Despite its large size – its 111,369 sq km (42,999 sq miles) make it second only to Nicaragua in the region – Honduras remains a mystery to many travelers to Central America. Political instability and high crime in recent years has steered what were promising investments in tourism off course, leaving the fate of many projects in the air. Still, no country in the region has more potential.

The Baroque cathedral in Parque Morazán, Tegucigalpa.

AWL Images

This is a country with a profound wealth of fascinating destinations. What it lacks in volcanoes, it makes up for in pine-covered mountains and lush cloud forests, 965km (600 miles) of coastline dotted with resorts and Garífuna villages, and a mini-Amazon with impenetrable jungles.

Copán.

iStock

The sprawling cities of Tegucigalpa, the capital, and San Pedro Sula, the commercial center, are the main points of entry into the country and are home to fine museums and bustling nightlife. They demand no more than brief stops in transit, as to appreciate real Honduras requires you to get away from the often chaotic, sometimes dangerous centers of population.

Most tourism is concentrated in the Bay Islands of Roatán, Utila, and Guanaja, three idyllic little English-speaking Caribbean isles with some of the world’s best – and most inexpensive – diving. They are a place where escaped slaves, pirates, and now a growing number of expats have created a distinct cultural makeup. The North Coast, with its wildlife-rich national parks like Pico Bonito, Spanish forts, and family friendly beach resorts is a close runner up, attracting adventure sports enthusiasts, birdwatchers, and a growing number of North American retirees.

In the interior, there’s the ancient city of Copán, perhaps the most spectacular Mayan ceremonial city in all of Mesoamerica, and the majestic Lago de Yojoa, flanked by two different national parks. Not far away is Comayagua, one of the region’s best preserved colonial cities, and sleepy Gracias, once the capital of Central America and now a jumping off point to explore a string of Lenca villages. Lastly, there’s La Mosquitia, where the thick jungle hides raging rivers, indigenous communities, and the remains of a mysterious civilization that’s slowly being revealed.

The modern economy

Carlos Roberto Flores Facussé became president in 1988 and initiated wide-scale currency reforms to slow the rapid inflation that was sinking the value of the lempira against the dollar. After decades of instability, things were beginning to look up, until Hurricane Mitch, the most powerful Atlantic storm ever recorded at the time, came along in October 1998 and caused billions of dollars worth of damage. More than 6,000 people were killed and 1.5 million displaced in the aftermath. The following years were spent trying to get the country back on its feet and repairing much of the damage. Even today the country’s infrastructure still has not fully recovered.

In 2006, Olancho rancher Manuel Zelaya Rosales was elected president on a platform of doubling the police force and lowering gas prices. The Central America and Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) went into effect not long after, which led to increasing costs for food and energy. Zelaya turned to controversial Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez for help, allowing him to make modest economic and social reforms, like nearly doubling the monthly minimum wage from $157 to $289 and resolving longstanding land conflicts between peasant farmers and agribusinesses. However, his reforms didn’t always go over well, as many factory owners could no longer afford to pay their employees and laid them off.

US intervention

While Honduras somehow avoided political upheaval like its neighbors in the second half of the 20th century, the US military used it as a base for the counter-insurgency movement against the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. Aid was provided to Honduras in exchange for space to train and equip the Contras, though many Hondurans were displeased. Mass protests against the US military broke out, and even as the Honduran military responded by kidnapping and killing protestors, they didn’t lose momentum. In 1988, after it was revealed that the Reagan administration had sold arms to Iran to support the Contras, the government ended its military agreement with the US. By the time the Contra war ended in 1990, the Contras were already gone from the country.

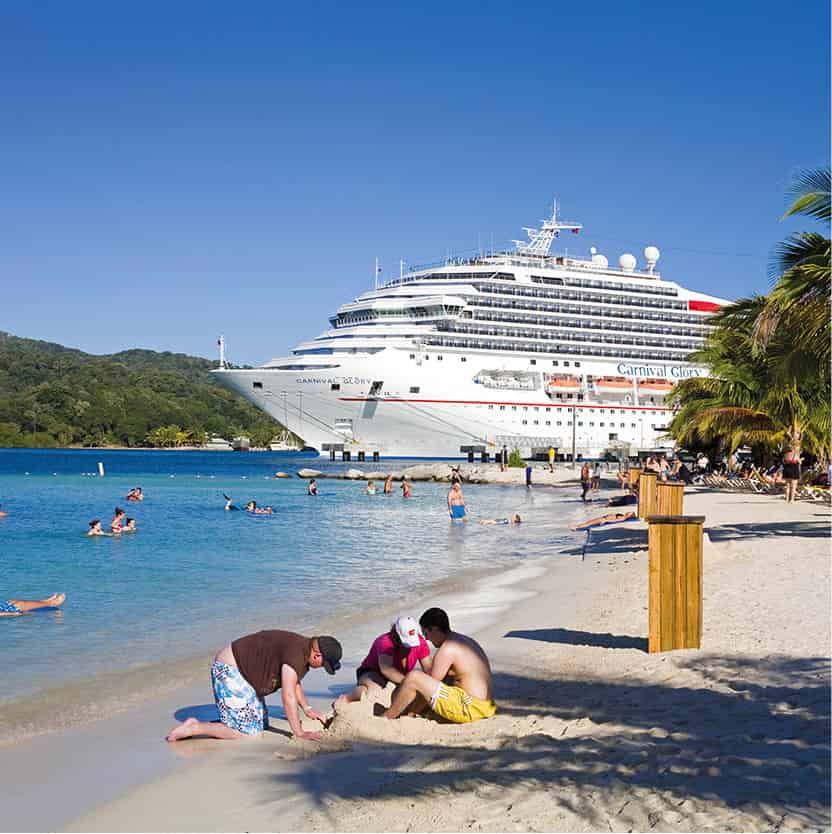

Cruise ship docked at the Mohogany Bay Cruise Center.

Getty Images

Honduras today

Despite low approval ratings, Zelaya called a referendum to reform the constitution and allow presidents to stand for re-election. On June 28, 2009, a few days before the vote was to take place, the army forced him on a plane, still in his pajamas, and took him to Costa Rica. Amid mass protests, a five-month curfew imposed by the new government cost the economy $50 million a day. In the weeks following the coup, Zelaya made three attempts to re-enter the country, but was stopped each time. New elections, boycotted by much of the country and many opposition candidates, took place that November. The right-wing National Party’s Pepe Lobo Sosa took office in January 2010, initiating a series of mining, logging, and agri-business projects, to the dismay of environmentalists.

The coup set the country on a downward spiral from which it is still trying to recover. Wages have dropped, public education and social security systems were destroyed, and tourism took a nose dive. Organized crime began taking advantage of weak institutions. The murder rate surged and by 2010, Honduras had become the world’s most violent country outside of a war zone. The drug trade flourished and it is estimated that 80 percent of cocaine-smuggling flights bound for the US passed through Honduras.

Elected in 2013, current president Juan Orlando Hernández has pushed forward with an overhaul of the country’s political system, creating a new militarized police force and installing figures loyal to his party in the supreme court and congress. Violent crime and government corruption remain serious problems in the country. Nevertheless, after years on the decline, tourism has picked back up as new beach resorts have opened and cruise ship traffic to Roatán has exploded. While development has been uneven at best and Honduras is not going to become the next Costa Rica anytime soon, there’s some hope in the air.

View of Tegucigalpa from above.

AWL Images

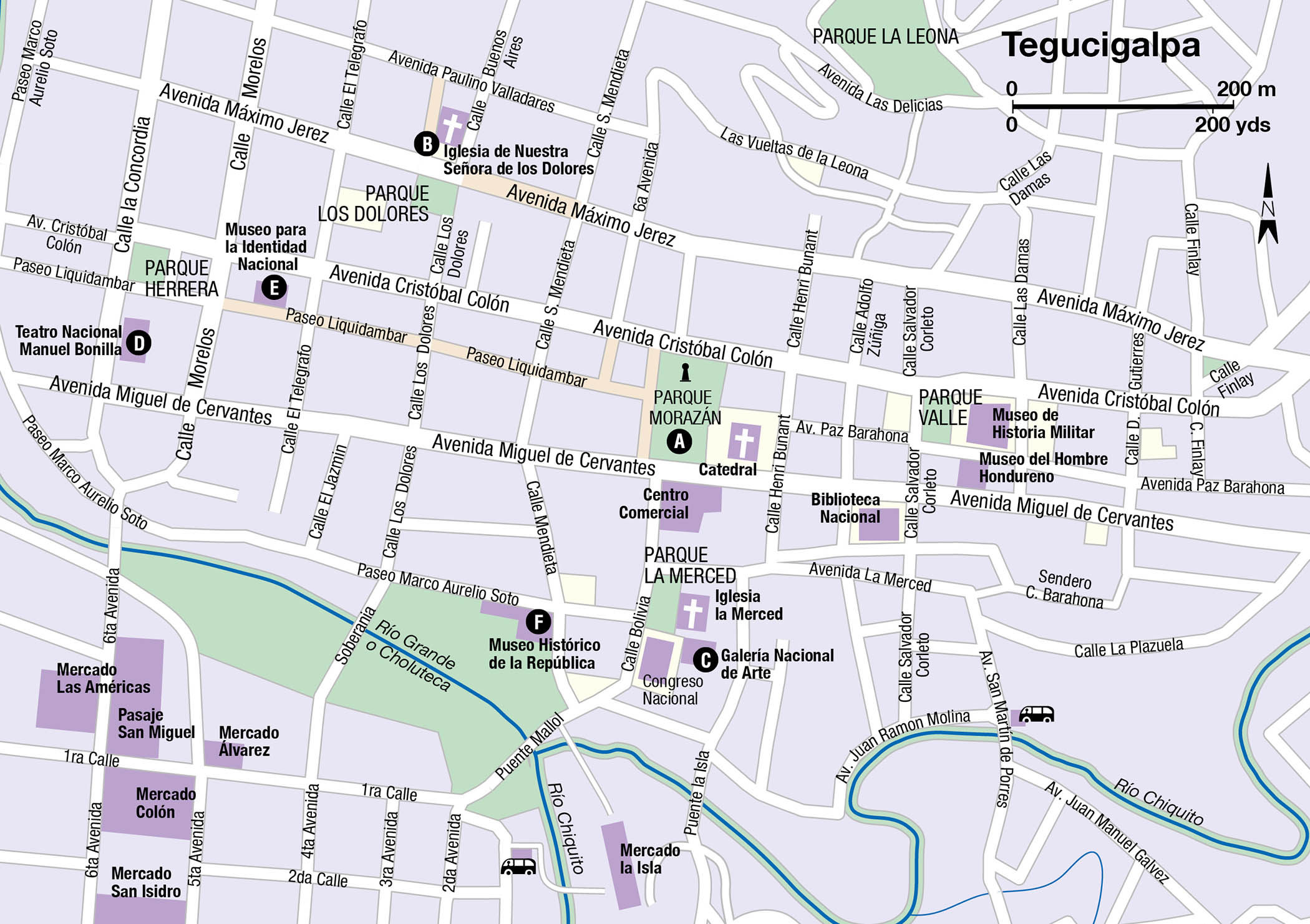

Tegucigalpa and around

Founded on September 29, 1578, Tegucigalpa 1 [map], sitting in a valley surrounded by mineral-rich hills, lingered in obscurity until 1880 when then president Marco Aurelio Soto moved the capital here from Comayagua. While the commercial center of the country has moved to San Pedro Sula, ‘Te-goose,’ as it’s sometimes called, remains the political and intellectual center of the country. While it lacks major attractions, Honduras’ best museums and cultural institutions are found here.

Where

To the southwest of Tegucigalpa, across of the Río Choluteca, is the neighborhood of Comayagüela, which doubled the size of the capital when the cities merged in 1938. While there are still some interesting colonial buildings here, mostly neglected, plus some of the city’s bus terminals, this area can be unsafe and should mostly be avoided.

The city center

The colonial center of Tegucigalpa a grid of 7 by 20 blocks, is at Parque Morazán A [map], or Parque Central. On the square’s eastern edge is a baroque Cathedral, built between 1765 and 1782, that honors Saint Michael the Archangel, while the pedestrian-only Calle Peatonal leads west from the square, sided by clothing stores and inexpensive restaurants. A few blocks northwest is Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores B [map] (daily 7am–noon and 3–6pm; free), dating to 1732 and featuring an impressive carved altar. On a small plaza beside the Iglesia la Merced is the Galería Nacional de Arte C [map] (tel: 2222 0250; www.galerianacionaldeartehonduras.org; Mon–Sat 8.30am–4.30pm, Sun 9am–3pm), Honduras’ most important art museum. The museum, housed in a former convent, displays exhibits chronologically, from the art of pre-Mayan cultures to the religious art of the colonial period and modern paintings from contemporary artists like Pablo Zelaya Sierra.

At Parque Herrera, there’s the stunning Teatro Nacional Manuel Bonilla D [map] (tel: 2222 4366), which was modeled on Paris’ Plaza Athenée. The finest performing arts in the country, from opera to the ballet, are staged here throughout the year. Just up Avenida Barahona is the Museo para la Identidad Nacional E [map] (tel: 2238 7412; www.min.hn; Tue–Sat 9am–5pm, Sun 11am–5pm), which opened in 2006 in what was previously the Palace of Ministries. Honduran history is laid out from its pre-Columbian origins to modern times though photos, historical documents, and artifacts.

On Paseo Soto, inside the former Presidential palace, is the Museo Histórico de la República F [map] (Mon–Fri 8am–4pm, Sat–Sun 9am–4pm), which focuses on the independence era, with exhibitions displaying portraits, documents, and other paraphernalia of past presidents.

Not a residential area and lacking hotels, the center seems deserted after dark and is best avoided.

Outside the center

The rest of the city spreads out to the south and east. Along Boulevard Morazán is Colonia Palmira and Colonia San Carlos, middle- and upper-class residential communities where many of the best hotels and restaurants can be found. Most tourist amenities such as embassies, airline offices, and travel agencies are located here as well. Near the boulevards of Juan Pablo II and Suyapa is the most modern part of the city, where many upscale residents live. The Multiplaza Mall complex, a North American-style shopping complex with international chain stores, is beside top hotels like the Intercontinental.

Farther east is Suyapa, a small town that was swallowed whole by Tegucigalpa’s urban sprawl. Most tourists come here to visit the Santuario Nacional and Basílica de Suyapa (grounds open daily, interior of the basilica only during mass) the largest cathedral in the country. At this gothic cathedral, the Virgin of Suyapa, famous throughout Honduras for its healing powers, is brought out for special events like the Feria de la Virgen de Suyapa.

Equestrian statue of Franscisco Morazán in Plaza Morazán.

Robert Harding

Parque Nacional La Tigra

Twenty-two kilometers (14 miles) from Tegucigalpa is Parque Nacional La Tigra 2 [map] (daily 8am–5pm), a 238 sq km (92 sq miles) tract of cloud forest that has been a national park since 1982. While much of the forest was cut down by loggers and the El Rosario Mining Company, it is slowly being recovered. Hiking trails run through the park, mostly from the western entrance at Jutiapa, where there is a small campground, cabins, and a visitor center. The 6km (3.7 miles) Sendero Principal is the primary route across La Tigra, though a handful of other trails in various states of maintenance branch off it. Even though the park is so close to Tegucigalpa, it has a surprisingly rich collection of flora and fauna. Mammals like pumas and armadillos are rare, though more than 350 species of birds have been identified, including the resplendent quetzal and wine-throated hummingbird. The non-profit Amitigra (tel: 504 232 6771; www.amitigra.org) controls access to the park and can help make arrangements for visiting.

The charming streets of Valle de Ángeles.

Shutterstock

Valle de Ángeles and Santa Lucía

On weekends, day trippers from Tegucigalpa head to a pair of colonial mountain villages east of the city. The first you will come to is Santa Lucía, where small rural inns, country restaurants, and nurseries are strung out along the road. Valle de Ángeles, 8km (5 miles) east of Santa Lucía, has a cooler climate and many wealthy capitalinos have houses here. The 16th-century village is filled with artesania shops selling items from every part of Honduras. While most items are from elsewhere in the country, jewelry made from silver and other metals that once came from the area’s mines are made locally. You’ll find better prices and variety here than in Tegucigalpa. There’s a good hike through the pine forests to the Las Golondrinas Waterfall, about 1km (0.6 miles) outside of town on the road to San Juancito.

Fact

The Lenca are the ancestors of Chibcha-speaking indigenous Americans who came from Colombia and Venezuela more than 3,000 years ago. Today they number around 100,000 in Honduras and about 40,000 in El Salvador.

Western Honduras

For many, the mountainous western region of Honduras is the real Honduras. As you move away from the urban sprawl of San Pedro Sula, cowboys and indigenous groups like the Lenca and Chortí Maya have learned to coexist amidst the pine covered hills. Much of the cigar industry is based here, near Santa Rosa de Copán, and must see attractions like the ruins of Copán, the intellectual capital of the Mayas, and the breathtaking Lago de Yojoa, are here too.

San Pedro Sula

Many travelers tend to skip San Pedro Sula 3 [map], the economic and transportation hub of Honduras, especially given its violent reputation of recent years. San Pedro lacks a connection to the past in the way Tegucigalpa does, as it lingered as a rural backwater until the 1920s when the United Fruit Company set up here. Today the population is around 500,000, making it the second largest conurbation in the country.

The country’s busiest airport is well outside of town and therefore many don’t even get a glimpse of the rather laid-back city center and all of the amenities it holds. The core of San Pedro Sula lies within the Circunvalación, a beltway lined with flashy malls, international chain hotels, and fast food restaurants that give it the feel of a typical American city. In the very center of the Circunvalación is Parque Central, a rather quaint main square surrounded by restaurants and store. A few blocks to the north is the Museo de Antropologia e Historia de San Pedro Sula (tel: 2557 1874; Mon, Wed–Sat 9am–4pm, Sun 9am–3pm), which has a chronological display of the region’s history from pre-Columbian times to the modern era.

Farther north is the sprawling Mercado Guamilito (daily 10am–5pm) an excellent destination for exotic produce and handicrafts from all of the country, like Garífuna coconut carvings, Lenca pottery, and hammocks. Don’t miss the row of stands with women making tortillas and baleadas (a popular Honduran tortilla dish, folded in half and filled with mashed fried beans) by hand; a great photo opportunity.

Boat on Lago de Yojoa.

Robert Harding

Lago de Yojoa

Surrounded by misty pine-covered mountains and coffee fincas, the 89 sq km (55 sq mile) Lago de Yojoa 4 [map] is a premier eco-destination that somehow isn’t swarming with tourists. It’s the country’s largest natural lake and a hotspot for birders who come from around the world hoping to glimpse some of the 400 or so species that have been identified here. Along the lakeshore are several fine hotels, which mostly attract Honduran families, and even a small craft brewery, the American owned D&D (http://ddbrewery.com), which also runs guided boat excursions on the lake. Along the highway bordering the lake are dozens of fish restaurants, selling freshwater fish that are fried whole and served with patacones (fried plantain).

On the lake’s northern edge, 3km (1.9 miles) from the town of Peña Blanca, is Parque Eco-Archeological de Los Naranjos 5 [map] (daily 8am–4pm), a Lenca archeological site that dates back to approximately 700 BC. More interesting than the few mounds and piles of stones there are the 6km (4 miles) of stone paths, trails and observation towers scattered throughout the site where you can observe birds and other wildlife. A small museum and visitor center is at the entrance.

Covering 478 sq km (297 sq miles) along the rugged eastern side of the lake is Parque Nacional Cerro Azul Meámbar 6 [map]. The forested landscape rises to a height of 2,047m (6,714ft) and is quite pristine with waterfalls and elfin forests. Several hundred bird species have been identified here, including keel-billed toucans and resplendent quetzals. As few humans reach the higher altitudes, larger mammals like monkeys, jaguars and tapirs thrive here, though are not easily seen. There are three primary trails ranging from 1.2km (0.75 mile) to 8km (5 miles) that extend from the visitor center in Los Pinos. Guides can be hired at the visitor center.

Near San Buenaventura, about 10km (6 miles) from Peña Blanca, are the 43m (141ft) high Pulhapanzak Falls (daily 6am–6pm) on the Río Amapa. While few tourists visit, these thundering falls are plastered on tourism posters all over the country.

Fact

The route from Lago de Yojoa to Copán is lined with quaint, colonial mountain villages and stands selling junco handicrafts. Many of the villages were founded in the 18th century by Jewish settlers from Spain, Marranos who were escaping religious persecution.

Comayagua

The capital of Honduras for more than three centuries before being moved to Tegucigalpa, Comayagua 7 [map], 71km (45 miles) south of Lago de Yojoa, has the best-preserved colonial architecture in the country. Founded in 1537 by the Spanish explorer Alonso de Cáceres, much of the original city grid remains, along with palaces, churches, and squares

At the north end of Parque Central, the Catedral de Santa María (tel: 2772 7672; daily 8am–6pm; free), dates to the late 17th century and is a masterpiece of colonial architecture. Four of the original 16 hand-carved wooden altars have been immaculately maintained. Outside in the tower, the clock dates to around 1100 and was built for the Alhambra in Granada, but given to Comayagua by King Phillip III. It was originally was placed in the Iglesia La Merced (daily 8am–6pm; free), four blocks to the south and the oldest church in Comayagua. It was built in 1550, but badly damaged in a 1774 earthquake and is partially reconstructed. Set in a 1558 building that once housed Central America’s very first university, the Museo Colonial de Arte (tel: 2772 0386; daily 8am–4pm) maintains a collection of religious art and artifacts that have been created or donated to the city over the past five centuries.

Gran Plaza, Copán.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Fact

During Comayagua’s Semana Santa, or Holy Week celebration, colorful sawdust carpets called alfombras are created by families, social organizations, and church groups and then during the Via Crucis Procession, they are trampled on and swept away.

Near the Guatamalan border is the Maya ceremonial city of Copán 8 [map] (daily 8am–4pm). The area around the ruins has been inhabited since at least 1400 BC. There were 16 consecutive kings who saw the rise and fall of the city, beginning with the Great Sun Lord Quetzal Macaw in 426 AD, as the history carved into the stone dictates. Adventurer John L. Stephens discovered the ruins in 1839, as described in his book Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan (1841).

The town of Copán Ruínas is about 1km (0.6 mile) from the archeological site. Tourism runs the town and within a few blocks of the cobblestone plaza are dozens of small hotels, ex-pat restaurants, and handicraft shops. There are few attractions in town, other than the small Museo Regional de Arqueología (tel: 2651 4108; daily 8am–4pm), aka the Copán Museum, with some pottery and artifacts from the ruins.

On entering the grounds of the archeological site, a path leads to the claustrophobic Rosalia and Jaguar tunnels, which partially opened to the public in 1999 and are subject to an additional fee beyond regular park admission. The tunnels give an idea of how the Maya layered construction, building one temple over another. The trail continues to the Acropolis and Temple of Inscriptions. On the Great Plaza, diagonal from the Temple of Inscriptions, is where the city’s most important symbol can be found: the Hieroglyphic Stairway. Built by King Smoke Shell, the stairway features 64 steps, each carved with hieroglyphs that recount the history of Copán’s kings and their line of succession. Many of the carvings have faded and the necessary covering makes them difficult to make out, though collectively they read like a giant book. Carved stelae, originals, and replicas, beside the stairs depict various rulers and mythical beasts.

Near the main entrance is the Museum of Maya Sculpture, which contains some of the most important stelae and carvings found at the archeological site. At the center of the museum is a full-scale replica of the Rosalia Temple. The museum also contains the reconstructed original facade of one of Copán’s ball courts. Admission is included with your ticket to the park. The Copán Guides Association has a booth near the entrance, where bilingual guides offer 2-hour tours of the site.

About 2km (1.2 miles) from the main archeological site, Las Sepulturas was a residential area for Copán’s ruling elite. It was once connected to the Great Plaza by a broad path causeway, identified by NASA through satellite imaging, though it’s now reached on a leafy jungle trail. Admission is included.

Mayan Rosalila temple replica at the Museum of Maya Sculpture.

Robert Harding

Tip

Around 24km (15 miles) from Copán over rough mountain roads is the Luna Jaguar Spa Resort (www.lunajaguarspa.com), a lovely hot springs facility with a dozen or so pools and bubbling streams amidst thick rainforest. Their massage rooms are found in the Acropolis, a thatched-roof building overlooking a waterfall.

Outside of Copán

Outside of town are forest-covered mountains hiding waterfalls and hot springs, plus superb birdwatching and other attractions. On the road to the border is Alas Encantadas (daily 8am–4.30pm), a butterfly garden and breeding project, plus a botanical garden with more than 200 species of orchids.

There are a few carvings of frogs and the figure of a pregnant woman at a small site called Los Sapos (daily 9am–5pm), across the river from Copán near the excellent country inn, Hacienda San Lucas (www.haciendasanlucas.com), which is known for its multicourse dinners using native techniques and ingredients. Several agencies in town offer horseback-riding tours here.

La Entrada and El Puente

At the intersection of highways CA 4 and CA 11, La Entrada 9 [map] is an otherwise uninteresting town that you would bypass if it weren’t for one spectacular attraction: El Puente (daily 8am–4pm). The ruins, 10km (7.5 miles) out of town, are of a Mayan city built between the 6th and 9th centuries and it is Honduras’ second most important archaeological site after Copán. Still, few actually visit it outside of the occasional tour bus. Several hundred stone buildings are scattered around the park and only a fraction have been excavated. There’s a small visitor center and museum at the entrance, from where it’s a walk of about a kilometer (a half mile) to the site’s primary attraction, a rather large pyramid.

Gracias

For a short time, the sleepy colonial village of Gracias a Dios – named after conquistador Juan de Chavez’s reaction after finding flat land after weeks in the mountains – was the capital of all of Central America. Eight years after being founded in 1536, Gracias ) [map] was home to the Spanish Royal courthouse with a jurisdiction that extended from Mexico to Panama. Four years later the court moved to Antigua and everyone forgot about Gracias for centuries.

Today, with nearby Lenca villages and national parks luring visitors, the town has been capitalizing on its stock of 500-year-old churches and cobblestone plazas. Much of the original Spanish grid, topped by a small fortification on a hillside called El Fuerte de San Cristóbal, has been reconstructed, with boutique hotels and cafés filling the whitewashed houses. Once the home of a wealthy colonial family, Museo Casa Galeano (daily 9am–6pm) is a restored colonial house from the 1840s stocked with artifacts, old photographs, and a folk art collection. It’s adjoined by a botanical garden, one of the oldest in the region.

The Balneario Aguas Termales (daily 8am–8pm), 6.5km (4 miles) south of Gracias, is a public hot springs amenity popular with locals and tourists alike. Surrounded by pine forests, the pools range from 33–35.5ºC (92–96ºF) and are relatively quiet outside of the weekend rush.

La Ruta Lenca

A string of Lenca villages outside of the highland town of Gracias, each with an impressive colonial era church, have banded together to market themselves as La Ruta Lenca. Surrounding Celaque National Park, a circuit pieced together by mostly rough, unpaved roads connects the mountain villages of La Campa, Belén Gualcho, San Manuel de Colohete, San Sebastián, Corquín, and Mohaga. In each town you are rewarded with an unspoiled adobe village where an artisan or two specializes in Lenca crafts, such as the iconic black and white earthenware ceramics. Sundays are the best day of the week to come, when families come to town to sell produce and socialize, and churches are open. In La Campa, one of the first villages, the Centro de Interpretation de Alfarería Lenca (daily 8am–4.30pm) gives some background on the significance on Lenca pottery, especially the giant urns called cántaros that the village is known for. From La Campa the road gets too rough to drive without a 4x4 and slowly winds its way to a fork. Take the road to San Manuel de Colohete, where you’ll find the area’s most impressive church, with a facade from 1721 and frescoes and altars that date back more than 400 years. A lively outdoor market is held on the 1st and 15th of every month (6am–noon).

Parque Nacional Montaña de Celaque

One of the largest tracts of cloud forest remaining in Central America, Parque Nacional Montaña de Celaque ! [map] is the birthplace of 11 rivers that supply freshwater to villages as far away as El Salvador. Hidden within its pines and endless fog are resplendent quetzals, ocelots, and all sorts of rare flora and fauna. It’s not easy though. The trails through the park are rather steep and are often muddy. The difficult hike up the mountain of Cerro El Gallo takes about 3 or 4 hours, while other trails lead to waterfalls and mountain lakes. For the summit of Cerro de las Minas, the tallest peak in Honduras at 2,849m (9,344ft), camping on the mountain is essential for at least one night, with a guided hike requiring at least 2 days. Tour agencies lead guided excursions into the park, though some trails can be hiked independently.

Boats moored up on Tela’s shores.

SuperStock

Northern Honduras

With smart new beach resorts in Tela Bay and a growing number of North American retirees settling down, the North Coast has a sense of momentum that hasn’t been around since Standard Fruit entered the area. There are several important national parks, a good highway and all around good infrastructure, while away from the zipline tours, Garífuna villages and Spanish forts remain to be discovered.

Tela

Conquistador Cristóbal de Olid founded the city of Triunfo de la Cruz on May 3, 1524, though its name was eventually shortened to just Tela @ [map]. Beginning in the early 1800s, the Garífuna came from Roatán and began settling here; many of their communities can still be found all around Tela Bay. For much of the 20th century, Tela was a company town, formed around the banana plantations of the Tela Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company. When operations moved to La Lima in 1976, Tela took a hit. It wasn’t until the start of the next century, when plans were introduced to turn the bay into the next Cancún. Efforts were made to clean up the city and roads were paved through fragile ecosystems to the dismay of many environmentalists. The megaproject is still not fully developed and may never fully materialize, though a golf course and one luxury resort has opened.

Split in two by the Tela River, the city center is on the southernmost point of Tela Bay. Tela Veija, a small colonial grid with most city amenities, is to the east, while Tela Nueva, where the old Tela Railroad buildings and Telamar Resort (www.telamarresort.com), a hotel created from the skeletal remains of company houses, are to the west.

Roughly 5km (3.1 miles) north of Tela is the Jardín Botánico Lancetilla £ [map] (www.lancetilla.org; daily 7.30am–3pm), one of the world’s largest and most important botanical gardens. Established in 1926 by American botanist William Popenoe, Lancetilla was created so he could help United Fruit research and test new varieties of fruit, as well as treat diseases in the plantations. He brought in plants from all around the world, including the African Palm, which would eventually become a major cash crop, albeit a destructive one. The Honduran government took control in 1974 and now manages research here. From the visitor center, trails lead through the 1,680-hectare (4,151-acre) park, passing a large bamboo forest and hundreds of varieties of palms and fruit trees. Many visitors who come here are birders, taking advantage of the estimated 400 species that can be spotted, including trogons and toucans.

Tropical paradise on Cocalto Beach in Parque National Jeanette Kawas.

Robert Harding

Outside of Tela

On the outskirts of the city around the bay are a string of traditional Garífuna communities, such as Triunfo de la Cruz to the east and Tornabé, San Juan, La Ensenada, Río Tinto, and lastly Miami to the west. Tensions have risen in these communities as the resort project as has been seen as a threat to their way of life; however, many are now employed by the resort. Miami, on a sandbar between a lagoon and the ocean, is the most interesting. It lacks running water and the residents still live in thatched huts, much in the same way they have for the last 200 years. For a small fee, local boatmen can paddle visitors out on dugout canoes or ride in motorized boats into the mangroves. The beach area is also quite pleasant and informal restaurants can prepare simple meals just off the sand.

Originally called Punta Sal, the 782km (484 miles) Parque Nacional Jeannette Kawas $ [map] was renamed after the environmental activist Jeannette Kawas Fernández, who was killed after establishing the park. Two distinct ecosystems are found here: the lagoon and the peninsula. Protecting the bay from strong winds called nortes, the peninsula is home to a combination of unspoiled coral reefs, dense jungle filled with howler monkeys, and stunning beaches. Los Micos Lagoon is separated by a small sandbar near Miami, and canals here weave through the rich landscape where hundreds of species of migratory birds can be seen. Outside of driving to Miami and hiring a boat to enter the lagoon, private transportation here is difficult. It’s recommended to use a Tela-based tour operators like Garífuna Tours (www.garifunatours.com), which have regular trips to the lagoon and peninsula.

On the opposite end of Tela Bay is Punta Izopo, where the Lean and Hicaque rivers flow into the ocean amidst thick mangrove forests. Caimans, manatees, monkeys, and hundreds of species of birds can be seen. Kayak trips here are offered by Garifuna Tours, otherwise boatmen in the village of Triunfo de la Cruz west of the park will negotiate trips.

Garífuna people on the beach near La Ceiba.

Getty Images

La Ceiba

The transportation hub of the North Coast is La Ceiba % [map], the capital of the department of Atlántida. Fronting the Caribbean Sea and backed by the jagged mountains of Pico Bonito National Park, Honduras’ third largest city sprawls out along Highway CA-13, where Americanized malls and fast-food chains have firmly entrenched themselves. Two main avenues, San Isidro and 14 de Julio, run parallel to the beach and the city center, surrounding a leafy Parque Central, is not entirely without charm. Barrio La Isla, to the northeast is where you will find the Zona Viva, where the city’s best hotels, restaurants, and nightlife can be found. The city’s beaches tend to be polluted, so it’s best to go to the Playa de Peru east of the pier, or better yet outside of town, for bathing. More than a destination within itself, La Ceiba is better used as a jumping off point to explore nearby national parks or to catch flights and ferries to the Bay Islands.

Protecting the estuary of the Cuero, Salado, and San Juan rivers, the Cuero y Salado National Wildlife Refuge (daily 6.30am–6pm) is 30km (18 miles) west of La Ceiba. Rich with flora and fauna, sloths, otters, and white-faced monkeys, inhabit this mangrove ecosystem, best explored by boat from the visitor center at Salado Barra, where there is a café and dorm amenities. Omega Tours (www.omegatours.info) runs wildlife focused trips here that include about two hours on a boat plus transportation.

Pico Bonito National Park

La Ceiba’s crown jewel is the 100,000-hectare (247,105-acre) Parque Nacional Pico Bonito ^ [map]. Ranging in altitude from sea level to more than 2,000m (6,500ft), there’s more biodiversity here than in any other natural reserve in Honduras. Seven different ecosystems can be found within the park, which contain large tracts of virgin rainforest and cloud forest, not to mention waterfalls and rivers. The range of species living here is staggering. Big cats like jaguars and pumas can be found in more remote corners of the park, though there are also tapirs, several species of monkeys, and hundreds of species of birds, butterflies, and reptiles.

The park is divided into two parts. On one side is The Lodge at Pico Bonito (www.picobonito.com), an upscale ecolodge that regularly ranks among the world’s best, with a gourmet restaurant and highly trained guides. From the lodge, guests and non-guests who come on day trips can access a network of immaculately maintained trails, bird-watching towers and swimming holes in the Coloradito River. A butterfly sanctuary and serpentarium can also be found on the grounds. The other section of the park is along the buffer zone of the park at the Cangrejal River, up the mountain from the village of Las Mangas, west of La Ceiba, just beyond Sambo Creek. Upon crossing a hanging bridge over the river, there is one primary trail that leads to the 60 meter (196ft) El Bejuco Waterfall. This section of the park is more active, with a dozen or so small ecolodges. Adventure tour operators like Jungle River Tours (www.jungleriverlodge.com) set up rafting trips on the Class II-V Cangrejal that pass through pristine forests and over giant granite boulders.

Chachahuate Cay on Cayos Cochinos is a Garífuna community.

Shutterstock

Also known as the Hog Islands, the Cayos Cochinos & [map] are a cluster of tropical islands, cartoonish coral cays, and sandbars 30km (19 miles) northeast of La Ceiba. Part of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, there are strict conservation rules, such as no commercial fishing within the 489 sq km (189 sq miles) reserve. The reef here, with 60 or so dive sites, is as good, if not better, than any you will find in the Bay Islands and includes walls, drifts and small wrecks. There are good chances of seeing manta rays, bottlenose dolphins, whale sharks, and hawksbill turtles. The two main islands, Cayo Menor and Cayo Mayor, provide accommodations in a small hotel and a few private homes, plus a hiking trail, and a research station. The only permanent settlement belongs to the Garífuna community of Chachauate Cay, which lacks running water and electricity. Here, small restaurants serve typical dishes to day-trippers and rent out hammock space for those that want to stay longer.

Trujillo

At the end of the north coast highway CA-13, 165km (102 miles) east of La Ceiba, is the town of Trujillo * [map]. It was here, on August 14, 1502, that Christopher Columbus – on his fourth and final voyage – set foot on the American mainland for the first time. There have long been rumblings about turning Trujillo into a major beach and cruise destination, and with its wide beaches and unspoiled forests it still might achieve its potential, but since Hurricane Mitch hit in 1998 and caused considerable damage, those plans have been on hold.

The colonial center of town is on a hilltop, guarded by a row of canons at the Santa Bárbara fort (daily 8am–noon, 1–4pm), erected in the 17th century to guard against pirate attacks. There is a small museum with muskets and other relics from British rule on display. One of the only other attractions in town is the old cemetery, where the three-centuries-old graves are usually overgrown with weeds. The most notable grave belongs to American adventurer William Walker, who, after a failed attempt of taking over Costa Rica, fled to Trujillo and took over the fort before surrendering to Honduran authorities and being swiftly executed.

Unpaved roads from the town along the coast lead to the Garífuna communities of Santa Fe and Guadalupe. Santa Fe, 12km (8 miles) to the west, has some nice beaches and Comedor Caballero, better known as Pete’s Place, a traditional Garífuna restaurant with some of the best seafood on the North Coast.

The 4,500-hectare (11,119-acre) Capiro y Calentura National Park, occupying the mountainous jungle behind Trujillo, has very little infrastructure and is understaffed. A dirt path on the southern end of town will lead to the Calentura mountain summit in about three hours.

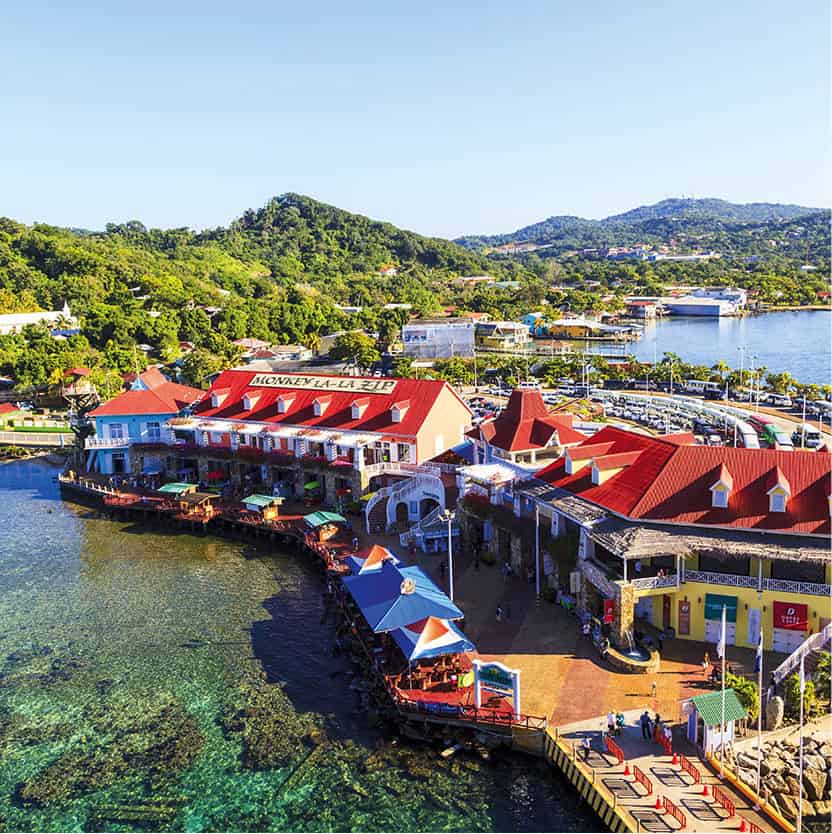

Roatán Port.

Shutterstock

For several centuries, as the Spanish raided the New World for gold, the Bay Islands were used as hideouts for French and English pirates, including famous buccaneers like Henry Morgan and John Coxen. After war broke out between England and Spain in 1739 the British took control of the islands and set up forts at Port Royal in Roatán; however, battles until the end of the 18th century left the islands uninhabited. At Punta Gorda in 1797, the British dumped a few thousand Garífuna, many of whom settled on the east end, where their culture is widely celebrated. New waves of settlers arrived from the Caymans in the following centuries and, even though Honduras was granted sovereignty to the islands in 1859, there is a completely different air than on the mainland.

Roatán

Most tourism to the islands rotates around Roatán ( [map], the largest of the Bay Islands at 64km long (40-mile). It’s here that the cruise industry has sunk about $100 million into modern ports, Mahogany Bay and the Port of Roatán’s Town Center, which have attracted waves of oversized cruise ships that come to the island as part of longer Caribbean itineraries. When cruise ships are in town, much of the island loses its charm, filling roads with tour buses and crowding West Bay beach.

Most development has taken place on the Western half of the island. The crystal clear waters of West Bay Beach, the best in Honduras, has seen a surge in development over the past decade and resorts and condo projects have bought up every last hectare. In the hills above West Bay is Gumbalimba Park (www.gumbalimbapark.com; daily 8am–4pm) an island adventure park with watersports, a monkey island, and a canopy tour that’s often visited by cruise travelers. West End, reached by road or water taxi from West Bay, is the older center of tourism here and the main hangout for the dive community. Hotels are smaller and less polished here than in West Bay and many of the restaurants and bars are owned by expats.

Sandy Bay is dominated by the all-inclusive resort at Anthony’s Key (www.anthonyskey.com), which is set up on the shore and an adjoining cay. At attached Bailey’s Key, operated by the Roatán Institute for Marine Sciences, there is a dolphin encounter and dolphin training program. Carambola Gardens (www.carambolagardens.com), also in Sandy Bay, has several trails that weave through the island’s native flora and fauna.

Coxen Hole, in the center of the island, is home to the majority of the population and is the transportation hub of Roatán. Aside from cruise tourists arriving at the nearby Port of Roatán, there’s little reason to come here. Mahogany Bay, the other cruise port, which was formerly known as Dixon’s Cove, has a white sand beach, but it’s still not West Bay.

The town of French Harbour was once the home of the island’s fishing fleet, but now the marinas are filled with yachts and the town filled with expats. It’s more of a residential area, though there’s one large resort, Pristine Bay (www.pristinebayresort.com), with the Pete Dye-designed Black Pearl golf course.

Connected along the coast through canals, the eastern towns of Oakridge and Jonesville are mostly Afro-Antillean, with people residing in traditional-style stilt houses. Boatmen line the road offering short tours through the mangroves, stopping at the famous restaurant Hole in the Wall, reached only by boat. Punta Gorda, where the paved road ends, is where the Garífuna first arrived from St. Vincent in 1797, though there is little beyond here other than the excellent beaches of Camp Bay and Paya Bay, which has a small resort (www.payabay.com).

Divers off Roatán.

iStock

Diving in the Bay Islands

With easy access to the world’s second largest barrier reef, the Bay Islands of Roatán, Utila, and Guanaja, not forgetting Barbareta and 60 or so other cays, are best known for diving. Nearly every hotel and resort found on these mostly English speaking islands offers some form of dive package. Aside from the low prices for certification courses, what makes the Bay Islands such a famous place for scuba diving? It’s the variety of dive sites you can find just off shore of the three islands. On Roatán there are wrecks, like the intentionally sunk 100-meter (300ft) Odyssey, the reef sharks that get together in the deep waters at Cara a Cara Point and dramatic crevices like Mary’s Place where the sunlight can hit at just the right angle that it becomes illuminated. On Utila, Duppy Waters is home to huge barrel sponges, while whale sharks on the north bank of the island almost year round. On Guanaja, the Pinnacle offers gorgonian and black coral where seahorses like to play and the Jado Trader, a freighter wreck that is one of the region’s best artificial reefs.

Utila

Despite being the smallest of the Bay Islands, Utila , [map] might be the most interesting. It’s not really a beach island, though there are a few sandy stretches. There are no large settlements other than East Harbour, where the ferries dock. Residents are mostly descendants of pirates and Garinagu from the Caymans, plus a mix of expats who came diving here and just never left. Much of the island is covered by mangroves and there are even tales that Captain Morgan buried treasure from a 1671 raid in Panama somewhere in the hills.

There are two beaches within walking distance from town, Bando Beach, which is privately owned and rents snorkel and kayak gear, and Chepes Beach near Sandy Bay. For a more paradisiacal experience, there’s Water Cay, essentially a sand bar with a few palm trees, ringed by turquoise water.

Diving here is spectacular and prices for dives and certification courses are lower than almost anywhere. Dive shops like Utila Dive Center (www.utiladivecenter.com) and the Bay Islands College of Diving (www.dive-utila.com), line the main drag in East Harbour and every hotel can help set you up with an all-inclusive rate. There are nearly 100 permanent mooring buoys that give access to various reefs and wrecks within a short boat ride of the shore. Whale sharks are commonly seen in March and April and most dive shops will run snorkeling trips.

Enjoying the sunset from a waterfront dock in Útila.

Getty Images

Guanaja

On July 30, 1502, Christopher Columbus landed on Guanaja ⁄ [map], 12km (7 miles) east of Roatán and the least developed of the Bay Islands. Like Utila, Guanaja was a pirate hideout and many of the residents descend from these buccaneers. In 1998, Hurricane Mitch winds blew over the main island’s pine trees and wiped away many of the stilted houses. Much of the main island remains untouched by development, apart from a few houses, hotels, and an airstrip; however, tiny Bonacca Cay just offshore is perhaps the most densely populated place in Honduras, where five thousand people crowd in a maze of pastel colored houses, many of them hanging off the land on stilts. There are a few beaches on the main island, all of them quite empty and raw. Diving is good here and many boats come from Roatán on day trips.

La Mosquitia

The largest tract of virgin tropical rainforest in Central Americas remains almost entirely unexplored. Only recently have archeologists and explorers uncovered stone cities, revealing a lost civilization that remains a mystery. Covering the entire northeastern part of the country, La Mosquitia is sparsely populated, with the exception of a few small towns and isolated Pech, Tawahka, Garífuna, and Miskitos villages. The region is only loosely controlled by the government and drug traffickers have taken advantage, disrupting what was beginning to look like a blossoming ecotourism industry.

Named a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1980, the 525,000 hectares (1.3 million acres) Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve ¤ [map] is home to a diverse set of rare ecosystems including wetlands, pine savannas, and tropical forest. The only inhabitants are a few Pech and Miskito communities who live in much the same way as they have for hundreds of years. The array of flora and fauna is dazzling, with bucket list species after bucket list species: jaguars, harpy eagles, Baird’s tapirs, and many others.

Despite its natural wonders, most of the park is almost inaccessible. For much of the rainy season, travel here is impossible, while during the dry seasons, running from February to May and August to November, it requires a series of air, boat, and overland connections to get into the interior, which begins to pile on costs, especially for solo travelers. The easiest way is to fly to airstrips in the northern end of the park, such as Raista or Brus Laguna, where there’s lodging and tours can be arranged deeper into the reserve. One option is the 10- to 14-day rafting trip down the Río Plátano, which are run once or twice a year by tour operators in La Ceiba.

Laguna de Ibans

The large lagoon of Laguna de Ibans ‹ [map], separated by a narrow sandbar from the Caribbean, has been to focus of numerous tourism projects in recent years. Along its shores are several Miskito and Garífuna villages that have launched conservation initiatives. In Plapaya, the Sea Turtle Conservation Project helps protect the green, loggerhead and leatherback turtles that nest on nearby beaches from February to September. In the adjoining Miskito towns of Raista and Belén, which share an airstrip utilized by charter flights organized by tour agencies in La Ceiba, there are a few small ecolodges and a good beach. Community run tours explore the Parú, Ilbila, and Banaka creeks to spot monkeys and caimans.

Traditional house in Las Marías.

Alamy

Las Marías

Inland from Raista and Belén, Las Marías is as far upriver as you can get by motorized boat. The traditional Pech community on the Río Plátano is the base for many travelers coming to the reserve. With the help of NGOs the village has trained dozens of guides and naturalists to lead various guided hikes, like the 3-day round trip ascent to the top of Pico Dama, and canoe trips to the Walpaulban Sirpi petroglyphs. Additionally, they’ve built a few surprisingly comfortable guest rooms for those who come. All profits are split among the community. Upon arrival tourists are introduced to the sacaguia, a head guide elected for a six-month period, who coordinates all tours and rooms.