Leadership Ability Determines

a Person’s Level of Effectiveness

I often open my leadership conferences by explaining the Law of the Lid because it helps people understand the value of leadership. If you can get a handle on this law, you will see the incredible impact of leadership on every aspect of life. So here it is: leadership ability is the lid that determines a person’s level of effectiveness. The lower an individual’s ability to lead, the lower the lid on his potential. The higher the individual’s ability to lead, the higher the lid on his potential. To give you an example, if your leadership rates an 8, then your effectiveness can never be greater than a 7. If your leadership is only a 4, then your effectiveness will be no higher than a 3. Your leadership ability—for better or for worse—always determines your effectiveness and the potential impact of your organization.

Let me tell you a story that illustrates the Law of the Lid. In 1930, two young brothers named Dick and Maurice moved from New Hampshire to California in search of the American Dream. They had just gotten out of high school, and they saw few opportunities back home. So they headed straight for Hollywood where they eventually found jobs on a movie studio set.

After a while, their entrepreneurial spirit and interest in the entertainment industry prompted them to open a theater in Glendale, a town about five miles northeast of Hollywood. But despite all their efforts, the brothers just couldn’t make the business profitable. In the four years they ran the theater, they weren’t able to consistently generate enough money to pay the one hundred dollars a month rent that their landlord required.

A NEW OPPORTUNITY

The brothers’ desire for success was strong, so they kept looking for better business opportunities. In 1937, they finally struck on something that worked. They opened a small drive-in restaurant in Pasadena, located just east of Glendale. People in Southern California had become very dependent on their cars, and the culture was changing to accommodate that, including its businesses.

The drive-in restaurant was a phenomenon that sprang up in the early thirties, and it was becoming very popular. Rather than being invited into a dining room to eat, customers would drive into a parking lot around a small restaurant, place their orders with carhops, and receive their food on trays right in their cars. The food was served on china plates complete with glassware and metal utensils. It was a timely idea in a society that was becoming faster paced and increasingly mobile.

Dick and Maurice’s tiny drive-in restaurant was a great success, and in 1940, they decided to move the operation to San Bernardino, a working-class boomtown fifty miles east of Los Angeles. They built a larger facility and expanded their menu from hot dogs, fries, and shakes to include barbecued beef and pork sandwiches, hamburgers, and other items. Their business exploded. Annual sales reached $200,000, and the brothers found themselves splitting $50,000 in profits every year—a sum that put them in the town’s financial elite.

In 1948, their intuition told them that times were changing, and they made modifications to their restaurant business. They eliminated the carhops and started serving only walk-up customers. And they also stream-lined everything. They reduced their menu and focused on selling ham-burgers. They eliminated plates, glassware, and metal utensils, switching to paper and plastic products instead. They reduced their costs and lowered the prices they charged customers. They also created what they called the Speedy Service System. Their kitchen became like an assembly line, where each employee focused on service with speed. The brothers’ goal was to fill each customer’s order in thirty seconds or less. And they succeeded. By the mid-1950s, annual revenue hit $350,000, and by then, Dick and Maurice split net profits of about $100,000 each year.

Who were these brothers? Back in those days, you could have found out by driving to their small restaurant on the corner of Fourteenth and E Streets in San Bernardino. On the front of the small octagonal building hung a neon sign that said simply McDonald’s Hamburgers. Dick and Maurice McDonald had hit the great American jackpot, and the rest, as they say, is history, right? Wrong. The McDonalds never went any further because their weak leadership put a lid on their ability to succeed.

THE STORY BEHIND THE STORY

It’s true that the McDonald brothers were financially secure. Theirs was one of the most profitable restaurant enterprises in the country, and they felt that they had a hard time spending all the money they made. Their genius was in customer service and kitchen organization. That talent led to the creation of a new system of food and beverage service. In fact, their talent was so widely known in food service circles that people started writing them and visiting from all over the country to learn more about their methods. At one point, they received as many as three hundred calls and letters every month.

That led them to the idea of marketing the McDonald’s concept. The idea of franchising restaurants wasn’t new. It had been around for several decades. To the McDonald brothers, it looked like a way to make money without having to open another restaurant themselves. In 1952, they got started, but their effort was a dismal failure. The reason was simple. They lacked the leadership necessary to make a larger enterprise effective. Dick and Maurice were good single-restaurant owners. They understood how to run a business, make their systems efficient, cut costs, and increase profits. They were efficient managers. But they were not leaders. Their thinking patterns clamped a lid down on what they could do and become. At the height of their success, Dick and Maurice found themselves smack-dab against the Law of the Lid.

THE BROTHERS PARTNER WITH A LEADER

In 1954, the brothers hooked up with a man named Ray Kroc, who was a leader. Kroc had been running a small company he founded, which sold machines for making milk shakes. He knew about McDonald’s. The restaurant was one of his best customers. And as soon as he visited the store, he had a vision for its potential. In his mind he could see the restaurant going nationwide in hundreds of markets. He soon struck a deal with Dick and Maurice, and in 1955, he formed McDonald’s Systems, Inc. (later called the McDonald’s Corporation).

Kroc immediately bought the rights to a franchise so that he could use it as a model and prototype. He would use it to sell other franchises. Then he began to assemble a team and build an organization to make McDonald’s a nationwide entity. He recruited and hired the sharpest people he could find, and as his team grew in size and ability, his people developed additional recruits with leadership skill.

In the early years, Kroc sacrificed a lot. Though he was in his mid-fifties, he worked long hours just as he had when he first got started in business thirty years earlier. He eliminated many frills at home, including his country club membership, which he later said added ten strokes to his golf game. During his first eight years with McDonald’s, he took no salary. Not only that, but he personally borrowed money from the bank and against his life insurance to help cover the salaries of a few key leaders he wanted on the team. His sacrifice and his leadership paid off. In 1961, for the sum of $2.7 million, Kroc bought the exclusive rights to McDonald’s from the brothers, and he proceeded to turn it into an American institution and global entity. The “lid” in the life and leadership of Ray Kroc was obviously much higher than that of his predecessors.

In the years that Dick and Maurice McDonald had attempted to franchise their food service system, they managed to sell the concept to just fifteen buyers, only ten of whom actually opened restaurants. And even in that size enterprise, their limited leadership and vision were hindrances. For example, when their first franchisee, Neil Fox of Phoenix, told the brothers that he wanted to call his restaurant McDonald’s, Dick’s response was, “What . . . for? McDonald’s means nothing in Phoenix.”

In contrast, the leadership lid in Ray Kroc’s life was sky high. Between 1955 and 1959, Kroc succeeded in opening 100 restaurants. Four years after that, there were 500 McDonald’s. Today the company has opened more than 31,000 restaurants in 119 countries.1 Leadership ability—or more specifically the lack of leadership ability—was the lid on the McDonald brothers’ effectiveness.

SUCCESS WITHOUT LEADERSHIP

I believe that success is within the reach of just about everyone. But I also believe that personal success without leadership ability brings only limited effectiveness. Without leadership ability, a person’s impact is only a fraction of what it could be with good leadership. The higher you want to climb, the more you need leadership. The greater the impact you want to make, the greater your influence needs to be. Whatever you will accomplish is restricted by your ability to lead others.

The higher you want to climb, the more you need leadership. The greater the impact you want to make, the greater your influence needs to be.

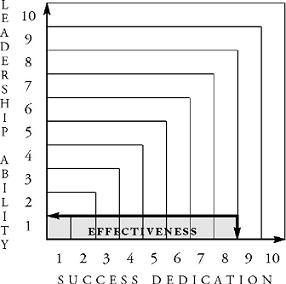

Let me give you a picture of what I mean. Let’s say that when it comes to success, you’re an 8 (on a scale from 1 to 10). That’s pretty good. I think it would be safe to say that the McDonald brothers were in that range. But let’s also say that leadership isn’t even on your radar. You don’t care about it, and you make no effort to develop as a leader. You’re functioning as a 1. Your level of effectiveness would look like this:

SUCCESS WITHOUT LEADERSHIP

To increase your level of effectiveness, you have a couple of choices. You could work very hard to increase your dedication to success and excellence—to work toward becoming a 10. It’s possible that you could make it to that level, though the Law of Diminishing Returns says that the effort it would take to increase those last two points might take more energy than it did to achieve the first eight. If you really killed yourself, you might increase your success by that 25 percent.

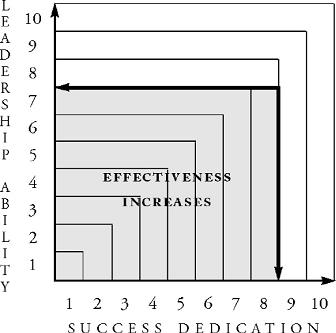

But you have another option. You can work hard to increase your level of leadership. Let’s say that your natural leadership ability is a 4—slightly below average. Just by using whatever God-given talent you have, you already increase your effectiveness by 300 percent. But let’s say you become a real student of leadership and you maximize your potential. You take it all the way up to a 7. Visually, the results would look like this:

SUCCESS WITH LEADERSHIP

By raising your leadership ability—without increasing your success dedication at all—you can increase your original effectiveness by 600 per-cent. Leadership has a multiplying effect. I’ve seen its impact again and again in all kinds of businesses and nonprofit organizations. And that’s why I’ve taught leadership for more than thirty years.

TO CHANGE THE DIRECTION OF THE

ORGANIZATION, CHANGE THE LEADER

Leadership ability is always the lid on personal and organizational effectiveness. If a person’s leadership is strong, the organization’s lid is high. But if it’s not, then the organization is limited. That’s why in times of trouble, organizations naturally look for new leadership. When the country is experiencing hard times, it elects a new president. When a company is losing money, it hires a new CEO. When a church is floundering, it searches for a new senior pastor. When a sports team keeps losing, it looks for a new head coach.

The relationship between leadership and effectiveness is perhaps most evident in sports where results are immediate and obvious. Within professional sports organizations, the talent on the team is rarely the issue. Just about every team has highly talented players. Leadership is the issue. It starts with a team’s owner and continues with the coaches and some key players. When talented teams don’t win, examine the leadership.

Personal and organizational effectiveness is proportionate to the strength of leadership.

Wherever you look, you can find smart, talented, successful people who are able to go only so far because of the limitations of their leadership. For example, when Apple got started in the late 1970s, Steve Wozniak was the brains behind the Apple computer. His leadership lid was low, but that was not the case for his partner, Steve Jobs. His lid was so high that he built a world-class organization and gave it a nine-digit value. That’s the impact of the Law of the Lid.

In the 1980s, I met Don Stephenson, the chairman of Global Hospitality Resources, Inc., of San Diego, California, an international hospitality advisory and consulting firm. Over lunch, I asked him about his organization. Today he primarily does consulting, but back then his company took over the management of hotels and resorts that weren’t doing well financially. His company oversaw many excellent facilities, such as La Costa in Southern California.

Don said that whenever his people went into an organization to take it over, they always started by doing two things. First, they trained all the staff to improve their level of service to the customers, and second, they fired the leader. When he told me that, I was surprised.

“You always fire him?” I asked. “Every time?”

“That’s right. Every time,” he said.

“Don’t you talk to the person first—to check him out to see if he’s a good leader?” I said.

“No,” he answered. “If he’d been a good leader, the organization wouldn’t be in the mess it’s in.”

And I thought to myself, Of course. It’s the Law of the Lid. To reach the highest level of effectiveness, you have to raise the lid—one way or another.

The good news is that getting rid of the leader isn’t the only way. Just as I teach in conferences that there is a lid, I also teach that you can raise it—but that’s the subject of another law of leadership.

Applying

THE LAW OF THE LID

To Your Life

1. List some of your major goals. (Try to focus on significant objectives—things that will require a year or longer of your time. List at least five but no more than ten items.) Now identify which ones will require the participation or cooperation of other people. For these activities, your Leadership ability will greatly impact your effectiveness.

2. Assess your leadership ability. Complete the leadership evaluation in Appendix A at the back of this book to get an idea of your basic leadership ability.

3. Ask others to rate your leadership. Talk to your boss, your spouse, two colleagues (at your level), and three people you lead about your leadership ability. Ask each of them to rate you on a scale of 1 (low) to 10 (high) in each of the following areas:

People skills

People skills

Planning and strategic thinking

Planning and strategic thinking

Vision

Vision

Results

Results

Average the scores, and compare them to your own assessment. Based on these assessments, is your leadership skill better or worse than you expected? If there is a gap between your assessment and that of others, what do you think is the cause? How willing are you to grow in the area of leadership?