Some descriptions of how the uterus and cervix respond to orgasm come, strangely enough, from doctors who were treating 'hysterical' women with genital massage. In 1891, a Swedish physician, Lindblom, who at the time was providing 'pelvic massage' on a nearly daily basis, noted how orgasm altered the rhythm of uterus contraction. Others since then have noted the same - how orgasm increases the strength (amplitude) and occurrence (frequency) of uterine muscle contractions.

Intriguingly, it's now acknowledged that the muscular organ that is the uterus is actually never at rest. This structure - an upside-down pear or bull's head shape on the outside and an inverted triangle on the inside -exhibits steadily recurring rhythmic contractions and relaxations, with

THE STORY OF V

intervals ranging from two to twenty minutes, as Lindblom and others noted. During menstruation these contractions are stronger and more frequent, but can become spasmodic (indeed it's suggested that these spasmodic overactive contractions are the source of cramping period pain). Uterine contractions also increase during REM sleep, as women experience nocturnal erections, that is, increased blood flow to the genitalia.

The reasons why a woman's uterine musculature must pulse so rhythmically throughout her life are unclear. However, the uterus is a highly complex and astounding muscular structure - strong yet sensitive, as befits its remarkable role in reproduction. It has to be capable of supporting life, and have immense muscular force, able to push a bulky child through a confined space. Not surprisingly, uterine muscle is one of the strongest muscles of the body. Perhaps it is because of its important role in reproduction that uterine muscle can never afford to be completely at rest and risk losing its efficacy. It's possible that this is also why a woman's Fallopian tubes continually contract and relax throughout her life (about three contractions per minute), and why a woman's vaginal musculature does too. Spontaneous vaginal contractions originate from the cervical end of the vagina and are reported to occur every eight to ten minutes (in the resting, sexually unstimulated state, and in pregnant and nonpregnant women).

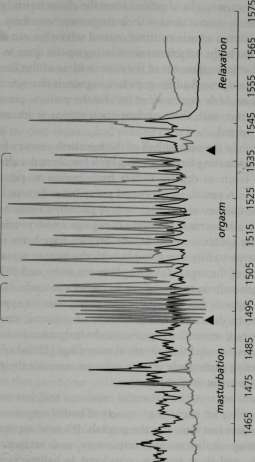

The muscular moment

While a woman's genitalia are never completely quiescent even when unaroused, on orgasm their muscular response is dramatic. Powerful involuntary rhythmic contractions and relaxations shudder throughout this muscular organ, which consists of both smooth and striated muscle. Indeed, it's now appreciated that in women the point of orgasm can be said to be characterised by the rapid forceful and rhythmic muscle contractions of the uterus, cervix, vagina, urethra, prostate and anus (Figure 7.4 shows how these orgasmic contractions affect vaginal and anal pressures). If orgasm occurs, then a woman's pelvic muscles are rippling in concert. Orgasm does not appear to occur without this physical muscular reaction. This, it is suggested, is the physical basis of orgasm. This glorious vibration phenomenon of genital muscle contractions and relaxations is the hallmark of an orgasmic happening.

Scientific studies of female orgasm show that differing numbers of pulsatile pelvic contractions can happen. Some reports mention between five and fifteen contractions at about one-second intervals, others four to eight times at intervals of 0.8 of a second. However, there is no standard, and contractions can be regular or irregular, and both. Curiously, research

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

n >- O Oj QJ £

T <U

5. o3

1^

a oo o as

<H-i ^

I|

O 43 ■5 O

Oh g

00 o

a da

U

c/5 00

3 ° to O 2h 43

— s

cd U3

~§ S

3* ■'-'

,—, <n

§>« g.fc

o i_

.,_, <u O Oh

J!

3 to o §

*■«

0 ? H wd ui ajnssajd uo|pej;uoD

So £ O .2

** 8i B

3 to oo <tf

£ 6

THE STORY OF V

suggests women canjbe identified from the characteristic pattern of their pelvic muscle contractions - their frequency, waveform and muscular force. Rhythmic muscle contraction and relaxation can also occur elsewhere in the body, sometimes shuddering up the spine to the head in an orgasm that is reminiscent of the eastern ideas of the Kundalini serpent climbing the spine. And for men too, orgasm is characterised by muscle contractions. Male contractions involve the urethra, prostate, testes and anal sphincter, with three or four contractions at intervals of 0.8 of a second reported.

Research in the second half of the twentieth century has also thrown up some fascinating facts regarding both female and male orgasm. While the time taken to orgasm differs from person to person, and varies depending on mood, scenario and many other factors, in a laboratory setting the quickest recorded time to orgasm by a woman was just fifteen seconds. It also seems that lengths of orgasm are very variable. In studies, the muscle contractions of female orgasm have been reported to last from thirteen to fifty-one seconds, with the women signalling their own experience of the orgasm as being between seven and 107 seconds. Male orgasm generally lasts around ten to thirteen seconds. Meanwhile, some research suggests that having stronger pelvic muscles appears to enhance the intensity, duration and occurrence of orgasmic contractions. And intriguingly, it seems that orgasms can be truly consciousness-altering, as studies have revealed that electrical recordings (EEGs) of women's brain waves during particularly intense orgasms resemble the patterns seen in people who are in deep meditation.

Orgasms are complex, powerful creatures, and, not surprisingly, they are responsible for triggering a variety of bodily responses, not just muscular and not just aimed at the genitals. It's now appreciated that they elicit strong cardiovascular, respiratory and endocrine (hormonal) responses, and these too are considered as hallmarks of orgasm. For example, the extragenital responses of both women and men typically include a doubling of the heart and respiratory rate, with blood pressure commonly climbing to a third above normal, and pupils dilating. Many people vocalise their shocking, searing, completely overcoming sensations, and orgasm faces' are also distinctive. An intense rosy red sex flush across the chest is observed in three-quarters of women, although this is not as common in men (25 per cent).

The story of oh, oh and ohhhl

Multiple orgasm, the ability to experience one orgasm after another after another, has also come under scrutiny. In the laboratory, the record for the greatest number of orgasms in an hour goes to a woman who, it is

274

i

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

said, achieved a spectacular, mind-blowing and eye-watering 134. Not surprisingly, perhaps, how orgasmic a woman is also seems to have a knock-on effect on the time it takes her to come. In a study comparing the time to orgasm of women who are multiply orgasmic with singly orgasmic women, it was observed that, on average, multiply orgasmic women took eight minutes to reach orgasm, whereas singly orgasmic women took twenty-seven minutes. Interestingly, the average time to second orgasm for the multiply orgasmic women was only one to two minutes, as if the first orgasm had primed their bodies. After the second orgasmic event, subsequent orgasms tended to take even less time - thirty-second intervals between orgasms were not uncommon and a few fifteen-second intervals were recorded.

The most immediate difference between the two sexes' orgasms is that women are far more commonly multiorgasmic than men. This is typically because in order to enjoy orgasm after orgasm, men must learn to develop and strengthen their genital musculature, thus enabling them to have greater control over ejaculation. Indeed, if men wish to, they can use their pelvic muscles to stop themselves from ejaculating on orgasm. Men who are capable of separating these two processes report that they are then more likely to enjoy multiple orgasms. Moreover, it should be said that although ejaculation is classically associated as an integral part of male orgasm, strictly speaking this is incorrect. Ejaculation and orgasm are two separate physiological mechanisms. While orgasm is a perception accompanied by motor or muscular activity, ejaculation is just a reflex, a motor pattern that can occur independent of the brain (for example, in a spinal-cord-transected human or animal).

There is some good news for men, though, on the multiple orgasm front. Although male multiple orgasms are typically a result of utilising strong pelvic muscles to stop ejaculation occurring, science has also discovered a small group of men who experience multiple ejaculatory orgasms - that is, they are multiply orgasmic and ejaculate with every orgasm too. These men fall into three groups - some have always enjoyed multiple ejaculatory orgasms, others have taught themselves how to, and for others it has happened serendipitously. In one laboratory study, a thirty-five-year-old man enjoyed six orgasms with six ejaculations, with a period of thirty-six minutes between his first and last orgasm (the first orgasm came eighteen minutes after he started stimulating himself). Despite these heroic efforts, women still come out on top in terms of multiple orgasms. As we've seen, the highest number of female orgasms recorded in a laboratory setting was 134, whereas the top score for men in the same length of time was sixteen. Strangely, the ratio of these figures almost mirrors that given by Teiresias, in his answer regarding who has the greatest pleasure during sex: 'thrice three to women, one only to men'.

THE STORY OF V

An innate capacity?

One of the most startling recent discoveries about the characteristics of orgasm is that these muscle contractions are one of the first sensations humans ever experience. That is, incredibly, both female and male foetuses orgasm in the womb. The following description of female orgasm in utero is from the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and was reported by two Italian doctors during a routine pre-birth ultrasound scan.

We recently observed a female fetus at 32 weeks' gestation touching the vulva with the fingers of the right hand. The caressing movements were centred primarily on the region of the clitoris. Movements stopped after 30 to 40 seconds and started again after a few minutes. Furthermore, these slight touches were repeated and were associated with short, rapid movements of pelvis and legs. After another break, in addition to this behaviour, the fetus contracted the muscles of the trunk and limbs, and then clonicotonic movements of the whole body followed. Finally, she relaxed and rested. We observed this behaviour for about 20 minutes. The mother was an active and interested witness, conversing with observers about her child's experience.

The authors concluded their astonishing account of in utero female orgasm by saying: 'The current observation seems to show not only that the excitement reflex can be evoked in female fetuses at the third trimester of gestation but also that the orgasmic reflex can be elicited during intrauterine life.' Perhaps it's not surprising to hear that male foetuses too have been found pleasuring themselves in the womb. Indeed, it's not unusual for parents-to-be to see their embryonic son grasping his erect penis in utero, while moving his hands in a repetitive masturbatory fashion, for up to fifteen minutes at a time.

How come humans have such an extraordinary capacity for orgasm? One answer is thought to lie with the number of sensory nerve pathways that can play a role in triggering human orgasm and pleasurable sensations. Orgasms don't appear out of nowhere, rather they must be built up to (and curiously and wonderfully, this orgasmic process can be as pleasurable as the orgasm itself). Sexual arousal typically occurs as a result of the activation of various nerves. This nerve stimulation (perhaps from caressing or kissing or more) then causes a further build-up of excitement and arousal until a level is reached that triggers a different, relatively high threshold motor system - and it is then that explosive, rhythmic muscular contractions are felt. Rhythm, the timing of the stimulation, is also a crucial factor in creating orgasm, as rhythm aids in recruiting more and

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

more neural elements to fire together in what will be ultimately orgasmic harmony.

Typically when orgasm occurs, it is a result of one or more of three genital nerves being activated. These are the pudendal, pelvic and hypogastric nerves. Significantly, these nerves are all genitospinal nerves, meaning they run from the genitalia and then project into a person's spinal cord, with each nerve system having a different level of entry into the spinal cord. This means that in women, if you stroke the clitoris and the sensitive skin (including labia and perineum) surrounding the opening of the vagina, then you're likely to be firing off the pudendal nerve. But if you stimulate the vagina, urethra, prostate and/or the cervix, it's the pelvic nerves that you're affecting. However, there is some overlap, as the hypogastric nerve transmits sensory stimuli from the uterus and cervix, as well as some vaginal sensation. There is also some overlap of the sensory fields of the pelvic and hypogastric nerves in the cervix. In men, the pudendal nerve innervates penile and scrotal skin; the hypogastric nerve transmits sensory stimuli from the testicles and anus; and the pelvic nerve is thought to innervate the prostate.

Variety is the spice of life

Two of the most controversial issues surrounding female orgasm are whether there is more than one type of orgasm, and whether one type of orgasm is better than another. The answer to the latter question is, I suggest, that an orgasm is an orgasm is an orgasm. If it's pleasurable enjoy it. And don't be swayed by the fad of the day. Do it your way, the way that pleasures you the best. But what about the first question? Is there such a thing as a vaginal orgasm, rather than a clitoral or a G-spot orgasm?

The answer, strictly speaking, is yes, but there's more to it than that. Fantastically, in women, because of the different sensory pathways involved in innervating the distinct areas of female genitalia, orgasm can and does come in a glorious variety of ways. Just the cadence of gentle clitoral caressing alone can cause orgasm, but so too can vibratory stimuli focusing primarily on the urethra or prostate (G spot), or singling out the cervix for pulsatile thrusting stimulation, or simply squeezing the vaginal muscles. This appreciation of the nerve pathways underlying orgasm also explains why anal intercourse is an orgasmic activity for women - as the hypogastric nerve also innervates the rectum. And if I was hellbent on classifying, I'd say that the first orgasm was clitoral, the second a G spot, the third cervical, the fourth vaginal and the fifth anal. Importantly, though, when it comes down to it, most women will experience a blend of the above, as in practice it is extremely

THE STORY OF V

unlikely that just one nerve pathway will be stimulated. So most orgasms are, in fact, a delicious blend, and what could be wrong with that?

Interestingly, one of the most significant discoveries regarding female orgasm stems from a greater appreciation of the nerve pathways involved in orgasm. While it has been known since the start of the 1990s that the pudendal, pelvic and hypogastric nerves transmit genital sensations, and are therefore key in triggering female and male orgasm, it has only recently been recognised that in the female, another nerve pathway plays an important role. Pleasingly, it seems that, for women at least, there are more ways to orgasm than previously supposed.

The first clues that there may be more to understanding how female orgasm can occur came from anecdotal reports in the 1960s and 1970s of women with 'complete' spinal cord injuries (SCI) who nevertheless spoke of experiencing orgasms during their sleep. (Criteria of complete SCI include being unaware of pinpricks or light touch below the level of injury, and also not having any voluntary movement or rectal sensation below this level). Dubbed 'phantom orgasms' by the medical profession, these 'orgasmic' feelings experienced by women with complete SCI were, for the major part, dismissed.

However, evidence pointing to another nerve pathway to orgasm mounted. Other women who were paralysed, with no feeling below the breast, also related how they appeared to have retained some awareness of their internal genitalia, speaking of feeling an 'abdominal glow' during sexual intercourse or of feeling the cramping uterine sensations of menstruation. Reports of such genital sensations posed an intriguing puzzle for the medical community - all,known orgasmic and genital sensory pathways involved genitospinal nerves, therefore injuries to the spinal cord would interrupt their input, ultimately denervating a person's genitalia. Without any known nerves innervating their genitalia, how could women with complete SCI perceive and enjoy orgasm? In part because of any physical evidence to the contrary, these reports continued to be dismissed as phantoms or fancies of female imagination.

However, during the 1990s, the anecdotal reports of female orgasm and genital sensations despite a lack of functioning genitospinal nerves were backed up by evidence from scientific studies involving women with complete SCI. These pioneering studies showed that, for these women, despite their injuries, vaginal and cervical stimulation with a genital stimulator elicited both perceptual and autonomic orgasmic responses. That is, the women perceived themselves as experiencing orgasm - indeed, their descriptions of orgasm are indistinguishable from those of able-bodied women. They also expressed physical awareness of the genital

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

stimulator, describing the sensation at the cervix as 'a nice feeling of suction' and as 'deep in the abdomen'. Vaginal stimulation was detailed as 'feeling deep inside'. To add to this, characteristic involuntary responses to orgasm (autonomic responses) were observed too - widening of the pupils, increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure. These women were experiencing orgasm, but how?

The wanderer returns

The answer lies with the vagus nerve, the wandering, seemingly whimsical nerve which, courtesy of its many branches, innervates many of the body's major organs. The vagus, named from the Latin for 'to wander', lives up to its monicker, emerging from the brain stem into the neck and then weaving and wending its way round the body, passing through the chest cavity - heart and lungs - branching out to the pupils of the eye and the salivary glands, connecting with the abdomen, the intestines, the bladder and the adrenal glands, yet - crucially - neatly bypassing the spinal cord. Finally and fortuitously, the circuitous path that the vagus nerve system takes through the body ends with it anchoring itself in the uterus and cervix.

Crucially, it is because of the vagus' genitalic connection in the uterus and cervix that women with complete SCI can still perceive vaginal and cervical stimulation and enjoy the resulting pleasures of orgasm. It is vagus nerve fibres that are transmitting genital sensations to the brain, and because the vagus bypasses the spinal cord, this system is not affected by spinal cord injuries. (It's estimated that up to 50 per cent of women with spinal cord injuries are able to achieve orgasm.) Whether or not the vagus operates in a similar manner in men is as yet unclear, although there are hints that it may.

As a result of uncovering the role of the vagus nerve in transmitting genitosensory stimulation, and generating female orgasm, some scientists are starting to rethink ideas about genital sensation, orgasm, and the origins of orgasm. The vagus, one of the cranial nerves, is of major significance to species, starting with the most primitive vertebrates, right up to mammals. It is intimately involved in many basic bodily functions -breathing, swallowing, vomiting and digestion. Significantly, it is also, in evolutionary terms, ancient, and has been around since the early primitive vertebrates, such as the lamprey. Taken together, these facts - the vagus' ubiquity, history and present day-genitosensory innervation and orgasm role - suggest that the vagus may represent a primitive system for sensing the genitals and experiencing the muscular contractions and relaxations of orgasm.

THE STORY OF V

Seeing in the dark

We've already seen that the vagina is an incredibly intelligent organ -capable of sorting and selecting sperm with a remarkable specificity. But can you credit that the vagina has extra sensory perception (ESP) too? Startlingly, the discovery of the role of the vagus nerve in human female orgasm suggests that it does. In the studies investigating how women without functioning genitospinal nerves (complete SCI) perceived genital sensations and orgasm, two distinct groups emerged. The first were women who stated that they could consciously feel the genital stimulator in their vagina or against their cervix, and it was this sensation, transmitted by the vagus nerve, that then triggered their orgasms.

However, there was a second group of SCI women who were orgasmic too. And orgasm in these women was more perplexing. These women experienced orgasm with the genital stimulator in their vagina or against their cervix, despite the fact that they did not consciously perceive any physical sensation from the genital stimulator or their genitalia. Somehow, though, their vaginas sensed the applied vibrating genital stimulation (even if they didn't consciously) and responded orgasmically. How can this be so? One suggestion as to how this might occur is that the vagina may be capable of experiencing the phenomenon known as 'Hindsight'.

Blindsight is the term traditionally applied to the ability of some people with lesions in the visual cortex to respond appropriately to visual stimuli without having any conscious visual experience. That is, they respond as though they can see, even though they cannot see. And in some of the women with SCI, they respond as though they can feel the genital stimulation, even though they cannot feel it. So is this female orgasmic experience the equivalent in the female genital system of blindsight in the visual system? Moreover, is it the input of the vagus nerves that produces genital blindsight? With research into vaginal blindsight still at a very early stage, perhaps it's not surprising that the jury is still out on these questions. Other questions remain to be answered too. Vaginal blindsight appears to suggest that the female genital orgasmic response is particularly robust. Why should this be so? Is female orgasm or the ability of female genitalia to respond in a characteristic muscular fashion essential for evolution or successful sexual reproduction?

Curiously, the human capacity for orgasm is not limited to arousal stemming from stimulation of genital nerves, be it the pudendal, pelvic, hypogastric or vagus nerves. Orgasm can also be triggered as a result of stimulation of non-genital nerves too. Non-genital orgasms - orgasms resulting from erotic and rhythmic stimulation of the breasts, mouth, knees, ears, shoulder, chin and chest - all these have been recorded in a

280

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

research setting. Pioneering sex researchers Masters and Johnson observed back-of-the-neck, small-of-the-back, bottom-of-the-foot and palm-of-the-hand orgasms, and chose to view the whole body as a potentially erotic organ. Both women and men with spinal cord injuries anec-dotally report that stimulation of the hypersensitive skin zone that develops at or near the level of the injury to the spinal cord is capable of eliciting orgasm.

Laboratory investigations of these orgasmic episodes reveal that orgasm is indeed occurring. In one case, use of a vibrator on a woman's hypersensitive skin zone at her neck and shoulder resulted within several minutes in a characteristic increase in blood pressure, and an orgasm described as a 'tingling and rush'. The woman added how her 'whole body feels like it's in my vagina'. And while such non-genital phenomena demonstrate that orgasms can be produced by sensory stimulation of the rest of the human body, as well as the genitalia, other studies involving women show how, incredibly, imagery alone can be sufficient to trigger orgasm. For this group of women, physical stimulation was not needed to induce orgasm; their minds alone, thanks to fantasy, could take them there - despite being in a laboratory.

Of animals and orgasm

The fact that the phenomenon of female orgasm in humans is so flexible and robust raises the question of whether other females of other species are orgasmic. And although initially disputed and highly controversial, it is now generally accepted that female animals are capable of experiencing orgasm. There is, in fact, a wealth of information showing that many species undergo precisely the same physiological responses that humans do when they come. For example, in both female and male primates, powerful, rapid and rhythmic genital muscular contractions underpin orgasm. Studies show that in many female primates, the signature muscle contractions that shudder through the uterus, vagina and anus during copulation or masturbation typically go hand-in-hand with other physiological responses, such as vaginal engorgement, clitoral erection, tension in the muscles of the body, abrupt heart rate increases and piloerection (hair standing on end). These genital contractions are also associated with behavioural responses, such as copulation calls (rhythmic vocalised expirations), a characteristic look-back and reach-back at the male reaction, and finally, what is known as the climax, or 'O' face - a distinctive facial expression with the mouth opened in an 'O'.

Amazingly, in female stumptail macaques, detailed measurements of uterine contraction patterns reveal them to begin to change markedly (increasing in intensity and pressure) up to eight to ten seconds before

THE STORY OF V

the climax face is shown. These genital contractions then continue to contract and relax for up to fifty seconds. Significantly, the female's climax face occurs when the contractile force of the uterus reaches its peak. This open-mouthed facial expression can then last for up to thirty seconds, disappearing before the macaque's pelvic muscular contractions ebb away to pre-orgasmic levels.

A wealth of other female animals display an orgasmic muscular reflex during and after sexual activity, and also when indulging in non-reproductive sexual activities - be they manipulating their own genitalia or those of fellow females. Following genital and urethral stimulation, female rats display a rhythmic coitus reflex of their pelvic muscles, just like male rats do. Cows respond orgasmically to massage of their clitoris, with muscular contractions of their uterus, cervix and vagina. After only a few minutes' clitoral stimulation, a cow's cervix can be observed gaping open and moving. The domestic cat exhibits an orgasmic genital muscular 'after-reaction', as well as screeching her sensations, while elsewhere in the farmyard, a sow's vagina (with its spiral-shaped cervix) is seen to grasp the male pig's penis during orgasm, as she apparently grinds until she's satisfied. Horse breeders comment on the orgasmic' muscular coital reactions of mares.

In fact, it appears impossible to find an internally fertilising female who does not respond to sexual stimulation with characteristic genital muscle contractions. Mice, guinea-pigs, dogs and more have all had their powerful vaginal contractions detailed in the scientific literature. One study looking at female dogs notes, with interest, how the vaginal muscle spasms of the bitch were so strong and violent that they 'could obliterate the urethral lumen of the penis were it not protected by the os penis [the penis bone]'. Indeed, it's suggested that the bones in some males' phalluses, like primates and dogs, are there to prevent penile injury, such as urethral damage, as a result of the female's crushing and potentially pulverising genital contractions. And finally, as previously highlighted, powerful rhythmic movements of the female's pelvic musculature are a key component of sexual activity throughout the insect kingdom too. It seems that genital muscle contractions are a crucial component of female orgasm, and as we'll see, there is a reason for this.

Do animals enjoy orgasm?

But first, a quick comment on animals and orgasm. Do animals enjoy and take pleasure in the vibrations of orgasm? Although many people would perhaps rather presume that other species do not delight in orgasm there is plenty of evidence to suggest that they do. Many mammals show enjoyment of sexual activities, including copulation, same-sex play and

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

masturbation (both in the wild and in captivity). Females not only fondle their external genitalia (as previously detailed), they also find novel ways of stimulating themselves internally. Female chimpanzees and orangutans insert objects, such as leaf stems and twigs, into their vaginas, moving them repeatedly inside, adding extra lubrication by licking them, and sometimes rocking backwards and forwards on their makeshift sex toy. Female chimpanzees have even been observed carefully biting pieces of plant to the particular length required for insertion and stimulation. In the laboratory, witness the orgasm face of the female stumptail macaque as her genital contractions peak. Or how about the study that revealed how, during thrusting vaginal stimulation, and at the point of orgasm (characterised by peak pelvic contractions), primate females reached back in order to increase the pressure the genital stimulator was applying to their genitalia. It seems they wanted more pleasure.

Astonishingly, female dolphins are equally inventive in their search for internal genital pleasure. Female-female dolphin sex play can include the insertion of one dolphin's fin or tail fluke into the female partner's genital slit. Beak-genital propulsion is another variant on this, whereby one dolphin inserts her snout or beak into the genital slit of another female, simultaneously stimulating her while, swimming, she propels her forwards. Female dolphins have also been observed using their vaginal muscles to carry small rubber balls, which they then rub and squeeze their genitalia against.

The function of the female orgasm

Humans enjoy it, and animals do too. And as we've seen, it's underpinned by characteristic contractions of the genital muscles. But just what is the function of the female orgasm? While female sexual pleasure, be it orgasmic or simply highly stimulating, has in recent centuries been read as having no role to play in sexual reproduction, this, I suggest, is not strictly correct. Significantly, there are a variety of reasons why this is the case. First of all, in the majority of female species, a specific degree of female genital stimulation is essential for successful sexual reproduction to occur. As previously highlighted, the design of female genitalia effectively dictates what a male must do if he is to have a chance of gaining entry to her body, and the opportunity of access to her eggs. Moreover, once inside her, he must then fulfil a whole new heap of genital requirements if the female is to respond in a way that enables his sperm to have the opportunity of having an encounter with one of her eggs. If he does not satisfy these requirements laid down via the design of her vagina, then she has the power to eject, digest or destroy his sperm.

For males, this situation means that if their sexual performance does

THE STORY OF V

not come up to scratch - if they do not provide the requisite level of female genital stimulation at the right time and in the right place, both externally and internally - then their opportunity to father offspring will fall by the wayside. They may not get a second chance either, because as most females mate with multiple males, another male will soon take their place. More starkly, if a male never learns the right routine with which to pleasure females of his species then it's very unlikely that he will ever reproduce successfully. In the animal and insect kingdoms, it's never a sensible sexual strategy to enter without permission, dump your sperm quickly and leave. This is why applying the 'correct' level of female genital stimulation, which in some cases may be orgasmic, is essential for successful sexual reproduction.

Some mammals, such as rabbits, cats, ferrets, minks, squirrels and voles, provide a very clear example of the specific degree of female genital stimulation that males must provide if they are to reproduce successfully. These mammals are reflex or mating-induced ovulators - that is, ovulation, the release of an egg, occurs as a reflexive reaction to a requisite level of genital stimulation. In this way, reflexive ovulation is akin to male ejaculation, the reflexive release of semen. In female prairie voles, for example, the likelihood of ovulation is related to the number of vaginal thrusts the female feels (the more she receives, the better the chance of ovulation occurring).

For rabbits, some of the necessary female genital stimuli to trigger ovulation are known. First of all the male rabbit must perform up to seventy rhythmic constant-amplitude, high-frequency extra-vaginal thrusts (too low a frequency and a lack of rhythm does not get results). Vaginal entry is dependent on this particular rhythmic routine, and this stimulation may also begin the cascade of hormonal events necessary to trigger the release of an egg. Once permitted access to a doe's internal genitalia, cervico-vaginal stimulation must then be sufficient to trigger the necessary hormonal conditions for ovulation to occur. Taken as a whole, the specific choreography of rabbit sex shows the importance of the male stimulating the female both internally and externally- providing both foreplay and fucking, if you will.

Why human ovulation is not strictly spontaneous

Many other mammalian species, such as cows, pigs, rats, sheep, mice, hamsters and humans, are termed spontaneous ovulators, that is, they normally ovulate in response to cyclical changes in hormone levels. However, the crucial word here is normally. Cows, pigs, rats, sheep, mice, hamsters and humans are also all capable of ovulating reflexively, i.e., in response to a specific degree or type of genital stimulation. Thus sexual

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

choreography in these species is also crucial for males who want to optimise their reproductive success. (Stimulation prompting ovulation in these species is commonly genital, but it can also be olfactory, ocular, acoustic or emotional.) In female cows, ovulation can be brought on by sufficient stimulation of the clitoris, while cervical stimulation hastens the surge of luteinising hormone (LH), which stimulates ovulation.

Studies involving artificial insemination in cattle have also highlighted that genital stimulation can help cows conceive. Put plainly, the effectiveness of artificial insemination in cattle is markedly increased if accompanied by rectal manipulation of the uterus. If a cow does not receive 'enough' genital stimulation then conception rates fall. This same situation occurs with sheep. If animal breeders wish to increase conception rates in ewes significantly, they employ a vasectomised ram to genitally pleasure the female. Simply placing semen in a sheep's vagina is not sufficient to ensure successful sexual reproduction (or a profitable artificial insemination business).

The reproductive need for specific levels of genital stimulation is even clearer with female rats. Here, the number and rhythm of intromissions (the number of times the male's penis is inserted into and enveloped by the vagina, and the timing in between the intromissions) before ejaculation is directly related to whether or not the female becomes pregnant. If the number of intromissions is less than three, then she will not conceive, even though the male deposited his ejaculate (the preferred number of intromissions is between ten and fifteen). Significantly, his failure to father offspring with her is directly related to the level and rhythm of genital stimulation he provided.

Some details of the neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying this rodent situation are understood. It's known that the vaginal stimuli from intromission are picked up in the female rat by the pelvic nerve, and if enough of this particular stimulus is received, it triggers the secretion of the hormone prolactin, which in turn causes ovarian progesterone to be secreted. It is this secretion of progesterone which stimulates uterine growth, preparing it for the implantation of a fertilised egg. Not enough rhythmic vaginal-cervical stimulation equals not enough progesterone secreted equals an unresponsive uterus and the failure of a potential pregnancy. The degree of male stimulation can also significantly affect the number of eggs a female ovulates - the more thrusts female rats receive, the more eggs released.

As previously discussed, women too are not immune to the hastening effects on ovulation of intense genital stimulation and orgasm. However, it remains unclear whether it is the gonadal hormonal surges post-orgasm and genital stimulation that can elicit ovulation, or whether it is orgasmic muscular contractile forces shaking already primed and highly tensile

THE STORY OF V

ovaries that can cause ovulation to occur earlier than it would have done. Perhaps both. As the vagus is among the nerves that innervate the ovaries, there is also the possibility that vagally induced orgasm may well have a knock-on effect on the ovaries and egg release. Plus, smooth muscle is a constituent of ovarian tissue, and so compounds that act on smooth muscle may also affect the timing of egg extrusion. The mechanics remain to be determined, although it is clear that orgasm can and does influence the timing of ovulation in women. Curiously, in the 1800s, the moment of ovulation - when the ovarian follicle is at its most swollen and poised to extrude its contents - was known as Vorgasme de Vovulation, z. phrase that ties in with the original Greek meaning of orgasm - to grow ripe, or swell. And elsewhere in nineteenth-century medical writings, orgasm' implies extreme turgidity or an organ under a great state of pressure.

When the earth moves

As well as affecting the timing of ovulation, the number of eggs released and the viability of uterine implantation, there are other ways in which female genital stimulation and/or orgasm can influence the outcome of sexual intercourse. As we have seen, orgasm and/or genital stimulation has a very striking effect on a female's genital musculature - namely, increasing the intensity and frequency of rhythmic, rippling contractions and relaxations. These characteristic genital muscular vibrations are present in a vast variety of internally fertilising species, perhaps all, from women and chimpanzees, cows and sheep, rats and mice to chickens and dunnocks, bees and beetles. And as previous chapters have demonstrated, sperm transport is primarily a female-dominated affair.

What is significant in terms of sexual reproduction is that it's now increasingly recognised that the contractile forces wielded by a female's genital musculature play a critical role in how she transports sperm through her reproductive system. If the internal vaginal and uterine pressure is just so, and the pelvic muscle contractions are tuned just right, say with contraction waves running from the cervix to the ovary, plus the cervix is poised to dilate at the critical moment, then it is far more likely that any sperm present will be pulled towards a female's ova rather than being ferried away. Some studies, most notably in cows and pigs, have highlighted just how this can work.

Throughout the ovulation cycle of cows and pigs, spontaneous myometrial (uterine muscle) contractions occur. Outside of oestrus, these contractions start at the tubal end of the uterine horns and run towards the cervix - that is, contractions move against any sperm present. However, during oestrus, this pattern of muscle contraction reverses, and contractions start at the cervix and run towards the Fallopian tubes. Any

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

sperm present at this point in the cycle are thus effectively placed on a moving walkway running direct to the female's eggs. Female orgasm during oestrus, courtesy of the increase in strength and frequency of muscle contractions, acts to enhance this directional effect, increasing the likelihood of sperm being retained and conception occurring.

Research in other species also underlines how genital stimulation and/or orgasm affects these sperm-transporting muscle contractions. In the mare, the stimulus of mating results in forceful genital contractions and a strong negative uterine pressure, which results in a forceful 'insuck' of fluid from the vagina into the uterus. In hamsters, what were described as 'dramatic vaginal contractions associated with mating' resulted in the rapid transport (within ninety-one seconds) of sperm into the uterus. In mice, high cervical tension is associated with reduced amounts of semen flowing back out of the vagina. In rats, sperm transport does not take place unless a female receives more than two intromissions.

On the other hand, if not enough stimulation is applied prior to ejaculation, sperm can be summarily digested or ejected. As noted, female damselflies tend to retain the sperm of males who provide more stimulation, and expel the sperm of males who provide less (average forty-one minutes versus seventeen minutes). Significantly, research has shown that stimulation of the sensillae that line the female damselfly's reproductive tract does indeed result in the reflex contraction of the muscles of her sperm storage site. In sheep, stressful, as opposed to pleasant stimuli have been shown to influence sperm transport too, reducing the numbers of sperm reaching the uterus.

Does it work for women too?

And what about women? Well, in women, studies show that there are two important factors in determining how many of a man's sperm a woman transports and retains. These vital factors are whether or not, and when, the muscular contractions of orgasm occur. Interestingly, research has revealed that if a woman comes any time from one minute before the man to three minutes afterwards, then she will retain more sperm than if she had not come at all, or if she came much earlier or much later than him. This difference is estimated to represent about ten million sperm.

The sperm transport and retention effect is thought to come about because at the onset of female orgasm, muscular contractions cause intrauterine pressure to increase markedly, together with a rise in vaginal pressure. However, immediately post-orgasm, intrauterine pressure drops sharply, creating a pressure gradient between a woman's uterus and her vagina. Hence, if sperm are present in a woman's cervical mucus when

THE STORY OF V

she comes, the suction created by this pressure gradient results in the more rapid transport of sperm into her uterus. The cervix and its mucus play an important role in this scenario, as during the build-up to orgasm the cervix dips down further into the vaginal chamber, extruding mucus from its external os. If sex is taking place during a woman's fertile period, this mucus is capable of sequestering sperm in its shimmering folds. Moreover, post-orgasm, the sharp changes in genital pressure result in bodyguard mucus (and its sperm load) being sucked back through the cervical canal and up into the uterus.

The pituitary hormone oxytocin is believed to be at least part of the reason why enough genital stimulation and orgasm results in genital muscle movement and sperm transport. Oxytocin, amongst many other effects, has the ability to stimulate the contraction of smooth muscle. When it comes to female genitalia, this ability is of particular importance, because a female's genitals - including the uterus, cervix, ovaries, vagina and prostate - contain smooth muscle. In women, genital stimulation causes levels of oxytocin to rise, and as arousal increases, so too does muscular tension. Surges of oxytocin are then strongly associated with the strong uterine and vaginal muscular contractions of orgasm, the gaping or dilation of the cervical os, and the widening of a person's pupils. Significantly, the intensity of muscle contractions during human female (and male) orgasm are highly correlated with levels of oxytocin.

In many other mammals too, including cows, rabbits, goats, and ewes, rapid increases in oxytocin are accompanied by forceful uterine or cervical muscle movements. Indeed, oxytocin, from the Greek for 'swift birth', is named after its most dramatic effect on female genitalia — the massively powerful uterine smooth muscle contractions of labour. This striking parturition response to oxytocin is, of course, why pregnant women are often advised to indulge in passionate orgasmic sex. Milk ejection, or letdown, is another of oxytocin's stunning effects. Incredibly, cow's vaginas are so responsive to genital stimulation that blowing air into their vaginas is sufficient to elicit this response, and, fantastically, increase milk yield. Indeed, this technique of blowing into the vagina has been used as an aid to milking for centuries, and still is today.

The choreography of sex

For some species, the movement of a female's vaginal musculature takes on another significant task in sexual reproduction. For these females, controlling the direction of sperm transport is not enough; their muscles are also required to ensure sperm transfer occurs. That is, it is the female's forceful rhythmic muscle vibrations that are responsible for triggering ejaculation of semen. For example, the vaginal muscles of honey bees are

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

believed to be responsible for triggering the male's ejaculation, while the genital musculature of the marsh-dwelling bug is so strong that it effectively sucks sperm from the male's phallus. The idea that it is the contractile force of a female's vagina that provides the necessary physical stimulus for some males to ejaculate is lent weight by artificial insemination techniques. In male boars and dogs, for example, rhythmic pulsation (courtesy of a battery-powered vagina) must be applied to the penis if ejaculation is to occur.

This field of research - understanding how different species' vaginal muscles work during genital stimulation and/or orgasm - is still very much in its infancy, and much more research needs to be done before a clearer picture can emerge of how prevalent this 'ejaculation technique' is. Most of the studies are still confined to insect or mammal species. Yet, in the majority of species, a female's genital musculature is astonishingly steely, capable of providing the necessary phallic squeeze.

When it comes to primates, women are among those that show an ejaculatory muscular wherewithal. If a woman has well-developed vaginal muscles, it is possible, and pleasurable for her, to use them to grip, embrace, squeeze and ultimately cause herself to come, and the man to ejaculate. Movement on the male's part is not essential. It is also the case that the rapid forceful pelvic contractions that occur as a woman orgasms are often the physical (as well as erotic) extra that causes a man to orgasm and ejaculate. This timing - a woman's orgasm triggering a man's ejaculation - sits well with the theory of uterine and vaginal pressure changes and contractions influencing the upsuck of semen.

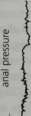

This idea of a female's orgasmic genital contractions providing the timely trigger for the male is underlined in intimate and surprising detail in a recording of the responses of two stumptail macaques during three consecutive copulations (see Figure 7.5). From the moment when the female presents to the male, to the point where she orgasms seven seconds before him during the first copulation, to the second and third copulations where they orgasm simultaneously, to the post-coital grooming session, an intriguing picture emerges of how synchronised the two stumptail macaques are in their sexual responses to each other. Not only do the climax faces coincide, but the point at which uterine activity increases rapidly and rhythmically in intensity immediately precedes the point of ejaculation each time. Interestingly, in the second and third copulation bouts, the female's 'look back and reach back' action appears to direct or signal the male's thrusting and ejaculatory response. Is she communicating to choreograph mutual orgasm?

In fact, there is a growing body of evidence showing that copulation in primates is characterised by an astonishing level of communication flowing between the female and male - be it facial (head-turning, looking

THE STORY OF V

O

2"

■b

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

di o

r o

OS <d

^OJ o

THE STORY OF V

back, climax face), vocal (copulation calls) or physical (reach and clutchback). This communication, it is suggested, plays a role in coordinating the male's thrusts and ejaculation with the female's muscular responses and orgasm. Moreover, it is the female who is the prime mover here. It is female rhesus monkeys that reach and clutch back, heralding their orgasm contractions, and seemingly firing off the male's ejaculatory response. Elsewhere, slow-motion films of bonobo sex reveal that the speed and intensity of the male's thrusting is regulated by the female's facial expressions, and/or her vocalisations. Bonobos also communicate sexual information physically. Amazingly, evidence shows that bonobos have developed their own sexual lexicon of hand gestures to negotiate and co-ordinate movements in sexual bouts.

While it is certainly true that today human female orgasm is not essential for conception to occur, I believe that the influence orgasm continues to have on egg extrusion and movement (ovulation and whether implantation occurs), as well as sperm transport and sperm transfer, points to the origin of this pleasurable muscle and nerve phenomenon. I imagine that female orgasm - the rhythmic, forceful, rippling contractions and relaxations of genital muscles - evolved from the female's need to control and co-ordinate the transport of both ova and sperm within her reproductive anatomy. With its accompanying symphony of hormones, the (orgasmic) muscular contractions of female genitalia do indeed manage to orchestrate egg and sperm movement, often with an exquisite amount of precision. Reproductively speaking, it is to every female's advantage to be able to achieve this manipulation of egg and sperm movement inside herself. The result, if a female is allowed free choice of mates and free movement of her genitalia, is conception with the most genetically compatible partner, and hence optimally successful sexual reproduction.

The penis as internal courtship device

This book has looked in large part at the raison d'etre of the vagina - in both sexual pleasure and reproduction. And one particular view explored is why it is essential for internally fertilising females to possess fully functioning, exquisitely sensitive and powerfully muscular genitals. However, this story would not be complete if some further consideration was not given to the penis - most males' vaginal equivalent. If the vagina's primary role is to ensure successful sexual reproduction with the most genetically compatible males, what is the purpose of the penis? Some might say that the penis functions purely as a sperm placement tool, a rigid insertion device shaped to shoot sperm quickly and efficiently into the correct orifice. However, a quick glance at different species' copulatory

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

routines and the time it takes males to ejaculate reveals that this cannot be the whole tale.

Sex sequences across the animal kingdom are routinely complex and lengthy. Some males spend hours stimulating females, genitally and otherwise, before they even present their phallus to her. Rubbing, caressing, kissing, stroking, vibrating, nuzzling, rocking, even singing and feeding, can form part of a male's essential copulatory courtship. And once genitally surrounded by the female, many other males take far more time than is necessary to give up their gametes if sperm deposition is the only goal of the routine. Spider monkeys stay mounted for up to thirty-five minutes, while sex for greater galagos can last more than two hours. The male marsupial mouse, Antechinus flavipes, must thrust inside the female about once every four minutes during the approximately five hours of copulation.

It's not just mammals that delay ejaculation; many other species do to. The male tsetse fly copulates on average for sixty-nine minutes, with sperm transfer only occurring in the last thirty seconds. Many spiders put the majority of their copulatory vigour into foreplay techniques. For example, the Sierra dome spider (Nereine litigiosa), will spend between two and six hours using its pedipalps (spider phallus) to stimulate the female genitally. Only after he has done this will he put sperm on the palps and attempt to inseminate her (this can take between 0.5 and 1.4 hours). Post-ejaculation, many species must continue to stimulate the female. Have a thought for the male thick-tailed bushbaby, where intromission (penis insertion) has to be heroically maintained for up to 260 minutes after ejaculation, although it appears that only intermittent bouts of thrusting are called for.

In fact, it is increasingly recognised that the answer to what the phallus is for lies in how a male's phallus can affect the vaginal environment that any sperm land in. As the majority of females enjoy multiple mating habits, the important question for a male is not: Can I place my sperm inside this female? Rather the crucial question is: Can I persuade this female to use my sperm instead of some other male's? Can I convince her, courtesy of the genital stimulation and pleasure my penis can provide, to take my sperm, transport it internally, and use it for fertilisation, rather than dumping it or destroying it? In fact, the primary role of the penis is none other than to act as an internal courtship device - shaped to provide the vagina with the best possible and reproductively successful stimulation. Providing the best, which in all likelihood means the most pleasurable genital stimulation, is, it seems, the way in which a male can persuade a female that he is fit to father some of her offspring.

This idea - that different species' penises are designed to provide maximum vaginal stimulation - is backed up by studies examining penis

THE STORY OF V

M. arctoides

Figure 7.6 Measuring up for optimal stimulation: how the shape of female and male genitalia compare in macaques. The shaded areas of the females' genitalia show the extent of the uterine cervix, uo indicates the urethral opening of the male primate's penis (adapted from Dixson AF, 1998).

shape and movement and how this corresponds to vaginal and cervical structures; and by research analysing how increasingly intricate penile designs are correlated with increasingly complex female mating habits. First of all, penis shape and movement, and how it complements female genitalia. The curious helical shape of a pig's penis, with its screw-tip ending, appears to fit beautifully with a sow's spiral-shaped cervix. And it seems that this end structure is important in persuading a female pig to retain more sperm. Artificial insemination studies have shown that semen flowback is reduced if an artificial penis with a similar helical tip is used. The tail-like filament at the end of a bull's phallus suggests a similar story. It flips forwards at the point of ejaculation, seemingly designed to do nothing other than stimulate the female. Figure 7.6 shows how the vaginas and cervices of three species of macaques correspond with the males' phalluses.

Whether it is the specifically mushroom-shaped glans; or the frills and lappets surrounding the penile tip; or the elaborate adornments, sculpted lumps, bumps, spines and denticles found on a phallus' surface - all these penile accoutrements are there, it seems, to give the male an additional way of stimulating the female vaginally, in the hope that this stimulation will persuade her to use his sperm rather than another male's. Intriguingly, analyses of how penile design correlates with female mating habits show

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

that the more complex and various a female's sexual behaviour, the more complex and elaborate a male's penis/internal courtship device is. To date, studies looking at bees, butterflies, beetles, primates and more have all borne out this theory. It appears that the sexual habits of the female determine and sculpt the structure of a male's phallus. That is, female sexual behaviour drives the evolution of the penis. And female genital structure and the pleasure it provides set the parameters for a species' sexual choreography.

The best pick-me-up of all?

There is an intriguing footnote to science's search to understand the significance of female genital pleasure and orgasm, and it explains why having an orgasm can cure a headache. Orgasm, you see, is a potent analgesic. That is, female orgasm increases a woman's threshold to pain (the point at which an externally applied increasing pressure becomes painful); in other words, orgasm has a pain-suppressing effect. Critically though, female orgasm does this without affecting a woman's response to tactile or pressure stimulation (it is not an anaesthetic and does not dull sensations). Startlingly, studies show that women's pain thresholds increase by over 100 per cent as a result of orgasmic vaginal and cervical stimulation.

Research has also revealed that it's not just orgasm that has this effect; vaginal stimulation does too. However, the degree of pain suppression depends on the pleasure experienced - pleasurable vaginocervical stimulation increased women's pain thresholds by 75 per cent. This pain-blocking effect of pleasurable and orgasmic vaginal stimulation is found in other species too, including rats and cats, and these studies have shown the potent analgesic effect to be mediated by two genitospinal nerves -the pelvic and hypogastric nerves. In female rats, the vaginal stimulation of mating produces potent analgesia equivalent to a more than 15 mg/kg dose of morphine sulfate.

Why should vaginal stimulation and orgasm be an analgesic? One answer may lie in the multiple mating habits that the majority of females enjoy. It's suggested that this pain-attenuating mechanism may ensure that repeated copulations do not aggravate, irritate or cause pain to a female's genitalia, which from a reproductive point of view need to be sensitive and highly responsive. Imagine if the intense sensory stimulation of sex commonly resulted in genital hypersensitivity. In this scenario, females and males might never get close enough to each other for long enough to reproduce successfully. Which would be disastrous for the survival of a species. In this sense, it is suggested that female sexual pleasure could be a significant adaptive factor in the physiology of reproduction and the evolution of the species.

THE STORY OF V

One of the most common ideas about female genitalia over the last few centuries has been that the vagina has no role to play in sexual pleasure and reproduction other than that of a passive sperm vessel. What this book has hopefully demonstrated is that this notion is incorrect. Female genitalia are highly sensitive and responsive because they have a very significant and powerful role to carry out in both sexual reproduction and pleasure - for both the female and the male.

The pleasure principle

I would like to finish this book with a comment on a person's capacity for genital pleasure and orgasm. Everyone begins their life with an infinite capacity to experience and enjoy pleasure. This is as true of genitally focused pleasure as it is of any other source. Foetuses orgasming in the womb underline this. Significantly, though, it is increasingly recognised that how an individual responds to sexual pleasure (or any kind of pleasure) during their life is a mixture of both the physical processes the body is undergoing, and a completely subjective perception of what those processes represent. That is, a person's perception of sexual pleasure can be as contingent on their past experiences of genital pleasure (or lack of pleasure), and the rules and values their society promotes, as it is on the sea of chemicals that arousal and orgasm send coursing through their bloodstream.

First of all, how experience influences the enjoyment of genital pleasure. A lifetime, or merely a childhood, of being told to ignore genital sensations, or, on the other hand, never having anyone in 'authority' explain that genital pleasure is to be valued, can and does have a blunting effect on how an individual responds to the build-up and release of genital/sexual sensations in their body. For some lucky individuals, these sensations are taught as ones to be valued and are therefore rated as pleasurable; for others, their previous experiences teach them to ignore or suppress these stimuli or label them negatively. How subjective the perception of pleasure can be is illustrated by people's responses to orgasm. Some descriptions of orgasm talk of the sensation as being frightening; others speak of it being the most exciting, fulfilling and enjoyable sensation imaginable. The flood of chemicals may be the same, but the emotional response to that rush differs depending on a person's history.

The brain is, in fact, an amazingly powerful sexual organ, perhaps the most powerful, and is supremely capable of overriding sexual signals, if a person's past has taught them that it may be 'safer' or 'better' to do so. Indeed, studies have shown that the physical effects of female arousal and orgasm can be 'overlooked' or ignored. And ignoring or suppressing

THE FUNCTION OF THE ORGASM

feelings of genital arousal is, it's suggested, easier for women to do, as they do not have an obvious visual sign of arousal to underline or emphasise how their body is actually feeling. Men, on the other hand, have in their erect penises a very handy feedback device, reminding them of how they feel, and making it a lot harder to 'ignore' genital sensations.

Secondly, society's role in valuing genital pleasure and orgasm. In the western world and the majority of societies, knowledge about genitalia and sexual pleasure has, until very recently, been shrouded under layers of religious and scientific ideology, much of it misleading or damaging. This is particularly true when it comes to discussions about female genitalia and female sexual pleasure. For these reasons, I don't find it particularly surprising that not all women enjoy their vaginas as much as they could. Anthropological evidence contrasting different cultures' attitudes towards information about sex and genital pleasure have revealed over and over again striking variations in orgasmic response. In societies where little or no sex education is given, and sex is decreed to be for procreation not pleasure, female orgasm and sexual pleasure can be relatively unknown. Yet, in those societies where women and men are taught from an early age to appreciate their own, and each other's, genitalia, as well as the pleasure genitals give, orgasm is achieved virtually universally and without difficulty for both sexes.

In 1948, the anthropologist Margaret Mead, after observing several Pacific Island societies, made some remarkably astute observations on the cultural factors that affect a woman's capacity to experience sexual pleasure and orgasms (they also apply to men). Mead wrote that in order for a female to find sexual fulfilment:

1. She must live in a culture that recognises female desire as being of value.

2. Her culture must allow her to understand the mechanics of her sexual anatomy.

3. Her culture must teach the various sexual skills that can make women experience orgasm.

Fortunately for women (and men) the three tenets of this vital sex education message are starting to come across in the west, albeit slowly. Unbiased information about female genitalia and their role in sexual pleasure and reproduction is increasingly available, and the vagina is beginning to be viewed as valuable, from both a scientific and a cultural perspective - just as mythology tells us it should be. Unlike the sixteenth-century St Teresa, women can, and do, rejoice in their genitals and the pleasure they bring, as the following twentieth-century description of female orgasm shows: 'Without any effort or trying on my part, my body was moved from within, so to speak, and everything was right. There was

THE STORY OF V

rhythmic movement and a feeling of ecstasy at being part of something much greater than myself and finally of reward, of real satisfaction and peace.' Pride, pleasure and the miracle of creation - this view of the vagina is the real story of V.

FURTHER READING

Chapter 1: The Origin of the World

Andersen, Jorgen, The Witch on the Wall: Medieval Erotic Sculpture in the British Isles, Copenhagen: Rosenkilde & Bagger, 1977.

Ardener, Shirley, A note on gender iconography: the vagina', The Cultural Construction of Sexuality, ed. Pat Caplan, London: Tavistock, 1987 113— 42.

Bishop, Clifford, Sex and Spirit, London: Macmillan Reference Books, 1996.

Camphausen, Rufus C, The Yoni: Sacred Symbol of Female Creative Power, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1996.

Camphausen, Rufus C, The Encyclopaedia of Sacred Sexuality: From Aphrodisiacs and Ecstasy to Yoni Worship and Zap-Lam Yoga, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 1999.

Clark, Kenneth, The Nude, London: Penguin Books, 1956.

Estes, Clarissa Pinkola, Women Who Run With the Wolves: Contacting the Power of the Wild Woman, London: Rider, 1992.

Frank, Anne, The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition, new translation, ed. Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler, London: Puffin, 1997.

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva, In the Wake of the Goddesses: Women, Culture and the Biblical Transformation of Pagan Myth, New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1992.

Gimbutas, Marija, The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe - Myths and Cult Images, London: Thames and Hudson, 1982.

Gimbutas, Marija, The Living Goddesses, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999.

Gimbutas, Marija, The Language of the Goddess, London: Thames and Hudson, 2001.

Halperin, David M., Winkler, John J., Zeitlin, Froma L, Before Sexuality, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Jochle, W., 'Biology and pathology of reproduction in Greek mythology', Contraception, 4 (1971), 1-13.

Lederer, Wolfgang, The Fear of Women, New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jov-anovich, 1968.

Lubell, Winifred Milius, The Metamorphosis of Baubo: Myths of Woman's Sexual Energy, Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1994.

THE STORY OF V

Marshack, A., 'The Female Image: A "Time-factored" Symbol. A Study in

Style and Aspects of Image Use in the Upper Palaeolithic', Proceedings of

the Prehistoric Society, 57 (1991), 17-31. Marshack, A., The Roots of Civilisation, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972. Murray, M. A., 'Female Fertility Figures', Journal of the Royal Anthropological

Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 64 (1934), 93-100. Neumann, Erich, The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype, trans.

Ralph Mannheim, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1963. Rudgeley, Richard, Lost Civilisations of the Stone Age, London: Arrow Books,

1999. Singer, Kurt, 'Cowrie and Baubo in Early Japan', Man, 40 (1940), 50-53. Stevens, John, The Cosmic Embrace: An Illustrated Guide to Sacred Sex,

London: Thames and Hudson, 1999. Stone, Merlin, When God Was a Woman, Florida: Harcourt Brace, 1976. Suggs, R. C, Marquesan Sexual Behaviour, New York: Harcourt & Brace,

1966. Taylor, Timothy, The Prehistory of Sex: Four Million Years of Human Sexual

Culture, London: Fourth Estate, 1997. Weir, Anthony, and Jerman, James, Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on

Medieval Churches, London: Routledge, 1986. Yalom, Marilyn, A History of the Breast, London: Pandora, 1998.

Chapter 2: Femalia

Adams, J. N., The Latin Sexual Vocabulary, London: Duckworth, 1982.

Blank, Joani, Femalia, San Francisco: Down There Press, 1993.

Burgen, Stephen, Your Mother's Tongue: A Book of European Invective,

London: Gollancz, 1996. Chia, Mantak, and Chia, Maneewan, Cultivating Female Sexual Energy:

Healing Love Through the Tao, New York: Healing Tao Books, 1986. de Graaf, Reinier, 'New Treatise Concerning the Generative Organs of

Women', 1672, annotated translation by Jocelyn, H B., and Setchell, B.P.,

Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, Supplement 17, Oxford: Blackwell

Scientific Publications, 1972. Dickinson, Robert Latou, Human Sex Anatomy, Baltimore: Williams &

Wilkins, 1949. Dreger, Alice Domurat, Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex,

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998. Eisler, Riane, The Chalice and the Blade, California: HarperCollins, 1988. Ensler, Eve, The Vagina Monologues, New York: Villard, 1998. Fagan, Brian, From Black Land to Fifth Sun: The Science of Sacred Sites,

Reading, Mass.: Perseus Books, 1998. Fissell, Mary, 'Gender and Generation: Representing Reproduction in Early

Modern England', Gender and History, 7 (3) (1995), 433-56.

300

FURTHER READING

Laqueur, Thomas, Making Sex: Body and Gender From the Greeks to Freud, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Lemay, Helen Rodnite, Women s Secrets: A Translation of Pseudo-Albertus Magnus' De Secretis Mulierum with Commentaries, New York: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Paros, Lawrence, The Erotic Tongue: A Sexual Lexicon, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1984.

Porter, Roy, and Hall, Lesley, The Facts of Life: The Creation of Sexual Knowledge in Britain, 1650-1950, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995.

Schiebinger, Londa, The Mind Has No Sex? Women in the Origins of Modern Science, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Tannahill, Reay, Sex in History, London: Abacus, 1989.

Chapter 3: A Velvet Revolution

Arthur Jr, Benjamin I., Hauschteck-Jungen, Elisabeth, Nothiger, Rolf, Ward,

Paul I., 'A female nervous system is necessary for normal sperm storage

in Drosophila melanogaster. a masculinized system is as good as none',

Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 265 (1998), 1749-53. Ben-Ari, Elia T., 'Choosy Females', BioScience, 50 (2000), 7-12. Birkhead, T.R., and Moller, A. P., (eds.), Sperm Competition and Sexual

Selection, London: Academic Press, 1998. Birkhead, Tim, Promiscuity: An Evolutionary History of Sperm Competition

and Sexual Conflict, London: Faber and Faber, 2000. Calsbeek, Ryan, and Sinervo, Bary, 'Uncoupling direct and indirect components of female choice in the wild', Proceedings of the National Academy

of Sciences, 99 (23) (2000), 14897-902. Eberhard, William C, Sexual Selection and Animal Genitalia, Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985. Eberhard, William G., Female Control: Sexual Selection by Cryptic Female

Choice, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996. Frank, L.G., Glickman, S.E., Powch, I., 'Sexual dimorphism in the spotted

hyaena (Crocuta crocuta)\ Journal of Zoology, 221 (1990), 308-13. Frank, Laurence G., 'Evolution of genital masculinization: why do female

hyaenas have such a large "penis"?', Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 12

(1997), 58-62. Hellrigel, Barbara, and Bernasconi, Giorgina, 'Female-mediated differential

sperm storage in a fly with complex spermathecae, Scatophaga stercoraria,

Animal Behaviour, 59 (1999), 311-17. Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer, The Woman That Never Evolved, Cambridge, Mass.:

Harvard University Press, 1999. Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer, Mother Nature: Natural Selection & the Female of the

Species, London: Chatto & Windus, 1999.

THE STORY OF V

Margulis, Lynn, and Sagan, Dorion, What is Sex?, New York: Simon &

Schuster Editions, 1997. Neubaum, Deborah M., and Wolfner, Mariana R, 'Wise, winsome or weird?

Mechanisms of sperm storage in female animals', Current Topics in Developmental Biology, 41 (1999), 67-97.. Newcomer, Scott, Zeh, David, Zeh, Jeanne, 'Genetic benefits enhance the

reproductive success of polyandrous females', Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, 96 (102) (1999), 36-41. Pitnick, Scott, Markow, Therese, Spicer, Greg S., 'Evolution of multiple

kinds of female sperm-storage organs in Drosophila\ Evolution, 53 (6)

(1999), 1804-22. Pizzari, T., and Birkhead, T. R., 'Female feral fowl eject sperm of sub-

dominant males', Nature, 405 (2000), 787-9. Small, Meredith R, Female Choices: Sexual Behaviour of Female Primates,

Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993. Tavris, Carol, The Mismeasure of Woman, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. Wedekind, Claus, Chapuisat, M., Macas, E., Rulicke, T., 'Non-random

fertilization in mice correlates with MHC and something else', Heredity,

77 (1995), 400-9.

Chapter 4: Eve's Secrets

Angier, Natalie, Woman: An Intimate Geography, London: Virago, 1999. Bagemihl, Bruce, Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural

Diversity, London: Profile Books, 1999. Chalker, Rebecca, The Clitoral Truth, New York: Seven Stories Press, 2000. Cloudsley, Anne, Women ofOmdurman: life, Love and the Cult of Virginity,

London: Ethnographica, 1983. de Waal, Frans, and Lanting, Frans, Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1997. Dixson, Alan R, Primate Sexuality: Comparative studies of the prosimians,

monkeys, apes and human beings, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. Fisher, Helen, Anatomy of Love: A Natural History of Mating, Marriage and

Why We Stray, New York: Ballantine Books, 1992. Galen, On the Usefulness of the Parts (De usu partinum), Book 14.9, Vol. II,

trans. Margaret Tallmadge May, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University

Press, 1968. Lowndes Sevely, Josephine, Eve's Secrets: A New Theory of Female Sexuality,

New York: Random House, 1987. Lowry, Thomas Power (ed.) The Classic Clitoris: Historic Contributions to

Scientific Sexuality, Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1978. Moore, Lisa Jean, and Clarke, Adele E., 'Clitoral Conventions and Transgressions: Graphic Representations in Anatomy Texts, c. 1900-1991',

Feminist Studies, 21 (1995), 255-301.

FURTHER READING

Moscucci, Ornella, The Science of Woman: Gynaecology and Gender in England 1800-1929, Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1990.

O'Connell, Helen, Hutson, John, Anderson, Colin, Plenter, Robert, 'Anatomical relationship between urethra and clitoris', The Journal of Urology, 159(1998), 1892-7.

Pinto-Correia, Clara, The Ovary of Eve: Egg and Sperm and Preformation, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Schiebinger, Londa, Nature's Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science, Boston: Beacon Press, 1993.

Sissa, Giulia, Greek Virginity, trans. Arthur Goldhammer, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Chapter 5: Opening Pandoras Box

Austin, C.R., 'Sperm fertility, viability and persistence in the female tract', Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, Supplement 22 (1975), 75-89.

Cabello Santamaria R, and Nesters R., 'Retrograde ejaculation: a new theory of female ejaculation', paper given at the 13th Congress of Sexology, Barcelona, Spain, August 1997.

Carr, Pat, and Gingerich, Willard, 'The Vagina Dentata Motif in Nahuatl and Pueblo Mythic. Narratives: A Comparative Study', Smoothing the Ground, Essays on Native American Oral Literature, ed. Brian Swann, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983.

Douglas, Nik, and Slinger, Penny, Sexual Secrets: The Alchemy of Ecstasy, Vermont: Destiny Books, 1979.

Douglass, Marcia, and Douglass, Lisa, Are We Having Fun Yet?: The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Sex, New York: Hyperion, 1997.

Faix, A., Lapray, J.F., Courtieu, C, Maubon, A., Lanfrey, Kerry, 'Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Sexual Intercourse: Initial Experience', Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 27 (2001), 475-82.

Graber, Benjamin (ed.), Circumvaginal Musculature and Sexual Function, New York: S. Karger, 1982.

Grafenberg, Ernest, 'The Role of the Urethra in Female Orgasm', The International Journal of Sexology, Vol. Ill (3) (1950), 145-8.

Gregor, Thomas, Anxious Pleasures: The Sexual Lives of an Amazonian People, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Huffman, J.W., 'The Detailed Anatomy of the Paraurethral Ducts in the Adult Human Female', American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 55 (1948), 86-101.

Ladas, Alice Kahn, Whipple, Beverly, Perry, John D., The G Spot and Other Discoveries about Human Sexuality, New York: Bantam Doubleday, 1982.

Morgan, Elaine, The Descent of Woman: The Classic Study of Evolution, London: Souvenir Press, 1985.

Overstreet, J. W., and Mahi-Brown, C. A., 'Sperm Processing in the Female

THE STORY OF V

Reproductive Tract', ,Local Immunity in Reproduction Tract Tissues, ed.

RD. Griffin and P.M. Johnson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Perry, J.D., and Whipple, B., 'Pelvic muscle strength of female ejaculators:

Evidence in support of a new theory of orgasm', Journal of Sex Research,

17 (1981), 22-39. Raitt, Jill, 'The Vagina Dentata and the Immaculatus Uterus Divini Fontis,

The Journal of the American Academy of Religion, XLVIII/3 (1980), 415-

31. Ruan, Fang Fu, Sex in China: Studies in Sexology in Chinese Culture, New

York: Plenum Press, 1991. Schleiner, Winfried, Medical Ethics in the Renaissance, Washington, D.C.:

Georgetown University Press, 1995. Stuart, Elizabeth, and Spencer, Paula, The VBook: vital facts about the vulva,

vestibule, vagina and more, London: Piatkus, 2002. Sundahl, Deborah, Female Ejaculation & the G spot, Alameda, California: