3

ORGANIZING OUR HOMES

Where Things Can Start to Get Better

Few of us feel that our homes or work spaces are perfectly organized. We lose our car keys, an important piece of mail; we go shopping and forget something we needed to buy; we miss an appointment we thought we’d be sure to remember. In the best case, the house is neat and tidy, but our drawers and closets are cluttered. Some of us still have unpacked boxes from our last move (even if it was five years ago), and our home offices accumulate paperwork faster than we know what to do with it. Our attics, garages, basements, and the junk drawers in our kitchens are in such a state that we hope no one we know ever takes a peek inside of them, and we fear the day we may need to actually find something there.

These are obviously not problems that our ancestors had. When you think about what your ancestors might have lived like a thousand years ago, it’s easy to focus on the technological differences—no cars, electricity, central heating, or indoor plumbing. It’s tempting to picture homes as we know them now, meals more or less the same except for the lack of prepackaged food. More grinding of wheat and skinning of fowl, perhaps. But the anthropological and historical record tells a very different story.

In terms of food, our ancestors tended to eat what they could get their hands on. All kinds of things that we don’t eat today, because they don’t taste very good by most accounts, were standard fare only because they were available: rats, squirrels, peacocks—and don’t forget locusts! Some foods that we consider haute cuisine today, such as lobster, were so plentiful in the 1800s that they were fed to prisoners and orphans, and ground up into fertilizer; servants requested written assurance that they would not be fed lobster more than twice a week.

Things that we take for granted—something as basic as the kitchen—didn’t exist in European homes until a few hundred years ago. Until 1600, the typical European home had a single room, and families would crowd around the fire most of the year to keep warm. The number of possessions the average person has now is far greater than we had for most of our evolutionary history, easily by a factor of 1,000, and so organizing them is a distinctly modern problem. One American household studied had more than 2,260 visible objects in just the living room and two bedrooms. That’s not counting items in the kitchen and garage, and all those that were tucked inside a drawer, cabinet, or in boxes. Including those, the number could easily be three times as high. Many families amass more objects than their houses can hold. The result is garages given over to old furniture and unused sports equipment, home offices cluttered with boxes of stuff that haven’t yet been taken to the garage. Three out of four Americans report their garages are too full to put a car into them. Women’s cortisol levels (the stress hormone) spike when confronted with such clutter (men’s, not so much). Elevated cortisol levels can lead to chronic cognitive impairment, fatigue, and suppression of the body’s immune system.

Adding to the stress is that many of us feel organizing our possessions has gotten away from us. Bedside tables are piled high with stuff. We don’t even remember what’s in those unpacked boxes. The TV remote needs a new battery, but we don’t know where the new batteries are. Last year’s bills are piled high on the desk of our home office. Few of us feel that are homes are as well organized as, say, Ace Hardware. How do they do it?

The layout and organization of products on shelves in a well-designed hardware store exemplify the principles outlined in the previous chapters. It practices putting together conceptually similar objects, putting together functionally associated objects, and all the while maintaining cognitively flexible categories.

John Venhuizen is president and CEO of Ace Hardware, a retailer with more than 4,300 stores in the United States. “Anyone who takes retailing and marketing seriously has a desire to know more about the human brain,” he says. “Part of what makes the brain get cluttered is capacity—it can only absorb and decipher so much. Those big box stores are great retailers and we can learn a lot from them, but our model is to strive for a smaller, navigable store because it is easier on the brain of our customers. This is an endless pursuit.” Ace, in other words, employs the use of flexible categories to create cognitive economy.

Ace employs an entire category-management team that strives to arrange the products on the shelves in a way that mirrors the way consumers think and shop. A typical Ace store carries 20,000–30,000 different items, and the chain as a whole inventories 83,000 different items. (Recall from Chapter 1 that there are an estimated one million SKUs in the United States. This means that the Ace Hardware chain stocks nearly 10% of all the available products in the country.)

Ace categorizes its items hierarchically into departments, such as lawn & garden, plumbing, electrical, and paint. Then, beneath those categories are subdivisions such as fertilizers, irrigation, and tools (under lawn & garden), or fixtures, wire, and bulbs (under electrical). The hierarchy digs down deep. Under the Hand & Power Tools Department, Ace lists the following, nested subcategories:

- Power Tools

- Consumer Power Tools | Heavy-Duty Power Tools | Wet/Dry Vacs

- Corded Drills

- Craftsman

- Black & Decker

- Makita

- And so on

What works for inventory control, however, isn’t necessarily what works for shelving and display purposes. “We learned long ago,” Venhuizen says, “that hammers sell with nails because when the customer is buying nails and they see a hammer on the shelf, it reminds them that they need a new one. We used to rigidly keep the hammers with other hand tools; now we put a few with the nails for just that reason.”

Suppose you want to repair a loose board in your fence and you need a nail. You go to the hardware store, and typically there will be an entire aisle for fasteners (the superordinate category). Nails, screws, bolts, and washers (basic-level categories) take up a single aisle, and within that aisle are hierarchical subdivisions with subsections for concrete nails, drywall nails, wood nails, carpet tacks (the subordinate categories).

Suppose now that you want to buy laundry line. This is a type of rope with special properties: It has to be made of a material that won’t stain wet clothes; it has to be able to be left outside permanently and so must withstand the elements; it has to have the tensile strength to hold a load of laundry without breaking or stretching too much. Now, you could imagine that the hardware store would have a single aisle for rope, string, twine, cord, and cable, where all of these like things are kept together (as with nails), and they do, but the merchants leverage our brains’ associative memory networks by also placing a stock of laundry line near the Tide detergent, ironing boards, irons, and clothespins. That is, some laundry line is kept with “things you need to do your laundry,” a functional category that mirrors the way the brain organizes information. This makes it easy not just to find the product you want, but to remember that you need it.

How about clothing retailers organizing their stock? They tend to use a hierarchical system, too, like Ace Hardware. They may also use functional categories, putting rainwear in one section, sleepwear in another. The categorization problem for a clothing retailer is this: There are at least four important dimensions on which their stock differs—the gender of the intended buyer, the kind of clothing (pants, shirts, socks, hats, etc.), color, and size. Clothing stores typically put the pants in one section and the shirts in another, and so on. Then, dropping down a level in the hierarchy, dress shirts are separated from sports shirts and T-shirts. Within the pants department, the stock tends to be arranged by size. If a department employee has been especially punctilious in reordering after careless browsers have gone through the stock, within each size category the pants are arranged by color. Now it gets a bit more complicated because men’s pants are sized using two numbers, the waist and the inseam length. In most clothing stores, the waist is the categorization number: All the pants of a particular waist size are grouped together. So you walk into the Gap, you ask for the pants department, and you’re directed to the back of the store, where you find rows and rows of square boxes containing thousands of pairs of pants. Right away you notice a subdivision. The jeans are probably stocked separately from the khakis, which are stocked separately from any other sporty, dressy, or more upscale pants.

Now, all the jeans with a 34-inch waist will be clearly marked on the shelf. As you look through them, the inseam lengths should be in increasing order. And color? It depends on the store. Sometimes, all the black jeans are in one contiguous set of shelves, all the blue are in another. Sometimes, within a size category, all the blues are stacked on top of all the blacks, or they’re intermixed. The nice thing about color is that it is easy to spot—it pops out because of your attentional filter (the Where’s Waldo? network)—and so, unlike size, you don’t have to hunt for a tiny label to see what color you’ve got. Note that the shelving is hierarchical and also divided. Men’s clothes are in one part of the store and women’s in another. It makes sense because this is usually a coarse division of the “selection space” in that, most of the time, the clothes we want are in one gender category or the other and we don’t find ourselves hopping back and forth between them.

Of course not all stores are so easy to navigate for customers. Department stores often organize by designer—Ralph Lauren is here, Calvin Klein is there, Kenneth Cole is one row beyond—then within designer, they re-sort to implement a hierarchy, grouping clothes first by type (pants versus shirts) and then by color and/or size. The makeup counters in department stores tend to be vendor driven—Lancôme, L’Oréal, Clinique, Estée Lauder, and Dior each have their own counter. This doesn’t make it easy for the shopper looking for a particular shade of red lipstick to match a handbag. Few shoppers walk into Macy’s thinking, “I’ve just got to get a Clinique red.” It’s terribly inconvenient racing back and forth between one area of the store and another. But the reason Macy’s does it this way is because they rent out the floor space to the different makeup companies. The Lancôme counter at Macy’s is a miniature store-within-a-store and the salespeople work for Lancôme. Lancôme provides the fixtures and the inventory, and Macy’s doesn’t have to worry about keeping the shelves organized or ordering new products; they simply take a small part of the profits from each transaction.

Our homes are not typically as well organized as, say, Ace Hardware, the Gap, or the Lancôme counter. There is the world driven by market forces in which people are paid to keep things organized, and then there is your home.

One solution is to put systems in place at home that will tame the mess—an infrastructure for keeping track of things, sorting them, placing them in locations where they will be found and not lost. The task of organizational systems is to provide maximum information with the least cognitive effort. The problem is that putting systems in place for organizing our homes and work spaces is a daunting task; we fear they’ll take too much time and energy to initiate, and that, like a New Year’s Day diet resolution, we won’t be able to stick with them for long. The good news is that, to a limited extent, all of us already have organizational systems in place that protect us from the creeping chaos that surrounds us. We seldom lose forks and knives because we have a silverware drawer in the kitchen where such things go. We don’t lose our toothbrushes because they are used in a particular room and have a particular place to be stored there. But we do lose bottle openers when we carry them from the kitchen to the rec room or the living room and then forget where they last were. The same thing happens to hairbrushes if we are in the habit of taking them out of the bathroom.

A great deal of losing things then arises from structural forces—the various nomadic things of our lives not being confined to a certain location as is the lowly toothbrush. Take reading glasses—we carry them with us from room to room, and they are easily misplaced because they have no designated place. The neurological foundation of this is now well understood. We evolved a specialized brain structure called the hippocampus just for remembering the spatial location of things. This was tremendously important throughout our evolutionary history for keeping track of where food and water could be found, not to mention the location of various dangers. The hippocampus is such an important center for place memory that it’s found even in rats and mice. A squirrel burying nuts? It’s his hippocampus that helps him retrieve nuts several months later from hundreds of different locations.

In a paper now famous among neuroscientists, the hippocampus was studied in a group of London taxi drivers. All London taxi drivers are required to take a knowledge test of routes throughout the city, and preparation can take three or four years of study. Driving a taxi in London is especially difficult because it is not laid out on a grid system like most American cities; many streets are discontinuous, stopping and starting up again with the same name some distance away, and many streets are one-way or can be accessed only by limited routes. To be an effective taxi driver in London requires superior spatial (place) memory. Across several experiments, neuroscientists found that the hippocampus in London taxi drivers was larger than in other people of comparable age and education—it had increased in volume due to all the location information they needed to keep track of. More recently, we’ve discovered that there are dedicated cells in the hippocampus (called dentate granule cells) to encode memories for specific places.

Place memory evolved over hundreds of thousands of years to keep track of things that didn’t move, such as fruit trees, wells, mountains, lakes. It’s not only vast but exquisitely accurate for stationary things that are important to our survival. What it’s not so good at is keeping track of things that move from place to place. This is why you remember where your toothbrush is but not your glasses. It’s why you lose your car keys but not your car (there are an infinity of places to leave your keys around the house, but relatively fewer places to leave the car). The phenomenon of place memory was known already to the ancient Greeks. The famous mnemonic system they devised, the method of loci, relies on our being able to take concepts we want to remember and attach them to our vivid memories of well-known spaces, such as the rooms in our home.

Recall the Gibsonian affordances from Chapter 1, ways that our environment can serve as mental aids or cognitive enhancers. Simple affordances for the objects of our lives can rapidly ease the mental burden of trying to keep track of where they are, and make keeping them in place—taming their wandering ways—aesthetically and emotionally pleasing. We can think of these as cognitive prosthetics. For keys, a bowl or hook near the door you usually use solves the problem (featured in Dr. Zhivago and The Big Bang Theory). The bowl or hook can be decorative, to match the decor of the room. The system depends on being compulsive about it. Whenever you are home, that is where the keys should be. As soon as you walk in the door, you hang them there. No exceptions. If the phone is ringing, hang the keys up first. If your hands are full, put the packages down and hang up those keys! One of the big rules in not losing things is the rule of the designated place.

A tray or shelf that is designated for a smartphone encourages you to put your phone there and not somewhere else. The same is true for other electronic objects and the daily mail. Sharper Image, Brookstone, SkyMall, and the Container Store have made a business model out of this neurological reality, featuring products spanning an amazing range of styles and price points (plastic, leather, or sterling silver) that function as affordances for keeping your wayward objects in their respective homes. Cognitive psychology theory says spend as much as you can on these: It’s very difficult to leave your mail scattered about when you’ve spent a lot of money for a special tray to keep it in.

But simple affordances don’t always require purchasing new stuff. If your books, CDs, or DVDs are organized and you want to remember where to put back the one you just took out, you can pull out the one just to the left of it about an inch and then it becomes an affordance for you to easily see where to put back the one you “borrowed” from your library. Affordances aren’t just for people with bad memories, or people who have reached their golden years—many people, even young ones with exceptional memories, report that they have trouble keeping track of everyday items. Magnus Carlsen is the number one rated chess player in the world at only twenty-three years old. He can keep ten games going at once just in his memory—without looking at the board—but, he says, “I forget all kinds of [other] stuff. I regularly lose my credit cards, my mobile phone, keys, and so on.”

B. F. Skinner, the influential Harvard psychologist and father of behaviorism, as well as a social critic through his writings, including Walden Two, elaborated on the affordance. If you hear on the weather report in the evening that it’s supposed to rain tomorrow, he said, put an umbrella near the front door so you won’t forget to take it. If you have letters to mail, put them near your car keys or house keys so that when you leave the house, they’re right there. The principle underlying all these is off-loading the information from your brain and into the environment; use the environment itself to remind you of what needs to be done. Jeffrey Kimball, formerly a vice president of Miramax and now an award-winning independent filmmaker, says, “If I know I might forget something when I leave the house, I put it in or next to my shoes by the front door. I also use the ‘four’ system—every time I leave the house I check that I have four things: keys, wallet, phone, and glasses.”

If you’re afraid you’ll forget to buy milk on the way home, put an empty milk carton on the seat next to you in the car or in the backpack you carry to work on the subway (a note would do, of course, but the carton is more unusual and so more apt to grab your attention). The other side to leaving physical objects out as reminders is to put them away when you don’t need them. The brain is an exquisite change detector and that’s why you notice the umbrella by the door or the milk carton on the car seat. But a corollary to that is that the brain habituates to things that don’t change—this is why a friend can walk into your kitchen and notice that the refrigerator has developed an odd humming noise, something you no longer notice. If the umbrella is by the door all the time, rain or shine, it no longer functions as a memory trigger, because you don’t notice it. To help remember where you parked your car, parking lot signs at the San Francisco airport recommend taking a cell phone photo of your spot. Of course this works for bicycle parking as well. (In the new heart of the tech industry, Google cars and Google Glass will probably be doing this for us soon enough.)

When organized people find themselves running between the kitchen and the home office all the time to get a pair of scissors, they buy an extra pair. It might seem like cluttering rather than organizing, but buying duplicates of things that you use frequently and in different locations helps to prevent you from losing them. Perhaps you use your reading glasses in the bedroom, the home office, and the kitchen. Three pairs solves the problem if you can create a designated place for them, a special spot in each room, and always leave them there. Because the reading glasses are no longer moving from room to room, your place memory will help you recall within each room where they are. Some people buy an extra set for the glove compartment of the car to read maps, and put another pair in their purse or jacket to have when they’re at a restaurant and need to read the menu. Of course prescription reading glasses can be expensive, and three pairs all the more so. Alternatively, a tether for the reading glasses, a neck cord, keeps them with you all the time. (Contrary to the frequently observed correlation, there is no scientific evidence that these little spectacle lanyards make your hair go gray or create an affinity for cardigans.) The neurological principle remains. Be sure that when you untether them, they go back to their one spot; the system collapses if you have several spots.

Either one of these overall strategies—providing duplicates or creating a rigidly defined special spot—works well for many everyday items: lipstick, hair scrunchies, pocketknives, bottle openers, staplers, Scotch tape, scissors, hairbrushes, nail files, pens, pencils, and notepads. The system doesn’t work for things you can’t duplicate, like your keys, computer, iPad, the day’s mail, or your cell phone. For these, the best strategy is to harness the power of the hippocampus rather than trying to fight it: Designate a specific location in your house that will be home to these objects. Be strict about adhering to it.

Many people may be thinking, “Oh, I’m just not a detail-oriented person like that—I’m a creative person.” But a creative mind-set is not antithetical to this kind of organization. Joni Mitchell’s home is a paragon of organizational systems. She installed dozens of custom-designed, special-purpose drawers in her kitchen to better organize just exactly the kinds of things that tend to be hard to locate. One drawer is for rolls of Scotch tape, another for masking tape. One drawer is for mailing and packing products; another for string and rope; another for batteries (organized by size in little plastic trays); and a particularly deep drawer holds spare lightbulbs. Tools and implements for baking are separate from those for sautéing. Her pantry is similarly organized. Crackers on one shelf, cereal on another, soup ingredients on a third, canned goods on a fourth. “I don’t want to waste energy looking for things,” she says. “What good is that? I can be more efficient, productive and in a better mood if I don’t spend those frustrating extra minutes searching for something.” Thus, in fact, many creative people find the time to be creative precisely because of such systems unburdening and uncluttering their minds.

A large proportion of successful rock and hip-hop musicians have home studios, and despite the reputation they may have for being anything-goes, hard-drinking rebels, their studios are meticulously organized. Stephen Stills’s home studio has designated drawers for guitar strings, picks, Allen wrenches, jacks, plugs, equipment spare parts (organized by type of equipment), splicing tape, and so on. A rack for cords and cables (it looks something like a necktie rack) holds electrical and musical instrument cords of various types in a particular order so that he can grab what he needs even without looking. Michael Jackson fastidiously catalogued every one of his possessions; among the large staff he employed was someone with the job title chief archivist. John Lennon kept boxes and boxes of work tapes of songs in progress, carefully labeled and organized.

There’s something almost ineffably comforting about opening a drawer and seeing things all of one kind in it, or surveying an organized closet. Finding things without rummaging saves mental energy for more important creative tasks. It is in fact physiologically comforting to avoid the stress of wondering whether or not we’re ever going to find what we’re looking for. Not finding something thrusts the mind into a fog of confusion, a toxic vigilance mode that is neither focused nor relaxed. The more carefully constructed your categories, the more organized is your environment and, in turn, your mind.

From the Junk Drawer to the Filing Cabinet and Back

The fact that our brains are inherently good at creating categories is a powerful lever for organizing our lives. We can construct our home and work environments in such a way that they become extensions of our brains. In doing so, we must accept the capacity limitations of our central executive. The standard account for many years was that working memory and attention hit a limit at around five to nine unrelated items. More recently, a number of experiments have shown that the number is realistically probably closer to four.

The key to creating useful categories in our homes is to limit the number of types of things they contain to one or at most four types of things (respecting the capacity limitations of working memory). This is usually easy to do. If you’ve got a kitchen drawer that contains cocktail napkins, shish kebab skewers, matches, candles, and coasters, you can conceptualize it as “things for a party.” Conceptualizing it that way ties together all these disparate objects at a higher level. And then, if someone gives you special soaps that you want to put out only when you entertain, you know what drawer to keep them in.

Our brains are hardwired to make such categories, and these categories are cognitively flexible and can be arranged hierarchically. That is, there are different levels of resolution for what constitutes a kind, and they are context-dependent. Your bedroom closet probably contains clothes and then is subdivided into specialized categories such as underwear, shirts, socks, pants, and shoes. Those can be further subdivided if all your jeans are in one place and your fancy pants in another. When tidying the house, you might throw anything clothing-related into the closet and perform a finer subsort later. You might put anything tool-related in the garage, separating nails from hammers, screws from screwdrivers at a later time. The important observation is that we can create our own categories, and they’re maximally efficient, neurologically speaking, if we can find a single thread that ties together all the members of a particular category.

David Allen, the efficiency expert, observes that what people usually mean when they say they want to get organized is that they need to get control of their physical and psychic environments. A germane finding in cognitive psychology for gaining that control is to make visible the things you need regularly, and hide things that you don’t. This principle was originally formulated for the design of objects like television remote controls. Set aside your irritation with the number of buttons that remain on those gadgets for a moment—it is clear that you don’t want the button that changes the color balances to be right next to the button that changes channels, where you might press it by mistake. In the best designs, the seldom-used setup controls are hidden behind a flip panel, or at least out of the way of the buttons you use daily.

In organizing your living space, the goals are to off-load some of the memory functions from your brain and into the environment; to keep your environment visually organized, so as not to distract you when you’re trying to relax, work, or find things; and to create designated places for things so that they can be easily located.

Suppose you have limited closet space for your clothes, and some articles of clothing you wear only rarely (tuxedos, evening gowns, ski clothes). Move them to a spare closet so they’re not using up prime real estate and so you can organize your daily clothes more efficiently. The same applies in the kitchen. Rather than putting all your baking supplies in one drawer, it makes organizational sense to put your Christmas cookie cutters in a special drawer devoted to Christmas-y things so you reduce clutter in your daily baking drawer—something you use only two weeks out of the year shouldn’t be in your way fifty weeks out of the year. Keep stamps, envelopes, and stationery together in the same desk drawer because you use them together.

The display of liquor bottles in busy bars and taverns (places that many call home!) follows this principle. The frequently used liquors are within arm’s reach of the bartender in what is called the speed rack attached to the base of the bar; little movement or mental energy is wasted in searching for these when making popular drinks from the speed rack. Less frequently used bottles are off to the side, or on a back shelf. Then, within this system, bottles of like spirits are placed side by side. The three or four most popular bourbons will be within arm’s reach next to one another; the three or four most popular blended Scotches are next to them, and the single malts next to those. The configuration of both what’s in the speed rack and what’s on display will take account of local preferences. A bar in Lexington, Kentucky, would have many well-known brands of bourbon prominently displayed; a college town bar would have more tequila and vodka on display.

In a well-organized system, there is a balance between category size and category specificity. In other words, if you have only a handful of nails, it would be silly to devote an entire drawer just to them. It’s more efficient and practical, then, to combine items into conceptual categories such as “home repair items.” When the number of nails you have reaches critical mass, however, so that you’re spending too much time every Sunday trying to find the precise nail you want, it makes sense to sort them by size into little bins the way they do at the hardware store. Time is an important consideration, too: Do you expect to be using these things more or less in the next few years?

Following Phaedrus, maintain the kind of flexibility that lets you create “everything else” categories—a junk drawer. Even if you have an exquisitely organized system where every drawer, shelf, and cubbyhole in your kitchen, office, or workshop is labeled, there will often be things that just don’t fit into any existing system. Or alternatively, you might have too few things to devote an entire drawer or shelf to. From a purely obsessive-compulsive standpoint, it would be nice to have an entire drawer or shelf devoted to spare lightbulbs, another to adhesives (glue, contact cement, epoxy, double-sided tape), and another to your collection of candles. But if all you have is a single lightbulb and a half- used tube of Krazy Glue, there’s no point.

Two neurologically based steps for setting up home information systems are, first, the categories you create need to reflect how you use and interact with your possessions. That is, the categories have to be meaningful to you. They should take into account your life stage. (All those hand-tied fisherman’s flies that your grandfather left you might stay in the tackle box unsorted until you take up fly-fishing in a few decades, then you’ll want to arrange the flies in a finer-grained way.) Second, avoid putting too many dissimilar items into a drawer or folder unless you can come up with an overarching theme. If you can’t, MISCELLANEOUS or JUNK or UNCLASSIFIABLE are OK. But if you find yourself having four or five junk drawers, it’s time to re-sort and regroup their contents, into MISC HOUSEHOLD versus MISC GARDEN versus MISC KIDS’ STUFF for example.

Beyond those practical personalized steps, follow these general three rules of organization.

Organization Rule 1: A mislabeled item or location is worse than an unlabeled item.

In a burst of energy, Jim labels one drawer in his office STAMPS AND ENVELOPES and another BATTERIES. After a couple of months, he swaps the contents of the drawers because he finds it difficult to bend over and distinguish AAA from AA batteries. He doesn’t swap the labels because it’s too much trouble, and he figures it doesn’t matter because he knows where they are. This is a slippery slope! If you allow two drawers to go mislabeled, it’s only a matter of time before you loosen your grip on creating “a place for everything and everything in its place.” It also makes it difficult for anyone else to find anything. Something that is unlabeled is actually preferable because it causes a conversation such as “Jim, where do you keep your batteries?” or, if Jim isn’t around, a systematic search. With mislabeled drawers, you don’t know which ones you can trust and which ones you can’t.

Organization Rule 2: If there is an existing standard, use it.

Melanie has a recycling bin and a garbage bin under her kitchen sinks. One of them is blue and the other is gray. Outside, the bins that the city sanitation department gave her are blue (for recycling) and gray (for garbage). She should stick with that color-coded system because it is a standard, and then she doesn’t have to try to memorize two different, opposing systems.

Organization Rule 3: Don’t keep what you can’t use.

If you don’t need it or it’s broken and unfixable, get rid of it. Avery picks a ballpoint pen out of her pen drawer, and it doesn’t write. She tries everything she knows to get it to work—moistening the tip, heating it with a lighter, shaking it, and making swirls on a piece of paper. She concludes it doesn’t work, and then puts it right back in the drawer and takes another pen. Why did she (and why do we) do this? Few of us have an accurate knowledge of what makes a pen work or not work. Our efforts to get them to write are rewarded randomly—sometimes we get them working, sometimes we don’t. We put them back in the drawer, thinking to ourselves “Maybe it’ll work next time.” But the clutter of a drawer full of mixed pens, some of which write and some of which don’t, is a brain drain. Better to throw out the nonworking pen. Or, if you just can’t stand the thought of that, designate a special box or drawer for recalcitrant pens that you will attempt to reform someday. If you’re keeping the spare rubber feet that came with your TV set, and the TV set is no longer working, get rid of those rubber feet.

I am assuming people will still be watching something called TV when this book is published.

The Digital Home

Decades of research have shown that human learning is influenced by context and by the location where the learning takes place. Students who studied for an exam in the room they later took it in did better than students who studied somewhere else. We go back to our childhood home after a long absence, and a flood of forgotten memories is released. This is the reason it’s important to have a designated place for each of our belongings—the hippocampus does the remembering for us if we associate an object with a particular spatial location. What happens when the information in the home is substantially, increasingly digital? There are a number of important implications in an age when so many more of us work from home or do office work at home.

One way to exploit the hippocampus’s natural style of memory storage is to create different work spaces for the different kinds of work we do. But we use the same computer screen for balancing our checkbook, responding to e-mails from our boss, making online purchases, watching videos of cats playing the piano, storing photos of our loved ones, listening to our favorite music, paying bills, and reading the daily news. It’s no wonder we can’t remember everything—the brain simply wasn’t designed to have so much information in one place. This advice is probably a luxury for a select few, but soon it will be possible as the cost of computers goes down: If you can, it’s helpful to have one device dedicated to one domain of things. Instead of using your computer for watching videos and listening to music, have a dedicated media device (iPod, iPad). Have one computer for personal business (checking accounts and taxes), and a second computer for personal and leisure activities (planning trips, online purchases, storing photos). And a third computer for work. Create different desktop patterns on them so that the visual cues help to remind you, and put you in the proper place-memory context, of each computer’s domain.

The neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks goes one further: If you’re working on two completely separate projects, dedicate one desk or table or section of the house for each. Just stepping into a different space hits the reset button on your brain and allows for more productive and creative thinking.

Short of owning two or three separate computers, technology now allows for portable pocket drives that hold your entire hard disk—you can plug in a “leisure” pocket drive, a “work” pocket drive, or a “personal finance” pocket drive. Or instead, different user modes on some computers change the pattern of the desktop, the files on it, and the overall appearance to facilitate making these kinds of place-based, hippocampus-driven distinctions.

Which brings us to the considerable amount of information that hasn’t been digitized yet. You know, on that stuff they call paper. Two schools of thought about how to organize the paper-based business affairs of your home are now battling over this area. In this category are included operating manuals for appliances and various electrical or electronic devices, warranties for purchased products and services, paid bills, canceled checks, insurance policies, other daily business documents, and receipts.

Microsoft engineer Malcolm Slaney (formerly of Yahoo!, IBM, and Apple) advocates scanning everything into PDFs and keeping them on your computer. Home scanners are relatively inexpensive, and there are strikingly good scanning apps available on cell phones. If it’s something you want to keep, Malcolm says, scan it and save it under a filename and folder that will help you find it later. Use OCR (optical character recognition) mode so that the PDF is readable as text characters rather than simply a photograph of the file, to allow your computer’s own search function to find specific keywords you’re looking for. The advantage of digital filing is that it takes up virtually no space, is environmentally friendly, and is electronically searchable. Moreover, if you need to share the document with someone (your accountant, a colleague) it’s already in a digital format and so you can simply attach it to an e-mail.

The second school of thought is advocated by someone I’ll call Linda, who for many years served as the executive assistant to the president of a Fortune 100 company. She has asked to remain anonymous to protect the privacy of her boss. (What a great executive assistant!) Linda prefers to keep paper copies of everything. The chief advantage of paper is that it is almost permanent. Because of rapidly changing technology, digital files are rarely readable for more than ten years; paper, on the other hand, lasts for hundreds of years. Many computer users have become alerted to a rude surprise after their old computers failed: It’s often not possible to buy a computer with the old operating system on it, and the new operating system can’t open all your old files! Financial records, tax returns, photos, music—all of it gone. In large cities, it’s possible to find services that will convert your files from old to new formats, but this can be costly, incomplete, and imperfect. Electrons are free, but you get what you pay for.

Other advantages of paper are that it can’t be as easily edited or altered, or corrupted by a virus, and you can read it when the power’s out. And although paper can be destroyed by a fire, so can your computer.

Despite their committed advocacy, even Malcolm and Linda keep many of their files in the nonpreferred format. In some cases, this is because they come to us that way—receipts for online purchases are sent as digital files by e-mail; bills from small companies still arrive by U.S. mail on paper.

There are ways of sorting both kinds of information, digital and paper, that can maximize their usefulness. The most important factor is the ease with which they can be retrieved.

For physical paper, the classic filing cabinet is still the best system known. The state of the art is the hanging file folder system, invented by Frank D. Jonas and patented in 1941 by the Oxford Filing Supply Company, which later became the Oxford Pendaflex Corporation. Oxford and secretarial schools have devised principles for creating file folders, and they revolve around making things easy to store and easy to retrieve. For a small number of files, say fewer than thirty, labeling them and sorting them in alphabetical order by topic is usually sufficient. More than that and you’re usually better off alphabetizing your folders within higher-order categories, such as HOME, FINANCIAL, KIDS, and the like. Use the physical environment to separate such categories—different drawers in the filing cabinet, for example, can contain different higher-order categories; or within a drawer, different colored file folders or file folder tabs make it possible to visually distinguish categories very quickly. Some people, particularly those with attention deficit disorder, panic when they can’t see all of their files in front of them, out in the open. In these cases, open filing carts and racks exist so that the files don’t need to be hidden behind a drawer.

An often-taught practical rule about traditional filing systems (that is, putting paper into hanging file folders) is that you don’t want to have a file folder with only one piece of paper in it—it’s too inefficient. The goal is to group paperwork into categories such that your files contain five to twenty or so separate documents. Fewer than that and it becomes difficult to quickly scan the numerous file folder labels; more than that and you lose time trying to finger through the contents of one file folder. The same logic applies to creating categories for household and work objects.

Setting up a home filing system is more than just slapping a label on a folder. It’s best to have a plan. Take some time to think about what the different kinds of papers are that you’re filing. Take that stack of papers on your desk that you’ve been meaning to do something with for months and start sorting them, creating high-level categories that subsume them. If the sum total of all your file folders is less than, say, twenty, you could just have a folder for each topic and put them in alphabetical order. But more than that, and you’re going to waste time searching for folders when you need them. You might have categories such as FINANCES, HOME STUFF, PERSONAL, MEDICAL, and MISCELLANEOUS (the junk drawer of your system for things that don’t fit anywhere else: pet vaccination records, driver’s license renewal, brochures for that trip you want to take next spring). Paperwork from specific correspondents should get its own folder. In other words, if you have a separate savings account, checking account, and retirement account, you don’t want a folder labeled BANK STATEMENTS; you want folders for each account. The same logic applies across all kinds of objects.

Don’t spend more time filing and classifying than you’ll reap on searching. For documents you need to access somewhat frequently, say health records, make file folders and categories that facilitate finding what you’re looking for—separate folders for each household member, or folders for GENERAL MEDICAL, DENTISTRY, EYE CARE, and so on. If you’ve got a bunch of file folders with one piece of paper in them, consolidate into an overarching theme. Create a dedicated file for important documents you need regularly to access, such as a visa, birth certificate, or health insurance policy.

All of the principles that apply to physical file folders of course also apply to the virtual files and folders on your computer. The clear advantage of the computer, however, is that you can keep your files entirely unorganized and the search function will usually help you find them nearly instantly (if you can remember what you named them). But this imposes a burden on your memory—it requires that you register and recall every filename you’ve ever used. Hierarchically organized files and folders have the big advantage that you can browse them to rediscover files you had forgotten about. This externalizes the memory from your brain to the computer.

If you really embrace the idea of making electronic copies of your important documents, you can create tremendously flexible relational databases and hyperlinks. For example, suppose you do your personal accounting in Excel and you’ve scanned all of your receipts and invoices to PDF files. Within Excel, you can link any entry in a cell to a document on your computer. Looking for the warranty and receipt on your Orvis fishing tackle jacket? Search Excel for Orvis, click on the cell, and you have the receipt ready to e-mail to the Customer Service Department. It’s not just financial documents that can be linked this way. In a Word document in which you’re citing research papers, you can create live links to those papers on your hard disk, a company server, or in the cloud.

Doug Merrill, former chief information officer and VP of engineering at Google, says “organization isn’t—nor should it be—the same for everybody.” However, there are fundamental things like To Do lists and carrying around notepaper or index cards, or “putting everything in a certain place and remembering where that place is.”

But wait—even though many of us have home offices and pay our bills at home, all this doesn’t sound like home. Home isn’t about filing. What do you love about being at home? That feeling of calm, secure control over how you spend your time? What do you do at home? If you’re like most Americans, you are multitasking. That buzzword of the aughts doesn’t happen just on the job anymore. The smartphones and tablets have come home to roost.

Our cell phones have become Swiss Army knife–like appliances that include a dictionary, calculator, Web browser, e-mail client, Game Boy, appointment calendar, voice recorder, guitar tuner, weather forecaster, GPS, texter, tweeter, Facebook updater, and flashlight. They’re more powerful and do more things than the most advanced computer at IBM corporate headquarters thirty years ago. And we use them all the time, part of a twenty-first-century mania for cramming everything we do into every single spare moment of downtime. We text while we’re walking across the street, catch up on e-mail while standing in line, and while having lunch with friends, we surreptitiously check to see what our other friends are doing. At the kitchen counter, cozy and secure in our domicile, we write our shopping lists on smartphones while we are listening to that wonderfully informative podcast on urban beekeeping.

But there’s a fly in the ointment. Although we think we’re doing several things at once, multitasking, this has been shown to be a powerful and diabolical illusion. Earl Miller, a neuroscientist at MIT and one of the world experts on divided attention, says that our brains are “not wired to multi-task well. . . . When people think they’re multi-tasking, they’re actually just switching from one task to another very rapidly. And every time they do, there’s a cognitive cost in doing so.” So we’re not actually keeping a lot of balls in the air like an expert juggler; we’re more like a bad amateur plate spinner, frantically switching from one task to another, ignoring the one that is not right in front of us but worried it will come crashing down any minute. Even though we think we’re getting a lot done, ironically, multitasking makes us demonstrably less efficient.

Multitasking has been found to increase the production of the stress hormone cortisol as well as the fight-or-flight hormone adrenaline, which can overstimulate your brain and cause mental fog or scrambled thinking. Multitasking creates a dopamine-addiction feedback loop, effectively rewarding the brain for losing focus and for constantly searching for external stimulation. To make matters worse, the prefrontal cortex has a novelty bias, meaning that its attention can be easily hijacked by something new—the proverbial shiny objects we use to entice infants, puppies, and kittens. The irony here for those of us who are trying to focus amid competing activities is clear: The very brain region we need to rely on for staying on task is easily distracted. We answer the phone, look up something on the Internet, check our e-mail, send an SMS, and each of these things tweaks the novelty-seeking, reward-seeking centers of the brain, causing a burst of endogenous opioids (no wonder it feels so good!), all to the detriment of our staying on task. It is the ultimate empty-caloried brain candy. Instead of reaping the big rewards that come from sustained, focused effort, we instead reap empty rewards from completing a thousand little sugarcoated tasks.

In the old days, if the phone rang and we were busy, we either didn’t answer or we turned the ringer off. When all phones were wired to a wall, there was no expectation of being able to reach us at all times—one might have gone out for a walk or be between places, and so if someone couldn’t reach you (or you didn’t feel like being reached), that was considered normal. Now more people have cell phones than have toilets. This has created an implicit expectation that you should be able to reach someone when it is convenient for you, regardless of whether it is convenient for them. This expectation is so ingrained that people in meetings routinely answer their cell phones to say, “I’m sorry, I can’t talk now, I’m in a meeting.” Just a decade or two ago, those same people would have let a landline on their desk go unanswered during a meeting, so different were the expectations for reachability.

Just having the opportunity to multitask is detrimental to cognitive performance. Glenn Wilson of Gresham College, London, calls it infomania. His research found that being in a situation where you are trying to concentrate on a task, and an e-mail is sitting unread in your inbox, can reduce your effective IQ by 10 points. And although people claim many benefits to marijuana, including enhanced creativity and reduced pain and stress, it is well documented that its chief ingredient, cannabinol, activates dedicated cannabinol receptors in the brain and interferes profoundly with memory and with our ability to concentrate on several things at once. Wilson showed that the cognitive losses from multitasking are even greater than the cognitive losses from pot smoking.

Russ Poldrack, a neuroscientist at Stanford, found that learning information while multitasking causes the new information to go to the wrong part of the brain. If students study and watch TV at the same time, for example, the information from their schoolwork goes into the striatum, a region specialized for storing new procedures and skills, not facts and ideas. Without the distraction of TV, the information goes into the hippocampus, where it is organized and categorized in a variety of ways, making it easier to retrieve it. MIT’s Earl Miller adds, “People can’t do [multitasking] very well, and when they say they can, they’re deluding themselves.” And it turns out the brain is very good at this deluding business.

Then there are the metabolic costs of switching itself that I wrote about earlier. Asking the brain to shift attention from one activity to another causes the prefrontal cortex and striatum to burn up oxygenated glucose, the same fuel they need to stay on task. And the kind of rapid, continual shifting we do with multitasking causes the brain to burn through fuel so quickly that we feel exhausted and disoriented after even a short time. We’ve literally depleted the nutrients in our brain. This leads to compromises in both cognitive and physical performance. Among other things, repeated task switching leads to anxiety, which raises levels of the stress hormone cortisol in the brain, which in turn can lead to aggressive and impulsive behaviors. By contrast, staying on task is controlled by the anterior cingulate and the striatum, and once we engage the central executive mode, staying in that state uses less energy than multitasking and actually reduces the brain’s need for glucose.

To make matters worse, lots of multitasking requires decision-making: Do I answer this text message or ignore it? How do I respond to this? How do I file this e-mail? Do I continue what I’m working on now or take a break? It turns out that decision-making is also very hard on your neural resources and that little decisions appear to take up as much energy as big ones. One of the first things we lose is impulse control. This rapidly spirals into a depleted state in which, after making lots of insignificant decisions, we can end up making truly bad decisions about something important. Why would anyone want to add to their daily weight of information processing by trying to multitask?

In discussing information overload with Fortune 500 leaders, top scientists, writers, students, and small business owners, e-mail comes up again and again as a problem. It’s not a philosophical objection to e-mail itself, it’s the mind-numbing amount of e-mails that comes in. When the ten-year-old son of my neuroscience colleague Jeff Mogil was asked what his father does for a living, he responded, “He answers e-mails.” Jeff admitted after some thought that it’s not so far from the truth. Workers in government, the arts, and industry report that the sheer volume of e-mail they receive is overwhelming, taking a huge bite out of their day. We feel obligated to answer our e-mails, but it seems impossible to do so and get anything else done.

Before e-mail, if you wanted to write to someone, you had to invest some effort in it. You’d sit down with pen and paper, or at a typewriter, and carefully compose a message. There wasn’t anything about the medium that lent itself to dashing off quick notes without giving them much thought, partly because of the ritual involved, and the time it took to write a note, find and address an envelope, add postage, and walk the letter to a mailbox. Because the very act of writing a note or letter to someone took this many steps, and was spread out over time, we didn’t go to the trouble unless we had something important to say. Because of e-mail’s immediacy, most of us give little thought to typing up any little thing that pops in our heads and hitting the send button. And e-mail doesn’t cost anything. Sure, there’s the money you paid for your computer and your Internet connection, but there is no incremental cost to sending one more e-mail. Compare this with paper letters. Each one incurred the price of the envelope and the postage stamp, and although this doesn’t represent a lot of money, these were in limited supply—if you ran out of them, you’d have to make a special trip to the stationery store and the post office to buy more, so you didn’t use them frivolously. The sheer ease of sending e-mails has led to a change in manners, a tendency to be less polite about what we ask of others. Many professionals tell a similar story. Said one, “A large proportion of e-mails I receive are from people I barely know asking me to do something for them that is outside what would normally be considered the scope of my work or my relationship with them. E-mail somehow apparently makes it OK to ask for things they would never ask by phone, in person, or in snail mail.”

There are also important differences between snail mail and e-mail on the receiving end. In the old days, the only mail we got came once a day, which effectively created a cordoned-off section of your day to collect it from the mailbox and sort it. Most importantly, because it took a few days to arrive, there was no expectation that you would act on it immediately. If you were engaged in another activity, you’d simply let the mail sit in the box outside or on your desk until you were ready to deal with it. It even seemed a bit odd to race out to the mailbox to get your mail the moment the letter carrier left it there. (It had taken days to get this far, why would a few more minutes matter?) Now e-mail arrives continuously, and most e-mails demand some sort of action: Click on this link to see a video of a baby panda, or answer this query from a coworker, or make plans for lunch with a friend, or delete this e-mail as spam. All this activity gives us a sense that we’re getting things done—and in some cases we are. But we are sacrificing efficiency and deep concentration when we interrupt our priority activities with e-mail.

Until recently, each of the many different modes of communication we used signaled its relevance, importance, and intent. If a loved one communicated with you via a poem or a song, even before the message was apparent, you had a reason to assume something about the nature of the content and its emotional value. If that same loved one communicated instead via a summons, delivered by an officer of the court, you would have expected a different message before even reading the document. Similarly, phone calls were typically used to transact different business from that of telegrams or business letters. The medium was a clue to the message. All of that has changed with e-mail, and this is one of its overlooked disadvantages—because it is used for everything. In the old days, you might sort all of your postal mail into two piles, roughly corresponding to personal letters and bills. If you were a corporate manager with a busy schedule, you might similarly sort your telephone messages for callbacks. But e-mails are used for all of life’s messages. We compulsively check our e-mail in part because we don’t know whether the next message will be for leisure/amusement, an overdue bill, a “to do,” a query . . . something you can do now, later, something life-changing, something irrelevant.

This uncertainty wreaks havoc with our rapid perceptual categorization system, causes stress, and leads to decision overload. Every e-mail requires a decision! Do I respond to it? If so, now or later? How important is it? What will be the social, economic, or job-related consequences if I don’t answer, or if I don’t answer right now?

Now of course e-mail is approaching obsolescence as a communicative medium. Most people under the age of thirty think of e-mail as an outdated mode of communication used only by “old people.” In its place they text, and some still post to Facebook. They attach documents, photos, videos, and links to their text messages and Facebook posts the way people over thirty do with e-mail. Many people under twenty now see Facebook as a medium for the older generation. For them, texting has become the primary mode of communication. It offers privacy that you don’t get with phone calls, and immediacy you don’t get with e-mail. Crisis hotlines have begun accepting calls from at-risk youth via texting and it allows them two big advantages: They can deal with more than one person at a time, and they can pass the conversation on to an expert, if needed, without interrupting the conversation.

But texting sports most of the problems of e-mail and then some. Because it is limited in characters, it discourages thoughtful discussion or any level of detail. And the addictive problems are compounded by texting’s hyperimmediacy. E-mails take some time to work their way through the Internet, through switches and routers and servers, and they require that you take the step of explicitly opening them. Text messages magically appear on the screen of your phone and demand immediate attention from you. Add to that the social expectation that an unanswered text feels insulting to the sender, and you’ve got a recipe for addiction: You receive a text, and that activates your novelty centers. You respond and feel rewarded for having completed a task (even though that task was entirely unknown to you fifteen seconds earlier). Each of those delivers a shot of dopamine as your limbic system cries out “More! More! Give me more!”

In a famous experiment, my McGill colleague Peter Milner and James Olds placed a small electrode in the brains of rats, in a small structure of the limbic system called the nucleus accumbens. This structure regulates dopamine production and is the region that “lights up” when gamblers win a bet, drug addicts take cocaine, or people have orgasms—Olds and Milner called it the pleasure center. A lever in the cage allowed the rats to send a small electrical signal directly to their nucleus accumbens. Do you think they liked it? Boy howdy! They liked it so much that they did nothing else. They forgot all about eating and sleeping. Long after they were hungry, they ignored tasty food if they had a chance to press that little chrome bar; they even ignored the opportunity for sex. The rats just pressed the lever over and over again, until they died of starvation and exhaustion. Does that remind you of anything? A thirty-year-old man died in Guangzhou (China) after playing video games continuously for three days. Another man died in Daegu (Korea) after playing video games almost continuously for fifty hours, stopped only by his going into cardiac arrest.

Each time we dispatch with an e-mail in one way or another, we feel a sense of accomplishment, and our brain gets a dollop of reward hormones telling us we accomplished something. Each time we check a Twitter feed or Facebook update, we encounter something novel and feel more connected socially (in a kind of weird impersonal cyber way) and get another dollop of reward hormones. But remember, it is the dumb, novelty-seeking portion of the brain driving the limbic system that induces this feeling of pleasure, not the planning, scheduling, higher-level thought centers in the prefrontal cortex. Make no mistake: E-mail, Facebook, and Twitter checking constitute a neural addiction.

The secret is to put systems in place to trick ourselves—to trick our brains—into staying on task when we need them to. For one, set aside certain times of day when you’ll do e-mail. Experts recommend that you do e-mail only two or three times a day, in concerted clumps rather than as they come in. Many people have their e-mail programs set to put through arriving e-mails automatically or to check every five minutes. Think about that: If you’re checking e-mail every five minutes, you’re checking it 200 times during the waking day. This has to interfere with advancing your primary objectives. You might have to train your friends and coworkers not to expect immediate responses, to use some other means of communication for things like a meeting later today, a lunch date, or a quick question.

For decades, efficient workers would shut their doors and turn off their phones for “productivity hours,” a time when they could focus without being disturbed. Turning off our e-mail follows in that tradition and it does soothe the brain, both neurochemically and neuroelectrically. If the type of work you do really and truly doesn’t allow for this, you can set up e-mail filters in most e-mail programs and phones, designating certain people whose mail you want to get through to you right away, while other mail just accumulates in your inbox until you have time to deal with it. And for people who really can’t be away from e-mail, another effective trick is to set up a special, private e-mail account and give that address only to those few people who need to be able to reach you right away, and check your other accounts only at designated times.

Lawrence Lessig, a law professor at Harvard, and others have promoted the idea of e-mail bankruptcy. At a certain point, you realize that you’re never going to catch up. When this happens, you delete or archive everything in your inbox, and then send out a mass e-mail to all your correspondents, explaining that you’re hopelessly behind in e-mail and that if whatever they were e-mailing you about is still important, they should e-mail you again. Alternatively, some people set up an automatic reply that gets sent in response to any incoming e-mail message. The reply might say something along the lines of “I will try to get to your e-mail within the next week. If this is something that requires immediate action, please telephone me. If it still requires my reply and you haven’t heard from me in a week, please resend your message with ‘2nd attempt’ in the subject line.”

As shadow work increases and we are called upon to do more of our own personal business management, the need to have accounts with multiple companies has mushroomed. Keeping track of your login information and passwords is difficult because different websites and service providers impose wildly different restrictions on these parameters. Some providers insist that you use your e-mail address as a login, others insist you don’t; some require that your password contains special characters such as $&*#, and others won’t allow any at all. Additional restrictions include not being able to repeat a character more than twice (so that aaa would not be allowed in your password string anywhere) or not being allowed to use the same password you’ve used in the past six months. Even if logins and passwords could be standardized, however, it would be a bad idea to use the same login and password for all your accounts because if one account gets compromised, then all of them do.

Several programs exist for keeping track of your passwords. Many of them store the information on servers (in the cloud), which poses a potential security threat—it’s only a matter of time before hackers break in and steal millions of passwords. In recent months, hackers stole the passwords of 3 million Adobe customers, 2 million Vodafone customers in Germany, and 160 million Visa credit and debit card customers. Others reside on your computer, which make them less vulnerable to external attack (although still not 100% secure), yet more vulnerable if your computer is stolen. The best of the programs generate passwords that are fiendishly hard to guess, and then store them in an encrypted file so that even if someone gets their hands on your computer, they can’t crack your passwords. All you have to remember is the one password to unlock the password file—and that should ideally be an unholy mess of upper- and lowercase letters, numbers, and special symbols, something like Qk8$#@iP{%mA. Writing down passwords on a piece of paper or in a notebook is not recommended because that is the first place thieves will look.

One option is to keep passwords stored on your computer in an encrypted password management program that will recognize the websites you visit and will automatically log you in; others will simply allow you to retrieve your password if you forget it. A low-cost alternative is simply to save all your passwords in an Excel or Word file and password-protect that file (make sure to choose a password that you won’t forget, and that isn’t the same as other passwords you’re using).

Don’t even think about using your dog’s name or your birthday as a password, or, for that matter, any word that can be found in a dictionary. These are too easy to hack. A system that optimizes both security and ease of use is to generate passwords according to a formula that you memorize, and then write down on a piece of paper or in an encrypted file only those websites that require an alteration of that basic formula. A clever formula for generating passwords is to think of a sentence you’ll remember, and then use the first letters of each word of the sentence. You can customize the password for the vendor or website. For example, your sentence might be “My favorite TV show is Breaking Bad.”

Turning that into an actual password, taking the first letter of each word, would yield

M f T V s i B B

Now replace one of those letters with a special symbol, and add a number in the middle, just to make it particularly safe:

M f T V $ 6 i B B

You now have a secure password, but you don’t want to use the same password for every account. You can customize the password by adding on to the beginning or the end the name of the vendor or website you’re accessing. If you were using this for your Citibank checking account, you might take the three letters C c a and start your password with them to yield

C c a M f T V $ 6 i B B

For your United Airlines Mileage Plus account, the password would be

U A M P M f T V $ 6 i B B

If you encounter a website that won’t allow special characters, you simply remove them. The password for your Aetna health care account might then be

A M f T V i B B

Then, all you have to write down on a piece of paper are the deviations from the standard formula. Because you haven’t written down the actual formula, you’ve added an extra layer of security in case someone discovers your list. Your list might look something like this:

|

Aetna health insurance |

std formula w/o special char or number |

|

Citibank checking |

std formula |

|

Citibank Visa card |

std formula w/o number |

|

Liberty Mutual home insurance |

std formula w/o spec char |

|

Municipal water bill |

std formula |

|

Electric utility |

first six digits of std formula |

|

Sears credit card |

std formula + month |

Some websites require that you change your password every month. Just add the month to the end of your password. Suppose it was your Sears credit card. For October and November, your passwords might be:

S M f T V $ 6 i B B Oct

S M f T V $ 6 i B B Nov

If all this seems like a lot of trouble, IBM predicts that by 2016, we’ll no longer need passwords because we’ll be using biometric markers such as an iris scan (currently being used by border control agencies in the United States, Canada, and other countries), fingerprint, or voice recognition, yet many consumers will resist sharing biometrics out of privacy concerns. So maybe passwords are here to stay, at least for a little while longer. The point is that even with something as intentionally unorganizable as passwords, you can actually, quite easily become mentally organized.

Home Is Where I Want to Be

Losing certain objects causes a great deal more inconvenience or stress than losing others. If you lose your Bic pen, or forget that crumpled-up dollar bill in your pants when you send it to the laundry, it’s not a calamity. But locking yourself out of your house in the middle of the night during a snowstorm, not being able to find your car keys in an emergency, or losing your passport or cell phone can be debilitating.

We are especially vulnerable to losing things when we travel. Part of the reason is that we’re outside of our regular routine and familiar environment, so the affordances we have in place at home are not there. There is added demand on our hippocampal place memory system as we try to absorb a new physical environment. In addition, losing things in the information age can pose certain paradoxes or catch-22s. If you lose your credit card, what number do you call to report it? It’s not that easy because the number was written on the back of the card. And most credit card call centers ask you to key in your card number, something that you can’t do if you don’t have the card right in front of you (unless you’ve memorized that sixteen-digit number plus the three-digit secret card verification code on the back). If you lose your wallet or purse, it can be difficult to obtain any cash because you no longer have ID. Some people worry about this much more than others. If you’re among the millions of people who do lose things, organizing fail-safes or backups might clear your mind of this stress.

Daniel Kahneman recommends taking a proactive approach: Think of the ways you could lose things and try to set up blocks to prevent them. Then, set up fail-safes, which include things like:

- Hiding a spare house key in the garden or at a neighbor’s house

- Keeping a spare car key in your top desk drawer

- Using your cell phone camera to take a close-up picture of your passport, driver’s license, and health insurance card, and both sides of your credit card(s)

- Carrying with you a USB key with all your medical records on it

- When traveling, keeping one form of ID and at least some cash or one credit card in a pocket, or somewhere separate from your wallet and other cards, so that if you lose one, you don’t lose everything

- Carrying an envelope for travel receipts when you’re out of town so that they’re all in one place, and not mixed in with other receipts.

And what to do when things do get lost? Steve Wynn is the CEO of the Fortune 500 company that bears his name, Wynn Resorts. The designer of the award-winning luxury hotels the Bellagio, Wynn, and Encore in Las Vegas, and the Wynn and Palace in Macau, he oversees an operation with more than 20,000 employees. He details a systematic approach.

Of course, like anyone else, I lose my keys or my wallet or passport. When that happens, I try to go back to one truth. Where am I sure that I saw my passport last? I had it upstairs when I was on the phone. Then I creep through the activities since then. I was on the phone upstairs. Is the phone still there? No, I brought the phone downstairs. What did I do when I was downstairs? While I was talking I fiddled with the TV. To do that I needed to have the remote. OK, where is the remote? Is my passport with it? No, it’s not there. Oh! I got myself a glass of water from the fridge. There it is, the passport is next to the fridge—I set it down while I was on the phone and not thinking.

Then there is the whole process of trying to remember something. I have the name of that actor on the tip of my tongue. I know that I know it, I just can’t get it. And so I think about it systematically. I remember that it began with a “D.” So let’s see,  , day, deh, dee, dih, die, dah, doe, due, duh, dir, dar, daw . . . I think hard like I’m trying to lift a weight, going through each combination until it comes.

, day, deh, dee, dih, die, dah, doe, due, duh, dir, dar, daw . . . I think hard like I’m trying to lift a weight, going through each combination until it comes.

Many people over the age of sixty fear that they’re suffering memory deficits, fighting off early-onset Alzheimer’s, or simply losing their marbles because they can’t remember something as simple as whether they took that multivitamin at breakfast or not. But—neuroscience to the rescue—it is probably just that the act of taking the pill has become so commonplace that it is forgotten almost immediately afterward. Children don’t usually forget when they’ve taken pills because the act of pill taking is still novel to them. They focus intently on the experience, worry about choking or ending up with a bad taste in their mouths, and all these things serve two purposes: First, they reinforce the novelty of the event at the moment of the pill taking, and second, they cause the child to focus intently on that moment. As we saw earlier, attention is a very effective way of entering something into memory.

But think about what we adults do when taking a pill, an act so commonplace that we can do it without thinking (and often do). We put the pill in our mouths, take a drink, swallow, all while thinking about six other things: Did I remember to pay the electric bill? What new work will my boss give me to do today at that ten o’clock meeting? I’m getting tired of this breakfast cereal, I have to remember to buy a different one next time I’m at the store. . . . All of this cross talk in our overactive brains, combined with the lack of attention to the moment of taking the pill, increases the probability that we’ll forget it a few short minutes later. The childlike sense of wonder that we had as children, the sense that there is adventure in each activity, is partly what gave us such strong memories when we were young—it’s not that we’re slipping into dementia.

This suggests two strategies for remembering routine activities. One is to try to reclaim that sense of newness in everything we do. Easier said than done of course. But if we can acquire a Zen-like mental clarity and pay attention to what we’re doing, letting go of thoughts of the future and past, we will remember each moment because each moment will be special. My saxophone teacher and friend Larry Honda, head of the Music Department at Fresno City College and leader of the Larry Honda Quartet, gave me this remarkable gift when I was only twenty-one years old. It was the middle of summer, and I was living in Fresno, California. He came over to my house to give me my weekly saxophone lesson. My girlfriend, Vicki, had just harvested another basket of strawberries, which were particularly plentiful that year, from our garden, and as Larry came up the walkway, she offered him some. When other friends had come by and Vicki had offered them strawberries, they ate them while continuing to talk about whatever they were talking about before the appearance of the berries, their minds and bodies trying to eat and talk at the same time. This is hardly unusual in modern Western society.

But Larry had his way of doing things. He stopped and looked at them. He picked one up and stroked the leafy stem with his fingers. He closed his eyes and took in a deep breath, with the strawberry just under his nostrils. He tasted it and ate it slowly with all his focus. He was so far into the unfolding of the moment, it drew me in, too, and I remember it clearly thirty-five years later. Larry approached music the same way, which I think made him a great saxophone player.

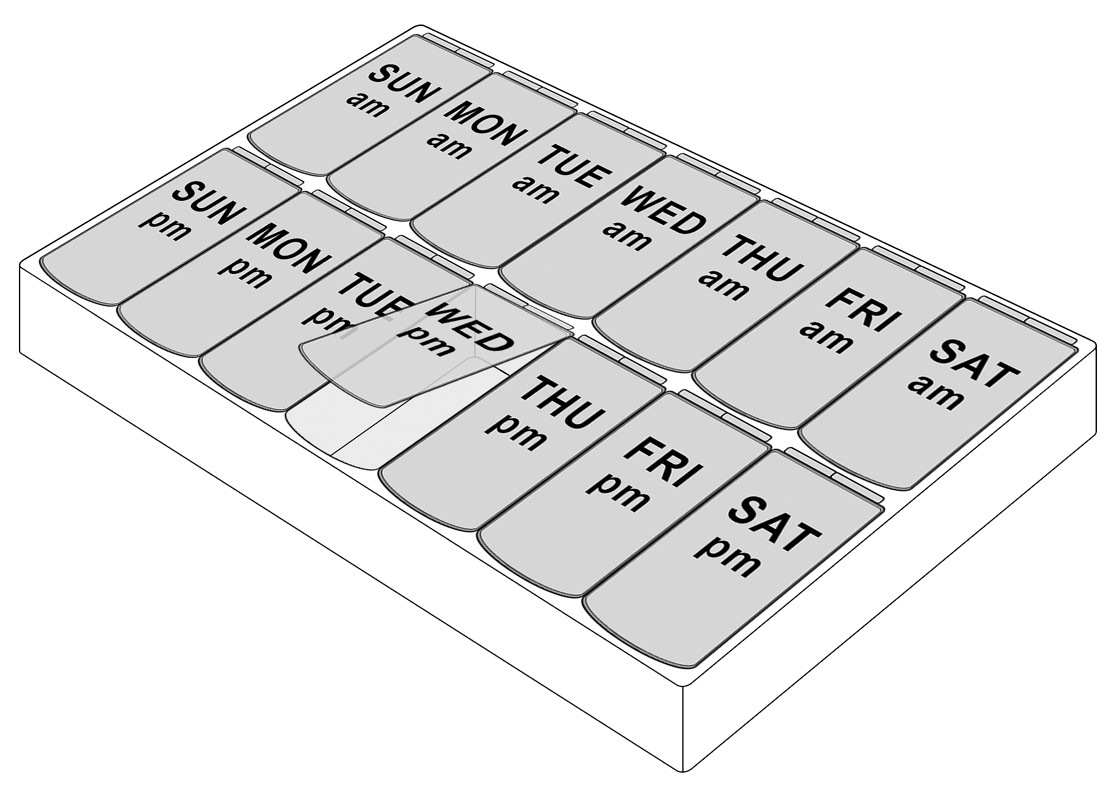

The second, more mundane way to remember these little moments is much less romantic, and perhaps less spiritually satisfying, but no less effective (you’ve heard it before): Off-load the memory functions into the physical world rather than into your crowded mental world. In other words, write it down on a piece of paper, or if you prefer, get a system. By now, most of us have seen little plastic pill holders with the names of the days of the week written on them, or the times of day, or both. You load up your pills in the proper compartment, and then you don’t have to remember anything at all except that an empty compartment confirms you took your dose. Such pillboxes aren’t foolproof (as the old saying goes, “Nothing is foolproof because fools are ingenious”), but they reduce errors by unloading mundane, repetitive information from the frontal lobes into the external environment.

—