3

Beyond Lassie

What is it with the fetish for romanticizing dogs? Dogs do not require such vain attempts at makeover. Their very nature possesses its own dignity, transcending any need of supplement and change. All that is required is our respect and admiration.

—Bless the Dogs

In World War I, on the war-ravaged French countryside, an American soldier named Lee Duncan stumbled upon what he believed was a miracle. A dog kennel had been nearly destroyed by an aerial bomb. Inside the wreckage lay the bodies of a dozen or so German shepherds. Then Duncan, who had grown up as an orphan, saw a mother shepherd nursing five puppies. Only days old, the pups hadn’t even opened their eyes. The young soldier took two of the whelps, a male and a female, all he could carry. His fellow soldiers rescued the mother and the other babies. Though Duncan’s female puppy would die of pneumonia, the male puppy, along with his soldier-master, would survive the war and then make their way to Duncan’s home in California.

The rescue of the shepherd puppy on the French countryside was only the beginning of the story. Duncan named the puppy Rin Tin Tin after a popular French doll. So bright was the fame of the war-born German shepherd that legend has it he received the most votes for Best Actor at the first Academy Awards in 1929. News of his death in 1932 interrupted radio broadcasts across the country.

Though Rin Tin Tin’s considerable talent as a performer made him a phenomenon and sold movie tickets by the millions, it was the tale of his relationship with Lee Duncan that transcended fictional entertainment and ultimately earned him a place in the hearts of the American people.

For many baby boomers and their children, film and television dogs like Rin Tin Tin, Lassie, and Benji set the standard for our expectations: a dog that was a loyal companion and that not only could take care of itself but also would rescue us in times of danger. “What is it, Lassie? Timmy fell down the well again?” Dogs are capable of amazing feats of valor, as evidenced by the canine parachute jumpers our US Army Special Forces employ or the search-and-rescue dogs we see working in times of natural or man-made disasters. But not even Rin Tin Tin or Lassie performed in real life as Hollywood depicted them. While Rin Tin Tin fed the imaginations of moviegoers, he also had episodes in real life where he snapped and barked at dog show judges, could be difficult and unruly, bit a number of actors and costars, and required hours of rigorous training each day with Lee. None of that was part of the image Hollywood wanted to project. Similarly, no one ever saw six-month-old Lassie being corrected for chewing the couch leg, or the arduous training it took to get him to stop on a mark. (Yes, Lassie was played by a succession of male collies.) Hollywood has never been about reality and so isn’t concerned with what happens behind the curtain during production. Only the final version on-screen is important. So, of course, all movie and TV dogs seem to behave perfectly. It didn’t matter if it took fourteen takes and a few bandages to get Rin Tin Tin’s scene shot as long as it looked perfect to the audience.

That said, if you are of a certain age, you most likely remember the dogs of your childhood as being very much part of your life, fitting seamlessly into your day-to-day activities. These companions of yesteryear didn’t seem to need obedience classes, scientific studies, or formal training. At least that’s the way we remember it. Owners didn’t have to be told to spend more time with their dogs or to give them special activities. We enjoyed a more natural, organic way of interacting and socializing; people tended to socialize with their dogs despite themselves. In many neighborhoods there were no leash laws. Our dogs ran out the front door with us on summer mornings, or waited for the school bus to drop us off on winter afternoons. Dogs were part of the pack of our gang—think The Little Rascals or Scooby-Doo—part of our family and our neighborhood. It was an environment that naturally programmed the dogs into our lives.

Dogs learned to behave simply by osmosis, or at least that is how we remember things.

That is an important caveat: or at least that is how we remember things. While there did seem to be a more natural and integral way of living with dogs in times past, some of our memories of the “good old days” are gilded. Aside from the fact that there were far fewer dogs in the first half of the twentieth century, the percentage of bad behavior among both dogs and dog owners was just as high then, maybe even higher than it is today. Our nostalgia conveniently leaves out some of the more unpleasant realities. Cars ran over unleashed dogs, visits to the vet happened only when something drastic went wrong, and many owners didn’t give dogs’ nutritional needs a second thought. From today’s perspective, such circumstances would constitute owner negligence. So it’s fair to say that a certain editing of our memories undoubtedly has taken place, a sanitizing of the stories that accentuates the good elements and minimizes the bad. Put into the blender, our memories create their own romanticism. But that shouldn’t obscure an important point: On some fundamental level, we did understand the true nature of our dogs better then, and it is vital to try to recover some wisdom from the past.

This is all the more imperative because times have changed. The boomers have aged and now carry into retirement a litany of pressing concerns and time constraints. Millennials are busy building careers in a competitive environment. Our litigious society has all but banned dogs from the myriad public places where they were once welcomed. So where is the dog in all of this?

A vast new breed of dog owner with less time than ever on his hands has evolved. Today, digital preoccupation holds us hostage. Children and teens sit for hours in front of digital devices playing video games. Even adults spend more time on Facebook and texting than talking face-to-face. We now rely on a world of digital connectedness. People walk down the street using a mobile phone for email, texting, and social media, staying connected with everything but their surroundings. More than one million car accidents a year involve texting. It’s not unusual for a group of friends to sit together at a restaurant all using social media rather than looking one another in the eye. The friends sitting together even text each other! People walk their dog (if the dog is lucky) while staring at a rectangle of plastic and black glass. Too many dogs are now either marginalized or, maybe worse, anthropomorphized. Instead of taking dogs along on trips, people board them in kennels or with dog sitters. Dogs spend more time with professional dog walkers or in doggy day care—or, worse yet, alone—than they do with their owners. When dogs are with their owners, they are treated not as pets but as human companions or therapy sponges to soak up their owners’ emotional needs.

The paradox here is that with all the supposed advances civilization has made over the past several decades, people are either distancing themselves from their dogs or making them into something they’re not. Our society has created a new romanticism, a new alienation from the dog’s true nature, that assumes that the dog can take care of itself and spend the bulk of its time alone. Or that the dog is a miniature human being with the same view of reality and needs as humans, as though the only important part of the equation is love. Too often we’re blind to the fact that what’s really needed is simple canine-human companionship and not some dressed-up version of that relationship. People have lost the natural wisdom that helped keep dogs well behaved and happy and our lives balanced. Because dogs live smack-dab in the here-and-now, where every smell, every sound, every sight deserves and receives their attention, they can help us reconnect to a world that often escapes our notice. Through their example, dogs remind us to engage, to go for a walk, to joyously roll and romp or even to enjoy a quietly shared moment; dogs guide us to become more human. They do this because dogs connect to the world not through their data plan but through the richness of their senses. When we listen to their message we are able to pay greater attention to the reality of now, to ourselves, even if initially it’s just for a few hours a day. The good news is that a simple walk with your dog (and with your cell phone put away) can go a long way toward reconnecting you both to this wondrous, real world. We can recover some of the best elements of that earlier era of dog companionship by honoring the spirit that the dog has always possessed and letting it blossom in our company. When we begin to give dogs what they need rather than what we need, we will have started the journey on the right foot.

But this leaves nagging questions that are brought up to us repeatedly: How do we get beyond the romanticism; how do we transform ideals into reality to attain this spiritual connection with our own dogs? What do dogs need? And how do we give it to them? There’s no shame in admitting that the devil is in the details (and we will address this throughout the book). But, before all else, let’s take a general overview of how a good relationship evolves and how you can integrate a dog into your life in a way that suits you both.

Just about every relationship between an owner and his dog starts with a dream. It doesn’t matter whether you’re purchasing your first puppy from a breeder or adopting your second or third full-grown dog from an animal shelter. Owners envision a dog that will be an important part of their lives, that will fit into their home and become a reliant companion filled with unconditional love. Emotionally, the dream is the same for practically everyone, but it needs to be translated into how a dog truly is, rather than the fantasy version of who we want him to be. We simply cannot overstate this: A relationship that is transformative for both you and your dog builds on an essential foundation of shared time, regular exercise, positive socialization, and dedication on your part to provide the dog with the basic essentials of what it needs. Leadership starts there. All dogs need this from us. With those elements in place, the dream can begin to take flight. The very happiness you will see in your dog each day—walking, hanging out with you, or playing a game of fetch after work—will only encourage you to take things even further. How much richer both of you will be! So root your dream in reality and watch how the process teaches you to live for an hour now and again without Internet.

BROTHER CHRISTOPHER Our own dream began when we experienced firsthand the importance of our first German shepherd, Kyr, in the early years of New Skete. Kyr was a mascot and best friend during the founding of New Skete, and his “joie de vivre,” good nature, and enthusiasm were stabilizing influences for all the monks during those stressful first years. It was only when Kyr passed away that everyone could see what a blessing he had been for us, how he actually inspired us. We never set out to breed German shepherds or train dogs, but the loss of Kyr made such a deep impression on us that we simply had to replace him with another shepherd. That led us to obtain two breeding-quality females, and things developed naturally from there: the idea of each monk caring for a dog, starting a breeding program of German shepherds, training dogs who could live harmoniously with their owners. This has been a grace that none of us could have anticipated. But here we are fifty years later. The strength of the approach we’ve developed in that time rests in the fact that it’s the product of the actual experience we’ve had of living with dogs—many, many dogs. Without rehashing what we’ve spoken about in our other books, this experience has taught us that romantic ideas about dogs that are filled with human projection may sell tickets for Hollywood studios and delight and entertain moviegoers, but they fail to offer a realistic portrayal of how we can live with our dogs and allow both species to flourish. Real life is where that occurs. When we think of the early days of New Skete, the primary lesson that jumps out is that the dogs were our best teachers. We listened to what their real needs were and worked energetically to help them live harmoniously with us and with one another. That meant providing effective leadership. Practically speaking, when you have a large group of powerful dogs living under the same roof with a group of ten to fifteen monks, you learn pretty quickly how to manage the dogs as they are, and not as you’d like them to be.

For example, we learned early on how important it is to respect biology. While we might like to have all the dogs be able to play and interact with one another, we discovered quickly that this isn’t always possible. In a breeding colony, you have to be very careful with the males you are using as studs. Inevitably they look at one another as competitors, and even if they’ve been raised together and got along as young dogs, how that changes once they begin to be used consistently for breeding! I will never forget the first dogfight I witnessed between two of our breeding male shepherds. It happened when one was accidentally let into a room where the other was resting. The fight progressed so quickly and so primally. It was only the quick work of two monks that enabled the two dogs to be separated without anyone getting seriously hurt. But we all understood immediately that we had dodged a bullet there. None of us had ever witnessed anything quite like that before—and it gave us a new respect for the dogs’ version of reality as canines.

Though we heartily encourage you to begin your relationship with your dog dreaming of good things to come, we also believe that a healthy, modern relationship between owner and dog begins with a thoughtful understanding of dogs and their behavior, an adherence to the natural order, and a deeply held love for the dog. This is what gets beyond romanticism and sentimentality. In real life, it takes more than the Hollywood version of love to sustain a healthy relationship between you and your dog. Understanding each other is what keeps the love affair going strong.

This requires a certain amount of work and study. If a foundation of knowledge is paramount to a happy relationship with your dog, let’s begin with a very brief overview of how dog training evolved. Today we are flooded with information about all sorts of dog-training philosophies. We find some more productive than others. But traced back to its beginnings, at least in its modern derivation, dog training draws inspiration from two basic theories of animal behavioral science.

One is the theory of behaviorism, which is the study of how animals learn. The psychologist B. F. Skinner is perhaps the most famous proponent of behaviorism. Skinner theorized that animals learn by experience and through responding to external stimuli. He believed that good behavior is strengthened when it’s reinforced, and bad behavior diminishes as it’s punished. He invented, as you might remember from your Intro to Psychology course, the Skinner box, in which, typically, a pigeon or rat was placed. The box included a lever, a slot for food, and water. If the pigeon or rat touched the lever, a pellet of food would come out of the slot. Skinner devised the experiments and recorded the results. What he learned was that he could “shape” the animals’ actions by rewarding certain behavior—like hitting the lever. There is no question that the general elements of behavior learning theory can be very helpful in the training process. However, we believe Skinner’s form of behaviorism was myopic, and when applied rigidly to a relationship with a dog it risks turning the dog into something that it is not: a behavioral machine. Skinner rejected the view that thoughts, feelings, and emotions are involved in causing behavior. But anyone who has ever lived with a dog would be hard-pressed to deny that dogs have emotions and feelings—feelings that are certainly more complex than those we’d ascribe to pigeons. Something of the dog gets lost in a purely Skinner view of animal behavior.

The other school of thought is ethology, the study of animals in their natural environment. Konrad Lorenz is probably the best-known figure in this field. The recipient of the 1973 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, Lorenz believed that nearly all animal behavior is innate. He posited that nature and genetics are responsible for the actions of your dog, and he can be interpreted (we believe unfairly) as downplaying the role of training in the life of the dog. Admittedly, much dog training today is based largely on Skinner’s theories, and this despite the fact that Skinner was a lab scientist, much more clinical than Lorenz, and, to our knowledge, never trained dogs. By contrast, Lorenz bred, trained, and lived with dogs his whole life. He also wrote extensively about them, including his iconic book Man Meets Dog, which we heartily recommend to all dog owners and prospective dog owners. You will, we promise, especially enjoy spending a summer’s day with Lorenz and his beloved Susi in his essay (with charming sketches) entitled “Dog Days.” Lorenz didn’t embrace the romantic ideal of the dog; rather, his inspiration was the reality of the relationships he had with his dogs.

We realize, of course, that many dog owners today don’t have the luxury of time that Lorenz may have had. We also know that not all of Lorenz’s teaching methods have stood the test of time. But his explanation of the relationship among man, dog, and nature, like a good wine or a classic novel, goes to the very heart of the lesson we are trying to impart in this book.

We believe that the same loving and intentional interaction that Lorenz describes can—and should—exist in the time you do spend with your dog in today’s busy world. We also believe the payoff is extraordinary, but it needs to be grounded in reality. Uncritically accepting statements like “Dogs have an innate desire to please” is not helpful and doesn’t honor the real nature of the dog. If dogs had a simplistic innate desire to please, then why does your dog have any bad habits at all? Your dog would just always obey and comply out of its desire to please. No, quite understandably, dogs have an innate desire to please themselves, just as we do. However, as we help dogs discover the benefits of cooperating with a conscientious and loving human being, the true nobility of the dog is revealed. That is what we want to draw out. Indeed, the “unconditional” love of the dog is most manifest when the dog is raised in an atmosphere of responsibility, leadership, and companionship. In this context, dogs nurture our sense of self-worth by making us the center of their universe. From them, we learn a dignity that comes from within, not out of some external circumstance. Dogs tell us what’s important in life: They don’t care what we look like, whether or not our hair is done, or if we’re clean-shaven. It doesn’t matter to a dog what you do for a living, or how much money you have in the bank. From dogs we learn how to connect in spiritual ways with the beauty of the world that surrounds us. In return, all dogs ask for is a walk with some basic rules, a kind word, and a warm bed in the heart of our home… in short, to be included in our lives.

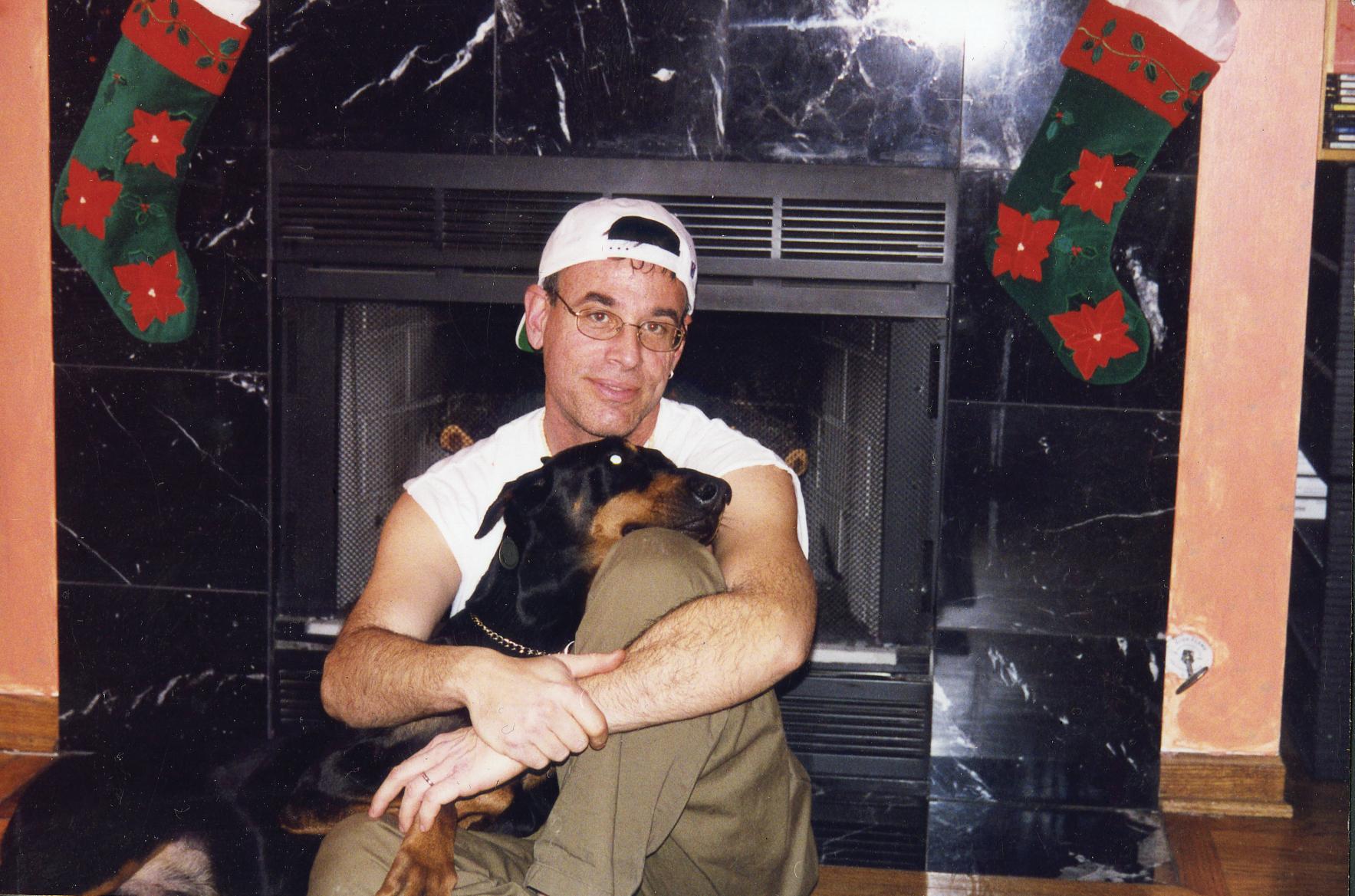

When a dog learns to cooperate with a human being, his unconditionally loving nature comes through. Here you can see the devotion between Marc Goldberg and Diablo.

But how? you ask. Well, in addition to establishing a consistent schedule for feeding, walking, playing, and just being with your dog, there is so much more that you can do. If there is love and a willingness to understand your dog’s true nature, then there is fertile soil in which a healthy relationship can grow. In a world where humans seem to become more detached and isolated with every technological advancement, dogs remind us of the profound spiritual connection we have with animals and to the good Earth. There are abundant opportunities to prime the relationship and take it beyond sentimental stereotypes—and to become more human in the process.

One obvious way to spend more time with your dog is to include her in your everyday routine. Long walks and exercise in dog-friendly parks are a natural opportunity to build on your relationship with your pet while at the same time offering a reprieve from the daily rat race. Dog owners with families should share the responsibility and the fun. Let everyone spend quality time with the family dog or dogs, either separately, together, or both.

This is eminently doable these days. Taking advantage of the dog-friendly aspects and amenities of the town or city you live in is a great way to share your life with your dog. Chicago offers several dog-friendly beaches and at least eighteen off-leash parks. Las Vegas is also very dog-friendly, with at least twenty-five off-leash parks. Orlando, Seattle, and Austin, Texas, all have made “best dog-friendly cities” lists. In New York City, the great and expansive Central Park is all yours and your dog’s with an off-leash allowance, albeit before 9:00 a.m. or after 9:00 p.m. Many city dog owners spend a good amount of time in the park before they head off to work.

Dog owners in big cities more often integrate dogs into their lives as a matter of course. They’re used to sharing limited apartment space and having a communal experience. City dogs learn how to follow their owners’ lead out of necessity. They must become accustomed to loud noises, cramped elevators, and navigating city traffic, whether vehicular or pedestrian. Both owner and dog must be alert on even the most casual walk. The city experience intensifies the dog and owner bond.

Like graffiti artists, city dogs and their owners use the urban landscape as a canvas, finding ways to artfully coexist. We know of one New York City resident who awakes before dawn and, with his dog, makes his way to a park along the East River. There, dog and owner watch the sun rise each morning over the borough of Queens.

But big-city dwellers don’t have a monopoly on the art of living with their dogs. Real rural living, with its wide-open spaces, dense woods, minimal traffic, and nature in all her abundance and splendor, is wonderful for building a happy relationship with your dog—that is, if you don’t use the idyllic setting as an excuse to shirk your responsibilities. We monks know a bit about rural living—our monastery sits on top of a mountain. For example, we know plenty of local hunters who take their dogs into the woods regularly for exercise and work, in season and out, and a number of farmers whose dogs accompany them on their daily chores. These are well-adjusted, happy dogs that spend a lot of time with their owners. On the flip side, there is sometimes a temptation in rural locales to let dogs fend too much for themselves. Far too often we’ve heard stories from the locals about dogs being hit by cars or hurt in other accidents because they were without supervision.

BROTHER CHRISTOPHER A common rural mentality is that the dog can take care of itself—after all, there’s an abundance of open space to occupy the dog’s time and attention. The dog can make hay with its freedom and will not place any inconvenient demands on the owner’s time and attention. The only problem with this attitude is that it plays Russian roulette with the dog’s life. I remember a number of years back, for example, a cute mixed-breed puppy that was set out free in its front yard every day. If it wasn’t in its yard it was walking along the road, able to explore the local woods or romp in the creek. To some people’s eye, it was absolutely idyllic. The dog was totally free. I remember the intense sadness I felt one day when I drove past its property and there was the dog on the side of the road, a lifeless corpse that had been hit by a car.

Still, there is nothing as natural as a country or farm dog, and life with such a dog can occupy the very pinnacle of human-dog relationships.

Suburbs, too, provide many opportunities to integrate your life with your dog’s. With a profusion of lawns and parks, and with significant dog populations, there are ample possibilities for exercise, play with children, and safe interaction with other dogs. Responsible doggy day care facilities are springing up in such locales to give owners who work greater flexibility in meeting their dogs’ social needs. That said, lax leash laws and heavily trafficked roads can become, without proper training, a dangerous environment for your dog. So be vigilant and realistic about what your dog’s capabilities are.

Regardless of where you live—city, suburbs, or country—there are plenty of ways for your dog to spend quality time with you. Years ago, we didn’t think twice about loading the dog in the family station wagon. Today it takes a little more thought, planning, and training, but taking your dog along in the car with you can build a sense of camaraderie, a feeling of being together in this adventure called everyday life. We’re surprised at the number of dogs that get in the car so infrequently that they see even a short trip as a terrifying or (literally) nauseating ordeal, or that spend the whole ride jumping from back to front, barking at everything they see.

A dog that is comfortable in the car can go more places with you…but don’t let him drive.

We recall one client who brought her Labrador for training, and when she opened the rear door there were three piles of vomit and bile on the upholstery. This was the reason the woman never took the dog with her in the car. Apparently, the dog would vomit during every trip. Our training of the Lab included helping her associate riding in the car with something she really liked: playing with a favorite toy, for instance. After the ride, we would spend ten minutes playing fetch with her squeaky toy. It was amazing how quickly the dog’s attitude changed and her nausea vanished, and how quickly the relationship between the dog and her owner began to improve as a result.

We recommend that you start by taking your dog on short trips, just down the block and back. You might also want to refrain from feeding or giving him water for a few hours beforehand. First, lower the window just a bit so your dog may enjoy the breeze in his snout. Windows should never be left fully open, however. Although it might look cute to see a pooch’s head hanging out the window of a car, tongue a red ribbon flapping in the breeze, it’s never a safe practice for any animal (or person) to hang out of a moving car. An open window might also prove too tempting of an escape route for some adventurous breeds, and a bug or pebble hitting an eye at sixty miles per hour can do serious damage. Make sure your dog is completely at ease in the vehicle before you attempt any long trips or travel on crowded highways. A canine safety harness, a partition, or a crate are all good options for keeping your dog safe in a moving car. A dog that is easily excited can be a dangerous distraction to a driver. A calm and comfortable dog, however, is a wonderful road-trip companion.

Family vacations to pet-friendly destinations, or just to the seashore or mountains, will go a long way toward integrating your pet into the family. RV parks and campgrounds across the country are investing in dog-friendly features, including leash-free areas and agility courses, according to the New York Times.* In our own travels overseas, we have been heartened to see what is recounted so lovingly in Lorenz’s book—the integration of dogs into everyday village life. Paris is as famous for its dog-friendliness as it is for its fashion and food. In a park outside the Louvre, with the Eiffel Tower in the background, Parisians meet to let their dogs play and interact. You see dogs on the Metro and sitting at outdoor cafés with their owners. More than the dog-friendly amenities, Paris offers an example of how an intentional relationship with your dog can enhance even the most cosmopolitan existence. For Parisians, a dog adds to the enjoyment of a simple walk, like crusty bread with your soup or chocolate with your coffee. Even chilly old England warms when it comes to its dogs, as the stories of James Herriot and Queen Elizabeth’s well-known love for her corgis pointedly attest.

We notice one other important cultural difference between Americans and Europeans. Americans tend to infantilize their dogs. They baby talk to them, they touch them constantly, and they buy them tons of toys. At the same time, Americans leave their dogs alone a lot. Perhaps a sense of guilt for leaving the dogs contributes to Americans spoiling their dogs on occasion. Americans even spoil other people’s dogs, stopping them on the street to talk to the dogs as though they were public property. Europeans, by contrast, take their dogs everywhere. Yet if you were to address—or, worse yet, touch—a stranger’s dog on the street in Europe, you’d quickly get an earful. It simply isn’t done. And, as a result, the European dogs are calmly integrated into public life, able to spend much more time with their owners than most American dogs manage.

MARC I was in a pub in the Elephant and Castle section of London, and there was a Doberman bitch lounging on the floor of the bar. The barman, who happened to own the pub, noticed my appreciation of the dog’s beauty. “You want to see the pups?” he asked in a Cockney accent. He then disappeared through a door behind the bar and reemerged with his arms filled with eight-week-old Doberman pups. I was soon engulfed in a cuddle puddle of puppies. As I walked from the pub that day, I realized that the pub owner had accomplished something truly beautiful: He had seamlessly integrated his dogs into his life. For the price of a pint, a patron would experience his pub, his family, and his dogs all in one visit. It was wonderful.

Zombies, Run!

Another terrific way to make your dog part of your life is to have her join you in your fitness routine. Today, all sorts of running apps fill the market, including one that challenges you to outrun the walking dead. Having a real, living dog along on your run can be equally exciting. A dog makes for a very enthusiastic training companion. Here too, however, dogs need to be indoctrinated into the routine. Start with a long lead and a brisk walking pace. As your dog gets used to the freedom of the run, increase your speed and shorten the lead. Many dogs have a talent for pace and a real runner’s determination. It’s important to remember, though, that dogs get hot more quickly than you do, and you should bring a water bottle for them and teach them how to drink from it. Though not all dogs are cut out for long distances, many can be perfect running partners: Labs, boxers, and English setters, for instance. Dogs can also enjoy roadwork by accompanying owners on bicycles and even roller skates, though this calls for a high degree of skill and discipline. You don’t want to be a novice on Rollerblades with Rover in hot pursuit of a squirrel or another dog. For bicyclists, use a springer attachment to keep your dog at a safe distance from the wheels. Whenever you’re on the go, consider bringing your buddy. Playing Frisbee, swimming, hiking, running on a dog-friendly beach—all not only are invigorating but also go a long way toward building a healthy connection between your dog and you.

Perhaps you’re lucky enough to be employed by someone who lets you bring your dog to work. Google, Amazon, Ben & Jerry’s, and Procter & Gamble are a few of the bigger dog-friendly firms, but there are plenty of small companies that allow—even encourage—canine companionship at work. Some of us work for ourselves. Others work from home. Whatever the situation, if you can bring your dog with you to your workplace, please do. It will provide a natural opportunity to strengthen the bond you share with your dog by significantly increasing her presence in your life each day.

We know from experience dogs aren’t all that fond of barriers, especially the ones that keep them apart from their owners. There is nothing as forlorn as the bark of a lonely dog from behind a fence. Sometimes those fences are in yards, but sometimes they encase people’s thoughts and feelings. Without realizing it, we can let the pressures of everyday living so dominate our attention that the fundamental needs of our dogs get neglected. Above all, this implies their social needs. For most dogs, the prime need in their lives is a connection with their owners. To think that as a substitute for that connection you can offer an abundance of toys, free rein of the house, or a seemingly unlimited supply of dog food is the height of self-deception and romantic thinking. Such offerings won’t impress your dog because they ignore what he most truly values: time with you. Watch out for the fences you erect between you and your dog. You’ll both be happier without them. We guarantee it.

Mission of Mercy

Finally, still another sure way to build the relationship between you and your dog—and contribute to the greater good in the process—is to visit someone who is elderly or ill. Although some dogs are a better fit for this than others, and specialized training may be needed, many breeds and mixes have an innate ability to soothe people in physical or mental distress. Dogs can be medicine for the body and soul. One only needs to look at the transforming effect a therapy dog can have. Such dogs can truly work miracles.

MARC Bobbi was a big white greyhound and a registered therapy dog. We made many visits together to hospitals and nursing homes to comfort the patients. On one of these trips, we visited a hospital for profoundly brain-damaged children. It was there we met Danny.

Eight years old, Danny had sustained a brain injury that had rendered him in a nearly vegetative state. He couldn’t sit up by himself, so when I brought Bobbi to see him, a nurse had to prop Danny up. Bobbi nudged the boy’s hand, but Danny did not respond. I thought Bobbi would then solicit attention from the nurse instead. But she did not. Bobbi lay down next to the child and rested her head in Danny’s lap. Then she promptly fell asleep.

No one dared disturb her, and Bobbi must have slept for a full ten minutes. Then she awakened, stood, and shook herself.

“He’s smiling,” the nurse said with tears in her eyes.

The nurse had known Danny before the injury. His family lived in her neighborhood. She told me that Danny was the type of child who smiled all the time. Even after the injury, he would smile now and then. Over the past few weeks, however, his condition had worsened and he showed no communicative ability at all.

That is, until Bobbi lay on his lap.

Any well-behaved dog may be a welcome visitor for an elderly or sick friend or relative.

BROTHER CHRISTOPHER Before my mother died, she was an Alzheimer’s patient at a health care facility near the monastery. I had the opportunity to bring my dog Zoe to the unit for visits. It never ceased to amaze me how not only my mother but also a number of the other residents responded to Zoe. Somehow Zoe was able to offer a simple comforting presence that elicited real affection. What I think is that Zoe pierced through the ordinary human defenses that some people set up after experiencing phoniness and deceit in their human relationships. Even Alzheimer’s patients do this. They learn not always to trust the “face” another individual presents to them. With a dog it is different. Dogs don’t lie: What you see is what you get, and for that reason dogs have a unique ability to lift the spirits of patients and touch them in a way that even human visitors do not.

At the risk of anthropomorphizing dogs, it seems fair to say that dogs see the nature of man more clearly than we see the essence of dog. Many dogs, despite their lack of Hollywood perfection, sense a human need for comfort. And they respond in remarkable ways, enchanting us with their natural gifts. Dogs don’t need to live up to the expectations created by Lassie for us to love them. Let dogs be dogs, and at the same time, let us embrace our role in helping them truly become themselves.