EVEN THOUGH forty-nine years had passed since George Calvert had received his charter, the exact location of the fortieth degree north parallel of latitude remained unknown. This vagueness had not, however, prevented Kings Charles I and II from using the parallel to establish a more-than-two-hundred-mile-long boundary line. When the Calverts had first settled in Maryland, this wasn’t a problem: there was a lot of land and few colonists. By 1681, the situation had changed. A steady stream of new settlers established homesteads in the wilderness areas of both colonies, even in places where the boundary line was unclear. Both William Penn and Charles Calvert authorized land grants according to their perceptions of the line’s location. The colonists who bought these lands in good faith felt the squeeze when officials from both provinces requested tax payments. And each colony had its own laws and regulations. Which colony’s laws should the colonists living in the border area follow? The stage was set for some spectacular feuds.

The two lords proprietors expressed boundary concerns as early as April 10, 1681, when William Penn wrote to Charles Calvert. Writing he was a “strainger in the affaires of the Country,” Penn asked Calvert to give Penn’s representative all the help he could with regard to “the business of the bounds” and “observing our just limitts” so they could have a “Just & friendly” relationship.

Five months later, Penn wrote to six prominent planters who lived in the counties that bordered the northern reach of Chesapeake Bay. In preparing the letter, Penn consulted a map he had published and distributed — on which he had erroneously placed the fortieth parallel about fifty miles too far south, to include the city of Baltimore. Penn’s letter cautioned the planters that as they lived within what he believed were the boundaries of Pennsylvania, none of them ought to “pay any more taxes or assessments by any order or law of Maryland.” This news upset the planters, who unquestionably identified themselves as Marylanders. But some of them obeyed Penn’s order and stopped paying taxes to Maryland. This threat to property and income alarmed and angered Charles Calvert. Meetings among provincial representatives and letters sent to various officials left the situation unresolved.

In December 1682, Penn traveled to Maryland, where he and Calvert met for the first time. Penn had realized that his interpretation of the boundary line was incorrect, but as no one knew by what amount, he wasn’t ready to give up. In order to export Pennsylvania’s resources overseas, he needed direct access to major waterways. Trade would be severely restricted without Chesapeake Bay and the mouth of the Susquehanna River under his control, so Penn offered to buy some of that land from Calvert. The meeting ended with no resolution other than a promise to meet again sometime in 1683.

In the following years, matters only got worse. Citing confusion over the definition of “unsettled land,” Calvert claimed that per the charter granted his family by King Charles I, the Three Lower Counties belonged to him. In 1684, concerned about the feud’s outcome, Penn returned to England, where he could better defend his legal right to ownership. Calvert soon did likewise.

Despite the Decree of 1685, an act by the British Board of Trade and Foreign Plantations that attempted to settle the boundary issues, dissension continued for decades. In 1689, after a revolution in England, the royal charter for Maryland was withdrawn from Charles Calvert. England’s new king, William III, took control of the colony. The boundary issue did not improve in the early 1700s. After Calvert died, in 1715, his son and heir, Benedict, the fourth Lord Baltimore, renounced Roman Catholicism, joined the Anglican Church, and petitioned King William, a Protestant, for the return of the Maryland charter. Benedict died two months after his father, so did not live to see his petition granted. But the king did restore the charter for Maryland to Benedict’s son, fifteen-year-old Charles, who became the fifth Lord Baltimore. Born in England, this new Charles, grandson of the first Charles Calvert, had never seen Maryland.

Meanwhile, William Penn, severely in debt, unsuccessfully attempted to sell Pennsylvania back to the crown. He suffered a mild stroke in 1712; a second and then a third, yet more severe, stroke followed within the next year. Subsequently weak and incapacitated, William slowly declined and passed away in 1718.

In 1732, Charles Calvert, fifth Lord Baltimore, met in England with William Penn’s sons Richard, John, and Thomas, the new proprietors of Pennsylvania. The four men signed an agreement for a formal survey of the boundary lines. The survey would essentially follow the boundary lines as outlined in the Decree of 1685. The peninsula containing the Three Lower Counties would be divided in half equally by a north-south boundary that extended south to Cape Henlopen. The northern boundary of the Three Lower Counties was defined by a circle with a twelve-mile radius centered on New Castle, though the precise center point was still undetermined. The northern boundary of Maryland, formerly defined as lying along the latitude 40 degrees north, would now be defined as lying along the parallel of latitude that lay fifteen miles south of Philadelphia. When he signed the 1732 agreement, Charles Calvert, who was unfamiliar with the territory until he visited Maryland later that year, mistakenly ceded to the Penns all the territory that their father, William, had claimed back in 1681 — nearly two thousand square miles. Charles was not happy when he discovered his error.

Despite the agreement, no formal survey took place. Maryland officials continually enticed colonists to settle in uncertain territory as Marylanders. Consequently, mistaken perceptions of land ownership led to ongoing disputes between Maryland and Pennsylvania colonists who lived near the boundary lines in question. Two Pennsylvanian officials, John Wright and Samuel Blunston, expressed their confusion in a letter to Pennsylvania’s governor, Patrick Gordon:

But as the Line between the two Provinces was not Known, no Authority was claimed over those few Families settled . . . by or under Pretence of Maryland Rights, but they remained (by us) undisturbed, tho’ many Inhabitants of Pennsylvania lived some Miles to the Southward of them.

Settlers and officials were baffled. And still the Penns and Lord Baltimore dragged their feet.

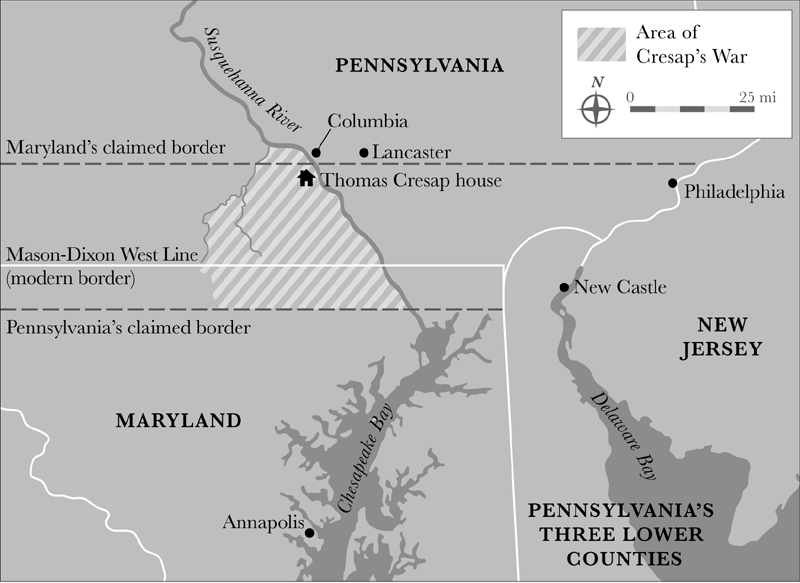

Unclear boundaries led to conflict and even violence. The most infamous dispute became known as Cresap’s War. White lines represent modern state boundaries.

The most infamous boundary dispute was the long-running battle between Marylander Thomas Cresap and his Pennsylvanian neighbors. When Cresap arrived in Maryland as a teenager in about 1717, he intended to buy land. Unfortunately, his debts piled up faster than his riches. To escape his debts, Cresap fled to Virginia, where he got married and lived on a rented farm. By 1729, the Cresaps had returned to Maryland and, considering themselves Marylanders, purchased land along the Susquehanna River. Their homestead lay along the 40 degrees north line of latitude, near modern-day Columbia, about eighty miles west of Philadelphia. Cresap couldn’t have picked a more troublesome spot.

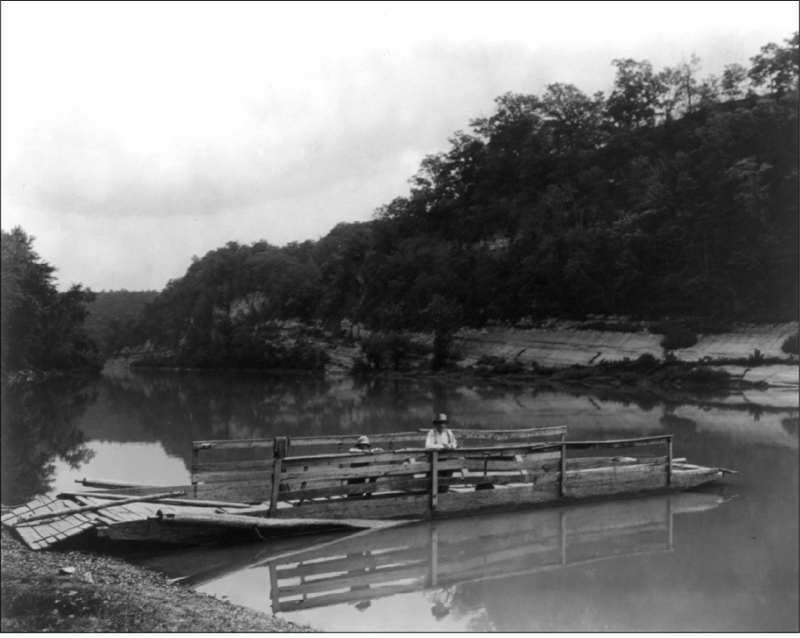

Cresap’s boundary trouble started with horses. Pennsylvanian-owned horses knocked down Marylanders’ fences and trampled their corn. More trouble occurred when three Pennsylvanians boarded Cresap’s ferry and, midway across the Susquehanna River, drew their guns on Cresap. As Cresap pulled in his oar, one of the men hit him with a gun and threw him overboard. Cresap swam to an island, from which he was later rescued. In his formal complaint, Cresap declared himself a Marylander and a tenant of Lord Baltimore. Later testimony would reveal that the Pennsylvanians actually had an issue with Cresap’s workman, but the dispute played into ongoing boundary-line tensions.

In 1732, Pennsylvanians alleged that Cresap and the Maryland militia had burned the homes of friendly Indians and unlawfully imprisoned them. When Pennsylvania’s governor complained, Maryland’s governor simply informed Cresap that “so long as he behaves himself well, he shall be protected from any Insults of the Pennsylvanians; and that it is the best Method for him to live in Peace and Friendship with the Indians.”

Thomas Cresap carried people and livestock across the Susquehanna River on a ferry similar to this one.

Later that year, Pennsylvania traders claimed Marylanders killed several of their packhorses. One man testified that Cresap had admitted to him that he had done the killing because “he lived in the Jurisdiction of Maryland, and that said [Pennsylvanian] horses had no right to be there.”

In retaliation for the incident, a group of Pennsylvanians rode to Marylander John Lowe’s home and accused him of killing their horses. They dragged Lowe onto the frozen Susquehanna River, saying he would be brought to justice in the Province of Pennsylvania. Eyewitness Cresap shouted, “If the Lord Baltimore would not Protect them in their Rights and land, They the [Maryland] Inhabitants . . . must apply to the King.” Cresap testified that a Pennsylvanian replied that “they have no Business with the King nor the King with them for Penn was their King.”

An angry Lord Baltimore issued a proclamation charging ten men, all of whom were allegedly “being or pretending to be Inhabitants of Pensylvania,” with storming Lowe’s plantation in a “Riotous manner Armed with Offensive and Defensive Weapons,” beating Lowe, his wife, and his children, and imprisoning Lowe and his sons. Lord Baltimore offered a reward of “Ten pounds Current Money of this our Province” for each man who was caught and convicted.

Unbelievably, the situation worsened. On January 29, 1733, Cresap’s wife, Hannah, and a group of Cresap’s tenant farmers were preparing logs to build a house and a boat. Mounted Pennsylvanian officials arrived at the site — one of the land parcels under boundary dispute — and arrested eight of Cresap’s workers. Her horse at a gallop, Hannah raced home to warn her husband.

At seven o’clock that evening, hoofbeats approached the Cresaps’ house. Worried, the Cresaps and seven or eight friends barricaded the door with benches. Two men knocked and requested a place to sleep. Cresap refused and threatened to shoot if they didn’t leave. The men replied that they had come to arrest him. Pennsylvanian Knoles Daunt tried to force open the door. Cresap poked the barrel of his gun under the bottom of the door and pulled the trigger, wounding Daunt. The Pennsylvanians fled, carrying Daunt with them. He died several days later.

Pennsylvania’s governor insisted that Cresap be tried for murder. However, the trial was held in a Maryland court. The jury concluded that Cresap, provoked and fearful for the safety of his family, had been justified in his action and was therefore acquitted.

And still the trouble escalated. In March 1735, Cresap testified that he had reliable information that Pennsylvanian officials “have offered large Rewards to several Persons to take this Deponent [Cresap] either dead or alive, and to set his . . . house on fire.”

A few months later, John Wright, a Pennsylvanian justice of the peace, stated that Cresap “came with about twenty Persons, Men, Women & Lads, armed with Guns, Swords & Pistols & Blunderbusses & Drum beating” to his land while he was peaceably harvesting his wheat. Wright swore that Cresap and his group had brought empty wagons with the intention of stealing the grain from his field.

The powder keg between Cresap and the Pennsylvanians exploded on November 23, 1736. As midnight approached, Samuel Smith, the sheriff of Lancaster County, and twenty-four Pennsylvanians “armed with guns, pistols, and swords” surrounded Cresap’s home. The sheriff read out a warrant for Cresap’s arrest, charging him with the murder of Knoles Daunt and various other “high Crimes & Misdemeanors” against Pennsylvanians. The sheriff demanded his surrender, saying that “they would not depart . . . until they had [Cresap] dead or alive.” The Pennsylvanian posse reported that in response to their declaration, Cresap cussed, called the people of Pennsylvania “Quakeing Dogs & Rogues,” and vowed to fight rather than surrender. According to Cresap, his terrified wife, Hannah, “who was very big with child . . . fell in Labor with the Fright.”

Much of the next day, shouts and shots peppered the air. Finally, the Pennsylvanians tossed firebrands onto Cresap’s roof. Fearing his family would be burned alive, Cresap insisted that Hannah — still in labor — and the children leave while he and the men remained behind. Flames soon engulfed the house, forcing Cresap and the other men out. More gunfire left one man dead and two men, including Cresap, wounded.

Under arrest and surrounded by angry officials, Cresap taunted his captors. As they entered the city of Philadelphia, he turned to a member of the posse and said, “This is one of the Prettyest Towns in Maryland.” Cresap was more correct than the furious posse knew. Philadelphia, at latitude 39°57′ N, is south of the fortieth parallel. According to Lord Baltimore’s royal charter, the city was in Maryland.

Cresap remained in jail for several months. After his release, he moved farther west, where he continued to play an important role in the European settlement of Maryland.

Although everyone clamored for clarity, nothing concrete was done to resolve the boundary-line issues. In 1735, King George II, disgusted with the situation, ordered England’s Court of Chancery, which handled cases regarding property and land, to settle the matter. Even as the case dragged on, the two provinces awarded new land grants in disputed territories despite the king’s order against it. They further ignored the king’s command that “the Governors of the respective Provinces of Maryland & Pensylvania . . . Do not upon pain of incurring his Majestys highest Displeasure permit or Suffer any Tumults, Riots, or other Outrageous Disorders to be Committed on the Borders of their respective Provinces.” Exasperated, Pennsylvania’s governor, Patrick Gordon, commented to Maryland’s governor, Samuel Ogle, “Nothing is more certain, than that the two Provinces, what ever Jangling there may be about it, must necessarily bound on each other, & have some Limits fixed, unless we are perpetually to quarrell.”

Finally, in 1750, fifteen years after the case — which had become known as the Great Chancery Suit — was filed, Lord Justice Hardwicke declared a verdict. The boundaries as outlined in the 1732 agreement would stand. The Penns and Charles Calvert had no choice but to agree. Each province appointed several men to a joint boundary-line commission.

As a group, the boundary commissioners agreed that the belfry of the courthouse in New Castle would be the center point for the circle with the twelve-mile radius to be drawn around that city. The commissioners hired local surveyors (some from each colony) and supplied them with instructions and provisions. They directed the surveyors to report their progress to the commissioners regularly. Commissioners from both provinces attended meetings, sometimes at specific sites on the line when disputes over placement arose and sometimes when boundary stones were being placed, to make sure their respective provinces did not get cheated.

THE LORDS PROPRIETORS commissioned, in writing, seven men from each province to serve as their representatives during the boundary-line survey. These commissioners directed the surveyors hired to run the boundary line and managed the logistics of purchasing supplies and paying the survey crew. The first group of commissioners met on October 17, 1732. It wasn’t long before they disagreed. They disagreed about the location of the center of the circle around New Castle. They disagreed about whether King Charles II’s charter for William Penn had intended a circle with a twelve-mile radius or a twelve-mile circumference (the latter would mean more land for Pennsylvania). The arguments ended in a stalemate. (A court later ruled that the twelve-mile reference was to the circle’s radius.)

Over time, new commissioners replaced old as vacancies due to illness, even death, required. In 1750, Benjamin Chew, a Philadelphia lawyer who was born in Maryland, was appointed secretary of the commission. He held the position for many years, and at times it sorely tried his patience. Survey crews crossing farmland often caused damage — enough so that in December 1760, the commissioners ordered the surveyors to obtain the consent of property owners before traipsing through orchards and gardens. Furthermore, they decreed, cutting down fruit trees to clear a vista, or line of view for the survey line, was not allowed without the landowner’s permission.

When commissioners attended boundary-line meetings, the lords proprietors paid for their travel, lodging, and meals. As men of high standing in their communities — landowners, clergymen, provincial officials, lawyers, and a professor — the commissioners stayed at inns and ate meals that met their standard of living. Expense accounts for the 1760 survey included such items as candles, Madeira wine, a teakettle, tea, chocolate, sugar, a Cheshire cheese, and rum. At times, one or more commissioners who had surveying experience actually worked as part of the survey crew and supervised portions of the line, such as setting boundary stone markers. But most often they met with the crew at inns for progress updates. Since the boundary commissioners served for a specified length of time, their commissions had to be periodically “enlarged,” meaning renewed. The commissioners did receive payment for their services.

In April 1751, colonial surveyors began running a line from Fenwick Island, on the Atlantic coast, straight west across the Delaware peninsula to Chesapeake Bay. They marked the start of the line, near the shoreline, with a crown stone made of local rock. The crown stone was carved with the Calvert coat of arms facing south and the Penn coat of arms facing north. The survey crew placed additional crown stones at five-mile intervals for the next twenty miles and wooden posts at every mile in between. (Within ten years, the first crown stone was found overturned, lying on the ground. Maryland Commissioner J. Beale Bordley reported a rumor that vandals digging for pirate loot were responsible.)

By May, the crew was mired in mud deep within the Pocomoke Swamp. (Pocomoke is an Algonquian word that means “black water.”) The crew waded around cypress knees and pushed aside clingy tangles of aquatic plants. They warded off snakes and snapping turtles, scratched itchy insect bites, and pulled off sucking leeches. The closest dry ground where they could pitch their tents was a two-mile hike away. Fed up, the disgruntled men went on strike. In a journal entry for May 8, 1751, John Emory and Thomas Jones, the surveyors and bosses, wrote, “This morning our Workmen combined together to Exhort higher Wages from us and . . . [would not] work longer with us unless we would enlarge their wages.” Threats to the strike leaders and discussion with the rest of the men resulted in all returning to work with no pay raise. The men continued under grueling conditions working “till late at night often to the mid-thigh in water.” In fact, water so inundated the exact spot where the twenty-five-mile marker was to be placed the crew couldn’t set the sixth (and last) crown stone. Instead they marked the line’s halfway point — dubbing it the Middle Point — with another crown stone. Despite nasty conditions, the crew completed the job, marking a straight line across the peninsula, a distance of almost seventy miles. But that only provided the peninsula’s southern boundary line between Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Between 1760 and 1763, another team of surveyors attempted several times to run the peninsula’s eighty-mile-long eastern boundary line, referred to as the Tangent Line. By the terms of the Chancery Suit, the Tangent Line was to extend northward from the Middle Point until it reached a point tangent to, or touching, the circle drawn around New Castle. If the line had run straight north along the meridian, it would have been much easier. Instead, to reach the tangent point from the Middle Point, the Tangent Line had to run at an angle of 3 degrees 32 minutes 5 seconds northwest from the Middle Point. That made the survey a lot harder — maybe even impossible. Imagine trying to draw a straight line from your home to the doorway of one specific building located eighty miles away with no reference points in between to guide your direction. That’s a bit what running the Tangent Line was like.

The surveyors’ northwestward trek from the Middle Point was fine for the first few miles. By June 16, 1762, conditions must have deteriorated, since Pennsylvania surveyor John Lukens wrote to Pennsylvania commissioner Richard Peters to inform him that he was aware of errors between his attempt at running the Tangent Line and earlier attempts. Frustrated, Lukens ended his letter, “I pray to be released from Trying to Do what I now Conceive to be Impossible, Viz. Run a Straight Line of ye Lenth of 80 miles.” His crew struggled on. At the end of August, Lukens informed Peters that navigating uneven, swampy areas near the Choptank River had greatly delayed his crew and caused them to have to make “three different offsets of the line.” (Under the instruction of the boundary commission, Lukens and his crew were to stop if they found the Tangent Line off course by more than ten feet for every five miles.) Optimistically, Lukens concluded the note with his hope that his crew would finish the Tangent Line within ten days to two weeks.

Unfortunately, by the time they reached the area where they expected to find the tangent point (the spot where the Tangent Line touched the circle drawn around New Castle), the line was too far east. The surveyors made yet another attempt during the summer of 1763. That line ended up 346½ feet too far west. The surveyors’ attempts had failed. Boundary bickering continued. And everyone wondered if the trouble would ever end.