WITH CHRISTMAS and the 1765 New Year’s festivities over, and the survey not scheduled to resume until spring, Mason and Dixon had plenty of time to relax at the Harlan home — to snooze, maybe ride the three miles to Joel Baily’s house and head across the road with him to Martin’s Tavern for a mug of ale. But Charles Mason was a man of action. Soon, colonial America and the promise of adventure beckoned. Mason heeded the call.

Despite the passage of a year, the Conestoga murders still weighed heavily on Charles Mason’s mind. And Lancaster, where the tragedy had occurred, was less than thirty-five miles away. Mason felt compelled to visit the site: “What brought me here was my curiosity to see the place where was perpetrated last Winter the Horrid and inhuman murder of 26 Indians, men, Women and Children, leaving none alive to tell.” (Mason was misinformed about the number of deaths.) The townspeople’s lack of action that day disturbed him: “Strange it was that the Town though as large as most Market Towns in England, never offered to oppose them [the Paxton Boys], though it’s more than probable they on request might have been assisted by a Company of his Majesties Troops who were then in the Town . . . no honor to them!” What Mason did, felt, and thought while visiting the town is a mystery. His journal is silent about that.

On his way back to Harlan’s house, Mason detoured through Pechway (today Pequea), near the east bank of the Susquehanna River. There he crossed paths with Samuel Smith, who in 1736 had been the sheriff of Lancaster County. As new acquaintances do, they chatted and shared news. Mason told Smith about surveying the boundary line. And Smith regaled Mason with the hair-raising story of Thomas Cresap. Mason heard how “one Mr. Crisep defended his house as being in Maryland, with 14 men, which [Sheriff Smith] surrounded with about 55.” Smith told Mason how Cresap and his friends “would not surrender (but kept firing out) till the House was set on fire, and one man in the House lost his life coming out.” After conversing with Smith, Mason realized how important it was that the boundary line be firmly established.

In mid-February, his desire to see more of America unquenched, Mason put on his wig, pulled on his hat, and set off for New York City. His journey barely started before trouble nearly finished it.

After spending the night at the home of Moses and Sarah McClean, Mason prepared to cross the Delaware River. Choosing a place where the river was about a quarter of a mile wide, Mason reined his horse down the riverbank and onto the ice. Partway across, a loud crack beneath the horse’s hooves froze Mason’s blood harder than the ice. Horse and rider plunged into the cold water. Watching his horse flounder, Mason feared the worst. Fortunately, the horse regained its footing and, without serious harm, the two safely reached shore.

After leaving New York, Mason rode south through New Jersey, where trouble found him yet again:

Met some boys just come out of a Quaker meeting House as if the Devil had been with them. I could by no means get my Horse by them. I gave the Horse a light blow on the Head with my whip which brought him to the ground as if shot dead. I over his Head, my hat one-way wig another and whip another, fine sport for the boys. However I got up as did my Horse after some time and I led him by the Meeting House, (the Friends pouring out) very serene, as if all had been well.

The next day, with wounded pride and a sore hip, Mason remained in bed. Two days later, he again crossed the Delaware River — this time by boat — and joined Dixon in lodgings a few miles from Mr. Bryan’s field and the Post Marked West. There the two men prepared a precise plan for running the Western Line.

One star, Delta Ursae Minoris, had steered the course for the Tangent Line. Mason now chose five key stars as the guides for the West Line. They are commonly known as Vega, Deneb, Sadr, Delta Cygni, and Capella. These stars are found in the constellations Lyra, Cygnus, and Auriga. Using this many stars would firmly anchor the team to the West Line’s latitude, which gradually curves around the earth.

WHILE MASON AND DIXON were in America, they had front-row seats for observing some of the earliest dissatisfactions that would slowly push thirteen American colonies on the road to rebellion. In taverns, at inns, and at the Harlans’ house, the surveyors certainly would have heard discussions about stamps. In every newspaper, they would have read articles about the Stamp Act. On June 20, 1765, the Pennsylvania Gazette carried word from Annapolis that “the Stamp Act is to take Place in America, on All Saints Day, the First of November next.” Ministers preached against the new law from their pulpits. And on November first, that day on “which the fatal and never-to-be-forgotten Stamp-Act” was intended to take effect, the bells in many colonial American towns tolled long and solemnly. Crowds demonstrated in the streets. Outraged merchants fussed and fumed.

What was the fuss over stamps?

First of all, they were not postage stamps. The act levied a tax on all American colonists for every piece of printed paper they used: newspapers, printed pamphlets, legal documents, land deeds, licenses, even playing cards. The paper used for these materials had to come directly from England, and a revenue stamp would be impressed into each sheet of paper. The amount of the tax — the cost of the stamp — varied according to the intended use of the paper and ranged from two pence up to six pounds. Parchment for a university degree cost two pounds; papers for court documents could cost from three pence to six pounds. The money collected would help pay the costs of stationing British troops along the boundary of the Appalachian Mountains, the border of Indian Territory. With the Stamp Act, Parliament reasoned, colonists would be paying, at least partially, for their own protection and defense.

The British government levied a tax on American colonists each time they used a piece of printed paper. A stamp, like the one shown here, noting the amount of money due, was impressed into the paper.

In response to the act’s passage, colonists held a Stamp Act Congress in New York City in October 1765. Twenty-seven delegates from nine colonies — Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and South Carolina — attended. The colonists objected to the new tax on important grounds: because none of the American colonies were able to choose members of Parliament to represent them, the British government had no right to levy taxes on them. In other words, they were being subjected to “taxation without representation.” The Stamp Act Congress declared that after January 1, 1766, Americans would resolve “not to buy any goods, wares, or merchandizes, of any person or persons whatsoever, that shall be shipped from Great-Brittain . . . unless the Stamp Act shall be repealed.” Further, the congress observed that British trade would suffer if American merchants refused to import goods from England.

Angry colonists protested the Stamp Act in various ways, including creating this parody of the official stamp.

The widespread protests of colonial people and the resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress gained the support of several members of Parliament. On February 21, 1766, Parliament soundly voted to repeal the Stamp Act, and the king gave his approval on March 18, 1766. Colonial activists had succeeded in their quest to repeal the Stamp Act. Mason and Dixon were thus on hand to observe the planting of one of the important seeds that grew into the American Revolution. “No Taxation Without Representation” became one of the battle cries when, in 1776, colonial Americans created new political boundaries by declaring themselves a country separate from England.

Beginning the West Line was as trouble-plagued as Mason’s winter break had been. Driving rains completely shut down operations on departure day, March 19. Gamely, the surveyors had managed to set one marker a half mile from the starting point. After that, dripping wet and muddy from head to toe, they called it a day.

The next day, weather hit them with two punches: plummeting temperatures and steady snow. When it stopped, two feet ten inches of snow blanketed the ground. Deep drifts barricaded the wagons. Five days passed before Jonathan Cope and William Darby, two of the crew’s most experienced chain carriers, dared travel the road from their homes in the Three Lower Counties to the Brandywine. All the team could do was wait. Mason and Dixon wanted to reach the bank of the Susquehanna River before mid-May. They hoped the weather delays wouldn’t completely derail their schedule.

The westward trek finally began on April 5. While hints of spring touched the air, enough chill remained to make cheeks and fingers tingle. Patches of melting snow slickened the ground and slowed wagon wheels. Eight days later — twelve miles and nine chains from the Post Marked West — tent keeper Alexander McClean, Moses’s nineteen-year-old brother (at least five McClean brothers worked on the West Line), helped set up tents in the line’s first camp. The tents’ linen fibers were spun in such a way that if a tent got wet, the fibers slightly untwisted and swelled, closing up the tiny openings between individual strands and making the tent more watertight. Some other tents used by the team may have been lined with wool. Like linen fibers, wool fibers expand when wet. In damp spring weather, the expanded wool would have reduced the amount of cold air that seeped through the tent walls. The surveyors did not describe the shape of the tents used by the crew, but it is reasonable to suppose the men had wedge-shaped or A-shaped tents similar to those used by the military. These tents, measuring six feet by six feet by six feet, weighed from fifteen to twenty pounds and provided sleeping quarters and shelter for up to six men. As the bosses, Mason and Dixon may have used a larger wedge tent or a small marquee tent, which would have weighed two, or even three, times as much. All the tents were supported by at least two upright wooden tentpoles, as well as a long ridgepole. These long, heavy poles were awkward to transport and unwieldy to handle during setup.

While Alexander McClean hammered tent pegs, full-time cooks Leven Hickman and Charles Platt unpacked kettles and knives, lit a fire, and prepared supper. Mason and Dixon discussed the past week’s work with John Harlan, who had joined the crew as an instrument bearer, and asked Cope and Darby to return to Mr. Bryan’s field in the morning to get the zenith sector. Optimistically, on April 30, the surveyors sent express messages to the commissioners saying they would reach the Susquehanna River in twelve days. The pressure was on.

Everyone settled in to camp, knowing the surveyors’ eyes would be glued to the skies for the next two weeks to confirm their course. Because the earth’s surface curves, Mason could plot the true course for a distance of only ten to eleven miles. So every time the crew had traveled about that distance, Mason spent time stargazing. After he confirmed that they were still properly on the latitude of the West Line (39°43′18.2″ N) — or making corrections if they weren’t — Dixon could resume chaining the next day confident that he was on course.

On May 11, at 26 miles 3 chains 93 links, the survey crew reached the east bank of the mighty Susquehanna River and made camp, exactly on schedule. At night, Mason stargazed. In the daytime, Dixon measured the width of the Susquehanna with the Hadley’s quadrant.

On May 25, as evening approached, Mason was hard at work across the river from camp. As he shifted his gaze from the task at hand, he noticed massive dark clouds on the horizon. Thunder grumbled low, and lightning flashed. Nerves on edge, Mason hurried to a boat:

[As] I was returning from the other Side of the River, and at the distance of about 1.5 Mile the Lightning fell in perpendicular streaks, (about a foot in breadth to appearance) from the cloud to the ground. This was the first Lightning I ever saw in streaks continued without the least break through the whole, all the way from the Cloud to the Horizon.

Even though the fierce spectacle awed him, as soon as his boat touched shore, he hustled away from the water and safely out of the lightning’s path.

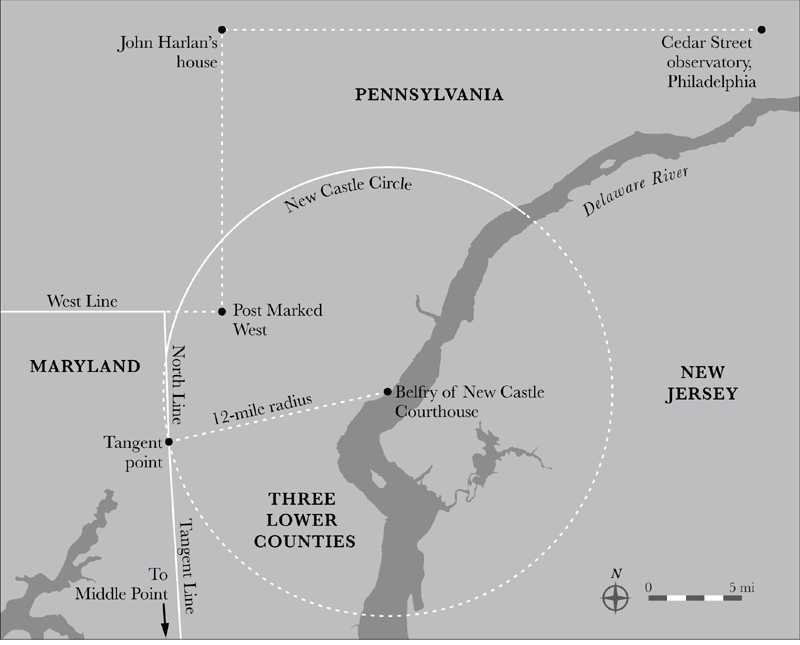

Having completed the survey as far as the Susquehanna River, the entire crew trudged back east, toward the Post Marked West, double-checking the accuracy of the set mileposts along the way, and then headed south. By June 1, they reached the tangent point, where they surveyed a short line called the North Line. This line, 5 miles 1 chain and 50 links long, extended north along the meridian from the tangent point to the point where it intersected the West Line in a meadow owned by Captain John Singleton. Surveying the North Line completed the eastern boundary, where Maryland, Pennsylvania, and the Lower Counties (Delaware) come together. Mason and Dixon marked the spot with a post that had a W carved on its west side and an N on its north side.

When combined, the Tangent Line and the North Line completed the eastern boundary between the land owned by the Calverts and that owned by the Penns. The solid white lines are boundary lines.

Pleased with the crew’s results, the commissioners decided it was time to set some of the permanent boundary stones, which had been shipped from England. Among the seven stones placed were one at the tangent point and one at the intersection of the North and West Lines. Afterward, the commissioners again sent the surveyors west to continue the line “in the same manner [from] the River Susquehanna . . . as far as the country is inhabited.” The farther west the survey crew traveled, the more rugged the countryside became. In some places, trees grew so closely together that a person with outstretched arms couldn’t walk without bumping against a tree trunk. The crew chopped down trees to clear Dixon’s vista and pressed steadily on.

No matter how carefully Moses McClean managed the crew and livestock, occasional problems cropped up. During a weeklong stop in mid-July, two horses wandered off. As he had five years earlier, McClean paid an express rider ten shillings to ride to Philadelphia and place an ad for the missing horses in the newspaper.

While McClean dealt with missing horses, the surveyors watched the five key stars and discovered that the line had drifted too far south by 56 feet (85 links). They corrected their position and continued westward. As the dog days of summer passed from July into August, sweat dripped from the axmen’s faces. At noon on August 8, a little over seventy-one miles from the Post Marked West, the laboring crew finally received some respite from the heat — though unfortunately, it was in the form of a fierce thunderstorm. Hail pelted the tents and shredded leaves from trees. Amazed by the size of the hailstones, Mason grabbed a large one and measured it before it melted. It was “one inch and six tenths in Length, one inch two tenths in breadth and half an inch thick.”

Meanwhile, back in England, the Penns and Lord Baltimore grew impatient, despite news from Maryland’s governor Sharpe that the whole line would not likely be finished in 1765. They read copies of the minutes of the Boundary Commission meetings, so they knew that progress had been made. Even so, the survey seemed to be taking a long time. The proprietors hoped the commission wouldn’t have to be extended for yet another year. Each day added, every delay reported, only increased the proprietors’ frustration over the mounting costs of an already expensive undertaking. But, as Governor Sharpe explained in a letter dated July 10, 1765, “the Taking [of] frequent Observations with their Sector is exceeding tedious & retards them sometimes for near three Weeks together I do not expect they will this Summer extend the Line by many Miles.” The commissioners wished the survey would end as much as the proprietors did. Traveling back and forth to boundary-line meetings was arduous and disruptive. There was, however, no way to hurry the stars.

Surveying the West Line was not all about computations. The commissioners had also encouraged Mason and Dixon to engage the colonists along the way. The commissioners had done so, realizing that keeping people informed was a good way to allay fears and anger about property issues. Phinehas Davidson, who lived near milepost 86, would have chatted with the surveyors, since their line might easily cross his property. He must have told them he was a pretty good cook, as Moses McClean later hired him. By the end of August 1765, the crew included more than forty men, many of whom worked as axmen. One of them was Phinehas Harlan, John and Sarah’s twenty-four-year-old son. Working for Mason and Dixon was a good way for him to save some money for his future — his sweetheart, Elizabeth, whom he hoped someday to marry, was waiting for him back at home.

A local resident visited the surveyors’ camp near milepost 95 on Sunday, September 22. Since it was the crew’s day off, the surveyors accepted his offer to go spelunking. Dixon, whose father operated a coal mine, was very familiar with large holes in the ground. But this cave, the resident assured him, was quite different. Dixon and Mason saddled up for the six-mile journey.

Carrying lanterns, the men ducked as they entered the cool, damp cave. After passing through the arched mouth, they straightened. “Immediately there opens a room,” Mason wrote, “45 yards in length, 40 in breadth and 7 or 8 in height. (Not one pillar to support nature’s arch).” The dim light of their flickering lanterns revealed formations that astonished them: it was like being inside a cathedral. “On the sidewalls are drawn by the Pencil of Time, with the tears of the Rocks: The imitation of Organ, Pillar, Columns and Monuments of a Temple.” Indeed, their guide told them that during the winter, local residents attended church services inside the cave. Profoundly moved, Mason described the hushed atmosphere of the large chamber as “Striking its Visitants with a strong and melancholy reflection: That such is the abodes of the Dead: Thy inevitable doom, O stranger; Soon to be numbered as one of them.” Further exploration of the cave brought them to “a fine river of water” and “other rooms, but not so large as the first.”

The black rectangle inset includes the area that surrounds mileposts 105–115 of the West Line.

Dixon’s map shows the crew crossed rivers, creeks, and mountains along this stretch of the West Line.

The next Sunday, Mason and Dixon forded the Potomac River and crossed into Virginia, where they saw a log fort — a reminder of the ever-present troubles in the wilderness — and a tavern. As was fairly common at the time, Mason and Dixon were known for enjoying wine, ale, and other alcoholic beverages. Their expense reports included receipts for wineglasses and liquor. What’s more, frontier taverns — busy places visited by both local residents and travelers — were the best places to go to catch up on news of all sorts.

By the end of the first week of October, at milepost 117, near North Mountain, they’d reached the end of the survey for that season. They remained camped there for three weeks, stargazing and confirming the accuracy of the West Line. With an ax, Dixon chopped a mark in a tree whose position had been precisely noted with relation to the positions of several stars at a certain time. The next season, Mason planned to recheck the line’s accuracy using the positions of those stars and the marked tree.

Having been instructed that the West Line should not cross the meandering Potomac River, the surveyors asked local resident Captain Evan Shelby to hike with them to the top of North Mountain and point out the river’s path. After showing them how the river looped about two miles south of the line, Shelby pointed out Allegheny Mountain, which the surveyors judged “by its appearance to be about 50 miles (in) distance in the direction of our Line.” The view from the summit of North Mountain was the surveyors’ last westward view of the season.

The next day, with winter on the horizon, Mason and Dixon packed the instruments and “left them (not in the least damaged to our knowledge) at Captain Shelby’s.” The crew began its return to the Susquehanna River, checking their offsets along the way. On November 8, at the settlement of Peach Bottom Ferry, Mason and Dixon discharged all hands and left for the town of York, where they met with the boundary-line commissioners for nearly a week. Did the commissioners celebrate on November 15, the second anniversary of the surveyors’ arrival in America? Or did they fill the surveyors’ ears with the proprietors’ complaints about time and money? The commissioners definitely piled on further instructions: proceed at once to the Middle Point, at the southern end of the Tangent Line, and supervise the setting of fifty boundary stones.

In early December, Mason and Dixon arrived at the home of John Twiford, on the Nanticoke River. They had come to know Twiford well when they’d surveyed the Tangent Line. They waited nearly two weeks at his house before a barge delivered twenty boundary stone markers to Twiford’s wharf. Another barge delivered an additional thirty stones on the bank of the Choptank River, midway along the Tangent Line. Wagons carried the stones and men hired by Reverend John Ewing, one of the Pennsylvania commissioners, along the Tangent Line as the men dug holes and set the stones. On January 1, 1766, with all fifty stones set, Mason and Dixon released the crew for the cold season and settled down for the winter with the Harlans at Brandywine Creek. With much work still to be done, the lords proprietors had no choice but to extend the boundary commission another year to December 31, 1766. Surely that would be enough time.

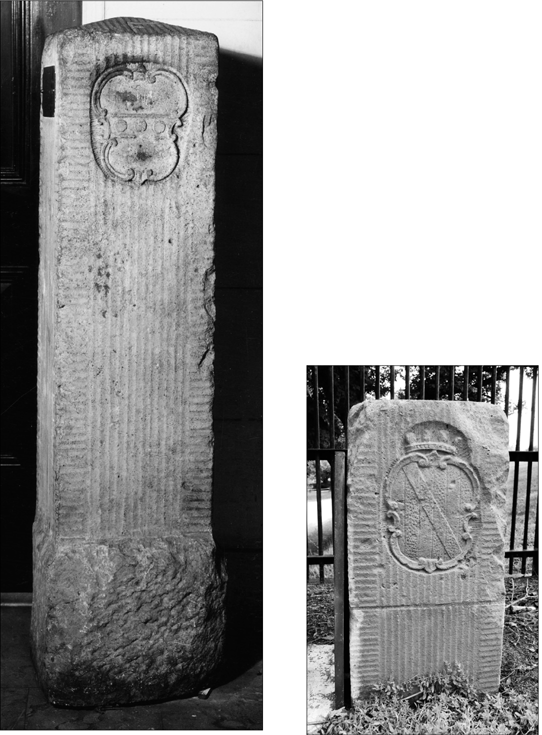

CREATING a permanently marked boundary line was critical. Mason and Dixon used boundary stones similar to those used by the crew that had surveyed the Transpeninsular Line several years earlier. The boundary stones were taken from limestone quarries on the Isle of Portland, in the English Channel along southwestern England. The stones are rectangular pillars, with each stone twelve inches across and the top tapering to a shallow pyramid. They were 3½ to 4½ feet tall and weighed 300 to 600 pounds. Some of the stones, called crown stones, had the Calvert and Penn families’ coats of arms carved on opposite sides; these were placed at five-mile intervals. Others were simply inscribed with a capital M on the side that faced Maryland and a P on the side facing Pennsylvania; these marked each mile between the crown stones. In a letter to Cecilius Calvert, Governor Sharpe estimated that the team would need between fifty and sixty crown stones and about two hundred regular mile markers. The stones, shipped from England as ship ballast, were unloaded onto wharves in Maryland, where they were shipped inland by barge and/or wagon.

The crown stone on the left, seen full-length, shows the Penn family coat of arms, which would have faced Pennsylvania. The crown stone on the right shows the Calvert coat of arms, facing Maryland.