EVE S SECRETS

beat slowing to a quiver, his feet clenched and his leg muscles in spasm. It is only then that the male ejaculates semen from his cloaca (not his clitoris) on to the female's everted cloaca. Significantly, studies have shown that it is stimulation of the male's clitoris that is responsible for ejaculation. Whether or not stimulation of the female's clitoris is a factor in whether she everts her cloaca or accepts his sperm for fertilisation has not been looked at. However, the behaviour of these birds does underline the importance of clitoral stimulation for both sexes if successful sexual reproduction is to occur.

The way ahead

What this chapter has hopefully shown is the importance of the clitoris in ensuring sex is pleasurable - and hence more likely to be successful, rather than deadly, in terms of sexual reproduction. However, there is still a lot that needs to be learnt about female genitalia (both outside and in). One area that has not received much attention at all is the innervation of female genitalia, presumably because sexual arousal has until now not been seen as being important in terms of successful sexual reproduction. However, female genitalia are understood to be well supplied with sensory nerves. It's known, for instance, that stimulation around the clitoris, labia, vaginal opening, lower vagina and perineum is picked up primarily by the pudendal nerve, while the pelvic nerve transmits sensations from the vagina, urethra, prostate and cervix. The hypogastric and vagus nerves are also involved in triggering and maintaining female sexual arousal, and ultimately orgasm (as we'll see later).

Critically, though, the precise nature and location of all branches of these essential sensory genital nerves is not known. This means that these arousal-promoting nerves cannot be spared if a woman has to undergo any form of pelvic surgery. In contrast, nerve- and hence erection- and arousal-sparing surgery is a routine part of any pelvic operation on men. In this respect, as in many others, knowledge of female sexual anatomy and function still lags far behind that of male sexual anatomy and function. However, with increased awareness of the importance of the clitoris in supporting female sexual arousal and non-traumatic (i.e. successful) sexual intercourse, it is hoped that this will change in the near future.

One remaining controversy hanging over the clitoris in the twenty-first century is its name - and what it represents. Some groups are pushing to redefine the clitoris so that this one word encompasses many other parts of female sexual anatomy. Their desire is to see the clitoris as being composed of eighteen parts - including the inner labia, hymen, vestibular bulbs and pelvic floor muscles. Considering that female genitalia have been reduced so much in terms of stature and function in the past, I am

THE STORY OF V

loath to call these eighteen parts a clitoris. It is also, I believe, misleading and confusing to do this. It would be a step back, rather than forwards. The understanding of female genitalia needs to be expanded by words and images, not reduced in order to please some idea of what is politically correct.

I also feel uneasy that the desire to rename objects - such as insisting on the Fallopian tubes being the egg tubes, because Fallopius was a man, and the tubes are women's property - smacks of previous cultures' attempts to rewrite history to their liking. The Egyptians chiselled out hieroglyphs in an attempt to force their people to forget prior religions or ideas - today we try to alter language. Yet acknowledging history is essential, whether it is the history of anatomy or the history of language. What is important regarding the clitoris is appreciating its actual structure; understanding how the clitoris works in glorious concert with the rest of a woman's genitalia - outside and in; and realising that female and male genitalia are more similar than not - and that extends to their core role in sexual reproduction and pleasure.

Note

All the measurements given in this chapter relate to the handful of cadaver clitorises dissected in the name of research. They refer to the averages from both pre- and post-menopausal women. Importantly, these measurements should not be read as being set in stone, or as absolutes, or norms. Not enough research has yet been done to give any such lengths with certainty. Plus, all women vary, as do all men.

OPENING PANDORA'S BOX

A hungering maw. A gluttonous gullet. A toothed, voracious, ravenous, greedy chasm. Vagina dentata - the vagina with teeth - is an ancient anxious image that flows through folklore, mythology, literature, art and humankind's dreamworld. For many the most powerful of all vaginal myths and superstitions, the vagina dentata is also, perhaps, the most common. Its prevalence around the globe is stunning. Snapping and snarling, emasculating and mutilating men, the myth of the vagina dentata is to be found from North to South America, across Africa, and in India and Europe too. The omnipotence of this motif of the devouring vagina has also survived millennia, with many cultures' creation mythology imbued with castrating and deadly images. The first women of the Chaco Indians were said to have teeth in their vaginas with which they ate, and men could not approach them until the Chaco hero, Caroucho, broke the teeth out.

The Yanomamo of South America say that one of the first beings on earth was a woman whose vagina became a toothed mouth and cut off her partner's penis. In Polynesia, Hine-nui-te-po, the goddess of the underworld and the first female on earth, from whose womb all others fell, uses her vagina to slay Maui, the Polynesian hero. Maui crawls into Hine-nui-te-po's vagina in the hope of returning to her womb, thus cheating death and winning immortality. Instead, he is bitten in two by her vagina's snapping, lightning-generating flint edges, and so, because of his defeat by the goddess' vagina, all other mortals must die.

Psychology suggests that sexual folklore seethes with stories of snapping vaginal teeth because of male fears about what lies within the dark, unknowable, unseeable mysterious space that is the interior of the vagina. Others view vagina dentata images as the embodiment of masculine angst before the insatiable vortex of female sexual energy. In the stories themselves, the origin of female genital fangs and the reasons underlying their sometimes deadly behaviour are not always explained. In some, sources both material and spiritual are blamed. One North American Indian myth tells of how a meat-eating fish inhabits the vagina of the Terrible Mother. In the Middle Ages, Christian authorities pointed the

THE STORY OF V

finger at the moon and magic when trying to find an explanation for the so-called fact of witches stealing men's penises with their vaginal teeth.

The following fable from the Mehinaku, a tropical-forest-dwelling tribe of Brazil, intimates a male role in vaginal dentition:

In ancient times, there was an angry man who constantly berated others. One evening, a woman took many shells - they looked just like teeth - and put them in her inner labia. Later, when it got dark, the man wanted to have sex. 'Oh, she is beautiful,' he thought. The woman was pretending to sleep. 'Let's have sex,' he said. Oh, but his penis was big. In it went... it went all the way in ... Tsyuu! The vagina cut his penis right off, and he died right there, in the hammock.

This story, like many others, ends in the castration and death of the male.

In some folk legends, notably those of the Navajo and Apache, deadly toothed vaginas go one step further, and are described as detached organs, walking around independently and biting as they go. Just like the Baubo figurines described earlier, this is the vagina personified, but this time more terrifying - with teeth. For instance, New Mexico Jicarilla Apaches tell of a time when only four women in the world possessed vaginas. These women, known as the Vagina girls', had the form of women, but were in essence vaginas. They were also the daughters of a murderous monster called Kicking Monster.

Picture the scene. According to the legend, the house that the four vagina girls lived in was full of other vaginas, all hanging around on the walls. And understandably perhaps, rumours about the vagina girls and their house brought many men along the road to their door. But once there the men would be met by Kicking Monster, kicked into the house, never to return. This continued, so the story goes, with man after man disappearing, apparently swallowed up in the house of the four vagina girls with vaginas hanging from the walls. Enter Killer-of-Enemies, the marvellous boy hero:

Outwitting Kicking Monster, Killer-of-Enemies entered the house, and the four vagina girls approached him, craving intercourse. But he asked: "Where have all the men gone who were kicked into this place?' 'We ate them up,' they said, 'because we like to do that'; and they attempted to embrace him. But he held them off, shouting, 'Keep away. This is no way to use the vagina.' And he told them, 'First I must give you some medicine, which you have never tasted before, medicine made of sour berries; and then I'll do what you ask.' Whereupon he gave them sour berries of four kinds to eat. 'The vagina,' he said, 'is always sweet when you do like this.' The berries puckered their mouths, so that finally they could not chew at all, but only swallowed. They liked it very much, though ... When Killer-of-Enemies had come to them, they had had strong teeth with

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

which they had eaten their victims. But this medicine destroyed their teeth entirely.

Gruesomely, it is the removal of vaginal teeth (symbolising the devouring aspect of female sexuality) by brave male heroes that is a core component of many dentata stories. Pincers, flints, a piece of string, the berry medicine of Killer-of-Enemies, iron tongs, rocks and rods that are as thick or long as a penis, are all used as excision tools in a bid to tame the toothed vagina and create a compliant woman. Tellingly, in some instances it is only after a woman has had her teeth pulled - that is, she is tamed by having her spirit and insatiable threatening sexuality broken - that a man will marry her. In this sense, pulling vaginal teeth is a metaphor for how some men would like to make women meek and biddable, remoulded in a shape defined by them. In these stories, instead of shaming her into submission, physical means are used to tame her sexuality. The following depiction of dental extraction comes from India:

There was a Rakshasa's [demon's] daughter who had teeth in her vagina. When she saw a man, she would turn into a pretty girl, seduce him, cut off his penis, eat it herself and give the rest of his body to her tigers. One day she met seven brothers in the jungle and married the eldest so that she could sleep with them all. After some time she took the eldest boy to where the tigers lived, made him lie with her, cut off his penis, ate it and gave his body to the tigers. In the same way she killed six of the brothers till only the youngest one was left. When his turn came, the god who helped him sent him a dream. 'If you go with the girl,' said the god, 'make an iron tube, put it into her vagina and break her teeth.' The boy did this ...

Fashioning hard phallic weapons that will never be flaccid in the face of female genitalia is also a common thread in these vagina dentata myths. Presumably this relates to male fears of women's seemingly insatiable sexual nature, their ability to enjoy orgasm after orgasm with their genitalia when men may only be able to manage one before becoming limp. I'm sure it's no coincidence that sharp-edged devouring teeth are the female weapon of choice - they stand in stark opposition to male fears of a soft, impotent penis. Creating an alternative tool is at the heart of another story of seven siblings and their efforts to remove a woman's vaginal teeth. This is one of the Pre-Columbian myths of North American Indians, and is depicted in explicit eleventh-century ceramic Pueblo artwork (see Figure 5.1). This Mimbres myth bowl illustrates the final brother's efforts to remove a woman's vaginal teeth with a false penis made out of oak and hickory. Re-enactments of vagina tooth smashing can be found in some cultures' rituals. In Navajo and Apache folklore,

THE STORY OF V

Figure 5.1 The vagina dentata: round the world, art and myth tell of how men may meet their end if they dare to venture inside the deadly toothed vagina.

Monster-Slayer kills Filled Vagina, one of the more ferocious of her species, who mates with cacti, with a club. Today, the Pueblo and other native North Americans use a carved wooden phallus to symbolically break a vagina woman's teeth.

Not only teeth, but snakes and dragons too

Intriguingly, teeth are not the only terrifying object to be found in woman's extra orifice. Snakes also stream from the deep, dark, invisible vaginal interior in folklore and legend. Vagina snakes, so these stories relate, can bite off a man's penis, poison it, or kill the man. Some serpents lurk solely in the vaginas of virgins, and sting only the first man to venture inside. Among the Tembu it is said that women who crave sexual excitement may attract demonic serpents called Inyoka, who come to live in their vaginas and give them pleasure. Women can then send out their vagina snakes to bite any men they dislike, or those who don't pay attention to them. In Polynesia, where there are no snakes, voracious vagina eels come into play. In one tale from the Tuamotos Islands, the eels in a woman called Faumea's vagina kill all men. However, she teaches the

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

hero, Tagaroa, how to entice them outside, and so he sleeps with her in safety.

It seems that fears of what lies inside the vagina have allowed men's imaginations to run riot over the centuries. Men of Malekula talk mysteriously of a vagina spirit, called 'that which draws us to it so that it may devour us'. Hungry dragons too are often to be found inside the vagina of folklore and myth, and some have speculated that the many legends of brave heroes killing dragons with sharp-edged teeth are spin-offs from the original dragons in the vagina idea. If this is the case, good old St George, for killing England's symbolic vagina/female spirit. Vaginal teeth can also be metaphoric, as revealed by the Muslim belief that the vagina can 'bite off' a man's eye-beam, resulting in blindness for the man who is brave enough to look deep into its depths. It is said that a sultan of Damascus lost his sight in this manner, and had to travel to Sardinia to be cured by a miracle-working statue of the Virgin Mary - whose vagina is, of course, safely veiled by her ever-permanent hymen.

Apparently not content with arming the vagina with all things devouring and venomous, many cultures fill their mythology with stories of gruesome creatures that are women above, but hell-beasts below. The Greeks told of lustful she-demons born of the Libyan snake-goddess Lamia. Their name - laminae- means either 'lecherous vaginas' or 'gluttonous gullets'. Or how about the Naginis, Indian figures which are cobras from the waist down and goddesses from the waist up, or the Echidna, which appear as pretty nymphs on top and slithering snakes beneath. Even William Shakespeare had his King Lear fulminating in this way about women, suggesting that what is below is bad, and revealing his deepest fears about females. Lear, in his madness, cries:

Down from the waist they are Centaurs,

Though women all above:

But to the girdle do the Gods inherit,

Beneath is all the fiends':

There's hell, there's darkness, there is the

sulphurous pit, Burning, scalding ...

This angry, terrified view of women, what is below their waists and between their legs, is deeply disturbing. And yet it is one that is painted over and over again. It also pops up in interpretations of one of the classic Greek myths, the story of Pandora, whose name means 'the all-giving' or gift to all'. According to Greek mythology, Pandora was the world's first woman and the one to blame for all the 'ills that beset men'. Her crime? It's said that she opened a box or vessel which contained all the evils of the world, letting them out and leaving only hope remaining inside. Does

, 4^Vfl, fO: . <a<> Ki'Ahr An ll^ ^ a h ifaMJt'^ „

Figure 5.2 Pandora's box as envisaged by Paul Klee.

Pandora's box have genitalic connections? Well, some have certainly read it as a symbol of female genitalia. The artist Abraham van Diepenbeeck placed Pandora's vessel suggestively over her vagina, and, of course, box is slang for the vagina. Paul Klee's twentieth-century response to the centuries-old myth is more vaginally overt. Facing straight on, he painted Pandora's box as female genitalia, as a casket with oval carvings, complete with evil vulval vapours being emitted from the genital cleft (see Figure 5.2). This extraordinary drawing also depicts Pandora's vessel with handles resembling Fallopian tubes, and a base ridged like the muscular interior of the vagina.

The inside view

So what is the inside story? Thankfully, although myth may tell of a mouth with sharp dentition, ready to snap up and spit out unwelcome intruders, or a male vision of fear and hell, science has something else to say about what lies within the vaginal walls. After centuries of misunderstanding the vagina, of either ignoring it or calling it variously a royal highway, a passive vessel, and even essentially devoid of sensitivity, a new view is emerging. First of all, there are no teeth, snakes or dragons. And unlike the empty, dead space envisaged by early thinkers, the interior of the vagina is anything but a passive black hole. Instead, science reveals an amazing, expanding, contracting, sensitive muscular organ, where mul-

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

tiple erogenous zones rub shoulders with a remarkably robust pathogen defence system. In fact, flexibility or fluidity, not unyielding dentition, is the vagina s key design concept.

Have you ever considered that a woman's vagina is teeming and overflowing with life? Or that a veritable biological soup thrives here in this exquisitely balanced environment? Maybe not, but this is, in fact, the scenario inside female genitalia. Why should this be? The answer lies in what the vagina represents. Just like the mouth, or any open orifice, the vagina provides potential pathogens (disease-causing agents) with an avenue to the interior of the body. Moreover, the vaginal gateway heads the route to the rest of a female's reproductive organs, the crown jewels of a species' survival. It's not surprising, therefore, that like the mouth, with its super salival defence system, backed up by mucous membranes and tonsils and teeth, the vagina too has a very potent protection structure in place. But that is not all. The vagina is not just about defending against disease. It has another crucial and yet distinct role - enabling access to some, but not all, intruders. Depending on the situation, a woman's vagina needs to be capable of acting as both bodyguard and bouncer. To be able to perform in this perfectly poised, polar manner, the vaginal interior, or lumen, needs a wondrous environment. Snakes or sharp teeth are not the answer. On the contrary, the vaginal solution is a wet, moist and fluid one.

The joys of mucus

Mucus is the vagina's major medium. Defined as a protective secretion, mucus is the means by which the vaginal interior maintains its integrity in the face of all comers. Without the never-ending exuding of fluids, the vagina would not able to function effectively. For not only does mucus provide lubrication during sexual activity, it also acts as a selective barrier against pathogens, and supports a cornucopia of essential organisms. Yet despite its indispensability, mucus, more often than not, gets a bad name. Slimy, gloopy, gummy, oozing from clefts and crevices, the nasal brand is tarred with the slang word 'snot' while the vaginal variety suffers with the useless, demeaning designation of 'discharge'. In many cultures, vaginal discharge equals dirt, often translating as such in language. Moist, wet, well-lubricated genitals are viewed by some as disgusting, polluting and to be avoided.

In some central and southern African countries, a dry vagina is promoted as the genitalic gold standard - as rated by men. Women use concoctions of salts and herbs in a bid to fulfil this strange male desire for an arid vagina. One study of intravaginal practices in Zimbabwe revealed that more than 85 per cent of women have used drying salts at

THE STORY OF V

least once. Horrifically, however, the dry sex that men are said to crave leads inevitably to chafing and cracking of the vaginal walls, leaving women at risk of infection. As previously noted, it is now recognised that it is only when there are abrasions or damage to the mucosal lining of the vagina that viruses, such as HIV, can infect a woman. That is, if there is no damage to the vaginal wall, infection cannot occur as immune cells are not exposed to the virus. Zimbabwe, frighteningly, has one of the world's highest rates of HIV infection, a fact which is without doubt in part explained by the craze for moistureless sex.

However, there is another very disturbing aspect here. Many, if not all, vaginal contraceptives actually contain chemicals, such as nonoxynol-9, that damage the mucosal layer of the vagina, leaving it open to infection. It seems astoundingly bad science to me that this situation exists, that a chemical that damages female genitalia can be used as a common vaginal contraceptive. What's more, the appalling fact is that nonoxynol-9 is the major ingredient of such contraceptives as contraceptive jelly. When used in conjunction with a diaphragm, nonoxynol-9 is placed in direct contact with the cervix, which is even more easily damaged than the vagina. This is because cervical cells are extremely thin (only one cell thick), fragile and easily damaged. If nonoxynol-9 damages the vaginal cell wall, which is far more dense, sturdy and resilient than the cervix (the surface layer of squamous epithelium vaginal cells is up to 16-30 cells deep), then what level of damage is nonoxynol-9 doing to the cervix? In my own experience, using a diaphragm and contraceptive jelly with the major ingredient nonoxynol-9 led to regular cervical bleeding and severe abrasion to the cervix. When I stopped placing nonoxynol-9 in direct regular contact with my cervix, the bleeding stopped and the abrasions healed.

But back to mucus. Importantly, there is no one fount of female mucus. Instead, female fluids well up and flow from a variety of vaginal sources, coming together to form a cocktail of secretions. Both external and internal genitalia contribute. In the mix are fluids from the Bartholin's (or major vestibular) glands, which sit at five and seven o'clock to the entrance to the vagina, as well as those from the nearby minor vestibular glands. A woman's prostate gland (sometimes called Skene's or paraurethral glands) also furnishes fluids, as do the vaginal walls, both as a result of sexual arousal and as vaginal wall cells are shed. Mucus cascading cyclically from a woman's cervix coalesces with fluids from the uterus and Fallopian tubes above. Cervical mucus comes in columnar flows and together with uterine or endometrial secretions, is the major ingredient of female mucus. However, secretions from the sweat glands and oil-producing sebaceous glands situated in the smooth, glossy skin of a woman's inner labia also blend in, as does mucus from newly discovered

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

interlabial glands, about which very little is yet known. The end result is a potent, heady and dynamic brew.

One of the reasons why the precise number and nature of the constituents of vaginal mucus is as yet unclear is the lack of research done in this area. However, there are thousands of micro-organisms thriving in this flora. Mucus is plump full of them. Among them are sugars, proteins, acids of all sorts, simple and complex alcohols, bacteria and antibodies. All these molecules and many more as yet unidentified flow into and are supported by the vagina's mucoid environment. This bountiful fluid is also in continual flux, depending on a woman's menstrual cycle, her sexual arousal and activity, her physical and mental well-being, even the food she eats. In many ways, a woman's vaginal mucus is a barometer of herself and her lifestyle.

For many mucosal compounds, the major role appears to be one of defence, of making sure that this warm, moist ecosystem does not become a haven for disease. Indeed, it is argued that female genitals have their own separate immune system, courtesy of mucosal secretions. Mucus protects in a variety of manners, not least by lubricating vaginal tissues. This viscous moving fluid acts as a physical barrier as its continual slow flow down and out of the vagina prevents micro-organisms from attaching to the cell walls of a woman's vagina. It can also block indirectly, by providing bacteria with a false receptor or target to bind to.

Female genital mucus also supports an ace team of defensive agents. This mucosal posse includes molecules such as lysozyme, which punctures bacterial cell walls; lactoferrin, which mops up the iron that some micro-organisms need to grow; several classes of virus-neutralising antibodies; defensins or antimicrobial peptides; and phagocytic cells, which can engulf and swallow all intruders, including sperm. One cervically produced antibody, secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA), works like a killer sheepdog - rounding bacterial particles up into one coherent mass, and then preparing them for ingestion and digestion by phagocytic cells. Another cervical fluid constituent - a protein called secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) - has been shown to play a critical role in wound healing by reversing tissue damage and hastening healing. Its uses seem manifold - with evidence suggesting that it has anti-inflammatory, antifungal, anti-bacterial and anti-viral properties.

The need for a tart vagina

Curiously, centuries ago vaginal pH was thought to be important in determining the sex of any child conceived - acid (low pH) for a boy, alkaline (high pH) for a girl. Sadly, this is an ancient scientific theory that has yet to be proven. However, vaginal pH is of vital importance for

THE STORY OF V

women, but its significance lies in ensuring a healthy vagina. In fact, maintaining vaginal pH is an important way in which some organisms within vaginal mucus keep potential pathogens at bay. In the healthy premenopausal woman, vaginal pH should remain low, hovering around pH 4.0. That is, it's best to be acidic, or tart, but not as tart as a lemon (pH 2.0). More like a glass of good red wine. Keeping to this level of acidity is key because it determines a 'healthy' balance of vaginal microorganisms, or flora, in vaginal mucus. That is, an acidic vagina keeps numbers or ratios of micro-organisms in check. In contrast, a too alkaline environment tends to result in an overabundance of some micro-organisms, which can then become pathogenic (disease-causing) agents. Low pH is also good for the cervix, as it protects the extremely thin and fragile cervical cells from damage.

Quirkily, the guardians of low vaginal pH are a particular type of bacteria, lactobacilli, which occur naturally in the vagina. This may seem surprising, as bacteria are a type of micro-organism that often get a bad name. In fact, when first discovered at the end of the nineteenth century, the many varieties of vaginal bacteria were incorrectly viewed as unclean, disease-causing agents. But bacteria, be they the vaginal variety or not, do not deserve their negative press. As with many things in life, striking the right balance is what is important, and this is true for all types of bacteria too. Too few vaginal lactobacilli can result in a rise in pH to alkaline levels, and the flourishing of micro-organisms (with their increased numbers making them potentially pathogenic). Crucially, the best way for a woman to keep her lactobacilli at the healthiest levels is to lead as healthy a lifestyle as possible. That's all you have to do, and your vagina will do the rest naturally. However, dousing the vagina in man-made chemicals, such as those contained in so-called vaginal douches, deodorants and wipes, is not recommended ever, as this removes the vagina's natural defences.

Sperm bodyguard and bouncer

The story of what happens to sperm inside female genitalia highlights how vital a woman's vaginal environment is. This is because having an acidic vagina is critical in removing unwanted or surplus sperm. For human sperm, the vagina represents an extremely hostile and lethal environment, and prolonged sperm survival is not possible under these selectively acidic conditions (twenty minutes is the maximum). Out of the sixty million or more sperm contained in one human ejaculate, most will die in the vagina. The buffering or balancing effects of seminal plasma (the medium in which ejaculated sperm are suspended) offers some protection to sperm against the acidic conditions in which they find themselves. However, its effects are limited - following sperm ejaculation in the

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

vagina, vaginal pH rises to between pH 5.5 and pH 7.0, but this shift to a more sperm-friendly flora is transient. Within at least two hours, a legion of lactobacilli will have tipped vaginal pH back in the female's favour.

Once deposited in the vagina, if human sperm are not killed by the acidic conditions, engulfed and eaten by marauding phagocytic cells or simply ejected by the woman, they face another challenge - cervical mucus. Produced primarily by glands in the top half of the cervix, cervical mucus creates a dense mucoid plug which essentially fills the uterine cervix. And from there columns of mucus cascade ceaselessly down into the vagina, averaging around 20-60 mg a day. This cervical mucus has a crucial reproductive role - namely, acting as a very effective biological barrier, or sperm bouncer.

When faced with this mucus, sperm have a problem. It seems they are incapable of passing through, round, over or under this formidable mucoid material. They have met their match, and the next stage underlines this. Unable to overcome this viscous hurdle, sperm are then swept out of the vagina, escorted off the premises by the slow, unstoppable flow of bouncer cervical mucus. There is, however, one sticking point in this scenario. Cervical mucus is mercurial, and does not always act as a sperm bouncer. In fact, on some days of the month, cervical mucus undergoes a compete role reversal, metamorphosing, dramatically, into a sperm bodyguard.

For just a few days every month - typically from about two to three days prior to ovulation, and up to twenty-four hours post-ovulation -cervical mucus becomes sperm's major ally in its fertilisation quest. While other elements of the vaginal environment rush to repel the newcomers, bodyguard mucus moves to embrace them. The difference between bouncer mucus and mid-cycle bodyguard mucus is immediately apparent in other ways too. Visually the change in consistency, sheen and colour is stunning. What was an opaque milky-white glutinous fluid mass of limited elasticity (maximum extended length about 2.5 cm) transforms into a glistening, translucent, silky and seemingly endlessly stretchy amorphous substance (some say it's like egg white). Mucus columns of between 7 and 10 cm in length are not uncommon.

This extreme stretchiness of mid-cycle mucus is one of its key characteristics, and, indeed, has given rise to the term 'spinnbarkeit' - that is, the capacity of cervical mucus to elongate. Another feature (noted by scientists) is that this fertile mucus forms a fern pattern when dried. This is because of its high salt content. However, for women monitoring their fertility, the point to remember is that the more stretchy and akin to egg white the mucus, the closer you are to ovulating. Another thing to look out for is that production is scaled up too. At mid-cycle, ten times more mucus - 600 mg - streams forth daily. This increased mucus flow pre-

THE STORY OF V

ceding egg release is also accompanied by changes in a woman's cervix. The external os (mouth) opens up to around 4 mm in diameter between twenty-four and forty-eight hours before ovulation - a move that is believed to enhance the likelihood of conception occurring.

Research shows that mid-cycle bodyguard mucus can both shepherd and shelter sperm, offering a safe passage out of the vagina through the cervix and into the uterus, as well as a safe alkaline harbour. If sperm are lucky enough to land near a column of mid-cycle mucus, they appear to be sucked inside the mucus structure. And when enveloped in these mucus arms, genital contractions are believed to draw sperm nestled in their mucus environment up into the cervix and uterus. Incredibly, it seems that cervical mucus can support human sperm for prolonged periods of time, as research shows that sperm sequestered in folds of cervical mucus, or cervical crypts, can survive, remaining motile, for between five and eight days (uterine fluids may also play a role in this support).

It's now appreciated that fluctuations in the levels of circulating hormones are the driving force behind the physical changes in mucus which make bouncer mucus impenetrable to sperm, and result in bodyguard mucus drawing sperm passively in. Increasing levels of oestrogen in the days preceding ovulation result in the structure of cervical mucus becoming one of parallel filaments of long mucin molecules, with canals in between along which sperm can travel. However, post-ovulation, increasing levels of progesterone disrupt this ordered structure, and the filaments form a criss-cross matrix through which sperm cannot traverse.

Mid-cycle bodyguard mucus also has another vital reproduction role to play. And this time it's a selective one. The microstructure of mucus reveals how this selection could function. Critically, the canals or channels separating one parallel mucus section from another are extremely thin. At between 0.5 and 0.8 jum they are smaller than a sperm head, making any movement through this mucus a very tight squeeze for sperm. Indeed, experiments with human mucus show it bulging and stretching around sperm. However, the precise importance of forcing sperm to be in such close proximity to cervical mucus is as yet uncertain.

One intriguing idea is that this extreme proximity forces necessary interactions between mucus and sperm, perhaps preparing sperm for fertilisation by shearing certain seminal components from their surfaces. Recognition is another exciting suggestion, as it is known that this enforced closeness does play a sperm-screening role, with mid-cycle cervical mucus acting as a biological filter, sorting the normally shaped sperm from the morphologically abnormal ones. However, recognition may involve far more than just sorting shapes; selecting a complementary genetic partner may also form part of cervical mucus' multiple functions.

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

Scientists are just at the start of understanding how the female genital tract as a whole, including mucus, selects a female's Mr Right Sperm.

Reading the vagina

Penis size, it is said, is a prime concern for many, if not all, men. And this male obsession with genital size is not, it seems, confined to the phallus. Around the world, estimating and classifying vaginal size and attempting to map out the internal contours of the vagina has proved to be irresistible to men, often with eye-opening and entertaining results. In the west, the desire to put a name to a woman's genital landmarks has led to some wonderful medical monickers. There's 'the fold of Shaw', 'the pouch of Douglas', 'the column rugarum', 'the hollow of modesty', 'the canal of Nuck' and 'the elastic sac of Sappey'. These titles were, of course, all bestowed and imposed by men. Today they seem ridiculous, and are, in the main, obsolete.

Outside the west, Arabic, Indian, Japanese and Chinese cultures provide beautifully detailed and inventive information on the interior of the vagina, and how it has been perceived. For example, the Arabic erotic manual, The Perfumed Garden, written by Sheikh Nefzaoui, details thirty-eight varieties of vagina, and thirty-five types of penis. Vaginal descriptions include, el aride, 'the large one' - a thick and fleshy vagina; el harrab, 'the fugitive' - a small and tight vagina that is also short; and el mokaour, 'the bottomless', a name referring to a deep vagina, one that is lengthier than usual. The possessor of this larger vagina, The Perfumed Garden points out, needs a particular partner or position to truly arouse and satisfy her fully.

Ancient Japanese culture, in the sacred text The Sutra of Secret Bliss, also describes differently sized vaginas, associating them with one of the recognised five elements of life - earth, water, fire, air and ether (heaven). The Daikoku is the dark earth vagina, one that envelops and holds the penis; the Mizu-tembo is the moist water vagina, with a small opening and a wide interior, while the Bon-tembo is the celestial vagina - most beautiful and fragrant. This variety of vagina is also known as the Dragon's Pearl, because its tight opening and narrow passage lead to a pearl-like womb. Poetically, it is said that anyone fortunate enough to enter a vagina like this cries out in ecstasy.

India's famous sex manual, the Kama Sutra, provides a particularly detailed look at both sexes' genitals. This book, depicting the erotic science of ancient Indian culture, arranged women and men in terms of their sexual characteristics. That is, classifying them by the size of their genitalia, their force of passion or carnal desire and 'their moment of sexual impulse' (the time factor). For women, this classification, which was

THE STORY OF V

written by men, results in four orders, three "temperaments and three kinds. Each of these ten categories describes the characteristics of the particular vagina, and the Kama Sutra also gives advice on the sexual compatibility of women and men in terms of their sexual characteristics. Vaginal length or depth is revealed by the three kinds of women, and is as follows:

1) The tnigri (female gazelle) or harini (doe) is the woman with a deep-set vagina (six fingers deep) that is cool as the moon and has the pleasant scent of a lotus flower.

2) The vadama or ashvini (mare) is the woman with a vagina nine fingers deep, with freely flowing yellow juices and the scent of sesame.

3) The karini (she-elephant) is the woman with a vagina twelve fingers deep with abundant juices that smell like elephant's musk.

Mesmerisingly, many other methods of describing or classifying the vagina exist. Tantric texts divide the vagina into six regions governed by different Indian goddesses - Kali, Tara, Chinnamasta, Matangi, Lakshmi and Sodasi. Meanwhile some eastern texts describe the lower vulval portion of a woman's vagina as having the following four properties: 'First, it looks like the tip of an elephant's trunk; second, it is twisted, like the turns on a shell; third, it is closed up, as if by something soft; and fourth, it opens and closes like a lotus flower.'

If you want to read the vagina, there is also the option of using the ancient Chinese art of reflexology. Using this viewpoint, the lower third of the vagina and the vaginal opening correspond to the kidneys, the central third the liver, and the uppermost third of the vaginal chamber the spleen and pancreas. The cervix, meanwhile, corresponds to the heart and lungs. This way of looking at the vagina also stresses the importance of stimulating each portion of female genitalia - from the kidneys up to the heart and lungs - shallowly and deeply and circling from side to side if a woman is to be truly satisfied and sexually energised. It sounds good to me.

The Palace of Delight

Looking at the various systems employed over the centuries to classify and understand the interior of the vagina, it's hard not to get the feeling that genital measurement isn't perhaps a particular male metier, as some vaginal dimensions are somewhat startling. Chinese sexual manuals, such as the Taoist text The Wondrous Discourse of Su Mi, detail how vaginas come in eight different varieties - each determined by the depth of the vaginal interior, and each 2.5 cm longer than the previous. However,

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

some, such as the Zither String, seem surprisingly short, while others, like the North Pole, are somewhat on the lengthy side. In ascending size, the Eight Valleys, as they are known, are:

1) The Zither String or Lute String (ch'in-hsien), 0-2.5 cm

2) The Water-caltrop Teeth or Water-chestnut Teeth (ling-ch'ih), 5 cm

3) The Peaceful Valley or Little Stream {fo-hsi), 7.5 cm

4) The Dark Pearl or Mysterious Pearl (hsiian-chu), 10 cm

5) The Valley Seed or Valley Proper (ku-shih), 12.5 cm

6) The Palace of Delight or Deep Chamber (yu-ch'ueh), 15 cm

7) The Inner Door or Gate of Prosperity {k'un-hu), 17.5 cm

8) The North Pole {pei-chi), 20 cm

Chinese sexual manuals also classified the relative position of the vulva -be it high (in a forward/upward location), that is, placed more ventrally or towards the belly, to the middle, or low (lower on the perineum).

So what is the average length of the vagina? Importantly, what the above ancient measurements do not articulate is that the interior of the vagina cannot be calibrated in this way - with just one length. For every woman, the ventral or anterior wall of her vagina - the belly side - is shorter than the opposing, posterior, wall (adjacent to the rectum). This is because the cervix, which sits at the apex of the vagina, projects down into the vagina, making the ventral vaginal wall shorter than the other. (The twin arch-like spaces that are created between the vagina wall and the curving cervix are known as the anterior and posterior fornices -singular, fornix - a word that is said to derive from the habit in Roman times of prostitutes renting vaulted or arched basements for them and their clients to fornicate in - the Latin word for arch being fornix).

And the average length from vaginal entrance to fornix and cervix? Most recently, average vaginal length (when not sexually aroused) has been placed anywhere between 7 and 12.5 cm, with the posterior length of the vagina from 1.5 to 3.5 cm longer than the ventral vaginal wall. Importantly, just as all penises vary enormously in size, so too do all vaginas. There is no standard. And just as all penises lengthen when aroused and erect, so too do all vaginas, as we shall see.

The fabulous shape-shifter

While all women have an intrinsic vaginal size, vaginal structure and volume can be altered. The key characteristic of the vagina is, after all, flexibility. And this flexibility in shape derives from the fact that the vagina is, in essence, a fibromuscular tube. Strategically placed muscles encircle and form its length and breadth. Hence the vagina can constrict or be

THE STORY OF V

constricted, dilate and change internal pressure. In fact, courtesy of her richly innervated and sensitive genital musculature, a woman's vagina is anything but a passive, unresponsive organ. This fact is demonstrated remarkably eloquently by the miracle of childbirth.

Mind-blowingly and eye-wateringly, the vagina expands to at least ten times its normal size during the delivery of a typical bouncing baby. The cervix, too, must dilate to a great degree, becoming as wide as the vagina is long. For the cervix, this amazing feat of distension can only be achieved by the prior softening of cervical tissue, and results in a permanent visual record of childbirth. In a woman who has not experienced childbirth via vaginal delivery, the os, the extremely slim opening of the cervix to the uterus, appears as a small dimple in the middle of the circular cervix. After vaginal delivery, this indentation takes on a special character, like the upward curve of a smile, or the wink of an eye, if you will. A smiling, winking cervix is the sure sign of a woman who has brought a child into the world vaginally.

The fantastic flexible nature of the vagina is also immediately obvious during sexual arousal and intercourse - a fact that was recognised and appreciated by western men of science over three hundred years ago. While Reinier de Graaf reckoned the vagina to be '6, 7, 8 or 9 finger-breadths long', he also observed in his pioneering work The Generative Organs of Women that: 'During coitus it applies itself everywhere to the penis and accommodates itself along every dimension in such a way that its concave shape becomes one with the convex shape of the penis ... During childbirth it adopts yet another shape ...' De Graaf was also quite astute in noting that it was sexual arousal that had a strong effect, commenting how 'during coitus it shortens, lengthens, constricts and dilates more or less according to the degree of the woman's excitement'. Delightfully, under the chapter heading ' Concerning the Vagina of the Uterus', the Dutchman enthuses, rhapsodises even, how:

The woman's vagina in fact is so cleverly constructed that it will accommodate itself to each and every penis; it will go out to meet a short one, retire before a long one, dilate for a fat one, and constrict for a thin one. Nature has taken account of every variety of penis and so there is no need solicitously to seek a scabbard the same size as your knife... Every man can thus come together with every woman and every woman with every man, if there is compatibility in other respects ...

The importance of females possessing powerful shape-changing genitalic musculature is highlighted by the ways in which a vast array of other species use their vaginal muscles, in particular to improve their reproductive success. Female hyaenas, as we've seen, need pelvic muscles robust

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

enough to retract their elongated clitoris back to create an internal vagina. Many insects have vaginal (bursa) muscles steely enough that they can prevent copulation occurring or force out an unwanted member. The vaginal muscles of honey bees are thought to be responsible for triggering the male's ejaculation, while the male marsh-dwelling bug, Hebrus pus-illus, must rely on the strong milking action of the female's genital muscles to suck sperm from his phallus. Genital musculature also underlies the routeing of sperm to storage or disposal sites, or ovaries, in many insect species.

Muscles, muscles, muscles

The effects of possessing strong vaginal muscles can be just as stunning in humans. Today, fine vaginal muscle control is most directly in evidence within the shows of the sex industry. Smoking cigarettes, firing ping pong balls, writing messages, opening bottles, even picking up sushi with chopsticks - vaginas can perform all these feats and more. However, while these cunning stunts may be financially rewarding for women and titillating for men, the human vagina's impressive muscularity was not designed with bottles, balls and cigarettes in mind.

It is in the ancient teachings of eastern cultures that another, more sensual and mutually pleasure-oriented role is seen for a woman's vaginal muscles. Pompoir (a Tamil term) or bhaga asana (from the Sanskrit) are two of the names given to the vaginal technique of embracing and locking the penis and keeping it in a prolonged erection by means of the vaginal musculature alone. For men, pompoir is an exercise in penile passivity, as all that moves is the vaginal muscles. Using the pelvic floor muscles in this way has been seen for centuries as a way of enhancing sexual pleasure for both partners and controlling sexual timing. It is also enjoyed as an intensely pleasurable means of self-stimulation by women, and it is in this particular pose that a famous statue of the Indian goddess Kameshvari is thought to be sitting in the town of Bheraghat.

In the sixteenth-century Indian erotic manual the Ananga Ranga, written by Kalyanamalla, a woman who has mastered the sexual and pleasure potential of her pelvic muscles is known as a kabbazah, which is an Arabic word meaning 'holder' or 'clasp'. The 1885 translation of the Ananga Ranga, by Richard Burton, describes the muscular art of the kabbazah and pompoir as follows:

This is the most sought-after feminine response of all. She must close and constrict the yoni (vagina) until it holds the lingam (penis), as with a finger, opening and shutting at her pleasure, and finally acting as the hand of the Indian Gopala-girl, who milks the cow. This can be learned only by long

THE STORY OF V

practice, and especially by throwing the will into the part affected. Her husband will then value her above all women, nor would he exchange her for the most beautiful queen in the Three Worlds.

Even Islam's Muhammad is reported to have said: 'Allah made intercourse so pleasurable and attractive that it is imperative to enjoy sex fully with every nerve and muscle.'

The contractile vaginal talents of many women are described throughout history and literature. Ancient Greece's famous courtesans, the hetaira, are famed for being able to split a clay phallus with their vaginal muscles. This was a test of their genital strength and skill. Such talents are also among those ascribed to Diane de Poitiers (1499-1566), the mistress of King Henry II of France, to explain the fact that she was, shockingly to some, twenty years older than her royal partner. French author Gustave Flaubert enthuses about his encounters with the professional prostitutes exiled in the Egyptian town of Esneh: 'her cunt milking me was just like rolls of velvet -1 felt ferocious'. Across the globe, Shilihong was a Shanghai sex worker famed for her exceptional control of her vaginal muscles. She is said to have been able to move a man's penis in and out of her simply by contracting and relaxing her muscles, a movement that bestowed a sucking-like sensation. Wonderfully, the 'Shanghai squeeze' of Wallis Simpson is said to be one of the reasons why Britain lost a king in 1936. Mrs Simpson, it was noted, 'had the ability to make a matchstick feel like a Havana cigar'.

The importance of education

The erotic and sexual techniques of this muscular vaginal artistry are still to be found today - but only in those women who choose to train their vaginal muscles. In India, vaginal exercises are known as Sahajoli, and for some girls they are taught from childhood, first by their mother and later by a Tantric guru. Sahajoli also form part of the training of Devadasis, Indian temple dancers. Such vaginal exercises are practised by devotees of Tantric or sexual yoga, and are designed to enhance sexual pleasure. They include abdominal and pelvic flexes (mudra) as well as muscle locks (bandhas), and some, such as the Mula Bandha, can work for men too.

The ability to exercise vaginal muscle control is viewed as a key vaginal quality in Polynesia's Marquesan society. The Marquesans refer to vaginal contractions as naninani, and women who have the strength and staying power to retain control over multiple squeezes during repeated sex sessions are, not surprisingly, revered. Moreover, great emphasis is also placed on particular pelvic movements during sex, which, it is said, play a major part in the mutual pleasures of sexual intercourse. The Marquesan

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

term for this sensual pelvic motion is tamure, named for the Tahitian dance of the same name, which features movements resembling those of sexual intercourse.

Significantly, the capacity to move the pelvis in a particular way during sex is not the sole province of women. Marquesan men are expected to be able to roll with it too, and perhaps this is why sex commonly ends with the orgasms of both parties. Marquesan women apparently have no problems reaching orgasm, be it simultaneous or not. It's obvious that vaginal muscle control is one key to this orgasmic art (as is male participation), but sex education is also a vital factor. Tellingly, on reaching puberty, Marquesan girls and boys receive sexual instruction - girls from their grandmothers or women of their grandmothers' generation, and boys from an older woman. Their education involves positions, techniques of sexual stimulation and general sexual hygiene. Sadly, though, this way of educating appears to be on the decline.

The sexual heart

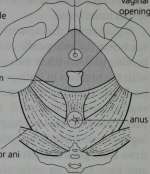

Considering the potential strength and dexterity of her vaginal embrace, it is not surprising to find that a woman's genital musculature is complex. Criss-crossing, encircling, embedding, pulling, grasping, tugging and pushing, together this muscular network enables all a female's internal pelvic organs - urethra, vagina, uterus and rectum - to remain in the right place, and perform all their functions. These muscles surround and penetrate the vaginal walls, tying the vagina into the pelvic structures. Three groups of muscles are today recognised as enclosing and surrounding the length of the vagina (see Figure 5.3 and Table 5.1). They are - in ascending order - the muscles of the perineal body (the small muscular mass that fits between the floor of the vagina and the rectum), the muscles of the urogenital diaphragm, and the muscles of the pelvic floor, or diaphragm.

These muscular groups effectively divide the vagina into three compartments - the upper, the area above the pelvic floor; the middle, which is encircled by muscles from both the pelvic floor and the urogenital diaphragm; and the lower, associated with the perineal body musculature. Interestingly, this division of the vagina into three areas as defined by muscle groups tallies with Taoist teachings on vaginal muscular control. When able to isolate and flex these groups of muscles at will, as a result of mastering Taoist sexual techniques, women are then able to move two small mineral eggs (2.5 cm in diameter) within their vagina in different directions, or bring them together with a bang.

Looking at the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, you can see that the Italian artist was fascinated by the musculature of the lower vagina, in

THE STORY OF V

bulb

suspensory ligament

vaginal opening

anus

urethra

schiocavernosus muscle

bulbospongiosus muscle

urogenital diaphragm

transverse perineal muscle

levator ani

levator an

anal sphincter N tailbone

Outer layer

bulb

inner lips

ischiocavernosus outer

muscle lips

levator ani

urogenital diaphragm

bulbospongiosus muscle

urethra

vaginal opening

Middle layer

urethra

vagina

levator ani

(the levator ani group of pelvic muscles

includes the pubococcygeus (PC) muscle

and the iliococcygeus)

Front view

Inner layer

Figure 5.3 A woman's vaginal musculature is impressive, complex and powerful, and comes in three distinct groups or layers. Use them, don't lose them.

particular the muscles of the perineal area. Amongst his numerous sketches of the human body are ones of the muscles around the anus, which focus on their circular petal-like external appearance. Tellingly, he called these muscles 'the gatekeeper of the castle'. Da Vinci's gatekeeper muscles of the perineal body include ones that support the vagina from side to side, others that constrict the anus, as Well as muscles that cover the crura or legs of the clitoris and one that covers the vestibular bulbs. This latter muscle also loops round and surrounds the vaginal opening, and when

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

Table 5.1 Vaginal Musculature

Perineal body • anal constrictors ('the gatekeepers of the castle')

• superficial transverse (provide support from side to side)

• bulbospongiosus or musculus constrictor cunni, covers the vestibular bulbs and surrounds the vaginal opening

• ischiocavernosus - the clitoral muscles

Urogenital diaphragm • deep transverse perineal muscle (provides support from side to side)

• constrictor of the urethra (sphincter urethrae)

Pelvic floor • pubococcygeus (PC), runs from the pubic bone

to the coccyx. Part of the PC is known as the puborectalis.

• iliococcygeus (IC)

• coccygeus ( ischiococcygeus)

Together the PC, the IC and the urethral and rectal muscles are known as the levator ani group (meaning literally 'to raise the anus'). The bulbospongiosus muscle is sometimes referred to as the bulbocavernosus.

Adapted from Lowndes Sevely, Josephine, Eve's Secrets: A New Theory of Female Sexuality, New York: Random House, 1987.

contracted, constricts the lower vagina, in particular making the opening of the vagina smaller. It is now known as the bulbospongiosus muscle, but was previously called the musculus constrictor cunni, for obvious reasons. The clitoral muscles (the ischiocavernosus muscles) also alter on arousal, contracting as the clitoris fills with blood and becomes erect. This movement pulls the clitoris into closer contact with the vagina, and is seen as the crown of the clitoris raises, typically arching back under the clitoral hood. Above the perineal body are the muscles of the urogenital diaphragm - which again support the vagina from side to side, and also constrict the urethra.

The group of muscles known as the pelvic floor, or diaphragm, is the set that has received the most public attention. This is the muscle group that women are recommended to exercise post-childbirth or to help with sexual arousal or incontinence problems. As a group, the pelvic floor forms a sheet of muscle slung intimately round the middle section of the pelvic organs. A side view reveals the funnel or cone-shaped structure. The most famous pelvic floor muscle is the pubococcygeus muscle, PC for short. Its name reveals where it runs from - the pubic bone - and where it runs to - the coccyx, the tail end of the spine. In animals, the PC muscle

THE STORY OF V

is the one that wags the tail. The PC muscle, together with the other pelvic muscles in this group, act to support the pelvic organs (the urethra, vagina and rectum in women), and also assist in maintaining continence when bouts of coughing, sneezing or muscular activity raise intra-abdominal pressure. During pregnancy, the pelvic floor group must also support the combined weight of the uterus and the unborn child.

While the PC muscle is a principal player in the pelvic floor grouping, it does not act alone. Rather it works in glorious concert with its surrounding group of muscles and those adjoining. Together a woman's genital muscles orchestrate the delicate caressing or harder grasping action of the vaginal chamber. The rhythm goes something like this. As the PC muscle contracts, another portion of the pelvic floor muscle, the closely related puborectalis, contracts too. Together the effect is to narrow, elongate and partially straighten the lower two thirds of the vagina. As this happens the upper part of the vagina, including the fornices (arches) around the cervix, widens and balloons, with a resultant lowering of pressure. Closer to the vaginal entrance, the bulbospongiosus muscle also contracts. Because this muscle encircles the vaginal entrance, vaginal pressure in the lower third is higher than in the middle third - and the pressure in the middle third is higher than that of the upper. Taken as a muscular whole, with its three distinct groupings of muscles clasping, contracting and expanding, it is not too difficult to understand why the vagina has been described as a sexual heart. Or to envisage the vagina effectively milking the phallus with a grasping, pulsing grip.

Use it, dont lose it

Disappointingly, though, decades of leading a sedentary lifestyle, sitting and slouching on the closest easy chair or sofa, instead of squatting on your haunches, means that for many people - women and men alike, and not just post-childbirth - their pelvic muscles are slack. Like any other muscle, if you don't use it, you'll lose it. However, just as the muscle mass of an individual's biceps or pectorals can be strengthened and sculpted as a result of regular exercise, so too can a person's pelvic muscles. The result of such exercise is an organ with exquisite muscle control.

There are also health benefits. In both sexes improved strength and control of the pelvic floor muscles results in improved urinary and faecal continence. Levels of sexual arousal and performance are enhanced too. Indeed, for many women, simply contracting and relaxing their vaginal muscles if they are strong enough is sufficient to trigger orgasm. In men, improving pelvic muscle strength has been shown to reverse a diagnosis of impotence. In women, research shows that the strength of a woman's pelvic muscles ranges from 2 or 3 microvolts to 20 or 30. On average,

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

women can produce a 9-10 microvolt contraction; however, below the average stress and urge incontinence are increasingly more likely. But above the average, women can look forward to an increasing likelihood of multiple orgasms in proportion to muscle strength.

A word of caution should be sounded, though, regarding the practice of exercising pelvic muscles. Learning to work a muscular group can be tricky, not least because most women are unable to see their own muscles move. Kegel exercises are often recommended for women. However, the original pelvic floor exercises, as devised by Californian gynaecologist Dr Arnold Kegel in 1951, are markedly different from those typically promoted today. Kegel's original workout involved the insertion of a resistive and compressible device inside the vagina. Contraction of the pelvic floor muscles resulted in a reduction in volume of the resistive device which was shown as a pressure reading on an external handheld meter. This was the Kegel perineometer. Only in this way, Kegel reasoned -by providing resistance to work against and some form of feedback about what was happening internally - could women increase their awareness of their pelvic floor muscles, and appreciate and enjoy the muscles' gain in strength. Kegel even made casts of vaginas, called mulages, to illustrate the effects of diligent use of his perineometer. This Kegel perineometer, it is argued, was the world's first biofeedback device.

Today, electronic biofeedback instruments or a specialised physiotherapist can help those with particularly weak pelvic muscles. Regular exercise with a readable resistive device is also recommended - or try a partner's penis. However, the simple squeeze against nothing routines that bear Kegel's name are not as effective. They provide neither resistance to work against or any feedback on what is happening, i.e., is it working and am I improving? All too often a different muscle group is flexed too, or the right muscle group is contracted but not relaxed properly, which can lead to chronic pelvic tension and persistent pain.

The shape of things to come

Flexing the vagina's muscles is integral to sexual arousal because this simple action can reroute circulating blood, pulling it rapidly into the capillaries of the surrounding vaginal walls. This increase in blood flow causes the walls to billow with blood, and their blood volume increases too. This is vasocongestion (vaso - denoting blood) of the vaginal walls. Vaginal vasocongestion then has two knock-on effects on a woman's vaginal walls - they lubricate and they lengthen. Lubrication first. Associations between the vagina, sexual arousal and wetness have existed for many years - the inner lips of the vagina were known since the first century as nymphae - water goddesses in Greek - while in ancient Greek

THE STORY OF V

comedies, male actors playing female roles wore bags of fluid to denote genital excitement. In Japan, the word for sexual intercourse is nure, meaning to grow wet.

However, despite this history, in particular an accurate description by Reinier de Graaf in 1672, the idea that the walls of a woman's vagina exuded fluid during sexual arousal was not widely accepted until over three hundred years later. Viewpoints only began to change when William Masters wrote his seminal paper, 'The Sexual Response of the Human Female: Vaginal Lubrication in 1959. Masters noted that as sexual excitement rose, as a result of either physical or mental activity, a 'sweating' reaction occurred on the surface of the vaginal walls.

Individual droplets of a lubricating material suddenly appear scattered over the rugal folds of the normal vaginal architecture. These individual droplets present a picture somewhat akin to that of a perspiration-beaded forehead. With continued increase of sexual tension the droplets coalesce to form a smooth, glistening coating for the entire vaginal wall. This sweating reaction progresses to establish complete vaginal lubrication early in the excitement phase of the human female's sexual response cycle.

Significantly, the vaginal wall lubrication reaction is an incredibly rapid one. The lubricating fluid, or transudate, can appear between ten and thirty seconds after the initial perception of sexual excitement, but can disappear as rapidly if excitement does too. It's now recognised that the production of this lubricating fluid is a result of the vaginal walls becoming thickened and engorged with blood. However, it should be said that sexual arousal is not the only method of production. Many kinds of muscular activity, if they bring the pelvic muscles into play, have this lubricating effect. I know that a Saturday morning wake-up work-out at the gym will always result in increased levels of vaginal lubrication. At the end of such a session, I am most definitely not sexually excited, but I am very physically aroused and wet - from both sweat and vagina juices. How a woman's vaginal walls lengthen during sexual arousal and intercourse is a topic that has also only recently been fully appreciated -visually, that is. Experiments in the 1960s by Masters and Virginia Johnson suggested that the walls of the vagina enlarged during sexual excitement. Unfortunately, the fact that they used an artificial penis to achieve this effect was said to mar the legitimacy of their observations. Ultrasound experiments in the early 1990s also pointed to the vaginal walls growing in size, in particular the anterior (stomach-side) wall. However, it wasn't until the turn of the twentieth century that Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provided the first clear pictures of the shape-changing nature of the vagina. MRI gives a snapshot, or dynamic image, of a person's insides,

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

including their soft tissues, and as it is also non-invasive, to the extent that probes and monitors are not placed inside the vagina, it can be said to be the truest representation to date of how sexual arousal and intercourse affects the vagina. Only a handful of studies have so far been conducted, but these highlight the vagina's extreme flexibility and erectile capacity. One experiment recorded anterior vaginal length leaping from 7.5 cm in the non-excited state to 15 cm when aroused, a 50 per cent increase - quite impressive. Posterior vaginal length grew too, expanding from 11 cm to between 13 and 15 cm. In comparison, vaginal length in chimpanzees is estimated to be around 12.6 cm when unaroused, but leaps to 16.9 cm during arousal, and with external sexual skin fully swollen.

Importantly, increased vaginal lubrication and length are not the only internal changes that can be felt in female genital tissue during sexual arousal. The erectile tissue surrounding the urethra - the spongiosum -transforms too, becoming engorged with blood at heightened levels of sexual excitement (this is the same type of erectile tissue that surrounds a male's urethra). In a woman, the urethra is typically between 3 and 4 cm long, and runs from the neck of the bladder to the urethral glans -the point where the urethra exits the body, below the clitoris and just above the vaginal opening. The erectile spongiosum or urethral tissue completely encircles the urinary passageway and runs its entire length. In breadth, it measures between 2.5 and 3.5 cm, and is slightly thicker towards the neck of the bladder, and thinner towards the glans.

When a woman is aroused, the swelling of the spongiosum can be felt through the anterior or ventral (stomach) wall of the vagina. This is possible because of the very close relationship between the erectile urethral tissue and the ventral vaginal wall. The lower edge of the urethral glans defines the upper opening of the vagina, while the base of the urethral tissue comprises part of the ventral vaginal wall. Indeed, it could be said that the urethra and its surrounding spongy erectile tissue and musculature are inseparable from the vagina because the floor of the urethra is the ceiling of the vagina.

Hair pins for girls, bullets for boys

Just as the spongiosum tissue surrounding a man's urethra is erotically sensitive to pressure changes (such as those of a clasping hand or vagina), so too is a female's corresponding urethral tissue. Many women experience intense pleasure from stimulation of their urethra - either indirectly, via the ventral vaginal wall, or directly, by touching the urethral glans. A woman's glans and carina (the lower edge of the glans) is incredibly sensitive, and careful caressing can be just as arousing for women as it

THE STORY OF V

can for men. The rubbing of a man's corona over a woman's carina, as part of very shallow gentle thrusting, is a particularly intense and erotic sensation for many women. Some women also enjoy the sensations of internal urethral stimulation - although it should be said that extreme caution is advised here. Items such as hair pins have been lost in the ecstasy of orgasm, ending up in the bladder, with possible serious health consequences. Medical history also records the case of a man who chose to indulge in urethral stimulation with a rifle bullet - which also ended Up in his bladder.

Although the erotic potential of female urethral tissue was understood by many individuals as an integral part of their sexual geography, it wasn't until the middle of the twentieth century that such sensations were noted by the academic community. The person who pointed this out - Ernst Grafenberg - was a very forward- and free-thinking gynaecologist. Born in 1881, Grafenberg was a pioneer of research into female sexual reproduction and pleasure. A German gynaecologist, his work covered a multitude of aspects of the physiology of reproduction. He was the first to describe the physical connection between the stimulation of the growth of an ovarian follicle and that of the lining of the uterus, the endometrium. (However, it is not his name that forms the term Graafian follicle, but that of Reinier de Graaf, who also studied the developing follicle.) Grafenberg was also the first to describe the cyclical variation of the acidity of vaginal secretions, and published in 1918, a twenty-nine page paper on vaginal secretions. Some credit him with developing the first test for ovulation. To add to this, he was a leader in the production of birth control methods, developing the interuterine device (IUD), the Grafenberg ring in 1928, and later collaborating on the plastic cervical cap.

However, it wasn't until the last decade of his life that Grafenberg started a revolution in how the female urethra and its surrounding structures are viewed. In 1950, in the International Journal of Sexology, he published a ground-breaking article entitled 'The Role of the Urethra in Female Orgasm'. In this, he pointed out the pleasure women derive from stimulation of this organ: 'Analogous to the male urethra, the female urethra also seems to be surrounded by erectile tissues ... In the course of sexual stimulation, the female urethra begins to enlarge and can be felt easily. It swells out greatly at the end of orgasm.' Grafenberg also noted how the 'floor' of the urethra is the 'ceiling' of the ventral vaginal wall and how: 'An erotic zone could always be demonstrated on the anterior wall of the vagina along the course of the urethra. Even when there was a good response in the entire vagina, this particular area was more easily stimulated by the finger than the other areas of the vagina.'

Interestingly, Grafenberg found that the most sensitive part of the

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

anterior vaginal wall for the women in his study lay 3-4 cm inside the vagina - in the vicinity of the posterior urethra, just around where the urethra becomes the neck of the bladder. This is the area that over thirty years later was renamed the Grafenberg spot, or G spot, and is celebrated in the best-selling book The G Spot and Other Discoveries About Human Sexuality.

The vexing question of vaginal sensitivity

Grafenberg's work was viewed as highly controversial for two main reasons. First of all, he pointed out that the urethra was surrounded by erectile tissue, just as the male urethra is. Secondly, he highlighted how sensitive the interior of the vagina is. These comments on vaginal sensitivity went against the thinking of the time - which had tended to underline the supposed insensitivity of the vagina and the urethra. Indeed, many people today still claim that the interior of the vagina is insensitive. They are incorrect in their assumptions and, as we shall see, their claims are based on biased theories and flawed science. First of all, the idea of the vagina as insensitive has its roots in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century misogynistic and hypocritical notions of females being creatures devoid of all sexual sensitivities. Women, the great minds of these times opined, were not much bothered by sexual feelings. This view was promoted despite plenty of evidence to the contrary.

The idea of the unresponsive, insensitive vagina was also, unfortunately, given some credence by twentieth-century studies. Crazily, this research proclaimed that on the basis of the Q-tip test, or cotton wool bud test, the vagina was not very sensitive. It may be true that touching the tip of a cotton wool bud to the vagina's walls won't elicit much sensation, but that's hardly surprising or a robust touch test. Sex consists of far more than the touch of a Q-tip. What these studies did show, but failed for some reason to highlight, was the vagina's sensitivity to vibration and pressure.

In fact Grafenberg was correct about the sensitivity of the urethra and the interior of the vagina. Recent research has shown that female genitalia are profoundly innervated (by the pudendal, pelvic, hypogastric and vagus nerves) and capable of detecting vibration, touch and pressure changes, in particular deep pressure. Tactile stimulation of the extremely sensitive external genital skin produces one type of sensation, while deep-pressure proprioceptive receptors within the perineal and vaginal musculature produce exquisite sensations too - either as a result of contraction of muscles or their distension by a penis, fingers, vibrator or whatever. Visceral sensory receptors are also thought to convey arousal and orgasm sensations to the brain. This means the vagina is deliciously responsive

THE STORY OF V

to the low throb of slow strokes, the hard, persistent pressure of deep thrusts, or just simply squeezing the vaginal muscles.

Grafenberg was also correct about the particular sensitivity of the anterior vaginal wall. Recent studies into its microstructure and sensitivity have pointed to geographical differences in the innervation of the vaginal chamber. The deeper you go inside the vagina the more nerve fibres there are in the walls, with the anterior wall much more densely packed with vaginal nerves than the posterior one. There are also specific differences in the number and nature of nerve fibres found in the area of the anterior vaginal wall adjacent to the bladder neck. These include an extreme number of richly innervated vessels, plus the presence of yet-to-be-explained giant coiled corpuscle-like structures.

The revelation that the microstructure of a woman's vaginal walls suggests that they are far more sensitive than previously recognised is not surprising to me. I know the ability of my vagina to feel the merest flicker of movement when I am joyously and deeply aroused. One of the sweetest sensations of life is the delicate, pulsatile, tickling feeling of my man orgasming inside me. I don't know whether it's the ejaculatory spurt of semen or the contractile quiver of orgasm that I feel, but whichever it is, it's divine.

The female prostate

Some things, it seems, never change. For instance, the tissue surrounding the female urethra is still a subject of enormous controversy, more than fifty years after Grafenberg published his pioneering article. Today, though, the furore is focused on the fact that the tissue surrounding a woman's urethra is more than just erotically sensitive and erectile. Surprisingly, it is also secretory as a result of numerous glandular structures traversing its length and embedded in it. These glands and their connecting ducts empty their contents into the urethral passageway, and together the complex of secreting structures and its associated smooth musculature are known as the female prostate (see Figure 5.4). At the start of the twenty-first century, however, the above sentence is not accepted by all scientists. The tale of the female prostate is one that, in part, parallels that of its sister, the clitoris. It is a story of anatomical parts found and lost and found again. And like the clitoris, despite a wealth of evidence to the contrary, the idea that the female prostate may be a functioning part of a female's reproductive anatomy is doubted.

Pertinently, the presence of a female prostate has not always been denied. In fact, the existence of the female prostate was accepted for nearly two millennia - and only became a matter of dispute at the end of the nineteenth century. Greek anatomist Galen (130-200 ce) was one of the

OPENING PANDORA S BOX

spongiosum

^ v bladder female

vagina

clitoris

urethra

vaginal opening

Figure 5.4 The female prostate: the sprawling complex of glands and connecting ducts that is the female prostate can extend along the urethra.