Word is quickly getting out about Nicaragua, long off the radar for all but the hardiest of travelers to Central America.

With 78 protected areas covering over 20 percent of the country, which is even more than Costa Rica, and home to seven percent of the world’s biodiversity, there is masses to explore here. While the effects of the Sandinista insurrection and several natural disasters will linger for the foreseeable future, the country’s tourism infrastructure has been on the up for years.

Looking out over the roofs of Granada and the Cathedral from the bell tower of Iglesia La Merced.

Getty Images

Along the Pacific coast, luxe resorts north of the former fishing village-turned-surf hangout San Juan del Sur can now be accessed by an airport, Costa Esmeralda, a name that follows a new marketing strategy. The faded architecture of colonial cities like Granada and León is being given a facelift, with boutique hotels and cafés moving in by the dozen. Expats, priced out of Costa Rica, are finding their way here, taking advantage of the inexpensive healthcare, not to mention the excellent rum and cigars.

Concepción volcano and Ometepe island.

iStock

Ecotourism continues to be an important enticement, with sandboarding down the slopes of Cerro Negro and the smoking crater of Masaya major geological attractions. Hikes through cloud forests, dry forests, and lowland tropical forests reveal a country swarming with wildlife. If you get tired of canopy tours, which are now a dime a dozen, there are organic farms reached only by horseback and kayaking excursions with caimans to sample.

While a potential canal may one day cut through the Caribbean coast and turn Lake Nicaragua into a major shipping route, for the time being Isla de Ometepe remains a place for volunteerism and excellent coffee. Other corners of the lake, like the artist colony on the Solentiname Archipelago and the wild islets in the north, remain much as they were decades ago. Along the Caribbean coast and farther afield on the Corn Islands, the vibe is even more relaxed, with days filled with swaying palms and snorkeling and nights vibrating to the beat of an African drum.

The post-war period

Weary of war, Nicaraguans voted out the Sandinistas in 1990 in a surprise victory for Violeta Chamorro, the widow of journalist Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, who became Nicaragua’s first female president. With the economy devastated and a series of natural disasters unfolding shortly after, such as a 1992 earthquake and 1998’s Hurricane Mitch, Nicaragua saw few major improvements in the years subsequent to Sandinista rule.

In 2006, Sandinista Daniel Ortega returned to power and was reelected in a landslide in 2011. In 2014, the congress adjusted the constitution so he would be able to run for a third term, which he won by a large margin in 2016. The general economic stability from Ortega’s social programs and business-friendly environment has been widely popular among Nicaraguans who are eager to put the past behind them. With an economy growing at double the Latin American average and a society avoiding the violence of Honduras to the north, Nicaragua appears to be in better shape than it has ever been. Still, many opponents claim that the election was a farce and that the growing autocracy, pushed by Ortega’s vice president and wife, Rosario Murillo, are keeping it from becoming truly democratic.

The potential canal

Conceived by Ortega’s administration, Nicaragua’s Grand Interoceanic Canal project was pushed through parliament in 2014 with almost no debate. Backed by HKND, a Chinese company that few know anything about, the proposed $50 billion waterway is the hope of many to finally develop a Panama-like economy and modern infrastructure in Nicaragua.

The designers say it will be the biggest earth-moving operation in the history of the world and it will clear a 286km (178-mile) -long, 30-meter (98ft) -wide channel so that the world’s largest ships can pass through the isthmus between the Pacific and the Atlantic. Additionally, developers want to add a large hotel on Isla de Ometepe and add various other ports, which will provide jobs for hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguans that sorely want them.

Despite the promises, there are serious doubts that the canal will ever get built. While ground was broken on the project in 2014, no work has been completed and there are doubts that there ever will be. Landowners have rallied against the appropriation of their property and environmentalists oppose the destruction of some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems. Opponents bring up the fact that what became the Panama Canal was once studied to be constructed in Nicaragua, but engineers determined that the location would be too prone to natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and volcanic eruptions. Additionally, Wang Jing, the Chinese telecom tycoon behind HKND, lost about 85 percent of his fortune in a stock market crash. With more questions than answers, it is anyone’s guess what might transpire.

Managua and around

Named Nicaragua’s capital in 1852, ending the rivalry between León and Granada and setting up extensive urbanization for the next 80 years, more than two million people call Managua 1 [map] home. Set on the shores of Lago Xolotlán, aka Lake Managua, parts of the city feel like the apocalypse has hit, with empty lots filled with rubble and swaths being overtaken by jungle. Much of this disorder can be traced back to December 23, 1972, when an earthquake flattened 8 sq km (3 sq miles) of the city, killing an estimated 10,000 people. Before anything could be rebuilt, revolution came and bombings knocked down buildings and sent the city’s wealthy fleeing to Miami. Only in the 21st century, as the economy has begun to stabilize, has Managua seen efforts to bring it into the modern era.

While most travelers hightail it out of the city immediately upon landing, especially with Granada being just a short drive away, those who do spend a day or two in Managua will find a major Central American city that is essentially free of tourists. The center of the city, the Zona Monumental, is where the majority of attractions and government buildings can be found. However, this neighborhood was badly damaged in the 1972 earthquake and can be dangerous outside of daylight hours.

Fact

The city of Managua straddles several fault lines that experiences major seismic activity every 50 years or so. The last major quake occurred in 1972, which destroyed large swathes of the city center and displaced two thirds of the population. A 5.6 magnitude quake and its aftershocks hit in 2014, destroying roughly 2,000 houses, but it’s only a matter of time before a bigger quake hits.

Managua’s center is the Plaza de la Revolución A [map], with its 1933 monument honoring the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío. The Catedral Vieja, or at least what is left of it, is less than a block to the east. While the church, which dates from 1929, is too fragile to enter, visitors can still glimpse at the frescoes and statues inside. To the south, attached to the National Library, is the Palacio Nacional de la Cultura B [map] (tel. 2222 2905; as Mon–Fri 8am–5pm, Sat 9am–4pm, Sun 10am–5pm), where Sandinista rebels staged a hostage siege in 1978, resulting in the release of political prisoners. Today the building is home to the National Museum, with a collection of Pre-Columbian ceramics and artifacts, as well as various pieces and displays from the revolution.

Built in 1969, the Teatro Nacional Rubén Darío C [map] (www.tnrubendario.gob.ni), to the north of the plaza near the malecón (pier), was one of the few buildings to survive the 1972 earthquake and continues to be an integral part of Managua culture with regular dance exhibitions and concerts.

The sprawling lakefront complex in the old port area, Puerto Salvador Allende D [map], stretches for several kilometers and is lined with restaurants, playgrounds and beach access. Opened in 2008, it has quickly become the preeminent tourist attraction in Managua. There is live music and roving performers on the weekends, and boat trips to the Island of Love.

Discovered by miners in 1874, the Huellas de Acahualinca E [map] are the fossilized tracks on the shore of Lake Xolotián of a small group of people, as well as various animals and birds that date back an estimated 6,000 years. It’s believed that volcanic ash covered the footprints, perfectly preserving them. There is a small site museum (Mon–Fri), with an exhibition of Pre-Columbian ceramics. It’s in a rough neighborhood near the Mercado Oriental, so it’s best to take a taxi in and out.

A national historic park southeast of the center on the edge of Volcán Tiscapa, Loma de Tiscapa F [map], looks out over a small crater lake and is home to Managua’s most recognizable landmark, a statue of revolutionary hero Augusto Sandino. The site was once the home of Somoza’s presidential palace; it’s now home to a collection of Sandinista monuments, such as a tank donated by Mussolini. There are stunning views of the lake and center, as well as a canopy tour (tel: 8872 2555).

Managua, Nicaragua’s capital.

iStock

Eat

For years, on Mon–Fri from 6pm until the food runs out, Doña Pilar has been setting up her sidewalk fritanga on 10 Ave SE near the Tica bus terminal. The no-frills grill is one of Managua’s most iconic eating spots, known for its grilled chicken served with heaping piles of gallo pinto and pickled cabbage at bare bones prices.

Outside of Managua

The 184-hectare natural preserve of Chocoyero-El Brujo, 23km (14 miles) south of Managua, protects one of Managua’s primary water sources. Dissected by a network of hiking trails, the park contains two waterfalls, El Brujo and Chocoyo, both around 25 meters (82ft) in length. At around 3pm each day, flocks of chocoyos, a variety of the Pacific green parakeet, can be seen flying around the cliffs of the canyon near the Chocoyo falls. Also within the lush green park are toucans, two types of monkeys, and other small mammals.

In the town of Tipitapa, about 22km (16 miles) east of Managua along the shore of the lake, you will find the El Trapiche hot springs, a basic thermal pool overlooking the Tipitapa River.

Northern Nicaragua

Despite being well removed from the tourist trail, the mountainous northern half of Nicaragua has some of the country’s most interesting attractions. Dotted with patches of picturesque farmland and cloud forest dripping with waterfalls in the east, and volcanoes and hot lowlands toward the Pacific, waves of colonists, from pirates to the Spanish to revolutionaries, have all made their mark here.

For much of the past century the region has been plagued with wars and natural disasters. The turbulence began in the early days of Spanish settlement, when a volcanic eruption destroyed the original setting for León; emerged in the conflicts of the 1930s, when General Sandino battled American marines; continued with the Sandinista struggle in the 1970s; the Contras a decade later; and culminated with Hurricane Mitch in 1998, which left countless towns devastated.

Today the north is one of the most industrious parts of the country as the setting for coffee farms around Matagalpa and the tobacco plantations near Estelí. There’s also cycling through the pine-filled valley that surrounds the colonial town of Ocotal, and hiking through the gorges outside of Jinotega. More of a DIY Nicaragua than Granada or the Pacific coast, the north is full of authentic rural character.

Matagalpa.

Getty Images

Matagalpa

Surrounded by green hills, the valley town of Matagalpa 2 [map] is an important economic engine for Nicaragua, being the heartland of the country’s coffee industry. The country’s fourth largest city, nicknamed the ‘Pearl of the North,’ was originally an indigenous settlement of the Matagalpa culture, fierce warriors known for their stone statues that disappeared in 1875. The Spanish arrived here in 1528, but it wasn’t until gold was discovered that Matagalpa really began to grow, attracting mestizo settlers and many German, American, and British immigrants, including Ludwig Elster and his wife Katharina Braun, who planted the first coffee plants.

While many visitors spend much of their time outside of the city, there are several interesting pieces of colonial architecture in town, like the neoclassical Iglesia San Pedro fronting Parque Morazán. The church dates to 1874 and features a wood altar and whitewashed exterior. To the east of Parque Dario is the humble adobe birthplace of Carlos Fonseca Amador, who founded the FSLN and is widely regarded as Matagalpa’s most famous son. Now a museum, the Casa Museo Comandante Carlos Fonseca (Mon–Fri), the house displays various pieces of revolutionary history.

A unicyclist turned revolutionary

A California-born engineering graduate named Benjamin Ernest Linder, inspired by the Sandinista Revolution, moved to Nicaragua in 1983 to help the country’s poor. After several years in Managua he moved to the northern highland town of El Cuá, in the middle of a war zone where the Sandinistas were fighting the US funded Contras. Linder helped build a hydroelectric plant, bringing electricity to the village of San José de Bocay, and launched vaccination campaigns against measles. However, Linder will always be remember for his talents as a clown, who amidst the horrors of war, entertained the village children as he juggled and rode his unicycle.

In 1987, Linder and two Nicaraguan friends were ambushed by Contras while walking through the forest, an incident that raised international headlines, leading to questions about the US role in Nicaragua. Congress withdrew support for the war a year later. Linder is fondly remembered throughout the north as the juggling ambassador, with murals plastered around the region. President Ortega posthumously awarded him the country’s highest civilian honor and served as a pallbearer at his funeral. Numerous books and songs have been dedicated to Linder, including Sting’s Fragile on the 1987 album, ...Nothing Like the Sun.

Outside of Matagalpa

Finca Esperanza Verde (http://fincaesperanzaverde.com) is an ecolodge on a coffee farm with various cloud forest trails. Set at 1,200 meters (4,000ft) above sea level near the town of Yúcul, east of Matagalpa, it has stunning views of the green hills. Open to the public during the day, it’s a popular day trip from Matagalpa.

Founded in 1891 by German immigrants, the Selva Negra Ecolodge (www.selvanegra.com) 11km (7 miles) outside of Matagalpa was a coffee estate that became a tourist resort in 1976. Arguably the most famous hotel in Nicaragua, the cool highland resort has long been a favorite escape of the country’s elite who come to hike, wander through the organic farm, or look for birds such as tanagers or manakins in the surrounding forest.

Jinotega

Beyond Selva Negra, the road continues north to Jinotega 3 [map], which is one of the most scenic drives in Nicaragua. The mountain highway hovers above 1,500m (5,000ft) for much of the way, an ideal setting for coffee plantations and lush, green farmland. Set in a misty valley ringed by granite ridges and thick cloud forest, Jinotega’s quaint cobblestone streets are perpetually covered with rain. An easy yet sweaty hike for a birds-eye view of the city is to Cerro La Cruz, marked by a cross placed here in 1703 by Franciscan Fray Margíl de Jesús. A pilgrimage site, the mirador hosts the Fiestas de la Cruz from April 30 to May 16 each year, the city’s biggest party.

To the northeast, en route to Estelí, is San Rafael del Norte, one of the highest towns in Nicaragua. Dating to the late mid-17th-century, the rural village has opportunities to hike deeper into the mountains, as well as to visit coffee fincas.

East of Jinotega is the Reserva Natural Cerro Datanlí-El Diablo, a 10,000-hectare (24,710 acre) cloud forest reserve with a rich array of flora and fauna. A network of trails enters the reserve from the communities surrounding it. The solar-powered La Bastilla Ecolodge (http://bastillaecolodge.com), with all profits invested back into a jointly-run agricultural and tourism school, offers guided hikes and horseback riding to waterfalls and coffee fincas within the reserve.

Estelí

Near the border with Honduras, just off the Pan-American highway, Estelí 4 [map] is a university town that gave rise to the Sandinistas. Set in a broad valley surrounded by forested hills, the highland city is Nicaragua’s third largest. Beyond the shady main plaza and adjacent whitewashed cathedral, which dates to 1823, are multiple tributes to the revolution, such as a series of murals and the Galería de Héroes y Mártires (Tue–Fri 9.30am–4pm), with photos and various artifacts from the battles against the Somoza government in the late 1970s, which destroyed much of the city and killed an estimated 15,000 people. Bullet holes can still be seen in many of the buildings around Estelí. Rural Estelí comes alive on Saturdays, when farmers from the surrounding countryside come to the sprawling produce market to sell their harvests. A modern commercial complex with a hotel, mall, and movie theaters is a symbol of the town’s progress.

After the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Cuban cigar makers flocked to Estelí to take advantage of the ideal tobacco growing conditions in the surrounding countryside. Today, some of the best cigars in the world come from the city and it remains one of the primary local industries. While most cigar factories do not offer tours, some do, and these can be set up through any hotel or tour agency in town. The tours reveal how the leaves are dried and the tobacco rolled, though some are more elaborate with multi-day itineraries that include extensive sampling and visits to farms, such as at Drew Estate (www.cigarsafari.com).

Roughly 30km (19 miles) northeast of Estelí is the Miraflor Cloudforest Reserve, notable for the tourist-friendly organic farming community that adjoins it. The reserve centers on a mountain lake ringed by primary forest that is transected by hiking trails to several waterfalls.

Working at a cigar factory in Estelí.

John Bustos/REX/Shutterstock

Ocotal

The Spanish began settling in what is the scenic Nueva Segovia region in 1534, though pirates sailing up the River Coco from the Caribbean in search of gold repeatedly attacked. The settlers moved to what is now Ocotal 5 [map] in 1654, quickly developing an important source of timber for the growing nation. In 1927, Augusto Sandino and his army seized the city in their first major blow to government forces, which resulted in a devastating air raid by the US marines. Today, the city of 30,000 is home to a lovely central plaza filled with tropical foliage, pine trees, and flowers, and sided by a neoclassical church.

The surrounding countryside, chock-full of cattle ranches and coffee fincas, makes for fine cycling and several tour agencies and hotels in town will rent bikes.

Southwest of Ocotal on the Pan-American Highway, not far from the Honduran border, is the Somoto Canyon, a rugged gorge with unusual rock formations.

Tip

Every Saturday on the north side of León’s main plaza, Parque Juan José Quezada, a community fiesta called Tertulia Leonesa is held to showcase the best of the city’s cultural traditions. Micro-artisans sell traditional handicrafts and foods, while folkloric musicians and dancers perform for onlookers.

León and around

Closer to the Pacific coast, near the Honduran border, León 6 [map] is the country’s second largest city with a population of 200,000. Founded in 1524 by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, it was abandoned in 1610 after earthquakes turned much of it to rubble. The settlement was then moved about 30km (20 miles) east to where the present-day city now stands. Long the liberal and intellectual capital of the country, León was the political capital too from colonial times until the mid-1800s, when this title moved back and forth from more conservative Granada before finally landing in Managua. During the revolution the city was a stronghold of the Sandinistas, leading to a brutal backlash from the Somoza regime, which burned down the city’s central market.

León’s cathedral is the largest in the region.

iStock

The swelteringly hot lowland city has maintained its colonial core, with more than a dozen 18th-century churches, many of which are connected by underground tunnels once used to escape pirate attacks and now part of the sewer system. The colonial baroque Basilica Catedral de la Asuncion (tel: 2311 4820; Mon–Sat 8am–noon, 2–4pm; free) was built between 1747 and 1814 and is the largest cathedral in Central America. Having endured earthquakes and bombings, it has become a symbol of the city itself: proud and resilient. Within the crypts are the tombs of some of the most important figures in Nicaraguan history, such as the poets Rubén Darío and Salomón de la Selva, the father of independence Miguel Larreynaga, and composer José de la Cruz Mena.

Founded in 1639 by Friar Pedro de Zúñiga, the church and convent of San Francisco (hours vary; free), two blocks west of the plaza, is one of the oldest in the country. With its plateresque altars, courtyard lined with lemon trees, and porticoes covered in red bougainvillea, it’s one of the most attractive examples of Leónese colonial architecture. Dating to 1786, the Iglesia de la Recolección (hours vary; free), three blocks north of the plaza, features a Mexican Baroque facade and altarpieces. Opposite the cathedral is the Museo de la Revolucion (daily), dedicated to the Nicaraguan revolutionaries who stood up to the Somozas, while the Museo Rubén Darío (daily) is where the country’s favorite poet spent his first 14 years and is filled with various relics from his life. A block away, the Centro de Arte Fundación Ortíz-Gurdián (www.fundacionortizgurdian.org), set in two colonial houses, holds Nicaragua’s best art collection, with contemporary works of Nicaraguan painters and even works from Rembrandt and Picasso.

The skyline of Granada at sunset.

iStock

Outside of León

The ruins of the original León, a Unesco World Heritage Site known as León Viejo 7 [map] (daily 8am–5pm), were laid buried in ash from the 1610 eruption of the Momotombo Volcano. The ruins were lost for 300 years until the late 1960s; excavations have revealed brick walls and the general layout of the city, as well as the cathedral and plaza, with the headless remains of founder Francisco Hernández de Córdoba beneath it. The site can be visited on a day-long guided tour through any agency in León, such as Vapues (www.vapues.com), and are usually combined with a hike to the top of the Cerro Negro Volcano, with options for sandboarding down the black volcanic slopes.

On the coast, the Reserva Natural Isla Juan Venado, 18km (11 miles) long, is an uninhabited barrier island with wide, desolate beaches and mangrove forests in the interior reaches. Kayak trips through the canals can be arranged in León, as can turtle tours from July to December, when Olive Ridleys, leatherbacks, and other turtles arrive in their thousands to lay their eggs in El Vivero, close to Las Peñitas. Just north of Las Peñitas is Poneloya, the far north’s most popular beach destination. A fishing village with seafood restaurants fronting the beach, there are several small hotels here and there is regular bus service from the Mercadito Subtiaba in León.

Granada and the Masaya Region

The short distance between Managua and Lake Nicaragua is one of the most visited in Nicaragua. For many travelers, the cobblestone streets and colonial townhouses-turned-boutique hotels in Granada serve as a base from which they explore the rest of the country. Easy day trips from the city allow for hikes on the forested slopes of the Mombacho Volcano or for soaks in the hot springs below it. Options for extended stays in the wilderness can be found in the ecolodges along the turquoise waters of the Laguna de Apoyo or on the islands in the tranquil Isletas de Granada on the lake.

Granada and around

Founded in 1524 by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, Granada 8 [map], near the base of the Mombacho Volcano, was the first official European city in mainland America. La Gran Sultana, nicknamed for its Moorish and Andalusian architecture, was an important port city on Lake Nicaragua throughout the colonial period, making it a target for English, French and Dutch pirate attacks. In 1856 American adventurer William Walker, after taking up residence in the city, set it on fire while surrounded by opposing forces, planting a sign declaring ‘Here was Granada.’ Despite the tumultuous history, Granada has some of the best preserved colonial architecture in all of Central America.

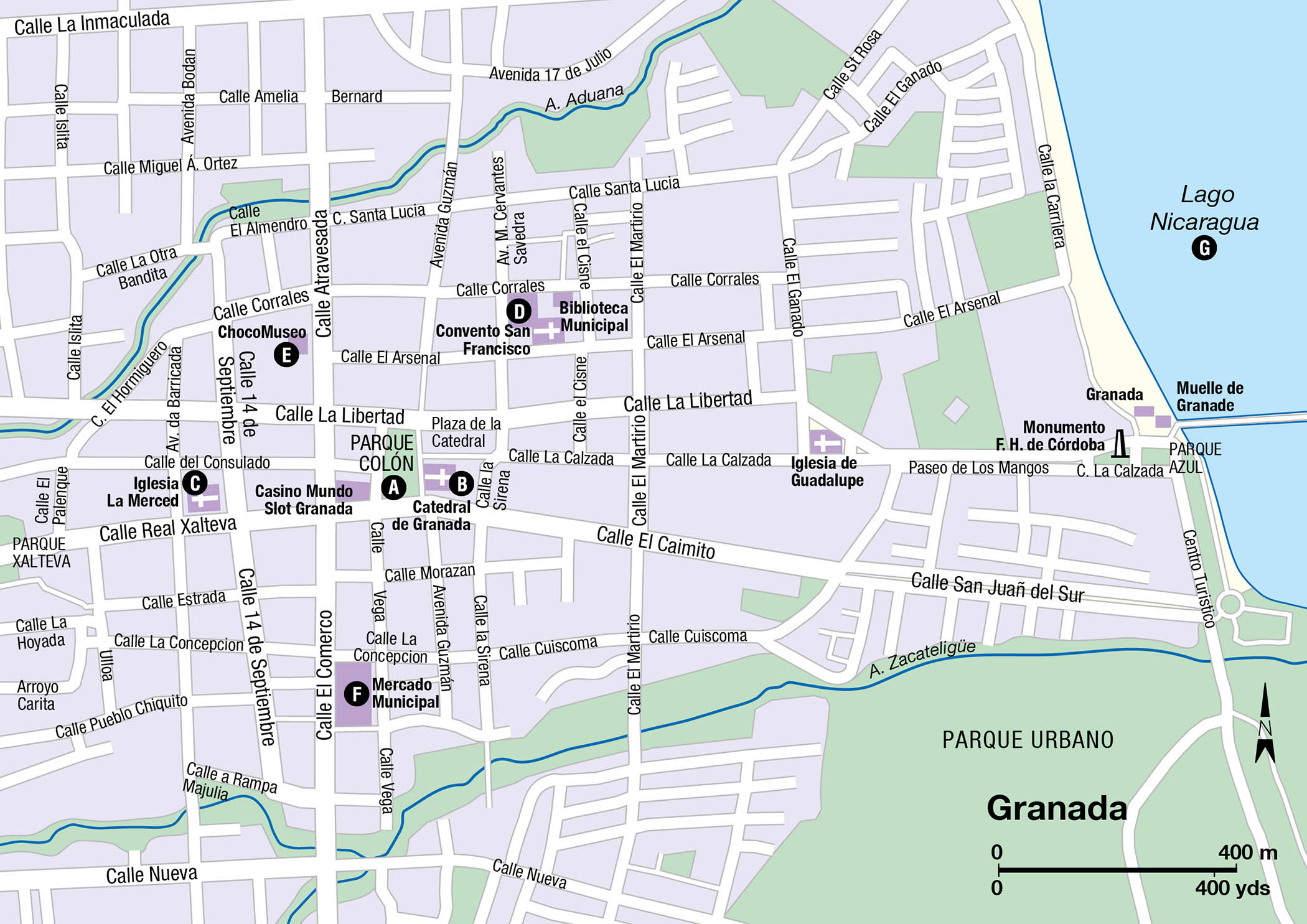

Orientation

The center of Granada’s historic core is at Parque Colón A [map], a vibrant central square where parrots squawk in the tall palms and food stands sell vigorón, a traditional snack of pork and cabbage wrapped in banana leaf. Surrounding the plaza are many colonial buildings, like the ritzy Hotel Plaza Colón (http://hotelplazacolon.com) and the Catedral de Granada B [map] (hours vary; free), which was originally built in 1583, though it has been destroyed and rebuilt multiple times. Also on the plaza is the Casa de los Leones, an elegant house that dates to 1720, now a cultural center.

At Real Xalteva and 14 de Septiembre, the Baroque Iglesia La Merced C [map] (daily 11am–6pm) dates to 1534 and has undergone several rebuilds and renovations, although it has maintained its beauty. Inside, a spiral staircase leads up to a bell tower with some of the best views of the city. The pale blue Convento San Francisco D [map] (tel: 2552 5535; Mon–Fri 8am–4pm, Sat–Sun 9am–4pm), one of Nicaragua’s oldest buildings, is a block farther east of the cathedral. Having been famously destroyed by both the pirate Henry Morgan in 1679 and then by William Walker in 1856, the galleries now contain a museum (daily) with a collection of pre-Columbian basalt statues from Zapatera Island.

On Calle Atravesada northwest of the plaza is the Choco Museo E [map] (www.chocomuseo.com; daily 7am–6.30pm), a chocolate store with chocolate-making workshops and farm tours. East of the plaza, along the pedestrian-only Calle La Calzada, is the primary concentration of stores, restaurants, and nightspots in the city. Several hip boutique hotels like the Hotel Dario (www.hoteldario.com) and Tribal (www.tribal-hotel.com) are found here as well. To the south is the neoclassical Mercado Municipal F [map], constructed in 1892, which spills out into the surrounding streets, while farther west is the municipal cemetery, with stone tombs that date to the late 19th-century and contain the remains of six Nicaraguan presidents. There’s also the neoclassical Capilla de Animas, modeled after a French chapel.

Market day in Granada.

iStock

On the eastern end of Calle La Calzada is the shore of Lake Nicaragua G [map] where there are a few bars and a waterfront boardwalk that gets crowded on weekends.

Outside of Granada

Twenty-minutes west of Granada is the Laguna de Apoyo 9 [map], Nicaragua’s largest volcanic lagoon. More than 200 meters (656 ft) deep and 6km (4 miles) in diameter, the caldera is ringed with lush forests where toucans and white-face monkeys can easily be spotted on a short hike. A few restaurants and ecolodges, some of which rent kayaks, can be found on a strip along the northwestern shore of Apoyo, though the majority of visitors come on a day trip from Granada.

The archipelago of 354 jungle clad islands called Las Isletas ) [map] are easily reached from Granada’s waterfront. While many of the islands have been purchased by wealthy residents of Managua, who have built mansions on them, others – often just the length of a fishing line away – are quite humble, with rustic yet charming wooden shacks. From the southern end of the Complejo Turístico Cocibolca near Granada, boat tours explore the islands, stopping at the small Spanish fort of San Pablo. Another way of experiencing Las Isletas is to stay at the eco-friendly Jicaro Island Lodge (www.jicarolodge.com), the premier hotel in Las Isletas and built using local materials. The lodge helps fund an organic farm on one of the islands and supports several schools.

Managed by the Fundación Cocibolca – which has built a network of trails, a butterfly garden and organic coffee farm – the Mombacho Volcano Natural Reserve (www.mombacho.org) south of Granada along the lake is a popular day trip from Granada. Home to three species of monkeys and nearly two hundred species of birds, the lush jungle here has been well preserved. Treks go up to the lip of the crater and around, though the steep, sweaty trails are not for the unfit.

Masaya

Nicaragua’s capital of folklore, Masaya ! [map], is just 9km (5.5 miles) from Granada. Surrounded by hissing volcanoes and tiny rural villages known for their handicrafts, Masaya is where to come to buy souvenirs. While the city of 100,000 was badly damaged in the 2000 earthquake, the markets, craft workshops, and old churches here remain in good condition. Most head straight for the Mercado de Artesanías de Masaya, an artisan market selling hammocks, pottery, woodcarvings, and leather good, among other things.

It’s also possible to go direct to the source of the handicrafts, which are mostly created in a string of mountain villages called the Pueblos Blancos. Scattered within 15 km (9 miles) of the city are Nindiri, Niquinohomo, Masatepe, Catarina, Diria, and Diriomo, each with their own specialty.

The Masaya volcano is highly active.

iStock

Volcán Masaya National Park

Nicaragua’s first and largest national park, the 54 sq km (34 sq miles) Parque Nacional Volcán Masaya @ [map] is the home of five craters and two calderas. The extremely active Masaya caldera, known as the ‘Gates of Hell’ to the Spanish, exploded as recently as 2001, allowing a new vent to form; ash and steam regularly shoot out into the sky above. While the situation is always changing depending on the level of activity, and the park is often closed to visitors, the standard tour allows for about 30 minutes at the viewpoint overlooking the crater, where steam and bubbling lava can be seen. The road runs nearly to the top of the crater, with the visitor center halfway up, while a network of 20km (12 miles) of hiking trails branches out from it.

Lake Nicaragua and around

Lake Nicaragua, also called Lake Cocibolca, is nearly the same size of South America’s Lake Titicaca, which is why the Spanish nicknamed it the ‘Mar Dulce,’ or Sweet Sea. There are plans to make the lake the centerpiece of a canal project that would rival the one in Panama, likely causing serious environmental degradation, though it might never become a reality. For now, the lake is an ecotourism hotspot, with the island of Ometepe – made of two volcanoes and the narrow strip of land between them – as the focal point. Farther afield is the Solentiname archipelago, an artist colony, and the Rio Coco, which runs parallel to the Costa Rican border and gives access to the Caribbean coast.

The sharks of Lake Nicaragua

The relatively shallow waters of Lake Nicaragua are the last place anyone would expect to find a shark. Their appearance surprised scientists who believed they were a unique freshwater species – until 1976, when the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Thomas B. Thorson tagged some them, revealing that highly adaptable Caribbean bull sharks (Charcharinus leucus) were able to swim the 193km (120 miles) span of the San Juan River from the Atlantic coast. The sharks have adapted to the freshwater of the lake and can grow up to 3 meters (11ft) in length. A Japanese shark-fin factory was established near Granada during the Somoza regime, and even though it closed in 1970, the population of bull sharks has yet to recover. With increasing habitat destruction and a potential canal cutting through the middle of the lake, its highly likely that the sharks could completely disappear from here.

Isla de Ometepe rises from Lake Nicaragua

Getty Images

Isla de Ometepe

The world’s largest volcanic island within a freshwater lake, Ometepe £ [map] is one of Nicaragua’s primary attractions, even though it’s quite rugged and lacks much infrastructure. Seeing the island’s twin volcanic peaks from the lake – the perfectly conical Concepción and forest covered Madera, connected by the Istián isthmus – is one of the most majestic sights in the country or anywhere else, for that matter. Primarily used for agricultural purposes, nearly anything will grow in Ometepe’s rich volcanic soil, including coffee, bananas, and avocados. Pre-Columbian petroglyphs and rock carvings are found across the island, though there is likely much more to be discovered beneath the thick jungle. Most visitors arrive via the hour-long ferry ride from San Jorge near Rivas, though the airstrip occasionally has flights from Managua. There have long been rumors of a luxury resort being built, but many simply prefer to leave Ometepe as it is.

Moyogalpa and around

With a regular ferry service from San Jorge, Moyogalpa $ [map] is the gateway to Ometepe for most travelers. From the terminal, a road lined with stores, tour agencies, and seafood restaurants runs uphill several blocks to the main ring road that circles the Concepción volcano and the northern half of the island. The largest town on the island and most active, it is rather charming, with a small grid of whitewashed houses with tile roofs and Concepción looming above from every angle.

Moyogalpa makes a good base for a hike up the 1,610 meter (5,282ft) high Concepción, with the trailhead 4km (2 miles) north of town at La Concepción. The ascent takes about three hours up and allows for plenty of time to spot monkeys and birds.

Southeast of Moyogalpa is the Reserva Charco Verde, a green lagoon surrounded by jungle and a windy, black sand beach facing the lake. A few simple hotels, a restaurant, and a butterfly farm are just west of the lake.

On the opposite side of the volcano from Moyogalpa is Altagracia, close to where the ferries from Granada dock. The second largest town on Ometepe, it has a small museum with Pre-Colombian ceramics discovered on the island, though it opens at will.

Around Volcán Madera

The southern half of Ometepe, on the isthmus and surrounding the Madera Volcano, is less developed and has more variety in terms of ecotourism. Playas Santo Domingo and Santa Cruz on the eastern side of the isthmus are the best beaches on the island, with black sand and the green jungle creeping up right to the shore. A few rustic hotels and restaurants dot the shoreline.

The road from Santa Cruz to Balgüe, as well as south to San Ramon, has improved dramatically in recent years, opening up the tropical and cloud forests and coffee farms on the northern slopes of Madera to tourists. Several organic and permaculture farms in the area have tourism and/or volunteering projects, including Zopilote (http://ometepezopilote.net), Totoco (www.totoco.com.ni), Finca Magdalena (www.fincamagdalena.com), and Café Campestre (www.campestreometepe.com).

Kayaking Lake Nicaragua at sunset.

Getty Images

San Carlos and around

On the southern eastern shore of Lake Nicaragua, where it meets the San Juan River, San Carlos % [map] is a bustling port town that isn’t much to look at. However, the strategic setting was recognized centuries ago as a place to control a waterway that nearly connects two oceans. After being founded in 1526, the town developed quickly, though pirate attacks and feisty natives upset about rubber tappers encroaching their land kept San Carlos from becoming too powerful.

Most travelers pass through here on their way to the Solentiname Islands, using their time while waiting for boats to hang out at the string of bars and restaurants located in stilted wooden houses over the water. San Carlos has a small, yet impressive, Spanish built fort that dates from 1724 and offers stellar views of the river from a hill above town, as well as a lively waterfront promenade.

Agencies in town can arrange tours east along the San Juan River, where there are several unique hotels like Sabalos Lodge (www.sabaloslodge.com), which has a private reserve and handful of stilted cabins, plus options for sport fishing. A Spanish-built fortress can be seen at El Castillo (daily), which is much stronger than the one in San Carlos. It dates from 1673 and was commissioned after Granada was repeatedly sacked by pirates. A 20-minute drive farther east takes you to the 2,606-sq-km (1,006 sq mile) Reserva Biológica Indio-Maíz, the second largest tract of rainforest in Nicaragua. While most of the reserve is off limits to all but scientists, some portions are accessible to tourists, including from the all-inclusive Rio Indio Ecolodge (http://therioindiolodge.com), which has a resort atmosphere.

Los Guatuzos Wildlife Reserve

On the south side of the lake on the Costa Rican border, where it connects with the Caño Negro Wildlife Refuge on the other side, the Los Guatuzos Wildlife Reserve is one of the most pristine ecosystems in Nicaragua, with more than 400 species of birds and a healthy population of jaguars. Descendants of the Zapote and Guatuzo people live within a few small fishing communities hidden in the mangroves and can provide rustic rooms and meals, usually set up through the CANTUR office in San Carlos, which can arrange boat transportation into the preserve.

Archipiélago de Solentiname

In the quietest corner of Lake Nicaragua, the 30-plus small tropical islands that make up the Archipiélago de Solentiname ^ [map] have been the unlikely center of the internationally renowned primitive art movement. In the 1960s, the poet and priest Ernesto Cardenal helped inspire the islanders to paint the flora and fauna around them. Other artists came, as did television crews to capture the phenomenon, and today many of the roughly 1,000 residents here make a living painting and carving sculptures of local fauna out of balsawood. Most tourist amenities, which are few, are concentrated in Mancarrón, the largest island and where Cardenal based his colorful parish in the whitewashed Iglesia Nuestra Señora de Solentiname. There’s a small archeological museum and a couple of small guesthouses here as well.

The Solentiname islands are located towards the southern end of Lake Nicaragua.

Getty Images

Traversing a continent

During the California gold rush, thousands of would-be prospectors from the east coast of the United States came by ship to Nicaragua, where they were able to cross the country via the San Juan River to Lake Nicaragua and then overland to the Pacific, where they could catch a ship up to the north. In the years shortly after this, one famous American traveler who crossed Nicaragua en route to New York from California was the writer Mark Twain, who published a series of dispatches about his adventure in San Francisco’s newspaper, the Alta California. Twain’s 1866 journey has since been immortalized in his posthumously published 1940 book Travels With Mr. Brown.

The Pacific coast

Much of the attention Nicaragua has received in recent years has been focussed on the south of the country, particularly the narrow stretch of land between the Pacific coast and Lake Nicaragua. Many travelers coming up from Costa Rica looking for the next great beach destination found it long ago in San Juan del Sur and the collection of surfing and fishing villages, isolated coves, and bays up and down the coast. With improving highways and the Costa Esmeralda airport – offering regular flights to Managua – much more development is expected in the coming years. Closer to the lake, the old colonial town of Rivas, long faded into memory, is taking on a new lease on life as the transportation hub of the region.

San Juan del Sur’s beachfront.

Getty Images

Rivas and around

Located on the Pan-American highway along the shore of Lake Nicaragua is Rivas & [map], 110km (68 miles) south of Managua. While many passing through Rivas only see a highway lined with modern buildings and gas stations, its charming Parque Central and 18th-century church is surrounded by a Spanish-designed grid of streets that are still full of original architecture. It’s where tyrant William Walker failed to penetrate and also the birthplace of former president, Violeta Chamorro, who is credited with reuniting the war-torn country in the 1990s.

East of Rivas, opposite the highway is San Jorge, with a long windswept beach and a bustling port offering with regular ferry services to Ometepe. There are a few traditional restaurants and B&Bs within walking distance of the port.

San Juan del Sur

A little more than a couple of decades ago, word started to get out about a sleepy fishing village with great surf breaks called San Juan del Sur * [map]. The surfers came, then the backpackers, and then the wealthy Nicaraguans and North American retirees, looking to take advantage of the inexpensive beachfront real estate, snapping up whatever they could. Prices have since ballooned, both to the pleasure and dismay of locals. Some found themselves getting rich, while others were priced out of their once-tranquil neighborhoods. Local anger reached a boiling point in 2006 when an American realtor was convicted of murdering his Nicaraguan ex-girlfriend and sentenced to 30-years in prison. The verdict was overturned a year later after it was proved to be a miscarriage of justice, but an outraged public had wanted to place blame on the gringos that had been disrupting their community. Things have since calmed down and the development on the beaches surrounding San Juan del Sur has spread up and down the coast.

San Juan del Sur’s main attraction, the beach, encircles a crescent shaped bay where the San Juan River empties into the Pacific Ocean. Aside from a few beachside restaurants, most amenities are set back from the beach’s southeastern corner, in a seemingly thrown-together grid packed with surf stores, a microbrewery, an artisanal donut shop, taquerias, and dozens of small hostels and hotels. The more upscale resorts, like Pelican Eyes (www.pelicaneyesresort.com), with three pools and a day spa, are set back from the bay in the hills above town.

On the southern end of the bay is a lookout point where humpback and occasionally blue whales can be seen from November to April. On the highest hill on the north side of the bay, a 25 meter (82ft) statue of Jesus, Cristo de la Misericordia, can be reached on a one-hour hike from the beach, giving spectacular views of the bay.

The view from the Cristo de la Misericordia of San Juan del Sur bay.

Shutterstock

Beaches outside of San Juan del Sur

While San Juan del Sur is the hub of activity along the Pacific, its beach is only so-so. Small coves hidden within the dry hills to the north and south of town have more attractive sand, better waves, and are seeing a speedy influx of new resort communities. Reached by water taxi or along a bumpy, partially paved road from Highway 72 north of San Juan del Sur, Playa Marsella is one of the most accessible good beaches from the town. The road comes right up to the beach and there are a few simple restaurants and guesthouses within a short walk of the waterfront.

A couple of kilometers north is Playa Madera, with a long white sand beach that is popular with both surfers and sunbathers. Clustered in the jungle-clad hills above the beach are a mix of budget surf hostels and upscale hotels like Hulakai (www.hulakaihotel.com) and the Buena Vista Surf Club (http://buenavistasurfclub.com). At Playa Ocotal, where the beach road ends, is the luxe Morgan’s Rock Hacienda and Ecolodge (www.morgansrock.com), set on a 4,000-acre private reserve.

The beaches south of San Juan del Sur are less developed, though no less spectacular. The first good beach is Playa Remanso, which is home to a gated vacation home community and a few palapa (open-sided structure with thatched roof) restaurants on the sand. Playa Hermosa, 20-minutes south, is where the US competitive reality television show Survivor once filmed a season. It has a long white beach popular with surfers and there’s little development, other than the solar powered Playa Hermosa Ecolodge (www.playahermosabeachhotel.com). The Refugio de Vida Silvestre La Flor, 20km (12 miles) south of San Juan del Sur, is an important nesting area for Olive Ridleys, as well as hawksbill, leatherback, and green turtles. They arrive en masse from July to January and groups come nightly from San Juan del Sur to protect the eggs.

How the other half live; the penthouse suite at the Mukul hotel.

Leonardo

Tola and beaches

Looking for a more authentic scene than the cookie cutter communities being built around San Juan del Sur, developers started carving out the even more dramatic, 30km (18 miles) stretch of coastline west of the tiny town of Tola ( [map]. The town, located between Rivas and the coast, is little more than a service hub with a shady central plaza and a smattering of stores. The Costa Esmeralda airport, which opened close to the beach in 2016, offers direct flights from Managua with the Nicaraguan La Costeña airlines, as well as from Liberia in Costa Rica with Sansa Airlines.

The southernmost of Tola’s beaches is the private Playa Manzanillo, where Guacalito de la Isla, a 1670-acre (675-hectare) luxury resort community, is located. Owned by the billionaire Pellas family, who also own Flor de Caña rum and Toña beer, the Mukul hotel (www.mukulresort.com) offer Nicaragua’s most luxurious accommodations, with a David McLay Kidd signature oceanfront 18-hole golf course, full service spa, and rooms with private plunge pools.

Next is Playa Redonda, home of the luxe Aqua Wellness Resort (http://aquanicaragua.com). More accessible to the public is Playa Gigante, a popular beach with weekenders from Rivas, only an hour away. Backed by thick jungle, the crescent-shaped beach has a few seafood restaurants and small hotels. Fishing boats bob in the bay, while world-class breaks attract a steady stream of surfers.

North of the long, mostly undeveloped beaches of Playa Amarilla and Playa Colorado is Playa Santana, which is really five beaches. The 1,100-hecatre (2,700-acre) Rancho Santana (https://ranchosantana.com) is an intentionally rugged, private complex with multiple residential communities that share a beach club, organic farm, and surf center. A clubhouse and hotel complex on the northern end of the property is the hub of activity.

The road is still being paved to Playa Popoyo, which is one of the premier surfing destinations in Nicaragua. Farther north is the Refugio de Vida Silvestre Río Escalante-Chacocente, a remote wildlife refuge where thousands of Olive Ridley turtles, as well as four other types, come to nest from July to December.

Fact

The name ‘Nicaragua’ was given to the country by the Spanish, who combined the name of a chief of an indigenous tribe called ‘Nicarao’ in the náhuatl language and the Spanish word ‘agua,’ or water, after the lake.

Dancing in Bluefields during Palo de Mayo.

Photoshot

The Caribbean coast

The Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, formerly known as the Mosquito Coast, takes on a character that is more like the Bay Islands and coasts of Honduras and Belize than the rest of Nicaragua. Fierce Miskito resistance, plus British support of Mosquito kings from 1655 until 1860 – claiming the region as a protectorate in exchange for access to isolated bays and coves – prevented the Spanish from conquering the region. It wasn’t until 1894 that Nicaraguan president Zelaya marched into Bluefields to lay claim to the coast, but even today, amidst calls for autonomy and after so many years apart, it feels like a land joined in name only with the rest of Nicaragua.

Many in the region speak creole and still have English surnames, the same ones as the pirates that once frequented the area, such as Morgan and Dampier. Along the lagoons and muddy rivers surrounded by thick tropical forests are communities of indigenous Miskito, Mayangna, Rama, and Garífuna, who maintain their own way of living in the wild terrain. There is real, unabashed culture here that doesn’t know air-conditioned malls or cable TV. The entertainment in gritty towns like Bluefields involves colorful parades fueled by sugarcane liquor and calypso.

Managua to the Caribbean

From Managua, Highway 7 runs parallel in spots to the Mico River, passing through Juigalpa , [map], where there’s a small archeological museum, the Museo Arqueológico Gregorio Aguilar Barea (tel: 2512 0784; Tue–Sat 8am–noon, 1–5pm, Sun 9am–noon, 1–3pm), which is home to the most important of Pre-Columbian stone stelae in Nicaragua. More than 100 of the basalt statues were carved between 800 and 1500 AD. Finally, the road comes to El Rama, a town of 50,000 that’s six hours from Managua. This isolated port on the Escondida River is as far east as you can go by road. From here, tiny prop-planes and riverboats run to the coast at Bluefields.

Bluefields

Named after a Dutch pirate named Blewfeldt, the port town of Bluefields ⁄ [map] is a mish-mash of cultures, from West Indian and Miskito to mestizo. Crime is high here, partially because of the influx of money from the transit of cocaine passing from South America to the north. The town itself, set between docks and jutting out into the bay on floating restaurants, is not particularly attractive at first glance, with ramshackle buildings and a murky bay. The town’s most interesting attraction is the wood-paneled Moravian Church near the municipal pier, which dates from 1848, although it’s been mostly rebuilt since Hurricane Juana in 1988, which wiped out many of the Victorian buildings that once lined the brick streets. Attached to the church is a cultural museum with Miskito artifacts, including a sword that belonged to the last Miskito king.

The nightlife in Bluefields is raucous, even legendary, and is reason enough to make a trip here. They call Bluefields the Jamaica of Nicaragua, and ‘Maypole,’ a style of tropical calypso with raunchy lyrics and dance moves, is the town’s claim to fame, with the beat blasting at full volume in grungy discos like Four Brothers and Fresh Point. Things get even crazier during Palo de Mayo, a festival that takes place throughout the month of May. The event celebrates when a maypole was erected in the center of town, decorated with ribbons in flowers, during the town’s early days to mark the coming of spring. Today, the festival is an excuse to party, with drunken parades and dancing that goes on until the wee hours of the morning.

Beisbol, Nicaraguan-style

In the 1880s an American businessman named Albert Addlesberg was living in Bluefields, at the time part of autonomous Mosquito territory, which had a strong British influence. Cricket was widely popular in Bluefields at the time and Addlesberg convinced two of the clubs to switch to baseball, giving them equipment he had shipped in from New Orleans. The game caught on and spread all along the Caribbean coast. When the region was incorporated into Nicaragua, the sport spread all around the country.

The first official game was played between Managua and Granada in 1891 and US marines stationed in the country during the early years of the 20th-century helped bring it to the masses. In 1956, La Liga Nicaragüense de Beisbol Profesional (LNBP) was formed and enthusiasm for the sport grew, pushed along by the success of the country’s national team on the world stage and the emergence of Nicaraguan players in the American leagues. The league shut down in 1967 amid economic and political problems in the country. After the civil war, the game picked up again and in 2004 the league was reestablished, with teams in Managua, Masaya, Rivas, Granada, and Chinandega. While stadiums lack funding and players often have second jobs, baseball is considered Nicaragua’s national sport.

Laguna de Perlas

Reached by pangas (small boats) through a network of canals each day from Bluefields (three hours), the town of Pearl Lagoon was once considered to be the second capital of the Miskito Kingdom, after the last Miskito king took up residence after being deposed in Bluefields in 1894. Today, it’s a relaxed fishing village with dirt roads where reggae wafts through the air. Visitors chill in over-water wooden restaurants with thatched roofs, sampling soulful plates of seafood and cheap beer. There are no beaches here; for those, travelers will need to hire a boat to the Pearl Cays (see below). You can visit the Miskito community of Awas, 3km (1.8 miles) west, or the Garífuna village of Orinoco on the other side of the lagoon, reached by boat. The fishing is good here, with opportunities to catch tarpon and snook in the lagoon, plus yellowtail and bonefish in the open sea.

Pearl Cays

Just off the Caribbean coast, 35km (22 miles) northeast of Pearl Lagoon, the Pearl Cays ¤ [map] are the isolated tropical paradise many hope to find in the Corn Islands. Most of the 18 cays – several of which disappear during high tide – amount to nothing more than a patch of palm trees sticking out of white sand, fringed by coral reefs that can be seen through the crystal-clear water. Several of the islands are privately owned, a touchy subject among the Miskito and Creole islanders who live there and claim them as their own. Some of the cays, like Pink Pearl, can be rented out entirely, although the rest can be visited on day trips from Pearl Lagoon.

An eagle ray flies across a coral reef off Little Corn Island.

iStock

From May to November the cays are an important nesting site for the endangered hawksbill turtle, which have traditionally been hunted for their shells. The Wildlife Conservation Society now helps with managing the wildlife on the islands, having trained ex-poachers to protect the nests, from an office in Pearl Lagoon.

Bilwi

In the far north of Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast, not far from the border with Honduras, Bilwi ‹ [map] is an impoverished port town of 50,000 people, half of which live in the dozens of Miskito communities outside of the center. Also known as Puerto Cabezas, the ramshackle town is surrounded by rivers and lagoons, which make for great exploring.

In town, there are a handful of good seafood restaurants, although the most interesting place to eat is the Mercado Muncipal, where there are stands with traditional dishes like rondón (see margin) and coconut bread. The Muelle Viejo, the old pier, which extends 420 meters (1,378ft) into the sea, is worth a sunset stroll. It’s here that the Contras once received smuggled arms; the Somoza government allowed it as a launch point for the failed, US-funded Bay of Pigs invasion. Today, it’s better known as a launch point for artisanal lobster fishermen. Opened in 2001, the Casa Museo Judith Kain (tel: 2792 2225; Mon–Fri 8am–3pm, Sat 1–2pm) is set in a colorful wooden house once owned by a local painter. It now features cultural and historical displays.

Eat

On Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast, one of the most famous traditional dishes is rondón, a anglicism of the words ‘run down,’ describing the search for the ingredients. The slow-cooked stew simmers coconut milk with anything else that is lying around, which usually includes plantains, yuca, fish and shellfish. It was a traditional African dish that was adapted with local ingredients by slaves brought to the region by the Spanish.

The Corn Islands

Two tiny blips of land 83km (52 miles) off of Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast, the chilled out islands of Big Corn and Little Corn are a world of their own. With white sand beaches fringed with palm trees and turquoise water offering the country’s most pristine coral reefs, the Corn Islands › [map] sound as if they are a fictional place. The creole-speaking islanders get by on lobster fishing and harvesting coconuts, with tourism not far behind. Reached by short La Costeña airline flights from Bluefields and Managua to Brig Bay, or a weekly, 5-hour ferry trip from Bluefields, they are just remote enough to avoid an onslaught of tourists. There are no large resorts here and no ultra-luxury rooms whatsoever. Just simple beachside bungalows and no-frills eateries where the kitchens are, more often than not, exposed to the breeze.

A quiet beach on Little Corn Island.

iStock

Big Corn

A single paved road runs the length of Big Corn Island, which is where most tourism in the Corn Islands is concentrated. Brig Bay is home to more than half of the total population of the islands, with nearly 4,000 residents who mostly live in the colorful wooden houses that ring that waterfront. It’s the transportation and commercial hub of the islands.

Many come to Big Corn for the beaches, the most famous being Picnic Bay, in the south. It’s a long, white sandy beach with calm blue water and a couple of simple restaurants. Arenas Beach, home of the 29-room Arenas Beach Hotel (www.arenasbeachhotel.com), is smaller, while Sally Peaches Beach on the northeastern shore features pink sand and shallow pools filled with marine life.

With warm water, undisturbed reefs and year-round good visibility, diving is one of the most popular pastimes in the Corn Islands and prices are as inexpensive as those in the Bay Islands. On Big Corn, the PADI-certified Corn Island Dive Center (www.cornislanddivecenter.com) runs inexpensive dives to sites like Blowing Rock, a pinnacle of giant boulders where nurse sharks are usually spotted, and a 19th-century Spanish galleon off Waula Point.

Little Corn

For those that think there is too much going on over on Big Corn Island, they will love Little Corn. Less than 2km (1.2 miles) long, the tiny isle is accessible by speedboat several times a day from Big Corn Island, an approximately 30-minute ride. There are no cars here, just a patch of jungle circled by clean, clear beaches and one well-trodden footpath. Electricity is scarce here and most accommodations are limited to thatched cabanas. One exception is the chic Yemaya Boutique Hotel (www.yemayalittlecorn.com), on the northern shore, with its own spa and farm to table restaurant.