MASON AND DIXON’S survey was done. Eight years later, the Declaration of Independence essentially made the Calvert and Penn boundary dispute moot. Under an agreement called the Articles of Confederation, the thirteen American colonies, among them Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware, bound themselves (as sovereign states) into the United States of America in a combined fight against England. Proprietorships granted by England no longer applied. In 1776, concerned about one of the new nation’s boundaries — the one between Virginia (West Virginia did not become a state until 1863) and Pennsylvania — Thomas Jefferson wrote to fellow Virginian and politician Edmund Pendleton, stating, “I wish they would compromise by an extension of Mason & Dixon’s line. They do not agree to the temporary line proposed by our [Virginia] assembly.”

After the Revolutionary War, Mason and Dixon’s line remained the boundary separating the three states, although minor disputes continued over a small wedge of land where the three states converged. During the years 1782 to 1785, several surveyors completed the West Line by extending it to five degrees longitude, bringing the total length of the line to about 260 miles. People of the time were well aware of Mason and Dixon’s line; it became part of everyday language. In 1784, a letter excerpted in the July 7 issue of the newspaper Freeman’s Journal described the approach of a severe storm: “The storm then took across the ridge and made as clear a line as ever Mason and Dixon did.”

During the early decades of the nineteenth century, perceptions of the origin of the Mason-Dixon Line had already blurred. In fact, in the 1830s, a number of newspapers printed short articles that reminded readers of the line’s roots in a dispute between two feuding colonies. They did so because Mason and Dixon’s line had begun to act as a boundary not just between states but between two new identities, and these new perceptions altered the lives of millions of Americans.

As tensions increased between northern and southern states, particularly issues concerning taxation of goods, people increasingly regarded Mason and Dixon’s line as the division between the North and the South — not only geographically but also politically. For the most part, industry and manufacturing drove the North economically. Political decisions supported growth in those areas. In contrast, agriculture, particularly the cotton crop, drove the southern economy. Shipping cotton to overseas markets was big business. Political decisions favored increased crop production, which required increased labor — labor most often supplied by slaves. Slavery, at first on economic grounds, later on moral grounds, became a hotly debated issue as the United States expanded into new territories in the West. Tensions between the North and South escalated. In the June 24, 1833, issue of the Connecticut Courant, a man recalled a conversation he had had with the late John Randolph, a congressman and senator from Roanoke, Virginia. Randolph had been sending books to England for binding. When asked why he didn’t use binderies in New York or Philadelphia, he had replied, “What Sir, patronize our Yankee task-masters who have imposed such a duty upon foreign books! Never, Sir, never! I will neither wear what they make, nor eat what they raise . . . and until I can have my books properly bound south of ‘Mason and Dixon’s line,’ I shall employ John Bull” (meaning England). On October 9, 1841, Terre Haute’s Wabash Courier editorialized, “This famous line is so often mentioned in and out of Congress that to American ears its name is familiar as household words.”

At the same time, Mason and Dixon’s line came to symbolize the boundary between freedom and slavery. This perception of the line may have started when Pennsylvania passed a new law in 1780.

On March 1, 1780, the Pennsylvania legislature passed the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. While it did not set free the many slaves living in the state, it started the process. First, the law required slaveholders to register their slaves with government authorities by November 1, 1780; unregistered slaves would be considered free. The law was not unanimously popular. Slaveholder George Stevenson, who lived in Carlisle, resentfully complied. On October 7, he registered his three male slaves, Dick, Phil, and Mills. On the register, he wrote a comment stating he did so “in obedience to an useless Act of the General Assembly of the Common-Wealth of Pennsylvania, entitled ‘An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery.’ ”

Second, the act declared that a child born of a mother who was a slave would become free when she or he turned twenty-eight years old. Taking advantage of loopholes in the law, some slaveholders avoided freeing younger slaves by selling them out of state before they reached that age or by sending a pregnant woman to another state, where the baby would be born under the slave laws applicable there. In 1788, to stop these evasions of the law, an act was passed that required the birth of an African-American child to be registered with the state government; it also prohibited sending enslaved pregnant women out of state.

At the same time, Quakers who supported abolition on moral and ethical grounds increasingly pressured Quakers who owned slaves to free them. Gradually, they responded. Together, the abolition act and the slaveholders who manumitted their slaves made a huge difference. Between 1780 and 1782, 6,855 slaves lived in Pennsylvania; in 1810, that number had been reduced to 795.

When the Pennsylvania assembly passed the 1780 abolition act, Mason and Dixon’s West Line literally became a boundary line between a free state and a slave state. But the Mason-Dixon Line between Maryland and Delaware — the Tangent Line — was not. Both Maryland and Delaware were slave states. And not all of the states north of Mason and Dixon’s line were free states, either. New York did not begin gradual abolition until 1799; New Jersey began gradual abolition in 1804. (Both states stipulated that children born of mothers who were slaves would be free, but only after serving as indentured servants into their twenties.)

The issue of slave states versus free states persisted as the United States expanded its boundary farther west. Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), and Illinois (1818) were admitted into the union as free states. The Ohio River was and is the southern border of these states. As such, it was a boundary line between these three free states and the slave states of Kentucky and Virginia. (Perhaps because people had come to perceive Mason and Dixon’s line as the boundary between slave and free states, they thought the Ohio River boundary was an extension of the line. But the two surveyors never worked farther west than Browns Hill.) Louisiana (1812), Mississippi (1817), and Alabama (1819) were admitted to the Union as slave states. A huge controversy arose when Missouri petitioned for statehood, because its status would upset the balance of slave and free states, which in 1819 stood at eleven states each. Balance was maintained through the Missouri Compromise, which was enacted in 1820. It allowed Missouri (1821) to enter the union as a slave state and Maine (1820) to do so as a free state. According to the Missouri Compromise, slavery was banned in the vast Louisiana Territory from latitude 36°30′ N, with the exception of the land used to create the state of Missouri. All of the Louisiana Territory was more than 500 miles west of the end of Mason and Dixon’s line. Yet people incorrectly associate the Missouri Compromise with their line.

In 1849, Edward Gorsuch lived near Glencoe, in Baltimore County, Maryland, less than twenty miles south of milepost 44 along the West Line. The Gorsuch family roots ran deep; they’d lived in Maryland since the mid-seventeenth century. Edward Gorsuch had a wife and family. Friends and neighbors reported him to be a dignified, well-mannered man who taught Bible class at the Methodist church. He had inherited his farm of several hundred acres from his uncle, and he cared for it well, growing wheat and corn. He owned cows, sheep, pigs, and chickens. He also owned twelve slaves, a high number considering that only 10 percent of Maryland’s slaveholders owned eight or more slaves. To Gorsuch, everything on the farm — the land, the animals, the slaves — was his property.

In 1849, more free blacks, about 74,700, lived in Maryland than in any other state. But Maryland had an even larger population of slaves, about 90,300. Between June 1849 and June 1850, 279 slaves escaped from Maryland. Four of them — Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Hammond, and Joshua Hammond (whose ages ranged from nineteen to the mid-twenties) — ran away from Edward Gorsuch.

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE ACT OF 1850 was not the first law concerning escaped slaves. Fifty-seven years earlier, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 had required the return of runaway slaves. In the years since then, the issue of whether or not to require the return of escaped slaves had raged even more fiercely between abolitionists and slaveholders. Many abolitionists in northern states where slavery had been abolished completely ignored the 1793 law on the grounds that slavery was not permitted in their state. Southern slave owners demanded a law that would force free states to return their fugitive slaves. The Compromise of 1850 addressed slavery in the West and banned slavery in Washington, D.C. It also included the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which strengthened the earlier act.

Among its many mandates, the new act required that government marshals — even those in free states —“obey and execute all warrants . . . issued under the provisions of this act.” A fine of one thousand dollars was issued if the official refused. Slave owners could obtain a warrant for the slave’s arrest, pursue him or her into the free state or territory to which he or she had fled, and apprehend him or her. The slave owner could also hire an agent to act on his or her behalf. Any person who obstructed or hindered a slave owner, his agent, or any other person lawfully assisting him or her would be fined up to a thousand dollars and be sentenced to up to six months in prison. Furthermore, “In no trial or hearing under this act shall the testimony of such alleged fugitive be admitted in evidence . . . and [the warrant] shall be conclusive of the right of [the slave owner or agent] to remove such fugitive to the State or Territory from which he escaped.” The act drew very specific legal boundaries that outlined the rights of the slaveholder. The fugitive slave was given no rights at all.

The four fugitives’ freedom journey started with wheat. After the autumn harvest was stored, Gorsuch discovered that some of the grain was missing. A Quaker miller told Gorsuch that Abraham Johnson, a free black man who lived nearby, had offered to sell him a number of bushels of wheat. The miller said Johnson had gotten the wheat from four of Gorsuch’s slaves. Gorsuch obtained a state warrant for Abraham Johnson’s arrest. Hearing this, Johnson hid, and later fled north. Meanwhile, the slaves planned their escape. The night of November 6, 1849, the four men, aided by another of Gorsuch’s slaves, made their way north. They crossed the Mason-Dixon Line into Pennsylvania.

Gorsuch could not comprehend why his slaves had left; he felt he had treated them well, and they knew they would be freed at age twenty-eight. He concluded that they had been led astray, and he believed they would return to his farm if given the choice. For nearly two years, Gorsuch followed the rumor trail in the hope of discovering their whereabouts. Finally, in August 1851, he received creditable word from one of his agents, a man named William Padgett, that the men were living in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, near the town of Christiana. At that time, a group of white men called the Gap Gang spied on black people in the area in an attempt to find people who fit the description of fugitive slaves. They alerted slave owners. They terrorized the black community. And they even kidnapped black men and women — making no distinction between a free person of color or a fugitive slave — and took them across the boundary line into Maryland. They justified their actions as upholding the Fugitive Slave Act. Many locals believed that Padgett belonged to the Gap Gang.

Gorsuch assembled an armed posse that included his son Dickinson, a cousin, a nephew, and two neighbors. On September 9, in Philadelphia, under the auspices of the Fugitive Slave Act, he obtained four arrest warrants for his escaped slaves. He arranged to rendezvous with U.S. deputy marshal Henry Kline near Christiana. Two policemen Gorsuch had hired to accompany the posse never showed up.

Before dawn on September 11, 1851, a disguised guide led the posse, who traveled on foot so as not to alert the fugitives, to a road leading to a stone house occupied by tenant farmers William Parker; his wife, Eliza (both of whom had been fugitive slaves); and his in-laws, Alexander and Hannah Pinckney. Gorsuch’s informant had reported that two of his fugitive slaves, living under the assumed names Joshua Kite and Samuel Thompson, were hiding inside Parker’s house. Gorsuch reckoned he would soon have his slaves back under his control. He didn’t know that an informer in the black community saw the posse traveling on the road the previous night and had alerted Parker, a fierce freedom fighter. And he was unaware that freeman Abraham Johnson, the man who had tried to sell Gorsuch’s wheat back in Maryland, was also inside Parker’s house.

William Parker and the other African Americans barricaded on the second floor of his home refused to be intimidated by Edward Gorsuch and Deputy Kline. An argument between Gorsuch and one of the fugitives escalated into a riot.

Parker later stated that as the posse neared the house, it encountered Joshua Kite, who had gone outside. When Kite fled back inside, Kline and Gorsuch followed him in and climbed halfway up the staircase to the second floor.

Parker met them on the landing and told Deputy Kline he would not surrender. Gorsuch, at the bottom of the stairs, told Kline that the law was on his side. Kline agreed and stated that he could arrest the people in Parker’s house. After a short time, someone in Parker’s group threw a fish gig (a pronged instrument used to hook fish) down the stairs, followed by an ax. More discussion followed. According to Parker, Gorsuch said to him, “You have my property,” to which Parker replied, “Go in the room down there, and see if there is anything there belonging to you. There are beds and a bureau, chairs, and other things. Then go out to the barn; there you will find a cow and some hogs. See if any of them are yours.” Gorsuch said, “They are not mine; I want my men. They are here, and I am bound to have them.” The two men held opposite viewpoints: Parker was defending people and their right to freedom; Gorsuch sought to reclaim property.

Sunrise approached. Heated conversation continued. Gorsuch insisted. Parker refused. Deputy Kline hemmed, hawed, and threatened to “set the house on fire, and burn them up.” At that point, Mrs. Parker grabbed a horn used as a signal for help by the black community in a time of trouble. She went to the window and blew it long and loud. A few minutes later, she repeated the call. The horn’s blare brought on a hail of gunfire from the posse. Shouts and calls for further discussion led to a fifteen-minute truce, followed by more talk between Parker and Gorsuch. Parker later claimed that Gorsuch was carrying two pistols; Dickinson Gorsuch said his father was unarmed.

Meanwhile, Castner Hanway and another of Parker’s white neighbors, believing the posse to be kidnappers, hurried to Parker’s house. Both men were well aware the Gap Gang kidnapped African Americans. Hanway asked to see the deputy’s warrants. Even as Hanway read the warrants, members of the black community armed with guns, clubs, corn cutters, and scythes arrived in response to Mrs. Parker’s signal. Later reports as to how many people arrived vary widely, ranging from fifteen to three hundred. Based on the 1850 U.S. census for the number of black people living in the area, a reasonable estimate is about twenty-five.

By the time these men assembled in the orchard in front of Parker’s house, tempers had reached the boiling point. Kline urged the posse to back off; Hanway urged Deputy Kline to leave. The crowd pressed forward. Kline leaped the fence and disappeared into the grain field, but Edward Gorsuch stood resolute. Fugitive Samuel Thompson went outside and argued with Gorsuch. Then he seized Alexander Pinckney’s rifle and clubbed Gorsuch. When Gorsuch rose, Thompson hit him again. And then the shooting started. No one knows who shot first. Chaos reigned. People screamed, shouted, and ran.

The whole confrontation, from first words through the riot that followed, lasted two hours. At the end of that time, Edward Gorsuch — shot, stabbed, and beaten — lay dead in Parker’s front yard. His son Dickinson, seriously wounded by a shotgun blast to his side, lay in the field. Two bullets fired by Dickinson had passed through Parker’s hat and sheared off some hair but had not drawn blood. Two other members of Parker’s party were wounded: one in the hand, the other in the thigh. Gorsuch’s nephew was severely beaten. Quaker Levi Pownall, who owned the Parkers’ house, arrived at the scene and asked Parker for a blanket to cover Edward Gorsuch’s body and for some water to give Dickinson. Parker told him to take anything he needed. Afterward, Pownall took Dickinson to his house. Contrary to everyone’s prediction, Dickinson recovered, although it took many weeks. Edward Gorsuch’s body was shipped by train to his family in Maryland.

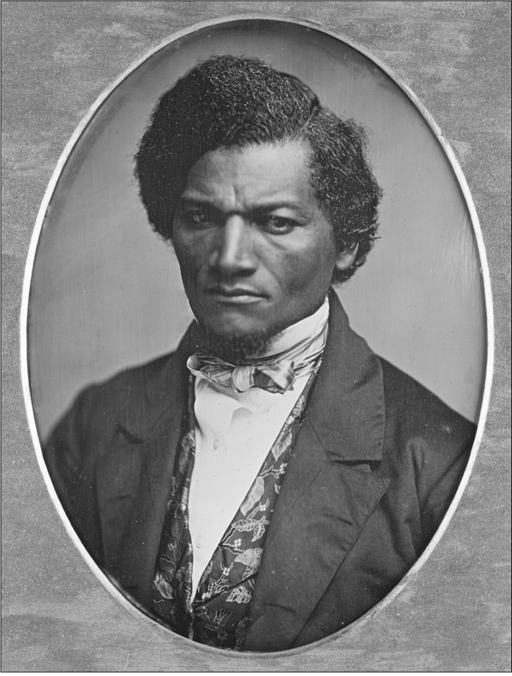

Advised by friends to leave Pennsylvania, William Parker, his brother-in-law Alexander Pinckney, and Abraham Johnson traveled a circuitous four-hundred-mile journey by foot, wagon, and stage to Rochester, New York, where they stayed in the home of well-known abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass. He made arrangements for their safe passage by steamer out of the United States into Canada. By September 21, Parker and the others were safely in Kingston, Ontario.

Three years before the riot, Frederick Douglass, pictured here, said, “I have stood on each side of Mason and Dixon’s line; I have endured the frightful horrors of slavery, and have enjoyed the blessings of freedom.”

In an editorial in his newspaper, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, on September 25, 1851, Douglass addressed the question of Parker’s group and their right to step across the boundary line between slavery and freedom, as well as the boundary line between the law and moral right:

If it be right for any man to resist those who would enslave them, it was right for the men of color at Christiana to resist. . . . For never were there, never can there be more sacred rights to defend than were menaced on this occasion. Life and liberty are the most sacred of all man’s rights.

Douglass escorted Parker, Johnson, and Pinckney to the wharf the day they left for Canada. Remaining with them until the gangplank was being hauled in, Douglass received a last-minute “gift” from Parker: “I shook hands with my friends, received from Parker the revolver that fell from the hand of Gorsuch when he died, presented now as a token of gratitude and a memento of the battle for Liberty at Christiana.” He further added that “this affair, at Christiana, . . . inflicted fatal wounds on the fugitive slave bill.”

Meanwhile, in Christiana, thirty-eight people had been imprisoned in the riot’s aftermath. Many of the black men were arrested with no evidence other than Deputy Kline’s declaration that he recognized them as having been present. A few of his accusations were later proven untrue. On November 24, 1851, the trial of Castner Hanway, the neighbor who urged Kline to leave Parker’s house, began. He was charged with treason against the United States. If he was convicted, the penalty would be death.

For eighteen days, in a courtroom with standing room only, the judge and jury listened as witnesses testified about Hanway’s words and actions on September 11. Before the jury began its deliberations, the judge spoke to its members. He told them they had the right to make their own decision, but that, having heard the facts of the case, he felt bound to offer his opinion, which the jury could take into account or not, as they chose. He said he did not believe there was any proof “of previous conspiracy to make a general and public resistance to any law of the United States.” He further noted that there was no evidence that the persons involved had been aware of the Fugitive Slave Act, or that they “had any other intention than to protect one another from what they termed kidnappers.” The jury left the court for their deliberations. They returned in about ten minutes with their verdict: not guilty. Ultimately, all charges against the Christiana prisoners were dropped.

The national attention showered on the Christiana events forced everyone — both north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line — to think more about the issues of freedom and slavery. It proved that the members of the black community in Lancaster County were not simply victims. They were people who willingly crossed geographical, philosophical, and even legal boundaries to assert their rights as human beings. Especially for them, the Mason-Dixon Line had become a symbol of freedom.

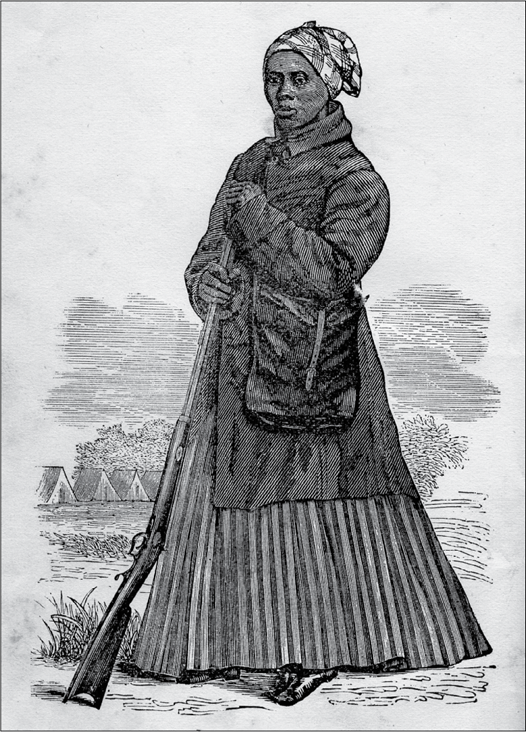

Harriet Tubman, a fugitive slave who risked her life many times leading others to freedom, eloquently stated how she felt when she first crossed the line: “When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over every thing; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

Harriet Tubman guided more than three hundred slaves to freedom.

As a legal boundary between slavery and freedom, Pennsylvania’s 1780 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery rang the early bells of the demise of slavery. Symbolically, Mason and Dixon’s West Line, as a geographical boundary, reinforced the toll. Slaves who challenged the moral boundary of slavery and fought back by escaping rang the bells louder. The Civil War heralded the end to slavery. On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order that freed slaves in “States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States.” The states listed in the proclamation were Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. But the proclamation did not free the slaves who lived south of the Mason-Dixon Line in Maryland or east of it, in Delaware. Both states had remained in the Union (Maryland under governmental force), where the proclamation did not apply. Neither would the proclamation free any of the slaves in the soon-to-be state of West Virginia, which was admitted to the Union in June 1863, with the gradual abolition of slavery already in its laws. Slavery did not officially end in the United States until the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was adopted on December 6, 1865.

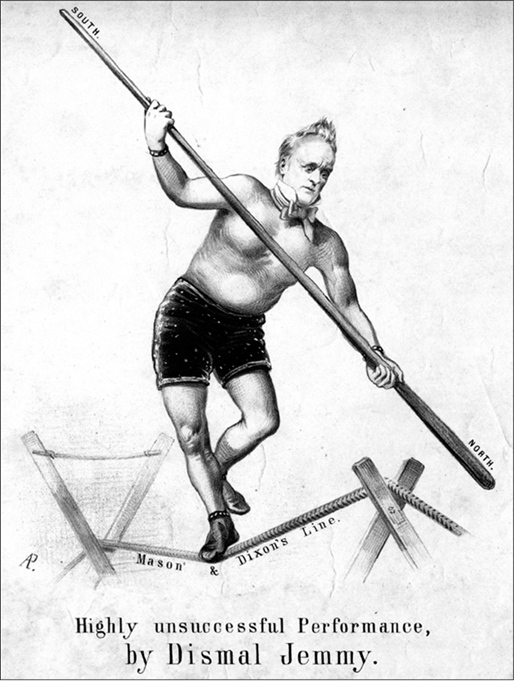

The first person to cross Niagara Falls on a tightrope did so in June 1860. This cartoon parodies President James Buchanan’s unsuccessful attempts to politically balance the many disagreements between the North and the South.

Since then, the Mason-Dixon Line, a reference once found peppering everyday talk, has largely become a topic mentioned only in history books and on highway signs along the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania. But the line has not been completely forgotten, nor should it be.