George had been drinking in the pub with his friends for about twenty minutes when, from out of the smoke, Api pounced on him like a panther.

“Aren’t I good enough for your mates?” Api said.

George was taken aback. He hadn’t seen Api since they’d quarrelled at Te Huinga. “I don’t know what you mean,” he answered. “It’s good to see you, Api. Been a long time.”

Api laughed. Mocking. Scornful. “Well I’ve been sitting over there ever since you came in,” he said. “Watching you. You and your mates.” He jerked his head at the others at the table.

“I didn’t see you,” George answered.

“You didn’t want to,” Api said.

“So why didn’t you come over to me?” George flared. “Bit of a snob aren’t you?”

“I know when I’m not wanted,” Api answered.

George gave a gesture of helplessness. Api would never change. What was the use. All this suspicion. All this distrust. The wonder was that they were still friends.

He introduced Api to the others: Peter, Warren and David, all from the office where he worked. All members of the establishment that Api so despised. White collar. Middle class. The people climbing to the top. Elitist.

“I’ve seen you around,” David said. He put out his hand and Api gripped it in a test of strength. David gave a nervous smile.

Api filled his glass from a jug on the table. “Up the lot of you,” he saluted.

“Quit it, Api,” George said.

“And up you too, mate,” Peter interrupted. He had met Api before and their antipathy for each other was obvious. Polarised from the beginning by their different backgrounds neither would give an inch to the other. Their meetings had always been characterised by the clash of flint against flint.

Hastily, George separated them. “Look here you two,” he said. “I came in here to have a nice quiet drink. Now simmer down.” He started to make small talk with Warren. The atmosphere began to cool, relax and spread itself out comfortably as if a belt had been let out a couple of notches. George smiled at Api. While Warren was talking with Peter and David, he turned to Api and said:

“You know, it really is good to see you, Api.”

Api shrugged his shoulders. “What’s the celebration? It’s not like you to come to the pub, brother.”

“David’s been promoted,” George answered. “He’s leaving us at the end of the week.”

“And you?” Api asked. “You been promoted too?” There was a hint of derision in the words. Behind dark glasses Api’s eyes pricked George with ill-concealed mockery.

“No,” George answered.

“So you haven’t been sucked into the system,” Api said. “Not all the way yet.”

“They don’t want me,” George returned.

Apparently he still didn’t fit in, still appeared to lack that special sense of administrative ability and those nebulous qualities which interviewers were instructed to seek out in those applying for promotion. What the hell. He was happy enough where he was anyway.

“George should have been promoted though,” David said to Api with a quick, anxious smile.

At his words, Api exploded with anger. “Don’t you patronise us, man.”

“Api . . .” George began.

But once Api was started he was difficult to stop. His temper flashed out like a paw.

“Of course my brother should have been promoted,” he said. “But he’s a black man and this is a white system. And does the white man want us in positions of power? Like hell he does.”

“Hey, easy there,” Warren interrupted.

“Look,” David began. “I didn’t mean to . . .”

“No, you look,” Api growled, “You take a good hard look at the system you’ve created. It’s in your image, not ours. Everything about it is white. Religion. Education. Politics. You name it. And I’ll bet you there’s hardly any of us in it. Why? Because you’re scared of us. So you keep us down. At the bottom of the system. Eh. Eh.” The words cracked like breaking bones.

“Crap,” Peter muttered.

“What did you say?” Api asked dangerously.

“Forget it, Api,” George said. “Peter, just shut up won’t you? Both of you, drink up.”

But Peter took no notice. “I said crap and I mean crap,” he said again. “Just because you can’t cope with the system, Api, you accuse it of being racist.”

“Hell, that’s because it is,” Api answered.

“Prove it then,” Peter said.

Api began to laugh. His laughter rose above the hum of conversations in the pub, catching the attention of a few people in the crowded bar. Momentarily diverted, they watched Api curiously before returning to their drinking.

“What’s the joke?” Peter said angrily.

“You,” Api answered. “You ask for proof and there’s so much of it I don’t know where to begin.”

Because there isn’t any,” Peter said.

Api narrowed his eyes. Then he flashed the quick smile of a panther. “Who discovered New Zealand?” he asked.

“Eh? Oh, Abel Tasman,” Peter answered startled.

Api grinned with triumph. “Man,” he said. “Your answer is your proof. Long before Abel Tasman got here, Kupe discovered this country. But you’ve probably never heard of him, have you. After all, he was only a Maori.”

Peter reddened with anger. “Kupe? He’s just a legend.”

“Your second proof,” Api answered. “Anything that happened to us you call myth or legend. Anything that happened to you is called history. Cheers man. You better shut your mouth by drinking up.”

By now, Api was in a tremendous humour. He drained his glass and winked at George. Then he turned to Peter and said:

“How about buying us another round, friend?”

Peter looked at him with eyes gleaming. “Buy your own,” he said.

For a moment, George thought that Api would lash out with his fists. But no, Api was enjoying the extent of Peter’s antipathy.

“Don’t be like that,” Api mocked. “Buy your brother another drink.”

Api. Circling Peter with his calculated comments. Teasing. Trying to draw Peter further out into the open. Waiting.

“Lay off him,” George warned Api.

But it was too late. Peter had had enough. “You see racism in everything, don’t you?” he said to Api. “The system as you call it. Everything. And only because you haven’t been able to make it.”

“The system won’t let me,” Api taunted.

“Why not? Everybody goes through it. All of us must face it. But you? Oh no. You want to pull it down. Well you’ll never do it.”

Api’s eyelids flickered with growing anger.

“Yes,” Peter continued scornfully. “I’ve seen you and your friends down at Parliament. You’ve set up an embassy down there haven’t you? To protest for Maori rights, isn’t it? Well, there’s some of us who think you already have more rights than we have. And we all think your protest is a big laugh. A joke.”

“Come off it, Peter,” George said uneasily. “Api, don’t listen to him. It’s the beer talking.”

But Api was moving in for the kill. “You think you’re so superior,” he said to Peter. “Well, laugh while you can, man. The world won’t be yours much longer. Maori rights? Man, we’re protesting for human rights. And we want the white system to acknowledge our rights. We’re no joke, man. And we’re hitting you at the heart of your system. Parliament itself. Your home ground, man. And we’ll win too. You’ve raped us long enough.”

“For God’s sake, Api,” George said. “Enough of that talk.”

Api turned on him. “As for you, brother, whose side are you going to be on?”

“It’s not a question of taking sides,” George answered. “It’s not a matter of winning or losing.”

“So,” Api mocked. “Still sitting on that bloody fence. Come off it, brother. With me. Now.”

“You do things your way, Api,” George said. “I’ll do things my way.”

“How?” Api asked. “You’ll never get the chance. You’ll never be promoted. We can’t make it from the inside so we have to hit the system from the outside. Can’t you see that?”

George closed his eyes. When he opened them he saw Api putting down his glass. Api’s face was filled with contempt.

“Up the lot of you,” he said. Then he walked away. Silent. Padding out of the pub.

For a long time nobody spoke at the table. Then David and Warren began to relax. It was all over now.

“Well,” George sighed. He grinned at Peter.

“The black bastard,” Peter swore.

“Hey . . .” George began.

“The black bastard,” Peter swore again. “He’ll never win.”

The words punched into George’s mind. It wasn’t a question of winning or losing. It wasn’t a matter of white against black. It wasn’t a question of taking sides. Or was it? And if it was, which side was the winner and which side was the loser?

“Shut up, Peter,” George growled. “Shut up. And buy us another round, brother. Forget what’s happened. For God’s sake.”

Outside, the night grew dark. Don at Parliament, a tent had been pitched on the home ground. A banner flapped on a wooden fence: You Stole My Land Now Leave My Soul. From within the tent came the sound of a guitar, singing and laughter. The sounds did not seem aggressive at all. We’re protesting for human rights.

George stood watching from the shadows. He had been there over twenty minutes. Then he walked to the tent, past a placard bearing an upraised hand, and opened the flap. The light from a tilley lamp blazed upon him. He’ll never win, the black bastard, Peter had sworn. The guitar stopped. The people in the tent looked at him. Curious. Wary. In the corner was Api. George tried to smile.

“Api, aren’t I good enough for your mates,” he said.

‘Tent on the Home Ground’ was first published in Witi Ihimaera’s collection The New Net Goes Fishing (Heinemann, 1977).

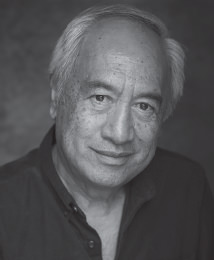

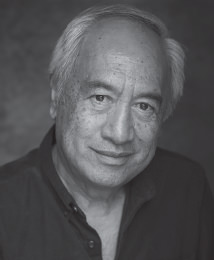

Witi Ihimaera is of Māori descent and is regarded as one of New Zealand’s leading writers. He was the first Māori writer to have a book of short stories and a novel published in the 1970s, and ‘Tent on the Home Ground’ is one of his earliest published stories. Since then he has written a number of important and award winning books including The Whale Rider, Bulibasha King of the Gypsies and Māori Boy. His latest book is Navigating the Stars. He lives in Auckland.