In the autumn of 1923, as the second season at the tomb was about to get underway, the Metropolitan Museum’s Bulletin published a report by Arthur Mace of the Egyptian Expedition, whose steady hand – and brain – made such a significant contribution to the removal, recording and repair of the Tutankhamun objects in the first two years of work. Mace offered readers of the Bulletin a look back at the momentous events of the first season, and the Museum’s key role in them – especially for the photography that was so fundamental to the undertaking. As Mace explained,

Photography was the first and most pressing need at the outset, for it was absolutely essential that a complete photographic record of the objects in the tomb should be made before anything was touched. This part of the work was undertaken by Burton, and the wonderful results he achieved are known to every one, his photographs having appeared in most of the illustrated papers throughout the world. They were all taken by electric light, wires having been laid to connect the tomb with the main lighting system of the Valley, and for a darkroom, appropriately enough, he had the unfinished tomb which Tutankhamun had used as a cache for the funerary remains of the Tell el Amarna royalties.1

How straightforward the role of photography seems in Mace’s explanation, which appeared almost verbatim in the first volume of The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen that he and Carter co-authored (‘Obviously, our first and greatest need was photography’).2 The idea of a photographic record had long been gospel in archaeology.3 As with many other disciplines and field sciences, it is difficult to imagine that archaeology would have taken the form it did in the late nineteenth century without the existence of photography, and it is no coincidence that archaeological projects, publications and university appointments markedly increased from the 1890s onwards, when both photography and the reproduction of photographs in print became easier and cheaper. Photography also encouraged – and endorsed – a way of seeing and being an archaeologist that had become the field’s scientific standard by the 1920s, and that remains largely unchallenged in its methods and epistemology. Expert, trained eyes were needed first to recognize what an archaeological feature or object was, then to photograph it appropriately, and later to use the photograph as external reinforcement of an internal, visual memory.4

The technical details of Mace’s Bulletin report, elaborated further in his and Carter’s book, validate the work of photography and the excavation alike. The two are inextricable down to the repurposing of tomb KV55 – the ‘unfinished tomb’ – as Burton’s on-site darkroom, a reuse that resonates across millennia to link ever more closely the historical personage of Tutankhamun and the contemporary archaeologists. The Valley of the Kings was a space for serious undertakings, whether in the ancient Egyptian New Kingdom or the 1920s. As a core part of their undertaking, photography was uppermost in the excavators’ minds, but the photographic record that Burton produced attests that its creation remained a work-in-progress. Those ‘wonderful results’ were achieved through experimentation, adjustment, and a degree of serendipity, while the planned destination – or destinations – of the ‘record’ negatives and prints shifted with the progress of the work as well. There were many more, and more kinds, of photographs taken during the excavation than the in situ photographs that Mace emphasized after the first season, with their seeming glimpse of the tomb frozen in Tutankhamun’s time. Practical considerations also went far beyond the supply of electricity and the availability of a darkroom for quick development and test printing. Photography influenced the entire schedule of the work, depending not only on Burton’s availability (an issue in later years, in particular) and lighting conditions, but also on the progress of unpacking, stabilizing, cataloguing, cleaning and crating the thousands of objects discovered. If objects were going to be photographed (not all of them were), only once this was done were they readied for transport to Cairo, an end-of-season deadline that determined the point by which Burton’s photographic work had to be finished. Not surprisingly, questions surrounding the supply, shipment, and aftercare of the negatives and prints preoccupied everyone involved, and although Mace, Carter and Burton all emphasized the thoroughness of the photographic programme, the photographic archive presents numerous gaps and oversights, with as many missed chances as there are iconic images of iconic objects, tomb views and Egyptologists. Negatives were lost or damaged, tempers flared, and Burton at times struggled to satisfy both Carter and the Museum, not to mention himself.

This chapter surveys the role of photography throughout the ten-year project of clearing and documenting the tomb of Tutankhamun. Arrangements for Burton’s work were paramount, as Mace acknowledged, but they were also contingent on other factors. Closer scrutiny of how different photographic practices were embedded in different spheres of activity counters the narrative of discovery, neutrality and scientific rigour that dominated the official presentation of the find – as well as the focus on the first two seasons that has dominated most previous discussions of the excavations. The first section of the chapter looks at how implicit ideas about the visual qualities and purposes of photographs contributed to Harry Burton being brought on board in 1922. The chapter then turns to the initial arrangements made for documenting and photographing the tomb and its objects, which intersects with the archival history discussed in Chapter 2. Finally, the chapter considers changes in photography at the tomb from the time work resumed in 1925 until Burton took his last shots in the Burial Chamber in January 1933. From technical issues, such as lighting and the use of colour plates or moving-picture cameras, to questions of patronage, press obligations and time pressure, the practice of photography on site manifested many concerns that may seem distinctive to the tomb of Tutankhamun. But the excavation in fact was similar to contemporaneous archaeological projects in terms of the empirical aims and archaeological authority that photography helped articulate and, indeed, create. In Egypt and elsewhere, cameras gave archaeology a methodological framework and an aesthetic identity in two ways: first through the performance of photography, that is, how one ‘did’ or took the photograph, and second through the performance of the archive, that is, what one did with the photographic negatives and positives. It was this double indemnity that made photography ‘obviously’ a requirement in the field, as Mace and Carter wrote – and obviously worth getting right.

Faced with the first sealed doorway at the bottom of the now-famous steps, Carter knew that the seals themselves, bearing the name of a little-known king, were important even if nothing else survived. The mere existence of a tomb (if that is what it proved to be) would count as a major Egyptological discovery. At that point, Carter had no idea what exactly lay behind: what size or layout the structure would have, what it would contain, or what condition any contents would be in. It is from this moment of uncertainty we begin, for the camera enters the Tutankhamun story as a foray, a test of whether the archaeologist and the lens could be made to see the same thing.

They could not. Having waited for Carnarvon and his daughter Evelyn to arrive, on 24 November 1922, Carter and his friend Callender oversaw the re-clearance of the staircase to reveal the sealed doorway in its entirety. Rex Engelbach, the chief inspector of antiquities for Upper Egypt, came to observe in his official capacity, together with other colleagues including fellow Briton, the archaeologist Guy Brunton. Carter’s journal and his pocket diary diverge here, as the more descriptive prose of the journal slips between recording the day’s events and projecting into the future.5 The journal entry for 24 November elides the clearance of the stairwell, which yielded a mix of potsherds, broken boxes and a scarab naming several 18th Dynasty rulers, with a backwards glance at the hypothesis Carter first formed: this ‘conflicting data led us for a time to believe that we were about to open a royal cache’, rather than a single tomb.6 Worried about security, Carter spent the night camping near the tomb. The next day, he continued to make handwritten notes of the seal impressions and perhaps executed the sketches of impressed cartouches and their placement, now filed with the record cards for object number 4 in the catalogue of tomb objects.7 Supplementing these manual forms of recording, Carter also trained his own quarter-plate camera on the sealed doorway either that day or (if one prefers the pocket diary) the day before: ‘Made photographic records, which were not, as they afterwards proved, very successful’, as his journal tersely puts it.8

What makes a photograph a failure? Figure 3.1 gives us some idea of why Carter was dissatisfied with the results of his photographic efforts. Shadows at the top of the image, and a streak perhaps from a flaw in the chemical coating, obscure the rough plaster or bedrock – which one, is even difficult to tell. Over the surface of the doorway, a mottled pattern of light and shade overlays the impressions, a visual echo of the undulating texture of the plaster and the gritty rubble still remaining at the bottom of the doorway. The photograph almost resembles a stratigraphic section, with its horizontal bands of different heights (shadowy surface at top, wide band of impressions, gritty rubble below), but this was not the image Carter wanted or needed. To capture the impressed seals in sharp outline and be able to read the hieroglyphic signs within them – that was the goal. One appeal of photography for scientific purposes was that it allowed different viewers, in different places, to make a study of what the photograph represented, something that Carter, who had a rather basic command of ancient Egyptian, would have valued in interpreting the seals.9 But the sealed doorway presented several photographic challenges. Its subterranean position made it difficult to light consistently, and the plaster surface was rough, with impressions applied at different angles and depths, not to mention overlapping each other. The photograph Carter produced is a failure for the purpose of reading the seal impressions from it. That it succeeds as a photograph of the rather messy, daunting doorway the excavators faced, and as a testament to trial and error in the field, and flaws and fingerprints on negatives, matters only in retrospect. It did not matter to Carter in late November 1922, with the world’s press and his colleagues already attuned to the potential discovery of a royal tomb.

Figure 3.1 Seal impressions covering the first doorway of the tomb. Photograph by Howard Carter, 25 November 1922; GI neg. P0274, glass 8 × 10.5 cm.

Without knowing whether his exposures were ‘successful’, Carter, Callender and the unnamed (indeed, unmentioned) Egyptian workmen set to work removing the seal-stamped plaster, breaking it into moveable chunks that preserved as much as possible of the seals. They proceeded through the rubble-filled passageway, 9 metres long, to the second blocked doorway – the one famously pierced for one person at a time to peer through by candlelight, causing Carter to gasp, ‘Yes, it is wonderful’ (as the journal has it), or ‘Yes, wonderful things’ (as it became in his book with Mace). No one bothered to try to photograph the second doorway in the darkness of the passageway, and even the notes taken of the impressions on its surface were – by Carter’s own admission – ‘not sufficiently complete to give a detailed enumeration of the seals employed’, which he blamed on ‘the heat of excitement at the moment of the discovery’.10

In the flurry of the next week’s activity, the Antiquities Service enabled Callender to rig the Antechamber with electric lighting, to facilitate the initial inspection of the tomb by Service officials as well as Carter, Callender and the Carnarvons. Even this was not enough for photography, however, and attempts to take pictures using flash – perhaps by Carnarvon himself – also proved unsatisfactory, as Carnarvon explained to The Times when he was back in England. It was, he said, ‘impossible to distinguish between the ebony statues of king Tutankhamun and the dark shadows that were cast on the wall. The plates were useless’.11 There were plenty of other things to organize, however. An ‘opening’ ceremony took place on 29 November, attended by Lady Allenby (wife of the British high commissioner), the London Times correspondent Arthur Merton and his wife (a sign of the paper’s early advantage), and a number of Egyptian officials including the mudir of Qena province, the mamur markaz of Luxor, the head of police and the provincial irrigation inspector. Pierre Lacau and Paul Tottenham, from the Ministry of Public Works, came the next day. After these formalities were out of the way, and having consulted Lacau and Tottenham to make plans for the work, Carter had the tomb backfilled until a better security gate could be installed. To order the gate and other equipment (stationery, cardboard boxes and packing materials), Carter travelled to Cairo in early December with the Carnarvons.12 There, with preparations for the work foremost in his mind, he received a congratulatory telegram from Albert Lythgoe of the Metropolitan Museum, who was then in London on business. Carter replied with thanks, adding ‘discovery colossal and need every assistance, could you consider loan of Burton in recording in time being, costs to us, immediate reply would oblige’. Lythgoe did oblige, replying ‘only too delighted to assist in every possible way, please call upon Burton and any other members of our staff, am cabling Burton to that effect’.13

The exchange of telegrams between Lythgoe and Carter is the source of the gentleman’s agreement that would be remembered and revisited at various junctures not only over the course of the ten-year excavation, but over the following decades, as we have seen. Burton was not a passive participant in the transaction that linked him to Tutankhamun: in Cairo that December, Carter and Carnarvon had already sounded him out about his willingness to help with photography, before cabling the request to Lythgoe – wisely letting the decision appear to be up to the Metropolitan Museum.14 Lythgoe’s readiness to lend the Museum’s Egypt-based staff (including Mace, Hauser and Hall) was the result of long professional acquaintance, but it was also an offer made with the Museum’s own benefit in mind, for all that Egyptologists have preferred to emphasize Lythgoe’s scientific ‘disinterestedness’.15 The Museum stood to gain on several counts: publicity, fund-raising revenue, and, under the partage system, a potential share of the unparalleled finds, if descriptions (not yet photographs) of the Antechamber were anything to judge by. Assertions of scientific neutrality have nonetheless held fast in standard histories of the Tutankhamun excavation – with that supposed neutrality permeating every aspect of the archive, including Burton’s photography.

Although I touched briefly on Burton’s biography in Chapter 1, it is worth saying a bit more here about the skills and reputation he brought to the Tutankhamun ‘team’ in 1922 – and about the ways in which his role and his work have latterly been understood in Egyptological literature. Writers have been keen to analyze Burton’s photographic methods and emphasize his technical accomplishments, creating the impression that Burton’s was the decisive vision in terms of what to photograph, when, and how – the photographer as artist-auteur.16 This was not the case, whether in his work for the Metropolitan Museum, for the Tutankhamun excavation or in Italy, where he had been photographing Renaissance art and architecture since moving to Florence as secretary-companion of the English art historian Robert Cust in the 1890s. In addition to photographs he took for Cust in the early 1900s, Burton may also have accepted commissions to photograph artworks, especially paintings, for other expats; he seems to have maintained an interest in Renaissance art throughout his life.17 From the time he began travelling with, then working for, Theodore Davis in Egypt, however, archaeology was the focus of Burton’s activity: he was employed as an archaeologist, not as a photographer, however much photography became his remit once he began working for the Metropolitan’s Egyptian Expedition in 1914. Especially in the early years of his Museum employ, decisions about what to photograph emerged through networked dialogue, and Burton took photographs as favours and for exchange. That December in 1922, for instance, he had been in Cairo for a month, in part to take pictures of a statue in the antiquities museum as a courtesy – at Lythgoe’s request – for Museum trustee Charles W. Gould. Burton managed the task, but reported to Lythgoe that it had been a hassle, because Museum staff had to remove the case that covered the statue. Nonetheless, Burton took six negatives and posted two prints of each to Lansing – one for the Egyptian department, one for Gould.18

In other words, Burton’s evident skill with a camera might have been discussed and admired by his colleagues as a recording device, but it served other purposes as well, cementing professional and patronage relationships through photographic exchange. From his years with Cust, then Davis, Burton was accustomed to relying on social superiors for opportunities of advancement. But the subordinate tone he adopted in his correspondence with Lythgoe, especially early on in his employment, also reflects Burton’s awareness that he was a novice where Egyptology was concerned, unable to read hieroglyphs like his new colleagues did and uncertain what to prioritize when faced with requests to photograph a certain object, tomb, or site. For instance, tasked with photographing Egyptian collections in Florence and Turin in 1914, when the outbreak of war meant he could not get to Egypt, Burton sought advice from both Lythgoe and Mace about exactly what he should photograph, and with what size plate. Mace specified inscribed material as most important, and Lythgoe’s reply similarly revealed a set of disciplinary and museological priorities:

We wouldn’t need photographs of ushabtis, scarabs, amulets or similar small objects, but would like all kinds of sculpture (in the round or in relief), stelae and all the more important classes of material. The Turin collection, of course, contains the most important Egyptian material.19

Once Burton set out for Egypt to commence his work for the Expedition in 1915, Lythgoe was again specific, sending Burton a list of requirements that took into account site documentation as well as photographs needed for the Museum’s active publication programme.20 Not only what subject matter to photograph but how to photograph it were a normal part of the conversations Burton had with his colleagues, judging by his correspondence. Burton was the specialist when it came to photography, but all the archaeologists involved – just like Carter – were familiar with the technical considerations photography required: lighting conditions, the effect of temperature on negatives and developing solution, the use of filters and f-stops on a lens, not to mention the use of different lenses in different contexts. Like archaeology itself, photography was a joint enterprise – including the Egyptian assistants who worked with Burton, whom he referred to collectively as ‘camera boys’ in the derogatory language of the day.21

By 1922, after seven years of work with the Expedition, Burton’s colleagues fully recognized his distinctive skill with a camera, to the extent that he received publication credit when his photographs appeared in Museum publications or the illustrated press.22 The tributes paid to him years later, after his death in Egypt in 1940 from complications of diabetes, described his ‘expert knowledge of photography’ as ‘invaluable’ to the work of the Egyptian Expedition. In an obituary in the Metropolitan Museum Bulletin, Ambrose Lansing singled out another talent that stood Burton in good stead: ‘his cheerful disposition even under the most trying of circumstances endeared him to all with whom he came in contact’.23 Burton would need all his skill and good cheer to make a success of the photography of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

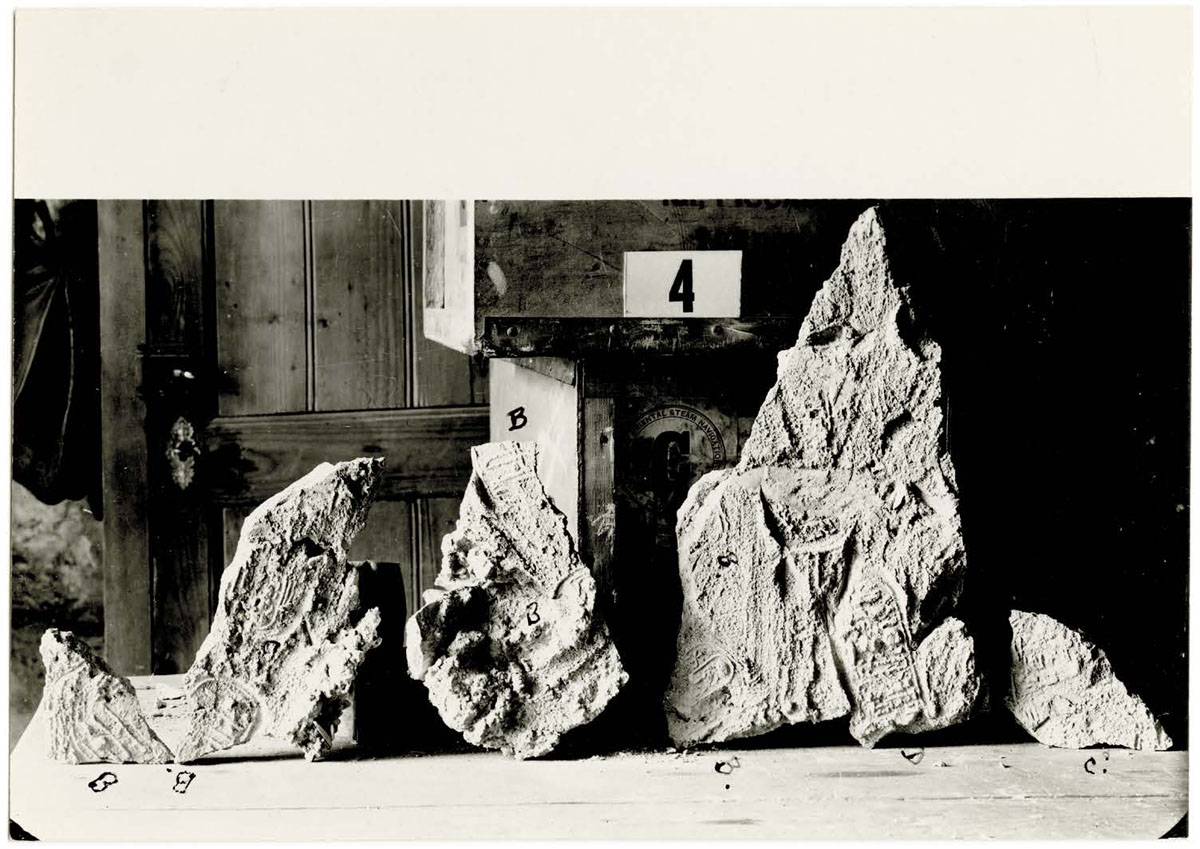

What such photographic success might look like began to emerge later in December 1922, when the team assembled in the Valley of the Kings to size up the work. On 18 December, the leading American Egyptologist James Breasted – then on a Nile journey with his family – arrived to view the tomb and offered his initial opinion on the still-sealed doorway to the Burial Chamber as well as the impressions on the chunks of plasterwork Carter had already removed from the first and second doorways.24 It may have been around this time that Burton ventured his own photographs of the fragmented sealings, before they were removed for storage; their whereabouts since his photographs were taken is unknown (Figure 3.2).

Even the setting of the photograph is uncertain: in the first weeks, nearby tomb KV4 offered storage space, but this is more likely the area just inside or outside the laboratory, tomb KV15, at the far end of the valley. If so, it supports a December 1922 date for the photographs, since the chunks of mud plaster needed to be out of the way before more attractive and delicate objects began to be removed from the tomb in the new year. Since their dismantling, these doorway fragments had been transformed from an in situ, sealed-up doorway, smoothed and stamped by many hands, into discrete, if unwieldy, objects that could be numbered and manipulated. The individual pieces of the first doorway were now collectively known as object 4, and as such could be turned into a photographic record. In Figure 3.2, we see one of the largest pieces of object 4 positioned on a table. It sits level and upright, a number card – presumably part of Carter’s stationery order in Cairo – positioned to the left and a wooden cabinet behind providing a neutral-enough background that no separate backdrop was deemed necessary. Light comes from the viewer’s left, and at least one of Burton’s Egyptian assistants will have been holding a reflector to concentrate and direct sunlight across the surface of the plaster. This raking light was what had been missing from Carter’s own attempt at photographing the seals in place: it was the only way to isolate the impressions and individual signs from the textured plaster surface. Directed light meant that object 4 could be ‘read’ from the photograph, its seals and their layering deciphered, or at least made to support a decipherment that would in fact require close in-person scrutiny, sketching and note-taking. The competing stamps and smears needed to make linguistic and logical sense – but they also needed to make photographic sense, producing a legible record that the trained eyes of Egyptologists could read or, failing that, take on trust.

Figure 3.2 The seal impressions from the first doorway of the tomb, now catalogued as object 4. Photograph by Harry Burton, on or around 18 December 1922; GI neg. P0277, glass 12 × 16 cm.

The visual epistemology of archaeology valued clarity of detail, especially where inscriptions were concerned: Breasted himself was in the process of establishing an Epigraphic Survey of the great temples at Luxor, using photography as an intermediate stage in producing exacting scale drawings of inscriptions and relief on the temple walls.25 A photograph was one step in a process that extended before and beyond the exposure of a negative or the making of a print. After all, for readers of Arabic numerals the card printed with a bold number 4 is the most legible text in Burton’s photograph, and any eventual publication of the seals would likely have transformed the hieroglyphs into a facsimile drawing and typeset transcription.

From the moment Carter admitted the failure of his own attempts, the process of photography was thus built into every aspect of the Tutankhamun excavation, from the choice of camera and negative (Burton’s photographs of the seals are, less usually for him, on glass half-plates), to the timing of the clearance and recording work, to the arrangements for printing, distributing and filing the results. Photography would help bring the apparent jumble of Tutankhamun’s tomb into manageable order, creating usable data out of the abundant detritus of ancient ritual – or at least, as the next section demonstrates, that was the plan.

Since the 1970s, accounts of the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun have reiterated the methodical organization of the removal and recording work, emphasizing its meticulous detail and objective accuracy in echoes of Carter’s own words. Several point out that Carter removed the first doorway only after it had been photographed, without mentioning that he considered the photographs a failure and did not photograph the second doorway, at the entrance to the Antechamber.26 With his team assembled, and probably in consultation with them, Carter developed a scheme of organization – an ideal, which worked in some respects but not in others; scale drawings were only ever made of the Antechamber, for example. To conflate the scheme’s intentions with its execution is to overlook the contexts and contingencies through which scientific knowledge is generated: that is the point here, not whether the excavation was as ‘methodical’ as Egyptology has asserted.27 Historians of science have moved away from, and critiqued, the hagiographic approach of earlier historians, but the history of archaeology and Egyptology continues to be dominated by biographies and surveys with little or no analysis, nor awareness of such historiographic considerations.28 Even work that purports to critique the history of Egyptology from within (such as recent publications identifying the Nazi party affiliations of German and Austrian Egyptologists) implies, as William Carruthers observes,

that these practices can, after appropriate historical reflection, be separated from pernicious political “ideology”. In this way, influences inappropriate to the conduct of scholarly inquiry can be placed outside the Egyptological sphere and the discipline progress to better, implicitly more correct, work. In this sense, then, constituting disciplinary history is akin to a practice of purification: a means of claiming future Egyptological work as authoritative by suggesting that it can be removed from negative influences and instead take on an ideal form.29

Instead, ‘the act of constructing a pure discipline, no matter how unintentionally, allows practitioners attached to that discipline to assert their place within the world: by purging order, order is also produced’ – an order, I would add, that often looks to excavation archives and photographic ‘records’ to make ahistorical judgements about accuracy, objectivity, and veracity.30

In this section, I use Burton’s photography during the first two seasons at the tomb to consider the practical considerations of his work as well as the visual and verbal emphasis placed on it in contemporary publications. Those first two seasons, before Carter’s conflict with the Antiquities Service became public knowledge in February 1924, have been taken as representative of the entire excavation project, but using the rhythm and rhetoric of photography at the site helps bring that into perspective. I look first at Burton’s overall output for the tomb of Tutankhamun, building on the archival histories discussed in the preceding chapter. I then consider how Carter, Mace and Burton discussed photography in the press and in the first book on the tomb, a bestseller when it was published in 1923. The photographic archive and surviving tomb registers intersect with their statements in variously competing or complementary ways. The section concludes by considering how Burton brought different photographic techniques to bear on his work in ways that speak to aims beyond those that the archaeologists articulated – and in ways that would gradually be reconfigured when work resumed in 1925, as the final section of the chapter will discuss.

The half-plate photograph of object 4 is one of five extant negatives depicting that object number: three show other parts of the demolished doorway, propped on the same table (often with cigarette boxes and Fortnum and Mason packing cases as support), and two show the same section as in Figure 3.2, ‘duplicates’ now divided between Oxford and New York.31 We saw in Chapter 2 that confusions arising from different practices of duplication and copying led both the Griffith Institute and the Metropolitan Museum of Art to think of themselves as having a complete and essentially identical set of photographic negatives and positives. At the same time, the priority archaeology has given to a photograph’s subject matter – the looking through, not at, the photograph – has meant there was little motivation for tallying the total number of photographs taken at the tomb, at different phases of the work and in different formats.32

Such information would normally have been part of a photographer’s log book or register, like the register the Metropolitan Museum dig-house kept of its share of the Tutankhamun photographs and of Burton’s normal output for the Egyptian Expedition. Other excavations kept even more detailed logs, such as those George Reisner described for his work at Giza: the 40 × 44 cm photo registers (similar to the site’s object registers) had columns for recording the negative serial number, brief description, place taken, photographer, date, plate size and other remarks.33 Individual methods of tracking photographs on site were diverse, but also widespread; photography was too important, and its products so numerous, that some means of keeping track was required. No wonder that when Lansing and Harden began to compare their respective Tutankhamun holdings in the late 1940s, the men assumed that a catalogue of the Tutankhamun photographs existed. It did not. The parallel ‘red’ and ‘black’ lists that Carter made of the developed negatives seem to have done no more than equate negative and object numbers (or other subjects), while Burton himself apparently kept no separate log – and in any case, no complete list of the black numbers, a correlation between the two sets, or a photographer’s log survives.

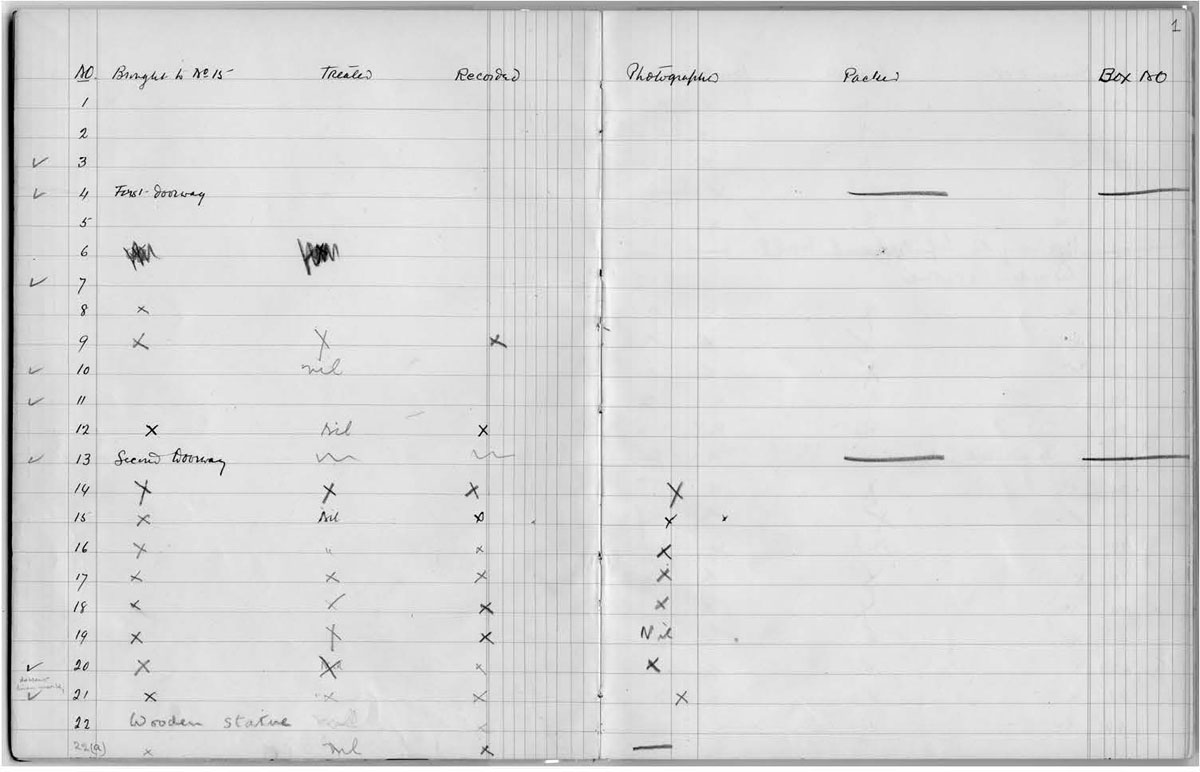

What does survive in the Griffith Institute – overlooked in other studies of the excavation – is a slim, twenty-five-page bookkeeping notebook pressed into service as a working log in the first season, the winter of 1922–3, and converted to a list of running object numbers after that (Figure 3.3). The handwriting throughout is Carter’s, but a system of crosses used in the first ten page-spreads devoted to 1922–3 might have been done by others; they were certainly done at different times, judging by the mix of writing media. These page-spreads have columns for Brought to No. 15, Treated, Recorded, Photographed, Packed and finally Box No. [number], to indicate the boxes bound for Cairo. However, even the first page shows that the system was inconsistently applied: object 4 seems to have been ‘brought to no. 15’, but the other columns are blank until the thick pencil strokes under ‘packed’ and ‘box no.’, which imply that neither occurred. Other objects were ticked, by someone, as photographs were made or (perhaps) negatives catalogued, but not all objects seem to have required separate photography, or perhaps they missed their chance: object 19, eventually catalogued on index cards as five pieces of basketry or floral material, has the word ‘nil’ in the photography column (correctly: there are no photographs that isolate these objects, and the catalogue cards indicate that four of the five pieces were not kept once recorded).34 The frantic pace and pressure of the first two seasons is evident as the notebook becomes a pencilled list of object numbers and brief descriptions, punctuated by tick marks of uncertain meaning. Carter continued to use the notebook until the final object number – 620 – was assigned in 1928, but without trying to track the progress of recording and photography. Only an inserted slip of paper cross-refers to the unlocated register of negatives: ‘Note for Burton. A set of prints required for register nos. 1135 to 1150’.35

Figure 3.3 First page of the working register of objects for the tomb, showing numbers 1 to 22. Carter archive, Notebook 13.

The only way to reconstruct how many photographs Burton made, on what date, and in what format is to weave the photographic archive together with the rest of the excavation archive, in particular the diaries and journals kept by Carter and, for the first two seasons, Mace. Carter’s journals and diaries sometimes mention when Burton started and ended his work or, during the November 1925 mummy unwrapping, the specific times of day given over to photography. Which object was removed on which day, or repaired at a certain time, can suggest a date before or after which certain photographs were taken. Dated notes about phases of work within the tomb likewise indicate specific days or weeks when corresponding photographs must have been taken on site. Other sources of evidence offer clues as well: Burton’s correspondence with his Metropolitan Museum colleagues, the diary of his wife Minnie, and to some extent the dates when his photographs appeared in the press, which involved at least a two-week delay thanks to the time it took to post prints to London.36 Internal cues nonetheless leave question marks about when, even where, some of the photographs in the Tutankhamun archive were taken, or by whom. Some of these uncertainties originate in the first phase of the archive’s formation, while the excavation was in progress; others have been introduced during the subsequent archival orderings and re-orderings.

A bit of number-crunching from my own research in both collections offers a rough guide to the contents of the entire photographic archive and the season-by-season character of the work. Although it was impossible to see every negative (the large-format glass plates being especially restricted for handling), I was able to scan the shelves and drawers in both archives in order to check negative numbers, sizes and materials. My working database of the archive, which incorporates these observations, estimates that there are around 3,400 negatives, or prints from lost negatives, in both Oxford and New York – more in Oxford than in New York, since Carter retained his own small-format glass negatives and a number of negatives from handheld cameras, as well as almost all the Burton negatives that depicted himself, Mace, Callender or the Egyptian foremen at work. Of these 3,400, around 700 are copy negatives made since the 1950s, by photographing prints for which no negative survives or for which only one negative was ever made, both during and since the Scott and Fox collation. However, this has not led to all the original glass plates being printed, because where Burton did take two (or more) similar exposures, he and Carter only chose one negative to print. Hence the creation of copy negatives from existing prints has replicated the earlier printing choices, rather than reflecting the full range of negatives in either institution. Of the prints for which no negatives exist, the largest group comprises about seventy photographs that show parts of the outermost burial shrine (object 207) before it was re-erected at the Cairo Museum. The approximate total of 3,400 also includes more than a hundred known in the Griffith Institute as the ‘Valley of the Kings’ negatives, most taken by Burton, some by Carter. To these, Carter assigned Roman rather than Arabic numerals, to distinguish them from photographs taken of the tomb and tomb objects.37

Correlating the photo archive to events mentioned in diaries and correspondence allows some reconstruction of the schedule of the work, and in particular, a better understanding of how many photographs (that is, negative exposures) Burton took each season and how the intensity of photograph work across different seasons compares (Table 3.1). It is immediately obvious that in the first season, many more photographs were taken than in any subsequent year – some 750, nearly double the range of 400 to 450 in Seasons 2, 4, 5 and 6, and nearly a third more than the next most numerous season, Season 7, when Burton photographed objects from the Annexe, the last part of the tomb cleared. Season 1 also saw Burton use considerably more half-plate negatives than he did in other seasons: more than half of the approximately 750 for which he was responsible. In contrast, in every other season, nearly all the photographs Burton took were in his preferred 18 × 24 cm format. It may be that in Season 1 only smaller plates were available in the numbers needed for the unexpected discovery, either from existing stock that Carter or the Metropolitan Museum had to hand, or based on what could be bought locally in Luxor or ordered from Cairo.

The higher number of half-plates also reflects Burton’s use that season of a stand that held a camera upside-down over a sheet of ground glass, for photographing small objects.38 This camera had a fixed front (rather than swing-and-tilt) and took or could be adapted to take the half-plate size, judging by the resultant negatives in the archives. In later seasons, he used a different ground-glass stand, which accommodated his preferred full-plate camera for object photography.39 Overall, large-format plates outnumber half-plates in the archive by a ratio of 2:1, with more than 2,000 negatives (lost or extant) measuring 18 × 24 cm compared to around 1,100 half-plates. For the remaining 230 or so images in my working database, either no original negative (or indication of negative size) exists, or else they comprise a mix of film and glass negatives in smaller formats, ranging from quarter-plates (9 × 12 cm, 8.5 × 10.5 cm) to roll or sheet film from handheld cameras. Burton did, briefly, try large-format film sheets (eight of these survive in the Oxford archive), but he seems to have rejected them as unsuitable, whether because of the results they gave or other concerns.40 Similarly, Burton experimented with Autochrome colour plates both in his work for the Metropolitan Museum and at Tutankhamun’s tomb, as discussed below. The glitter of gold and stones, and shades of ebony and ivory, were a fundamental part of the marvel the Tutankhamun objects inspired, but photography could still do its work in black-and-white, yielding results as crisp and clear as the archaeologist’s self-avowed priorities where the scientific record of the tomb was deemed at stake.

Table 3.1 More than ten years of photography at the tomb of Tutankhamun, with estimates of how many photographic exposures Harry Burton took each season.

| Season and dates | Activities | Exposures |

| Season 1, October 1922 to May 1923 | Clearing the Antechamber, dismantling wall adjoining Burial Chamber, initial investigation (and photography) of Burial Chamber and Storeroom (or Store-Chamber, which Carter renamed the Treasury in late 1920s) | ca. 750 |

| Season 2, October 1923 to 9 February 1924 (Carter’s ‘strike’) | Clearing the Burial Chamber, disassembling the burial shrines, lifting the sarcophagus lid | ca. 400 |

| Season 3, January to March 1925 | Working on objects from Burial Chamber and Treasury, including vases 210 and 211, and fans 242 and 245; initial investigation and cleaning of outermost coffin | ca. 150 |

| Season 4, September 1925 to May 1926 | Opening the coffins and unwrapping the mummy; photography of mask and inner coffin (December 1925); spring spent working on objects removed from mummy | ca. 450 |

| Season 5, September 1926 to May 1927 | Re-photographing and clearing the Treasury; re-photographing Box 21; photography of objects such as the small shrines containing wrapped statuettes | ca. 450 |

| Season 6, October 1927 to April 1928 | Opening the canopic chest; photography of canopicjars and contents, foetal remains, boat models, and shabti-figures; clearing the Annex | ca. 400 |

| Season 7, September to December 1928 (according to Carter’s journal), continuing into spring 1929 (Burton’s correspondence) | Photography of objects from Annex, including calcite (alabaster) and ceramic vases, and Box 370 containing weapons. Burton suffered an attack of dengue fever in November, delaying his work. | ca. 600 |

| Season 8, winter of 1929–30 | Carter negotiating with Ministry of Public Works, to arrange financial settlement for Carnarvon family | No photography |

| Season 9, September to November 1930 | Work on the burial shrines and chair 351; opening of magical brick niches in Burial Chamber | ca. 50 |

| Seasons 10 and 11 (no Carter journal), during the winters of 1930–31 and 1931–1932 | Further work on the burial shrines, which were readied for shipment to the Cairo museum in 1932 | ca. 100 |

| Winter of 1932–33 | Photography of burial shrines in the Cairo museum, November or December 1932, and of the sarcophagus in place in the tomb’s Burial Chamber, January 1933 | ca. 50 |

Uncertainties over the date of certain photographs, and the existence of similar negatives with identical numbers, make it difficult to give an exact quantity of exposures, hence the estimates given here. These yield a total of 3,400 photographic exposures, not far off the 3,427 photographs I have documented in the New York and Oxford archives.

This phrase was the title of the penultimate chapter in Carter and Mace’s The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, written and published at speed in 1923.41 The chapter elucidates the methods used to record and repair the tomb objects, which, the authors emphasized, was an essential task of the archaeologist. Using a language of obligation and responsibility, and writing in Carter’s authorial voice, they present the systematic approach taken at the tomb – in which photography was essential:

Then there is photography. Every object of any archaeological value must be photographed before it is moved, and in many cases a series of exposures must be made to mark the various stages in the clearing. Many of these photographs will never be used, but you can never tell but that some question may arise, whereby a seemingly useless negative may become a record of the utmost value. Photography is absolutely essential on every side, and it is perhaps the most exacting of all the duties that an excavator has to face. On a particular piece of work I have taken and developed as many as fifty negatives in a single day.42

It was in fact Burton, not Carter, who took fifty negatives a day at the busiest times, as the season-by-season breakdown of his photographic output helps demonstrate (see Table 3.1). How that output fitted into – and shaped – the larger scheme of work on site is what concerns us here. No matter how specialist it became, photography could not be isolated from other activities in the tomb and in the so-called laboratory of KV15. Specialization required more, not less, coordination, and Carter and Mace described a ‘very definite order of procedure’ to keep the work flowing smoothly.43 Each ‘primary’ object was assigned a registration number while still in the tomb, but in many cases – notably the ancient boxes full of other material – letters of the English alphabet were used for associated objects, doubled, tripled, or (at the mummy unwrapping) quadrupled as required. Hence the painted box, object 21, eventually required sub-numbers from 21a to 21yy in order to separate and catalogue the various material it contained. ‘Constant care’ was required to keep the objects and their number and letter tickets together all the way through the process, since Burton needed these cards for his photographs as well.44

The recording system that Carter envisioned, and more or less maintained throughout the project, was based on the use of 6 × 8-inch (15 × 20 cm) index cards. The cataloguing was, by design, an endeavour of multiple hands and multiple media, and photography contributed to the hybrid forms the task required. The main card was to include basic data (object number, material, measurement) and a description, another card would include Lucas’s notes on any cleaning and repair undertaken, and inscribed material would have a separate card with Gardiner’s notes and translation. There should then be at least two photographs for each object: one showing its position in the tomb, followed by one or more ‘scale photographs’ (as Carter termed them) showing the object on its own.45 In the card catalogue, preserved in the Griffith Institute, several prints are often filed behind the written cards; prints from full-plate negatives had to be folded in half or cut down in order to fit. The prints interrelate with the catalogue cards and with drawings Carter made, either on squared paper or on the cards themselves; he also occasionally made a notation directly onto a print. The set of cards for object 4, the sealings of the first doorway, is one example of how drawings and an annotated photograph supplemented the main card, which in this case gives only the number and identification of the ‘object’. A fuller description was typed onto two pieces of foolscap paper, folded in half, and then filed with a trimmed and part-folded piece of squared paper on which Carter made rough sketches of the impressions. These pages are followed by four prints, one from each half-plate negative that showed a distinct section of the object – and each print has been inked with a letter corresponding to the typed description and indicating which seal impression is visible (Figure 3.4).

Other prints in the card catalogue bear traces of pencil lines, applied along a straight edge to mark where they were trimmed down; some have scale ratios (e.g. 1:4) pencilled on the back. Photographs may also have been a reference for Carter when he executed detailed drawings on the record cards of some objects, like the ‘throne’ (object 91), complementing in-person observation. The drawings and photographs of an object usually share the same orientation.

In this process, numbering was a significant act of transformation, and one which Burton’s photographs perpetuated so successfully that the Carter object numbers are still used (as I do here) in preference to the registration numbers eventually given to the objects in the Cairo Museum. Assigning numbers changed them from the material traces of ancient acts of manufacture and deposition, to objects for archaeological study, with the new acts of manipulation this status required. Carter must already have formed a plan to associate numbers with the in situ objects, since the printed number cards appear in Burton’s first photographs inside the tomb (see Figure 1.2); presumably the cards were among the stationery items ordered in Cairo in early December 1922. The idea of numbering the objects while they were in place, rather than after they had been removed, was an efficient solution to the distinctive situation the Antechamber presented, with its closely stacked objects and ‘crime scene’ disturbances. Numbering features on a site, and sequentially cataloguing objects, were both well-established in archaeological practice, although this is the first instance I know of where they were brought together in this way. Likewise, archaeologists had used different methods of incorporating the numbers of both site features and objects into the photographic record, either within the staging of the photograph (chalking a grave number on a slate, for instance) or by marking the negative after the fact. The number-card system was a solution to the distinct set of problems the archaeologists faced, especially in the Antechamber, but it was not a system others chose to adopt. At Giza, in contrast, George Reisner did not pre-number the jumbled funerary material of queen Hetepheres he found in 1926 inside a single chamber.46 His Egyptian staff photographer, Mohammedani Ibrahim, took copious photographs of the material in place, but numbers were assigned after, not before, removal.47

Figure 3.4 Print from GI neg. P0278 marked-up in Carter’s hand, from the card catalogue record for object 4 – the sealings from the first blocked doorway of the tomb.

At the tomb of Tutankhamun, the large type face on most of the number cards – which are around 2 inches (5 cm) tall, judging them against object measurements – made them clearly legible in the photographs, another indication of how photography was designed into other archaeological acts. The inclusion of the cards helped draw attention to items in the photographs that might not immediately have appeared to be separate or significant ‘objects’, except to the observers who were on the spot. For example, in one of the photographs Burton took mid-clearance in the south corner of the Antechamber, where dismantled chariots had been stacked, just-seen number cards single out parts of the chariots and the grid-like structure of a portable canopy frame that might otherwise have been unintelligible (Figure 3.5).

The absence of number cards meanwhile helps indicate the objects that are not objects, namely, the two wooden batons used to prop up a chariot frame to the viewer’s left, after the objects on which it once rested had been removed. Yet the cards were recognized as intrusive as well, too visible to allow the impression that viewers were seeing with the eyes of the last ancient witnesses. Thus, Burton sometimes took one set of exposures with the number cards in place and one without.

The objects in situ were the only ‘before’ shots taken of objects before the cataloguing process. With the exception of a handful of photographs taken in advance of restoration, mainly of jewellery, all other photography was reserved until after objects had been recorded, cleaned and repaired in the laboratory tomb.48 These are what Carter and Mace meant by ‘scale photographs’ – though only a few include a scale in the form of a foot-long ruler, a folding yard- or metre-stick, or an unreeled tape measure. Scale would have been adduced for some objects according to a ratio between their actual size and their size on the glass plate. Otherwise, it seems that the number cards may have offered a rough visual guide to size, even though Burton regularly cropped them out when making prints for album mounting. On the whole, and despite the nomenclature of ‘scale photographs’, object size does not seem to have been a priority in Burton’s object photographs. The photographs were only one part of a whole record system, in which dimensions featured prominently on the main cards for each catalogued object.

Figure 3.5 Dismantled chariots and other objects in the Antechamber, with number cards in place. Photograph by Harry Burton, January 1923; GI neg. P0035.

It is unclear whether the laboratory tomb ever included facilities for developing negatives. If not, the nearest facility was in tomb KV55, situated close by the tomb of Tutankhamun, around the midpoint of the valley (KV15 is at its farthest end). The antiquities service had given KV55 over to Carter’s team, and Burton described in interviews for the London Times and New York Times how they converted the space into an effective, if awkward, darkroom:

It is approached by a flight of twenty-five steps, down a passage 30 feet long, at the end of which four more steps lead down into a chamber 30 feet square. At the foot of the first flight of steps we hung a heavy black curtain, with another at the end of the passage, and when these are drawn I have a very efficient dark room.49

When developing plates, Burton explained, he posted ‘one of my camera boys’ outside the first curtain with his (Burton’s) watch, to call out the minutes as the developer was poured over the negative. In this way, Burton could tell by hearing when the time had passed to take the plate out of the developer and place it in the fixing bath. Checking that he had the shot he wanted would have been vital at stages in the clearance work, before anything was moved, hence the advantage of having a darkroom close at hand. It also made the photographic process at the tomb more visible to observers. Carter and Mace commented that the sight of Burton dashing between the tomb of Tutankhamun and KV55 ‘must have been a godsend’ to the gathered tourists and journalists, since there was little else to see some days.50 But apart from visitors who had privileged access, or readers who saw a handful of sanctioned photographs that appeared in the press, activities in the laboratory took place out of sight.

For the purpose of determining whether he had the shot he wanted in the tomb, Burton only needed to develop a negative, not print it; any prints he did make in the dusty environment of the KV55 darkroom would only suffice as test prints, in any case. More likely, he did much of his printing during the first two seasons at Carter’s house, since the developed negatives were presumably transported there for cataloguing and safekeeping. Beginning with Season 3, the catch-up season after work resumed in 1925, Carter gave Burton permission to take the negatives to Metropolitan House, as Burton reported with evident relief to Lythgoe:

He has consented to my bringing the negatives over here to print, which will be much more convenient and will take much less time. We got a little annoyed with one another one day last week, but I think + hope I shall get away without any trouble.51

If there were no developing facilities in the laboratory tomb KV15, then when photographing objects there, Burton must have trusted his own experience in getting the desired image, even where multiple views were needed to show stages of emptying the ancient boxes or opening one of the miniature shrines. At the laboratory, Burton had recourse to several staging methods for photographing different kinds of objects, in different ways, during the first two seasons: a wooden platform from which he could angle his camera directly over long objects on the ground below; the stand that held a camera over a ground-glass shelf; folded cloths that could be fixed, draped, or held behind objects to isolate them; and a portable roll-down backdrop. In later seasons, he refined these staging methods (for instance, having assistants put the backcloth in motion for a blurred effect in the image background) and developed new ones too, as I discuss below and return to, in more detail, in the next chapter.

Although KV15 was meant to function as a scientific laboratory, that function did not extend to scientific experimentation – or at least, experimentation was never mentioned in the public statements Carter, Mace and Burton made. To admit to experimenting in the context would have been admitting uncertainty, and thus undermining their authority as the only experts who could be trusted with the work. Burton’s photography did involve a degree of experimentation, however, primarily directed towards his main work for the Egyptian Expedition. For the Expedition, he had ventured some new methods at Lythgoe’s urging, in particular the use of colour plates (which Burton had tried before the war, unsatisfactorily) and of a moving-picture camera.52 For most of his work, however, Burton relied on panchromatic plates. These yielded adequate tonal balance and differentiation, which were especially important, but difficult to achieve, among the copious gold and gilding of the Tutankhamun objects.53 Encouraged by Lythgoe, Burton had begun to trial Lumière colour plates, known as Autochromes, in 1921.54 Susceptible to heat and dust, and unstable even when developed (they faded in sunlight), Autochromes became a small but consistent portion of his work for the Metropolitan, and Burton kept them on hand throughout the 1920s, for instance ordering six dozen large-format colour plates from Watson’s photographic supplies in London in the summer of 1922.55 He used this stock to take ‘some colour photos’ for Carter at some point in 1923 or 1924, for which Carter later gave Burton a separate payment of £62.56 While the gold, stones, painted objects and different woods in the tomb might have seemed obvious subjects for further colour photography, it appears not to have been a priority; Carter’s neatly annotated sketches served the function of recording colour well enough. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, monochrome photography was standard for documentary purposes, and would remain so for decades. The absence of colour did not make black-and-white photography less real, but more so. As Peter Geimer has recently argued: ‘It is obviously true that colour – at least as humans experienced it in the visible spectrum – was absent in photography for almost one hundred years. But this absence does not necessarily mean that it lacked’.57 Colour became desirable where images needed spectacular visual impact, rather than a scientific record value. The impact of colour appealed for more popular forms of publication, for advertising or for projecting lantern slides, and in these instances, colour effects could more easily be obtained by hand-tinting reproductions, than by using colour photography. This may have been one factor working against more concerted efforts to take colour photographs at the tomb, likewise the expense and difficulty of printing Autochromes to the standard of book, rather than periodical, publication. Such printing, or the printing of photographic plates more generally, might have been one of the costs Carter had in mind when he claimed that a full publication of the tomb was too expensive to pursue – £13,000, he told Burton over dinner at Luxor years later, in 1934.58

There was another experimental aspect to Burton’s work at the tomb, again an extension of what he was already doing for the Metropolitan Museum: moving-camera footage. The movie camera was a gift to the Egyptian Expedition from trustee Edward Harkness, and its use and issues with maintenance dominated Burton’s correspondence with Lythgoe throughout the early 1920s. Lythgoe’s idea was to film not only the work of the Expedition at Luxor, but also scenes that would convey the flavour of life in Egypt to the Museum’s public in New York. The Egyptian life that Lythgoe had in mind was invariably ‘traditional’, not modern: Burton filmed in the old city of Cairo, around the ruined temples of Luxor, and Egyptian women getting water at a well.59 Filming work at the tomb of Tutankhamun seemed only natural, for use in newsreels or even a feature-length film, as Carnarvon had imagined. The first camera Burton used – and which the London Times photographed him using outside the tomb in 1923 – was an American-made Akeley.60 When this jammed that spring, and had to be shipped to New York for repair, it prevented Burton from filming the transport of the crated objects to the river.61 Such was the interest in filming the tomb, however, that Carter helped arrange for a new cine-camera, a model made by James Sinclair, the London photographic supplier and manufacturer.62 The films had to be developed in New York or London, meaning that of the film he took in the first season, Burton only saw the results in August 1923, when he was in England to visit family and attend his father’s funeral. He explained to Lythgoe that seeing the films had helped him understand how the camera needed to be used, since some of them were failures – either out of focus because of the lens setting or because he had panned too quickly:

The views of the tomb can be done again, but not the couches coming out of the tomb. My only regrets are that I didn’t insist on putting the ‘movie’ on to the removal from the beginning.63

Filming inside the tomb was even more of a problem, because the electric light that was adequate for still photography was inadequate for filming. He tried to film inside the Burial Chamber, but when the films were developed in London, Sinclair sent word that they were a ‘complete failure’, as Burton recounted to Lythgoe:

I am terribly mortified at this failure although I am not wholly to blame. I kept telling Carter that unless he concentrated the light it was a waste of good material + time. His only reply was that I must do the best I could. By the end of the season I felt completely done up by constantly trying to make Carter see reason.64

That failure, though, meant that Harkness arranged to send Burton to Hollywood, to see at firsthand how the movie studios achieved their effects. Burton and his wife had an enjoyable trip across the United States, but Hollywood proved disappointing: the studios were reluctant to reveal their trade secrets, and Burton in any case realized that the kinds of generators and electric lights they used would never work in Egypt. The generators were ‘colossal’ (Burton didn’t think they would make it across the Nile), and the quantity of lights and wattage needed far beyond what the tomb could hold or the antiquities service supply.65

Hollywood glamour may seem a strange fit for the discourse of scientific probity in which Carter and the Museum archaeologists engaged. The excitement and attention of the Tutankhamun discovery did not initiate the use of the latest photographic techniques or promotional activities: Burton was already using Autochromes and a movie camera, and the Expedition’s work, with Burton prominently credited, had featured in the Illustrated London News in 1921, using the same wording that would always appear with his Tutankhamun photographs. In a sense, the first two years of the Tutankhamun excavation confirmed the value archaeology had placed on photography, and confirmed the range of modes in which different kinds of photographic techniques could operate. The ‘record’ photograph, and its archival framework, was part of a coordinated array of visual practices through which archaeology saw its subject matter and encouraged others to see itself. What is just as telling is which of those practices the team would keep, and which abandon, over the course of the Tutankhamun project.

In the more restrained mood that prevailed when work on the tomb resumed in 1925, some aspects of Burton’s photography for the tomb became more restrained, too. Carter himself kept no further diaries (or else they do not survive), and his journal entries became more cursory, apart from an extended description, added to daily, of the mummy unwrapping.66 For the period after Carter’s falling-out with the Service, Burton’s correspondence with his Metropolitan Museum colleagues helps fill gaps in knowing what work was happening at the site, and when, as well as giving voice to Burton’s own views and those of his Metropolitan Museum colleagues. The relationship between Burton and Carter (and Winlock and Carter) was not always easy, nor was Burton’s continued involvement in the Tutankhamun work a given. Writing to Lythgoe in August 1924, after he had seen Carter in London, Burton described Carter as being ‘in a peculiar mood’ and ‘cryptic’ about plans to go on working in the tomb. Negotiations on Carter’s behalf were still taking place, but Burton was left with the impression that work would resume in the new year. Although he told Lythgoe he had no idea whether Carter would ‘allow’ him to continue, Burton ordered adequate plates just in case, together with the requirements for his usual work with Winlock.67

The short third season of early 1925 saw Burton photograph the outermost coffin lying in the basin of the stone sarcophagus, surrounded by the draped and dismantled walls of the burial shrines. Carter spent the season working on objects still left in KV15, such as one of the pair of guardian statues, a series of walking sticks, and the objects found inside and in between the burial shrines. One of these, object 210, was an Egyptian alabaster perfume vase found just inside the doors of the first burial shrine in early December 1923, and stored in KV15 during the cessation of work on site. During that winter before the ‘strike’, Burton seems to have taken a photograph of this virtuoso example of carving, using a piece of hanging (or held-up) fabric, the creases of its fold lines visible (Figure 3.6).68

Returning to the laboratory tomb early in 1925 gave him an opportunity to revisit this arrangement, using a new backdrop he had devised: a paper-lined board of some kind, thin enough to curve around one edge of a round table (Figure 3.7). This set-up was fundamental to his object photography in subsequent seasons, featuring in around 650 negatives. As mentioned above, this was also the point at which Burton reported to Lythgoe that Carter had agreed to let him take the Tutankhamun negatives to Metropolitan House to print at his own convenience.69

Preparations for Season 4 focused on opening the king’s coffins in time for the mummy unwrapping to take place in November 1925, and Carter had asked Burton to be ready for work at the tomb by mid-October.70 Burton complained to Lythgoe that Carter had not given the Museum credit for photographs he used in lectures in London that summer, but Lythgoe could respond by assuring Burton that his photographs had plenty of interest in New York, where prints forwarded by Carter were being framed to make a second public display, after the success of a previous exhibition in 1923.71 Still, frustrations were evident: citing the need for secrecy, Carter would not allow Burton to use the movie camera as he’d hoped to do, to film the coffins being removed from the tomb – but Burton did manage at that point to get Carter to agree that the Museum could have the ‘duplicate’ Tutankhamun negatives. ‘We have a claim on them’, Burton wrote.72

Figure 3.6 Perfume vase (object 210). Photograph by Harry Burton, December 1923 or January 1924; MMA neg. TAA 1054.

Figure 3.7 Perfume vase (object 210) photographed again in early 1925, using a new, curved backdrop. Photograph by Harry Burton, February or March 1925; GI neg. P0524.

This season saw the last of the staged ‘work-in-progress’ photographs that Burton had taken during the first and especially the second seasons, with publicity purposes in mind. As Carter finally opened the royal coffins in October 1925, Burton photographed him lifting back the linen shrouds that covered them (see Figure 5.1), brushing away unseen dust, and, with one of the Egyptian foremen, hammering resin off the innermost, solid gold coffin (see Figure 7.1).73 Each shot was studiously lit and posed, with no blurring from human movement. In November, on the day the mummy unwrapping commenced, Burton marked the occasion with the sequence of formal group shots of ‘the Committee’ discussed in Chapter 1 (see Figure 1.6). During the week-long unwrapping, which took place just inside KV15, work could only be done during the hours of around 8 am and 3 pm, so that Burton had adequate light for photography. His ‘camera boys’, he noted, had arrived just in time to help with the work, though it is unclear from where, and Burton was not happy with what light he did have, although he did make sure to take duplicate photographs. In the end, he reported to Lythgoe that not being able to use the movie camera didn’t really matter: the mummy, which was stuck fast with resin in its coffin and wrapped in brittle, carbonized bandages, was a disappointment compared to mummies the Egyptian Expedition had found and Burton photographed.74

For the rest of that autumn and winter, Burton combined his work for Carter with his work for the Egyptian Expedition: from 8 am to 1 pm, he was either at the tomb or in KV15 with Carter, followed by lunch at Carter’s house; Burton returned to the Metropolitan dig house after 2 pm and worked there into the evening. The work for Carter entailed photographing some of the most splendid objects from the tomb, although Burton felt rushed when it came to photographing the mummy mask and especially the innermost, solid gold coffin, both of which had to be sent to Cairo – accompanied by Carter, Lucas and an Egyptian military escort – at the end of December 1925.75 In April of the new year, Burton returned to photograph the jewellery, having been put off by Carter for a month, for no good reason that Burton could discern. It had been ‘a nightmare’ trying to serve ‘two masters’, since the delay competed with work that Winlock needed him to do for the Expedition. However, Burton’s correspondence makes it clear that he felt unable to confront Carter about this directly, presumably because of sensitivities concerning the Museum’s relationship with Carter and what the Museum still hoped to gain in terms of an eventual division. Instead, he asked Lythgoe to intervene by making Carter aware that Burton’s Tutankhamun work must not interfere with his principal duties to the Museum.76

Perhaps this concern was successfully conveyed to Carter, since from the next season, in the winter of 1926–7, Burton seems to have done his work for Carter in shorter, concentrated periods, during which he kept to the pattern of spending mornings with Carter and afternoons with Winlock.77 There was another advantage that season, from Burton’s point of view: eighty of 160 negatives Carter had packed for shipment to New York had broken when a box slipped from the net as it was being loaded onto a ship at Port Said.78 The loss made Carter grateful for the ‘duplicates’ at his Luxor house, and by the time Burton arrived on site in mid-October, Carter readily agreed to let Burton take all photographs in duplicate – that is, exposing two plates under near-identical conditions – from that point on.79 From Burton’s point of view, this was a victory for the Metropolitan, but Carter continued to reject any use of moving-picture cameras on site.80 Carter was, at least, in a good mood and much easier to get along with, compared to previous seasons.81 Burton’s work that season included a set of photographs of the painted chest found in the first season (box 21), which Carter brought back to Luxor from the Cairo Museum for that purpose. He also photographed a series of gilded wooden statuettes from the two-dozen miniature shrines found in the Treasury. It was exciting to open them, he reported to New York, and he was happy with the photographs he achieved, angling the divine figures against the curved backdrop (Figure 3.8).82

For the shrine statuettes and other sculpture in the round, like the four goddess statues that protected the canopic chest, Burton did not take ‘true’ duplicates, but he did take two different views, by adjusting the angle at which each object stood to the camera. Some of these were subsequently divided by Carter between himself and the Museum, rather generously because there were so many of the statuettes to deal with. The Sekhmet statuette (object 300a) in Figure 3.8 is Carter’s negative, now in Oxford, while a negative showing the object angled in the other direction (facing left instead of right) is now in New York, as are negatives showing the statue when it was still wrapped and depicting the smoothed-out, ink-inscribed linen wrapping itself.83

Figure 3.8 Gilded wooden statuette of the goddess Sekhmet (object 300a). Photograph by Harry Burton, March 1927; GI neg. P1040.

By Season 6, over the winter of 1927–8, all that remained to be done in the tomb was removing the last few objects – in particular, the canopic shrine and its inner chest – from the Treasury, and then clearing the Annex, which was done fairly rapidly in the new year. Burton started his work in mid-October again, tackling a backlog of objects awaiting photography. These needed to be finished to make space in KV15, before the canopic chest and a fragile ship model with rigged sails (object 276) could be brought out of the tomb.84 Burton was pleased that Carter never now questioned the need for duplicates. He described to Lythgoe a ‘marvellous’ bow case (object 335) Carter was working on, of which Burton planned to take ten photographs; in the end he took eleven ‘duplicates’, with one failed negative, for a total of twenty-three exposures.85 Burton finished his work for Carter after photographing the Annex in stages, in early January 1928, but he did another ten days’ work on Carter’s behalf in April, printing Tutankhamun negatives.86 Carter was not oblivious to what he owed the Museum: on this occasion, he made a point of asking Burton to send a set of prints to New York, by the more expensive letter post if Burton thought that was the safest route. Perhaps the recent death of Arthur Mace, which Burton mentions in his own letters, had reminded Carter of the extent of his personal and professional relationship with the Museum.87

With the tomb clear as of early 1928, apart from the dismantled shrines, the next phase of Burton’s Tutankhamun work focused on photographing the objects in KV15 as Carter and chemist Alfred Lucas worked through them; Lucas had retired from government service in spring 1923 in order to devote himself to work on archaeological objects, including the Tutankhamun excavation.88 In Season 7, Burton was set to start work with Carter in late October 1928, but shortly after he arrived, Burton collapsed with dengue fever and needed weeks to recover.89 His planned photography was put off until the new year, finishing only in early March 1929 – by which time Carter had gone to Cairo to commence his negotiations with the Egyptian authorities for ‘the spoils’, as Burton put it.90 These negotiations continued for a year, and although Carter had hoped to work on site in the winter of 1929–30 (he asked Winlock well ahead of time whether Burton would be available), he in fact stayed in Cairo.91 The pause, coupled with the outcome of the negotiations, seems to have given the Metropolitan Museum staff a reason to reconsider their position. With neither a share of the antiquities nor cash compensation forthcoming, would Burton continue to contribute? Lythgoe thought he should, for reasons of continuity: it would be a ‘misfortune to the science’ not to see the work through to completion, if Burton could face it.92

Face it he did. When Carter resumed work in late 1930 (Season 9), Burton was on hand to photograph an impressive chair from the Annex (object 351) that had required extensive repairs, as well as the tomb’s last act of opening and unveiling, when four plastered-over niches in the Burial Chamber were opened, revealing the magic bricks and wrapped figures inside them.93 Through that winter and the next, Carter and Lucas focused on cleaning, repairing and stabilizing for transport the four burial shrines, which had been dismantled in the winter of 1923–4 and spent years, in protective wraps, inside the tomb. They were finally sent to Cairo in 1932 and erected that December in new vitrines on the upper floor of the antiquities museum, where Burton was able to photograph the largest shrine while it was still in pieces in the museum galleries, and all four of the shrines before the glass was put in place (see Figure 1.7).94 Burton took the negatives with him to Luxor to print at leisure in the dig house, together with the final negatives he would take of the sarcophagus in the new year. It was amidst this work that Burton turned his attention to the first set of queries Nora Scott had sent, as she attempted to sort out the Tutankhamun prints and negatives in New York.95 By September, she was still straightening out the ‘Tutankhamun negative mess’ and sent another set of questions, via assistant curator Charlotte Clark (who added that they were still awaiting a batch of negatives Carter had promised to send months before).96 Finally, in February 1934, Burton sat down at the dig house typewriter to deal with Scott’s questions and explain the red and the black numbers, and the real and the not-quite duplicates.97 Just over eleven years had passed since Burton had set up his camera in the Antechamber of Tutankhamun’s tomb. His photography was finished, but the archive was not.

Photography may have been the ‘first and most pressing need’ at the tomb of Tutankhamun, but it was necessary for more reasons than those admitted by the discourse of disinterested science. Built into the daily and seasonal working rhythms of archaeology, photography had an impact far beyond the physical space of the field and the intellectual space of the accurate ‘record’. It required coordination and connections between Luxor and Cairo, and London and New York, by way of several other places in between – the docks of Port Said, the railway station at Naples, or Lythgoe’s summer home in Connecticut, to name just three of the places mentioned in Burton’s correspondence. It also offered opportunities to commemorate the archaeologists at what were deemed crucial points in the work, as well as oiling the wheels of a sometimes difficult collaboration between Carter and the Metropolitan Museum.

Most discussions of Burton’s photography for Tutankhamun’s tomb have focused on what he photographed, and sometimes how, but never at the epistemological, practical and archival issues that informed his work and its subsequent trajectories. Such discussions have tended to assume a single aesthetic for Burton’s photographs, without distinguishing between different aims and settings, or for changes in his approach over time. In the absence of any register of negatives that Carter kept, much less any dated log, the quantity of photographs Burton took, and when he took them, has only been established during my own research for this project, and then only with tentative results, due to the later history of the archive and its current ‘state of play’, in particular the online database created by the Griffith Institute from its holdings in the late 1990s. There is an irony in the mismatch between such a famous body of archaeological photographs and the lack of firm technical or chronological information about them. The dogma of the ‘complete’ photographic record, as a hallmark of ‘scientific’ archaeology, produced a tautology whereby any photographic record characterized as ‘scientific’ was presumed to be ‘complete’. Inadequate photography was always some other, less competent, excavator’s problem. As this chapter has demonstrated, the reality was inevitably more complex, and all the more interesting for its gaps, flaws and foiled attempts.