INSTEAD OF OFFERING Mason and Dixon tickets back to England, the commissioners had new instructions for more work. The first job was surveying an eleven-mile line from the Post Marked West east to the Delaware River. Although this line wasn’t part of the boundary line, knowing its length would allow the commissioners to calculate exactly how far west Pennsylvania extended. The king’s charter to William Penn defined the westernmost limit of the province as five degrees of longitude west of the Delaware River. This job took Mason and Dixon slightly less than a week.

The second job, however, was huge: return to the westernmost end of the West Line and continue the line until it reached the spot exactly five degrees longitude west of the Delaware River, as had been established in the charter. Accomplishing this job meant crossing the boundary into land under the jurisdiction of the Six Nations. Under the king’s 1763 proclamation, English colonists were not supposed to settle there, and traveling through this territory without the confederacy’s consent could cause misunderstandings that might have violent consequences. So Governors John Penn and Horatio Sharpe wrote letters to Indian agent William Johnson, who agreed to ask the Six Nations’ leaders for their consent, which the governors hoped would arrive by March or early April 1767. Mason and Dixon realized that this meant more work, more delays, and more time in America as they awaited news from Johnson at the Harlans’ house. Meanwhile, anticipating the Indians’ consent, the lords proprietors had extended the boundary-line commission for yet another year, through December 31, 1767.

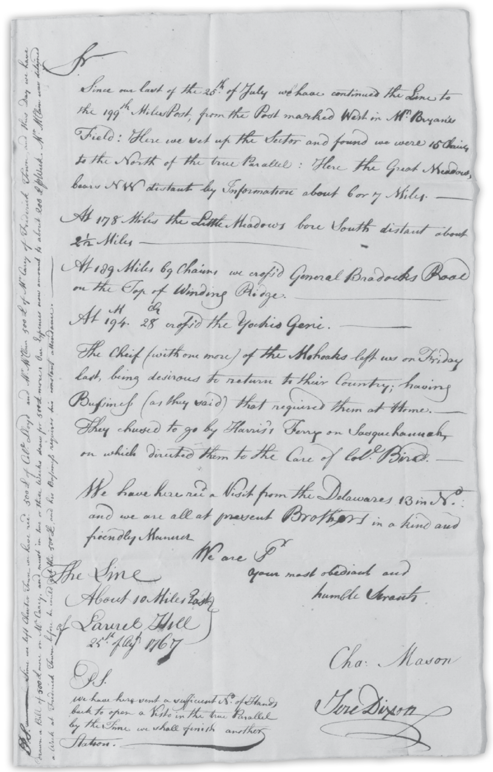

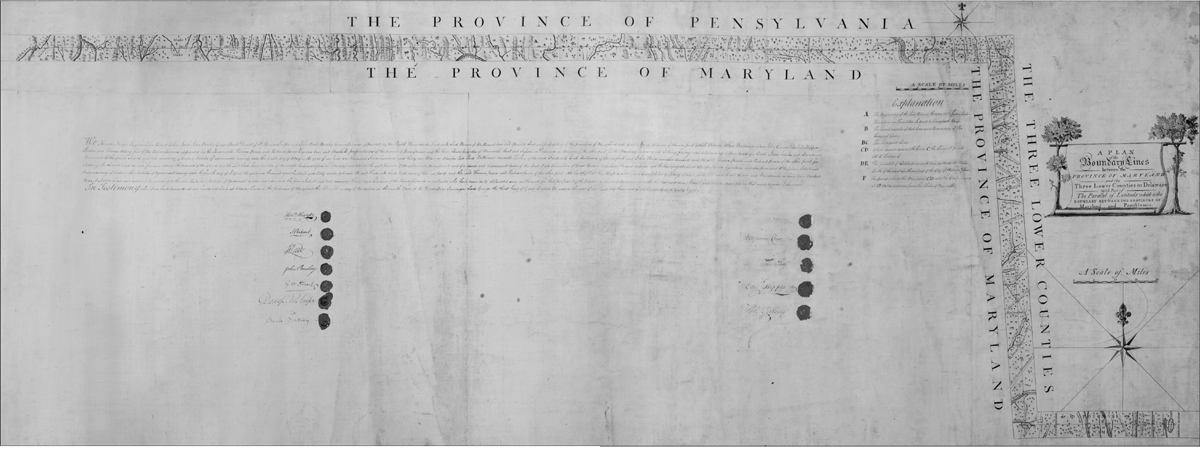

Within days of their arrival at the Harlans’ house, the surveyors used the zenith sector to observe the same stars they’d recently observed at the Middle Point, collecting more of the star-related data they would need to compute the length of a degree of latitude. But in January 1767, Mason and Dixon also began gathering information of a different sort. Their new observations, made at the request of the Royal Society, would help scientists understand how — or if — gravity was affected by latitude. They used two pendulum clocks. One belonged to the proprietors and had already been used many times during the survey. The other clock had been made by John Shelton, a famous English clockmaker, and was shipped to them by Nevil Maskelyne of the Royal Society, who had used it to time the transit of Venus on Saint Helena Island. Mason and Dixon recorded the time shown on both clocks at least twice daily, noting any differences. Maskelyne also sent two thermometers made by John Bird, the man who had made the zenith sector. Twice daily, Dixon and Mason used these to record the temperature of the air inside and outside the observatory tent. All this data would help support or refute a scientific hypothesis.

Scientists of the day hypothesized that Earth’s gravitational force varied with latitude — so that, for example, the gravitational force along Pennsylvania’s latitude was different from that along Saint Helena’s latitude. They hoped the Shelton clock would help prove it. Each swing of the clock’s pendulum advanced a set of gears that in turn moved the clock’s hands. Earth’s gravity pulled on the swinging pendulum. If gravity’s force was stronger in the clock’s current location than it had been in its previous location, the pendulum’s movement would be slightly slower and the clock would lose time. If gravity’s force was lower, the pendulum would swing more freely and the clock would gain time.

The Shelton clock’s pendulum was made of brass; the proprietors’ clock had a walnut pendulum. The brass pendulum would shrink or expand minutely in response to cold or heat, which could affect the rate at which it swung.

The Shelton pendulum clock used by Mason and Dixon in their observatory in Harlan’s garden. The base and pedestal were added later.

On New Year’s Day, the outside temperature plummeted to 22° below zero Fahrenheit. Conditions inside the tent, at 9° below zero Fahrenheit, weren’t much better. The metal transit and equal altitude instrument was so cold that “the immediate touch of the Brass was like patting one’s Fingers against the points of Pins and Needles.” On January 27, three days of freezing rain coated Mason and Dixon’s world with ice. Although sunlight sparkled magically on the ice, “the limbs of the Trees broke in a surprising manner, with the weight of clear Ice upon them.” Despite dangerous falling branches, the two men faithfully recorded times and temperatures. With observations completed at the end of February, Mason packed the Shelton clock and sent it, along with all their time and temperature records, to the Royal Society in England. There, scientists would compare the data with similar records kept by Maskelyne, using the same clock, on Saint Helena. Mason and Dixon’s observations did help prove the hypothesis. It was later confirmed that gravity had indeed affected the rate of the pendulum’s speed in Pennsylvania, causing a variation from the rates observed at Saint Helena.

Even as the Shelton clock stopped ticking, time marched forward. The commissioners, surveyors, and provincial proprietors all waited impatiently for word to arrive from William Johnson and the Indians.

William Johnson was a longtime resident of the province of New York. He lived on land near Mohawk territory, spoke Mohawk, and was in a common-law marriage with Molly Brant, a Mohawk woman. At Six Nations council meetings, he dressed in Mohawk clothing and participated in ceremonial dances. Johnson understood and respected cultural boundaries that most colonists did not.

Acquiring permission for Mason and Dixon to survey beyond the colonies’ borders would require patience and diplomacy. First, Johnson insisted that “all the Chief Sackems [sic] and principal Warriors of the Six Nations” be present at the council meeting during which he would request permission. He estimated that assembling the large group at a place conveniently located and supplying them with presents would cost about five hundred pounds in New York currency (equivalent to three hundred pounds in British currency), an expense the lords proprietors of the two provinces would have to bear. Additionally, plans being developed in London regarding a different boundary line between England’s colonies and Indian territory had become mired in governmental meetings. This proposed line was completely unrelated to the West Line, but Johnson had to allay the Indians’ suspicions that Mason and Dixon’s survey was connected with the stalled boundary line under discussion in London. Furthermore, he needed to schedule the council meeting before the Indians’ hunting season began.

Delayed by unusual spring flooding, the council meeting didn’t occur until May 8 to 11, 1767. As protocol required, Johnson began by presenting strings of wampum to the Indians. Wampum presented during a council meeting was not being used as money. Instead, it signaled that a matter of importance was being discussed and considered. The three strings Johnson offered signified the beginning of a time for discussion. Johnson told the people gathered at the meeting about the commissioners and about the surveyors from England. He said, “From their desire to make you all easy in your minds, they wou’d not go any further ’till they had obtained your voluntary Consent, and procured some of your People to be present, whom they wou’d pay for their attendance.” He further said that to show their earnest truth in the matter, the commissioners had asked Johnson to lay before them a belt of wampum, which he did. A belt of wampum had even greater significance than strings. Belts were reserved for very important matters, such as matters concerning land. Johnson assured the council participants that the line being surveyed — the West Line — would not affect even the smallest bit of Indian land. Its purpose was only to settle a boundary-line dispute between the governors of Pennsylvania and Maryland. He showed them Governor Penn’s letter. After further discussion, the council consented to the governors’ request. They would select and send a group that would act as escorts for Mason and Dixon’s crew.

On June 2, an express rider brought word of the Indians’ consent to the surveyors at the Harlan home at the Brandywine. At last, Mason and Dixon could begin preparations to go west. They settled accounts with John Harlan and paid Joel Baily for repairing some instruments. On June 12, Jonathan Cope and six more instrument bearers departed for Fort Cumberland with the zenith sector; another wagon loaded with instruments soon followed. Last but not least, Mason and Dixon rehired Moses McClean, who in turn rehired many of the old crew. The surveyors also hired two guides. Unlike previous seasons, in which the surveyors had traveled across settled lands, surveying the far western line required the aid of men familiar with the area. Unpredictable rivers, steep cliffs, and boggy ground were only some of the obstacles that posed serious threats to the crew. Proceeding without guides would have been foolhardy. With the logistics well in hand, Mason and Dixon saddled up, this time for a journey into territory that was, as yet, largely unexplored by Europeans.

When Mason and Dixon arrived at Fort Cumberland on July 7, it bustled with a level of activity it hadn’t seen in a while. There, the surveyors finally met Thomas Cresap. Knowing they would be living in tents for the next few months, they gladly accepted Cresap’s invitation to spend the night at his beautiful estate near the fork of the Potomac River.

Meanwhile, Moses McClean finished final preparations. For this journey, the crew would need to haul more supplies than they had previously, when they were able to purchase provisions along the way. Wagons creaked under the weight of 657 pounds of bacon and 644 pounds of flour. Four bushels of oats for the packhorses shared a wagon bed with candles, thread, and ink powder. McClean even bought cooking pots for the Six Nations Indian escorts who would join them shortly. He employed more crewmen. Phinehas Davidson, whom they’d met the previous year while surveying near his home at mile 86, was one of the five cooks McClean hired. Like many of the crew hired during that summer and autumn, Davidson remained with the survey and worked full-time through mid-November.

The survey crew was a sight to behold as it chopped, jingled, and rumbled westward. At this point, the crew numbered more than sixty-five men, with eight instrument bearers, three tent keepers, and thirty-seven axmen among them. Trailing at the end of the party, fifty-five sheep, driven by shepherd James Reid, trotted along the newly blazed trail.

On July 16, just past mile 169, escorts from the Six Nations — fourteen Mohawks and Onondagas — arrived in camp accompanied by Hugh Crawford, their interpreter. Two of them, Soceena and Hannah, were women, the only women ever mentioned as traveling with the survey party.

Unbeknownst to Mason and Dixon, the boundary commissioners had narrowly avoided chaos for the survey party. In mid-June, the Pennsylvania commissioners had received word that 100 to 130 members of the Six Nations had assembled and were preparing to join the surveyors. Frantic about the enormous cost a group that large would add to the survey’s already hefty budget (by December 1767, the survey’s cost for the year would reach 6,600 pounds, three times the cost of the 1765 season) the commissioners took immediate action. They sent an express rider to deliver a message to another Indian agent, instructing him “to make the [Indians] a small present of powder and ball, flour and other necessaries as a satisfaction for their trouble” in assembling, and “to use his utmost endeavours to persuade them to return home.” The commissioners stipulated that no more than one hundred pounds be used to purchase the presents.

Fully aware of frontier tensions, the commissioners cautioned Mason and Dixon:

As the public Peace and your own Security may greatly depend on the good Usage and kind Treatment of the Deputies [the Indian escorts], we commit them to your particular Care, and recommend it to you in the most earnest Manner not only to use them well yourselves but to be careful that they receive no Abuse or ill treatment from the Men you may employ in carrying on the said Work, and to do your utmost to protect them from, the Insults of all other persons whatsoever.

This admonishment was not only morally justified; it would also help keep the team safe.

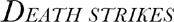

Mason and Dixon’s 1767 letter to commissioner Benjamin Chew reporting the visit from the Lenni-Lenape, whom they referred to as Delawares

For the next month, the crew and its Mohawk and Onandaga escorts pushed westward. Near the 189-mile mark, the group crossed General Braddock’s road at the place where it swung north toward the site of Fort Duquesne. Familiar with the road’s route, the crewmen knew they were approaching land traveled and used by members of the Lenni-Lenape and Shawnee tribes, traditional enemies of the Six Nations. At a snail’s pace, growing more nervous with each step, the crew edged onward.

On August 17, at 199 miles 63 chains 68 links, tent keepers James Reid and Alexander and James McClean pitched camp. Not long afterward, thirteen Lenni-Lenape strode into camp. One of them —“the tallest man I ever saw,” according to Mason — introduced himself as the nephew of a Lenni-Lenape named Captain Black-Jacobs. Hugh Crawford spoke with them and explained what the surveyors were doing. Mason did not mention how long the visitors stayed. But he and Dixon felt the visit went well, writing to commissioner Benjamin Chew, “We are all at present Brothers in a kind and friendly Manner.” The visitors left the camp without further incident. Even so, the crew’s unease grew. Perhaps the Mohawk and Onandaga escorts felt similarly, as on Friday, August 21, two of the Mohawks “left us . . . being desirous to return to their Country; having Business (as they said) that required them at Home.”

Turning to their work, the surveyors divided the crew into two groups, one to clear the vista eastward, back toward Savage Mountain, the other to continue west. The men heading west worried that decreasing the number of their group could increase the likelihood of an attack by the Lenni-Lenape or the Shawnees.

In their free moments, Mason and Dixon swapped stories with Hugh Crawford. For nearly three decades, first as a trader and later as an officer in the French and Indian War, Crawford had traveled extensively in the lands west of the colonies. He’d visited the Ohio Territory and floated down the Mississippi River. He told the surveyors of wide rivers deep enough to accommodate large ships and sloops. He told them of rich, fertile land. He told them about Illinois, about eight hundred miles from where they were sitting, “through which you may travel 100 miles, and not find one Hill.”

By September, the total number of the crew had swelled to more than 110. Even split into two groups, the traveling men, sheep, cows, horses, and the accompanying sounds of axes chopping wood created a noisy presence in the wilderness. The uneven, rough ground forced Moses McClean to replace wagons with packhorses. Thirty-two packhorse drivers tended as many as four or five horses each. Drivers William Baker and John Carpenter signed on at the end of August and quickly adjusted to the daily routine. When it was time to move camp, they roped food, barrels, kettles, and other supplies securely onto the horses’ backs. At other times, Baker and Carpenter harnessed the horses and hauled felled trees and brush from the vista. Like all crewmen, they kept one ear cocked for warning shouts about falling trees so they could pull their horses out of harm’s way.

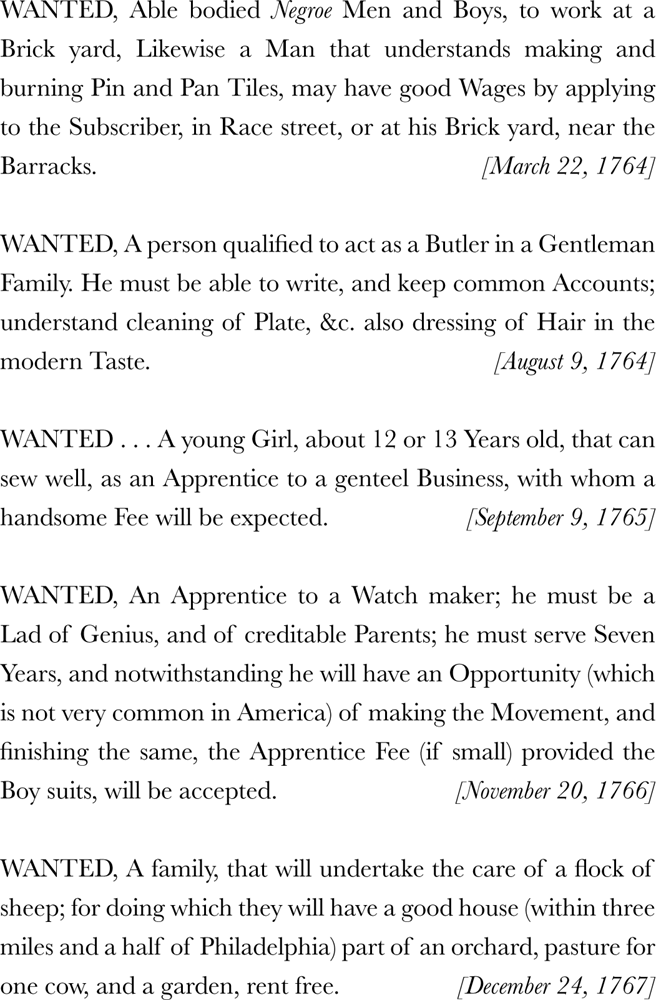

MASON AND DIXON hired many men while they were in America. But they weren’t the only employers looking for help. In colonial times, prospective employers placed want ads in the newspaper, just as they do today. Had you been looking for a job while the surveyors were hiring, here are some of the positions you would have seen advertised in the widely circulated Pennsylvania Gazette:

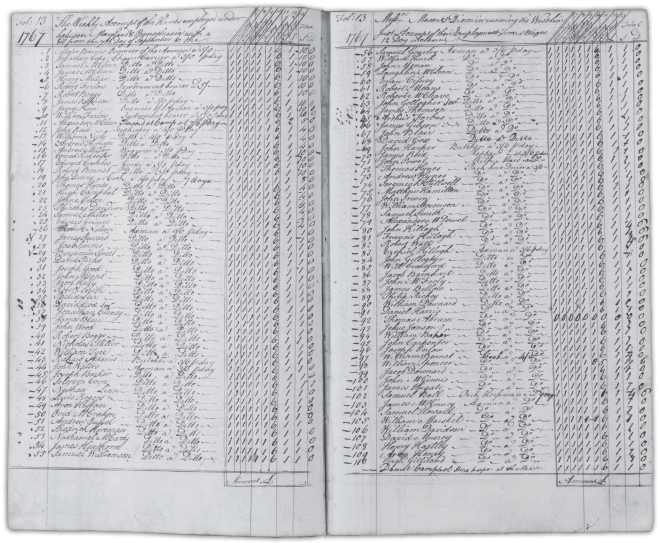

By September 7, 1767, Moses McClean needed two pages in his account book just to list the crew. Monies received were recorded on a separate, much shorter, page.

John Powel was in charge of different animals — cows! He is alternately listed in McClean’s account ledger first as “Cow Milker” and thereafter as “Milk Maid.” Due to lack of refrigeration, milk spoiled quickly. The only way the cooks could get fresh milk for cooking was by bringing cows with them. The herd eventually grew to ten.

When the crew paused along the banks of the Cheat River, Mason spent some time fishing. He was delighted when he “found plenty of fish of various sorts, and very large, particularly cat fish.” Mason also caught a lizard nearly a foot long but made no mention of what he did with it. Dixon looked at the rocks in the area, easily identifying coal, which reminded him of his experiences in the coal mine his father operated.

While Mason and Dixon noticed fish and rocks, their Indian escorts wondered just how far west the surveyors planned to go. Mistrust of the crew’s motives, as well as apprehension about encounters with enemy warriors, led to growing discontent. When two of the Mohawks heard that the surveyors intended to cross the Cheat River, they requested a meeting. Hugh Crawford and Mason and Dixon must have presented a convincing argument, because the escorts allowed the surveyors to cross the river and continue west.

Dr. Vause’s medicines were useful for treatment of common ailments, but they were of no help on September 17. At 221 miles from the Post Marked West, Mason and Dixon sent instrument bearers to fetch the zenith sector from their previous camp. Camp setup was well under way. Packhorse drivers William Baker and John Carpenter were busy tending to their horses. And then an axman’s blade bit into a tree trunk for one final blow. The tall tree leaned, slowly at first, and then faster as it toppled toward the ground. Unknowingly, Baker and Carpenter stood directly in its path. Before they could move, the heavy trunk crashed down. Both men died at once. News of the tragedy quickly spread through camp. That night, the deaths of William and John reminded everyone how dangerous their work was. Many of the men grumbled about their safety.

On September 29, at the east bank of the Monongahela River, 222 miles from the Post Marked West, a group of twenty-six crewmen confronted Mason and Dixon. The visiting Lenni-Lenape had worried them, yet they had willingly stayed with the survey. However, crossing the Monongahela River meant that they were passing into Lenni-Lenape and Shawnee territory. Now they were afraid. And they could see that their Indian escorts were uneasy, too. The twenty-six men flatly refused to cross the river and announced that they were quitting. Nothing Mason or Dixon said changed their minds. The surveyors had no choice but to pay the men and release them. They did persuade the fifteen remaining axmen to stay and sent word to Forts Cumberland and Redstone for replacements for the twenty-six who’d quit, if they could be found. The remaining crew crossed the Monongahela, climbed its western bank, and walked deeper into Indian Territory.

Unbeknownst to Mason and Dixon, they were being watched. About two miles from the river, three Indians — two men and a woman — approached them. As the trio was dressed almost completely in European-style clothing, the surveyors had no idea to which tribe they might belong. But the Mohawks immediately recognized them as Lenni-Lenape. Stepping forward, the leader of the Mohawk escorts greeted the visitors. He learned that the older man was Catfish, a “Chief of the Delaware Nation.” Catfish’s wife and nephew accompanied him. As custom required, the men sat and held a council, during which the Mohawk leader presented Catfish with two strings of wampum. He then explained who Mason and Dixon were, what they were doing, and why members of the Six Nations were with them. Catfish accepted the wampum and promised to bring it to the people of his town and relay what he had been told. Though the meeting was cordial, even the Mohawks and Onondagas were disquieted after Catfish left.

New workers from Fort Cumberland arrived at the end of the first week in October. Almost on their heels, a party of eight Senecas arrived. The Indian escorts welcomed them gladly, since the Senecas were members of the Six Nations. The Seneca party, equipped “with Blankets and Kettles, Tomahawks Guns and Bows and Arrows,” was on its way south to fight the Cherokee. They decided to travel with the survey party for a time. During that time, all of the Indians and Hugh Crawford discussed news from distant council fires. The Lenni-Lenape and Shawnees weren’t the only angry Indian groups; the Six Nations peoples also felt a growing mistrust toward European colonists. After two days, the surveyors gave the Senecas some gunpowder and war paint, and the party resumed its journey south. Yet the Indian escorts who still remained with the survey continued discussing matters among themselves.

On October 9, 1767, at 231 miles 20 chains, the surveyors crossed a well-trodden Indian warpath. Within two miles, the chief of the Mohawks requested a meeting with Mason and Dixon. “This day the Chief of the Indians which joined us on the 16th of July informed us that the above mentioned War Path was the extent of his commission from the Chiefs of the Six Nations that he should go with us, with the Line; and that he would not proceed one step farther Westward.” For a day, Mason and Dixon pled their case to continue west: they had almost reached Pennsylvania’s western limit — five degrees of longitude from the Delaware River. But the escorts would not budge, and the surveyors had no choice but to accept their decision. William Johnson later informed Richard Peters that the Mohawk leader had “Suppressed part of what he might have informed you.” Suspicions of English deceit, grievances over broken promises, and rumors of Indian enslavement — circulated by French agitators — had pushed the Indians to a level of anger higher than Johnson had ever seen, short of war. Although it arrived after the fact, this information further validated Mason and Dixon’s acceptance of the escorts’ decision.

The black rectangle inset marks the end point of the West Line.

On his final map, Dixon even included the Indian War Path that Mason noted in his journal.

Near a ridge now called Browns Hill, Mason and Dixon established their westernmost camp and spent the week of October 11 observing the stars. While they were there, a large group of Lenni-Lenape, among them Prisqueetom, brother to the king of the Lenni-Lenape, visited the camp. Prisqueetom, who was eighty-six years old, told Mason that he and his brother “had a great mind to go and see the great King over the Water; and make a perpetual Peace with him; but was afraid he should not be sent back to his own Country.”

In this western camp, the surveyors monitored their five key stars — Vega, Deneb, Sadr, Delta Cygni, and Capella — for the last time. These stars, old friends by then, had guided them along the West Line for more than a year. And it was time for another marker:

On the top of a very lofty Ridge . . . at the distance of 233 miles 17 Chains 48 Links from the Post marked West in Mr. Bryan’s Field, we set up a Post marked W on the West Side and heaped around it Earth and Stone three yards and a half diameter at the Bottom, and five feet High.

With cutting-edge scientific instrumentation, meticulous observation, and a hardworking crew, Mason and Dixon had successfully broken the established boundaries of what a survey could accomplish. Even though the West Line ended short of Pennsylvania’s western limit, Mason and Dixon’s very, very long West Line still inscribed a parallel of latitude on Earth’s surface — the first of its kind anywhere.

Although the West Line survey was complete, a lot of work remained. As soon as the team erected the stone cairn, axmen began cutting the vista east to milepost 199, where it would connect with an already completed section of the vista. Tensions eased as the group returned to familiar territory.

Sadly, though, another death occurred. Jacob, one of the Indian escorts who had worked many years as a scout for the British, died of an unmentioned cause. The surveyors had a coffin made for him and purchased a black burial shroud. Jacob’s remains, along with “a silk handkerchief sent to his widow,” were carried to Philadelphia, where he was “decently buried.” Jacob’s pay of forty dollars, a higher amount than that paid to most of the other Indians, was sent to his widow.

On November 5, Hugh Crawford and the Indians departed. They were paid, in colonial currency, a total of 631 dollars (the equivalent of slightly more than 236 pounds) for their service. The Mohawk Leaders — Hendricks, Daniel, and Peter — received payment twice that of the other escorts. Three of the men also received a rifle in partial payment. Soceena and Hannah received payment equal to that of the lower-paid Indian men. Shortly after the Indians left, all but thirteen of the survey’s crewmen departed for their homes too.

Meanwhile, the final load of boundary stones lay waiting at the foot of Sideling Hill, at milepost 134. Earlier that season, Mason and Dixon had received an estimate for transporting them to the section of the line between mileposts 134 and 199. The exorbitant fee requested was twelve pounds — nearly equal to the weekly wages of a dozen crewmen! Astounded, Mason and Dixon refused, a decision later applauded by Pennsylvania commissioner Benjamin Chew, who complimented the surveyors, noting they had “acted very prudently in refusing to give the extravagant Price.” Mason sent a letter to Hugh Hamersley, Lord Baltimore’s agent, to report that they’d left seventy boundary stones at Fort Frederick. Ironically, considering the expense of cutting the stones and shipping them to America, Mason wrote, “In all the Mountains we have past over this year and almost at every Mile Post there is good stone if not superior to those sent from England.” In lieu of the heavy markers, Mason and Dixon followed the commissioners’ instructions and, without any further visits from the Lenni-Lenape, marked the line on the tops of the western ridges with cairns similar to the one on the westernmost ridge. The work satisfied them: “The Marks we have erected may be seen from Ridge to Ridge in most Places and it will take a great length of Time (if ever) to destroy them.”

The crew marched east in snowy weather that grew progressively worse. At Savage Mountain, they trudged through snow twelve to fourteen inches deep. On November 20, with hands so cold their fingers wouldn’t open and close, they sheltered in a Mr. Kellam’s house, where seven of the crewmen quit. Cold, tired, and forced to find new men to complete the work, Mason and Dixon splurged on a filling, hot meal. On November 28, after paying the crewmen, the surveyors sat down to a hearty dinner of venison, corn pudding, and turnips.

Later, when the surveyors reached the top of Town Hill, they received a pleasant surprise: Robert Farlow, a trusted instrument bearer who’d worked with them for three years, awaited them. In the beginning of October, Mason and Dixon had sent him east to set boundary stones on an eastern section of the line. When the surveyors arrived on Town Hill, Farlow and his men had just finished building the cairn there. Mason and Dixon were even more pleased when Farlow told them all the markers were in place from milepost 135 eastward to the Post marked West, except for those at miles 77 and 117, which they’d placed slightly off the line due to marshy ground and a gigantic boulder. As the size of the crew dwindled, Moses McClean began selling off unneeded equipment: blankets, kettles, two axes, a pair of hobbles, a saddle, a tent, and ten cows.

By December 12, a skeleton crew of fewer than ten men remained with Mason and Dixon, who dispatched an express message to the commissioners to expect their arrival in Philadelphia — mission accomplished — on the fifteenth of December.

The surveyors spent Christmas Day meeting with the commissioners, including Benjamin Chew, who was eager “to put an end to this tedious Business.” Mason and Dixon were relieved to hear the commission had “no further occasion for us to run any more Lines for the Honorable Proprietors.” Was their work for the Penns and Lord Baltimore finally done?

It seemed not, as almost in its next breath, the boundary commission issued two additional tasks. First, Dixon, a fine draftsman, was to draw a map of the line. Second, knowing that Mason and Dixon were computing the length of a degree of latitude for the Royal Society, the commissioners asked them to compute the length of a degree of longitude in the parallel of the West Line. The surveyors undertook both tasks at the Harlans’ house.

The second task took a week of mathematical computation. Using their many star observations and chain measurements, and supposing Earth was a perfect sphere, Mason and Dixon calculated the length of a degree of longitude along the West Line to be 53.5549 miles. However, in their note to Richard Peters, Mason wrote, “But the Earth is not known to be exactly a Spheroid, nor whether it is everywhere of equal Density. . . . We do not give in this as accurate.” One task was complete.

Dixon finished drawing the map at the end of January, and they delivered it to Mr. Peters for his approval on January 29. While in Philadelphia, they stopped at the State House and checked on the zenith sector and transit instruments, confirming that they were still safely stored. With the second task completed, they decided to finish computing a degree of latitude for the Royal Society.

On February 1, Mason and Dixon prepared to gather the rest of the information they needed to measure and compute a degree of latitude. Joined by their good friend Joel Baily and a few others, Mason and Dixon laboriously remeasured the distance from the Harlans’ garden all the way to the Middle Point. Even though they had already measured the distance in 1764 with a Gunter’s chain, the Royal Society wanted more precision. They wanted the distance measured with four brass-tipped wooden rods, each ten feet long, and a five-foot-long brass standard, all sent directly to Mason and Dixon for this purpose by Nevil Maskelyne. Maskelyne especially cautioned Mason and Dixon to “Keep the rods as dry as you can, for if any thing alters their length it is to be supposed to be changes of moisture and dryness. . . . Always take care to bring the ends of the rods to meet, without any shock, and don’t trust this to your Labourers.” Maskelyne didn’t trust anyone but Mason and Dixon. Every measurement was double-checked.

They recorded the temperature multiple times during the day. Their reason for doing so was that in addition to the wet and dry changes mentioned by Maskelyne, changes in temperature slightly altered the length of the wooden rods, the wood expanding in heat and shrinking in cold.

The trip to the Middle Point lasted from February 23 until June 4. Wading through swampy water became routine. Twice they crossed water that was four to five feet deep. Both times, Mason noted that it was others, not he, who went in that water.

At the Middle Point, they lodged for several days at Mr. Twiford’s house, one of Mason’s favorite places in America, before returning to the Harlans’ house, where Mason combined the earlier data collected at the Middle Point with the crew’s new measurements. He calculated that the length of a degree of latitude — the arc of the meridian from the Stargazer’s Stone to the Middle Point — at their location was equal to 68.81 miles — a 0.69-mile difference from the measurement of a degree of latitude in Europe. While the difference might seem small, it did help scientists prove that Earth was not perfectly spheroidal — an important confirmation. Mason submitted the results to the Royal Society, which received the information with great appreciation.

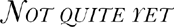

The Royal Society was delighted that Mason and Dixon had successfully measured a degree of latitude in North America. The vertical line at the center of the map is the degree that they measured.

It was nearly the end of June before the surveyors completed their measurements and calculations. As soon as they finished, they notified the boundary-line commissioners that they were ready to leave for England. Rather than agreeing, the commissioners instead informed the surveyors that they wanted Dixon’s map engraved and printed before the two men departed. One of the commissioners hired Mr. Dawkins, a local engraver, to do the work. Unfortunately, Dawkins quit midway through the job. Engraver James Smither completed the work, and the copper plate was delivered to Robert Kennedy’s printing office on Third Street in Philadelphia. Mason and Dixon stepped closer to their departure for home when they picked up two hundred copies of the boundary-line map on August 16. Mr. Smither presented his bill for engraving several days later. It was for twelve pounds — the exact amount Mason and Dixon had saved by not hauling boundary stones to the tops of the farthest western ridges.

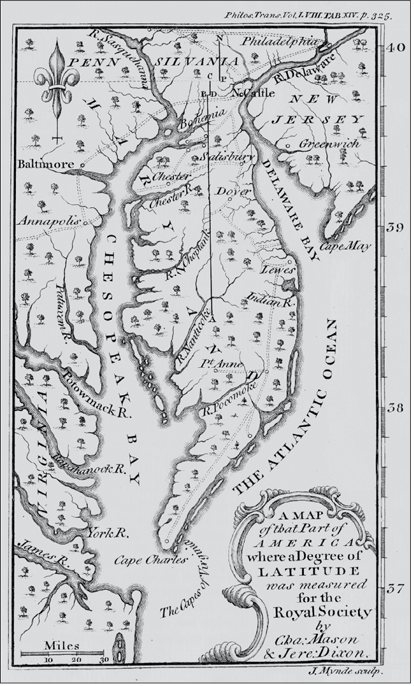

Copies of Jeremiah Dixon’s map were delivered to the boundary commissioners, who signed and stamped their acceptance of the map with wax seals. The column on the left contains the Maryland commissioners’ signatures; the column on the right has those of the commissioners from Pennsylvania.

Maryland commissioners: Horatio Sharpe, John Ridout, John Leeds, John Barclay, George Stewart, Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer, and John Beale Bordley. Pennsylvania commissioners: William Allen, Benjamin Chew, John Ewing, Edward Shippen Jr., and Thomas Willing.

Mason and Dixon spent the next three weeks settling their accounts, wrapping up loose ends, and attending one final meeting with the commissioners. On September 8, almost five years after they had arrived in America, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon said good-bye to Philadelphia and journeyed to New York. On September 11, 1768, at 11:30 in the morning, they boarded the Halifax Packet and set sail for Falmouth, England. The same day, Mason concluded his journal, writing, “Thus ends my restless progress in America.”

For most of the colonists, Mason and Dixon’s line resolved the territorial disputes that had pitted landowners against each other. But a few colonists, especially those whose lands straddled the line, battled on, filing land disputes that had to be decided in court. Sometimes the result was that a colonist from one province lost his property to a claimant from the other province. These out-of-luck colonists had no choice but to move.

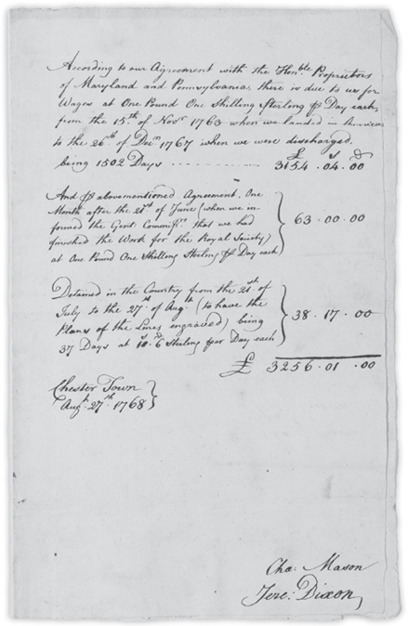

In August 1768, shortly before they left Pennsylvania, Mason and Dixon gave Benjamin Chew their invoice for 1,502 days’ worth of work. The total bill was for 3,256 pounds, one shilling.