“Rollin Reineck’s Corner”

Colonel Rollin Reineck USAF (Ret.) was the lead navigator for a B-29 Group in the Pacific during World War II. His e-mails were very clearly written and his essay on the Elgen Long book,, “Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved,” contains a fuel analysis statement of the Earhart flight to Howland Island that ranks as one of the best. However, in his later years Rollin sided with the Irene Bolam factions causing a serious rift within the followers of the Amelia Earhart story. CLD

SUbj: Re: [earhart] [Fwd: Lockheed on Dump Valves]

Date: 9/2/01 @1:53:13 AM Central Daylight Time

From: Reineck 711

Carol, you and I agree totally that AE was northwest of the island. To do celestial navigation with just one celestial body, navigators do what is called “a single line of position landfall.” The idea is not to make a straightin approach, but divert to one side or the other of your destination about 100 miles out. This is to insure you know which side of the island you are on. In Noonan’s case (because of the position of the sun) he diverted about 10-15 degrees north of his course so he would be on a heading of about 65 degrees.

Now, when he took his sun lines, he could tell how fast he was going on his new course as they cut his course line at almost 90 degrees. They would be called speed lines.

Noonan took one of these speed lines and advanced it through his destination (Howland). He knew how fast he was going and how long it would take him to reach the advanced line. When his ETA was up, he turned to the right on his advanced speed line (157 degrees) as he knew he would be northwest of Howland.

His procedure was to follow the speed line until he found Howland, BUT, repeat BUT, when they turned right they were north of the cloud bank that was seen northwest of Howland. Now the dilemma: should AE fly through the clouds and not see the island or should she fly under the clouds at 1000 feet and try to spot the island in rain or low visibility. AE chose the latter altitude. “I am flying at 1000 feet.”

However, Noonan did not know how far north west he was, and in all probability he was farther northwest than he thought. When a reasonable time went by and no island, AE said “We should be on you but can’t see you.” They were still under the clouds with some rain. Had she only known that Howland was in the clear and so were all other quadrants clear, I’m sure she would have continued on her Heading of 157 degrees.

The problem was she didn’t know this, and after a reasonable time, when she still had four hours of reserve fuel left, she headed for her alternate which I believe was the Marshall Islands. First and foremost is because the top echelons of our government wanted her to do that (Baruch and Westover visited her in California). If she couldn’t find Howland they could come looking for her and do some much needed reconnaissance of the Marshalls.

Remember, we are still diplomatically friendly with Japan at this time. Yes, she had enough fuel to make it, especially departing from a position northwest of Howland. The proof is that she landed within the reefs at Mili atoll in the Marshall Islands.

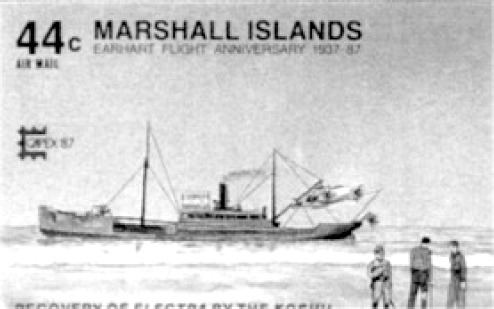

Earhart and Noonan being guarded by a Japanese Officer while the Electra is being hoisted on board a Japanese salvage ship presumably the Koshu

Subj: Re: [earhart) [Fwd: Lockheed on Dump Valves]

Date: 9/1/01 @1 :42:53 AM Central Daylight Time

From: Reineck711

Ron Reuther I feel your warning to Carol is unwarranted. “I would urge you to be very careful about your criticism of his (Long’s) book or his conclusions.” Researchers as well as anyone else have every right to criticize other researchers. That’s how we find the truth. In my critiques of the Long book, which I posted a few days ago, I take strong exception to Long’s conclusions.

There is no proof whatsoever that Earhart used greater power or flew faster than what Kelly Johnson advised and thusly used more fuel that made her ditch 50 to 100 miles short of Howland. If there is such proof, I’d like to see it. I went to the Air Force flying school (as a navigator in grade) in 1951. The technique that Long advances for increasing speed in high head wind areas was not taught at that time in either basic or advanced flying training. Who taught Earhart to use that procedure? It wasn’t Kelly Johnson as he gave her power settings to maintain 150 mph (130kts) TAS (true air speed) for the duration of the flight.

The correct position of Howland Island was known to the Coast Guard 10 months before Earhart departed. Even if Earhart didn’t have the latest charts, the new position could easily have been plotted on the chart she had or on any other map or chart Noonan was using. Does anyone think for one minute that the Coast Guard would have kept this information from Earhart when they gave it to the rest of the world as it was a hazard to navigation? The idea that it was classified is ludicrous.

The claim that Noonan could have crossed the sun shot with a moon shot to get a usable fix is equally ludicrous and shows a total lack of knowledge about celestial navigation. Let’s keep an open mind.

Photo of Rollin Reineck in World War II from the Paragon Agency, Book Publishers

“Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved,” Elgen Long,

Simon and Shuster Book Publishers

Critique by Colonel Rollin C Reineck, USAF (Ret).

Elgin Long concludes that Earhart ran out of fuel 20 hours and 34 minutes after she departed Lae, New Guinea, and ditched her airplane within 52 miles of Howland Island. In his book, Long contends that Earhart used more fuel than she had on board and ditched before she found Howland Island because she flew faster than planned to compensate for strong head winds. Long says, “The stronger the head wind the faster the plane must fly for maximum range.” The basis for this, Long says, is that for every head wind component there is a recommended speed for maximum range. However, increased speed means increased fuel consumption. Fortunately, Earhart was not taught this modern day concept of cruise control for maximum range. Earhart was taught (as were all pilots during WW II and years afterwards) that for maximum range the wing of the airplane must be in an attitude that will give maximum lift and minimum drag. This meant that there was an optimum speed to fly the airplane that would put the wing in that attitude.

For Earhart, Lockheed told her to fly the airplane at 150 MPH (130kts.) indicated air speed for maximum range, regardless of winds. If the forecast winds were too strong, postpone the flight. Long states in the PREFACE that the recent discovery of lost documents, THE CHATER REPORT (reproduced in the addendum of this book), has enabled him to solve the mystery of Amelia Earhart’s disappearance. Then he goes on to say that the radio transmissions, as found in the CHATER REPORT, “were not altered or shaded to change their original meaning.” Further, he took care not to inject “poetic license.” Let’s see if Long adheres to his principles.

The following are radio communications between Earhart and the Lae radio operator after Earhart took-off from Lae, New Guinea, at 10:00 hours, local Lae time which was 0000 GCT.

These radio communications are cited from the CHATER REPORT.

#1. |

At 2:18 PM (0418 GCT. 4 hrs, 18 min. after take-off) Earhart reported: HEIGHT 7000 FEET. SPEED 140 KNOTS. UNINTELLIGIBLE REMARK, EVERYTHING OKAY. |

It should be noted that Earhart’s (pilot’s compartment) airspeed indicator was not calibrated in knots, but in miles per hour. Accordingly, it seems logical that Noonan provided her with the figure “140 knots” and obviously meant it as GROUND SPEED. The bottom line for a navigator is COURSE and GROUND SPEED. They work in nautical mile, not statute miles. Long states that the 140 KNOTS (161 MPH) reported by Earhart was not her ground speed, but her true air speed (true air speed is indicated air speed corrected for altitude and outside air temperature). However, Long knows, as well as all pilots know, that when you give a position, you report the speed you are making over the ground, or GROUND SPEED, not TRUE AIR SPEED.

Long follows by saying “At four hours and eighteen minutes into the flight they were already experiencing stronger headwinds than anticipated. The stronger winds had made them recalculate their optimum speed” (for maximum range). Long’s interpretation of the 0418 GCT message is totally wrong.

Unfortunately, it is this mistake that is the foundation of the Long theory. What Earhart says is she is at 7000 feet and her speed is 140 KNOTS. It is more than obvious that Earhart is talking about GROUND SPEED when she says 140 KNOTS, not TRUE AIR SPEED as Long would like you to believe.

This means that instead of a head-wind, Earhart had a tailwind component for that period of the flight, which would be quite normal and expected flying in the intertropical convergence zone where winds tend to vary.

Long confirms his view “Noonan had navigated perfectly so far, they were exactly on course. A TRUE AIR SPEED of 161 MPH reduced by a 23 KNOT wind (26.5 MPH) would give them a GROUND SPEED of 134.5 MPH.” (See further in the report re: the 23 knot wind). Long says that if she maintains that TRUE AIR SPEED, fuel consumption will be excessive and she will have little if any fuel remaining when she arrives at Howland.

To prove his point about fuel consumption, Long prints a fuel analysis and says that Lockheed is the source citing a telegram March 11 and 13, 1937, regarding Earhart’s California to Hawaii flight. Long is misquoting the facts.

The information that Lockheed (Johnson) sent to Earhart on those dates is as follows:

THE POWER SETTINGS PROVIDED TO EARHART WOULD HAVE GIVEN HER A TRUE AIR SPEED OF APPROXIMATELY 150 MPH (130KTS). USING THESE POWER SETTINGS SHE COULD FLY FOR APPROXIMATELY 24 HOURS AND 10 MINUTES REGARDLESS OF THE WIND.

As you have noted, the power settings above are not the same as the power setting that appear in the Long book. Long has changed the power settings to strengthen his argument that Earhart used more fuel. Long contends that the airplane was much heavier at Lae than it was at Oakland, therefore, the power settings had to be increased. But that’s not true.

When Earhart left Oakland on 17 March 1937, there were four people on board each with personal luggage and parachutes. Also there was equipment and spare parts. In addition there was a trailing wire antenna with its motorized retrieval mechanism, 250 feet of wire and a lead weight in the rear of the plane. She had 947 gallons of fuel on board for take-off.

At Lae, there were on1y two people on board, no parachutes, and only enough personal things to be decent. Earhart and Noonan both discarded all unnecessary parts and equipment and personal belongings including books, charts, and even a hand gun.

There was 1100 (1092) gallons of fuel on board at take-off at Lae. This equates to 145 gallons more fuel at Lae than at Oakland. At six pounds per gallon this would equal 870 more pounds of fuel [on board the airplane at Lae vs. fuel load at Oakland]. However, because of the passenger load, parts and equipment, trailing wire antenna etc., the plane weighed only about 250 / 300 pounds more at Lae than at Oakland. Not enough difference to increase the power settings that were given to Earhart by Lockheed in March 1937.

#2. At 3:19 PM (0519 GCT 5 hrs, 19 min. after take-off) Earhart reported: HEIGHT 10000 FEET, POSITION 150.7 EAST, 7.3 SOUTH. CUMULUS CLOUDS, EVERYTHING OKAY.

Long states that this is “definitely NOT their position at 05:19 GCT.” He believes it was their position at 02:00 GCT as it was customary for mariners to give a noon position.

#3. At 5:18 PM (0718 GCT 7 hrs, 18 min. after take-off) Earhart reported: POSITION 4.33 SOUTH, 159.7 EAST. HEIGHT 8000 FEET OVER CUMULUS CLOUDS, WIND 23 KNOTS. (23 knots is 26.5 mph).

Again it is the navigator (Noonan) talking when Earhart gives the wind in knots. Doubtlessly a tail wind component that gave them the ground speed of 140 knots (161 mph).

Long says the geographical position is NOT where Earhart was at the time of the report, but he doesn’t know why. Although, Earhart gave NO DIRECTION for the wind, Long says it was a HEAD WIND of 26.5 MPH. How does Long know that? He doesn’t say.

The big question here is, DID LONG ADHERE TO HIS PRINCIPLES OF NOT ALTERING OR SHADING the radio transmissions as found in the CHATER REPORT? He changed GROUND SPEED to TRUE AIR SPEED. He said a wind reported was from a CERTAIN DIRECTION when in fact the radio communication DID NOT GIVE ANY DIRECTION. Long says that Earhart was NOT where she reported to be in two position reports that were given in the CHATER REPORT. Is this shading or is this deliberately changing the radio transmissions of the CHATER REPORT to support the author’s position?

Now, let’s turn to another assumption that is presented in the Long book. This assumption by Long says that Howland Island was miss-plotted. Long claims that Howland Island was actually six miles east of the plotted position on the charts that Noonan used and Noonan was unaware of the true position of Howland Island. Long is totally wrong.

In August of 1936, the Coast Guard vessel, the Itasca accurately plotted the Line Islands including Howland. It found that Howland was plotted 5½ miles west of its real position. Long would like one to believe that this information was CLASSIFIED and therefore not available to Earhart for her Pacific flight.

Ask yourself this question: If this island had been miss-plotted it would have been a hazard to navigation. The United States was not at war at that time and had no declared enemies; therefore, why would it be classified? There is no doubt that this information was made available to all mariners (Notice to Mariners) world-wide. It is inconceivable that Noonan would not have received the information that was discovered almost a year before the Earhart flight. The Coast Guard was fully aware of Earhart’s plans to fly around the world and to use Howland Island as a refueling stop. They were charged with providing whatever help they could to make the Earhart flight a success. Withholding such vital information is incomprehensible.

In a recent book about Amelia Earhart entitled, “East to the Dawn,” page 408, the author discusses this very point. Ms. Butler says: “The chart of the area then in use was #1198 (published by the hydrographic office within the Navy) and (contrary to the assertion that it showed Howland Island

wrongly placed) was in fact reasonably accurate. According to the last chart correction made by the U.S. Government dating from 1995, the coordinates to the beacon on the west side of Howland are: latitude 00 degrees 48 minutes north. longitude, 176 degrees 37 minutes west. The chart Fred was using showed Howland within half a mile of those coordinates. When years later, emulating Amelia’s world flight, Ann Pellegreno used the latitude and longitude that Fred Noonan had used for Howland. She found they were correct.”

Another erroneous assumption Long makes is that Noonan could “readily take additional celestial fixes if he needed or wanted them” even though Earhart was reporting partly cloudy weather conditions. There are only certain stars that can be used by a navigator to determine his position. The trick is to find those select stars. First, the star must be in the sky where you are flying. For instance, one can’t see the north star if he is at the equator, nor can he see the southern cross if he is in the northern latitudes. Secondly, the navigator must identify the star by associating with its constellation. As an example, the Big Dipper points to Arcturus. Without the Big Dipper, finding and properly identifying Arcturus is almost impossible. This same rationale would apply to any other star. It must be remembered that when Earhart left Miami, one of the windows that was to be used for celestial observations, had been covered over with aluminum. This meant that only the left window in the rear of the airplane was distortion free for celestial observations. When that limitation is coupled with partially cloudy conditions as reported by Earhart, taking any star shots would have been problematical at best. Noonan would have been very fortunate indeed if he had been able to obtain any celestial observations before dawn.

Long says that at early dawn, Noonan could have easily fixed their position by taking celestial observations of the sun and the moon. Most people are aware that the sun and the moon both rise in the east and set in the west. Even though both celestial bodies might have been observed by Noonan, he would have ended up with two parallel lines, not a fix.

Because of the partly cloudy conditions at night and the lack of adequate working conditions within the airplane for celestial navigation, it is very unlikely that Noonan was aware of his position at dawn within 75 miles. Accordingly, if he followed the standard navigational procedures, he would have made at least a 15 degree off-set correction to the left when they were about 100 miles out. This correction was made to insure that he knew which side of Howland Island he was on when he started on his final sunline course of 157 degrees.

Long is correct when he says that the sun shots taken by Noonan in the early morning hours would have provided a line of position with a 10 mile accuracy. However, Noonan had no idea where he was on that sunline. He could easily have been 200 miles northwest of Howland. When they made the right turn to a course of 157 degrees, Noonan and Earhart were both unaware how far they were from Howland Island. When the island didn’t appear in a reasonable time and no radio communications were received, they did the only thing that reasonable flyers would have done, they headed toward the Marshall Islands where there were some 1100 atolls and small islands to provide a safe haven. (There is evidence that they turned north when they couldn’t find Howland Island).

But what about the fuel? Long, by changing certain facts, using poor information and bad assumptions would have the reader believe that Earhart ran out of gas some 20 hours and 32 minutes after she left Lae, New Guinea.

The truth is that Earhart, maintaining a true airspeed of 150 MPH and using the power settings provided her by Lockheed, had over 24 hours of flying time ahead of her. When she called in at 1912 GCT, she had flown approximately 2556 miles (2200nms) at an average ground speed of 133 MPH. Maintaining a true airspeed of 150 MPH would mean that she had encountered an average head wind of 17 MPH.

At 2014, Earhart, in her last message said we are running north and south. At that time it can be reasonably assumed that she departed the Howland Island area and headed for the Marshall Islands. She would have had approximately 4 hours of fuel remaining. Using maximum range true airspeed of 150 MPH (130kts) and a tail wind of 17 MPH she would have been able to travel some 680 miles. Would it be enough to get her to the Marshall Islands? Yes, she did make it to Mili Atoll, the closest atoll in the Marshalls to Howland.

Subj: Re: Fwd: you haven’t got it straight-Carol

Date: 2/14/03 7:43:47 PM Central Standard Time

From: reineck711

To: Beardov@aol.com

Carol

Originally the Howland island coordinates were wrong, placing Howland about 5 miles from its correct position. However, a US Coast Guard vessel plotted the correct coordinates in August of 1936. That was almost a year before AE tried to find the island. Because it was so far off from the position (5 miles) on all maps, the Coast Guard doubtlessly put out a “Notice to Mariners” concerning the misplotted position. It was a hazard to navigation and it was the duty of the Coast Guard to warn the world what the hazard was.

Guess what Coast Guard vessel plotted the correct position in August of 1936. None other than the Itasca.

Clarence Williams, retired Navy commander, put together AE charts for the trip. Does it make sense to you to think he didn’t know of the change. Of course he did. Even if AE didn’t have a new chart with the correct posirion plotted, she or Noonan could have easily plotted it on a chart that they had.

All that said, it really didn’t make any difference as had they been within 5 miles, they would have easily seen the Island and the Itasca.

Just more garbage.

Rollin C. Reineck, Kailua, HI, Col. USAF Ret.

Rollin Reineck passed away in his home, peacefully, in 2007 at Kailua, Hawaii. He was greatly admired by those who knew him.