No country in Central America has entered the 21st century quite as boldly as Panama. The zigzagging economy, still anchored by the canal, which fell under Panama’s complete control on the last day of 1999, is being pushed along by its status as a tax haven, some of it on the shady side, as the Panama Papers revealed in 2016.

Punta Paitillia’s skyscrapers, Panama City.

Getty Images

In Panama City, the skyline has gone from a few skyscrapers to hundreds. The region’s first metro has been installed here and glitzy malls and restaurants are as cosmopolitan as anything in New York or Paris. At first glance, you might mistake the city for Dubai or Hong Kong, but the rainbow-colored buses blasting reggaeton assure you that this metropolis is Latino without a doubt.

Panamax container ship in the canal.

Getty Images

Tourism here is quickly catching up to Costa Rica, though thus far there’s no threat to authenticity or to the rich flora and fauna. The canal is bigger than it once was and sees more cruise traffic than ever before, but much of the country remains free from crowds. Coffee farms around Boquete and hiking trails along the canal zone attract the same birders and java geeks as they always have, while Afro-Caribbean towns like Portobelo and fishing lodges in the Gulf of Chiriquí have remained decidedly low-key. Still, wherever you go, the amenities have gotten better, and a bit nicer. While the Pan-American Highway remains the most popular way to travel from the capital in the east to David in the west, low-cost airlines have cut travel time to remote destinations like Bocas del Toro and the Azuero peninsula, where new beach hotels and eco-chic resorts are opening by the handful.

Culturally, the country of 4 million is also rich. In remote mountain ranges and tropical isles, indigenous groups like the Emberá and Kuna carry on their traditions. Elsewhere, the country’s genetic make-up has been altered by waves of immigrants, from the Spanish conquistadors to the Jamaicans and Italians and Americans that came for the canal to the recent surge of retirees and Venezuelans seeking better opportunities.

Panama City has a thriving financial center.

iStock

A new era begins

A new era in Panama began on December 31, 1999, when the US formally transitioned all operations of the Panama Canal to Panama, as well as turned over all military bases. The act was more than 20 years in the making, beginning in 1977 when US President Jimmy Carter signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaty that gave Panama increasing control of the canal until the date of a complete US withdrawal.

While there were fears that the Panamanians would not be able to maintain operations and security on the strategic waterway, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) have eased all concerns. From the first year under Panamanian control to 2016, income increased from $769 million to $2.6 billion. Accidents have dropped, traffic has increased, and expenses have increased less than revenue. In 2016, the canal completed a $5.25 billion expansion that took 10 years to build, giving it the ability to accommodate many of the world’s largest cargo vessels (for more information, click here).

The return of corruption

In 2004, the Democratic Revolutionary Party’s Martin Torrijos won the presidency, campaigning on promises of ending corruption. Torrijos immediately went to work passing laws that made the government more transparent, though there was little follow through when high profile cases appeared.

Succeeding Torrijos was Conservative supermarket magnate Ricardo Martinelli, who won a landslide 60 percent of the vote in 2009. Voters had feared that the world financial crisis was already slowing Panama’s rapid growth rate of previous years and Martinell’s business experience could come in handy. His pro-business policies helped the annual GDP to increase by more than 10 percent each year, turning Panama into one of Latin America’s fastest growing economies, projected to be the fastest-growing in 2017. However, Martinelli proved to be far from perfect. Many in his administration, including his sons, have been investigated or charged with accepting millions in bribes from Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht S.A., which became an important government contractor during that time.

Martinelli was followed by his former political partner Juan Carlos Varela in 2014, amidst a sudden dip in the economy. Not long after being sworn in, the Panama Papers scandal broke. The vast data leak from the Mossack Fonseca law firm detailed how the world’s wealthy stashed assets in offshore companies. While the Varela administration claimed to be strengthening controls over money laundering in Panama and appointed an independent investigation, they have refused to make the final reports to be public. As investigations into Mossack Fonseca continue, the extent of the political fallout might not be understood for some time.

Casco Viejo’s colorful streets.

iStock

Fact

During the 19th century California Gold Rush, thousands of forty-niners crossed the isthmus of Panama as a shortcut from the East Coast of the US to California, rather than sailing around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America.

Panama City and around

Founded in 1519 by Pedro Arias Dávila, Panama City 1 [map] is the oldest Spanish settlement on the mainland of the Americas. The original settlement was where gold and silver being raided from South America was unloaded at sea and then transported over the isthmus by road to the Caribbean, attracting the attention of treasure-hungry pirates. By 1673 the settlement had been destroyed by attacks and then rebuilt in in present day Casco Viejo, which became heavily fortified, ensuring the city could withstand any further attacks. It lingered in obscurity until Panama seceded from Colombia and was designated the capital in 1903. When the canal was built in 1914, it became the center of trade and commerce in the Americas.

Bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the southeast and the Panama Canal to the west, Panama City sprawls out in a maze of congested neighborhoods that rarely follow any sort of order. While few parts of the Panamanian capital are walkable, Casco Viejo A [map], also called Casco Antiguo, is an exception. Declared a World Heritage Site in 1997, Casco is the oldest part of the city and by far the most atmospheric. Over the past two decades, the neighborhood’s stock of centuries-old Spanish, Italian, and French-influenced architecture has been gradually restored, transforming it from a gritty barrio to one of the most gentrified areas of the city. While some parts of Casco still can be quite dangerous, the bulk of the peninsula is home to boutique hotels, pulsating rooftop bars, and a wide range of upscale stores and restaurants.

Plaza de la Independencia, where Panama declared its independence from Colombia, is flanked by several interesting sights: the neoclassical Catedral Metropolitana (hours vary; free); the Museo del Canal Interoceánico (tel: 211 1649; http://museodelcanal.com; Tue–Sun 9am–5pm), which was built in 1875 and was used as offices for the French and later US canal, and now contains historical documents and artifacts related to the construction of the canal; and the Hotel Central (tel: 309-0300; www.centralhotelpanama.com), once the most luxurious hotel in the region before being neglected for decades and finally restored to glory in 2016. Down Calle 6a Este is the Presidential Palace, a stunning Spanish mansion with a Moorish interior patio, inaccessible to tourists.

A few blocks to the northeast is Plaza Bolívar, home to the Palacio Bolívar, which contains the Salón Bolívar (Tue–Sat 9am–4pm), a room that hosted the 1826 congress organized by liberator Simón Bolívar to discuss the unification of Colombia, Mexico, and Central America. The building is now the home of the Ministry of Foreign Relations. Next door is one of the oldest buildings in Casco, the Iglesia y Convento de San Francisco de Asís (hours vary; free), although much of it was destroyed in a series of fires in the mid-1700s. At the corner of the plaza is the Teatro Nacional (tel: 262 3525; hours vary; free), dating to 1908 and designed by Italian architect Genaro Ruggieri, which hosts opera, theater, and other performance art. Inside are frescoes by renowned Panamanian painter Roberto Lewis.

Plaza de Francia, on the southeastern corner of Casco, is sided by Las Bóvedas, a series of jail cells that have been restored and now contain several upscale stores and cafés. Leading from the plaza is the colonial-era stone promenade Paseo Esteban Huertas, where several Kuna women sell handcrafted molas.

Plaza Herrera on the western side of Casco is home to several important hotel projects, including the American Trade Hotel (www.acehotel.com/panama) that was created in the 1917 neoclassical headquarters of the American Trade Developing Company.

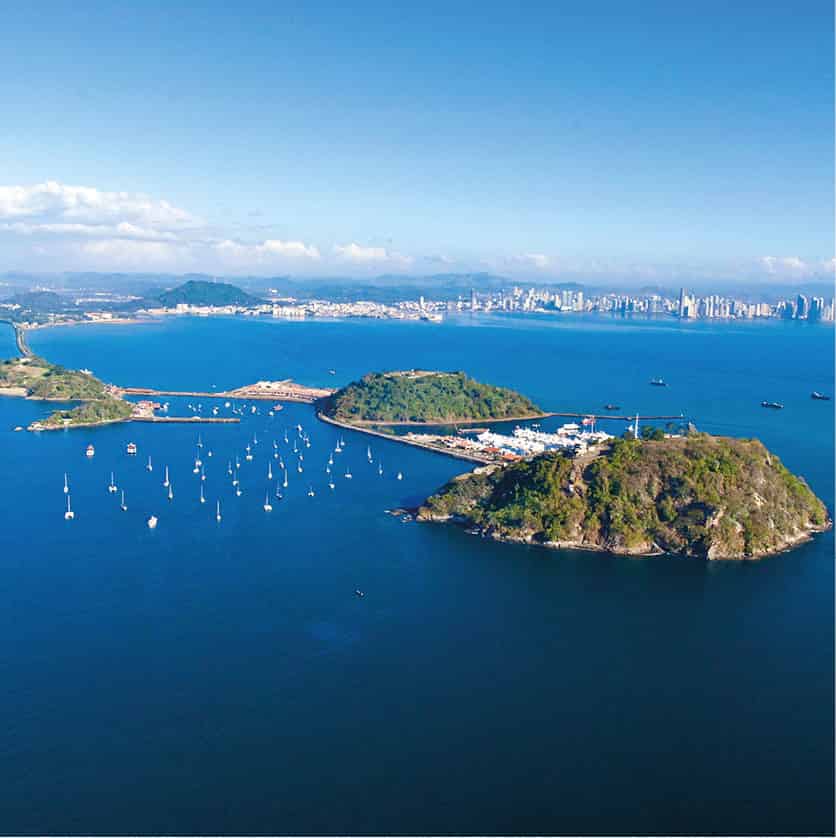

Aerial view of Amador Causeway.

iStock

The Amador Causeway

South of Casco, extending into Panama Bay, is the Amador Causeway B [map], which connects the four tiny islands of Naos, Culebra, Perico, and Flamenco. These islands, connected with the dirt and rock that was excavated during the Culebra Cut, form a protective harbor for ships waiting to enter the Panama Canal. It was a military zone used by the US until the handover in 1999, when the government opened it to the public. It’s now a popular walking and jogging trail and the home of several major projects.

First and foremost is the Frank Gehry designed BioMuseo (www.biomuseopanama.org; Tue–Fri 10am–4pm, Sat–Sun 10am–5pm), a $100 million biodiversity museum that took a decade to build. It is notable for its multicolored roof plates and eight different interior galleries, each displaying a different piece of the formation of the Panamanian isthmus. Farther down the causeway, at the Smithsonian’s Tropical Research Institute, is the Punta Culebra Nature Center (www.stri.si.edu/english/visit_us/culebra; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm, Mar–Dec Tue–Fri 1–5pm), where visitors can explore the marine and coastal environment on trails through the tropical dry forest and various exhibitions of native flora and fauna.

The Modern City

To the northeast of Casco Viejo, running along the coast, are a string of neighborhoods like Marbella, Bellavista, Punta Paitilla, and Punta Pacífica C [map] that are nearly indistinguishable from each other. They are dominated by a sea of glitzy glass and steel skyscrapers where the city’s wealthiest residents live, and which seems to grow more dense every month. Running along the waterfront is the Cinta Costera D [map], a green space with a cycling and jogging path.

The interior neighborhoods of El Cangrejo, Obarrio, and the Area Bancaria form much of the city’s business and financial district, though residential and hotel projects are also concentrated here. San Francisco to the north is where the city’s best dining can be found, such as at renowned contemporary restaurant Panamanian Maito (www.maitopanama.com). Albrook E [map], to the south, is home to the domestic airport and bus terminal and more residential, home to wooden houses with wide verandas that were built during the days of US control of the canal.

Cerro Ancón F [map], a jungle-clad hill close to Casco, has a 360-degree view of the city. Aside from the more residential lower slopes, the reserve is mostly undeveloped and it’s possible to encounter animals like sloths, armadillos, coati, and Geoffrey’s tamarins.

Panama Viejo

The original settlement of Panama City, Panama Viejo G [map] (www.patronatopanamaviejo.org; Tue–Sun), founded by the conquistador Pedrarías Dávila in 1519, was burned down after being sacked by Henry Morgan in 1671. At the time, there were as many as 10,000 people living there, though thousands died in the attack. When the settlement was moved a few kilometers west to present day Casco Viejo, which could be better defended, much of the stone went with it.

The ruins today, a Unesco World Heritage Site, are hidden within the encroaching jungle and are largely surrounded by modern suburbs. The restored Plaza Mayor and a bell tower from what was Panama’s original cathedral form most of what remains today, along with a few walls and minor buildings. The visitor center has a model of the city before it was destroyed, as well as a few colonial artifacts.

Ruins of Panama Viejo.

Shutterstock

Isla Tabogo and Las Perlas

Reached by daily ferries from the Amador Causeway, Isla Taboga 2 [map], known as the ‘island of flowers,’ is the nearest offshore island to Panama City. Just 19km (12 miles) off the coast, it’s an easy day trip with a few good beaches like Playa Restinga and laid back restaurants.

Farther out is the Archipiélago de Las Perlas 3 [map], 64km (40 miles) from Panama City, reached by ferry or a 20-minute flight. There are more than 200 small islands here, the majority of which are uninhabited. Fine snorkeling, big game fishing, and unspoiled beaches are all found here and while there have been rumblings about development in recent years, it hasn’t happened yet.

The most developed island is Contadura, which has dozens of small hotels and B&Bs. The island has gained a reputation for its celebrity guests, which include models, fashion designers and even the former Shah of Iran, who have built luxe mansions here. Contadura boasts 13 beaches like the popular Playa Galeón and Playa Ejecutiva on a quiet cove.

Fact

The French attempt at building the Panama Canal, lead by Suez Canal architect Ferdinand de Lesseps, was a disaster. Few foresaw the enormous challenges that the thick, mosquito-infested jungle presented, ranging from floods to yellow fever. In the end, more than 20,000 died before they called it quits.

Rainforest aerial tram, Gamboa Rainforest Resort.

Getty Images

The Panama Canal

Extending 77km (50 miles) from the Port of Colón on the Caribbean Sea to the Port of Balboa near Panama City, the Panama Canal 4 [map] is the world’s most strategic waterway. More than 14,000 vessels pass through it annually, representing around 5 percent of global trade. Considered one of mankind’s grandest feats of engineering, the canal is without a doubt Panama’s major attraction.

Aside from sailing through the canal, as many cruise passengers do, the easiest way to see the canal in action is at the Miraflores Locks, a 20-minute drive from Panama City. The Miraflores Visitors Center (tel: 276-8325; www.visitcanaldepanama.com) overlooks the locks from four levels, each with different exhibitions and interactive displays, including a 3D movie theater with films detailing the history of the canal. The best time to visit is around 11am or around 3pm, when enormous Panamax ships can be seen rising and falling as they traverse the locks. Crowds gather on the observation decks as an announcer details information about the ship, such as where it is registered and where it is going. The Atlantic & Pacific Co. Restaurant (www.atlanticpacificrestaurant.com; daily 9am–4.30pm) serves a pricey buffet where you can drink champagne and watch as the ships move through the locks.

Overlooking Gatún Lake and the new Atlantic-side locks closer to Colón, which were built during the expansion of the canal, the Aguas Claras Visitor Center (daily 8am–4pm) is less formal than its Miraflores counterpart. There is no site museum and just a small theater, but most come here simply for the view of the ships passing through.

Cruise ship passing through Gatun Locks.

Shutterstock

The expanded Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is now even bigger than before. A $5 billion-dollar expansion added a new lane and room for the world’s largest ships, allowing for nearly double the amount of traffic.

For much of the past century the shipping industry has built ships to fit through the Panama Canal, often referred to as the 8th wonder of the world. Mostly oil tankers, they’re called Panamax ships. However, by the 1990s, the size of the canal was becoming outdated as ships grew bigger and bigger. Many were far too large to enter the canal, resulting in a significant loss of market share to the Suez Canal. And so, to avoid the risk of the canal becoming obsolete, the Panama Canal Authority began work on an expansion project in 2007. A national referendum to ratify the plan was approved by a 76.8 percent majority.

The larger canal, which began operations in June 2016 (after being more than two years behind schedule and $1 billion over budget), added an entire new lane of traffic, doubling the capacity of the canal. It took roughly 40,000 workers nearly 10 years to complete the massive infrastructure project, which rivals the statistics of the original canal build that took place a century before. Enough earth was dredged to fill the Great Pyramid at Giza 25 times over and there was enough steel used that they could have built 29 Eiffel Towers.

Parallel to the old locks, two new locks were built: one east of the existing Gatún locks, and one southwest of the Miraflores locks. These new locks are wider, at 54.8 meters (180ft) versus 33.5 meters (110ft), and deeper, at 18 meters (60ft) versus 12.8 meters (42ft), allowing larger ships to transit. These are called New Panamax and are about one and a half times the previous limit, with the ability to carry twice as much cargo. As the canal was expected to hit capacity between 2012 and 2014, the expansion was designed to allow for an anticipated growth in traffic from 280 million PC/UMS tons in 2005 to nearly 510 million PC/UMS tons in 2025. The total cost of the project is estimated to have been $5.25 billion. As a result of the increase in traffic, ports around the world – from the east coast of the US to the UK and Brazil – expanded their capabilities in preparation for the new, larger ships.

Transiting the canal

While many are content to watch these colossal New Panamax ships pass through the canal at the Miraflores Locks, a quick jaunt from Panama City, many choose to transit the canal. Moving from the Atlantic to the Pacific Coast and vice versa, it takes between 6 and 8 hours to transit the entire canal, passing through all three locks: Miraflores, Pedro Miguel, and Gatún. While many passengers traverse the canals on cruise ship itineraries, partial tours of the canal are an alternative for visitors in the country. As transiting each lock can take upward of two hours, it grows tiresome for the full journey, so many tours simply offer excursions passing through the Pedro Miguel and Miraflores locks, followed by sailing under the Bridge of the Americas and into the Pacific Ocean. The 300-passenger Pacific Queen runs frequent trips from Gamboa to the Pacific via Panama Marine Adventures (www.pmatours.net), while the 100-person wooden Isla Morada and 500 passenger steel Fantasía del Mar run between the Flamenco Marina and Gamboa or Gatún.

Elsewhere in the Canal Zone

Along the edge of the eastern side of the Panama Canal is one of Panama’s most astounding natural areas, the 19,425 hectares (48,000 acres) of Parque Nacional Soberanía 5 [map] (daily 6am–5pm). Just 40 minutes from the city, Soberanía is one of the most accessible natural areas in Central America and it’s been extremely well preserved. More than 100 species of mammals have been identified here, including jaguars, sloths, and monkeys, not to mention more than 500 species of birds. From the park ranger station there are several trails into the park of varying levels of difficulty. Closer to Gamboa is the renowned birdwatching spot, Pipeline Road.

There are several ecolodges within or on the border of the park, such as Canopy Tower (www.canopytower.com), which opened in 1999 in an ex-US-military radar station on top of Semaphore Hill. Topped by a 9 meter (29.5ft) high dome, views of the rainforest canopy give phenomenal access to bird watchers, making the lodge one of the region’s top destinations.

Gamboa, once a residential area for American workers in the canal’s dredging division, is on the shore of the Chagres River and home to the Gamboa Rainforest Resort (www.gamboaresort.com), a family-friendly lodge surrounded by the pristine forests of Soberanía. Less ecolodge than posh hotel, it’s a sprawling property that includes multiple pools and restaurants, plus a full range of in-house excursions like boat trips on Gatún Lake and guided hikes with naturalist guides.

Gatún Lake 6 [map] was created in 1913 when the Gatún Dam was built on the Chagres River, flooding 425 sq km (164 sq miles) of forest. The lake is home to several Emberá villages, which resettled here near the mouth of the Chagres River from the Darién Province. The villages of Parara Puru, Emberá Puru, and Emberá Drua have opened to tourism and visits have become a popular shore excursion for cruise visitors and other travelers in Panama. Most trips are half-day visits that include a typical Emberá lunch, a folkloric dance show, dugout canoe rides, and the chance – or pressure, some might say – to purchase indigenous handicrafts. Most tour agencies in Panama City, including Ancon Expeditions and Advantage Panama, run tours here.

Fact

While Panama hats were popularized by Ferdinand de Lesseps during the French canal effort, and later Theodore Roosevelt during the American one, they aren’t actually Panamanian. Rather, they’re made in the Manabí Province of Ecuador, using fibers from the toquilla palm, and have been a cottage industry since the 1600s. Lightweight and breathable, the hats were given to canal workers and have become associated with tropical locales.

Cargo ship on Gatún Lake.

iStock

Colón province

Running along Panama’s central Caribbean coast, the province of Colón seems to have a culture all of its own. The Afro-Panamanian influence is strong here, deriving from workers who arrived to work in the canal and those who then arrived during the days of slavery. The gritty capital is the city of Colón, the largest duty-free zone in the Americas, which has undergone a series of makeovers that have yet to truly clean it up. More remote are attractions like the Spanish Fort of San Lorenzo and the historic seaside village of Portobelo.

Colón and around

Founded in 1850 during the California Gold Rush, when crossing the isthmus via the Panama Railroad saved a trip around Cape Horn, Colón 7 [map] has seen its ups and downs. The city grew large in its early days, until its progress was halted by the establishment of the US transcontinental railroad in 1869. It then saw another bump thanks to French and later, American, canal work. It was during this period that much of the city was built, although the city has lingered in obscurity as Panama City has grown.

The city’s biggest industry is the Colón Free Zone on the southeastern edge of town. Here, nearly 2,000 showrooms sell a variety of goods tax-free, although it’s of little interest to passing tourists as it’s primarily aimed at wholesalers. Along the eastern shore is the cruise-ship port, Colón 2000, which has a few restaurants, a duty-free store, and handicraft shops. Much of the rest of the city can be dangerous and is best avoided.

Along the lake shore outside of town is the former Escuela de las Americas, a notorious military school known for training Manuel Noriega. It’s now an upscale Meliá hotel (www.meliapanamacanal.com).

Near the Caribbean entrance to the canal, 10km (6 miles) west of Colón, are the Gatún Locks, which have their own visitor center (daily 9am–4pm). While the facility lacks the amenities of the Miraflores Locks (for more information, click here), the viewing platform gives a great look at Panamax ships and tankers rising to the level of Lake Gatún. About 2km (1.2 miles) farther on is the Gatún Dam across the Chagres River, which was the largest in the world at the time it was built.

Passing over the Gatún Locks, the road leads through the dense jungles of the Sherman Forest Reserve to Fort Sherman, a former US military base that has been partially dismantled. The rough road continues 8.9km (5 miles) until the mouth of the Chagres River. Nearby, you will find Fort San Lorenzo (daily 9am–4pm), a Spanish fort that was first built in 1595, but sacked several times in pirate attacks. The current incarnation, a Unesco World Heritage Site, dates from 1761 and is in a relatively good condition, with a collection of rusty cannons and a grass covered moat.

The ruins of Castillo Santiago de la Gloria, Portobelo.

Getty Images

Portobelo to Isla Grande

Approximately 43km (27 miles) east of Colón lies the sleepy seaside town of Portobelo 8 [map], which was one of the wealthiest ports in the Spanish Caribbean from the 16th to early 18th centuries, thanks to much of the silver and gold from South America passing through here before being shipped off to Europe. Portobelo today is relaxed as they come, a small grid of cobblestone streets fronting the yacht-filled bay, with jagged, rainforest covered mountains towering behind it.

Buccaneers like Henry Morgan and the British Admiral Edward Vernon made their mark on the city, and as a result, defensive fortifications were built around the bay. Much of the original architecture has been well preserved, helping Portobelo attain Unesco World Heritage Status in 1980. Fronting the plaza is the Customs House, dating to 1630 but partially rebuilt after cannon attacks and a fire over the centuries. It is said that one third of the gold in the world once passed through its door, and today it’s a small museum. Beside the Customs House is Fuerte San Jerónimo, which dates back to 1664 and features a row of cannons facing the bay.

The Iglesia de San Felipe (hours vary; free), a block from the plaza, is home to the celebrated ‘Black Christ’ statue, which is honored with a festival each October 21. The statue was, as legend has it, left behind by a ship en route to Cartagena and after residents prayed to it during a cholera epidemic they were miraculously spared.

The quaint village is as rich culturally as it once was economically. The residents are descendants of African slaves brought during the Spanish colonial era, who call themselves ‘congos.’ They maintain rich expressions of dance, music, and art, which come alive during festivals throughout the year. An art gallery and cultural center called La Casa Congo (www.fundacionbp.org), which is associated with the luxury hotel El Otro Lado (www.elotrolado.com.pa) across the bay, helps organize performances for visitors and rents kayaks, to explore the mangroves and fortifications that can only be accessed by water.

Roughly 20km (13 miles) east of Portobelo in La Guaira, just beyond Adriana’s Afro-Panamanian seafood restaurant, boats run offshore to Isla Grande, a relaxed island escape with a few good beaches and decent snorkeling. There are a few small hotels and restaurants, which open and close with the seasons. Amenities here are quite basic.

A traditional congo dance in Portobello.

Shutterstock

The Pacific coast

West from Panama City, the Pan-American highway runs parallel to the Pacific coast, passing a string of beaches that become progressively more attractive the farther away you get from the capital. Many wealthy Panamanians and ex-pats have beach houses or condos here, which usually remain empty during the week. Seaside golf courses and a few mega-resorts are scattered about as well. The landscape becomes more rugged at the Azuero Peninsula, a cowboy country known for wild parties, that’s seeing its first signs of major development on its more remote beaches. At the Gulf of Chiriquí, the coast is at its most dramatic, with wild islands and fine whale-watching.

Drink

Some mistake rum for Panama’s national drink. It’s not. That honor belongs to seco, a thrice distilled, 80-percent-proof sugarcane liquor. The most famous brand is Seco Herrerano, produced in the town of Pesé, by the Varela Hermanos distillery, which dates to 1936 and coincidentally also makes Abuelo rum. While inexpensive, top bartenders in Panama City have been experimenting with seco, often macerating it in native fruits.

Tourists on the beach at Santa Clara.

Shutterstock

Near Pacific Beaches

The nearest beach to Panama City is Playa Bonita, just beyond the Bridge of the Americas, where there is a mega-resort, the Westin Playa Bonita Resort & Spa (www.starwoodhotels.com), though little else. The lengthy beach at Playa Coronado, 83km (51 miles) from the city, is one of the most developed on the coast, with supermarkets and lots of residential units. Coronado feels older, yet not nearly as cookie cutter in style as some of the developments farther west.

Santa Clara 9 [map], 113km (70 miles) from the city, and neighboring Farallón are the prettiest beaches on the coast and attract more tourists than locals. Santa Clara is more public, with condo towers and mostly small hotels, aside from the all-inclusive Sheraton Bijao Resort (www.starwoodhotels.com). Farallón, which is better known as Playa Blanca, is home to the massive, 852-room Royal Decameron Beach Resort, Golf, Spa & Casino (www.decameron.com), as well as the Buenaventura complex, anchored by a JW Marriott hotel and a Jack Nicklaus-designed golf course that is one of the best in Central America.

El Valle de Antón

Inland, 28km (17 miles) from the Pacific, is El Valle de Antón ) [map], aka El Valle, which sits within the crater of the world’s second-largest extinct volcano. With an altitude peaking at 762 meters (2,500ft), El Valle has year-round cooler conditions than the coast, making it an attractive weekend escape from Panama City, less than two hours away. On Sundays, vendors from around the region come to town to sell handicrafts and produce, including Ngäbe and Emberá people, who sell traditional cloths and baskets.

Lush and green, the town and surrounding forests are a biodiversity hotspot and more than 350 species of birds have been recorded here. Cerro Gaital National Monument, on the northern hillside of town, has good hiking trails, including a 2–3 hour loop, where you can see both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans from certain points.

There are dozens of B&Bs and ecolodges on the outskirts of town, including Canopy Lodge (www.canopylodge.com), which runs a zipline track farther up the hill, and the more resort-like Los Mandarinos Hotel and Spa (www.losmandarinos.com). For dining, there’s La Casa de Lourdes (www.lacasadelourdes.com), set inside an upscale Tuscan-style manor house, run by Lourdes Fábrega de Ward, a chef who studied with Martha Stewart and Paul Prudhomme and is something of a Panamanian culinary celebrity.

Girls marching in a parade in Chitré wearing traditional pollera costumes.

Shutterstock

Roughly 100km (60 miles) wide and 90km (55 miles) long, the Azuero peninsula is located just southward off the Pacific Coast, splitting the Gulf of Panama and the Gulf of Chiriquí. The rugged interior is defined by bare, rolling hills with grazing cattle and the occasional Spanish colonial house, while the pristine coastline is relatively undeveloped, although that is quickly changing. This is the folkloric capital of Panama, with a hard partying Carnaval and the finest makers of Pollera dresses.

The largest town on the Azuero peninsula is Chitré ! [map], which has a small airport with daily flights to Panama City. The town is of little interest, outside of amenities such as modern hotels and grocery stores that are severely lacking in other parts of Azuero. Outside of town is La Arena, an artisan village known for its ceramics, particularly the painted pots called tinajas.

Comprised mostly of whitewashed adobe houses with clay tile roofs, Las Tablas @ [map] is one of the most atmospheric towns in Azuero. For much of the year it is a sleepy place where there is little to do other than soak up the atmosphere…until Carnaval comes along. While the holiday is celebrated all over Azuero, in Las Tablas it is downright maniacal. Beginning on the Saturday before Ash Wednesday and continuing for four days of parades, pollera contests, pageants, and, of course, heavy alcohol consumption. Throughout the event, the battle lines are drawn between Calle Arriba and Calle Abajo, which choose their own queens and try to out-do each other with floats and costumes. Water pistols, hoses, and buckets have become quite common, so visitors should plan on getting wet, whether they would like to or not.

The cowboy town of Pedasí £ [map], driven by a young mayor who has encouraged the community to spruce up the local colonial houses, is becoming increasingly gentrified. There are new cafés and boutique hotels, although horses still far outnumber BMWs here. The town is the jumping-off point for the sudden surge of development on Playa Venao, about 12km (7 miles) away. With its long, curved beach and consistent waves, a new community is beginning to form, much of it from Israeli investments that are pumping cash into modern hotels like Villa Marina (www.villamarinalodge.com) amidst the surf camps and yoga retreats. On the south end of the beach, there’s the renowned restaurant Panga, run by an ex-Top Chef contestant who cooks over a wood fire, forages for local produce, and works with sustainable fisherman to create surprisingly sophisticated yet affordable meals.

The polleras of Azuero

The complexly designed pollera costumes are widely considered to be one of the world’s most beautiful forms of traditional dress. While the Spanish colonial dress was common in haciendas throughout Latin America, the most famous polleras come from the Azuero peninsula. Worn during special occasions, these polleras consist of a one-piece skirt layered with petticoats, which are intricately embroidered with floral designs and trimmed with lace. Accessories include gold and pearl jewelry called mosquetas and tembelques, which are passed down from one generation to the next. Each dress takes months to make and they can cost thousands of dollars. Panamanian women generally own two polleras in their life: one before they are 16 and another in adulthood.

Founded in 1994, the 14,730 hectares (36,400 acres) of Chiriquí Chiriquí Gulf National Marine Park $ [map] is where Panama is found in its most raw and wild form. The land, much of it displayed on uninhabited islets, is jagged and green, hiding big game fishing lodges and tiny resorts. In and along the water are mangroves, coral reefs, and white-sandy beaches. Huge schools of tropical fish, whales, and white-tipped sharks all come here to play in the sea, while migrating seabirds share the thick vegetation with howler monkeys and other wildlife.

The isolated fishing community of Boca Chica provides the best access to the park. Here, small hotels like Bocas del Mar (www.bocasdelmar.com), and nearby fishing lodges such as the Panama Big Game Sportfishing Club (www.panama-sportfishing.com) on Boca Brava island, set up packages where you can fish, kayak, whale-watch, or just lie on the beach.

Looking out over the Coiba archipelago.

Alamy

Isla Coiba

Panama’s largest island, Coiba % [map] (www.coibanationalpark.com) is one of the most pristine natural areas anywhere in Central America. The Coiba National Park encompasses 38 islands and islets, not to mention the waterways between them, extending to 270,128 hectares (667,500 acres), leading some to call it the region’s Galapagos. Primarily reached on day trips from the town of Santa Catalina, the park is home to the second-largest coral reef in the eastern Pacific, which is teeming with whales, hammerheads, nurse sharks, manta rays, crocodiles, and sea turtles, plus another 36 species of mammals on land. For almost 90 years, until 2004, there was a penal colony on Isla Coiba, which kept most tourists and developers away. Now that it’s gone, tourists are slowly arriving to dive the waters at Granito de Oro and hike the jungle trails of Coiba.

Fact

The bajareque is a unique weather phenomenon that occurs from December to March, when a fine misting rain is pushed over from the Atlantic and into the highlands. The mist is so soft it ‘caresses the face,’ as locals like to say. The combination of sun, wind, and bajareque provides endless rainbows.

The Chiriquí Highlands

Adventure seekers, bird-watchers, and coffee geeks are quickly discovering Panama’s highest mountains. The Chiriquí region, which has seen a surge of expats buying homes and opening businesses, is quickly becoming one of the most exciting destinations in Panama. It is rich in biodiversity, with the region’s unspoiled forests home to hundreds of rare birds, such as the resplendent quetzal and blue cotinga, while raging rivers are ideal for rafting and cloud forest trails that few have trodden await.

David

The transportation hub of western Panama and the country’s third largest city, David ^ [map], a 45-minute drive from the Costa Rica border, is surprisingly flat. Set in the sweltering heat of the coastal plain, many only fly here or get off a bus before heading straight up the mountain to explore the cooler climate. Still, the town, while spread out, has a few blocks of colonial charm at Barrio Bolívar, and there are fine dining restaurants like Cuatro and swanky old hotels like the Gran Hotel Nacional (www.hotelnacionalpanama.com), which has added a quirky casino and movie theater complex.

Finca Lerida, a coffee plantation in Boquete.

Getty Images

Volcán and around

On the lower slopes of the Barú Volcano, the town of Volcán & [map] is characterized by its alpine-like climate and patches of small farms that surround a modern, bustling center. It’s a good base for exploring the highlands and sits in close proximity to several major attractions.

About 5.5km (3 miles) southwest of Volcán is Sitio Barriles (daily 7am–5pm), one of Panama’s few Pre-Colombian archeological sites. Discovered on the private land of the Landau family as they were building a coffee plantation, the site was once home to the Barriles culture, which was based in the area from 600–300 BC until the eruption of Barú forced them out. Hundreds of tools, ceramics, and a burial tomb with funerary urns have been found here, although only some of the finds are on display.

The rich volcanic soil surrounding Volcán has turned it into a haven for coffee farmers, and several offer tours of their plantations. Just west of town, the Janson Coffee Farm grows eco-friendly, organic beans that are handpicked and roasted in small batches, a process that can be seen on several short tours, run by Lagunas Adventures (tel: 6569-7494; www.lagunasadventures.com), of their plantation and production facility. More remote is Finca Hartmann (tel: 6450-1853), near the town of Santa Clara, 27km (17 miles) from Volcán. The stunning setting within the dense forests is a favorite for its birdwatching, as it sits in the north–south corridor of migrating birds. Short tours of the coffee production facilities are offered, though bird-focused visitors will often stay for a few days to camp out in the finca’s rustic cabins and hike through an extensive network of trails through the plantation.

The small but popular town of Boquete.

iStock

Boquete and around

The major tourist destination in Panama’s highlands is without a doubt, Boquete * [map], which has attracted a diverse population of North American and European expats who have moved here by the planeload to take advantage of the year-round, spring-like climate. On the shore of the Caldera River and backed by the steep slopes of the Barú volcano, the town itself is quite charming and provides easy access to numerous adventure activities and coffee fincas.

Boquete and its immediate surroundings are full of interesting amenities like the Boquete Brewing Company (www.boquetebrewingcompany.com), the Café Kotowa coffee shop, and Boquete Bees (www.boquetebees.com), a coffee farm and honey plant that produces gourmet honeys from native pollinators. There is a better selection of accommodations in Boquete than just about anywhere in Panama, ranging from the rustic Panamonte Inn & Spa, which dates from 1914 and is home to renowned chef Charlie Collins, to the posh Finca Lerida (www.fincalerida.com), on one of the region’s most historic coffee estates.

Some of Boquete’s most spectacular scenery is located on the hills above town, best reached by car. The paved Bajo Mono Loop, taking a left past the church at the end of town, gives phenomenal views of town below, as does the Volcancito Loop, reached by making a right after the CEFATI visitor center. On the main highway heading toward the Caribbean coast, the route winds through the lush forests to Finca La Suiza, set out over 81 hectares (200 acres). The property is intersected by three lengthy hiking trails through cloud and tropical forests that are home to waterfalls and spectacular vistas.

Outside of Boquete

What Panama lacks in volume in terms of coffee, it makes up for it in quality. Shade-grown varieties grown in the rich volcanic soil have given Panama a name in the premium coffee market, surging past the better-known Costa Rica. In particular, it’s the varietal called Gesha, or Geisha, a plant of Ethiopian origins that mutated in Boquete’s climate, giving it tea-like qualities that have helped make it the most expensive coffee in the world. One of the oldest producers in the region, Casa Ruiz (www.caferuiz-boquete.com), offers guided tours led by Ngäbe-Buglé guides on Mon–Sat. It’s the largest operation in the area. Café Kotowa (www.kotowacoffee.com) was founded more than a century ago by a Scottish immigrant whose original water-powered mill is now where they hold their cuppings at the end of the tour. Finca Lerida, mentioned above, also offers tours to non-guests.

The Chiriquí Highlands offer some of the best whitewater rafting in Central America, ranging from intense Class III to V kayaking and rafting to relaxed floats, to take in the mountain landscape. The Chiriquí River, and more remote Chiriquí Viejo River, feature the most technical whitewater, with Class III to Class V rapids. These rivers can only be rafted from July to November when water levels are high. The Class II Esti River is the tamest experience, suitable for families with young children, while the Class II-III Gariche River is slightly more technical. Two rafting agencies run trips: Chiriquí River Rafting (tel: 720-1505; www.panama-rafting.com) and Boquete Outdoor Adventures (tel: 720-2284; www.boqueteoutdooradventures.com).

Car with tourists on a trail to the top of Volcán Barú.

Shutterstock

Volcán Barú National Park

Covering the Pacific side of the 3,475m (11,500ft) extinct Barú Volcano, the highest point in Panama, the Volcán Barú National Park ( [map] is one of the most well-trodden in Panama, for good reason. Encompassing 14,000 hectares (34,600 acres) of primary and secondary forest, the park is a biodiversity hotspot with rare flora and fauna that includes more than 250 species of birds, like the resplendent quetzal and the three-wattled bellbird, plus giant oak trees that are hundreds of years old, and dozens of species of orchids that aren’t found anywhere else. Entrance fees are paid at the ranger stations of the Los Quetzales trailhead 8km (5 miles) from Boquete at Alto Chiquero, as well as on the other side, closer to the higher altitude Cerro Punta at El Respingo.

Overwater villas at Punta Caracol Hotel, Isla Colón.

Getty Images

Bocas del Toro

Near the border with Costa Rica, the archipelago of Bocas del Toro , [map] is comprised of seven islands and another 200 or so islets renowned for their unspoiled beaches and laid back, Caribbean vibes. The English-speaking islands have become ecotourism hotspots, with isolated rainforest lodges and over-water bungalows where snorkeling and surfing are as easy as rolling out of a hammock. Much of the archipelago is uninhabited, aside from the pastel-painted houses on Isla Colón and a few Ngäbe-Buglé communities farther afield, allowing the trickle of tourists to live out their tropical fantasies.

Isla Colón

The hub of all activity in the archipelago, the 62 sq km (24 sq mile) Isla Colón is home to Bocas Town, the regional capital. Much of the town’s infrastructure dates from the early 1900s, when United Fruit arrived to install banana plantations on the islands, attracting thousands of immigrants from Jamaica and the Colombian islands of San Andrés and Providencia. The town thrived until the 1930s, when banana blight forced the plantations to move to the mainland; it wasn’t until recent decades, when tourism picked up, that any sort of development returned.

Bocas Town sits on a small peninsula with a bustling waterfront where boats to the mainland at Almirante or Changuinola closer to the border can be found, as well as boats to other islands. The airport, just outside of town, offers daily flights to Panama City and David.

While upscale travelers usually head straight for the eco-resorts on more remote islands, backpackers tend to base themselves within the town’s weathered wooden houses, which have been converted into quaint hotels, funky restaurants and yoga studios. The only nightlife in the island’s is concentrated here and the less developed Isla Carenero, often on bars set on decks over the water. There are several surf schools based in Bocas Town, such as Mono Loco, as well as PADI certified dive schools, like Bocas Dive Center (www.bocasdivecenter.com), which all run trips to outer islands and can arrange all-inclusive packages with accommodations.

Isla Colón isn’t much of a beach destination, although the golden sand of Bluff Beach, 8km (5 miles) by bicycle or taxi from Bocas Town, is worth the effort if short on time. A better alternative is to go on a tour to Bocas del Drago beach on the far north side of the island, where there’s good snorkeling. The tours also usually stop at Swan’s Cay, a bird sanctuary, and Starfish Beach, with lots of tropical fish and a seabed full of starfish. The other option is to take a boat to nearby Isla Bastimentos.

Additionally, there are several large resorts on remote parts of Isla Colón, such as the air-conditioned Playa Tortuga (www.hotelplayatortuga.com) at Playa Big Creek and the rustic bungalows set directly over turquoise waters at Punta Caracol Acqua Lodge (www.puntacaracol.com.pa).

Kuna Yala women.

Robert Harding

Isla Bastimentos

The second largest island in the Bocas del Toro archipelago, Isla Bastimentos is dominated by the Isla Bastimentos National Marine Park, which includes jungle-backed beaches with powdery white sand and the pristine coral formations just off-shore. Bastimentos is much more relaxed than Bocas Town, with just one small creole town of 200 called Old Bank on the western corner of the island, a 15-minute boat ride from Isla Colón. There are a few basic hostels in town, though many come to stay at more isolated resorts like the Red Frog Beach Club (www.redfrogbeach.com) or Tranquilo Bay (www.tranquilobay.com). The nearest beach to Old Bank is Wizard Beach, a short walk away and a beginner surf spot, though Red Frog Beach is much better and can easily be reached on a day trip from Bocas Town. The only other communities on Bastimentos are at Bahía Honda and Salt Creek Village, home to Ngäbe people and one nice resort, La Loma Jungle Lodge (www.thejunglelodge.com), which has its own cacao farm.

The national park extends 12,950 hectares (32,000 acres), most of which cover the reefs, which are notable for their wealth of coral species, fish, and marine invertebrates that range from healthy populations of Elkhorn coral to spotted eagle rays. Leatherback turtles and hawksbill turtles, among others, nest on the 5.6km-long (3.5 miles) Playa Larga on the northern shore. The Zapatilla Cays, named for their resemblance to footprints, are uninhabited inlets with turquoise waters and swaying palms, widely regarded as the best beaches in Bocas.

An islet in the Comarca Kuna Yala.

Shutterstock

Other islands

Off the southern end of Isla Bastimentos is Crawl Cay, about 30 minutes by boat from Bocas Town. The shallow water surrounding the cay is home to soft and hard coral that make it a favorite of divers and snorkelers. Additionally, there are two simple restaurants on the cay, making it a popular day trip.

South of Isla Colón is Isla Cristóbal, one of the larger islands in the archipelago. While the island itself is of little interest, an enclosed bay, Laguna Bocatorito, is a breeding site for bottlenose dolphins. They are best seen from June to September, when they often swim right up to the boats.

The semi-autonomous indigenous province of the Kuna Yala, sometimes referred to as the San Blas archipelago, is a paradisiacal place consisting of 350 of the Caribbean’s most spectacular small islands and cays. Many of the islands are just a strip of powdery white sand backed by a few palm trees and ringed with untouched coral reefs. This is the home of the Kuna who have maintained their cultural identity and control all aspects of tourism to the islands.

Despite the spectacular setting, the Kuna have not allowed mass tourism to permeate the islands. There are no five-star lodges here, just rustic bungalows that lack modern amenities. Even getting hold of them is difficult. Still, with the ability to take quick flights from Panama City to several islands or drive in a short amount of time into the Comarca on the El Llano–Cartí road and take a boat, the effort to reach the region is not nearly as difficult as it once was.

Isla El Porvenir and the west

El Porvenir is the base for the western half of the Comarca Kuna Yala ⁄ [map]. The most regular flights to the region from Panama City land on the tiny airstrip here. There’s a small museum and government offices, although little else other than the experience of immersing yourself in Kuna life. Hotel El Porvenir (www.hotelporvenir.com) offers rooms just beside the airstrip, though there are better, more expensive accommodations on nearby islands, such as Cabañas Narasgandup (www.sanblaskunayala.com). Many travelers catch a boat elsewhere as soon as they land or simply take day trips.

Tiny Isla Hierba has the closest good beach to El Porvenir, while for snorkeling, Isla Perro – with a sunken boat off shore – is better. Not much farther out you come to Isla Pelicano, which has a white sandy beach. Many of the lodges near El Porvenir will include transportation to these islands in their rates.

The stunning chain of cays called the Cayos Holandéses has the best marine life in the area, although they’re 20km (13 miles) away. They have few amenities and the 1.5-hour boat ride each way can be expensive for solo travelers.

The Kuna Yala

Spread out across 49 communities in the Comarca, there are an estimated 50,000 Kuna people, also known as Guna, living in much in the same way they have for centuries. During the time of conquest, many were living in what is today known as the Darién, but fighting with the Catio people and Spanish forced them to the islands. Within the Comarca, each community has its own political organization, led by a political and spiritual leader called a saila, who sings the legends and laws of the Kuna people. He is accompanied by one or two voceros, who help interpret the songs. Kuna families are traditionally matrilineal, as the groom becomes a part of the bride’s family and takes her last name.

In Panama City, the Kuna, who speak a Chibchan language, stand out as they wander through Casco Viejo, wearing their brightly colored headscarves, gold septum rings, and arms and legs covered with beaded bracelets. The Kuna are most famous for their colorful molas, a textile art form made of appliqué and reverse appliqué techniques, which are worn daily by most Kuna women. Trade of the molas, along with that of lobster and coconuts, has allowed the Kuna to function independently while other indigenous groups in Panama have had much difficulty in maintaining their culture.

The Eastern Comarca

Less visited than the west, the eastern half of the Comarca Kuna Yala is more remote and has been more westernized. Air Panama flights from Panama City go to Achutupu, Corazón de Jesús, and Playón Chico, but only sporadically, and without a yacht there’s little other way of getting there. Some of the better accommodations in the region can be found here, however, such as Yandup Island Lodge (www.yandupisland.com). Still, the marine life in this region is quite good, with some of the highest concentrations of coral in Panama.

Dawn at Cerro Pirre peak in Darién National Park.

Alamy

On its journey between Alaska and southern Chile, the Pan-American highway makes one break, which is in Panama’s Darién Province, bordering Colombia. The Darién Gap, as it is called, is composed of nearly a million hectares (2.4 million acres) of virgin rainforest which teems with diverse flora and fauna, all within the boundaries of the Darién National Park, Panama’s largest protected area and a Unesco Biosphere Reserve. While much of the interior is rugged and difficult to reach, the coastlines offer some opportunities to travelers.

Western Darién

Before the Pan-American Highway ends near the town of Metetí, the owners of the more established birding lodges (Canopy Tower and Canopy Lodge) operate Canopy Camp Darien (www.canopytower.com/canopy-camp). This upscale, all-inclusive tent camp borders the edge of the 26,000-hectare (65,000-acre) Serrania Filo del Tallo Hydrological Reserve, which offers opportunities to see harpy eagles and other rare species of birds and mammals.

Darién National Park

Central America’s largest of its kind, Darién National Park ¤ [map] is a Unesco World Biosphere Reserve, covers 575,000 hectares (1.4 million acres). Rarely visited, it is rich with biodiversity, ranging from coastal lagoons to untouched rainforest where jaguars and ocelots have been allowed to flourish. It’s one of the top ten birdwatching destinations on earth, where rare species like red-throated caracaras and golden-headed quetzals are seen with ease.

Without a guide, the park is inaccessible. Apart from Ancon Expeditions (www.anconexpeditions.com), few guides are equipped to handle trips to either of the access points at Cerro Pirre peak on the north side of the park, or the Cana Field Station toward the southeast. Amenities are non-existent other than simple bunks at the ranger stations. From either entrance point, trails lead deep into the interior of the park and some rivers can be traversed by dugout canoe.

The South Coast

Most who come to Piñas Bay do so for one reason: sport fishing. Within 20km (12 miles) of the shore, hundreds of fishing records have been broken, a fame that attracts an elite clientele. They stay at the surprisingly simple Tropic Star Lodge (www.tropicstar.com), which was founded as a private fishing retreat for a Texas oil tycoon. Billfish like black marlin and sailfish are caught from a fleet of 9.4-meter (31ft) Bertram boats that ply the waters off Zane Grey reef.