Blow upon my garden, let its fragrance be wafted abroad Let my beloved come to his garden, and eat its choicest fruit.

The ecstasy of a woman's revealed perfume is a theme that seventeenth-century English poet Robert Herrick returned to again and again, in both 'Upon Julia Unlacing Herself, and 'Love Perfumes all Parts', in which he rhapsodises:

If I kiss Anthea's breast • There I smell the Phoenix nest: If I her lip, the most sincere Altar of incense, I smell there Hands, and thighs, and legs, are all Richly aromatical Goddess Isis can't transfer Musks and Ambers more from her: Nor can Juno sweeter be, When she lies with Jove, than she.

For various reasons, however, the pairing of the sense of smell with sexuality has not always been considered in a positive light. Early philosophers, noting the predilection of animals to go nose to genitalia prior to copulation, chose to rank smell as one of the lower senses. To them, it was an animal sense, incapable of raising humans to elevated heights of creativity, like the senses of sight and sound could and did in art and music. The philosophers of the Middle Ages regarded smell as a vulgar

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

sense, and one that in no way promoted human intellect. Astonishingly, both ancient and modern governments, perhaps recognising that you don't control a people unless you control their sexuality, have deemed perfumes dangerous and intoxicating enough to be banned or have their usage restricted. In 188 bce, Romans were forbidden to wear all but the most modest amount of perfumery in social ceremonies.

Sixteen hundred years later, the English parliament felt the need to pass an act in 1770 protecting men from 'perfumed women', for fear that scented 'witchcraft' might lure unsuspecting men into marriage. And by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the use of musk, amber and civet was discouraged, for fear of its detrimental and 'decaying effects'. One result of this anti-perfume attitude was that in 1855, Queen Victoria caused a furore during a royal visit to Paris. The problem? The British monarch was wearing perfume with a hint of musk - a scent that at that time was deemed more appropriate to a salon mondaine than the fashion-conscious French court.

Downplayed by philosophers, branded the animal sense and associate of sex, and bedevilled by its ephemeral nature, perhaps it's not surprising that the sense of smell remained a poor cousin of science for many centuries. Indeed, even today, smell remains the least researched and funded of humankind's five recognised senses. It wasn't until the end of the nineteenth century that hints that Hippocrates' hunch about a naso-genital alliance might be based in physical reality began to emerge. Charles Darwin, marvelling at the variety of facial and genital features in the animal kingdom, brought attention to them and to the extraordinarily similar naso/genital arrangement of the male mandrill. This Old World monkey's nose of vibrant vermilion red echoes its fire-engine-red penile shaft and anus, while its brilliant cobalt-blue paranasal ridges mirror its pale blue scrotum. The startling effect of this as above, so below colour scheme is topped off by the apparent mimicking of the mandrill's yellow/orange facial beard with pubic hair of a similar hue. Writing about the mandrill, Darwin said: 'No case interested and perplexed me so much as the brightly-coloured hinder ends and adjoining parts of certain monkeys ... It seems to me ... probable that the bright colours, whether on the face or hinder end, or, as in the mandrill, on both, serve as a sexual ornament and attraction.'

Other Old World monkeys display naso/genital links, and for some this association is underlined by changes in reproductive status mirroring those seen in the genitals and nose or face. Take female Japanese macaques. The faces of these female primates turn an even brighter pinky-red as their sexual perineal skin swells and blooms during their five-month-long mating period. Male Japanese macaques sport red sexual skin on their face as well as their scrotum and perineum, and out of the mating

THE STORY OF V

season, the loss of sexual skin colour is accompanied by their testicles retracting and ejaculation ceasing. In a similar vein, the flamboyant naso-genital blues and reds of the male mandrill become muted if the male is subordinate or solitary, or peripheral to a social group. And as his naso-genital colours fade, his testicles shrink too. Not surprisingly, such colour-challenged males do not enjoy as much mating and reproductive success as their more brilliantly hued brothers. It's also now appreciated that the growth of the extraordinarily long, fleshy and distinctly phallic nose of the male proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) is delayed if there is an absence of females in the social group. Peculiarly, some birds, as well as primates, exhibit naso-genital features connected with reproduction. This is the case for the male pelican, whose beak becomes swollen with a large bump during the mating season, despite the fact that this mars his field of vision and interferes with the catching offish.

The nose has a clitoris?

Following hot on the heels of Darwin s observations of comparable external naso-genital characteristics came the surprising realisation that the internal structures of the human nose and genitalia are actually strikingly similar. In 1884, American surgeon John N. Mackenzie pointed out that the respiratory and olfactory mucosae, which cover the conchae in the nose and, in the case of the olfactory mucosa, line the narrow olfactory slits, were composed of erectile tissue analogous to the corpora cavernosa tissue of the clitoris and penis. That is, the nose has a clitoris too. And, just like their genitalic counterparts, the blood vessels of these nasal tissues fill with blood, or vasodilate, in response to sexual excitement. So not only did the human nose resemble the genitalia, it also responded in a similar erectile manner too.

Nasal erections are, in fact, the reason behind the nasal stuffiness, congestion or rhinitis that is experienced by many individuals following orgasm, sexual stimulation or intercourse. And the idea that sex goes to the nose is, not surprisingly, recognised by those individuals who rely on their nose for their livelihood. Perfume testers, wine tasters and tea blenders are all aware of the condition known as 'honeymoon rhinitis' - a hypersensitised nose post-sexual activity. For me, the idea of nasal erections has resonance, having experienced personally such extreme nasal arousal post-orgasm. The feeling was of my nose being vibrant, literally quivering, suffused with sensation, and intensely aware of the sexual aromas surrounding me. One more sniff of the sexual landscape I was nestled in, and I felt I would surely dissolve in eternal orgasm. Sadly, I didn't, but the memory remains deliciously strong.

The enhanced blood flow to the nose, which is responsible for resulting

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

in nasal membrane engorgement, also accounts for a rise in temperature of the nasal mucosa. Experiments looking at nasal mucosa immediately before and immediately after sexual intercourse show a mean rise in temperature of 1.5°C. Cold temperatures, too, have an effect on the nose, constricting nasal structures as they do clitoral or penile erectile tissue. The rapid dilation of the erectile tissue of the nose is what is believed to be behind the sudden, and often paroxysmal, sneezing that can accompany sexual desire, genital erection, intercourse and orgasm. In his 1875 text Observations Rares de Medecine, Stalpart de Wiel mentions 'individuals in whom the act of coitus was often preceded by sneezing'.

John Mackenzie wrote in 1884 of a man of sanguine temperament, who every time he caressed his wife sneezed three or four times', while another researcher in 1913 noted the case of a man 'who frequently sneezed at the sight of a comely maiden'. Following one friend's confession of a similar naso-genital phenomenon brought on by sexually arousing thoughts alone, I now view his every sneeze with a wry, quizzical smile. Not just sneezing, but wheezing too, is tied in to sexual situations. The asthmatic breathing 'associated with stoppage of the nostrils' suffered by one Victorian woman was apparently alleviated when she did not engage in sex every night with her husband. Today sexual abuse is recognised as a stressor in cases of paroxysmal sneezing.

The emergence of naso-sexual medicine

The recognition at the end of the nineteenth century that there was a physiological relationship between the human nose and genitalia ushered in a new field of medicine - naso-sexual medicine. Over a period of approximately twenty-five years, a multitude of papers, books, lectures and dissertations were devoted to poring over the possible connections between the nasal passages and the sexual organs. During its heyday, naso-sexual medicine influenced many, including Sigmund Freud, to explore further the connections between the nose, olfaction, genitalia and sexuality. In 1912, at the tail end of the naso-sexual renaissance, E. Seifert proposed that there was a 'reflex neurosis' operating between an individual's genitalia and their nose, and that it was this reflex that was the key to understanding all aspects of human health and fulfilment.

Naso-sexual medicine also resulted in some curious remedies for gynaecological problems. At the end of the nineteenth century, Wilhelm Fliess, one of Sigmund Freud's closest collaborators, sought to pinpoint the precise areas of a woman's nose that were linked with her genitalia. His identification of these 'genital zones' or spots {Genitalstellen) on the olfactory mucosa of the nose - which had a tendency to bleed at various times associated with the menstrual cycle and pregnancy - then led to

THE STORY OF V

them being used as therapy sites for various gynaecological disorders. The treatments which proponents of nasal genital zones advocated included cauterisation, or the infinitely more pleasurable approach of applying cocaine nasally. During the heyday of naso-sexual medicine, if you were suffering from labour pains, or just plain dysmenorrhoea (painful periods), the doctor could, and did, prescribe a dab of cocaine up the nose for you. Fliess also suggested that several cases of apparently spontaneous abortion were, in fact, triggered accidentally, by intranasal surgical procedures.

Fliess, Mackenzie and other researchers in the field of naso-sexual science were also intrigued by the apparent effect of the menstrual cycle and of pregnancy on the female nose. Female nasal mucosa, it was noted, swelled and reddened, became more sensitive and congested, and subsequently bled, with a periodicity seemingly in concert with that of the 29.5-day human female menstrual cycle. Indeed, the occurrence of nosebleeds (epistaxis) during menstruation was referred to as vicarious menstruation - menstrual bleeding from an alternative orifice. It was also pointed out that, as many pregnancies progressed, an increasing proportion of women presented with either blocked noses or sporadic nasal bleeding.

However, it wasn't until the late 1930s that a scientific rationale for such rhythmic nasal events was realised. The nasal and genital skin of female rhesus monkeys provided the key. Hector Mortimer, a Canadian otolaryngologist, observed that the striking reddening and swelling of the sexual skin that these monkeys sport coincided exactly with the reddening of their nasal mucosa. For these primates, and some others (but by no means all), the sexual swellings of their ano-genital region reach peak tumescence immediately prior to ovulation, as the circulating blood levels of the hormone oestrogen come to a head too. Blood oestrogen levels, it was finally appreciated, had an effect on both a female's genitalia and her nose. The thinkers of old were correct in assuming a connection, or route, between the nose and the genitalia. Perhaps hormones are the mysterious hodos envisaged by Hippocrates.

It's now accepted that the human nose, and nasal membranes, are stimulated by circulating levels of hormones. Vasomotor rhinitis (inflammation of the nasal membranes) is a common occurrence in both pregnancy and puberty, both times in life when blood oestrogen levels soar. Increases in blood oestrogen levels during pregnancy have also been shown to correlate closely with nasal congestion. It's also interesting to note that around ovulation, many women report a heightened sense of awareness, coupled with (or probably as a result of) an increased sensitivity to odours - again, a result of the effects of circulating hormones on their nasal mucosa. This lower female threshold to aromas around the

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

time of ovulation has also been documented in the laboratory.

The hormonal connection between the nose and the genitals is also underlined by a number of medical conditions. Chronic under-devel-opment of the nasal membranes (atrophic rhinitis) is often linked with irregular or non-existent periods (amenorrhea), while Kallman's syndrome is associated with no sense of smell (anosmia) and undeveloped gonads: in women the ovaries contain only immature egg follicles, while men present small testes, do not produce sperm and a prostate cannot be felt. Losing one's sense of smell also has a negative effect on sexuality, with over a quarter of anosmia sufferers becoming sexually dysfunctional. The sense of smell, it seems, is integral to both human sexual development and adult sexuality.

Would like to meet ...

Human anatomy and physiology highlight how the nose and the genitalia are related, with hormones the messenger molecules shuttling information to and fro via the blood. But why this intimate connection? Why should the nose and the sense of smell be so tied up with human sexual anatomy? The answer lies many millions of years back in time. At its most fundamental level, the sense of smell is the ability of an organism to respond to chemical cues in its environment. At heart, therefore, smell is chemosensory, a chemical sense. It requires the presence of molecules, particulate matter, in the air or water, to effect sensation.

Smell is also an original sense. Communicating via chemicals is as old as life itself, and is an attribute of all organisms on earth, from the smallest to the largest. Even the simplest and most ancient unicellular creatures, which have neither a nervous system nor specialised sensory apparatus, possess the ability (courtesy of chemo-receptors) to respond to chemical cues (chemo-signals) in their environment. Using chemical communication - smell - they find food, or avoid danger, be it toxic substances or predators. And when sexual, rather than asexual, reproduction first arose (an event believed to have begun about a billion years ago), the chemical sense of smell was the only system in place to enable procreation to occur. This, then, is the core reason why smell has a very powerful and central role to play in sexual reproduction. Other senses may since have been co-opted to the job, but smell remains a prime mover.

Sexual reproduction, it is surmised, has a watery origin. Before humankind's ancestors were multiplying on land, they were doing it at sea. But sex at sea, as highlighted earlier, is a risky business for those ocean-dwellers that do not possess internal genitalia. For both sexes, spawning, using the surrogate womb of the vast sea, is fraught with added dangers. Release your gametes at the wrong time or in the wrong place and your

THE STORY OF V

shot at procreating stands to be scuppered as" your eggs or sperm are washed away before encountering anyone else. Timing - being able to coordinate sexual reproduction - is all. And the key to acquiring such rhythm is being able to sense and respond to the presence of others around you. Are they members of the same species, are they of the opposite sex, and are they sexually ripe? Answer yes to all three, and in the absence of immediate danger, and the result could well be the mutual orgasmic rhythmic contractile expulsion of gametes into the surrounding waters. Curiously, many chemicals that cause such explosive and ejacu-latory reactions in ancient creatures, such as the sea squirt, are those that humans utilise today, perhaps with a slight spin, or different emphasis, but with the same end result in mind. Human gonadotrophin (ovary- or testis-stimulating) hormones also effect the release of a sea squirt's gametes. Some things just don't change. If it works well once, Mother Nature will use it again.

Over a hundred years ago, German biologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel envisaged olfaction as a primordial attractive force in the cop-ulatory union of female and male gametes. His theory of erotic chemo-tropism viewed gonadal cells as possessing a primitive consciousness (Seelenthatigkeit), and seeking each other out via a type of primitive smelling. To Haeckel the attraction one organism has for another of the opposite sex was a conscious reaction to the prompting of its gonads. Intriguingly, in light of Haeckel's surmisings, it's now realised that once released, even gametes themselves work to meet their other half. Both the female and male gametes of the aquatic fungus Allomyces macrogynus release chemicals which enable their mutual orientation towards each other. The female gametes secrete a compound dubbed sirenin, which acts as a sperm attractant, causing an influx of calcium ions into the cytoplasm of any nearby sperm, and a subsequent change in their swimming pattern and a shift in movement toward the source of the chemical -the female gamete. The male gametes too produce an attractant, named parisin, which the eggs sniff out and then swim towards. Such simple chemo-sensory systems are believed to be the ancestors of life's more specialised communication systems of hormones (messenger molecules which are released internally within a given organism) and pheromones (communication chemicals released by an organism into their immediate environment).

It's important to remember, though, that mammals are far from being simple unicellular organisms. Rather, we are highly evolved creatures, comprised of multiple specialised organs, glands and complex communication systems. In mammals, the nose is the primary chemo-sensory organ, receiving olfactory information and relaying it directly and rapidly to the brain. The conventional view of human chemo-sensory sensitivity

THE PERFUMED GARDEN Table 6.1 Major Scent Gland Regions of the Body

Major anatomical sites Gland type

Sebaceous Apocrine

Scalp Face

Eyelids * *

Ear canal * *

Vestibulum nasi (nasal vestibule) * *

Upper lip *

Lining of mouth *

Axillae (armpits) *

Nipples and areolae *

Midline of chest *

Umbilical region of abdomen *

Mons pubis *

Labia major a * *

Labia minora *

Prepuce/glans penis *

Scrotum *

Circumanal/anogenital/perineum *

Human sebaceous glands produce sebum - a thick, oily, unpigmented secretion. Their function is thought to be linked to sexual reproduction as the glands only begin to secrete once puberty is reached. Genital skin has the highest density - with up to 900 sebaceous glands packed into every square centimetre of skin. Human apocrine glands produce a viscid, oily substance which has a surprising range of colours. It can be milky pale grey, clear white, reddish, yellowish or even black. Like sebaceous glands, apocrine glands only start to function at puberty, suggesting that they too have a reproductive role. Women have far more apocrine glands than men. Adapted from Stoddart, D. Michael, The Scented Ape: the Biology and Culture of Human Odour, London: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

is that in comparison to the supersniffing abilities of other mammals, such as bloodhounds, humans just don't make the grade. This, though, is a misrepresentation. Okay, humans are not up to the smell-detecting standards of bloodhounds, but our olfactory sensitivity is not something to be sniffed at. Humans can recognise at least 100,000 different odours. Humans are also incredibly smelly creatures as a result of numerous secreting scent glands scattered across our skin surface (see Table 6.1). Indeed, among primates, humans seem to be the species most richly endowed with scent-producing glands, smell structures which start firing on all cylinders at puberty- in concert with our reproductive organs. And smell is a sense we can't avoid. We can close our eyes, cover our ears, but we can't stop smelling. Each inhalation brings an enforced inspiration of

THE STORY OF V

aromas. The scent of fear, the smell of food, the odour of arousal; humans, like other mammals, recognise these fragrances and learn to follow their noses. Considering this, it's not too far-fetched to imagine that chemo-sensation could very well be an important factor in communicating human sexual and social information, just as it is in simple organisms.

Girls are made of sugar and spice?

I have two favourite smells. The savoury aroma of my mum's slow-cooked meat and potato pie; and the heady, rich scent of my fertile cunt. Familial love and sexual love, described by mere chemicals. My much-loved vaginal perfume is the deepest, truest smell of me. It's the scent of my fertility, my sexual ripeness and pleasure. It's mercurial too, starting on day four or so of my menstrual cycle. From then until I've ovulated, I am intensely aware of this rich, sweet, deep, creamy and aromatic vaginal incense. Post-ovulation it's somehow fruitier. Although rarely openly discussed, the sexually pleasing and powerful scent that a woman's vagina and its secretions exudes is no secret. This intimate and erotic smell and taste is a sensual joy that different cultures have lauded and lusted after for centuries.

History relates how courtesans in medieval Europe used their sexual secretions as perfume, anointing themselves behind their ears and around their necks, in order to attract customers. It's also said that women in southern Spain would rub a small dab of their vaginal juices behind their ears and into their temples. Mixed in with the delicate essence of themselves were other fragrances, such as jasmine, neroli, myrrh, ylang ylang or frangipani. This particular tradition is understood to have been the secret of Taoist mistresses in ancient China before it was passed on to the Moors and from them to the Spanish. Meanwhile Napoleon is famously meant to have requested that Josephine 'not wash' before he arrived home, while Henry III reportedly remained in love with Mary of Cleves all his life after smelling the scent of her undergarments.

The classical Indian sexological text the Ananga Ranga is one surviving document which depicts in glorious detail the sensorial appeal of the vagina. Women, it says, fall into one of four classes, and it then goes on to praise women in terms of their genital scent, taste and style. First, the vagina of the padmini (Sanskrit for lotus-woman) is said to resemble the opening lotus bud, and enjoy feeling the rays of the sun and the touch of strong hands. Her sexual secretions (Kama-salila) are perfumed like the lily that has newly burst. The chitrini (the art-woman) can be recognised by her soft, raised and round mons veneris and sweet honey-smelling vagina. Delightfully, her genital fluids are said to taste of honey too. They are also exceptionally hot, and so abundant that they make copious sounds. Then there's the vagina of the shakhini (the fairy- or conch-

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

woman), which is, apparently, always moist and loves being kissed or licked. Her genital juice tastes piquant or salty. Finally, the fourth order of woman is the hastini (elephant-woman), who takes great pleasure from much clitoral stimulation. Her sexual secretions have the savour of 'musth' - the musky juice which flows from an elephant's temples signalling their sexual excitement.

The strength of the association between female genitalia and their smell is underlined, dramatically, by language. 'Pillow of Musk' and 'Open Peony Blossom' are two Chinese ways of saying vagina, while in eighteenth-century England, honeypot, rose or moss rose were all used to describe the sexual heart of a woman. Honey's vaginal reputation is tenacious. It is not only the Ananga Ranga that talks of sweet honey-smelling vaginas; others say all women's vaginal juices taste of honey during certain days of the menstrual cycle. It's surely no coincidence that honey is a core component of many marriage ceremonies, such as the Hindu custom of daubing the bride-to-be's vagina with honey at the marriage feast, or that newly-weds enjoy a honeymoon. Honey also enjoys a reputation as an aphrodisiac, and, of course, we call our loved ones honey.

The myrtle is another deeply perfumed plant that history records as redolent of female genitalia. The 'fruit of the myrtle' is a term that over the years has been used to describe both the clitoris and the labia minora, while a woman's outer lips (labia majora) were, according to the first-century Greek physician Rufus of Ephesus, the lips of the myrtle. Myrtle, with its pink or white flowers and aromatic blue-black berries, is also the sacred plant of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. Legend recalls that when Aphrodite emerged from the waves riding on a sea-shell, only to have her nakedness leered at by lewd satyrs, she chose to cover her genitalia with branches of the fragrant myrtle bush, which grows best near the seashore. It is said that the Greeks identified this plant more than any other with all things that smelt beautiful, and, indeed, the Greek name for the myrtle (murto) derives from the same root as that for perfume. And not surprisingly, considering its link to Aphrodite, the myrtle is also considered to be a powerful aphrodisiac. For example, Dioscorides, in his pharmacology compendium De Materia Medica, describes myrtle oil as refreshing, aphrodisiac and antiseptic when taken in tea.

'Streaming with the essence of the lily'

How would you describe the heady scent of female genitalia? Is it the scent of the lily or lotus, of sweet aromatic honey? Or is it the 'musks and ambers' that poet Robert Herrick says his lover smells of? One of the most beautiful descriptions of a woman's secret scent comes, I feel, from Pierre

THE STORY OF V

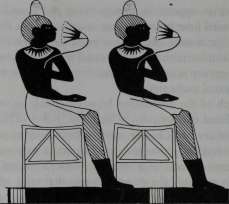

Figure 6.2 From a painting found at the tomb of Nakht, in Thebes, depicting a feast (eighteenth dynasty). The guests wear cones of myrrh attached to their wigs and sniff the aphrodisiacal scent of blue lotuses.

Louys, who writes of how he feels he is 'streaming with the essence of the lily' as he lies with his cheek on the belly of a young woman. This phrase evokes such potency and pleasure, it's stunning. Nor was Louys alone in dreaming of the vagina as a lily. Lilies or lotuses (the lotus flower is a type of water-lily) are a common symbol of the vagina or yoni, in particular in eastern cultures. For example, the Sanskrit word for lotus is padma, which is also a word for the yoni. Chinese sexological texts refer to the vagina as a Golden Lotus, while the Latin name for the lotus is nymphaea, a term applied to a woman's inner labia too.

Some curious and unexpected connections between the lotus and female genitalia are suggested elsewhere. In Greek mythology, the lotus is represented as a fruit that induces a dreamy languor and forgetfulness in those that eat it. Lotus-eaters lie around languidly all day, partaking of the legendary fruit. Precisely what this fruit is is never spelt out, although if it is code for the vagina, then it gives a whole new meaning to the term lotus-eating. Peculiarly, though, lotus-sniffing was one of the pastimes of ancient Egypt. Numerous illustrations show both women and men plunging their noses into the scented heart of the blue lily or lotus (see Figure 6.2). The significance of this act, which appears to be part of ancient Egyptian pleasure rituals, had puzzled historians for years. However, recently scientists came up with an intriguing suggestion.

Astonishingly, sniffing blue lilies acted as an aphrodisiac. Why? Well, this particular lotus has a pharmacological quality akin to that of the prescription medication Viagra. Both contain a chemical, the former natural and the latter not, which results in increased blood flow to the

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

genitals. It seems that the scent of the lotus - whether describing the actual flower or female genitalia - really is a potent aphrodisiac. And lotus and vagina actually are connected via smell. This property of the lotus is also perhaps why the lotus is a sacred flower for Indian, Persian, Egyptian and Japanese cultures.

If I was forced to pick a third favourite smell, I would have to plump for vanilla. In terms of fragrance, vanilla belongs to what is called the ambrosia or musk-like category of scents (the seven classes of odours are detailed below). And not surprisingly, perhaps, the perfumes typically used to describe the vagina fall within this particular category. In fact, it could be said that ambrosial scents are, in essence, the intimate scents of a woman. Musk, lily, amber and vanilla, all creamy, luxurious and sensual fragrances. More specifically, ambrosial scents are said to have their roots in amber, the resinous product of the intestinal tract of the sperm whale. Fragrant and attractive, the Greeks referred to amber as elektron - a substance that when rubbed releases charged particles. For the Greeks, ambrosial scents were regarded as both the elixir of life and nourishment for the gods.

The smell of vanilla is certainly an ambrosial aroma. It's also a smell that is commonly used to describe the scent of female genitalia, and this aroma association is again underpinned by language. A vanilla is actually a tropical climbing orchid with fragrant greenish-yellow flowers and long fleshy pods containing seeds or beans. It is these vanilla beans and pods that are used as flavouring for foods. However, the Latin American orchid was given the name vainilla by Spanish settlers because its pods - which have an elongated outline with a slit at the top - were said to be reminiscent of female genitalia (no mention is made of whether the smell triggered any memories too). Vainilla is the Spanish diminutive for vagina or sheath. Hence, vanilla literally means 'little vagina'.

The taxonomic system that places vaginal fragrances together was devised by the eighteenth-century Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. Linnaeus chose to group odours into seven classes in terms of their hedonic, that is, their pleasurable, qualities. These classes are Fragrantes (fragrant, such as saffron and wild lime); Hircinos (goaty, the smells of cheese, meat and urine); Ambrosiacos (ambrosial or musk-like, as we've seen); Tetros (foul; this includes the walnut, also known as Jupiter's Nut or glans of Jove); Nauseosos (nauseating, like the foul-smelling resinous gum asafoetida); Aromaticos (aromatic, the spicy notes such as citron, anise, cinnamon and clove) and Alliaceous (like garlic, which is a type of

lily).

Linnaeus wasn't shy about talking about smell. He held that the fragrance of the may flower - the blossom of the may tree or hawthorn -recalled that of female genitalia. This is an association that has survived

THE STORY OF V

since medieval times, when may blossom was picked on a May morning and worn by revellers dancing around the maypole on a day dedicated to sexual pleasure. Linnaeus also saw several varieties of rose as reminiscent of female genitalia, and indeed, pink and red roses were common vaginal symbols in the west. Strangely and sadly, though, the plant that Linnaeus chose to bear a directly vaginal name, Chenopodium vulvaria (also known as stinking goosefoot), is reported to smell fish-like. Peculiarly piscine is not the scent of a healthy, clean vagina; rather this is the signature note of a bacterial vaginal imbalance, just as the reek of rank cheese is that of a bacterial penile imbalance.

The deeply conservative Linnaeus is also famous for describing plants in terms of their vaginal and penile attributes, their pistils and stamens respectively, as well as referring to their reproduction systems as their marital tendencies. In this vein, he divided the plant world into different classes according to the type of marriage each plant contracted - be it monandrian (one husband, penis or stamen), diandrian (two husbands, penises or stamens) or more, or whether the marriage was public or clandestine. His wife he referred to as 'my monandrian lily', lily having been spun to imply virginal in the west in contrast to its role as a vaginal symbol in the east.

Spice boxes

So why do women smell the way they do? There are two answers to this question. The first centres on the literal reasons for this - the composition of a woman's genital juices and where these secretions come from. The second concerns the effect that a woman's scent has on other individuals, that is, the vital message it conveys. First off, what's in the vaginal mix? Importantly, the source of a woman's sexual aroma is not singular. Vaginal secretions, as earlier shown, are a complex cocktail, exuding throughout female genitalia. Cervix, uterus, Fallopian tubes, vaginal walls, prostate, all these and more add to a female's bountiful fluids. Deliciously, the French refer to this confection of aromas as a woman's cassolette - her cooking pot of fragrances.

Female genitalia also incorporate specialised mucus-secreting glandular structures. These include Bartholin's glands (also called major vestibular glands), which are set deep in the lower half of the labia majora, close to the vestibular bulbs and bulbocavernosal muscle. These glands secrete fluid through an excretory duct, 1.5 to 2 cm long, which opens either side of the lower edge of the vaginal opening or vestibule area (at five and seven o'clock). Dotted around the vagina's vestibule are minor vestibular glands of varying numbers. The average is between two and ten, although some women have more than a hundred, and some have

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

none at all. These minor glands also exude fluid. Apocrine glands, scattered around the genitals, also add to the aroma medley.

A woman's inner lips, her labia minora, provide a rich addition to her perfume. Despite not having any hair follicles, the inner labia contain large numbers of sebaceous glands (the small skin glands that emit lubricative and protective sebum on to hair follicles and surrounding skin). These labial sebaceous glands secrete a white oily substance, similar to that produced by a man's preputial skin. This genital secretion fascinated me as a child, although I didn't know, and didn't ask, what it was. For some reason, dark-haired women possess more of these inner labial glandular structures than their blonde sisters do. The labia majora (outer lips) are also rich in sebaceous glands, adding another note to a woman's sexual scent. And if allowed to flourish in all its springy lush splendour, a woman's pubic hair - the triangular crowning glory of her genitalia - then sets off a woman's vaginal perfume perfectly, and piquantly. As nineteenth-century French poet Charles Baudelaire put it:

Languorous, black, luxuriant locks Live pomander, incense burner Wafts her wild, musky fragrance

A woman's Bartholin's glands are reputed to be a key source of her signature sexual scent, although there is, as yet, scant evidence in support of this. What is known about this genital fluid is that it is clear, mucoid, alkaline, under ovarian hormonal control, and increases during sexual arousal. These mucus-secreting glands are present in other female mammals. In the platypus, the ducts open at the base of the monotreme's clitoris. In female opossums the secretions flow into the canal of the urogenital sinus, while in female spotted hyaenas, with their queenly elongated clitoris, complete with urethra running through it, the extremely well-developed Bartholin's glands open into the urethra close to the tip of the clitoris. The equivalent male mammalian structures are called Cowper's, or bulbourethral, glands.

Many female mammals also produce clitoral gland secretions. In the rat, the main excretory duct of the clitoral gland courses along the surface of the clitoris, emptying on the side of the urethral opening, thus communicating with both the urethra and the vagina. Studies show that the odour of these clitoral/urethral secretions is highly attractive to male rats. The clitoral glands are, in fact, homologous to the male's penile preputial glands, which appear as paired structures on either side of the penis. Many mammals' preputial glands are known to be of prime importance in producing secretory and olfactory products. For example, the preputial

THE STORY OF V

pouch of male Himalayan deers is the source oFthe red, jelly-like secretion that is musk.

In comparison, though, to what is known about male accessory glands, very little is known about the female's. This paltry state of affairs is highlighted both by the scientific community's ignorance regarding the existence and function of the female prostate, and by the recent revelation that women have more genital glands than previously thought. In 1991, scientists discovered a completely new type of female genital gland, and intriguingly, it has so far defied all attempts at classification. These ano-genital or vulval glands extend deep into the dermis (the inner layer of the skin), twice as deeply as eccrine or apocrine glands, and cannot be categorised as eccrine, apocrine or mammary glands. Ultrastructurally they are unique, as is their vulval secretion product. Although tentatively described as sweat glands, their function remains unknown. Their discoverers call them remarkable, suggesting they may have some sexual function, possibly of an olfactory nature.

Weirdly, their morphology is similar to that of mammary glands, and, indeed, occasionally the glands reach such a complexity that they appear lobe-like. Even more strangely, the existence of this type of vulval gland is suggested to be at the root of a strange and rare medical condition whereby women develop lactating mammary glands in their vulval skin. This peculiar and puzzling genital condition may well account for cases in the past where women were labelled as witches, and killed, as a result of marks akin to nipples on their external genitalia. It's certainly the case that most of the so-called witch marks or devil's teats that were found on middle-aged or elderly women during medieval Europe's witch hunts were noted as being on their vulval skin. 'Mary had teats in her secret parts and they are not like haemorrhoids,' reads one witch-finder's report.

Flagging up fertility

Female genitalia undoubtedly smell memorable and have the requisite odour-producing plumbing in place to give off sexual scent signals, but do they actually do this? After all, merely possessing the hardware is no proof of use. Moreover, is there an effect on other individuals as a result of them smelling parfum femalia 7 . An increasing body of evidence suggests that the intimate scent of a female does stimulate such a response, sometimes with startlingly dramatic results. It has long been noted that in the mammal kingdom going nose to genitalia is a typical prelude to sexual activity. In his notebooks, not intended for publication, Charles Darwin wrote: 'We need not feel so much surprise at male animals smelling vaginae of females - when it is recollected that smell of one's own pud. [pudendum] not disagree.'

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

Tellingly, the majority of male primates pay particular attention to the smell and taste of female genitalia - frequently sniffing, licking and touching the vagina for a number of days each month. For some primates this investigatory behaviour only occurs during oestrus, while others, in particular spider monkeys, sniff female genitalia repeatedly at all phases of the menstrual cycle. In some primate species mutual genital licking or nuzzling is common too. A more detailed vaginal inspection is part of the sexual ritual of mangabeys, macaques, baboons, gorillas, orang-utans and chimpanzees. This involves one or more fingers being used to poke inside the vagina too. The probing digits are then sniffed or licked. Many other male mammals, including red deer, moose and caribou, pay particular attention to licking the female's vulva, as do some species of insect. Oral sex is also a central feature of the sex life of a species of bat, the Gray-Headed Flying Fox, with the male deeply tonguing the female's genitalia for long periods of time. Unfortunately, whether or not it is scented stimuli and information that the male bat is seeking, or something else altogether, is still unclear.

However, some studies do point to female genital secretions signalling the status of a female's sexual ripeness. Research with male rhesus monkeys suggests that the sexual status of the female (is she ovulating or not?) is recognisable from her vaginal aroma, and that the time of ovulation is associated with the maximum frequency of male ejaculation. Mice, as well as monkeys, produce vaginal secretions that play an important role in male mating behaviour. Mice studies, though, reveal an extra twist. Female genital oestrous odour only stimulates male mice to approach and mate if they are sexually experienced. Virgin, sexually naive male mice appear not to hear the olfactory call. Clitoral gland secretions are the calling card of female rats too. These rodent scent glands produce an array of attractant aromas - one of which (6,ll-dihydrodibenz-b,e-oxepin-11-one) preferentially attracts males. Amazingly, the scent of a fecund female rat is enough to give a male rat an erection - no physical stimulus is necessary.

The allure of broccoli

The Syrian golden hamster possesses one of the most researched vaginal secretions, and one that is both alluring and arousing to the opposite sex. The night before oestrus, the female hamster marks the perimeter of her territory with her copious, watery vaginal secretions, effectively laying down a genital trail that lures the male to her underground lair. The major attractant molecule in her genital fluid is believed to be dimethyl disulfide, a chemical that smells a little like broccoli and is extremely common in nature - it acts as a nipple attachment molecule in pup rats,

THE STORY OF V

as well as being a principle malodorant in human tooth disease. But there's more to come in hamster vaginal mucus. The later stages of golden hamster courtship and copulation are induced by a protein, dubbed aphrodisin, which the male laps up as he licks the female's genitals prior to intercourse. Interestingly, physical contact with aphrodisin is essential in eliciting the male's mounting and pelvic thrusting response.

Unlike golden hamsters, precisely what it is about primate vaginal secretions that signals a woman's reproductive status is still uncertain. Research has highlighted how the chemical composition of vaginal mucus fluctuates throughout the menstrual cycle. Of particular interest are levels of fatty acids, which are produced by the action of essential vaginal bacteria. In rhesus monkeys, levels of these volatile short-chain fatty acids nearly double in concentration prior to ovulation. The same range of molecules plus some other sister compounds are also present cyclically in human vaginal secretions, and have been found to peak in concentration in the period prior to ovulation.

On average a woman's cocktail of genital mucus contains the following concentrations of fatty acids or copulins per ml of secretion:

10.0/ig of acetic 7.0/ig of propionic 0.5 //g of iso-butyric 6.5 jug n-butyric 2.0//g of iso-valeric 0.5 /zg iso-caproic

However, levels vary markedly from woman to woman. One study found that while 63.5 per cent of women had all these fatty acids present in their vaginal secretions, 2.5 per cent had no detectable fatty acids at all, and 34 per cent possessed only acetic acid. Importantly, research also revealed that women who take oral hormonal contraceptives have far lower levels of vaginal fatty acids and do not show the expected increase in concentration mid-cycle. This is not surprising, as levels of vaginal fatty acids are under the influence of internally produced (endogenous) oestrogen. Taking the pill, with its synthetic oestrogenic component, will disturb a woman's natural hormonal equilibrium, and hence a woman on the pill will smell slightly different.

Research investigating how the smell of a woman's vagina is perceived by men has thrown up some contrary results. Of particular interest is the vagina's aroma around ovulation. One study synthesised primate vaginal fatty acids, creating copulin mixtures that mimicked vaginal secretions at various stages of the menstrual cycle. Most men exposed to them said they found them to be unpleasant, perhaps a surprising result, although

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

it has to be recognised that in matters of smell and sex, context, including chemical context, is all. Yet, although the male sniffers appeared to turn up their noses at the copulin concoctions, when they were asked to sniff the synthetic copulins while looking at photographs of women, images they previously rated as ordinary were suddenly reported as being attractive.

It seems the effect of inhaling copulins made their sexual judgement go to pot. What's more, the copulin smells mimicking ovulation made their testosterone levels rocket, suggesting that the chemo-signals a woman gives off may play a role in regulating testicular function. This research tallies with other studies showing that even though most men say they are not aware when a woman is ovulating, their bodies know, as they respond physiologically with increased testosterone levels.

Other, more recent work reveals that men are able to distinguish when their partners are ovulating from smell alone. What is also significant is that these ovulation or fertility aromas were rated more attractive than others. Importantly, there were two major differences in this study. First of all, the odours analysed were naturally produced, and secondly, the women secreting them were involved in long-term relationships with the men smelling them. In this scenario, naturally produced odours emitted around ovulation were rated by this group of men as more pleasant than at any other time of the menstrual cycle. They were also perceived as tending to stimulate and linger for longer, and at the same time produced a desire for more chemo-sensory stimulation. I would suggest that this points to men being able to distinguish, albeit unconsciously, when a woman is ovulating, and to this ovulation aroma being attractive.

A final test of the pulling power of a woman's fertile vaginal perfume is, of course, whether it increases sexual activity or not. With rhesus monkeys, the answer is emphatically yes. Application of a copulin mixture to females unleashed hugely increased levels of male sexual behaviour. However, the results for humans were more equivocal. Women who rubbed synthetic copulin confections into their skin did not report any significant changes in sexual activity with their partner. In fairness to humans, though, this result probably says far more about the complex emotional and sexual lives we lead than our capacity to be influenced by a purportedly aphrodisiacal smear. It may also say something about synthetic copulins.

The odour avenue

Before looking at the reasons why the smell of her genitalia should flag up a female's fertility, what about other genital aromas? For it's not just vaginal secretions that are important in signalling a mammalian female's

THE STORY OF V

reproductive status - that is, gametes ready "to be released or not, or pregnancy underway. Mammals are rich repositories of odours, with humans no exception, and a whole host of other bodily fluids - including urine, saliva, sweat, tears and more - have been found to exert erotogenic effects in different species. Urine, the original odour avenue, is of immense importance. Composed of a welter of compounds churned out by the kidneys, urine is also perfumed as it makes its way out of the body by all it passes by - in particular accessory glands such as the prostate.

The power of urine to convey information about the status of an individual is astounding. Health, stress levels, reproductive and social status, metabolic idiosyncracies - all can be read from a simple sample of urine. Human urine tends to be dismissed as an excretory waste product -something to be washed away as quickly as possible - rather than an important genital fluid. But female urine is potent, as anyone who has sat waiting for a pregnancy test result can confirm. It stands shoulder-to-shoulder with vaginal secretions in conveying a woman's fertile status, a fact that simple ovulatory kits exploit (other ovulation detection devices resemble wrist-watches and measure the changing acidity of sweat, as determined by a woman's fluctuating hormone levels).

Urine's fluctuating and sometimes intoxicating scent has a sexual potency too - a fact that has not been overlooked by all. The erotic portent of female urine is part of the vaginal qualities prized in Marquesan society. To this end, certain edible fruit, anthropologists report, are not given to girls because they disrupt the pleasant aroma. In India, the smell of a young bride's urine was used in a wedding ritual designed to capture her bridegroom's heart. This practice, known only to women, involved wicks being made out of rags wet with the bride's urine, which the unsuspecting bridegroom was then asked to smell. Magic traditions also suggest that one way for a woman to keep her man in thrall to her is to urinate in his coffee. I haven't tried this one yet, but it has been recommended to me.

Considering the rich potential of urine to signal reproductive status, do females use their urine in this way? The habit of male mammals to use urine or accessory gland fluids to mark their environment is well known, but what about females? Disappointingly, relatively little has been written about how female mammals void urine and their own brand of marking fluids in order to communicate information about themselves, although this is common too. Yet, as more research is undertaken looking at this aspect of female mammalian sexual behaviour, the importance of females using the aromas of their body fluids to advertise their sexual and social status is becoming increasingly evident. The list of female spray-and-displayers includes tigers, monkeys, pigs, pandas, horses and more.

Female pigs (Sus scrofa) urinate frequently when in oestrous in order

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

to let surrounding males get the message that they are now fertile. When a male picks up a sow's fecundity flag, he follows its scent to her, but first finds her urine, sniffs or licks it and then urinates too - on top of her marking. Thus begins pig copulation. Female horses and deer also urinate as a sexual gesture. The effect of their oestrous urine on males is striking -the male's head is thrown back, his upper lip curls, and the pressure resulting from this contraction of the lip-raising muscles results in increased exposure to the female's urine. This facial expression is known as the flehmen, the lip-curling or flared face, and is seen in other mammals too (the word flehmen derives from a German word for coaxing or cajoling).

In the case of horses, the oestrous smell excites stallions to approach the mare, and engage in licking and tactile stimulation of her. The vivifying power of female urine on males is demonstrated more precisely by the effect of female house mouse urine, which stimulates a rapid rise in circulating levels of luteinising hormone (LH) in males. Such effects are seen in primates too. Male lemurs experiencing the effects of seasonality (fewer hours of sunlight during the day) have lower testosterone levels, and are less socially active and less likely to mate. Smelling female lemur urine, though, is enough to raise their testosterone levels and reanimate them socially and sexually.

Female Asian elephants are one of the mammals whose use of urinary signals has been studied in some detail. The oestrous cycle of female elephants is long - between sixteen and eighteen weeks - yet their fertile period is short, believed to be several days, though it may be only a few hours. Flagging up female elephant fertility effectively is therefore critical in determining successful sexual reproduction. Urine solves the timing issue. When female Asian elephants are feeling fecund they signal this to the males by releasing a particular chemical - identified as (Z)-7-dode-cenyl acetate - in their urine. This functions as both a sexual attractant and a reproductive-timing signal.

Where this chemical message originates from, though, is uncertain. The urogenital tract of female elephants, which is extremely long and winding (measuring between 120 and 358 cm from vulva to ovary), is packed with extensive mucus-producing glands, which may be the molecule's source. Alternatively, the copious amounts of urine which flush from the kidneys down the elephant's urethra-cum-vagina may be the culprit. It's also suggested that vaginal and/or anogenital secretions help to advertise the female elephant's fecundity. Around ovulation, females smear the hairy end of their tail with vaginal secretions and then fling the tail in the air - raising it like a flag and spreading their sexual signals further. I like this inventive approach to shouting, 'Come here, I'm ready.'

THE STORY OF V

An adapted clitoris?

Some women occasionally envy men for their possession of a tool that enables them to piss while standing up. Women's genitalia, unfortunately, aren't quite so effective at this task. However, one primate female has an extra trick up her sleeve. This primate is the female spider monkey, who, if you remember, has the longest clitoris of any primate. Some say this pendulous erectile organ resembles a penis. However, unlike a penis, it has a broad, shallow groove along its perineal surface along which urine flows (after it is voided at the base of the clitoris). The epithelial lining of this groove is also unique, appearing smooth and more like a mucous membrane. Females like to travel widely through the high canopy of remnant forests in Brazil, and as they do so they mark tree branches with their urine - their calling card - and call out to prospective mates. This tactic of distributing urine and finding potential suitors seems to work very well for the female spider monkey. They are incredibly sexually active primates, choosing a variety of partners, and it's suggested that their ability to distribute their urine via their clitoris plays a part in this.

The idea that female genitals are designed, in part, to distribute urine is not unusual and is used to explain some penile designs. The male goat, for instance, everts its prepuce to form a pendulous tube fringed with hairs - all the better for spraying urine far and wide. Whether other female primates utilise their external genitalia in this way is unknown. In the New World primate family, there are four groups where clitoral enlargement occurs - Ateles, Brachyteles, Lagothrix and Cebus. The clitoris of Cebus capucinus measures 18 mm, while that of Ateles belzebuth extends away from the body for 47 mm (no internal measurements are known). The reasons behind these alterations in genital design remain to be determined - it may be with extended urine dispersal, or possibly extra sexual pleasure in mind, or both.

The inner labia of women also pose something of a design puzzle. One suggestion is that their secretions contribute to a woman's olfactory bouquet, in particular when sexual arousal results in their surface area swelling markedly. However, the fluted nature of a woman's inner labia also sings to me of a design with fluids in mind - be it for urine, prostatic or other vaginal secretions. I don't believe I am the first to have thought this. For a long period of time, from at least the first century to the sixteenth, these vaginal inner lips were, as we've seen, commonly known as nymphae (singular, nympha), a word meaning 'water goddesses' in Greek.

And finally, a brief word on a musky genital fluid that is a bit of a mystery. Basmati rice, the night-blooming bassia flower, mung beans and female tigers may not appear at first glance to have much in common,

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

but they do. Connecting these four disparate items is 2-acetyl- 1-pyrroline (2AP), a seemingly innocuous molecule. The smell, though, of 2AP, is exquisite and not easily forgotten. It is the heady and particular aroma of basmati, the fragrance of a particular strain of beautifully smelling mung beans, as well as the scent of the Bassia latifolia flower and the smell of a tigress' billet-doux. (Curiously, mung beans also contain a compound which is found in rat vaginal secretions and acts as a sexual attractant.) Tigresses, as well as tigers, frequently mark their territories, jetting an aromatic milky, lipid-rich fluid upwards and backwards away from their bodies. The smell of this fluid is so strong that the Sanskrit word for tiger is vyagrciy a name derived from a verb root meaning 'to smell' (whether Pfizer, maker of the pharmaceutical Viagra which increases blood flow to the genitals, were aware of this remains unknown).

However, tigress marking spray is something of an enigma. Fatty acids, amines and aldehydes have all been identified in the fluid, and it is known that 2AP imparts its wondrous aroma, but its source and nature remain elusive. Although ejected under some pressure through the urinary channel, and possessing some urinary characteristics, this fluid is not urine. Neither is it an anal sac secretion. Its purpose is also unclear, although the frequency with which it is ejected and the marking strategies employed point to its role as a sexual signaller or territory marker. Do female tigers have an unknown accessory gland that is responsible for producing the fluids ejected in such a dramatic fashion? The image of tigresses ejecting an unknown milky, fragrant fluid pulls my mind immediately to that of a woman spurting opalescent prostatic fluid. Having inhaled deeply the exotic and highly erotic musky aroma of freshly ejaculated female prostatic fluid, I'm willing to place a bet that one function of this female genital secretion is of an olfactory and sexual nature. Perhaps tigresses have prostates too.

Speaking to the sisters

While the smell of female genitalia undoubtedly has an effect on the male of the species, the effects of eau-de-femalia do not stop there. Information about a female's reproductive status is of vital interest to members of her own sex, as well as the opposite. In fact, females in many mammalian species use olfactory signals from other females in order to help coordinate reproduction within a supportive social or physical environment. This is presumably because giving birth and rearing offspring in the secure company of friends, and at the best time of the year, is far more conducive to ensuring a species' survival than going it alone in a cold and dangerous place. Importantly, the first step towards co-ordinating the birth of offspring within a community is to synchronise a female's cyclic

THE STORY OF V

ovulation rhythms. That is, female scents force other females in a group to experience their oestrous or menstrual cycles together (menstruation occurs in Old World monkeys and apes, with some prosimians and New World primates also showing some blood loss).

A wealth of evidence highlights this amazing ovulation synchrony phenomenon, and how various genital fluids have an effect. For example, vaginal secretions are understood to mediate the menstrual synchrony shown in the reproductive lives of Old World primates such as crab-eating monkeys, chimpanzees and baboons. In the Holstein dairy cow, a mixture of urine and cervical mucus was found to exert cycle-shifting effects. The most detailed research to date has focused on the role of urine in entraining the oestrous rhythms of rodents, in particular those of rats and golden hamsters. Such work has shown that when females communicate their ovarian rhythms to other females the olfactory message they broadcast, and the effect it has, depends on the point they are at in their oestrous cycle - urine has the olfactory power to both phase-delay the cycle and phase-advance it, a system that allows for synchrony to arise more quickly. For female rats, pre-ovulatory urine odours shortened cycle lengths, while ovulatory urine lengthened them. On average, only three cycles are required for rat synchrony to develop (the rat's oestrous cycle is 4-6 days long).

Menstrual synchrony is also a common phenomenon in human females. However, although commented on for centuries, and demonstrated in women in 1971 in a classic experiment by psychology professor Martha McClintock, the scientific jury remained out until 1998 as to whether menstrual synchrony was truly an example of humans communicating their reproductive status by smell. It was further work by McClintock that gave the unequivocal answer at the turn of the century -yes, human females do communicate such genital information courtesy of their body odours. The ability of women to synchronise their ovulation rhythms and achieve a menstrual quorum was demonstrated in a study where the underarm sweat of human females at differing stages of their menstrual cycles was daubed on the upper lips of other women, and the effects on their menstrual cycles noted (underarm sweat was substituted for urine or vaginal secretions presumably to save the women's sensibilities).

The results were striking. Underarm secretions from the women's follicular phase (in the 12-14 days prior to ovulation) shortened the women's menstrual cycles (-1.7+0.9 days), whereas armpit sweat from the luteal phase (the days preceding ovulation and prior to the onset of menstruation) lengthened the menstrual cycle (1.4±05 days). Compounds in the axillary secretions, although perceived as odourless by the receiving women, advanced or delayed their menstrual cycle length. The

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

net result of this silent female chemical communication - menstrual synchrony.

Two separate points of interest have come out of this and other menstrual synchrony studies. First of all, ovarian synchrony is far more likely to occur if the women concerned are good friends with each other. Simply sharing the same physical environment is not necessarily enough to trigger entrainment. This can be understood in terms of what friendship signifies - safety- and when it comes to getting the timing right, with regard to reproduction, safety signals 'go'. Being in the company of enemies, on the other hand, or simply someone you're unsure of, spells out potential danger, saying 'beware, perhaps it's not a good idea to synchronise with these female foes, and subject your offspring to them and their kind'.

The second point of note from synchrony studies was that the females of some species appear to dominate ovarian synchrony groups - forcing other females to follow in their hormonal wake, as it were. Such an entrainer is known as a zeitgeber. The effect of such hormonally dominant females on the ovulatory status of their social sisters has been noted in several primate species, including marmosets and rhesus and talapoin monkeys, as well as in mice and hamsters, and the silver-backed jackal. In some mammalian species, such as the dwarf mongoose, only the dominant females in a group have reproductive cycles. Moreover, in some societies of species, one female will achieve complete ovulation suppression or quiescence of her sisters. For instance, the smell of a fecund queen bee is so potent that it simply stops other female bees' ovaries from developing.

The somewhat disturbing message from these synchrony studies is that feeling subordinate, like a second-class citizen, as a result of being put upon, stressed, unhappy in your environment or cowed by your social group, can delay or halt ovulation. Such ovulation suppression triggers, and not just those arising from female cohorts, are believed to underlie many cases of human female infertility in the twenty-first century's generation of overworked, underpaid and unappreciated women. Tellingly, stress-related infertility is reckoned to be responsible for 80 per cent of cases of female infertility.

The scent of a man

Considering the potent effect that the smell of a woman can have on a man, perhaps it will be heartening for men to hear that males hold sway too with their personal fragrances. The best studied male fluid, in this respect, is urine, in particular the urine of the male house mouse. Significantly, olfactory signals from the male mouse have an important role to play in regulating all three of a female mouse's major reproductive

THE STORY OF V

events - puberty, oestrous and pregnancy. For example, if a male mouse is introduced into a group of female mice, the majority of the females will be in oestrous three days later - pushed and pulled into ovarian synchrony by the scent of the male. His fragrance will also have an affect on prepubertal females. Two compounds in male mouse urine, iso-butyl amine and isoamylamine, are known to accelerate puberty. The olfactory effect of a male mouse on pregnant mice is even more dramatic. One whiff of the urine of a strange male mouse is enough to cause any recently pregnant mice to abort their developing foetuses. Incredibly, even extremely small amounts of urine evoke uterine growth in young female mice. Male smell-mediated effects are also seen in other rodent species.

Female rodents are far from alone in reacting genitally to the smell of the opposite sex. For as many women know, we are not immune to the scented charms of a man - be it his urine, breath, semen or sweat. Research shows that women who spent at least two nights in the company of men over a period of forty days had a significantly higher rate of ovulation than those sleeping alone. Other studies have revealed that women who are in the company of men three or more times a week tend to have shorter menstrual cycles than those who spend less time with men.

In a more detailed study of this effect on cycle length, male armpit sweat was dabbed on to the upper lips of women and the effects on their menstrual cycles monitored. The results were startling, and compare neatly with the female menstrual synchronisation study. The smell of a man appears to regulate and optimise ovarian function, as measured by the length of the menstrual cycle. Those women who had begun the experiment with irregular menstrual cycles - i.e., those whose cycle length was either longer or shorter than 29.5 days - found that their rhythms came closer to, or tied in to, this 29.5-day cycle length.

The effect of the smell of a man on a woman's ovulatory rhythm is important from a reproductive perspective, because female fertility is closely tied in with cycle length. Optimal fertility is associated with a menstrual cycle length of 29.5±3 days, while infertile women tend to have either short cycle lengths (less than or equal to 26 days) or long ones (more than or equal to 33 days). These irregular cycle lengths are far more likely to be anovulatory (that is, eggs are not released). The idea that women are far more likely to ovulate when they are around men, and intimate with them, rather than if they are not, makes perfect common sense. If there's no man around, why bother to ovulate and potentially waste an egg? Saving it for a more suitable date seems eminently sensible.

In an amazing coincidence, if it is that, 29.5 days, a woman's optimal fertility cycle length, is the moon's periodicity too - the time it takes the moon to shift from new to full and back again. Even more curiously, women tend to bleed in concert with the full moon and ovulate with the

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

new when enjoying the company of men. In contrast, celibacy, or being predominantly in the company of women, leaves menstruation tending to coincide with the new moon, and ovulation, if it occurs at all, with the full. Science has not yet been able to explain why the moon's periodicity matches a woman's reproductive periodicity precisely, or the links to ovulating and bleeding at the new and full phases of the moon. It is possible, however, that there is a biological connection, as many species use the phases of the moon to co-ordinate their reproductive cycles for optimum fertility. It is also now recognised that the uterine lining of a woman's womb fluctuates in its receptiveness to implantation, although it remains to be seen whether it is most receptive at new moon. Curiously, in gardening lore, the advice over centuries has been to sow seed when the moon is new.

Fascinating rhythms

There's one final way that a male can influence the functioning of a female's ovaries - and that is using his phallus to full effect. Fascinatingly, the physical stimulation of copulation can bring about ovulation. For many species this idea is nothing new. A variety of females, including insects and ticks and many mammals such as cats, rabbits, ferrets and mink, are reflex, or mating-induced, ovulators. These females do not ovulate unless they receive sufficient sexual stimuli - a mechanism which is a sensible way of conserving metabolic energy, with their energy channelled into growth and survival rather than unproductive oestrous cycles. So-called spontaneous ovulators, on the other hand, release their gametes apparently in response to regular and cyclic fluctuations in circulating hormone levels. Humans, rhesus monkeys, sheep, pigs, cows and rodents, among others, are spontaneous ovulators.

Ovulation is, however, still a bit of a mystery to scientists, in particular spontaneous ovulation. Why does each ovarian cycle affect only some eggs and not others? Moreover, the actual spark for ovulation - the event that forces a developing ovarian follicle to rupture and extrude, gently, its eggy contents - is still unclear. It is known that there is a build-up of pressure inside the developing ovarian follicle, and that hormones play a critical role in triggering the egg extrusion - specifically a simultaneous surge of luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) with the LH surge then triggering a cascade of enzymes, which catalytically break down the collagen casing of developed ovarian follicles. However a piece of the puzzle that is spontaneous ovulation is still missing.

Significantly, spontaneous ovulation is not as regular or rhythmic as previously supposed. Many women have irregular cycle lengths, and as noted, these are often anovulatory. Unfortunately, it's hard to say exactly

THE STORY OF V

how common anovulation is in women. Anovulatory cycles tend to go unnoticed because ovulation itself typically goes unnoticed by women (although some women, including myself, feel the deep, tight tension squeeze of mittelschmerz from an ovary). And as it's hard to say how many women's menstrual cycles are anovulatory, it's also difficult to say with any confidence how common ovulatory cycles are. Do women and other spontaneous ovulators release an egg every month? Very possibly not.

As a sidenote for any women listening out for mittelschmerz. First you need to locate your ovaries. The best way to do this is to place both hands palms down on your stomach, with the thumbs lying in a horizontal line and the thumb tips touching at a point directly over your belly button. The idea now is to make a downwards-pointing triangle with your hands -your thumbs form the top side of the inverted triangle, and where your index fingers come together is the lower apex. Finally, the points where the tips of your little fingers lie represent the position of your ovaries -under the skin, left and right. Knowing this makes it harder to miss mittelschmerz.

But to get back to sex and ovulation. Whether a woman has sex or not is a factor in whether she ovulates or not. And it seems that the more sex, the greater the likelihood of ovulating. Intriguingly, studies show that women experiencing regular sexual activity with men ovulated in over 90 per cent of their cycles, and had regular ovarian rhythms of around 29.5 days, whereas women who abstained from, or participated in only sporadic sexual activity, did not ovulate in over 50 per cent of their cycles. This physical phenomenon is also seen in other species that are classified as spontaneous ovulators. Copulation or stimuli mimicking copulation, such as vaginal or clitoral stimulation (in the case of a cow), has been found to cause ovulation to occur earlier than it would otherwise have done in sheep, swine, mice and rats amongst others. Tellingly, many unexpected human pregnancies are thought to flow from the erroneous belief that it's impossible to conceive a child late in a woman's cycle. As these parents know, sexual intercourse can all too easily stimulate ovulation and result in conception.

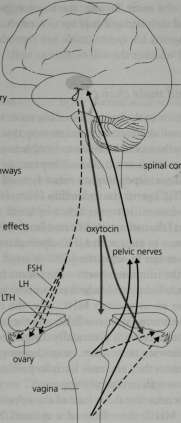

There are a number of ways by which the physical stimulation of sexual intercourse could exert an influence on the likelihood of ovulation occurring (see Figure 6.3). In many, perhaps most, mammals, it's thought that the surge of luteinising hormone (LH) associated with copulation and vaginal/cervical stimulation is a major factor in triggering gamete release. It's also possible that sex may have a more direct influence on the exact moment of ovulation, by inducing contractions of the ovary. Gamete release then occurs when the tension produced by contractions of the whole ovary overwhelms the tensile strength of the wall of the developed ovarian follicle and the pent-up fluid pressure within the fol-

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

pituitary

Key

Afferent nervous pathways

Possible autonomous nervous effects

Stimulatory hormonal effects

spinal cord

hypothalamus

Figure 6.3 The various pathways via which stimulation from sex can induce ovulation in mammals. Sexual stimulation either induces an egg to be released, or induces this event to occur earlier than it would have otherwise: LH lutein-ising hormone, FH follicle-stimulating hormone and LTH luteotropic hormone (adapted from Jochle 1975 and Eberhard 1996).

licle. These ovarian contractions have been documented in both reflex ovulators (in this case, cats) and in women (spontaneous ovulators).

If a male, by dint of his sexual technique, can induce a female's ovaries to contract, then this, perhaps coupled with the rise in LH levels, may trigger ovulation. Studies looking at a number of species reveal the importance of copulation style, length and frequency in inducing ovulation. Female prairie voles are more likely to ovulate if the male performs significantly higher numbers of thrusts. The degree of male stimulation can also significantly affect the number of eggs a female ovulates; with

THE STORY OF V

female rats, the more thrusts, the more eggs released. It seems that a male's sexual technique, if it is up to scratch, can influence both how a female transports his sperm inside her reproductive tract (as we've seen earlier), and whether she will ovulate as well.

Of mice and mate choice

Finally, a return to the nose. One of the most stunning discoveries about the role of smell centres on a phenomenon that was first reported in mice. Mice possess the enviable ability to be able to size up a potential mate on the strength of their smell alone. They can do this because mouse urine differs in odour depending on what type of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes the rodent has (histosis Greek for 'tissue'). What's more, the partners that mice select by smell are those that have MHC genes (alleles) that are quite different from their own. That is, mice sniff out and choose to mate with MHC-dissimilar partners. Why?

The answer lies in what the MHC is used for. MHC genes code for proteins in the immune system - the means by which an organism recognises, at a cellular level, whether something is dangerous or not. The more diverse an organism's MHC mix, the more able and flexible an individual's immune system will be, and the better their chances of recognising and dealing with potentially dangerous situations, such as infections. By following their noses, mice choose genetically complementary partners - mates they are more likely to produce healthy, viable offspring with - the strength in diversity approach.

Although mice use the odour of the opposite sex to sniff out a complementary MHC, the effects of a mouse's MHC are not just nasally directed. Studies show that, incredibly, the genitalia of female mice are able to recognise which sperm are more compatible with her than others on the basis of the MHC. Complementary sperm - those with a more dissimilar MHC - are transported more quickly within her reproductive tract than those sperm with similar MHC genes (as we saw earlier). Both a female mouse's nose and her genitalia work in harmony to sniff out Mr Right.

Other species, as well as mice, possess this remarkable ability to choose a mate guided by the MHC or something similar. Moreover, while the MHC plays an important role in immune function in vertebrates, invertebrates, bacteria and plants all have their own chemo-sensory mate attraction and screening systems in place. The genitals of the female fruitfly distinguish and act on differences in the genetic make-up of fruitfly sperm, sorting and selecting Which sperm to use to fertilise her eggs. Flowering plants have an elaborate recognition system in place, that will abort the interaction of stigma (female cell) with pollen (male cell)

THE PERFUMED GARDEN

if the pollen is too closely related to the female cell. Even broccoli has fifty different types of genes in order to avoid getting it together with a too-similar strain of broccoli.

Follow your nose