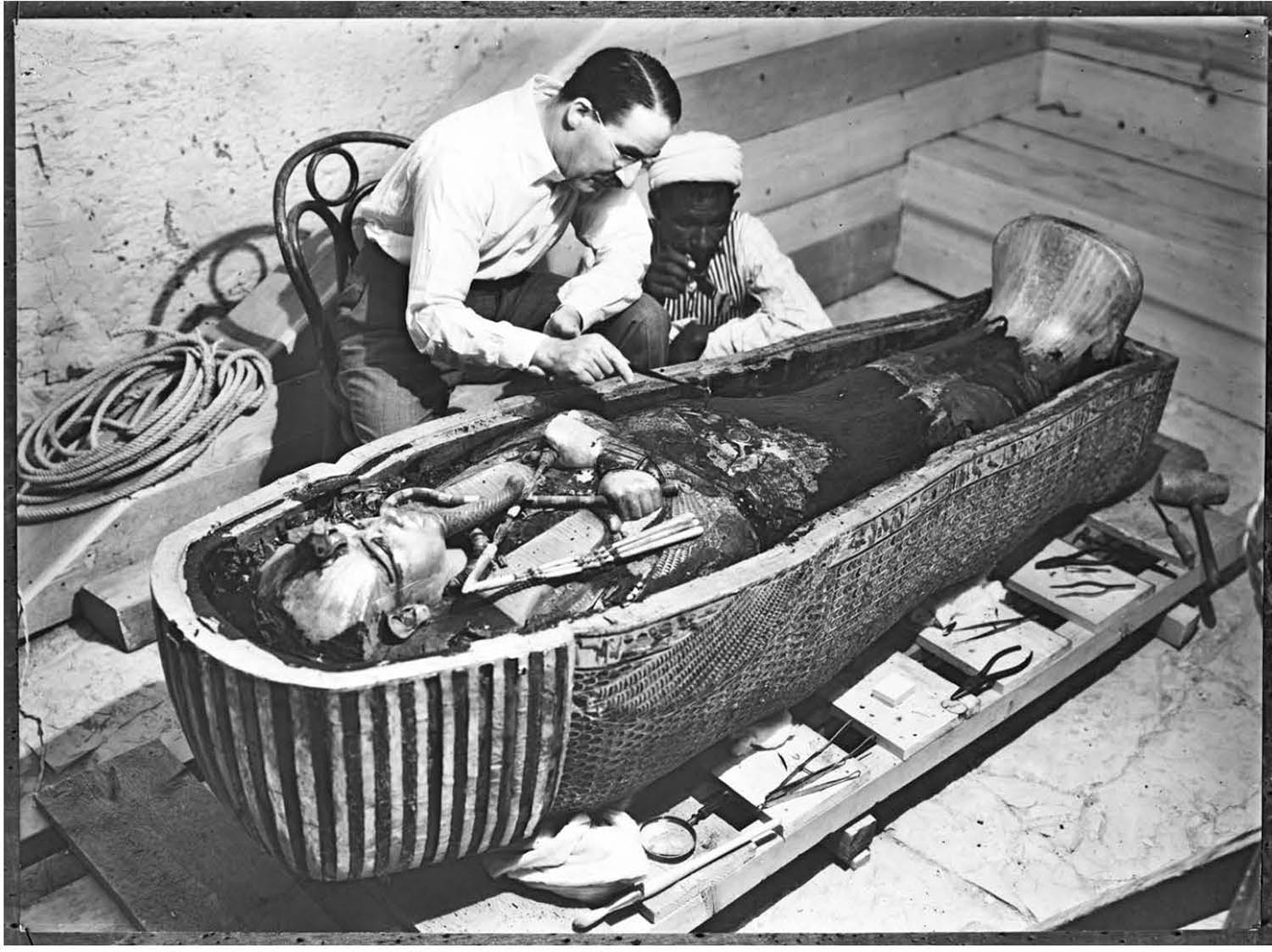

The Churchman’s cigarette card of Howard Carter and a ra’is posed ‘at work’ on Tutankhamun’s coffin turned into bright colour one of the photographs Harry Burton had taken in advance of the mummy unwrapping in 1925 (Figure 7.1).

Published in an issue of the Illustrated London News, with other coverage of the coffins, mask and mummy, there was something about the contrast, clear focus and composition of this image that made it memorable – but only with time, and through modes of circulation other than the various popular or academic books produced about the tomb for most of the twentieth century.1 The photograph was not among those Carter included in his own books in the 1920s and 1930s, although he had kept the large-format negative at his Luxor home, with a copy negative among his London files.2 Nor did Jean Capart or Penelope Fox use it in their books in the 1940s and 1950s, both of which included object photographs rather than ‘working’ shots.3 When French Egyptologist Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt published a best-selling book about Tutankhamun, preparatory to the exhibition Toutankhamon et son temps that she organized in Paris in 1967, she used several Burton photographs as illustrations, as did the popular archaeology writer Leonard Cottrell in his Tutankhamun book, published the same decade – but none of these included the shot of Carter and the ra’is at the coffin.4 The 1972 British Museum exhibition Treasures of Tutankhamun did not include the photograph in its catalogue, written by curator I.E.S. Edwards; neither did contributors to the American version of the catalogue, when the ‘blockbuster’ toured the United States between 1976 and 1979.5

Yet the photograph did find its way into a collective visual memory of the tomb of Tutankhamun – and of the act of archaeological discovery that has been coded so relentlessly and thoroughly as a prerogative of Western masculinity. Other means of circulation, like the cigarette card, may help explain the photograph’s current popularity. Certainly, since the 1990s, it has been included as routine in books, journalism or online features about Carter and Tutankhamun.6 During the writing of this book between 2015 and 2017, it was consistently one of the top two or three returns in Google image searches for ‘Carter Tutankhamun’, and the first in a sub-category of ‘Tomb’ that the search engine automatically generated for that search or for the single search term ‘Tutankhamun’. The neat triangle made by the coffin and the mirrored bodies of the two men may be part of the image’s appeal, but so too are its apparent immediacy and its adaptability: I have spotted at least three mock-ups of the photograph in museum and archive ‘back rooms’, each of which imposed an image of another person’s face (a volunteer or staff member, a visiting media personality) over the face of the Egyptian man. Carter’s own face is never covered. In 2016, the drama serial ‘Tutankhamun’, made for ITV television in the UK, took this trope even further: it eliminated the ra’is altogether from publicity photographs directly inspired by Burton’s 1925 original.7 In these photos, and the corresponding scene in the production, actor Max Irons portrays Howard Carter working in solitude at the coffin, the angle of his body and the frozen action of his hand copied almost exactly from the historic image – apart from the missing Egyptian. The erasure was in keeping with the arc of the drama, which presented Carter as a hot-blooded heterosexual hero, and anyone wearing a tarbush as an enemy of science. Instead of the white-bearded French gentleman that he was, ‘Pierre Lacau’ appeared with dark hair and moustache, his appearance and accented English (he was played by French actor Nicolas Beaucaire) doing little to distinguish him from tarbush-wearing ‘Orientals’ in the background.

Figure 7.1 Carter and an unnamed ra’is posed at work on the innermost coffin. Original photograph by Harry Burton, 25 October 1925; GI neg. P0770, glass 12 × 16 cm copy negative, perhaps dating to the 1920s or 1930s.

This concluding chapter considers the history and legacy of the Tutankhamun photographic archive from the late twentieth century to the present day. Formed under late colonialism in Egypt, the archive and its images had a public face crafted amid the ideals and idylls of imperialism. But even when the photographs slipped from public view and academic interest, the archive itself – and its colonial categorizations of knowledge and values – continued to work within and upon the field of Egyptology. It was tended by the successors of Penelope Fox and Nora Scott, worked on by photography technicians and museum conservators, and preserved as a memory of a ‘golden age’ in Egyptology.8 Any risk of obscurity for Tutankhamun disappeared forever in the 1960s and 1970s, when first Desroches-Noblecourt and then Edwards negotiated at the highest levels of their own and successive Egyptian governments to organize loans of Tutankhamun objects from Cairo to Europe. The boy-king’s second resurrection tellingly coincided with global capitalism’s encroachment on the pan-Arab socialism of Nasser’s Egypt, shortly before and after his death – and meant that Burton’s photographs were resuscitated for new publicity purposes and political ends. How the photographs were used in the Tutankhamun exhibitions is the focus of the first section of this chapter, considering in particular the British and American Treasures of Tutankhamun shows of the 1970s, which saturated public discourse with the gold and glory of Egyptology. The chapter then examines the impact the exhibitions had on the archives themselves, continuing the micro-history of the Griffith Institute archive in order to trace larger trends in academic Egyptology, as it became aware of the public appeal its own past held. Finally, I weigh up some of the multiple versions and alternative archives in which historic photographs of the Tutankhamun excavation now circulate. From digital reconstructions of the tomb, to the Ramesseum rest house on the road to the Valley of the Kings, the photographs offer a looking-glass into which many people peer, as if from habit – but absent a history of the photographs themselves, all these images can reflect are shadows of a colonial past.

An entire book (or more) deserves to be written about the series of loan exhibitions that saw objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun leave Egypt to tour Europe, North America, the Soviet Union and Japan in the 1960s and 1970s. Here, I limit myself primarily to observations about the role that the excavation archives and, in particular, the photographs played in staging these events and repackaging Tutankhamun for late twentieth century consumption. I focus on the 1972 British Museum exhibition and the multi-venue version that toured the United States between 1976 and 1979, since these made use of the respective Oxford and New York archives and in many ways continued the ‘official’ narrative that Howard Carter had presented half a century before. The background to these two related, but distinct, Treasures exhibitions is important to consider as well, in order to understand the political context in which objects from the tomb continued to move – and the ways in which photographs, old and new, accompanied them.

Befitting its dominance in the post-war era, the United States was the first country to which objects from the tomb travelled, as part of an exhibition called Tutankhamun Treasures that premiered at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. in 1961 and criss-crossed the country, visiting regional museums.9 Only a small number of small-scale antiquities were included in the show, which then formed part of the United Arab Republic of Egypt’s pavilion at the World’s Fair in New York in 1964 – a pavilion dominated by news of the Aswan High Dam construction and the UNESCO campaign to relocate the temples of Abu Simbel.10 The tour represented a tentative Egyptian effort to foster ties with the United States, balancing American interests with the Soviet cooperation that President Nasser also pursued. After it left the US, the show stopped at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, while an enlarged version travelled to Japan in 1965–6.

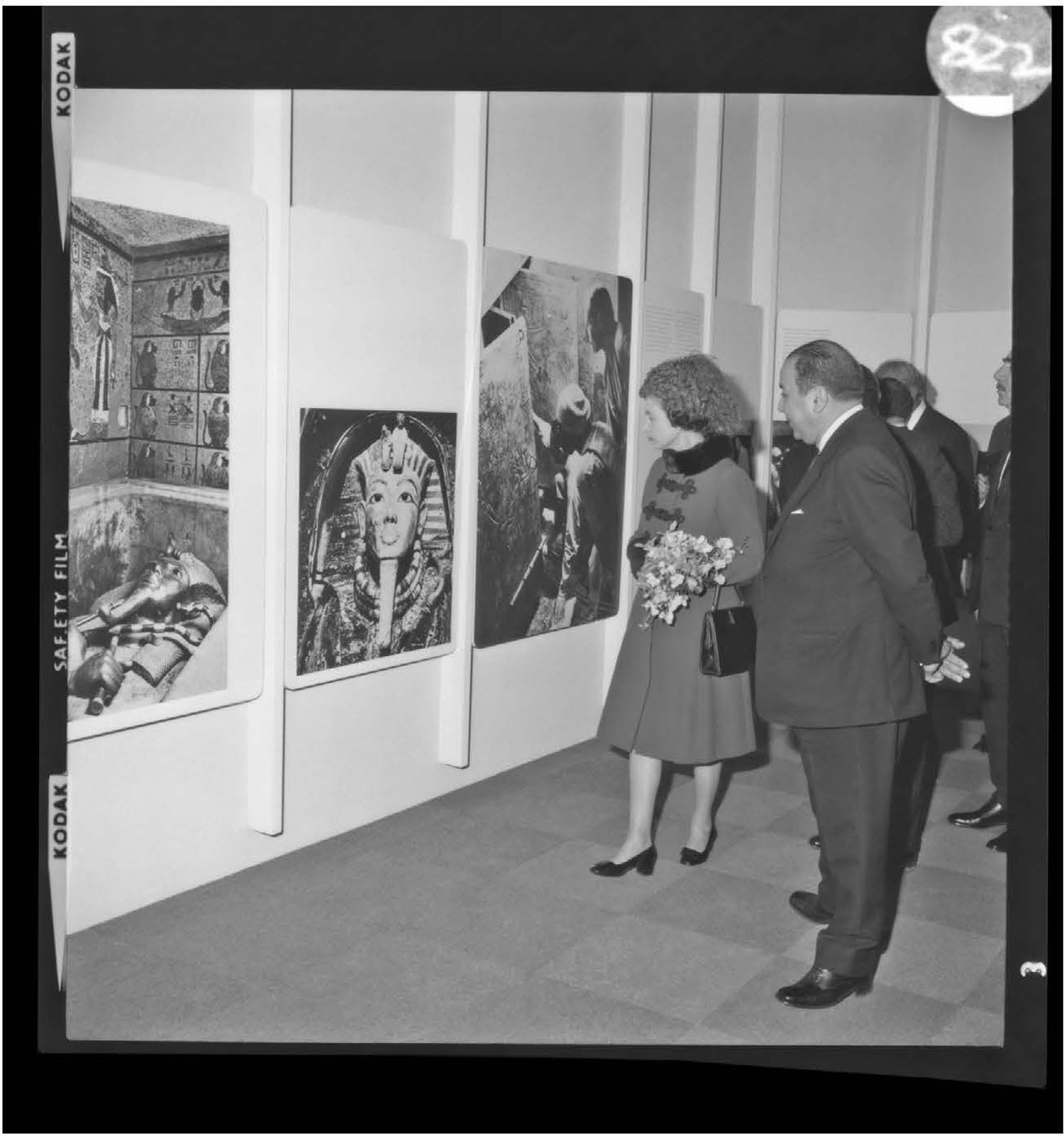

The UNESCO salvage campaign for the Nubian temples, including Abu Simbel, had been spearheaded by the Egyptian Minister of Culture Sarkat Okasha (a close ally of Nasser), with the assistance and advocacy of Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt. A rare, and often sidelined, woman in French Egyptology, Desroches-Noblecourt had been working in Cairo for a project sponsored by France’s foreign ministry – a photographic survey of the temples, carried out under the rubric of an institution called the Centre for Documentation of Scientific Research. She thus enjoyed good relations with the Egyptian authorities as well as an entrée with the French government; UNESCO itself was headquartered in Paris. The reward for France’s efforts on behalf of the UNESCO campaign was a much larger loan of Tutankhamun objects, approved by Okasha and Nasser himself – and including the famed mummy mask, which left Egypt for the first time. It was a prominent part of Desroches-Noblecourt’s exhibition Toutankhamun et son temps, which enjoyed a run of almost seven months at the Petit Palais, from February to September 1967, and attracted more than 1.2 million visitors. The triumphant show was a fitting peak for Desroches-Noblecourt’s long career: she credited the discovery of the tomb in the 1920s – and its coverage in the French press – with sparking her girlhood interest in ancient Egypt.11

In preparing the Paris exhibition, Desroches-Noblecourt made use of the excavation archives in Oxford, where she was also able to consult Alan Gardiner before his death in 1963 – the end of the living memory of the British and American team.12 Her own book on Tutankhamun, translated into English, appeared before the Petit Palais show and was reprinted several times. Apart from one press photograph from The Times, the book drew on the Griffith Institute’s holdings for the rest of its monochrome photographs of the tomb and its objects. These were often edited to help them fit into the book’s small format, both by cropping closely to the image and by erasing the background, so that objects like chest 32 or the folding bed 586 ‘floated’ against the white of the page.13 Close cropping was also used to print one of Burton’s previously unpublished photographs of the mummy’s head, reducing how much of the wooden plinth was in shot – while retouching erased the brush handle propping up the base of the skull (compare Figure 4.14), so that the head also appeared almost to hover in space.14 On the opposite page from this image, Desroches-Noblecourt used another unpublished photograph of the head, at the stage of unwrapping when a double twist of linen still wreathed the forehead and flakes of crumbled textile were strewn on the supporting pillow.15 A caption treated the unmasking and unwrapping of the head as if it were the reverse: ‘The head of the mummy ready for the funerary mask’, read the English caption, encouraging readers to view the photograph through the eyes of ancient embalming priests.16

A highlight of Desroches-Noblecourt’s book was new photography of the Tutankhamun objects taken specifically for the purpose in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo – the first colour photographs made since Burton’s Autochromes more than forty years earlier.17 They were taken by leading art photographer F.L. (Frederick Leslie) Kenett, a refugee from Nazi Germany who settled in Britain and became known for his photography of sculpture in particular. Desroches-Noblecourt’s British publisher, George Rainbird, commissioned Kenett for the task.18 A temporary photographic studio was set up in the museum’s Tutankhamun galleries for the purpose, and thirty-two of Kenett’s new photographs appeared in colour plate sections. The subjects chosen for colour photography, the angle to the camera at which they were photographed, and the level of the camera lens in relation to the object, often create striking echoes of the photographic choices Burton himself had made – no doubt because of certain features of the objects, as they suggested themselves to both Burton and Kennet, but also at least in part because of the influence of the Burton images. Not only had the Burton photographs been published in news media and books, as we have seen, but they had been circulating in the Egyptian tourist industry and the museum itself for decades, as postcards that reproduced monochrome or colour-tinted versions of uncredited Burton prints. Conscious or otherwise, the influence of these earlier photographs on Kenett’s own images seems clear in the colour close-ups of the ‘Asiatic’ figure on a walking stick (object 50uu), the angle and framing of the alabaster perfume container in the form of a boat (object 578) and the isolation of the lion and hippo heads from two of the funerary couches, so memorably captured by Burton in the first season (compare the hippo-head cigarette card, Figure 6.13).19

Burton’s photographs would feature more prominently in Britain’s riposte to the Paris show: the Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition held at the British Museum in 1972, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery of the tomb and signalling the repair of Egyptian and British relations, which had been severely damaged by the 1956 Suez crisis. According to the British Museum curator responsible for Treasures, I.E.S. Edwards, he first made contact with Sarwat Okasha in London in 1966 and tried, but failed, to arrange for the Petit Palais exhibition to travel to England. Another opportunity to bring the Tutankhamun objects to London almost materialized in 1967, through the efforts of The Times editor-in-chief, Denis Hamilton. Hamilton had met Nasser in Egypt during commemorations for the Battle of Alamein. He claimed that although Nasser admitted having rejected Edwards’ initial request, he was willing to reconsider it if The Times sent its best-known photographer, Lord Snowdon (then married to Princess Margaret), to Cairo to take publicity photographs. The Six-Day War of 1967 made this politically unfeasible. Finally, in 1969, Edwards and Okasha met again in London and agreed on the 1972 anniversary as an occasion for a major exhibition. Egypt hoped to receive proceeds from the exhibition to support the UNESCO-backed salvage projects, which may have helped Okasha gain the approval of Gamal ed-Din Mukhtar, the head of the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, and President Nasser. President Anwar Sadat continued this support after Nasser’s death in 1970. On the British side, the Foreign Office lent a hand to the British Museum at every stage, while the office of the Prime Minister was kept informed of developments and progress.20 It helped that the then-chair of the British Museum trustees was Lord Trevelyan, a former British ambassador to Egypt. The Times played its part too, sponsoring the exhibition, providing advertising and lending staff to relevant committees at the British Museum. Denis Hamilton was made a Trustee of the Museum (and later knighted) in recognition of his contribution – an arrangement Edwards found dubious but had to accept.21

The Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition was a diplomatic exercise as much as a public celebration of ancient Egyptian art and British Egyptology. But British Egyptology did figure prominently, and in a flattering light: Edwards retold the tale of the tomb’s discovery and clearance without making any mention of the 1920s political controversy or Carter’s dispute with the Egyptian authorities. This sanitized version may have suited both British and Egyptian sensitivities at the time. Edwards also had to respect the opinions of the Egyptian authorities about which objects could travel, not only for conservation reasons but for concerns about how Egypt – and Nubia – were being represented abroad. A walking stick carved with a bound African prisoner (one of four objects 48a–d) was withdrawn from the loan at Egypt’s request, Edwards wrote, because it ‘offended the susceptibilities of some present-day Egyptians’.22 Those ‘susceptibilities’ may have been about representations of race in general – or representations of Nubia in particular, given the internal discord caused by the forced removal of Nubian populations as a result of the Aswan dam project. Edwards does not mention any other restrictions placed on the loans, apart from concerns about conservation and packing. Fortunately for the British Museum, conservation approval involved another British connection to the 1920s excavation: H.J. Prenderleith, who had briefly advised Carter on material at the tomb, had gone on to head the conservation department at the British Museum, and during the negotiation of the Treasures loan was director of UNESCO’s centre for conservation (ICCROM).23 Unlike the Petit Palais show, which incorporated other objects from Cairo related to Tutankhamun’s reign, the British Museum exhibition featured only objects from the tomb itself. This was an exhibition more strictly focused on the king’s burial goods – and on the British role in finding them.

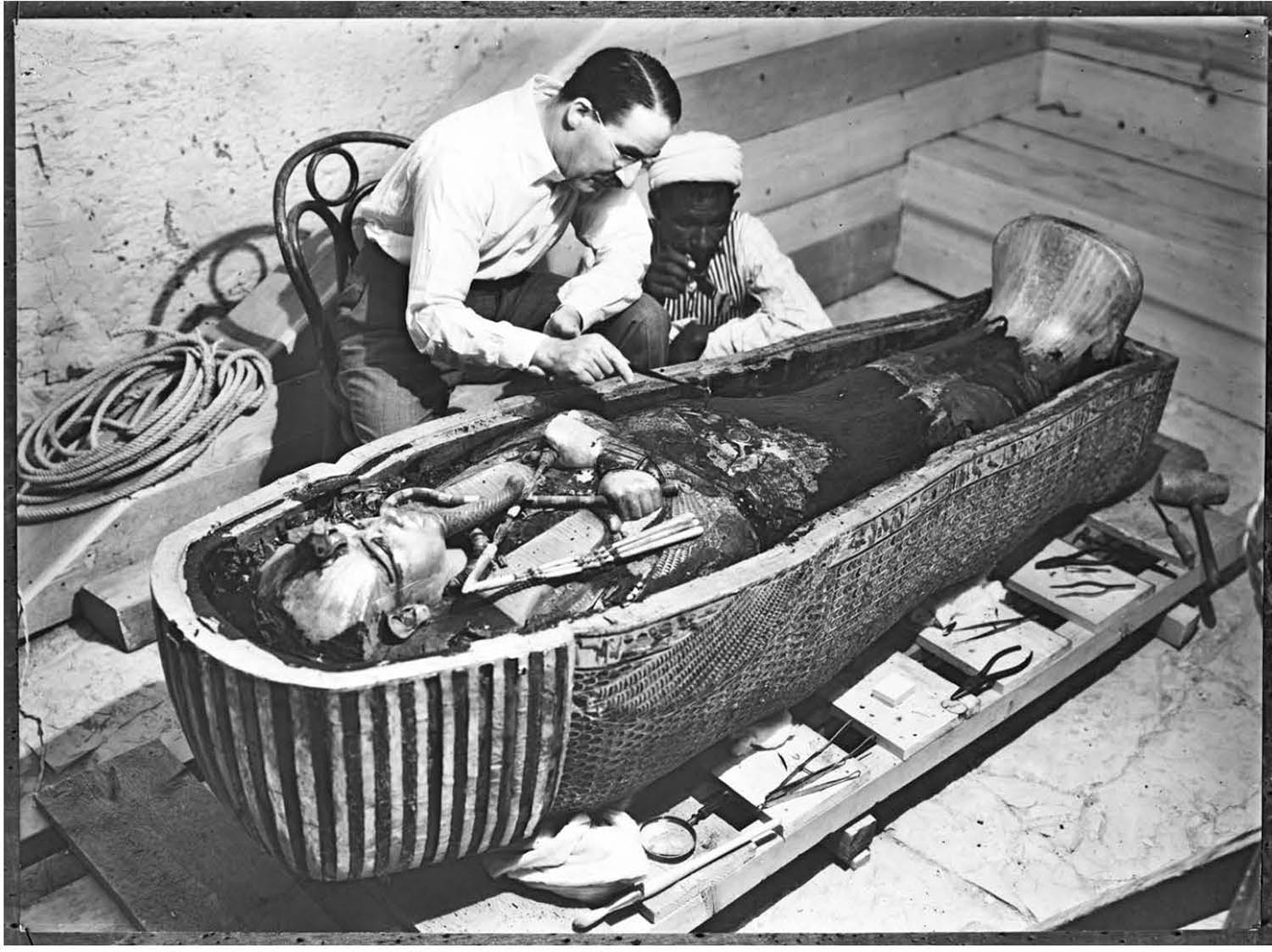

To present the story of the tomb’s discovery, Edwards arranged for the British Museum to borrow documents from the archives of the Griffith Institute and the Metropolitan Museum of Art – and to use 1920s photographs in the catalogue, publicity and exhibition itself. The exhibition team, led by designer Margaret Hall, used sepia-tinted enlargements of Burton photographs in the forecourt of the museum, where the queues of visitors would take in this fabled history before viewing the objects themselves (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Queen Elizabeth II visits the Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition at the British Museum in 1972. The entrance to the exhibition was lined with enlarged prints of Burton photographs.

As The Times’ Norman Hammond described the effect:

One of the most engrossing rooms lacks objects altogether, being hung with enlargements of superb photographs of the excavation in progress and its protagonists, but this prepares the visitor for the glories to come.24

Queue the visitors certainly did: Treasures surpassed all expectations. Its original six-month run, from March to September 1972, was extended until the end of December, with the museum opening seven days a week, including six days of continuous 10 am to 9 pm visiting hours. Visitors queued from early in the morning, with wait times up to eight hours, and the line snaked from the first-floor exhibition galleries (a space freed up by the ethnographic collection’s move to Burlington House), around the forecourt, and onto the surrounding pavements. An estimated 1.65 million visitors saw the show, and it remains the most popular exhibition ever held at the museum.25 One result of its success was a donation of more than £650,000 to UNESCO’s campaign to move the temples of Philae Island, which was to be flooded by the Aswan dam construction. But another was a widespread revival of interest in Tutankhamun, ancient Egypt and Egyptology – a revival whose ramifications continue to be felt today, and a revival that owed much to the purged, heroic narrative of discovery that the show, and its deployment of Burton’s photographs, foregrounded.

The British Museum catalogue made use of Kenett’s colour photographs, several Times photographs from the 1920s, and monochrome photographs of the objects taken by photographers Mohammed Fathy Ibrahim and Sami Mitry in Cairo.26 But just as important were Burton photographs supplied by the Griffith Institute, including images of the ‘untouched’ Antechamber and Treasury, the opening of the shrine doors, and a number of the objects, whether exhibited in the show or used for illustrative purposes in the publication. In the catalogue, these Burton photographs almost always had the background around the object removed so that objects floated on the page, or else the background details were reduced to a solid grey within the rectangular image frame.27 Both treatments helped the older photographs blend in with the new black-and-white photography, even where the resulting grey areas made for awkward blank blocks (around the in situ sarcophagus, for instance).28 The use of Burton’s photographs alongside new ones arguably helped establish the reputation his work had in Egyptology for its sharpness of detail, and confirm the idea that ‘objective’ – and therefore ‘good’ – object photography was timeless. On the one hand, the contemporary look and feel that Burton’s images of the tomb objects had in the 1970s depended on manipulations like those described above, to help them blend in with newer photography. On the other, photographs that were clearly of 1920s date – Carter at work in the tomb, or stages of the mummy unwrapping – benefitted from the rediscovery and re-activation of old photographs taking place in Britain (and elsewhere) at the same time, as local history societies, picture researchers, museums and the media began to turn to overlooked photography collections.29

Besides which, the very existence of the images authenticated Britain’s role in the discovery in the first place – and America’s, which came to the fore when a revised version of Treasures of Tutankhamun toured the United States in the late 1970s. The objects had, in the meantime, visited museums in the Soviet Union, reflecting ongoing diplomatic relations between Egypt and the USSR. In 1974, however, President Nixon visited Egypt to meet with Anwar Sadat, marking a new strategy on both sides in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis and Arab-Israeli war.30 Sadat agreed to lend Tutankhamun objects to the United States – supposedly, at Nixon’s request, ensuring that America had more ‘treasures’ and more venues than the Soviet Union version. The Metropolitan Museum of Art was asked to organize the exhibition, with Henry Kissinger emphasizing to museum director Thomas Hoving that it was ‘a vital part of the Middle East peace process and all future relationships with Egypt’.31 It was also a further stage in the creation of the ‘king Tut’ phenomenon – a phenomenon that, as Melani McAlister has pointed out, did not arise out of the ‘intrinsically fascinating character’ of ancient Egypt, archaeology, or Tutankhamun.32 Rather, it arose through multiple and multi-directional representations of Tutankhamun, which cut across class lines and genres (news media, clothing and trinkets, catalogue sales, Steve Martin’s comedy), and which allowed Americans to reframe a national identity battered by the civil rights movements and anti-war protests of the 1960s. The show opened in Washington, D.C. in 1976, during the bicentennial celebrations for America’s declaration of independence from Britain. It closed three years later in New York, having been seen by 8 million visitors – and having demonstrated that ‘ancient Egypt’ was more American than anyone had realized. In the meantime, Sadat, President Jimmy Carter and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin had signed the Camp David Accords.

For the American tour and the associated catalogue, produced by the Metropolitan Museum, a different approach was taken to photography. Hoving insisted on new colour photography, to take place at the Cairo Museum. His autobiography recounts in picaresque style the alleged lengths he went to in order to secure enough electricity for the photographic equipment, by splicing into the city’s electricity grid.33 Hoving used a photographer who had worked regularly for the Metropolitan Museum, Lee Boltin, assisted by Ken Kay. Boltin and Kay photographed the antiquities against backdrops in jewel-tone colours or jet black, while a sound system played Boltin’s favourite Beethoven, Mozart and Bach. The monochrome images in the catalogue were once again Burton’s. This time, however, they were printed from negatives held at the Metropolitan Museum, supplemented for a few of the catalogue entries by photographs from the Griffith Institute.34 Mimicking the fiftieth-anniversary exhibition at the British Museum in 1972, which displayed fifty objects from the tomb, the American tour was linked to the fifty-fifth anniversary of the discovery (that is, 1977) and displayed fifty-five artefacts. The catalogue Foreword, signed by the directors of all the participating museums in order of hosting, emphasized this difference between the US and British shows – and a difference in the ‘basic theme of their overall presentation’:

Since almost fourteen hundred glass negatives made by the Metropolitan Museum’s photographer Harry Burton throughout the course of the six-year excavation are at the Metropolitan, it was agreed by the participating institutions that these irreplaceable photographs and the actual objects would be brought together into a unique and complementary unity in the exhibition and the accompanying publications.35

American audiences did not need to know Burton’s nationality, or that another archive existed: this was an American tale. New York Times reporter Tom Buckley penned a catalogue essay on the discovery of the tomb, emphasizing the contribution of the Metropolitan Museum’s Egyptian Expedition – and, like I.E.S. Edwards in the London catalogue, avoiding entirely the political fall-out of the find by passing quickly from the first two seasons of work, to a brief mention of the mummy unwrapping, and thence to Carter’s death in 1939.36

Published in a larger format than the British version, the American catalogue of Treasures made more copious use of both colour and monochrome photographs. Notably it reproduced a larger number of Burton’s photographs showing objects in situ or in stages of removal, including the jumble of the Annexe, the clearing of boxes and the raising of the coffins with pulleys and rope. The effect of ‘before’ and ‘after’ photographs can only have contributed to the sense visitors (and readers) had of being part of the excavation: thus one of the king-on-a-leopard statues (object 289b) was illustrated with Burton photographs of it still wrapped in its shrine, and unwrapped in front of Burton’s curved-paper backdrop, while a pen holder and papyrus burnisher (objects 271e, g) appeared both as photographed on Burton’s ground-glass frame and as found inside box 271.37 Colour photographs and close-up views, printed at the front of the catalogue, brought these objects into glittering focus, as visitors would have seen them in the show. But in the course of the exhibition, visitors also followed Carter’s progress through the tomb. The objects were displayed in the order in which they had been found, and enlargements of Burton photographs flanked the cases.38 The museum visitor, or catalogue reader, was encouraged to step into the shoes of the white, male archaeologists and witness the spectacular transformation of jumbled artefacts into works of art.

Despite the slightly altered selection of objects, the changed organization of the exhibition, and the different installation of the Burton photographs (preceding the exhibition proper in London, but an integral part of it in the US), both the British and American versions presented the eponymous ‘treasures’ as works of art, displaying most of them in single, spot-lit cases. This was not an unusual choice in museum exhibition design at the time, but emphasizing their artistic qualities did serve a larger purpose – one that echoes the earlier interpretation of the objects, too. As universal works of art, the artefacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb could be held up as ‘the common heritage of mankind’ – a heritage that was, in Treasures, controlled by the United States and supported by oil giant Exxon.39 Such phrases used a language and an ideology that UNESCO campaigns had begun to articulate increasingly since the 1972 adoption of the Word Heritage Convention, itself inspired by the campaign to ‘save’ the Nubian temples flooded by Egypt’s modernizing dam.40 They were not dissimilar to the claims made decades earlier for the benefits Western science could uniquely, and disinterestedly, offer to the tomb. However much Egypt, like other ‘developing’ nations, used the concept of world heritage to its own ends, the universalizing claims of beauty, discovery and salvage always served Western interests more. Who owned the Tutankhamun objects was a question settled in 1929, when the Egyptian government reimbursed Lady Carnarvon for her family’s excavation costs. Who owned the history and the idea of Tutankhamun was there for anyone to see, from the British Museum’s forecourt to the Seattle Museum of Art. Tutankhamun was also there for anyone to buy: to take Seattle as just one example, visitors exited the exhibition through a museum shop almost as large as the individual galleries, and local businesses offered themed advertising and merchandise. One store promised ‘Egypt: The Ultimate Fantasy’, but a fantasy was what all the products offered, from Boehm porcelain replicas sanctioned by Egypt (retailing at up to $2,700) to an office supply company that offered ‘memories, mementoes, gifts’ (including photo albums) enabling shoppers to ‘enjoy the beauty’ of the Tutankhamun experience for years to come.41 Tutankhamun’s image, and Burton’s photographs, had been commodified already in the 1920s and 1930s, but the scale and saturation of the 1970s manifestation was unprecedented – and its impact on Egyptology as well.

Thanks to the touring exhibitions that proved Tutankhamun’s soft power, the period between the 1960s and the 1980s saw the tomb powerfully imprinted in the public consciousness once again. But the organization of the exhibitions, and the intense publicity they generated, also had an impact on Egyptology itself, especially on the holding institutions in Oxford and New York. At the Griffith Institute, annual reports and correspondence reveal a marked shift from concerns with ‘records’ and academic publication programmes to a self-conscious identity as ‘archives’ that house both the historical identity of Egyptology and the contemporary, globalized appeal of Tutankhamun. The popularization of ancient Egypt that Ambrose Lansing, in New York, had envisioned in the 1940s exploded in the 1970s in ways he could not have foreseen – and saw the Griffith Institute, with its flagship Tutankhamun collection, reconfigured as a specifically archival institution in which photographs and photography played a significant role.

In the wake of Penelope Fox’s work on the Tutankhamun photographs, the Griffith Institute could confidently state in its annual report for 1952, ‘There is now a complete set of all extant negatives of the tomb in both New York and Oxford’.42 In fact, Nora Scott and Fox’s successor as Assistant Secretary, Barbara Sewell, continued to exchange queries about the catalogue of Tutankhamun photographs for years to come. It was Sewell who received Phyllis Walker’s final donation in 1959, comprising the ten Carter photograph albums and an oil portrait of Howard by his brother William, which hangs in the Institute’s archive room today.43 Throughout the 1950s, annual reports document the seemingly endless effort that the Institute’s clerical staff – Sewell in particular – expended on dealing with the ‘records’, as the collections were known. Photographic objects were a substantial part of these records, not only the Tutankhamun material but also photographic collections the Institute had purchased or accepted as gifts and loans since the late 1940s. No wonder the reports for this period regularly comment on the need for more space and improved storage and classification systems in the Institute’s Records Room. By 1957, some of the records were considered ‘in need of a drastic reclassification’, and in the annual reports for that year, the word ‘archive’ makes its first appearance, referring to ‘the Griffith Archive photographs’.44 These would benefit from a card catalogue, the report suggested – and it should be arranged in geographical order, like the Topographical Bibliography, research for which these photographs were meant to support. The group clearly did not include the Tutankhamun photographs, which always retained a distinct identity in the Institute’s operations.

On the assumption that a ‘complete’ photographic record of the tomb of Tutankhamun now existed, the Griffith Institute returned to the question of publishing the Tutankhamun material. As a member of the Management Committee, and the only surviving member of the Tutankhamun team, Alan Gardiner took an active interest in publication plans. He had been calling for some time for a publication that would do justice to the records, estimating that £60,000 would be needed for a ‘scientific’ publication with a description of every object and colour plates.45 It was Gardiner who had secured the contract for Penelope Fox’s 1951 ‘picture-book’ with Oxford University Press, and in conjunction with his eightieth birthday celebrations in 1959, the Institute mooted plans for a ‘serial publication’ of Carter’s notes and drawings, as funds and time permitted. Such a series ‘would be well worth undertaking if it offered the promise of making generally available material now accessible only to those able to visit Oxford, and of permanently recording documents which must inevitably deteriorate with the passage of time’.46 A desire for permanence in the face of decay: if this was a position that sat easily within archaeological thought, it was also a position that reflected the uncertainties of the decolonizing era and the anxieties of the nuclear age.

In 1960, the Griffith Institute announced the creation of a sub-committee to develop the Tutankhamun publication series. A dedicated typist set to work creating a duplicate set of Carter’s handwritten index cards ‘as an insurance against possible deterioration or damage’.47 Work also began on preparing a hand-list of all the objects in the tomb, checked against the Burton prints and negatives in the Griffith Institute. Barbara Sewell began the project, which was continued by the new Assistant Secretary Mary Nuttall after Sewell resigned in 1961 (to become Secretary of the Oriental Institute which had been built next door). Alongside Nuttall, Helen Murray was hired, dividing her time between the Record Room and the Topographical Bibliography. Murray took over the task of typing up the duplicate index cards, while Michael Dudley in the Ashmolean Museum’s photographic service ‘made a complete photographic record of the numerous sketches and drawings appearing on Carter’s cards’.48 Nuttall and Murray’s Handlist to Howard Carter’s Catalogue of Objects in Tutankhamun’s Tomb inaugurated the new Tutankhamun Tomb Series in 1963, shortly before Gardiner died – and just as Desroches-Noblecourt’s book on Tutankhamun was published by George Rainbird.49 Listing each of the objects in Carter’s numerical order, the slim Handlist was ‘received with interest and enthusiasm’ among Egyptologists.50 A Foreword by the Secretary, Near Eastern archaeologist Robert W. Hamilton, blamed history and geography for the long delay:

Up to the present time historical factors have opposed insuperable obstacles to the publication of any comprehensive catalogue of Tutankhamun’s tomb, that almost fabulous treasure being, of course, the property of the Egyptian Republic and preserved in the Egyptian Museum at Cairo.51

The Handlist gave scholars their first indication of exactly how many tomb objects there were, directed them to photographs in the Carter and Mace volumes, and indicated where a drawing existed in the Carter archive; its system of notations also marked all the objects that had not been photographed. Eight further volumes in the new series appeared between 1965 and 1990. Each was illustrated by Burton’s photographs as well as new photography, where possible, and each addressed a class of objects – hieratic inscriptions, chariots, model boats – in keeping with the artefact-focused approach Carter had taken.52

The British Museum Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition in 1972 jolted the Griffith Institute out of these placid academic endeavours – so much so, that it warranted a separate sub-heading in the Institute’s report for the 1971–2 academic year, with a paragraph that merits quoting in full:

Preparations for the British Museum’s exhibition of treasures from Tutankhamun’s tomb, celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of their discovery, the lavish publicity that accompanied them, and the popular excitement generated by the occasion, all kept the administrative side of the Institute and its archive more than usually busy throughout the year. It was common knowledge amongst Egyptologists that the Institute possessed not only Howard Carter’s manuscript records of the tomb but also the set of Burton’s photographic negatives. These contributed in a spectacular and admirable fashion to the exhibition in the British Museum, but could not escape notice also of the press and of innumerable publishers and broadcasting organizations in whom they inspired an insatiable desire for prints and information, stretching the capacity of the staff and photographic studio at times to their limit. To coincide with the opening of the exhibition on 30 March 1972 the Institute itself published the fourth fascicle of its Tutankhamun Tomb Series: F.F. Leek: Human Remains from the Tomb of Tutankhamun.53

The somewhat exasperated tone of the uncredited paragraph highlights several operational assumptions within the organization, as well as the tension its staff perceived between their academic identity as Egyptologists, and the need to engage with the press and other media – ironically, the kind of public profile Lansing had hoped the Tutankhamun photographs might help generate back in 1946. Notably it was the ‘administrative side’ of the Griffith Institute, and the Ashmolean photographic studio, that bore the brunt of this interest, because the interest was so specifically driven by Harry Burton’s photographs, made famous once again.

Whatever ambiguity or annoyance it had felt at the time, in the wake of the 1972 British Museum exhibition and the intense publicity it generated, the Griffith Institute increasingly identified one sphere of its work as archival and itself as an archive. Having first appeared in an annual report in 1957, to refer to other photographic material, the word ‘archive’ occurred only sporadically until the paragraph quoted above.54 Beginning with 1973–4, however, the Institute’s annual report included a sub-head called ‘Archives’, looked after by Assistant Secretary Helen Murray. When Murray retired in 1981, Egyptologist Jaromir Malek, the editor of the Topographical Bibliography, ‘assumed control of the archives’.55 Thus two separate roles held throughout the post-war period by women – editing the Topographical Bibliography (which had been done, without pay, by Rosalind Moss until 1971), and caring for the archives as part of a clerical appointment – merged into a single post held by a man with a doctorate in Egyptology, who was accordingly on a higher, academic-level pay scale. In the 1990s, the creation of an additional job title for Malek – Keeper of the Archives, in line with curatorial titles at the Ashmolean Museum – helped further define the Griffith Institute holdings and lend them institutional prestige.

These shifts in emphasis signal the increasing importance of archive holdings as materials for both research and public-facing activity. The higher profile, and the particular recognition of the Tutankhamun material, led the Griffith Institute to focus more attention on the condition of its photographic objects. In 1980, the Institute commissioned a report from the Ashmolean Museum’s senior conservator, Anna Western, for advice about the care of the Tutankhamun negatives and prints.56 Western recommended that all the negatives should be copied using Kodak SO–015 film, with both the originals and the copies stored in acid-free folders and metal filing cabinets. From the new negatives, a complete set of ‘archive prints’ would be made ‘by archival standard processing’ on non-resin coated paper. These should also be stored in acid-free folders and storage boxes, and never used. As new prints were required, they would be made from the new film negatives ‘so that the original glass negatives are not used again but safely stored in their acid free envelopes in their dark cupboard’. Copies, in other words, would serve the purpose – the image content taking primacy over the photographic objects, including the ‘new’ archive prints. Western also recommended that any Tutankhamun negatives already showing signs of deterioration should be washed to remove silvering deposits and yellow stains; this also appears to have removed some of the masking tape Burton had applied (see Figure 4.7). The Institute acted on Western’s advice immediately: the Ashmolean photographic service took care of washing or re-fixing the glass plates, and Jean Dudley (Michael’s wife) began a two-year long programme of copying the Tutankhamun photographs, completed in November 1983 (Figure 7.3). In that same month, Elizabeth Miles began to work at the Griffith Institute, in a role described as an assistant to Malek.57 Miles searched Carter’s card index of objects from the tomb for any unattested photographs, from which the Ashmolean photographers created further copy negatives – some 300 in total, to which Miles assigned new ‘P’ numbers.58

Technologies of re-photography – which Scott and Fox had deemed too expensive and unsatisfactory to pursue at large scale a generation earlier – now promised an even more ‘complete’ archive of Tutankhamun photographs, this time through the efforts of the Griffith Institute working on its own, with little input from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As early as 1988, Malek and the Institute staff also explored the technological advantage that a computer database might offer. Guided by the Ashmolean Museum’s computer officer, the Institute planned two separate databases: one would replace the Institute’s overall card index of its archival holdings, while the other would be specific to the Tutankhamun photographs.59 In 1995, the Institute secured its own computer network and website, setting the stage for digitally scanning modern prints of all its Tutankhamun negatives – originals and copies alike, with no distinction made between them.

Figure 7.3 A print of box 270b from the tomb (showing it before repair, photograph perhaps by Burton), here re-photographed in the 1980s in the Ashmolean Museum photographic studio, with a 10 cm scale. GI neg. P1825, 12 × 16 cm film copy negative.

This was the beginning of a website called ‘Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation’, which today describes itself as the ‘definitive’ record of the Tutankhamun archive.60 The site includes a database of ‘Burton photographs’, comprising low-resolution files scanned from modern prints of uneven quality, and including photographs taken by Carter and other photographers, such as films and old glass copy negatives of the May 1923 porterage of crated objects by light rail. The quality of the scans is also often poor or indifferent (with uncalled-for cropping, for instance), but at an early stage of the internet, limited web storage capacity and transmission speeds could not accommodate higher-resolution files anyway. Apart from cosmetic changes to the website landing page, the underlying database of the photographs is unchanged at this writing. As with the image quality, data fields and search facilities remain limited by the confines of the early internet age. The platform permits searches by negative or object number, or by the object names used in Nuttall and Murray’s 1963 Handlist. It gives no information about the different formats of negatives or positives held in the Institute archives, the source of the scanned image, or any correlation to the photographic holdings of the Metropolitan Museum, which are not mentioned on the site – presumably based on the persistent assumption that the two collections were identical, and that no more than the 2,000-odd photographs listed in the database exist. For the research and publicity purposes of Egyptology at the turn of the millennium, such details did not matter. The image was the thing, and a complete and total archive of the tomb – not the photographic objects – was the goal.

In New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art did not pursue any specific web-based projects relating to its Tutankhamun photographs or other Burton material, but it did organize two exhibitions around his work. The first, held at the Oriental Institute Museum in Chicago in 2006, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2006–7, focused on Burton’s photographs as a way to narrate the 1920s discovery and excavation. It displayed digital images based on prints known or assumed to have been made by Burton in the Metropolitan Museum’s archive, supplemented by photographs from the Griffith Institute. The published catalogue singled out the ‘Anatomy of an Excavation’ website for praise.61 Five years earlier, another Metropolitan Museum exhibition, ‘The Pharaoh’s Photographer’, had looked at the full spectrum of Burton’s work in Egypt.62 No accompanying catalogue was published, and the show was overshadowed by the destruction of the World Trade Center on its opening day, 11 September 2001. It was co-curated by Egyptologist Catharine H. Roehrig of the Department of Egyptian Art and nineteenth-century photography specialist Malcolm Daniel from the Department of Photographs, each of whom composed a label for the sixty original prints on display. The aim, according to the press release, was to show Burton’s photographs ‘in a dual role – as important historical documents and as works of art in their own right’.63

As we saw earlier in this book, the Museum had displayed Burton’s prints in the 1920s as well, helping to generate, and satisfy, public interest in the tomb of Tutankhamun. But they were not created as works of art. Neither Burton nor his colleagues ever spoke of his photography in such terms, even when the display of his photographs was mentioned in correspondence or the press. ‘Art’ they had become, however, just like the artefacts. ‘Purchase art prints’ is now an option on the homepage of the Griffith Institute, which leads to a sister site where selected Burton photographs, Carter drawings and other material from the archives are available to order as prints or canvases – with the Tutankhamun excavation records in pride of place.64 These are the financial challenges facing academic and cultural institutions in the early twenty-first century, as they balance the responsibility of caring for their archives with pressure to generate income. The 1970s blockbusters cemented the commodification of Tutankhamun, the tomb and the images, as have the various Tutankhamun-themed exhibitions held regularly since, whether involving artefacts on loan from Cairo or reproductions based in part on photographic research. The respected Factum Arte team of ‘digital mediators’ consulted photographs in the Griffith Institute to help create a facsimile of the tomb structure at Luxor, including images of a wall that Carter and his colleagues destroyed in order to extricate the shrines.65 Photographs, and the ‘Anatomy of an Excavation’ website itself, have also played a part in more populist exhibitions based on replicas of the tomb and its objects, several of which have toured Europe and North America in recent years. These generate profits not for Egypt (as tours of the antiquities do, and the Factum Arte facsimile) but for the companies behind them, which promise scientific exactitude and hail the tomb’s ‘invaluable legacy’, even if the result is a simulacrum that copies only an imagined or improved-upon reality, as simulacra do.66 Tutankhamun was made for hyperreality.

In 2015, the Griffith Institute collaborated with German-based SC Exhibitions, commercial exhibition organizers who pride themselves on popular appeal: the SC (from parent company Semmel Concerts Entertainment) is said to stand for ‘Showbiz Culture’.67 In addition to touring the most high-profile reconstruction of the tomb and a thousand of its objects, in three ‘units’ that travel simultaneously worldwide, SC Exhibitions has digitally colourized a selection of Tutankhamun photographs from the Griffith Institute collection, which it displays either separately or in conjunction with the reconstruction.68 The North American version of the exhibition is known as The Discovery of King Tut, while it is marketed in the rest of the world as Tutankhamun – His Tomb and His Treasures. Both are similarly spectacular in their presentation of what the tomb ‘looked like’ and how the objects inside it were arranged. For displaying the colourized photographs, SC Exhibitions uses an audio tour and videos that ‘animate’ the images – panning over or zooming into them, popping colour out from the black-and-white, and adding framing devices. The videos can also be viewed separately on YouTube, where a voiceover tells the by-now familiar tale of triumph, centred on Carter’s heroic perseverance and the ‘expert team’ of white men.69 Lingering over a photograph of the ‘mannequin’ porterage (comparable to Figure 5.8), the narrator tells us that the Egyptian military guard was necessary ‘to deter the ubiquitous thieves and tomb-robbers’. Other videos repeatedly use the words ‘laboratory’ for KV15, ‘conservators’ for Mace and Lucas, and ‘explorer’ or ‘explorers’ for Howard Carter and the rest of the ‘team’, all without any historical context for these terms. Throughout the spoken narrative, present slips seamlessly into past: the present tense describes whatever actions the photographs are deemed to show, while the past tense recounts the use of the objects in antiquity, replete with words like ‘art’, ‘elegant’, ‘exquisite’, ‘gold’ and ‘craftsmanship’. Among the photographs chosen for colourization, and described in the present tense, are several of Burton’s posed work-in-progress shots, including the statue wrapping (Figure 6.4) and Carter rolling back a shroud from the coffins (Figure 5.1). These, and other images, are clearly credited to Burton, while Times photos probably taken by Merton are characterized, in contrast, as ‘amateur’. The video that introduces the ‘expert’ team further emphasizes Burton as a specialist: ‘The art photographer was spending time in Egypt to photograph wall paintings – a godsend for the excavation,’ we are told, as if Burton’s presence were divine providence instead of his usual workaday grind.

The criticism that can be levelled at such simulations is not that they are populist and profit-generating in their aims – but that they perpetuate an apolitical, ahistorical version of the excavation, one devoid of the very context such ventures claim to provide. ‘Context’ in this sense is limited to the archaeological, which is presumed to exist through the reconstructed tomb itself. No other context is needed, and the academic expertise that such commercial firms (unlike museums) lack is compensated for by the participation of professional Egyptologists and institutions like the Griffith Institute. While educational or awareness-raising motives can be claimed for such commercial involvements, generating income is a baseline motivation – like the offer of ‘art prints’ for sale via the Oxford website. Demands on many academic or cultural institutions today far exceed the reach of their core funding, and more traditional ways of underwriting the care of the photographs, such as reproduction fees, have been eroding in the digital age. The Metropolitan Museum and the Griffith Institute consider themselves to share copyright in all the Tutankhamun photographs, and in keeping with agreements made decades ago, they have not levied charges for non-commercial use beyond the basic cost of image supply. Commercial image licensing used to provide a steady income stream, but many photographs associated with the excavation have since entered picture libraries such as Alamy, Bridgeman and Getty Images. The Times asserts copyright in its own images, while copyright in the Illustrated London News belongs to the Mary Evans Picture Library, which licenses images for reproduction, for instance in this book. Inevitably, the nature of photographic reproducibility means that Tutankhamun photographs also circulate freely online or can be purchased, and easily scanned, from vintage postcards or news clippings. As Lord Carnarvon learned long ago, photography is difficult to control.

Egyptology is a field of inquiry boosted at least twice in its history by the boy-king, but it has yet to come to terms with some of Tutankhamun’s most enduring legacies – namely the myths of the hero-discoverer, objective data and disinterested science. An exhibition about the Carter archive held at the Ashmolean Museum in 2014, to mark the Griffith Institute’s seventy-fifth anniversary, took a markedly more sober approach, with concerted efforts to place the find in some historical context and evaluate its impact in popular culture.70 However, it stopped short of disrupting the age-old narrative of science, or questioning the record value of photography. Text associated with enlarged photographs that were part of the display often made no reference to Egyptian workers, only the usual ‘team’ members. Where Ambrose Lansing once hoped the popularization of Egyptology would ensure the discipline’s future, it is the popularization of ancient Egypt and ‘king Tut’ that now seems to mire Egyptology in the past – a past of colonial asymmetries and imperial assumptions. The archival turn that Egyptology began to take in the 1970s, in part amidst the organization and promulgation of the Treasures exhibitions, has rarely turned towards historical critique and self-examination – in sharp contrast to the cognate fields of anthropology, art history and several strands of archaeology. Archives and their photographs have variously been overlooked, mined for ‘data’ on sites or artefacts, or used to promote Egyptology in its most conventional articulations, within and without academia. With its habit of looking only at the artefact, or the famous archaeologist, in a photographic image, Egyptology too often treats its archives as mere surfaces – reflecting back the same mystic mauve or golden glow in which Carter once knelt before Tutankhamun’s burial shrines. The field has to date found no need to look closely at itself, when there are such wonderful things to admire instead.

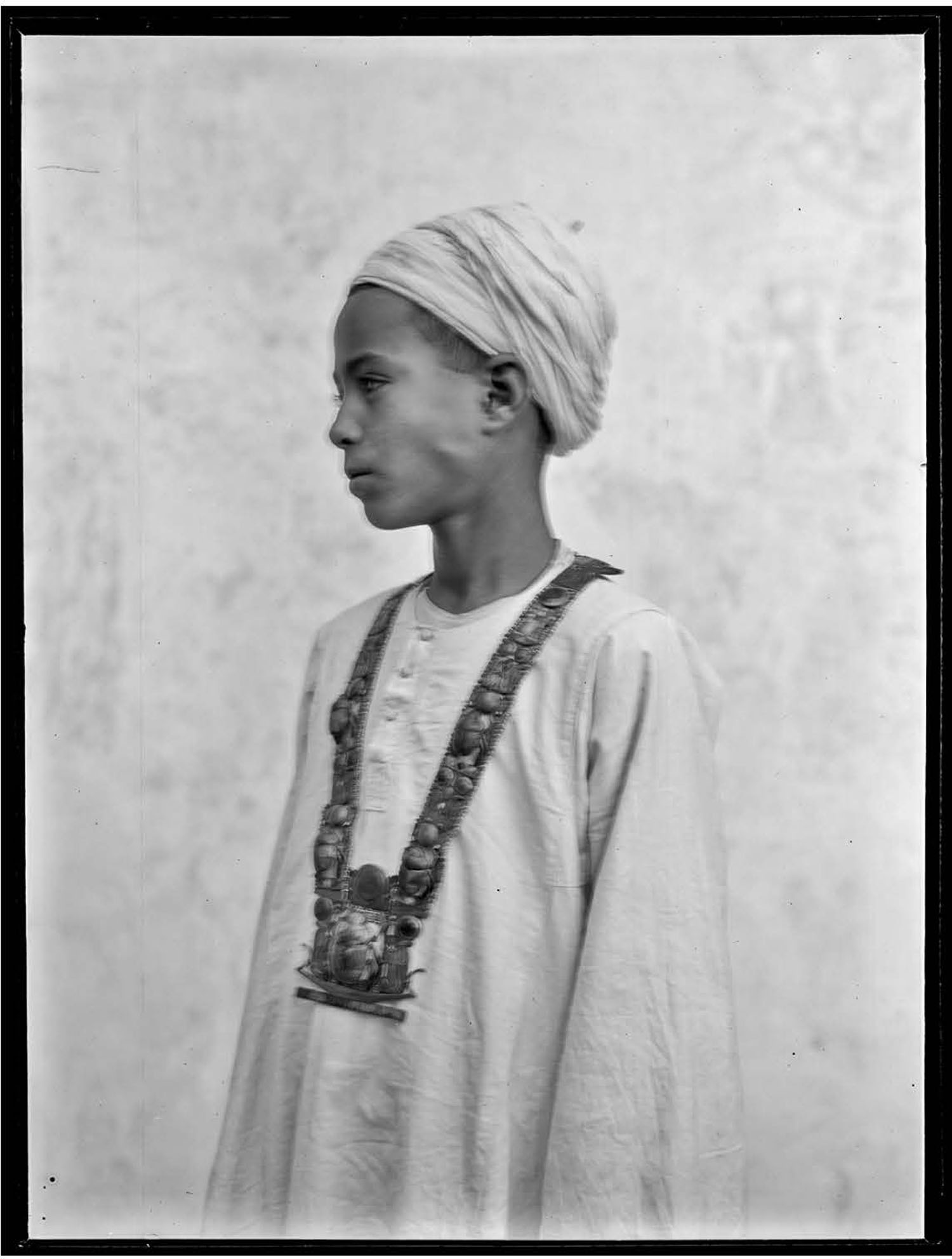

Some time towards the end of 1926, or early in 1927, Harry Burton took four photographs of an Egyptian boy wearing what was his customary long robe and wound turban – but with the unusual addition of a heavy jewelled necklace and pectoral, found in one of the many boxes in the tomb’s Treasury (Figure 7.4).71 ‘Tutankhamun’s honorific orders’, the Illustrated London News called this and other examples of jewellery found in the tomb, aligning them with the British civil and military honours system. Under that heading, the paper published one of the photographs of the boy, captioned, ‘A living Egyptian boy wearing the 3000-year-old order of the birth of the sun: a photograph taken to show the method of suspension over the shoulders’.72

Who this ‘living Egyptian boy’ was, neither Carter nor Burton ever mentioned, nor it seems did Burton print the negative reproduced here as Figure 7.4, where a slight movement has blurred the boy’s features and his jaw is clenched tight as if with nerves, embarrassment, or strain. A later print, with typed ‘Griff[ith]’ caption, is mounted with the others in the Metropolitan Museum albums, in between photographs of the necklace itself laid on ground-glass to isolate it from both the bodies of living boys and the boxed-up grave goods of dead kings. In the Griffith Institute online database, the photographs are tagged by the object numbers of the pectoral and necklace: 267g and 267h. The boy himself might as well not exist.

Figure 7.4 An Egyptian boy wearing a necklace and pectoral from Tutankhamun’s tomb. Photograph by Harry Burton, November or December 1926; GI neg. P1190.

So far, so familiar. Except that the preferred photograph – the version printed in the Illustrated London News – lives another life, in an alternative archive. Hussein Abd el-Rassul, who bore the honorary title sheikh, was a member of the large Abd el-Rassul family on the west bank of Luxor, in and around the village of Gurna. The family gained notoriety in the late nineteenth-century as robbers (never ‘explorers’) of a cache of royal tombs. Like other Gurna families, they had a symbiotic relationship with the twin trades of archaeology and tourism in the area. Hussein was the proprietor of the tourist rest house – a café and shady resting place – that has been running for several decades, near the Ramesseum temple. Inside hang several copies of Burton’s photograph, either on its own or cradled, in a gilded frame, by the elderly Sheikh Hassan to make a photograph-within-a-photograph. Hussein has been described in recollections by many tourists as a basket-boy or water-boy on the Tutankhamun dig.73 A Swiss author who was once married to Hussein’s grandson Taya also identified Hussein as the boy crouching near the ceiling in photographs of Carter ‘demolishing’ the wall to the Burial Chamber (such as Figure 5.4), and named the boy’s father as the like-named Hussein Abd el-Rassul, said to be one of Carter’s foremen.74 Others have disputed Sheikh Hussein’s claims: Carter, who pursued members of the Abd el-Rassul family when he was an antiquities inspector at Luxor, did not name any of them among his four ru’asa, and some residents of Gurna have denied any resemblance between the boy in the photograph and the adult Hussein. The skin colour was wrong, some reasoned – skin colour being a physical trait to which many Egyptians are attuned after centuries of Ottoman and European colonialism.

Whether or not young Hussein Abd el-Rassul was the boy in Burton’s photograph matters much less here than the point that layers of photographs, and memories, hang on the walls of a building that serves as a meeting place for local people as well as tourists and archaeologists. It is a glimpse of the other stories that photographs can tell – and of the alternative archives that exist outside the institutional archives of the Tutankhamun excavation, or the press archives and photo libraries through which the tomb and its treasures have also been refracted. Writing for National Geographic Magazine in 1923, Maynard Owen Williams photographed what he assumed were Egyptian journalists, waiting with their cameras at the tomb. They were, in fact, a group of students from the Giza Polytechnic Institute, whose visit was reported, and photographed, in the Times that February.75 What photographs Egyptian visitors like these took, and what happened to those images over the course of the ensuing century, is what I have characterized as a shadow archive, and trying to locate it has been beyond the scope of my research for this book, likewise any detailed consideration of photographs and other images that circulated in the Arabic-language press. But like the repurposed Burton photograph in the Ramesseum rest house, the students’ expectant cameras point to the absences and exclusions inherent to the ‘official’ photographic archive of the tomb. The photographs that Harry Burton took are not the only photographs of Tutankhamun’s resurrection – only the most widely reproduced. To generations steeped in the lore of Carter’s discovery, they have offered flattering reflections of an ancient Egypt, and an Egyptology, untouched by time and unmoved by history. We see with compromised eyes.

Archaeology needed photography. Not as a record, as archaeologists are still taught to regard the photograph, but as a way of being, doing, and making visible what archaeology was – or what it wanted to be. This book has argued that acts of archaeological discovery hinged on questions of vision and knowing, in which photographic technologies were deeply enmeshed. Camera work was anxious work, as we have seen throughout this book. It required negotiations, supplies, collaborations, and, not infrequently, serendipities, even for images as controlled as many of Burton’s were, in every sense. Control and order shaped the archive, too, and in this book I have argued that archival practices have been essential to photographic practice, both at the time photographs were made and in the decades since. To understand the role photography played in forming communities of knowledge and sustaining them over time, we have to take account of archival practices over time as well. Photographs exist as material objects, layered with the marks of their creation and circulation.76 Collected and categorized in institutional archives, they take on an evidentiary character that has been, as Stefanie Klamm observes, ‘defined by the actors within the archive (or the discipline) and their interests, who through the structuring and preparation of knowledge have control over social and cultural memory’.77 It is therefore in the care of archives, and the trajectories of photographs in and out of them, that we see disciplinary and institutional histories being made – and boy-kings with them. That much of this work was undertaken after the fact, and by invisible, uncredited workers, makes it no less significant. The significance of archival practices is all the greater, in fact, since it was in these overlooked or dormant-seeming periods that the colonial framework of knowledge production could bed down deep into the archive while the world outside tried, at least, to change.

Every archive has an external face, even if that face is rarely as public or as golden as Tutankhamun’s has been. The Tutankhamun photographs were taken with scientific ends in mind, from the way in which Carter folded, cut and filed prints with the object record cards, to the framing and cropping of photographs for different kinds of publication. But what constitutes science, as this book shows, depends on who is speaking for it. In the ten-year span of clearing, documenting and repairing objects from the tomb, the discourse of science and the visual possibilities of photography were often pulled together in accounts that Carter sanctioned or composed. Not to be able to see through such verbal and visual narratives reveals a weakness at the heart of Egyptology, which has primarily used its photographic archives as genealogical charts, rather than sites of self-examination and critique.78 Alternative archives may yet open other vantage points on the field’s own history, privileges and presumptions, and in doing so may encourage alternative forms of practice to arise within the field itself. There is work to do.

Albums, lantern slides, postcards, digitized newspapers, printed books. Negatives in more materials and sizes than I ever expected to encounter. Numbers and alphabetical lists that ran parallel for a while, only to cross each other and skip into other series entirely. I embarked on a study of the Tutankhamun photographic archive thinking that this most famous of finds, and most famous group of archaeological photographs, would make for a straightforward case study of how photography was used in interwar Egyptian archaeology. I thought the doors would be either open or shut, not pivoting back and forth almost a century after the vaunted discovery, as if we could not get enough of the breathless, almost titillating, moment of revelation. The visual memory that endures is thanks in part to the photographs that were taken at the time, but much more to the ways in which have they been deployed, cared for and repurposed ever since. Even in the age of digitization, the photographs are not immaterial but closely tied to the materiality of various photographic objects (negatives or positives), especially in the excavation archives. They exist within an archival ecosystem of catalogues, mounts, correspondence, meeting minutes and files, all of which I have drawn on for this study – and all of which have a very real physical presence demanding some kind of attention or inattention, however unacknowledged those forms of attention, or inattention, may be. Specific archival practices may change over time; apparent revolutions, like the digital, may occur. But if the underlying structures are undisturbed, unquestioned, there is no ‘turn’ in ways of doing, thinking and seeing that originated in archaeology’s colonial context. There is only a deep and well-worn track: an unrippled reflection.

The history of photography is a history of archives – and both are fundamental to history itself. If photography was, to Mace and Carter, ‘the most pressing need’ on site, it was a need that extended beyond the tomb and into the arenas of emerging Egyptian nationhood, declining imperial power and a Euro-American imaginary in which ancient Egypt was a forebear to the great civilizations of the West. A slightly awkward forebear, in some ways, but one that could not be trusted to the modern Middle East. Every photograph of Carter ‘supervising’ a porter, of a motor car or telephone line bringing ‘modernity’ to Luxor, or of a ‘refined and cultured’ mummified head, had that assumption at its heart, as much a part of photography as the f-stops on Burton’s lenses. There are eerie echoes of this salvage and salvation trope both in the 1970s Treasures of Tutankhamun tours, developed as they were on the back of UNESCO’s Nubian campaigns, and in the digital reproductions and online databases associated with the Tutankhamun archives today, which operate against the backdrop of heritage debates that too often take preservation and protection as a Western remit in which the residents of Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries must be trained.79

The history of the Tutankhamun archive shows that it is not the photographic image alone that has made the track between Egyptology’s colonial past and its present day. Rather, it is the materiality of the photographic objects, their archival lives and the information and ideas with which the archive has filed, labelled, numbered and stamped them. Archival practices carry traces of the knowledge communities, power structures and value systems in which photographs were created and used, as surely as the photographic image carries traces of what was in front of the camera at a given moment in time. New cataloguing, re-photography, scanning, conservation interventions: all such practices serve only to compound or mask the issues at stake if they are used without critical and historical awareness. Throughout its almost one hundred years of existence, the photographic archive of the Tutankhamun excavation has been ‘brought up to date’ or ‘made complete’ several times, and each instance has contributed to, even impelled, the normalization and sublimation of colonial knowledge formations and visualities. No matter how iconic an image may be – and many of the Tutankhamun photographs unquestionably are – we must look beyond the image and into the archive in order to confront the fact that photographs, like pharaohs, enjoy long afterlives.

1 ‘Tutankhamen’s third coffin – of solid gold: The uncovering’, Illustrated London News, 6 February 1926: 232.

2 The 18 × 24 cm negative (now TAA 1354) was among those sent to New York in 1948 when Charles Wilkinson cleared Carter’s house. Carter’s half-plate glass copy, GI neg. P0770 (here, Figure 7.1), was already in the Griffith Institute when Fox compiled her guide in 1951; hence it must have been in London before his death.

3 E.g. Carter, The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, vol. II, which includes other photographs of him, Callender and the ru’asa in the tomb, and compare Capart, Tout-ankh-amon; Fox, Tutankhamun’s Treasures.

4 Desroches-Noblecourt, Tutankhamen; Desroches-Noblecourt, Toutankhamon et son temps; and Cottrell, The Secrets of Tutankhamen.

5 See I.E.S. Edwards, Treasures of Tutankhamun; Gilbert (ed.), Treasures of Tutankhamun.

6 E.g. Allen, Tutankhamen’s Tomb, 56 (fig. 44; caption: ‘Carter examines the innermost gold coffin’); Collins and McNamara, 101 (digital colourization; caption ‘Howard Carter and an Egyptian assistant inspect Tutankhamun’s innermost coffin’); Reeves, Complete Tutankhamun, 109 (caption: ‘Carter patiently chips away at the hardened black unguents poured liberally over the innermost, gold coffin’).

7 See the last page of the press pack, available for download at http://www.itv.com/

8 Reid, ‘Remembering and forgetting Tutankhamun’; Reid, Contesting Antiquity, 51–79.

9 See http://www.nywf64.com/

10 On the Nubian temple campaign, see Carruthers, ‘Grounding ideologies’; Allais, ‘Integrities’.

11 This and other biographical details were recounted in her obituaries, e.g. Romero, ‘La mort de Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt’, Le Figaro, 24 June 2011; [unsigned], ‘Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt, première femme égyptologue, est morte’, Le Monde, 24 June 2011; and [unsigned], ‘Christiane Desroches Noblecourt’, The Daily Telegraph, 1 July 2011.

12 See Desroches-Noblecourt, Tutankhamen, vi (acknowledgements).

13 E.g. Desroches-Noblecourt, Tutankhamen, 137 (figs. 82–3), 138 (fig. 84).

14 Ibid., 164 (fig. 101).

15 MMA neg. TAA 1248, for which a film copy negative (P0792A) exists in the Griffith Institute, perhaps dating to the 1950s and thus available to Desroches-Noblecourt in her Oxford-based research.

16 Ibid., 165 (fig. 104).

17 Ibid., vi (acknowledgements). For the Petit Palais catalogue, different colour photographs (uncredited) were reproduced, with new monochrome photographs supplied by Mohammed Fathy Ibrahim, chief photographer for the Centre for Documentation. They are a mixture of whole-object and close-up photographs, either with a grey or black background, or against textured cloth: see Desroches-Noblecourt, ed., Toutankhamon et son temps, e.g. 94–7 (cat. 19, dagger 256k), 124–7 (cat. 26, chest 32).

18 I.E.S. Edwards, From the Pyramids to Tutankhamun, 282 describes Rainbird’s role in Kenett’s commissioning. For Kenett (né Cohen), see the brief biography at http://londonphotographicassociation.blogspot.co.uk/

19 Respectively, Desroches-Noblecourt, Tutankhamen, colour plate x (compare Gi neg. P0340); xv (printed in reverse; compare GI neg. P1258); and xxvi–xxvii (compare GI negs. P0512, P0512A; GI neg. P0166).

20 Edwards’ autobiographical account (From the Pyramids to Tutankhamun, esp. 247–65) obviously represents his own views and recollections, but is valuable for the perspective it gives on such organizational matters – and is supported by extensive records kept in the archives of the British Museum’s Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan. See also his introductory remarks and expressions of thanks, in I.E.S. Edwards, Treasures of Tutankhamun, 10–11.

21 Edwards, I.E.S. From the Pyramids to Tutankhamun, 266, 297. Philip Taverner, The Times’ marketing director, was also pressed into service on British Museum organizing committees: see his obituary [unsigned], The Times, 4 March 2016, and Edwards’ exhibition catalogue acknowledgements, cited above.

22 Ibid., 264.

23 Ibid., 263–4, 269.

24 ‘Power, majesty and detail in a memorable exhibition’, The Times, 29 March 1972, in a special supplement devoted to the exhibition.

25 See https://www.britishmuseum.org/

26 Edwards, From the Pyramids to Tutankhamun, 11.

27 The list of photographic credits in I.E.S. Edwards, Treasures of Tutankhamun, 54, does not easily convey whichphotographs originate with Burton photography from the 1920s; some are not Burton or Griffith Institute images(as in cat. 13), others are but are credited to a Cairo source (e.g. cat. 6). Of those photographs correctly creditedto the Griffith Institute, using Burton photographs, cats. 15, 16, and 18 (among others) are examples that have the background removed, and cats. 27 and 37 are examples with the background ‘greyed out’ or simplified.

28 Ibid., 45, based on GI neg. P0705.

29 Samuels, Theatres of Memory, 321–4, 337–47.

30 My discussion here draws on the insights of McAlister, ‘The common heritage of mankind’ and McAlister, Epic Encounters, 125–54. For the US version of the exhibition, from the perspectives of two people involved, see also I.E.S. Edwards, From the Pyramids to Tutankhamun, 314–18, and Hoving, Making the Mummies Dance, 401–14 (a self-aggrandizing account, but no less telling for that).

31 Hoving, Making the Mummies Dance, 402.

32 McAlister, Epic Encounters, 125–6.

33 Hoving, Making the Mummies Dance, 406–10.

34 Gilbert (ed.), Treasures of Tutankhamun, 2.

35 Ibid., 4.

36 Buckley, ‘The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb’, in ibid., 9–18. Hoving himself treated the 1920s dispute, and other controversies about the excavation, in his 1978 bestseller Tutankhamun: The Untold Story, but this appeared after Tutankhamun, and Carter’s heroism, were well-established in the museum presentations and public imagination of the discovery. Hoving’s book relayed Carter and Carnarvon’s until-then unacknowledged exploration before the ‘official opening’ in 1922, when they accessed the Burial Chamber and Treasury through a hole that Burton’s photographs afterwards helped hide (see Figure 1.2).

37 Gilbert (ed.), Treasures of Tutankhamun, 149 (cat. 38); 144–5 (cats 33–4), respectively.

38 Described in McAlister, Epic Encounters, 130–1.

39 See McAlister, Epic Encounters, 129, 133–40.

40 Carruthers, ‘Grounding ideologies’; for Cold War context, see also Carruthers, ‘Visualizing a monumental past’.

41 Advertisements, pp. 37 (The Museum Store, Modern Art Pavilion), 68 (Frederick & Nelson department store), 69 (J.K. Gill office supplies), in the Official Program, Treasures of Tutankhamun, published by The Weekly (‘Seattle’s newsmagazine’), summer 1978. The program’s centre spread (pp. 40–1) gives a scale layout of the exhibition, including the museum store.

42 Ashmolean Report (1952), 67.

43 Letter from Sewell to Walker, 1 July 1959 (GI/Carter 1947–7).

44 Ashmolean Report (1957), 75, 77.

45 For instance in a letter to the editor published in The Listener magazine, to follow up on an abridged radio interview he had given; reproduced in the issue of 17 March 1949: 450.

46 Ashmolean Report (1959), 71.

47 Ashmolean Report (1960), 78.

48 Ashmolean Report (1961), 77. The relevant photographs appear to be GI negs. P0540C, P0540D, P0540E, P0540F and P0837B, all 12 × 16 cm glass plates in the Griffith Institute. A former RAF photographer, Dudley joined the Ashmolean photographic studio as an assistant in 1956, was promoted to principal technician in 1968, and became its head in 1997, after Olive Godwin retired: see Dudley, ‘Chief photographers’. I am indebted to David Gowers in the current Ashmolean photographic studio for this reference and his own recollections.

49 Murray and Nuttall, Handlist; Desroches-Noblecourt, Tutankhamen.

50 Ashmolean Report (1963), 85.

51 Murray and Nuttall, Handlist, vii.

52 See list at http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/

53 Ashmolean Report (1971–2), 58.

54 Ashmolean Reports (1958), 81; (1963), 5; (1964), 85–6.

55 Ashmolean Report (1981–2), 50.

56 ‘Conservation of Carter negatives and prints’ report by Miss. A.C. Western, Chief Conservator, Department of Antiquities, 23 January 1980 (GI/Carter 1978–80).

57 Ashmolean Report (1983–4), 48.

58 Ashmolean Report (1984–5), 51. I warmly thank Elizabeth Fleming (née Miles) for sharing with me her memories and the rationale of the extensive work she did on the Tutankhamun photographs in the 1980s and 1990s.

59 Ashmolean Report (1988–9), 45.

60 See http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/

61 Allen, Tutankhamun’s Tomb, 7. The New York exhibition shared a title with Allen’s book, while the Chicago venue used the title ‘Wonderful Things! The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun: The Harry Burton Photographs’ (see https://oi.uchicago.edu/

62 See http://www.metmuseum.org/

63 See http://www.metmuseum.org/

64 The site is http://www.griffithinstituteprints.com/, in association with art print and frame making firm King and McGaw.

65 See http://www.factum-arte.com/

66 One example: http://www.premierexhibitions.com/

67 See http://www.sc-exhibitions.com/.

68 See http://www.sc-exhibitions.com/

69 At https://www.youtube.com/

70 Collins and McNamara, Discovering Tutankhamun.

71 GI negs. 1189, 1190; MMA negs. TAA 1157, 1158. Mounted in MMA/Albums, pp. 880f, g, h, i.

72 ‘Tutankhamen’s honorific orders: symbols of sun and moon’, Illustrated London News 23 April 1927: 726.

73 Including Rohl, A Test of Time, 93, and web coverage such as Sonny Stengle, ‘The mysteries of Qurna’ (http://www.touregypt.net/

74 David, Bei den Grabräubern, 198–200, 216–18. I thank Caroline Simpson and Kees Van Der Spek for pointing me to this book.

75 Photograph captioned ‘Egyptian students at Luxor’, The Times, 15 February 1923: 14; see Riggs, Tutankhamun: The Original Photographs, 96 (fig. 128).

76 See Klamm, ‘Reverse – Cardboard – Print’.

77 Ibid., 168.

78 See also Riggs, ‘Photographing Tutankhamun’.

79 During the week in which I finished writing this chapter, the Oriental Institute (OI) of the University of Chicago – founded by James Henry Breasted – launched a fundraising video ‘highlight[ing] the OI’s mission of discovery, preservation and the dissemination of knowledge’ in Egypt. The video emphasizes the ‘record’ created by the Epigraphic Survey’s photography and line drawings, the training offered to Egyptian conservation students (so that they can perform future ‘maintenance’ of OI repairs), and describes the OI’s Egyptian archaeological staff as ‘specialists’ because they use trowels and brushes – the most basic archaeological tools. Training activities are said to anticipate the day that ‘they’ don’t need ‘us’ anymore, ‘because there will be other countries where we need to work anyway’. ‘We are trying to teach people to value what they have, teaching them how to explore it’, a former director of the OI explains. This is one example of a common narrative refrain in the archaeology of the Middle East, and I single out the Oriental Institute here only because of the coincidence of the video’s publication and promotion through social media: see https://youtu.be/