Strategy, my boy, is a profound science, and don’t cost more

than two millions a day, while the money lasts.

—ROBERT NEWELL, UNION HUMORIST

ON FEBRUARY 11, 1861, Davis received word that the Confederate Provisional Government had unanimously elected him president two days before. “Oh God, spare me this responsibility,” he cried upon hearing the news. “I would love to head the army.” Previously, Mississippi had named him a major general, “the career suited to his taste,” and in a speech delivered the day he received word of being named president he had thanked Mississippi for the office and promised to take the war to the North—if war came. But duty called, and as historian Steven Woodworth aptly observes, “Jefferson Davis would never shirk his duty as he saw it.”1

Woodworth’s observation is critical. Davis’s sense of obligation drove him to accept the highest office in the Confederacy, placing him at the core of its strategy making. How Davis saw things would govern much of the way the Confederacy fought its war. Fundamental to this was Davis’s vision of what being president meant in regard to military matters. The Confederate constitution, like its U.S. model, designated the president commander in chief of the armed forces. Today, this is understood to mean that the president decides whether to use military force, where, for how long, and for what political purpose (within the strictures of the War Powers Act). Davis had a more expansive view of the president’s military prerogatives, one he spelled out before his elevation to the office: “If the provisional government gives to the chief executive such power as the Constitution gave to the President of the U.S. then he will be the source of military authority and may in emergency command the army in person.” In July 1861, Davis signed a letter to Lincoln, “Presdt. & Commander-in-Chief of the Army & Navy of the Confederate States of America,” a clear indication of what he saw as his task: leading the nation and the military.2 To Davis, the Confederate president was not only commander in chief; he was also general in chief, a view harking back to the Napoleonic example of the political leader who also led the army in the field. This refusal to separate the two in an era when industrialization and the increasing scale and power of the nation-state were making war a more complex endeavor, one requiring clearer divisions between civilian and military labor, hobbled the South’s war effort. Moreover, it also prevented the much-needed appointment of a Confederate general in chief until 1865, when it was too late. The Confederate Congress had passed such a law in 1862; Davis vetoed it, insisting that it undermined the president’s role as commander in chief of the army by allowing the general in chief to replace general officers appointed by the president. This was also one of the reasons for his May 1864 pocket veto of a bill to create an army general staff.3

Here is one of the driving and most problematic elements of Davis’s personality: his tendency toward legalism, sometimes stretching to pedantry. He enjoyed showing others not only how he was correct but also how they were wrong. Davis seemed to have at least some awareness of this, once remarking to his wife in a letter that he wished he could “learn to let people alone who snap at me.” Worse was Davis’s general difficulty communicating with the people of the Confederacy.4

Shortly after his inauguration, Davis conceded that the South faced an unequal military contest, but he also sought to overcome this imbalance. The inequality began on the population front. The 1860 census numbered the inhabitants of the eleven Confederate states at 9,103,332. Slaves made up 3,521,110, more than a third. The Union retained a population of 22,339,991. This included those in the critical border states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri as well as the District of Columbia and the New Mexico Territory, whose combined population was 3,305,557, including 432,586 slaves. There were 525,660 people in the Rocky Mountain and Pacific coast areas, but they contributed little to Union military strength.5

The South’s large slave population produced in many white Southerners a fear of slave unrest, particularly if the war went on for some time. On the other hand, in the early stages of the struggle, slavery enabled the South to mobilize a large percentage of its white manpower for its armed forces, as the slave population kept the economy going.6

The Confederacy was also outmatched industrially. In 1860, there were 128,300 industrial firms in the United States. The eleven states of the Confederacy had only 18,206, and these were generally small concerns. The value of the South’s industrial output was but 7.5 percent of the American total. The North’s agricultural production also outstripped the South’s. Additionally, Tennessee, the Confederacy’s meat-producing larder, lay not far from the frontier. Taking skilled men from their workbenches and putting them in the ranks further undermined the South’s limited industrial capacity. Moreover, there was no powder mill in the South, and the Confederacy had few stocks.7

The disparity in strength also carried over to railroads, one of the era’s indicators of industrial might. The Union had 22,085 miles of rails, the South only 8,541. Railroad personnel were generally Northerners with a distinct lack of enthusiasm for the Southern cause. Railroads—their locations as well as carrying capacity—heavily influenced the prosecution of the war. General William Tecumseh Sherman compared the value of rail and wagon transportation in his 1864 Atlanta campaign, using as a measure a single-track railroad running 160 cars of supplies a day for 100,000 men and 35,000 animals. He concluded that the campaign could not have been mounted without the railroad because to supply the aforementioned force would have required 36,000 wagons, each pulled by six mules (220,800 mules) and hauling two tons per day for 20 miles. This would have been impossible because of the condition of the area’s roads.8

River transport also proved key for both sides, particularly in the West. Railroads had to be guarded; rivers did not. Railroads had a limited capacity; only the number of vessels and the water level limited river transport. About 1,000 steamboats worked Western waterways when the war began. The Confederates took a few, though no one knows how many; the Union built hundreds. They provided invaluable logistical support. One 500-ton steamboat could carry enough matériel per trip to provide nearly two days’ supplies for 40,000 men and 18,000 animals.9

But the South was not without advantages, including the soldierly traditions of many of its people. Davis boasted that Southerners were “a military people … We are not less military because we have had no great standing armies. But perhaps we are the only people in the world where gentlemen go to a military academy who do not intend to follow the profession of arms.”10 This gave the South an unusually large percentage of its male population with basic military skills and training. They were also eager to serve. Nearly 80 percent of the adult white male population of the Confederacy between the ages of fifteen and forty would put on butternut or gray, an unprecedented scale of mobilization. This translated into nearly 900,000 of 1,140,000 men. The North still held the advantage in numbers, with 4,010,000 men between fifteen and forty, but a smaller percentage rallied to the colors. As many as 2.8 million men served in Union armies.11

Both the North and the South generally raised troops at the state level, which increased the rapidity by which they gathered forces. A local politician might muster a company of around 100 men and then offer the unit to the state’s governor, who would then send it to a camp of instruction where it would be combined with other companies to create a regiment. Junior and midgrade officers, particularly in the beginning of the war, were often elected. Both sides also drew upon local militias, but again the South’s percentages—if not numbers— were more impressive. So many men flocked to the colors that initially both sides had more volunteers than they could arm.12

The antagonists had to pay these volunteers as well as finance the war and manage their respective economies. While the Confederate dollar held its value during the war’s first two years, it did not thereafter. And officials refused to tax their population. The South raised approximately 1 percent of its funds via taxes, a smaller percentage than any other modern wartime government. The solution: print money, lots of it, backed by nothing except faith in a government that had been in existence not much longer than its currency. The result: rampant inflation that destroyed the economy. The figures for its sources of income up to October 1864 give a clear picture of Confederate finances: paper money, 60 percent; the sale of bonds, 30 percent; taxation, about 5 percent; miscellaneous, 5 percent. No one knows how much paper money eventually circulated in the Confederacy. The various states, municipalities, banks, corporations, and even individuals also printed notes. The Union did a much better job on the economic front. By the same month of 1864 it had derived only 13 percent of its income from paper money; bonds generated 62 percent, taxes accounted for 21 percent, and 4 percent came from other sources.13

BEFORE RESORTING TO THE SWORD, Davis’s government attempted to achieve its political objective of independence through peaceful means. On February 27, 1861, shortly before Lincoln’s inauguration, the Confederates dispatched former Georgia congressman Martin J. Crawford to Washington in an eventually forlorn effort to convince Buchanan to recognize the Confederacy before he left office, Davis having had word that Buchanan was willing to receive such a representative. Crawford found Washington overrun with large crowds hoping to catch a glimpse of the arriving Lincoln. Davis insisted later that these frightened Buchanan, who refused to see the Confederates.14 He gave Buchanan too much credit.

After Lincoln’s inauguration, John Forsyth, an Alabama newspaperman, and A. B. Roman, of Louisiana, joined Crawford. The trio sought an unofficial interview with Seward on March 11, 1861. Seward refused. They left a letter explaining that the Confederacy was de jure and de facto a nation and sought the establishment of amicable ties with the Union. Moreover, they also wanted Seward to set a date for presenting their credentials to Lincoln. Seward would have none of it, and delayed. Finally, in early April, a huffy Seward told them that the U.S. government would not recognize the Confederacy and that he saw “not a rightful and accomplished revolution and an independent nation … but rather a perversion of a temporary and partisan excitement.”15

Davis saw this as treachery. Moreover, Seward’s actions genuinely shocked him, a foolish and naive response.16 Davis’s representatives were there to prosecute a revolution against Seward’s government. It was Seward’s job to thwart them. Doing less would have meant he wasn’t doing his duty. Davis should have understood this.

SECURING THE NEW COUNTRY dominated the Confederacy’s actions in the chaotic and heady days following secession. Despite some high-flown rhetoric about taking the war to the North, the new nation’s leaders concentrated on guarding their territory. Davis endured persistent demands from governors and local grandees for troops. Initially, adopting a version of an inherited system, he divided the country into eight military departments, each of which had at least two districts. Soon, small detachments were stationed along the coast from Cape Henry, Virginia, to Galveston, Texas.17

Politically, Davis had no choice but to protect everything. He did not have the luxury of trading space for time, as George Washington had in the Revolutionary War. A successful defense of the Confederacy’s territorial holdings would prove that the Confederates had forged a nation, thereby helping the cause of recognition while also protecting the logistical support and recruiting base necessary for waging the war.18

The South also needed to maintain control over all of its territory because of its “peculiar institution”—slavery. Davis feared that once the Union army took over an area within the Confederacy, that area would then become useless to the South. The North would carry off the slaves, destroying the social structure and making that area unredeemable. A military strategy not founded on the preservation of the entire Confederacy, it was thought, would ultimately result in the destruction of the South, even if it won victories on the battlefield.19

The initial Confederate military strategy contained two defective elements. First, Davis supported the dispersal of forces for a cordon, or perimeter defense, leaving the South weak everywhere. Second, he established the aforementioned departmental system, meaning the division of the Confederacy into supposedly militarily self-supporting entities.20 This increased the dispersion and created an unnecessary and inefficient compartmentalization of forces—though, as we will see, this was not as injurious as some writers have argued. The number of departments and their limits were also constantly altered.

Many Southerners’ demands for a more aggressive, offensive strategy complicated Davis’s situation. Southern newspapers pushed as hard as their Yankee counterparts for a thrust at the enemy’s capital.21 Davis refused to take this path. The Confederacy lacked the strength. Moreover, an attack against the North could have injured the South’s struggle for international recognition by painting it as the aggressor.

Davis had a high view of his own military abilities. He had graduated from West Point with such future Confederate notables as Albert Sidney Johnston and Leonidas K. Polk, left Congress to serve in the Mexican War as a colonel of volunteers, and was secretary of war in the Franklin Pierce administration. Davis kept a tight grip on the nation’s war effort, especially the Confederate War Office, essentially functioning as his own secretary of war. Five such secretaries served him, but his interventions generally reduced them to glorified clerks. Davis also exhibited a tendency to get down into the military weeds, too often losing sight of the big picture. Indeed, it appears that he could not distinguish between the tactical and strategic levels of war, and made the mistake of thinking his tactical success at the Battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican War automatically translated into a larger realm. The Confederate system, leadership, and strategic environment all contributed to its eventual defeat, something we will see as our story unfolds.22

WHEN THE WAR BEGAN, many military and political leaders on both sides failed to realize it would become as much an economic struggle as a military one. This crowd included Davis. The Confederate president, like many of his Southern brethren, placed great weight on the power of “King Cotton” and its allure to the European powers. Davis and his advisors regarded the fiber’s pull as so strong that they could almost assume British and French recognition. The myth of King Cotton gripped Davis before the war began. In a February 1861 conversation, he insisted to a fellow railroad passenger that the South could achieve foreign recognition if it stopped the export of cotton for ninety days. His companion disagreed, whereupon Davis asked if the man would concur if it were six months. He still disagreed, telling Davis: “You must remember there is over one million of bales surplus now in the Liverpool warehouses.” The president replied that therefore nine months would do it. The man countered that even that wouldn’t suffice. “Well then,” Davis said, “we’ll give them twelve months—that must bring their affairs to a crisis.”23

Faith in the power of cotton and the foreign necessity of obtaining it made the Confederacy’s diplomatic and economic strategies inseparable. Inextricably entwined with the cotton issue was Davis’s only significant foreign policy objective: recognition of the Confederacy. He believed economic and military support would follow, thus guaranteeing Confederate independence. Moreover, Davis believed that British recognition alone would discourage the North from prosecuting the war, and that the Union would withdraw from the fight from a fear of British intervention. Abroad, Davis and his diplomats built an image of a Confederacy fighting not for slavery but for freedom. The effort enjoyed some success in France and Britain before the Emancipation Proclamation.24

Like Davis, much of the Southern populace believed that foreign nations could not live without Southern “staples,” meaning, of course, cotton. An unofficial embargo on cotton exports stemmed from this belief, much of it driven by local vigilance committees, or Committees of Public Safety, in Southern ports, though there were also supportive governors, such as Georgia’s Joseph E. Brown.25 The Confederate cabinet did not think an embargo the best means of influencing policy in European capitals, but it did nothing to hinder the movement.26 Davis opposed the cotton embargo and kept Congress from making it law. The Confederate government purchased the fiber for export, as well as to lay a foundation for internal credit at home to enable the purchase of overseas supplies.27 Officials such as Judah P. Benjamin stressed that the government had instituted no restrictions on exporting cotton, despite Union claims. Nonetheless, Davis never undertook any effort to make interference with the cotton trade illegal.28

The result of this chaotic policy on cotton was that the South failed to make effective use of its most valuable asset. The cotton crop of 1861 amounted to 4.5 million bales, worth $225 million in gold, almost ten times the value of all the gold in the South. Vice President Stephens proposed using $100 million in Confederate bonds to buy 2 million bales from both the 1860 and 1861 crops. They would then purchase fifty ironclad steamers to take the cotton to Europe, storing it until the price hit 50 cents per pound. He anticipated a profit of $800 million.29

This quixotic idea had a number of flaws, the most glaring being that there simply weren’t 2 million bales remaining from the 1860 crop. By the end of May 1861, about 3.6 million bales had already been exported to New England and Europe. By the time the Confederate government was fully organized, probably only a few hundred thousand remained. Moreover, getting the owners to part with the cotton for government bonds, obtaining Stephens’s fifty ships, and ensuring that the price of cotton climbed to 50 cents a pound when all knew that 4 million bales sat in storage were insurmountable obstacles. By the time the 1861 crop came in, the embargo and Union blockade were in place. The cotton could not be generally exported, and regular commerce had ceased.30

It took the Confederates until 1862 to realize that the Europeans were not willing to enter the war merely to regain a supply of cotton.31 After July 1, 1862, opposition to its export seems to have declined because its shipping volume increased.32 The Davis government took control of cotton exports in the war’s third year and began to press them. Doing so sooner might have given Confederate finance a surer footing.33 Davis’s administration never developed a comprehensive policy for the use of cotton. One million bales were shipped past the blockade, but another 2.5 million went up in smoke to keep them out of Union hands. An unknown number were smuggled out, traded to the enemy, or used by minor Confederate officials to meet government needs.34

Many others fell into Union possession and were sold.

In trying to use cotton as a tool of economic blackmail in exchange for recognition, the Confederates made a critical mistake. The impromptu embargo actually had the opposite of its intended effect: it discouraged British entry into the war.35 No Parliament could stomach the humiliation of bowing to what amounted to extortion. Moreover, politically, Britain found it beneficial to comply with a blockade that initially was not particularly effective. This could prove useful in a future conflict. And the British were dependent not only upon Confederate cotton but also upon Union grain.36 Davis’s belief in the lingering myth that King Cotton would encourage foreign intervention slowed Southern farmers’ shift from cotton to food crops.37 Clausewitz’s insistence that nations fight for political goals again proved correct.38 Politics trumps trade.

The right course would have been for the South to export its cotton as quickly as possible, before the blockade became firmly established, thus raising money for the war effort. But this had its own set of problems. The South lacked sufficient shipping and had to rely on foreign vessels coming to Confederate ports. This meant risking the blockade.39

Davis was correct in assuming that the lack of Southern cotton would damage Britain’s economy, particularly its textile industry. After British mills exhausted their accumulated stocks, tens of thousands of workers were turned out into the streets and reduced to poverty. The British government provided public relief on a massive scale. Further support for the stricken came from across the British Empire, as well as from Haiti and Japan. In December 1863, 180,000 Britons were receiving relief. This number dropped to 130,000 by December 1864. In spite of this, there was no cry for Southern recognition or British intervention. The industrial laborers of Lancashire and other areas detested slavery.40

Other economic forces conspired to prevent British recognition and intervention. By 1863, cotton was flowing from Egypt, Brazil, India, and the West Indies, while British and French munitions makers, iron and steel firms, manufacturers of wool and linen products, and producers of many other items did brisk business in war-related matériel. An increasing percentage of seaborne trade moved to the British flag, and for a short time blockade running became “one of the most profitable businesses in the world,” producing returns of up to 500 percent.41

Additionally, the working classes of Britain were not alone in loathing slavery. The growing British middle class also disdained it, and the Emancipation Proclamation brought that group firmly into the Union camp. The government, dominated by Lord Palmerston and John Russell, feared crossing this segment of the population, even with the advantage they enjoyed by virtue of the limitations on British suffrage, and in spite of their open sympathy for the South and its leaders. The French people also disliked slavery. Their favor fell on the North for that reason and also because they saw a strong American republic as a check on British power.42

Finally, Davis lessened the South’s chances of gaining European intervention by appointing two poorly chosen representatives: William L. Yancey to London and Pierre A. Rost to Paris. Yancey, a prominent politician and one of secession’s great “fire-eaters,” was a rough, gruff character unsuited to London’s diplomatic milieu. Rost lacked any prewar political fame, and his primary qualifications were French ancestry and a perceived mastery of French. The first made some influential Frenchmen wonder whether or not the South possessed native men of stature competent to represent its interests abroad, an impression no doubt confirmed by Rost’s poor grasp of the Gallic tongue. The pair accomplished very little. No European government officer would see them officially, and they spent most of their time protesting the blockade. Later Confederate diplomatic representatives, such as former Democratic congressman John Slidell, proved more effective, but there was only so much they could do.43

ONE INCIDENT EARLY IN THE WAR raised Southern hopes of European intervention. On November 8, 1861, Captain Charles Wilkes of the Union warship San Jacinto stopped the Royal Mail packet Trent and removed James M. Mason and the aforementioned John Slidell, the recently named Confederate replacements for Yancey and Rost. The angry British ordered 14,000 men to Canada, prepared the fleet for war, and demanded an apology, as well as the return of the prisoners. There is some suspicion that the two were dispatched as agents provocateurs whose arrest would provoke war between Britain and the Union. Their itinerary was widely publicized, and they had mingled with the crew of the San Jacinto in Havana, glibly discussing their intent. Lincoln replied with his famous “One war at a time” comment and placated the British by releasing the prisoners. This defused the situation, which was probably not as dangerous as many at the time believed. Britain had very little to gain, and much to lose, by going to war with the Union.44

Though this raised Southern hopes of foreign intervention, it remained little more than a “chimera,” as historian Russell Weigley pointed out. Lee, for one, held out no chance that the so-called Trent Affair would prove the South’s salvation, telling his wife not to count on war between the North and Britain. He predicted that if the Union leaders had to choose between war and freeing their captives, they would certainly let the men go. The South would have to win its independence alone, and it was capable of doing so. “But we must be patient,” Lee wrote. “It is not a light achievement & cannot be accomplished at once.”45

Despite Southern hopes and Northern fears, only during a short period in 1862 was British and French intervention even a possibility. After this, Union strength became increasingly apparent, and Union military forces had demonstrated progress. The French were keen to recognize the South—if the British went first. But the British refused to lead. Indeed, after the summer of 1862, even if the Europeans intervened, it was not likely that they could save the South. It would have required the assumption of commitments the European powers were unwilling to bear, while also threatening their possessions and economic interests in the Western Hemisphere.46 In the end, the decision to intervene was a matter of clear cost-benefit analysis. The cost of intervention was steep and promised little in return except for the chance to buy Southern cotton. To Britain, the cost simply outweighed what it could possibly gain.

DESPITE CONFEDERATE PRESSURE, the North refused to abandon a number of installations that Union troops held in parts of the South. Davis insisted that the South wanted peace, which it did, but it also wanted control of the entirety of the new Confederacy. The small concentrations of Northern troops in places stretching from Texas to the Key West forts angered Davis, as did a Union ship, Star of the West, trying to bring supplies to Fort Sumter. The continuing Union presence at Fort Sumter proved particularly galling, a thorn demanding removal.47 The Confederate effort to win control over these Union outposts in the South turned secession into civil war.

Most Southerners cheered the Confederacy’s bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, though not all believed it wise. Secretary of State Robert Toombs had warned of the consequences offiring on the fort, believing it would “inaugurate a civil war greater than any the world has yet seen… . You will wantonly strike a hornet’s nest which extends from the mountains to the oceans, and legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is unnecessary; it puts us in the wrong; it is fatal.” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that “the attack on Fort Sumter crystallized the North into a unit and the hope of mankind was saved.”48

Not only was Toombs correct regarding the effects of the bombardment, both immediate and long-term, he was also insightful regarding its futility. The South did not need to attack Sumter when it did, but its leaders believed they had no other choice. On April 6, Lincoln dispatched a messenger to inform South Carolina’s governor, Francis W. Pickens, that the Union would resupply Fort Sumter but not try to “throw in” men and matériel. Fearing that a lack of action would “revive Southern Unionism,” Davis, after consulting with his cabinet, decided the Federal presence had to go. Major Robert Anderson, the garrison’s commander, refused the initial demand to surrender, but remarked that he only had food for a few more days. This sparked more communication between the administration and Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, the Confederate military commander in Charleston. A Louisianan often referred to as the “Creole General,” Beauregard was in his early forties, small, energetic, and vain. A subsequent Confederate request for the date of Anderson’s capitulation followed, as well as an offer not to fire before then if the Union would take the same line. Anderson refused, realizing this would tie his hands in the event of the arrival of a relief expedition, but he committed to withdrawal by noon on April 15—unless he received new orders or more supplies. This didn’t assure the Rebels, who worried about the very resupply possibility Anderson raised. On April 12, 1861, at four-thirty in the morning, the Confederate guns opened on Sumter. Allowing the post to surrender without a shot being fired would not have produced the dramatic effect upon the North Emerson described.49

Deciding when to begin a war is crucial. Launching a conflict too early can be as fatal as launching one too late. The South went to war too early. The Confederacy should have suffered the indignity of the Yankees holding on to a small piece of South Carolina for a bit longer, exported their cotton through blockade-free ports, and used the money to import the needed myriad of weapons and military supplies. The Confederacy acted impetuously when patience would have helped it more—and suffered for it. They brought upon themselves a war for which they were unprepared while emboldening a reluctant foe. They ignited a Northern rage militaire when waiting might have made secession a fait accompli.

Many see in the handling of the Fort Sumter imbroglio the first glimmers of Lincoln’s genius. To support this some cite Lincoln’s remarks to Gustavus V. Fox, who became the first assistant secretary of the navy, about their assessment that trying to resupply the garrison would be to the nation’s benefit, even if it failed. Sending supplies to Sumter put the South in an awkward situation. In order to stop the delivery of provisions the Confederacy would have to fire on the boats ferrying supplies, thus making the South the aggressor. This is indeed probably what Lincoln expected to happen.50

The Confederates, though, chose to reduce the fort to prevent its resupply, taking the first bloody step in an even more violent and spectacular way. Davis insisted that he authorized the bombardment because he believed the Union intended to use the guns of both the fort and a supporting fleet against the Confederate besiegers. Part of Lincoln’s response came in the form of his April 15 proclamation calling for 75,000 volunteers to enforce the laws of the United States. Davis considered this a declaration of war (he was basically right) and issued his own call for volunteers as well as for privateers. Davis dispatched three commissioners empowered to seek recognition from, and make treaties of friendship and trade with, Belgium, Great Britain, France, and Russia. Davis also wanted emissaries sent to the nations south of the Confederacy. In the wake of Lincoln’s call for troops, four states in the upper South seceded and joined the Confederacy: Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and, most important, Virginia.51

On May 6, 1861, the Confederate Congress passed an act recognizing that a state of war existed between itself and the Union.52 Though in many measures inferior to the North, the Confederacy still possessed a solid strategic position: it had clear control over nearly all of the territories of the secessionist states, a clearly defined government, and a significant and growing army. Its position was a historical anomaly, as rebels usually have to fight to establish control over territory and governmental structures.53 The problem was, of course, that it had launched the war before it was strong enough to ensure that it could keep everything it held. It could not match its political ends with sufficient military means—and it never would. Significant as this was, it did not guarantee Confederate failure. The Union would have to uphold its end—or fail.

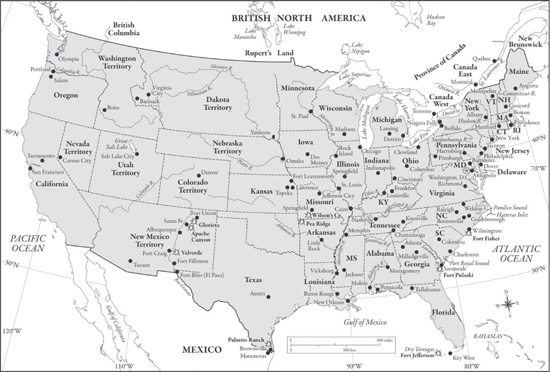

The United States during the Civil War. Adapted from Russell F. Weigley, A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861–1865 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), xxx.