ON JUNE 20, 1632, when the charter for Maryland was signed and sealed, Cecil Calvert, although he lived in England, became lord proprietor of the Province of Maryland. Although Cecil had the right to set political and religious boundaries for Maryland, King Charles had the right to set its geographical boundaries. The charter partially describes Maryland as a peninsula surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the east, Chesapeake Bay on the west, and the Potomac River to the south. The colony’s northern boundary was described as that land “which lieth under the Fortieth Degree of Northern Latitude . . . where New England ends.”

At that time, King Charles I, the Calverts, and even English mapmakers had no specific knowledge of exactly which lands the fortieth degree of latitude crossed. Consequently, none of them had any idea of the huge fuss forty degrees north latitude would cause in the future.

George Alsop, an indentured servant in Maryland from 1648 to 1652, drew this map in 1666. It gave Europeans a tantalizing glimpse of the colonial frontier along Chesapeake Bay.

As lord proprietor, Cecil established Maryland on three foundations that he and his father believed to be crucial. The first — that colonists could acquire their own land — served a twofold purpose: it extended the English empire, and it gave the colonists property so they could increase their wealth. Loyalty to England and to the lord proprietor was the colony’s second foundation. The third foundation concerned religious boundaries.

Unlike England, Maryland would have no official established religion. To assure that religion would be a private matter, Cecil instituted a daring policy called liberty of conscience. Under this policy, as long as a colonist was loyal to the lord proprietor, no government positions would be withheld from him because of his religious beliefs. Nor would a colonist be granted any special privileges because of his or her religious beliefs. Liberty of conscience was an unheard-of freedom in seventeenth-century England. Yet as soon as Cecil’s colonists reached Maryland’s shores, they would have it.

In November 1633, two ships, the Ark and the Dove, containing about 140 colonists — a mixture of Catholics and Protestants — left England for Maryland. Cecil Calvert and his family, however, remained in England, where Cecil felt he could best defend Maryland’s charter from political rivals. Leonard Calvert, Cecil’s twenty-seven-year-old brother, was one of the colonists; Cecil had appointed him as the province’s first governor. Also on board were priests who belonged to the Catholic religious order known as the Society of Jesus, or, more simply, as the Jesuits. Led by Father Andrew White, the Jesuits were there to fulfill the charter’s mission of converting native inhabitants to Christianity. To avoid conflict with the Protestants, the priests paid their own way and were subject to the same conditions as the other free colonists on the voyage.

Cecil Calvert recognized the likelihood of religious tension between Catholic and Protestant colonists and sought to forestall it in a letter of instructions. In it, he directed Leonard and other officials “to preserve unity and peace amongst all the passengers on Shipp-board, and that they suffer no scandall nor offence to be given to any of the Protestants, whereby any just complaint may heereafter be made, by them, in Virginia or in England.” He requested that all observance of the Catholic religion “be done as privately as may be.” Furthermore, Catholic colonists were not to discuss or debate religion, and government officials were to “treate the Protestants with as much mildness and favor as Justice will permitt.”

The Maryland Dove is a replica of a seventeenth-century merchant ship. She is named after the Dove, which carried supplies to Maryland in 1634.

In early March 1634, three months after leaving England, the Ark and the Dove sailed into Chesapeake Bay, described by Father White as “the most delightfull water I ever saw.”

While the waters of the bay delighted the colonists, the first view of their new neighbors may have worried them. Father White noted, “At our first comeing we found . . . the king of Pascatoway had drawne together 500 bowmen, great fires were made by night over all the Country.” As Native Americans observed the Ark and the Dove, they felt a similar unease. News that the English “came in a Canow as bigg as an Iland, with so many men, as trees were in a wood, with great terrour unto them all” quickly spread among native villages. Neither group knew what to expect.

The Ark and the Dove sailed up the Potomac River and landed at Saint Clements Island, where officials erected a cross and claimed the land. Later, accompanied by an interpreter, Leonard Calvert journeyed farther inland and met with the leader of the Pascatoways, who according to Father White “gave leave to us to sett downe where we pleased.”

The colonists chose a settlement site along the Saint Mary’s River, near the mouth of the Potomac. They traded “axes, hoes, cloth and hatchets” with the Yaocomico Indians in exchange for a large parcel of land along the river’s shore. For several months, the Yaocomico people and the English colonists shared the site, which the English named Saint Mary’s City. This site and the Virginia colony’s Jamestown were the only two English towns in the Chesapeake Bay area.

Yaocomico homes and storehouses were constructed of frames of bent saplings, which were then covered with mats made of wetland reeds called phragmites.

Slowly, Maryland gained a toehold in America. Managing the colony long-distance, Cecil assigned manor lands to a select group of his colonists, who either paid for the land outright or rented it. They tendered part of every crop to the lord proprietor. In ten years, the colony’s population grew to between five and six hundred settlers.

Life in Maryland wasn’t easy. Building and sustaining a colonial homestead meant that everyone, even the wealthy, worked. Additionally, tobacco is a labor-intensive crop. All planters who could afford to hired help, mostly males. From 1634 to 1635, men outnumbered women six to one. During the second half of the seventeenth century, as other types of labor increased and as families were established, the ratio dropped to three to one.

ALTHOUGH SOME FAMILIES immigrated to the new colony of Maryland, most colonists were individuals seeking prosperous lives. Most of the early immigrants could not read or write. But public documents such as court records, wills, and estate inventories provide records of their lives. During the first half of the seventeenth century, the majority of Maryland’s workforce came from England as indentured servants enticed to the colony with the promise of fifty acres of land at the end of their indenture. These people signed a legal document called an indenture, in which they agreed to work for a landowner (called the master) for a specific length of time, usually four to five years. In return, the master paid the servant’s passage to Maryland and fed and housed him or her during the period of indenture. A master could sell an indenture to a third party if he or she so desired. The majority of indentured servants were seventeen to twenty-eight years old.

While most of the servants were English, some were African. During the first half of the seventeenth century, the English did not commonly use the term slave. All African and European workers, regardless of legal status, were called servants. In seventeenth-century English America, slavery was not hereditary, nor was it always a lifetime condition. A predetermined time limit could be set, although the term was often so long as to make freedom unlikely. Most of the Africans were slaves, but some were freemen. Others served as indentured servants for the term of their indenture and were then free of further obligation to the landowner.

As much as Cecil Calvert wished he could go to Maryland, he felt that he could best protect his colony’s boundaries, both geographical and religious, by remaining in England, where he lobbied endlessly on Maryland’s behalf. Leonard’s regular reports kept Cecil abreast of operations in the colony. While tobacco was Maryland’s chief cash crop, Cecil requested that Leonard also send goods such as timber and animal hides. Sometimes, though, his requests went unfulfilled. In April 1638, Leonard regretfully wrote, “The cedar you writt for . . . I could not procure to send this yeare by reason there is very few to be fownd that are usefull tymber trees.” Ships loaded with trade goods regularly sailed between America and England.

While wild animals — such as wolves, bears, and mountain lions — roamed Maryland’s forests, domesticated animals, specifically hogs and cattle, also posed a threat to a colonist’s survival, as they could wreak havoc on crucial food crops. The solution? Fences — although, in contrast to modern fencing practices, Marylanders enclosed their gardens rather than their livestock. Loose pigs and cows fended for themselves in the countryside. Colonists notched the animals’ ears in different patterns to indicate individual ownership.

Colonists protected their crops by weaving branches to form wattle fences that were pig-tight, horse-high, and bull-strong. The fence in the background is constructed with split rails.

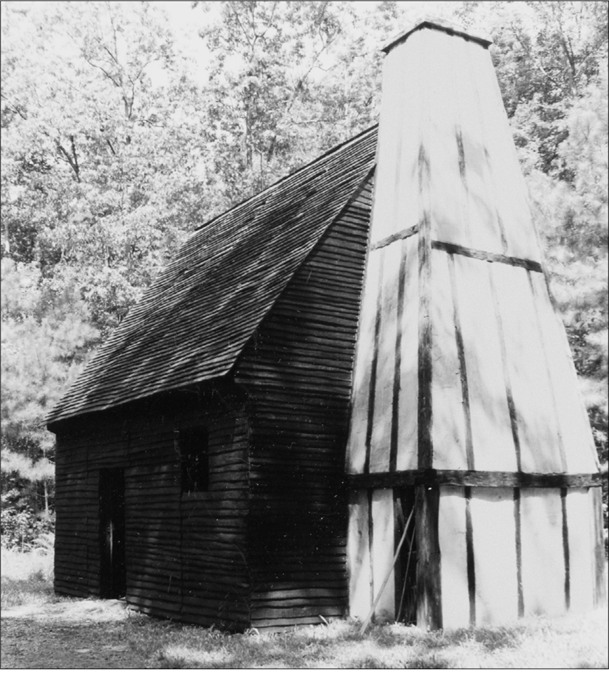

This replica of a seventeenth-century Maryland tenant farmer’s home is located in Saint Mary’s City. Its walls and roof are covered in clapboard, and it has a loft for storage and sleeping. The chimney is made of wattle and daub.

Acre by acre, Marylanders carved their place in America. And perhaps most important to Cecil Calvert, Catholics worshipped openly in Saint Mary’s City, fulfilling the dream of liberty of conscience that his father and he had shared. However, religious tensions between Protestant and Catholic Marylanders grew. Some Protestants worried that the Jesuit priests who were preaching in Indian villages might turn the native inhabitants against the Protestants. Maryland’s Protestants and Catholics argued about ongoing disagreements in England between the king and Parliament. Colonists grumbled about some of Lord Baltimore’s policies concerning land grants in the province. Gradually, these tensions began to threaten the very survival of the province’s unique policy.

DEATH WAS NO STRANGER to Maryland’s colonists. Swampy conditions and impure water caused fevers and diseases, such as dysentery, that killed many immigrants within weeks of their arrival. Changes in climate and diet, plus a harsh work routine, led to more deaths. Those who survived this period, which the colonists called the “seasoning time,” could expect a hard life. Seventy percent of the men died before age fifty. Women had an even shorter life span. Twenty-five percent of the babies died during their first year, and half of those who survived infancy died before they reached the age of twenty. Most children lost at least one parent. Step and half brothers and sisters became very common due to the remarriage of the surviving parent. And the court assigned orphans without relatives to new families, for whom they worked in return for room and board.

Troubled times in Maryland reflected troubled times in England. In London, conflict reigned between King Charles I and Parliament. Believing his right to rule came directly from God, King Charles claimed that he alone was best qualified to make important governmental decisions. Many members of Parliament, including a group of Protestants called Puritans, disagreed with this assertion and with some of the king’s religious and political policies. The Puritans also disapproved of plays, music, and dance, all pastimes loved by Queen Henrietta Maria (a Catholic) and the king.

As Parliament sought reform in politics and in the Anglican Church, the gulf between it and the king widened. Three times, King Charles I angrily dissolved Parliament and ruled England himself. When he finally reinstated Parliament, in 1640, general battle lines for a civil war were already drawn: Puritans, merchants, and the Royal Navy supported Parliament; the aristocracy, the Anglican Church, peasants, and Catholics supported the king.

Fearing for their safety, Charles and the royal family left London in January 1642 under the protection of Royalist troops. Oliver Cromwell, a Puritan and a very powerful member of Parliament, remained in London, where he served as a commander of parliamentary forces.

In 1644, as England’s civil war intensified, Cecil Calvert, perpetually strapped for cash, busily juggled the governing of Maryland even as he safeguarded his family’s safety and position in England. That same year, William Penn was born in London. Less than forty years later, he would seriously threaten the Calvert family’s boundaries in America.