Not a goddess’s arms but Howard Carter’s reach around the second coffin of Tutankhamun to pull away from the gilded face the shattered red shroud that had covered it (Figure 5.1). Carter’s own face is in shadow, his back to the electric lamp out of shot to the viewer’s left, but the royal coffins are illuminated. Like Carter, they stand on wooden planks across the top of the quartzite sarcophagus. We are back in the Burial Chamber of the tomb, but the doors of the shrines can no longer swing shut: they were dismantled almost two years before this photograph was taken, and the shrines here lean in shrouded pieces against the chamber walls. The space is criss-crossed by the wooden beams erected first to help take the shrines apart, and then to raise the coffins and their lids, unboxing them like Russian dolls. Somewhere inside lies Tutankhamun, waiting for his own photographic moment.

Archaeologists like Carter often emphasized the dull, careful nature of their work, in the process validating its scientific character. Yet when it came to having himself photographed at this dull, careful work, Carter made it look rather interesting, even exciting. That was in part due to the moments he chose for photography, perhaps in consultation with Burton or The Times reporter, Arthur Merton – moments such as opening the shrine doors (see Figure 1.1), breaking through into the Burial Chamber, or here, bending over the pharaoh’s emerging form. The interest was also due to Burton’s photographic choices, which staged the work-in-progress scenes as carefully as his object photography. Inside the tomb, electric lamps made for sharp contrasts between light and dark, while his usual 18 × 24 cm negatives maximized detail and required human subjects to hold still on command, since any movement would blur the shot. Where he thought a composition could be improved, Burton took additional exposures, too: the photograph in Figure 5.1 is one of four he made in close succession on 17 October 1925, two with Carter’s back to the camera, as here, and two with him standing on the other side of the coffin, taking a brush to its face as both of them shared the lamp light.1 One of those last shots was deemed the best, and published in the February edition of the Illustrated London News dedicated to the mummy unwrapping. Carter also included it in the second volume of The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, published in 1927.2 Such imagery has arguably influenced how archaeologists – in particular, male Euro-American archaeologists – have been photographed going about work in the field ever since, merging as it does an aesthetic of discovery and the trope of solitary masculine endeavour.

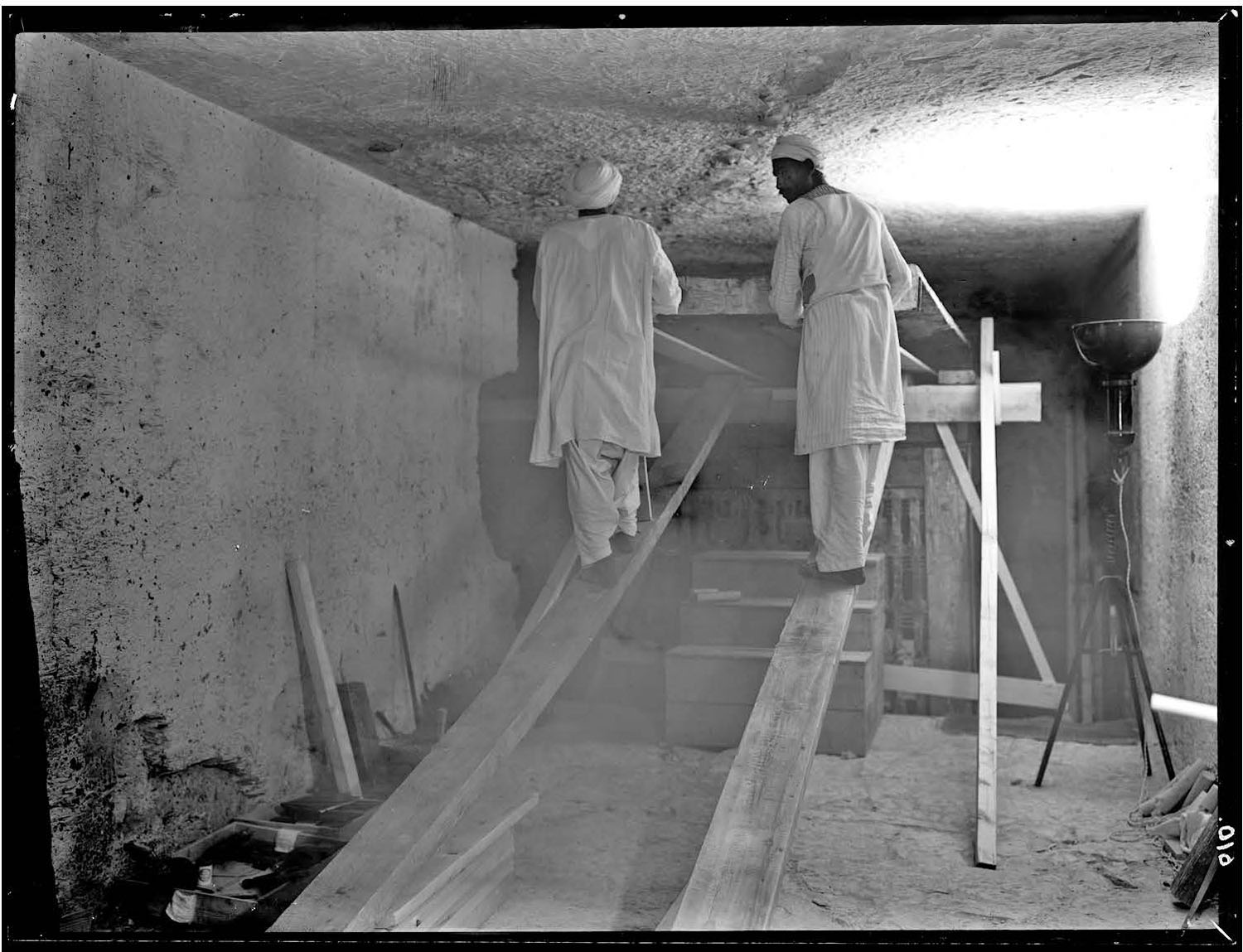

Figure 5.1 Howard Carter rolling the shroud back from the second coffin. Photograph by Harry Burton, 17 October 1925; GI neg. P0720.

This chapter asks why and how the work of archaeology was photographed during the Tutankhamun excavation, and considers how such photographs were incorporated into – or excluded from – the archives formed by Carter and the Metropolitan Museum. The subject matter requires looking beyond the institutional archives of the excavation to a wider archive of press and personal photography, since work outside the tomb, in the open air, was beyond the control of The Times’ monopoly. Some of these press or tourist photographs have subsequently been collected by the Griffith Institute in Oxford, as its archival reach and remit expanded in the late twentieth century. Others can be found in a range of libraries, archives and personal collections, as well as commercial picture libraries and in circulation online. Still others belong to what I have come to think of as a shadow archive: the photographs I have not seen, but which I assume must exist, taken by Egyptian visitors to the site in both personal and official capacities.3 It remains, for now, impossible to say whether photographs taken by Egyptians captured different scenes or different ways of engaging with the Tutankhamun discovery. But of the photographs taken by Burton, by other colleagues, or by Euro-American journalists and members of the public, those that showed both British and Egyptian men engaged in physical labour at the site were defining images of the excavation. Despite or because of this, they have frequently been reproduced without further interrogation, and often without reference to the members of the Egyptian workforce they depict.

The expanded photographic archive considered in this chapter allows us to interrogate the representation of archaeological labour through photography. In particular, I am interested in how photography represented various working processes in archaeology, and how photography itself formed part of the collective effort in the field. Without the evidential value of photographs, much of the labour that went into colonial-era archaeology would remain invisible, even unknown, in particular the roles played by indigenous workmen, as Nick Shepherd has discussed for South African archaeology and Zeynep Çelik for the Ottoman Empire.4 The affective value of photographs, however, is just as significant for the historiography of archaeology, because photographs make visible an embodied experience of labour that sometimes distinguishes foreign archaeologists from indigenous workers, according to who undertakes different kinds of labour – but that also brings them into close proximity due to the various physical demands of fieldwork. As Çelik observes, the relationships engendered by fieldwork were ‘indispensable and intimate’, making their absence from histories of archaeology all the more conspicuous.5 Like Shepherd, Egyptologist Stephen Quirke has noted the invisibility of the indigenous workforce where it is most present, referring to the ‘hidden hands’ that made Flinders Petrie’s long career in Egyptian archaeology possible.6 But it is an absence only in terms of scholars’ persistent failure to see what is in Petrie’s photograph albums (for instance) or give credit to his workers by name, which Quirke was able to do by cross-referencing excavation records, pay lists and Petrie’s diaries.

In the records of the Tutankhamun excavation, no similar evidence survives: only four members of the Egyptian field staff, and one from the photography staff (identified here for the first time) are known by name, and none is ever identified in a photograph. Nor was this convention of anonymity – on both Burton’s and Carter’s parts – exclusive to Egyptians of the labouring class. Where photographs included antiquities or Ministry of Public Works officials, or visiting Egyptian politicians, names were not explicitly recorded in photo registers or albums either, nor have they been of much interest to Egyptologists in the decades since. Yet the existence of such photographs, whether of foremen, porters, camera assistants, or site security guards, argues for a more encompassing idea of who did the work of archaeology – an idea that upends conventional narratives of ‘discovery’ at their source. Moreover, a more encompassing notion of how Egyptians contributed to archaeology in the semi-colonial, interwar era must take into account the staff of the Antiquities Service and Ministry officials who held relevant administrative roles. These men belonged to Egypt’s effendiya class, and many (like Mohamed Shaban, who was near retirement when he attended Tutankhamun’s mummy unwrapping) had been sidelined for decades by the exclusionary tactics of European archaeologists and politicians.7 Correspondence and diaries by men like Burton, Carter and Mace often betray their sense of condescension – or perhaps incomprehension – towards the Egyptian men they worked alongside or, in fact, under, such as the Undersecretary of Public Works whose early departure from the unwrapping Burton took enough issue with to report to Lythgoe. Photographs bring out the texture of these relationships, unwittingly and often in ways that speak to the very fact that they were relationships, not one-directional stereotypes or binary oppositions.

Both archaeology and photography were collective efforts, and as Bruno Latour has cautioned, collectivity is characterized by asymmetry, inequality and anonymity.8 The persuasive discourse of disinterested science seeks to erase considerations of capital or class, but money and the manpower of ‘invisible technicians’ (and overlooked administrators) were what made archaeology possible on many levels.9 This chapter continues as it began, by first analyzing Burton’s valorizing photographs of Carter and other team members – both British and Egyptian – for what they suggest about working relationships at the tomb, including relationships between different workers and Burton’s camera. I then turn to the less formal, journalistic snapshots that documented the more menial work of porterage outside the tomb and between the tomb and the riverbank. Few if any of these were taken by Burton, but their ubiquity in the expanded archive speaks to the significance not only of their subject matter but of the photographic act they represented. Finally, the chapter concludes by considering photography itself as a collective action in which Egyptians participated both before and behind the camera, and from opposite ends of the social ladder. Returning to Burton’s work yields two glimpses of Egyptians in the Tutankhamun archive: one a group photograph of politicians and officials, the other an encounter with one of the ‘camera boys’, a man named only as Hussein. Carter may have believed he was resurrecting a boy-king from centuries of obscurity, but many Egyptians considered it a resurrection of Egypt itself. In the photographic archive, competing visions of what it was to work on and at the tomb of Tutankhamun rupture Egyptian archaeology’s benign self-mythology and reveal the frictions, insecurities and miscommunications that lie beneath.

We now take for granted the immense media interest in the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, an interest which naturalized the act of photographing work on site. Consider, though, that from the early twentieth-century onwards, practical handbooks of how to ‘do’ archaeology offered minute instructions about photographing a site and its objects, recommending tidy trenches, raking light and ground-glass set-ups like the one Burton used.10 None of them mentioned photographing the work as it was being carried out, either by Western or indigenous team members. Their emphasis instead was on how best to light a ruined wall, how to prep a burial for the camera, suggestions for lens types, or the merits of film versus glass negatives. Only George Reisner, in the manuscript of photographic advice he penned in the 1920s, mentioned photographing living human subjects: his expedition at Giza kept a handheld, snap-shot camera to hand ‘exclusively for taking pictures of the men at work, of people and scenes encountered on our travels, and among the local inhabitants where we have worked.’11 Photographing archaeologists at work – whether the foreign expedition leaders or the indigenous labourers – either was not (or not supposed to be) a priority, or was so commonplace and straightforward that it did not require further elaboration or better tools. In the 1970s and 1980s, critiques of colonial photography, often influenced by a Foucauldian interpretation of power relations, saw the objectification of colonial subjects in photographs as inherent to the medium, in part due to the way a photograph gives power to the viewer, whose gaze may travel where it wants.12 However, as Elizabeth Edwards and Deborah Poole, among others, have pointed out, such critiques were overly determined in the way they instrumentalized photography and denied agency to the very people whose subjectivity they sought to restore.13 Instead, taking into account the entire photographic encounter, as well as the resulting image itself, offers a way to consider the multiple human interactions – and perspectives – that photography involved, as well as how the resulting photographs were used and what they show, or purport to show. One of the purposes photography served was the authentication and valorization of archaeologists’ work, but one of the uses to which such photographs can now be put is a reevaluation of how, and by whom, different tasks in archaeology were done.

Archaeologists had been photographing each other for as long as they had been photographing anything, and the archives of many archaeologists contain photos not only of family members and colleagues, but also of indigenous employees, other locals (men and children, more than women), and events such as fantasia performances or – a frequent subject – the workers’ payday. In the 1920s and 1930s, when archaeologists experimented with moving-picture cameras, they tended to film similar themes, suggesting a certain repertoire was thought to be of interest to the audience the films would reach, too.14 Burton’s Tutankhamun films were shown to Metropolitan Museum trustees, along with films of the Egyptian Expedition’s own work, and in 1925, the Museum dig-house staged a show of films for its Egyptian workmen before they broke camp for the summer.15

What most still photographs of work in the field had in common was a certain informality, like the photos that tourists might have taken at the same time. The archaeologists were, after all, tourists of a kind themselves. The photographs’ informality was a function not only of their subject matter, but of how they were taken – with handheld devices like Reisner had recommended, which took roll or sheet film or, at most, small glass plates. There were good technical reasons for this, since film negatives were more portable, and handheld cameras were easier to carry, reposition and operate. But there was also a regime of value at work, just as there was in the way such photographs were included or excluded from excavation archives. It would have been a hassle, not to mention a waste of larger-format glass plates, to dignify archaeological labour with the use of a tripod-mounted view camera.

Yet Burton himself did just that in Seasons 1, 2 and 4 of the Tutankhamun excavation. Using his 18 × 24 cm plate camera required certain physical conditions (adequate light and space) as well as a degree of advance planning. More than anything it required the motivation and will to take photographs that were more formal and staged in their set-up and in their finished look, not to mention more time-consuming to take and develop. In the first season, Burton took just three large-plate photographs showing work in progress – at the ceremonial breaking-through into the Burial Chamber, attended by Lord Carnarvon and his family on 16 February 1923, as well as Pierre Lacau; the undersecretary of the Ministry of Public Works, Abd el-Halim Suleman Pasha; and the Antiquities Service inspectors for Luxor and Upper Egypt. Such was the public interest in this event that all three of these negatives were published in the London Times.16 Each shows Howard Carter with either Carnarvon or, in one shot, Arthur Mace. In two, including the photo with Mace, Burton’s camera faces straight on to the wooden step and ramparts made to protect the guardian statues during the demolition of the wall – and to conceal the access hole at the bottom of it. In these shots, someone off to one side holds something up to shield glare from the electric lamp (Figure 5.2). Burton had little room to manoeuvre, since there were rows of observers behind him in the Antechamber, but for the third shot – in which Carnarvon peers into the Burial Chamber beyond, and Carter looks steadily at the camera – he managed to move the camera to one side. Carter kept all three negatives in his personal collection.

The prompt to photograph this event may have come from The Times itself, or may have been a general and favourable idea among the archaeologists involved. Besides which, The Times contract precluded any other photography. Perhaps encouraged by the success – in publishing terms – of those three photographs, Burton took many more ‘men at work’ photographs in the second season, experimenting with the effects he could obtain. In late November 1923, he photographed Carter and Arthur Callender, with one of the Egyptian foremen, packing the two guardian statues in the Antechamber; this and the statues’ subsequent removal from the tomb was covered by The Times and picked up by other newspapers (see Figures 6.4 and 6.5).17 Around the same time, he also photographed Arthur Mace and Alfred Lucas at work on one of the guardian statues just inside KV15 and in the bay outside the ‘laboratory’, tending to chariot 120 (Figure 5.3).18 Although these photographs were not published at the time, similar photographs, perhaps taken by reporter Arthur Merton, were used instead, creating a picture spread in the Illustrated London News that emphasized the delicate and scientific nature of the work being carried out on the objects – work that only Europeans, not Egyptians, could perform.19

Figure 5.2 Carter and Lord Carnarvon opening the Burial Chamber. Photograph by Harry Burton, 16 February 1923; GI neg. P0291.

Figure 5.3 In the bay outside KV15, Arthur Mace and Alfred Lucas work on a chariot body. Photograph by Harry Burton, November 1923; GI neg. P0517.

The bulk of the ‘working’ photographs that Burton took inside the tomb date from December 1923 and document progress into the Burial Chamber and towards the burial itself: demolishing the rest of the wall between the Antechamber and Burial Chamber, opening and removing the shrine doors (see Figure 1.1), lifting and rolling-up the linen pall that hung on a frame between the first and second shrines, and the arduous dismantling of the shrines – in particular, the first and largest one. In all, Burton devoted around twenty-nine negatives to this process, if one counts those photographs that include human actors or in which the apparatus of the scaffolding, hoist ropes and electric lights dominate. Carter kept all but one of these negatives for himself, passing to the Metropolitan a duplicate negative of the photograph that showed him kneeling before the open shrine doors.20

The choice to photograph these events, and some features of the resulting photographs, suggests a wish to document irreversible actions, in keeping with the archaeological doctrine (however inconsistently applied) of recording something before excavation removed or altered it for good. However, I suggest that the most consistent features in this sequence of photographs are the relationships they reveal between different participants and the camera, as well as a concern with technology and apparatus at this key stage of the work.21 I approach both of these through the concept of photographic affect, and within the context of colonial labour relations.

Elizabeth Edwards has recently argued that the affective qualities of photographs, which have heretofore been configured as a polarity to photography’s evidential, knowledge-producing character, should instead be repositioned in tandem with the evidence base that photographs created and the meanings they accrued.22 ‘Photography has always been a social act,’ she notes, ‘bounded to a greater or lesser extent by power relations’, especially in colonial contexts.23 Taking photographs, being photographed, looking at, sharing, exchanging and copying photographs were such common activities in the field (whether on site, in the dig house or travelling to and from them) that they will have been banal, as were the differences in status – and attributions of agency – both between and among the foreign archaeologists and their indigenous employees. For anthropology, Edwards uses ‘affect’ to encompass the subjective, embodied and emotional experiences of all parties in the fieldwork encounter, to which we can also add subsequent viewers and users of the photographs. For archaeological photography in a colonial or semi-colonial context – and Egypt in the 1920s was arguably somewhere between the two – what photographic images represent is often a form of presence glossed over, forgotten or suppressed in written modes of discourse at the time, and often into the present day.

Photographs also give us glimpses of personal interactions, physical contacts and haptic details that could not or would not be attested in any other medium: the grip of hands on tools or equipment; the texture of clothing, scuffed shoes or (for the Egyptian workers) bare feet; the pressure of bodies pressing against each other; and indeed, the gleam of perspiration on skin or sticking under the arms of a sweat-stained shirt. In the photographs Burton took during Season 2, these affective qualities exist alongside the more hagiographic character inscribed in the composition of the photographs, and in the way some were published. A Burton photograph printed in The Times on 28 December 1923 shows the demolition of the plastered stone wall separating the first chamber of the tomb from the Burial Chamber beyond (Figure 5.4). Wooden planks (courtesy of the site’s carpentry workshop, run by local Copts) protect the burial shrines on the other side. The Times caption – ‘Mr Carter and Mr Callender at work’ – was not unusual in ignoring the presence of the two foremen and a small boy, perched atop the ancient wooden lintel. For all the brute force the demolition required, it also needed care and close collaboration between the British and Egyptian staff. Other photographs in the sequence depict only Carter, at the start of the demolition, or only the Egyptian workers. This photograph is one of two that bring their British and Egyptian subjects together to rather awkward effect, although this did not preclude their publication. In fact, The Times would re-use the other, in which Carter turns to the camera, in 1939 to illustrate Carter’s obituary, cropping it to his upper body and that of the workman or ra’is next to him – Carter, the heroic archaeologist, in action.24

Figure 5.4 Demolishing the wall between the Burial Chamber and Antechamber. Photograph by Harry Burton, 1 or 2 December 1923; GI neg. P0509.

Or was he? In both of the photographs that show him with the Egyptian men and boy, only Carter seems self-consciously aware of the camera’s presence: his pose may look active, but there is no tension in his muscles, unlike the straining forearms of the Egyptian workman balancing on the wooden beam. The second Egyptian man stands in the foreground with his back towards the camera, in a still posture that embodies a sense of expectancy, although it conveys little evident muscular tension. For that, we have to look to the balancing workman and Arthur Callender who waits, back to camera, to receive the chunks of stone the Egyptian man is working free. Despite the valorizing efforts of the tripod-mounted view camera and Carter’s positioning of himself in front of it, these and other photographs taken by Burton to show work inside the tomb are not his most successful in technical terms. Figures – usually the Egyptian workmen – are often out of focus, or where the focus is sharp, it is all too clear which of the subjects, like Carter, is intentionally holding still for the exposure. With difficult work to be done, those being photographed engaged with the photographic process in different ways, or not at all.

For a photograph in which all the actors are in sharp focus, Burton took advantage of a natural pause in the Burial Chamber work, as Carter, Callender and two foremen start to slide the first roof section of the outermost shrine forward from its walls – a tense stage in the task of dismantling these unique objects (Figure 5.5). A New York Times news report about the dismantling of the shrines conveyed the atmosphere and emphasized a silence that was punctuated only by Carter’s occasional commands, although it does not specify in which language they were made. The descriptive account is worth quoting at length:

Three white men, divested of all superfluous clothing, move warily across the eastern end of the mortuary chapel. There is but little air penetrating down in these sepulchral regions, and the strong electric lights provide an unwelcome central heating system. The atmosphere inside the tomb is both tense and oppressive. The faces of the three men at work and those of the native staff standing in solemn silence close by are glisteningly white in the hard glare from these huge globes on either side. Perspiration streams from their faces. One can sense the tense nervous strain.

Suddenly Mr. Carter gives the word. He moves to the corner of the outer shrine and almost fearfully puts his hand on it. The moment has come to continue the task of taking to pieces this great gleaming canopy. […] Mr. Carter stops and surveys his assistants. He gives another word and as gently as a hospital nurse these men exert pressure to bring the woodwork apart. There is no need for Mr. Carter to speak again.25

The account, by an unnamed author, may overplay the silence of the work and underplay the role of the ‘native staff’, but it conveys the tension and the cooperation involved. In the confined space of the Burial Chamber, grappling with fragile and heavy gilded wood, both physical and intellectual coordination were essential. Carter credited Callender, the ex-engineer, with devising the scaffolding, ramps and hoists needed to dismantle the shrines around the royal coffins. But it was the Egyptian carpenters who made these structures, and the Egyptian ru’asa and other workers who undertook the fraught project with Callender and Carter. In the stillness that worked to the camera’s advantage, we glimpse the constant verbal or non-verbal communication such delicate work required, as Carter lays a hand on the arm of the ra’is, perhaps to offer a suggestion as they coordinate their movements. The lamp light Burton has bounced off the ceiling traces the texture of the clothing both men wear and the weight of Carter’s hand resting near his colleague’s shoulder. For all that the gesture may speak of guidance and direction from a superior to his subordinate, it is a physical contact that speaks to close and long acquaintance, too. The London Times published this particular photograph on 18 January 1924, captioned ‘Mr Carter and Mr Callender are seen with native workmen’.

Figure 5.5 Removing the first roof section of the outermost shrine. Photograph by Harry Burton, 16 December 1923; GI neg. P0605.

Carter is, quite literally, the focus of many of Burton’s photographs, whether taking the lead in acts of demolition, gazing into the open shrine doors or captured in lone contemplation, as he was in the 1925 coffin-tending shots (like Figure 5.1) or in photographs that show him seated in the Burial Chamber that winter of 1923–4, taking notes at a point when the shrines had been reduced to their constituent parts.26 The heroic mode of such photographs is indisputable, and even where photographs show him accompanied by Mace and Callender, it is Carter positioned at the front of a group or facing the camera. But the presence of colleagues – British or Egyptian – who ignore the camera, or misjudge its timing, works against the effect Burton may have hoped to achieve at the same time that it betrays the physical intimacy, and at times the tedium, of the work. Notably, Burton also took a few photographs at this stage of Season 2 that show the Egyptian foremen apparently on their own – or that show no one at all, only the carpentry contraption of ramps, steps and scaffold and the ever-present electric lamp, bouncing light off the ceiling. In Figure 5.6, for instance, one of the foremen looks over his shoulder, aware of the presence of Burton (and his own Egyptian assistants), while the other ra’is keeps his back to the camera as if focused on something or someone out of sight at the other side of the Burial Chamber.

Figure 5.6 Two of the Egyptian ru’asa on the ramps, dismantling the shrines. Photograph by Harry Burton, 22 or 23 December 1923; GI neg. P0610.

This particular photograph is at a different angle and has a tighter, closer framing than two or three others taken around the same time, probably on the same day.27 Burton seems to have been seeking the best view, but the best view of what, we could ask? On the Griffith Institute database, the photographs have been associated with the outer shrine itself, as object number 238, yet it is obscured by the men’s bodies and the wooden framework. Considered as a composition, the primary interest of the photograph is the equipment that dominates the picture, placing the simple but effective technology – ramps, levers, the photographer’s lamp, the reflector in the far corner – at its heart.

With no white archaeologist visible in Figure 5.6, the two foremen should be rendered especially present in the photograph, yet there is something in the structure of both the act and the image that keeps the Egyptian men in the background, in every sense. Lacking the strained effect of photographs in which Carter looked directly to the camera, or Mace and Callender tried to hold still, this photograph lacks a clear visual priority. Burton has not encouraged the men to pose for the camera; he has not invited their gaze, nor suggested they turn towards him – or if he did, the invitation was not accepted. It is a curious photograph in some ways, more like a disappointing snapshot than the carefully framed and timed large-format exposure it is. The two Egyptians appear almost incidental to the image, but since they are securely perched on the two ramps, their inclusion must be intentional; other exposures in the sequence always include at least one ra’is.28 Perhaps they are as essential as the apparatus that the rest of the photograph represents – the scaffolding and lighting that were, with manpower and strength, the main tools the archaeologists needed at this stage of the work. From the foremen to the basket boys and girls, Egyptians who worked at the tomb of Tutankhamun were tools of production, contracting their labour to archaeologists who viewed indigenous bodies as capable of performing work that the European body could not.29 Because Burton photographed in the more intimate setting of the tomb, among British and Egyptian men who had long-standing relationships with each other, his more formal images often convey something of that closeness, even when they also gesture to the fundamental inequities of the multivalent relationship between archaeologist and subaltern. It is an uncomfortable paradox of colonial archaeology and similar endeavours: the people with whom archaeologists worked most closely remained most distant, and the people photographed most often have been the most often overlooked.

The most numerous and visible Egyptian participants in the Tutankhamun excavation were the adolescent and adult men who worked as porters or bearers, to use two words associated with them in English sources at the time. In the absence of records like pay books in the excavation archive, it is impossible to identify any of them by name or say exactly where they were from, although most were probably drawn from villages on the west bank of the Nile, the largest of which was Gurna.30 These communities had been supplying and supporting archaeological labour for a century. Most likely, Carter’s head ra’is, Ahmed Gerigar, was responsible for hiring and coordinating labour each season – one of the tasks that made this a powerful role in communities like Gurna.31 Unlike Gerigar and the other three named ru’asa on the site, the porters worked outside the tomb, doing the less specialist, but still delicate, work of carrying objects to KV15. Apart from larger numbers – upwards of fifty men – hired at the end of a season to haul crated antiquities to Luxor, bound for Cairo, no more than half a dozen or so workmen operated on site itself. This was a small and select band.

But who were they? A photograph published in The Sphere – a rival to the Illustrated London News, with which it merged in 1928 – is the only image known to me in which some of the porters and ru’asa are posed for a group portrait, presumably taken by a journalist (Figure 5.7). It is one of five photographs on a single page in the paper’s 3 February 1923 issue, headlined ‘Visitors flock to the Tutankhamen tomb’ with the credit ‘Special Sphere Pictures’.32 Alan Gardiner, in a sun helmet, features in another photograph on the page, while a photograph of the Egyptian soldiers assigned to guard the tomb, lined up at attention with their rifles, describes their attitude as ‘an amusing one’ and characterizes them as ‘bristl[ing] with the lust to kill someone’. The photograph of the Egyptian workmen bears a more respectful, if still anonymous, caption: ‘The men who are assisting Mr Howard Carter’. It specifies that the three men at the back of the photograph are ‘head men’, perhaps meant as an equivalent to foremen or ru’asa. All three can be identified in other press photographs. The two men standing at left and centre are the same men respectively carrying and accompanying the so-called ‘mannequin’ (object 116, Figure 5.8), while the younger man kneeling in the centre appears in several photographs taken for The Times, in which he waits outside KV15 or assists Callender.33

Figure 5.7 Photograph of Egyptian men who worked at the tomb of Tutankhamun, published with the caption ‘The men who are assisting Mr. Howard Carter’ and identifying the three men at the back as ‘head men’. The Sphere, 3 February 1923: 111.

The tall, slim man at the back right of The Sphere photograph may be Gerigar himself, a suggestion I make on the basis that in photographs from several stages of the work, a similar figure appears in postures of authority, instructing fellow Egyptians (see Figure 5.10, far right).34 Gerigar was probably most senior in age as well as rank, which seems to fit the features of the tall man in The Sphere photograph. Moreover, if the men arranged themselves for the photograph, it is possible, if speculative, that this man is intentionally in the most authoritative position, if we read the resulting photograph from right to left, top to bottom, as one reads Arabic script. As Edwards has argued, the space of a photograph is a social one, and social relations may be performed for the camera in ways that defy reductive or polarizing explanations.35 There is an inherent ambiguity here about who was looking at whom, regardless of which faces confront the camera.

Figure 5.8 An Egyptian workman, possibly a ra’is, carrying the ‘mannequin’ (object 116) to the ‘laboratory’ tomb of Seti II (KV15). Press photograph, possibly by Arthur Merton, January 1923.

How little we can say about the Egyptian staff on this most famous of excavations, or even in The Sphere photograph, is in sharp contrast to the coherent and comprehensive narrative that Carter’s journals appear to provide for his part of the work. Photographs offer a corrective, not only on their evidentiary basis – demonstrating the presence, number and at least some of the roles Egyptians performed – but also for what they convey about less formal uses of the camera than the Burton images considered above. The technical differences in the types of handheld, snap-shot cameras used to photograph porterage had a bearing on the kinds of photographs produced, which were not in such sharp focus as Burton’s (especially when enlarged) but could be taken in quicker succession, with shorter exposures and from rapidly changed vantage points. The frequency with which such porterage photographs were taken and reproduced, and the extent to which they still circulate, suggests that there is more at stake in these photographic acts than simply tourist and media interest in the tomb: the Tutankhamun find was exceptional, but it was not an exception in terms of the kinds of activities involved on site. Rather, I argue, these photographs of porterage should be seen as part of an established visual repertoire of empire, in which the representation of non-Europeans as servants and labourers was a commonplace of consumer culture. Advertisements and product packaging in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for example, associated images of indigenous people with products – tea, cocoa, cotton – that originated in corresponding outposts of the British Empire, depicting Africans or Indians as producers or porters of the raw materials. Any Europeans included in such illustrations were in positions of command and supervision, perpetuating the idea of a benign imperialism that had brought its improving and ‘civilizing’ mission to the very people such imagery ‘dehumanized, diminished, and naturalized as servants and inferior beings’, as Anandi Ramamurthy has written.36 The photographic archive is in constant conversation with a wider ‘archive’ of visual tropes and acculturated ways of seeing – perhaps especially when photographs appear at their most diffuse, repetitive, or banal.

Photographing manual labour, like porterage, on archaeological sites meant photographing what were in effect the raw materials of archaeology: the artefacts or structures out of which the archaeologist would manufacture the ancient past. Asymmetries, inequalities and anonymity suffuse photographs of labour at the tomb, not only between foreign and indigenous staff members, but among the British or Egyptian participants themselves; social relations were not binary, but multifaceted. Some of the individuals involved in the Tutankhamun excavation had known each other and worked together for decades, however different their individual experiences were or how difficult the interpersonal relationships enabled (or disabled) by the colonial encounter. Others, like the porters used to transport crates to the river or train station, may have been hired only for specific tasks. Either way, there were a number of social factors in play around, and through, the photographic encounter we see in print.

Photographs of work taking place outside the tomb of Tutankhamun are abundant in two senses, first in terms of the numbers that were taken (and by multiple photographers), and secondly, for the ‘plentifulness, plenitude and potential’ implied in the medium itself.37 Photographs record unexpected details and random information, an ‘excess’ that frustrated earlier photographers but offers a boon to researchers now. The area immediately outside the tomb of Tutankhamun was a photographic free-for-all, however; the cameras of tourists and other news outlets were ever-present, putting many photographs beyond the control of Carter, Carnarvon or The Times during the first two seasons. As an established winter resort, the town of Luxor on the opposite side of the Nile was well-equipped with photographic suppliers, where negatives could be printed on photo paper or postcards. In a February 1923 edition, the Illustrated London News observed that work on site was accompanied by the ‘click of the ubiquitous Kodak’, which the paper juxtaposed with the ‘constant creaking of the crude water-wheels which abound in the locality’, contrasting the modern Western technology of photography with an ageless Oriental primitivism.38 Such photographs were not formally incorporated into the Arabic number sequence Carter assigned to images he associated directly with the tomb, including Burton’s large-format ‘work-in-progress’ photographs. Instead, Carter’s archive in Oxford includes some of these less formal photographs, as both copy and original negatives, in the Roman-numeral sequence he assigned to images he considered more tangential to the tomb, from Burton’s photographs of the Valley of the Kings to his own photographs of work in the Valley pre-dating the 1922 discovery.39 Since the 1970s, the Griffith Institute in Oxford has accepted separate donations of tourist or press images, too, some issued as postcards or at least printed on postcard paper (an inexpensive option at the time), and several that were mounted in a simple, anonymous album.40 In New York, the Egyptian department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art has also over time accrued some postcard-printed shots of work outside the tomb, as well as photographic prints thought to have been donated by Egyptian Expedition member Lindsley Hall, who helped draw the plan of the Antechamber in the first season. Beyond these two institutions, photographs depicting the Egyptian porters at work circulate widely, often in the form of vintage postcards and news agency prints.

The quantity of snap-shot photographs taken, and their frequent reproduction at the time and subsequently, gives the impression that they document the entire excavation. In fact, however, almost all of them date to Season 1, when objects from the Antechamber were transported on stretcher-like wooden trays and could be glimpsed between their steadying or protective bandages. Photographs of the objects being brought out of the tomb focus (or at least purport to) on archaeological objects. But human activity, whether by the Egyptian workers or the ‘team’, was crucial for the visual interest of reportage from the site. The most common photographs show trays of objects being manoeuvred up the tomb steps or carried towards KV15, but The Times also published photographs taken by Carnarvon himself of work areas that were off the tourist track, such as the carpentry workshop.41 Several photographs circulated in The Times and elsewhere of the moment in late January 1923 when the so-called mannequin (object 116) was carried by one of the foremen or site porters, shadowed by his colleague and one of the Egyptian military guards in some views (Figure 5.8), and by Arthur Weigall, Howard Carter or background tourists in others.42 The clear view of the object itself, and the way its head and torso echoed, or in some views almost covered, the body of the man carrying it, provided particular visual interest – helped too by the bright, open-air conditions under which such photographs were taken. Needless to say, the presence of the porters themselves rarely earned even a mention when such photographs were published, nor that of the uniformed military personnel specially detailed to guard the tomb – the ‘amusing’ soldiers deemed by The Sphere’s snide correspondent to be a trigger-happy bunch.43

Given the nature of the portering and transport work, photographs often show the Egyptian and British staff working together to move objects out of the tomb and to KV15. Sometimes, Carter, Callender or Mace adopt a supervisory position, striding along beside a tray carried by Egyptian porters. Other photographs show them pitching in together, however. One of the photographs possibly taken by the Metropolitan Museum’s Lindsley Hall depicts up close the level of coordination and physical contact that the portering work also involved (Figure 5.9). Its intimate vantage point – from near the tomb entrance, rather than the road level above – indicates that it was made by someone on or closely involved with the team, while other photographers snapped away above.44 Divested of his usual waistcoat, Carter and the same Egyptian man seen in many photographs of work inside the tomb struggle together at the top of the stairs with the side of a gilded, hippo-headed wooden couch. The effort of the work is obvious: a ticking-covered pillow cushions the weight of the couch on Carter’s shoulder, and the Egyptian man – one of the foremen, judging by his frequent appearance in these photos – helps lift Carter’s flagging arm. Their intimate contact, hand to arm, knees almost touching, did not preclude publication of this photograph, whose close-up view lent it an immediacy lacking in the photographs taken from ground level. That the Egyptian man adopts, literally, a supporting role to Carter may have matched expectations, and in any case, it is Carter’s face, left hand, and the carved front of the ancient couch that are in sharpest focus. When the weekly Illustrated London News published this photograph in a double-page spread on 17 February 1923, its caption simply identified ‘Mr Carter and an Egyptian’ as the men at work, acknowledging the presence of the second human being while declining to name him. A few months later, Carter and Arthur Mace used the same photograph in their first book about the tomb, this time without either naming the Egyptian man or referring to his presence.45 Both Carter and Mace will have known this man well and worked alongside him on an almost daily basis for months. They certainly knew his name, but they must have assumed either that their readers were disinterested in such a detail, or that it was inappropriate to the task of archaeological record-keeping and publication.

Figure 5.9 Carter and a ra’is struggle with the weight of the hippo couch (object 137). Photographer unknown, January 1923.

Another example of porterage, again probably photographed by someone closely involved, took place in May 1923 when the first load of crated objects was transported by light railway more than five miles to the Nile and loaded on a government barge bound for the museum in Cairo (Figure 5.10). It was a crucial moment: the archaeologists and antiquities officials, including Rex Engelbach, the chief inspector for Upper Egypt, were anxious about the condition and security of the objects along the journey, while the question of whether Cairo would be their permanent home also hung in the background. The London Times – presumably via reporter Arthur Merton – described it as

throughout a fascinating spectacle. The gang which did the manual work consisted of 50 Saidis, or labourers, of Upper Egypt, who are renowned for their industry and endurance. These qualities they fully demonstrated yesterday, and, in addition, most of them displayed marked intelligence in handling and guiding the cars, to each of which three men were attached, the remainder being occupied in raising and relaying the lines.46

Carter and Mace (writing in Carter’s voice) also detailed the transport in their book, but they did not include any of the photographs representing it. As the press report noted, fifty men were involved in the process, which took fifteen hours over two days. They laid and re-laid sections of light railway track as they progressed, an action Carter described as

a fine testimonial to the zeal of our workmen. I may add that the work was carried out under a scorching sun, with a shade temperature of considerably over a hundred [38C], the metal rails under these conditions being almost too hot to touch.47

Figure 5.10 Egyptian porters taking the tomb objects to the Nile at the end of the first season. Photographer unknown, 15 May 1923.

Reading Merton’s and Carter’s words while viewing these images makes both the reading and the viewing more uncomfortable. In Figure 5.10 (negative XV, by his own numbering) a topee-wearing Carter strides towards the front of the train, perhaps to confer with the long-robed figure at the far right of the picture – possibly senior ra’is Ahmed Gerigar, though it is impossible to confirm this. Alongside the crates of royal treasure are the Egyptian labourers carrying the tracks, their short shadows signalling the time of day. In the midday heat, we see where physical collaboration among the collective had its limits, as if only the body of the ‘native’ were impervious to the biology of burns.

At the river, the porters waded into the water to lift the crates onto the boat – and someone was still taking photographs. In one view, two effendiya – perhaps inspectors with the Antiquities Service, like Tewfiq Boulos – adopt the position of command usually reserved for whites in such images: sharp if slightly dusty shoes, crisp suit, tarbush in place, and hands clasped behind back or akimbo at the waist (Figure 5.11). Children watch in the background and donkeys mill about at water’s edge. Egyptians supervising their countrymen welcome the treasures of Tutankhamun to the next stage of their journey, besuited modernity confronting its traditional ‘other’ over the tops of the crates. Wilson Chacko Jacob has argued that effendi masculinity in the interwar era required realigning the self with a new national ideal, in a process that replaced colonial objectification with a new sense of subjectivation, via practices of the self.48 In part, the Egyptian performance of modernity relied on the symbolic value assigned to the fellahin, the peasant farmers coopted in nationalist discourse as Egypt’s indefatigable workforce and essential, pre-modern spirit.49 Whoever took this sequence of barge-loading photographs – The Times reporter Merton, perhaps – may not consciously have had in mind the contrast between effendiya bureaucrats and menial labourers, or between their forms of dress, or yet between the relaxed confidence of the alert inspectors (if that is who they are) and the monotonous strain of the porters’ physical slog. As with Burton’s photographs of the ramps and scaffolding involved in dismantling the shrine, the photographic act here is a function of the noteworthy moment and of the interest arising from the crates and the mode of their conveyance. There is no print or negative of this photograph in the New York and Oxford excavation archives, only in the newspaper archives in which it first circulated, or from which it was recirculated more widely. But read against its archival traces, and in the light of contemporaneous social history, the image speaks to the weight of a past that was carried on the shoulders of many Egyptians – but that was also a platform on which other Egyptians could rise.

Figure 5.11 Two Egyptian officials observe as porters load crates onto the government barge. Press photograph, possibly by Arthur Merton, 16 May 1923.

Absence is in the nature of the archive. Even in what I characterize as the expanded archive of the Tutankhamun excavation, encompassing press and tourist photographs, the most significant absence constitutes the shadow archive of photographs taken by Egyptians, in particular the Egyptian student groups, tourists and officials who came to see the tomb. After 1924, Egyptians working for the Antiquities Service or Ministry of Public Works may have photographed visits made by dignitaries like the Italian prince Umberto of Savoy and his wife, who were shown around Luxor and its west bank by Pierre Lacau.50 However, photographs taken by Egyptians, in any capacity, for private viewing remain outside the institutional archives of archaeology. Indeed, surviving photographs are more likely to be in private hands. Even if some have entered state-owned archives in Egypt, the ‘gatekeeper’ approach and bureaucratic ethos of these institutions today presents certain difficulties of access, for instance determining where a collection of photographs might be, or what photographs a specific archive might contain.51 These are issues that affect research in other decolonizing and postcolonial contexts as well, where archival practices may cut across the expectations of researchers in complex ways.52

The archives of Egyptian archaeology tend to occupy more privileged spaces, whether in metropoles like New York and Oxford for the Tutankhamun photographs or in foreign-owned institutes in Egypt such as the Institut français d’archéologie orientale, which traces its founding to 1880.53 As we have seen throughout this book, photographic material in such archives has been archived and used primarily as a record of antiquities, inscriptions and site features, and after that as a way to illustrate and commemorate white European or American archaeologists – with Harry Burton’s heroic framings of Howard Carter at one extreme, and less formal portraits of individual archaeologists, or camp life, at the other. Among the archive photographs that depict the indigenous Egyptians involved in archaeology, those that show processes of manual labour outnumber themed subjects such as payday or meal breaks (which in any case implicitly refer to manual labour), or portraits like those Flinders Petrie and his colleagues took of Egyptian field and domestic staff.54

But archaeological archives also include photographs that represent middle- or upper-class Egyptian men interacting with Western Egyptologists or paying visits to archaeological sites, for instance in official capacities – especially from the 1920s onwards, in keeping with the changed power relations that Egyptian independence brought with it. An interest in the pharaonic past, and making visits to pharaonic sites, was a hallmark of self-fashioning at the time, central to the cultural and political movement known as Pharaonism and avidly incorporated in new school curricula.55 The Egyptian men who worked for the government, or were attached to visiting delegations in other ways, belonged to the broad social category of the effendiya, which emerged in the nineteenth century as a middle-class, modern elite, distinguished by Western dress and education as well as the forms of cultural expression that its members embraced in literature, the arts and politics, to distinguish themselves both from colonial authorities and from the Egyptian lower classes. It was from the effendiya that the anti-colonial movements leading to Egypt’s independence and early nationhood emerged, although in the interwar period, the title effendi began to lose some of its glamour as other modes of subjectivation supplanted it, broadening the category to include minor bureaucrats and clerks.56 The tarbush and tailored suits were by then ubiquitous for the holders of such posts – including the antiquities inspectors or Ministry employees who appear regularly, but anonymously, in photographs of work associated with Tutankhamun’s tomb, like the two men observing the loading of the crates in Figure 5.11.

In this chapter, we have seen that although the Tutankhamun photographs taken by Burton and others frame the work of archaeology as the preserve of white, male protagonists, it is possible to refigure our approach to these photographs and thus foreground the collective nature of archaeological labour and knowledge production. In this final section, however, I test the possibilities and limitations of this approach by juxtaposing two examples in the Tutankhamun-related archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Both examples help broaden the conceptualization of how many Egyptians, in many different ways, contributed to or identified themselves with the resurrection of Tutankhamun – but both also offer cautions about what the colonial archive allows, or disallows, where Egyptian subjectivity is at stake. Recent years have seen a growing awareness in histories of archaeology and Egyptology that more can and should be done to credit those excluded from the disciplines’ hegemonic narratives, an exclusion taken to comprise Euro-American women on the one hand, and indigenous subalterns on the other.57 In the former case, the danger is that women are simply incorporated into an existing hagiographic paradigm of male scholar-adventurers. In the latter, the difficulty lies in well-meaning scholarship that directs its energy to identifying Egyptians by name where possible, or pointing out their presence in photographs, as if this change in descriptive practice – in essence, a filling in of gaps – were an end in itself, another stage in the purification of Egyptological science.58 Admirable and important as a change in descriptive practice may be, it skims over the depths of the historiographic issues at stake. In her analysis of the social sciences in Egypt during the colonial era, Omnia El Shakry has discussed the challenge of writing a postcolonial history that does more than replicate colonial categories, nationalist narratives, or linear temporalities.59 One of El Shakry’s points is that differing modernities are constitutive and characteristic of modernity. Therefore, it is misguided to assume that gap-filling or ‘recovering’ indigenous subjectivities (I borrow her inverted commas) will magically ameliorate the inequities of past and present.60

Yet archives have an important role to play, and photographs within them can reveal more than they intended, whether read against the grain or read – as my first example shows – at face value. On at least three occasions in the late 1920s, Burton photographed groups of Egyptian officials and politicians visiting the tomb of Tutankhamun and KV15 with Howard Carter. The visits may have happened to fall on days when Burton was working on site, or else he was asked specifically to be there in order to take these group photographs, as he had photographed the gathered archaeologists, doctors and officials ahead of the mummy unwrapping (see Figure 1.6). Whereas Carter numbered photographs of the gathering for the mummy unwrapping in his standard Arabic-numeral sequence, he instead assigned Roman numerals to Burton’s photographs of the Egyptian political visitors, placing these in the more mixed group of images concerned with subjects other than work proper on the tomb.61 In the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Tutankhamun albums, the group photographs of politicians are sequenced towards the beginning of the album set, where they must have been added at a later date. They are mounted alongside other photographs from Carter’s Roman-numeral sequence, as well as prints from Burton negatives that reached the Museum posthumously in 1948 and were numbered by Nora Scott. Many of these album pages have no captions, or else have captions inked directly on the page. But others, including all the Burton group shots, have captions typed on paper and pasted onto the page. It is uncertain exactly when this was done, but since some of the typed captions refer to ‘Griff’ (that is, Griffith Institute) numbers, in all likelihood they date from the early-to-mid 1950s, after Scott and Penelope Fox undertook the collation and print exchange between their respective photograph collections.

Typed labels in the Metropolitan Museum albums identify the November 1925 group photographs from the unwrapping as ‘The Committee’ – a word that does not appear in Carter’s notes or in the second Tut.Ankh.Amen volume, in which he described the unwrapping at length.62 It is a word that suggests scientific or managerial work, so perhaps it was intended as an appropriate and respectful designation of the gathering. Conceivably, it survived in oral recollections of the occasion, only being inscribed in the archive at this later date. However, the typed captions affixed beneath prints of the Egyptian political visits are difficult to characterize as either respectful or serious in their intent: each reads, simply, ‘The Boys’ (Figure 5.12).63

The photograph illustrated here, taken outside KV15, includes members of the Liberal Constitutionalist party, which was elected after Britain forced Sa’ad Zaghloul’s Wafd party from power in 1924. Among the group are no fewer than three past, present and future prime ministers, including Zaghloul’s long-time rival Adli Yakan Pasha, who stands front and centre, facing the camera with his hands resting on his walking stick.64 The second image captioned ‘The Boys’ in the Museum albums was taken on the occasion of one of King Fuad’s visits to the tomb and positions him at the front, with Yakan and Carter next to him at the road above the entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb.65 To date, I have not seen a photograph depicting only white archaeologists captioned in this way, and the captions appear essentially derogatory, specifically with respect to race. In America in the 1950s, ‘boy’ was widely used by whites to address African-Americans, echoing its use in colonial contexts: recall that ‘boys’ was also how Harry Burton referred to the Egyptian youths and men who assisted him with photographic work.66 The album captions may be jocular, certainly – Carter’s presence perhaps lends an element of the tongue-in-cheek here. But jokes are only another way of masking (and revealing) the tensions at play in asymmetrical relationships, as Homi Bhabha and others have argued.67 On the album page, the mimicry of the caption undermines the coevality and equality that the photograph, with its foregrounding of Egyptian masculinity, asserts. Self-assertively modern Egyptian men fill the photographic frame, but the archive denies them any identity other than an insult.

My second example looks to the archive for traces of Egyptian agency behind the camera, where Burton’s ‘boys’ worked. These assistants appear in some of the photographs that show Burton at work in Egypt, doing tasks such as holding a ladder for him, or standing by as he films or photographs (Figure 5.13). In Burton’s own correspondence, he does not refer to any of these men or youths by name, only as a collective, for instance in a letter he wrote to Winlock in 1934:

Figure 5.12 Howard Carter, Adli Yakan and members of the Liberal Constitutionalist party pose outside KV15 – as mounted in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Tutankhamun Albums, page 81. The print corresponds to GI neg. Pkv86 (LXXXVI). Photograph by Harry Burton, date unknown, probably 1926.

Today is the first of the last week of Ramadan. I am always pretty glad when it’s over. My boys are not particularly bright during the Fast + one hasn’t the heart to drive them. I’m also a fellow sufferer as I don’t smoke during Ramadan.68

Burton distances and dismisses the men at the same time as revealing an adjustment he made to his own habits for the Muslim holy month. It is a glimpse of how the relationships that operated in and through colonial archaeology affected the subjective experiences of everyone involved.

Figure 5.13 Harry Burton and his Egyptian assistants, photographing at the tomb of Tutankhamun in the 1920s. MMA neg. MM80950 (film copy negative of a print taken with a hand-held camera).

Like other archaeological tasks, photography was a collaborative endeavour. Burton’s assistants likely had responsibilities that included help with set-up, backdrops and reflectors, but may also have encompassed darkroom tasks, equipment maintenance and supervision of supplies. They are among the unnamed subjects in photographs, and in Burton’s correspondence, but a more personal glimpse of their relationship with Burton emerges in a letter that Burton’s widow Minnie wrote from Cairo to his former employer, Ambrose Lansing, at the Metropolitan Museum, a few months after Burton’s death. It is a revealing letter for what it says about life, and labour, in the contact zone:

The only other person I have heard from of the Luxor staff (except their joint letters of sympathy) was Harry’s Hussein who wrote + asked me to try + help him to find work. But I didn’t know what he was fit for – having, as far as I knew, done nothing but camera work for 20 years or so. He came here to see me the other day + said he was on his way to Suez as he had heard there was work to be found there. Poor fellow – he wept when he spoke of Harry. He told me not to cry. He said “Mr Burton is dead. I too will be dead soon, + so will you + everyone else. Mr Burton was a good man + he is with god, + you will find him there. He knows where you are + what you are doing.” Don’t you think that was extraordinary? It was just about Kurban Bayrami [the Eid el-Adha], so I gave him a pound (Harry always did) + my blessing. He told me the others were all well, except Mr Winlock’s Salama (I don’t remember him) who had died suddenly recently, but I didn’t understand what he died of.69

Like other wives of the Museum’s Egyptian Expedition staff, Minnie Burton had accompanied her husband in Egypt for more than twenty years, living in the dig house and encountering – albeit in more restricted contexts – many of the same Egyptian workmen. A relationship of exchange and responsibility clearly existed between Burton and ‘his’ Hussein, which Minnie as Burton’s widow felt obliged to continue, despite her evident confusion over other Egyptian staff whom Hussein assumes she will remember, and over Hussein’s own fitness for any form of employment other than an archaeological dig. Her letter reports a conversation at the heart of the colonial encounter, where the asymmetries, inequalities and differences inherent to collective effort can be seen behind the camera, as well as in front of it. The click of the Kodak and the shunt of the dark-slide have left us with photographic archives rich with potential to re-enter the contact zone and retrieve something of the embodied and emotional experiences it shaped, in all their confusion, discomfort, or tedious banality. But this is possible only if we look more closely and more critically at our archival sources, which were not designed to enable the resurrection of modern Egypt – only the reinvention of its ancient, idealized past.

Authentication, authority, scientific rigour and security: photographing the work of archaeology enabled archaeology to do many kinds of work, far beyond its purported remit of discovering, recovering and preserving the ancient past. Since the first use of daguerreotypy in Egypt in the 1840s, photographs had documented – and created – a Western presence in exotic lands, a presence concomitant with mastery, control and technical prowess. Even where they show Egyptians and foreigners working closely together, photographs of archaeology thus tap into a seam of enduring visual tropes, which work against reading them as collective effort and instead encourage a reading based solely on inequalities. Those inequalities were real, without a doubt, but so too was a persistent interest in representing archaeology in action. The fame of the Tutankhamun discovery – and, until the 1924 breakdown, the impact of The Times contract – meant that both the British and American team members and the Egyptian workforce were photographed more often, and in a wider array of working contexts, than on most excavations.

What photographs and other archival sources allow us to do is to re-present indigenous participation within the science of archaeology, but also, importantly, to re-examine the discursively produced subjectivity of colonizer and colonized during the early formation of an independent Egyptian state. Histories of archaeology belong to wider histories of labour relations, something Nathan Schlanger has discussed in relation to fieldwork in western Europe.70 In Europe, or Ottoman Turkey, the organization of labour reflected the social stratification that had emerged in industrial societies, anonymizing fieldworkers under collective nouns such as ‘gangs’.71 In colonial contexts like Egypt, where those credited as archaeologists were invariably white men, such stratification was further complicated by race relations and the concessionary privileges that foreign residents of Egypt enjoyed. The participation of Egyptians from a range of social strata has thus been downgraded or ignored, even where they are the sole or primary subjects of photographs taken at the site. Being ‘in the field’ was an embodied reality, not an abstraction. The men – and some boys – who worked at the tomb of Tutankhamun brushed against each other’s clothing and bodies, smelt each other’s sweat, waited, conferred, adjusted, manoeuvred, balanced, day in and day out for months and years. The split seconds caught by a camera may be flattened to shades of grey in the photographic image, but there is a depth and fine-grained texture to the encounters these photographs represent, well beyond the printed surface. The reasons why archaeological labour was photographed are thus inextricable from how it was photographed, as well as how these photographs did, or did not, become incorporated into the excavation archive.

Archaeological archives provide a starting point for interrogating the production of difference and the legacy of colonialism within archaeological labour. Although archives reflect the concerns of the practitioners, almost exclusively Western, who created and shaped them, they nonetheless hold the possibility of historical and disciplinary critique. By studying photographs of work at the tomb, their publication in the press and their various archival trajectories, we can dismantle the narrative of the hero-discoverer and scientific objectivity and try to build in its place a counter-narrative that restores texture, nuance, and complexity to the collective effort of archaeology in Egypt – and that challenges both disciplinary and popular assumptions about Egypt and Egyptology today. Egyptians in their hundreds, and from across the social spectrum, played fundamental roles in the most famous archaeological discovery ever made in their country. They shouldered their past both literally and figuratively, from rough labourers to experienced foremen, and from cooks, cleaners, guards and soldiers to the tarbush-wearing effendiya of the new nation-state’s officialdom, whose Ministry of Public Works oversaw it all. Newspaper and excavation archives show this collective effort quite clearly, for all that it has been underrepresented, if not invisible, in the multitude of books, exhibitions and media Tutankhamun continues to generate. Colonial-era archaeology helped create, reify and reinforce inequalities and injustices that cast long shadows – even if the media-friendly face that Egyptology found in Tutankhamun seemed, and still seems, quite unperturbed.

1 Back to camera: GI negs. P0720, P0721. Facing camera: MMA neg. TAA 371, plus GI neg. P1853 (a film copy negative, c. 1980s, for a print whose original negative is lost).

2 ‘The great golden coffins of Tutankhamen: a triple “nest” of wonderful sculptured effigies’, Illustrated London News, 6 February 1926: 228–9; Carter, The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, vol. II, pl. xxiiia.

3 E.g. Riggs, Tutankhamun: The Original Photographs, 63 (fig. 77), for a Times newspaper photograph in which an effendi pictured in the Valley of the Kings carries a collapsible camera.

4 Çelik, About Antiquities, 135–73; Shepherd, ‘“When the hand that holds the trowel is black”’; Shepherd, Mirror in the Ground.

5 Çelik, About Antiquities, 135.

6 Quirke, Hidden Hands, with discussions of Petrie’s recruitment practices and named workforce at 37–85, 155–270, instances of anonymity at 86–109, and photography at 271–93.

7 Reid, ‘Indigenous archaeology’; Reid, Whose Pharaohs? esp. 172–236; Reid, Contesting Antiquity, 109–33. On the effendiya, in particular its changing composition in the interwar period, see Ryzova, The Age of the Effendiya; Ryzova, ‘Egyptianizing modernity’.

8 Latour, Reassembling the Social, 74–5.

9 Shapin, ‘Invisible technicians’; see also Shapin, Never Pure.

10 For example, Petrie, Methods and Aims and Droop, Archaeological Excavation.

11 Der Manuelian and Reisner, ‘George Andrew Reisner on archaeological photography’, 17.

12 I have in mind here the work of scholars such as Victor Burgin, Allan Sekula (in some respects) and John Tagg.

13 See E. Edwards, ‘Tracing photography’, and relevant discussion in Poole, Vision, Race, and Modernity.

14 For example, Wilfong and Ferrara, Karanis Revealed, 25–34: film taken on this Fayum site in the late 1920s mixed working events (survey, digging, crating up a statue for transport) with scenes of camp life and a wedding procession from the nearby village.

15 For the films being shown to museum trustees: ‘1,036,703 visited museum in year: Increase in attendance attributed to interest in the Tut-ankh-amen discoveries’, New York Times, 22 January 1924: 16; the same article points out that ‘in deference to’ Carter, the Tutankhamun films would not be shown again until his anticipated lecture in New York that spring. Burton reported in a letter to Lythgoe that films including work at Deir el-Bahri and one of Winlock’s mummy unwrappings had been shown to the Expedition’s Egyptian staff: ‘One thing I think I forgot to mention + that was, that we gave the men a cinema show before the camp broke up. We had it on the mandera outside your room + it was a great success + was much appreciated as many of them had never seen a “movie” before’ (letter dated 10 May 1925; MMA/HB: 1924–9).

16 GI negs. P0289, P0290 and P0291.

17 See Riggs, Tutankhamun: The Original Photographs, 13–16. The removal of the statues earned a small front-page notice in the London Daily Express, 30 November 1923, while the Manchester Guardian ran Times-copyright copy the same day (‘Tutankhamen’s statue guardian: delicate removal feat’, p. 9). The relevant Burton photographs are GI negs. P0491, P0492, P0497, P0498, and P0499; MMA neg. TAA 715.

18 Working on chariot: GI neg. P0517, MMA neg. TAA 315. Working on statue 22: GI neg. P0493, plus negs. P0494 and P0495 of the statue on its own.

19 See Riggs, ‘Shouldering the past’. The double-page spread was ‘Preserving and removing: The delicate task of taking Tutankhamen’s furniture from his tomb’, Illustrated London News, 17 February 1923: 238–9.

20 GI negs. P0501–P0510, P0605, P0606, P0608–0610, P0618–P0620, P0626, P0627, P0629, P0630 and P0634–P0637. In addition, Burton took two photographs, with the large-format camera, of Percy and Essie Newberry working on the linen pall on 30 January 1924: GI negs. P0622 and P0623. In the Metropolitan Museum, neg. TAA 678 is a ‘duplicate’ of GI neg. P0626, passed on during Carter’s lifetime; another negative, TAA 1132, is from the group sent to New York from Carter’s Luxor house in 1948.

21 Çelik, About Antiquities, 155–7 also notes the interest in tools and technology that accompanied descriptions and visualizations of archaeological labour, in nineteenth and early twentieth century Ottoman lands.

22 E. Edwards, ‘Anthropology and photography’.

23 Ibid., 240.

24 ‘Obituary: Mr. Howard Carter’, The Times, 3 March 1939: 16.

25 ‘Nerves are taut in pharaoh’s tomb’, New York Times, 9 December 1923: 3.

26 GI negs. P0636 and P0637.

27 The group comprises GI negs. P0608, P0609, P0610 and TAA 1132, most likely taken on 22 or 23 December 1923 judging by Carter’s journal entries on the removal of the shrine roof (see http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/

28 GI negs. P0608–P0610; MMA neg. TAA 1132.

29 On which see Natale, ‘Photography and communication media’.

30 See Van der Spek, The Modern Neighbours of Tutankhamun.

31 For the role of the ra’is, see Doyon, ‘On archaeological labour’.

32 ‘Visitors flock to the Tutankhamen tomb’, The Sphere, 3 February 1923: 111.

33 See Riggs, Tutankhamun: The Original Photographs, 57 (figs. 68, 69, at right), 81 (fig. 107, 2nd right).

34 Ibid., 84 (fig. 112, at right); 86 (fig. 115, seen from back).

35 E. Edwards, ‘Negotiating spaces’.

36 Ramamurthy, Imperial Persuaders, 8. See also Jackson and Tomkins, ‘Ephemera and the British Empire’, 155–64, and McClintock, Imperial Leather for a wider discussion of how race and imperialism were mutually supportive constructs.

37 E. Edwards, ‘Anthropology and photography’, 237.

38 ‘The suggested pharaoh of the Exodus causes an influx into Egypt: Tutankhamen attracts tourists’, Illustrated London News, 10 February 1923: 196–7.

39 Discussed in Riggs, ‘Photography and antiquity in the archive’.

40 Currently catalogued in the Griffith Institute as follows: TAA ii.6.1–20, a small private album of photographs made between 27 December 1922 and 3 February 1923; TAA ii.6.21–4, postcards (or prints on postcard paper) of porterage; TAA ii.6.25–8, four photographs of porterage; TAA ii.6.50, ‘Sport and General press agency copyright’ photograph dated 5 December 1922; TAA ii.6.51–4, four photographs of porterage; TAA ii.6.64, postcard captioned ‘Exploitation of Tout-ankh-amon’s tomb’, apparently from the 1920s.

41 Riggs, Tutankhamun: The Original Photographs, 49 (fig. 57).

42 Ibid., 77 (figs. 97, 98); other examples taken on the same occasion include one of the photographs donated to the Griffith Institute (see http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/

43 ‘Visitors flock to the Tutankhamen tomb’, The Sphere, 3 February 1923: 111. The caption to the photograph of the Egyptian soldiers reads in full: ‘The attitude of these guardians of the tomb is an amusing one. “Never in their lives have they held such positions of rank in the public eye,” declares The Morning Post’s Special Representative. “When Mr Carter emerges to the air or when an object is brought out, the soldiers fairly bristle with the lust to kill someone. Nothing would give the section any pleasure comparable to the unutterable joy of sweeping the front of the tomb with a volley of lead. And if Mr Carter himself interferes …”’. Read against recent Egyptian independence and the 1919 revolution, white fears of indigenous violence clearly run through this alarmist, and alarming, account in a newspaper that circulated widely in the British colonies.

44 An unpublished The Times photograph I have seen online (since taken down) may show Hall or someone else – a slender man in a boater hat – in the act of taking the image. Compare Alamy library image BR6ACR (www.alamy.com), for another vantage point of the hippo couch removal.

45 Carter and Mace, Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, vol. I, pl. xxxii.

46 ‘Treasures of Luxor’, The Times, 16 May 1923: 15+.

47 Carter and Mace, Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, vol. I, 177.

48 Jacob, Working out Egypt, 1–18, 44–64.

49 On the peasant as a representational trope in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Egypt, see Abul-Magd, Imagined Empires, esp. 122–46; Baron, ‘Nationalist iconography’; El Shakry, The Great Social Laboratory, Gasper, The Power of Representation; and Grigsby, ‘Out of the earth’.

50 See Orsenigo, ‘Una guida d’eccezione’, for photographs from Lacau’s personal archive; no photographer is credited, but the prints were made at the studio of Peter Zachary in Cairo. At Luxor, Attiya Gaddis, owner of the Gaddis and Seif studio in the Winter Palace Hotel, photographed important visitors and events, selling his images to the press: see Golia, Photography and Egypt, 57–9. Luxor studios like Gaddis and Seif also did a brisk trade in copies of photographs – for instance, Burton photographs from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

51 As discussed, within a range of related issues, in Ryzova’s insightful essay, ‘Mourning the archive’.

52 Thus Buckley, ‘Objects of love and decay’, who argues that ‘rather than being something aberrant and a stereotypical sign of the neglect and inefficiency of the postcolonial state, decay – as well as the right to allow for decay – is central to the cultural practice of archiving. The desire to preserve the national heritage in these material remains signals the transformation of the former colony into a modern nation and the national attainment of a specific sign of being modern’ (at 250). See also Hayes, Silvester and Hartmann, ‘“Picturing the past” in Namibia’; Hayes, Silvester and Hartmann, ‘Photography, history, and memory’.

53 For the photographic archive of the Institut français, see Driaux and Arnette, Instantanés d’Égypte.

54 See Quirke, Hidden Hands, 271–93.

55 See Colla, Conflicted Antiquities, 121–65.

56 Ryzova, The Age of the Effendiyya; Ryzova, ‘Egyptianizing modernity’.