonbon, praline (sugared almond), framboise (raspberry), grain de cafe (coffee bean) and berlingot (humbug). My favourite French clitoral confection is la praline en delire, a phrase which translates as 'a delirious sugared almond', and implies a deeply aroused clitoris, one that is about to burst into orgasm.

Terms of endearment

While the history of vaginal language in the west is - in the main -characterised by a lack of words, both in terms of number and specificity, the same cannot be said of eastern cultures. As the ancient sex manuals of China, India and Japan show, when a culture's imagination soars, unfettered by repressive notions of sexuality, a wealth of vaginal language emerges. For instance, words describing female genitalia are commonly appellations of beauty and pleasure, reflecting a sense of delight in the visual, physical and olfactory aspects of the yoni or vagina. Chinese and Taoist vaginal terms include the 'doorway of life'; 'lotus of her wisdom'; 'love grotto'; 'open peony blossom'; 'treasure house'; 'inner heart'; and 'heavenly gate'. Yoni, the eastern word for vagina, itself encompasses the meanings of womb, origin and source (as previously discussed). Moreover, the Sanskrit term bhaga, which means womb or yoni, also means

THE STORY OF V

wealth, luck and happiness. Significantly, its root, bhag, forms the core of words for both female genitalia and bliss and power. These include clitoris (bhagshishnaka); mons pubis (bhagpith); ecstasy (bhagananda); Divine One {bhagwan); mother or divine consciousness {bhagavat-cetana); divine power {bhagavatisakti) and devotee (bhagat). Bhaga is also said to signify that aspect of humans that is the 'divine enjoyer' of things both erotic and non-erotic, the bhagavat.

In the west, if one didn't know better, a look at centuries of paintings of naked woman would suggest that female pubic hair did not exist. For some reasons, pubic hair was problematic in the west - probably because it implied an animal sexual nature, which wouldn't fit with preconceived and moralistic notions of female sexuality. In stark contrast, in China, abundant luxurious pubic hair is a sign of passion and sensuality in a woman, and pubic hair that forms an equilateral triangle with an upward-directed growth is read as a sign of beauty. Yinmao is the common name for female pubic hair; however, if a woman has no pubic hair she is known as a 'white tiger'. Perhaps expressing the positive feelings about pubic hair, Chinese terms for it are particularly poetic. Phrases such as 'fragrant grass', 'black rose', 'sacred hair' and 'moss' elicit a sense of somewhere soft, sprung and scented, and reflect the fact that the area that is covered by pubic hair contains scent glands. The glands that are scattered throughout a woman's vulval skin, and are suggested to play a role in perfuming the pubis, are in Chinese called by the terms 'sun terrace', 'mixed rock' and 'infant girl'. In India the Sanskrit term purnacandra, meaning full moon, is the phrase for the vaginal glands, which are said to be filled with the 'juice of love'. Other Chinese terms for the vagina that carry aromatic overtones include 'pillow of musk', 'pure lily' and 'anemone of love'. However, how the vaginal phrase 'purple mushroom peak' came about is unclear.

'Hill of sedge' - a Chinese term for the mount of Venus, the cushion of fatty tissue that covers a woman's pubic bones - shares some similarity with the west, in that it too recalls the mons' appearance as a hill or mountain. However, 'hill of sedge' has other resonances. Sedge is any grasslike plant which typically grows on moist or wet ground. Moreover, another feature of sedge is that it has triangular stems, making the phrase hill of sedge particularly appropriate for a woman's pubic triangle. Botanical phrases also flourish in terminology for the small hood-like fold of skin just above the clitoris. In Chinese, this clitoral hood, which moves freely under a finger, and can cover the clitoral tip either partially or completely, is called the 'dark garden', 'god field' and 'grain seed'. There is no particular word to describe it in English. The highly sensitive area just below the tip of the clitoris, where the labia minora appear to meet, is known in China as the 'lute or lyre strings' (in English it is the frenulum,

FEMALIA

a word which originally meant 'the corner of the mouth where the lips join'). The lower meeting point of the inner labia is referred to as yii-li-the 'jade veins'. The labia minora themselves are known as 'red pearls' (diih-chu) or 'wheat buds'.

Just as in the west, many oriental genital terms owe their name to ideas of sexual function. These ideas, though, are not necessarily the ones espoused elsewhere. In Chinese thought, for example, it is the ovaries that are considered to contain a woman's yin energy, and are understood to contribute most of their energy during sexual arousal. They are the 'ovarian palace', the Kuan-Yuan. For men, the seat of male or yang energy is the testicles. However, the Chinese view another part of a female's sexual anatomy as being a seat of female, or yin, sexual energy. This other site is the perineum, or the Hui-Yin, the collection point of all yin energy. It is also known as the 'gate of death and life' (recalling the ancient ideas of female genitalia as the sacred gateway between worlds). Yet the perineum is an area which for the western world is not usually regarded as an important part of female genitalia, although it is exquisitely sensitive and is all too often cut unnecessarily during childbirth. In India too, the perineum is viewed as a centre of female sexual energy, and its Sanskrit name is yonisthana, the yoni place.

Gold, cinnabar and jade

As we've seen, names say a lot. So how about the following Taoist term for the uterus - the 'precious crucible'. What kind of message does that convey? The place where a unique, magical, life-giving transformation takes place, perhaps? This uterine phrase is, to my mind, light years away from the west's desire to see the womb as nothing more than an inverted scrotum and penis. Along with other eastern genital terminology, it reveals very clearly the different attitude to sex and female genitalia. As has already been noted, Taoism sees sex as sacred, whereas Christianity viewed it as sinful (and still does?). Significantly, other Chinese and Taoist words for the womb also convey the sense of a special or valuable site. These uterine terms include the 'children's palace' (tzu-tung), the 'palace of yin', 'the red chamber' (chu-shih), 'the jewel enclosure,' 'the heart of the peony', the 'inner heart' and the 'cinnabar cave'. 'Flower heart' and 'innermost knot' are two Chinese names for the cervix, or more specifically, the cervical orifice.

Looking at the orient's genital lexicon, some common threads emerge. One of these is the prominent role given to jewels and precious metals, minerals and stones as descriptors of female genitalia. For example, in Japan, the vagina is the 'gate of jewels', and according to Japanese folk belief there were three precious stones inside the vagina which moved

THE STORY OF V

during sex. It's also said that up until the nineteenth century, Japanese women carried a pearl inside their vaginas, and folklore warned that if it was taken out it would cause their death. Turning to minerals, cinnabar is the commonest denominator by far. We've already seen the 'cinnabar cave' as a term for the uterus, but what about the following general vaginal terms: the 'cinnabar cleft', the 'cinnabar hole', the 'cinnabar gate' and the 'cinnabar crevice'.

Crucially, an understanding of what cinnabar represented leads to an understanding of its use and highlights again the positive sacred light in which the vagina was viewed. For the Chinese, cinnabar was significant as a descriptor of female genitalia for two main reasons. First, its colour -a lustrous red or reddish-brownish hue, which recalled that of female genitalia and blood. Most important, though, was cinnabar's alchemical role. For in Taoist alchemy, cinnabar was one of the key symbols of transformation, which makes it a perfect word for describing female genitalia, which transform base matter into new life.

In terms of precious metals and stones, the Chinese favoured gold and jade as genital terms. Gold, of course, has been seen as an object of beauty, something to treasure, in the majority of world cultures. To use gold in conjunction with the vagina is therefore to acknowledge the precious nature of female sexual anatomy. Consider the following ways of describing the vagina: 'golden gully', 'golden doorway', 'golden gate', 'golden lotus' and 'golden furrow'. However, there is another reason for the frequent use of gold, and as we'll see, it ties in with the third typical genital descriptor -jade. This semi-precious green stone, a silicate of calcium and magnesium, is also found in many vaginal terms, including 'jade door', 'jade gate', 'jade cavern', 'jade gateway', 'jade veins', 'jade pavilion', 'pearl on the jade step' (clitoris) and 'jade chamber'. The 'jade chamber' is an ancient phrase for the vagina, and appears in the title of two of China's oldest extant sex manuals, Important Matters of the Jade Chamber, from the Pre-Sui Dynasty (c. fourth century, but before 581 ce), and Secret Instructions Concerning the lade Chamber, which also dates from the Pre-Sui Dynasty. Moreover, as well as having jade genitalia, women are said to produce 'jade juice' too, a fluid which promotes longevity in the man who can gather it with his 'jade stalk' (once again men have stalks for penises).

It is longevity that is the key to understanding the use of gold and jade as genital terms. For according to ancient Chinese thought, both gold and jade protected the body from decay - even after death. That is, they promoted longevity. Significantly, this idea ties in with ancient Taoist thought, which teaches that the vagina is the source of the elixir of life, and hence sex is a way of cheating death. Fascinatingly, this belief in the power of jade can be seen in many aspects of Chinese culture. The J Ching, the Taoist Book of Changes, states that 'Heaven is Jade.' And as the Chinese

FEMALIA

viewed jade as the key to everlasting life, the stone was ground into a powder and drunk or eaten as a literal elixir of life. Concubines also used jade as part of the tricks of their trade, because ground jade potions were said to have the power to improve sexual potency.

The associations between jade and genitalia go further than you might imagine. It's intriguing to see that the roots of the word jade are associated with sexual anatomy; that is, sexual anatomy as defined by Chinese medicine, which views the kidneys as sexual organs. One of the two varieties of jade, nephrite, is known as the kidney stone, because of the long-held belief that it was beneficial in treating kidney and sexual disorders. In fact, the word jade was coined by a sixteenth-century Spanish doctor and derives from the phrase piedras hijades, 'the colic stone' or literally, 'the stone of the flank' (the hips), because it was believed to cure renal colic and all known kidney ailments. In Chinese medicine the kidneys (including the adrenals) are considered part of a person's sexual geography, because they are understood as one of the principal storage sites of sexual energy (or jing), and hence have a key role to play in sexual arousal.

This linking of jade with the kidneys and sexual energy may also help to explain why 'to be jaded' means to be exhausted. It also recalls ancient western medical thought, which connected a person's kidneys with their sexual energy and semen. (Intriguingly, western medicine now recognises that there are a number of connections between the kidneys and sexuality, both hormonal and structural. For example, in embryonic life, an individual's gonads, be they ovaries or testicles, grow in intimate association with the kidneys, even incorporating unused renal pieces into them.)

Finally, and touchingly, in this look at the east's vaginal lexicon, there are some similarities in the different approaches to christening parts of female sexual anatomy. In both hemispheres, east and west, names for the clitoris focus on sexual pleasure and the importance of this sexual organ. Chinese clitoral phrases include 'seat of pleasure', 'pleasure place', 'golden tongue', 'golden terrace', 'jewel terrace' and 'jade terrace', while the Chinese ideogram for clitoris combines the words yin and tee, as the stem ( tee) of an aubergine is said to resemble the clitoris. In Japan, the clitoris is hoju, a term that in Buddhism also signifies the 'magic jewel of the dharma [the essential principle of the cosmos]'. In western sexual anatomy, a woman's vestibule is the oval-shaped entrance to her vagina and urethra which is visible when her inner vaginal lips are parted, while in architecture, a vestibule is a small hall or lobby at the entrance to a building or passageway. The Chinese language plays with similar associations, with phrases for this vaginal entrance including 'heavenly court' {t'ien-t'ing), 'secluded valley' (yu-ku) and 'examination hall'.

THE STORY OF V

First impressions

A view of the vagina by taking a tour of its lexical history would not be complete without considering 'cunt'. And although a remarkably direct expression, cunt has multiple meanings, depending on the country you find yourself in. In Spain, if you wish to express your delight in a delicious experience, a suitable comment might be that it is como comerle el cono a bocaos ('like eating cunt by the mouthful'). If you're in Britain, though, this phrase would not go down so well. Cunt, one of the oldest words for female genitalia, is also the most taboo. Yet in Spain it's not. In fact, cono is so common a word in Spain (albeit an expletive) that just as the English have been dubbed lesfuckoffsby the French, in Chile and Mexico, Spaniards are known as los conos. The Spanish seem to have had fun playing with their cono phrases. Otra pena pa mi cono - 'another pain in my cunt' - is said when one is faced with something extra to contend with. If you're fed up with something or someone, you can be estoy hasta el cono, 'up to your cunt with it'. And if you want to get across the fact that a place is completely out of the way, i.e. it is the back of beyond, you can use the common Spanish expression en el quinto cono - 'the fifth cunt'. It remains a mystery as to why a particularly remote area should be described as 'the fifth cunt'.